Abstract

During natural infection by HIV-1, antibodies are generated against the region of the viral gp120 envelope glycoprotein that binds CD4, the primary receptor for HIV-1. Among these antibodies, VRC01 achieves extensive neutralization of diverse viral strains. To understand the structural basis for its neutralization breadth and potency, we determined the crystal structure of VRC01 in complex with an HIV-1 gp120 core. The heavy chain of VRC01 interacts with gp120 in a manner similar to CD4. A 43° rotation coupled with a 6-Å shift from the CD4-defined orientation focuses VRC01 onto the conformationally invariant site of initial CD4 attachment, allowing it to overcome the masking that diminishes the neutralization potency of most CD4-binding-site antibodies. To achieve this mode of recognition, VRC01 contacts gp120 mainly through V-gene-derived regions substantially altered from their genomic precursors. Partial receptor mimicry and extensive affinity maturation thus facilitate effective neutralization of HIV-1 by natural human antibodies.

Successful vaccine development often utilizes clues from humoral responses elicited by natural infection. For HIV-1, neutralizing antibody responses elicited within the first year or two of infection are generally strain-specific (1), and emulation of these responses in uninfected individuals is unlikely to prevent infection by diverse viral strains [reviewed in (2)]. Because a select few monoclonal antibodies from HIV-1 infected individuals can effectively neutralize many HIV-1 strains, an effort has been made to facilitate vaccine design by defining the structures of broadly neutralizing antibodies. Atomic-level characterization of their recognized epitopes enables the creation of immunogens that resemble highly conserved viral structures and that elicit immune responses similar to the original antibody (3-4).

The well-studied broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies, 2G12, 2F5, 4E10, and b12, contain unusual characteristics that have posed barriers to eliciting similar antibodies in humans (5). Thus, in addition to having broad capacity for neutralization, an appropriate antibody should be present in high titers in humans as this provides evidence that such antibodies can be elicited in useful concentrations. To identify such antibodies, we and others have screened cohorts of sera from infected individuals not only to find broadly neutralizing responses but also to characterize those detectable in a substantial percentage of subjects (6-10). One antibody response that satisfies these criteria is directed towards the site of CD4 attachment on the HIV-1 gp120 envelope (Env) glycoprotein (8).

While potentially accessible, the CD4-binding site is protected from humoral recognition by glycan and conformational masking (11). To identify monoclonal antibodies against this site, in a companion manuscript, we created resurfaced, conformationally stabilized probes, with antigenic specificity for the initial site of CD4 attachment on gp120, and we used these probes to identify antibodies that neutralize most viruses (12). Here, we analyze the crystal structure for one of these antibodies, VRC01, in complex with an HIV-1 gp120 core from a clade A/E recombinant strain. We decipher the basis of VRC01 neutralization, identify mechanisms of natural resistance, show how VRC01 minimizes such resistance, and define the role of affinity maturation in gp120 recognition. These molecular details should facilitate efforts to guide the maturation of VRC01-like antibodies from genomic rearrangement through affinity maturation to effective neutralization of HIV-1.

Similarities of Env recognition by CD4 and VRC01 antibody

To gain a structural understanding of VRC01 neutralization, we crystallized the antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of VRC01 in complex with an HIV-1 gp120 from the clade A/E recombinant 93TH057 (13). The crystallized gp120 consisted of its inner domain-outer domain core, with truncations in the variable loops V1/V2 and V3 as well as the N- and C-termini, regions which we had previously found to extend away from the main body of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein (14). Diffraction to 2.9 Å resolution was obtained from orthorhombic crystals, which contained four copies of the VRC01-gp120 complex per asymmetric unit, and the structure was solved by molecular replacement and refined to an R-value of 24.4% (Rfree of 25.9%) (Fig. 1 and Table S1) (15).

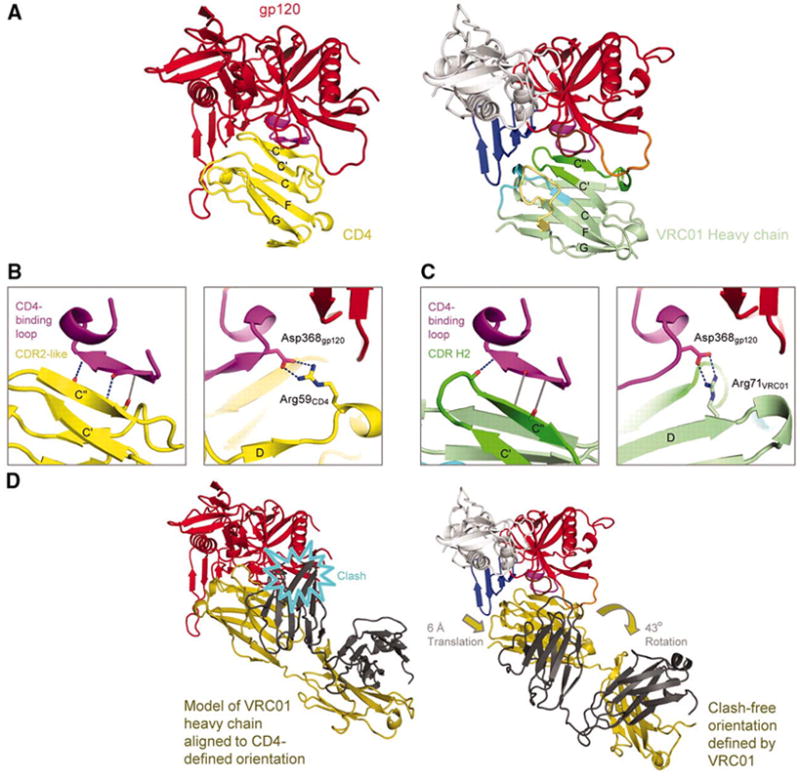

Figure 1. Structure of antibody VRC01 in complex with HIV-1 gp120.

Atomic-level details for effective recognition of HIV-1 by a natural human antibody are depicted with polypeptide chains in ribbon representations. The gp120 inner domain is shown in gray, the bridging sheet in blue, and the outer domain in red, except for the CD4-binding loop (purple), the D loop (brown), and the V5 loop (orange). The light chain of the antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of VRC01 is shown in light blue with complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) highlighted in dark blue (CDR L1) and marine blue (CDR L3). The heavy chain of Fab VRC01 is shown in light green with CDRs highlighted in cyan (CDR H1), green (CDR H2), and pale yellow (CDR H3). Both light and heavy chains of VRC01 interact with gp120: the primary interactive surface is provided by the CDR H2, with the CDR L1 and L3 and the CDR H1 and H3 providing additional contacts.

The interactive surface between VRC01 and gp120 encompasses almost 2500 Å2, 1244 Å2 contributed by VRC01 and 1249 Å2 by gp120 (16). On VRC01, both heavy chain (894 Å2) and light chain (351 Å2) contribute to the contact surface (Table S2), with the central focus of binding on the heavy chain second complementarity-determining region (CDR H2). Over half of the interactive surface of VRC01 (644 Å2) involves CDR H2, a mode of binding reminiscent of the interaction between gp120 and the CD4 receptor; CD4 is a member of the V-domain class of the immunoglobulin superfamily (17), and the CDR2-like region of CD4 is a central focus of gp120 binding (Figs. 2A and Table S3) (18). For CD4, the CDR2-like region forms antiparallel, intermolecular hydrogen-bonds with residues 365-368gp120 of the CD4-binding loop of gp120 (18) (Fig. 2B); with VRC01, one hydrogen-bond is observed between the carbonyl of Gly54VRC01 and the backbone nitrogen of Asp368gp120. This hydrogen-bond occurs at the loop tip, an extra residue relative to CD4 is inserted in the strand, and the rest of the potential hydrogen bonds are of poor geometry or distance (Fig. 2C and Table S4). Other similarities and differences with CD4 are found: of the two dominant CD4 residues (Phe43CD4 and Arg59CD4) involved in interaction with gp120, VRC01 mimics the arginine interaction, but not the phenylalanine one (Fig. 2B, C). Finally, significant correlation is observed between gp120 residues involved in binding VRC01 and CD4 (Fig. S1).

Figure 2. Structural mimicry of CD4 interaction by antibody VRC01.

VRC01 shows how a double-headed antibody can mimic the interactions with HIV-1 gp120 of a single-headed member of the immunoglobulin superfamily such as CD4. (A) Comparison of HIV-1 gp120 binding to CD4 (N-terminal domain) and VRC01 (heavy chain-variable domain). Polypeptide chains are depicted in ribbon representation for the VRC01 complex (right) and the CD4 complex with the lowest gp120 RMSD (left) (Table S3). The CD4 complex (3JWD) (14) is colored yellow for CD4 and red for gp120, except for the CDR-binding loop (purple). The VRC01 complex is colored as in Fig. 1. Immunoglobulin domains are composed of two β-sheets, and the top sheet of both ligands is labeled with the standard immunoglobulin-strand topology (strands G, F, C, C’, C”). (B,C) Interface details for CD4 (B) and VRC01 (C). Close-ups are shown of critical interactions between the CD4-binding loop (purple) and the C” strand as well as between Asp368gp120 and either Arg59CD4 or Arg71VRC01. Hydrogen bonds with good geometry are depicted by blue dotted lines, and those with poor geometry in gray. Atoms from which hydrogen bonds extend are depicted in stick representation and colored blue for nitrogen and red for oxygen. In the left panel of C, the β15-strand of gp120 is depicted to aid comparison with B, though because of the poor hydrogen-bond geometry, it is only a loop. (D) Comparison of VRC01- and CD4-binding orientations. Polypeptides are shown in ribbon representation, with gp120 colored the same as in (A) and VRC01 depicted with heavy chain in dark yellow and light chain in dark gray. When the heavy chain of VRC01 is superimposed onto CD4 in the CD4-gp120 complex, the position assumed by the light chain evinces numerous clashes with gp120 (left). The VRC01-binding orientation (right) avoids clashes by adopting an orientation rotated by 43° and translated by 6-Å.

Superposition of the gp120 core in its VRC01-bound form with gp120s in other crystalline lattices and bound by other ligands indicates a CD4-bound structure (PDB ID 3JWD) (14) to be most closely related in structure, with a Cα-root-mean-square deviation of 1.03 Å (Table S5). Such superposition of gp120s from CD4-bound and VRC01-bound conformations brings the N-terminal domain of CD4 and the heavy chain variable domain of VRC01 into close alignment (Fig. 2), with 73% of the CD4 N-terminal domain volume overlapping with VRC01 (19). This domain overlap is much higher than observed with the heavy chains of other CD4-binding site antibodies, such as b12, b13 or F105 (Table S6). However, when the VRC01 heavy chain is superimposed - based on conserved framework and cysteine residues - on CD4 in the CD4-gp120 complex, clashes are found between gp120 and the entire top third of the VRC01 variable light chain (Fig. 2D) (20). In its complex with gp120, VRC01 rotates 43° relative to the CD4-defined orientation, and translates 6-Å away from the bridging sheet, to a clash-free orientation that mimics many of the interactions of CD4 with gp120, though with considerable variation. Analysis of electrostatics shows that the interactive surfaces of VRC01 and CD4 are both quite basic, though the residues types of contacting amino acids are distinct (Fig. S2). Thus, while VRC01 mimics CD4 binding to some extent, considerable differences are observed.

Structural basis of VRC01 breadth and potency

When CD4 is placed into an immunoglobulin context by fusing its two N-terminal domains to the dimeric immunoglobulin constant region, it achieves reasonable neutralization. VRC01, however, neutralizes better (Fig. 3A) (12). To understand the structural basis for the exceptional breadth and potency of VRC01, we analyzed its interactive surface with gp120. VRC01 focuses its binding onto the conformationally invariant outer domain, which accounts for 87% of the contact-surface area of VRC01 (Fig. 3B, Table S7). The 13% of the contacts made with flexible inner domain and bridging sheet are non-contiguous and are not critical for binding. In contrast, CD4 makes 33% of its contacts with the bridging sheet, and many of these interactions are essential (18). The reduction in inner domain and bridging sheet interactions by VRC01 is accomplished primarily by a 6-Å translation relative to CD4 away from these regions; critical contacts such as made by Phe43CD4 to the nexus of the bridging sheet-outer domain are not found in VRC01, while those to the outer domain (e.g. Arg59CD4) are mimicked by VRC01.

Figure 3. Structural basis of antibody VRC01 neutralization breadth and potency.

VRC01 displays remarkable neutralization breadth and potency, a consequence in part of its ability to bind well to different conformations of HIV-1 gp120. (A) Neutralization dendrograms. The genetic diversity of current circulating HIV-1 strains is displayed as a dendrogram, with locations of prominent clades (e.g. A, B and C) and recombinants (e.g. CDR02_AG) labeled. The strains are colored by their neutralization sensitivity to VRC01 (left) or CD4 (right). VRC01 neutralizes 72% of the tested HIV-1 isolates with an IC80 of less than 1 ug/ml; by contrast, CD4 neutralizes 30% of the tested HIV-1 isolates with an IC80 of less than 1 ug/ml (Table S13). (B) Molecular footprints of VRC01 and CD4 on gp120. The molecular surface of HIV-1 gp120 has been colored according to its underlying domain substructure: red for the conformationally invariant outer domain, grey for the inner domain and blue for the highly mobile bridging sheet. Regions of the gp120 surface that interact with VRC01 or CD4 have been colored in green and yellow respectively. (C) Neutralization of viruses with altered sampling of the CD4-bound state. Mutant S375Wgp120 favors the CD4-bound state, whereas mutants H66Agp120 and W69Lgp120 disfavor this state. Neutralization by VRC01 (left) is similar for wild-type (WT) and all three mutant viruses, whereas neutralization by CD4 (right) correlates with the degree to which gp120 in the mutant viruses favors the CD4-bound state. (D) Comparison of binding affinities. Binding affinities (KDs) for VRC01 and various other gp120-reactive ligands as determined by surface-plasmon resonance are shown on a bar graph. White bars represent affinities for gp120 restrained from assuming the CD4-bound state (21) and black bars represent affinities for gp120 fixed in the CD4-bound state (24). Binding too weak to be measured accurately is shown as with an asterisk and bar at 10-5 M KD.

To determine the affinity of VRC01 for gp120 in CD4-bound and non-CD4-bound conformations, we used surface-plasmon resonance spectroscopy to measure the affinity of VRC01 and other gp120-reactive antibodies and ligands to two gp120s: a β4-deletion developed by Harrison and colleagues that is restrained from assuming the CD4-bound conformation (21) or a disulfide-stabilized gp120 core, largely fixed in the CD4-bound conformation in the absence of CD4 itself (18) (Fig. 3D) (Fig. S3). VRC01 showed high affinity to both CD4-bound and non-CD4-bound conformations, a property shared by the broadly neutralizing b12 antibody (21-22). By contrast, antibodies F105 and 17b as well as soluble CD4 showed strong preference for only one, but not both, of the conformations. Thus, VRC01 interacts with the conformationally invariant outer domain in a manner that enables recognition of both CD4-bound and non-CD4-bound conformations of gp120.

To assess the binding of VRC01 in the context of the functional viral spike, we examined its ability to neutralize variants of HIV-1 with gp120 changes that affect the CD4-bound state. Two of these mutations, His66Ala gp120 and Trp69Leugp120, reduce the ability of virus to sample the CD4-bound state and are less sensitive to neutralization by CD4 (23). One of the mutations, Ser375Trp gp120, increases formation of the CD4-bound state and is more sensitive to neutralization by CD4 (23-24). VRC01 neutralized all three of these variant HIV-1 viruses with similar potency (Fig. 3C), suggesting that VRC01 recognizes both CD4-bound and non-CD4-bound conformations of the viral spike. This recognition diversity allows VRC01 to avoid the conformational masking that hinders most CD4-binding-site ligands (25) and to neutralize HIV-1 potently.

Precise targeting by VRC01

Prior analysis of effective and ineffective CD4-binding-site antibodies suggested that precise targeting to the initial site of CD4 attachment is required to block viral entry (11, 26). The initial site of CD4 attachment is a subset of the CD4-binding site that involves the conformationally invariant outer domain (22). Analysis of the VRC01 interaction with gp120 shows that it covers 98% of the target site (Figs. 4A and S4), comprising 1089 Å2 on the gp120 outer domain, about 50% larger than the 730 Å2 surface utilized by CD4. The VRC01 contact surface outside the target site is largely limited to the conformationally invariant outer domain and avoids regions of conformational flexibility. This concordance of binding is much greater than for ineffective CD4-binding-site antibodies, as well as for those that are partially effective, such as antibody b12 (11, 22) (Fig. S4).

Figure 4. Natural resistance to antibody VRC01.

VRC01 precisely targets the CD4-defined site of vulnerability on HIV-1 gp120. Its binding surface, however, extends outside of the target site, and this allows for natural resistance to VRC01 neutralization. (A) VRC01 recognition and target site of vulnerability. The CD4-define site of vulnerability is the initial contact surface of the outer domain of gp120 for CD4 and comprises only 2/3 of the contact surface of gp120 for CD4 (22). The molecular surface of gp120 in the VRC01 bound conformation is colored according to its domain substructure as in Fig. 3B, with the interactive footprint of VRC01 shown in green and the CD4-defined site of vulnerability outlined in yellow. (B) Antigenic variation. The polypeptide backbone of gp120 is colored according to sequence conservation, blue if conservation is high and red if conservation is low. (C) VRC01-resistant HIV-1 isolates. The 17 isolates of HIV-1 that resist VRC01 neutralization are displayed in ribbon and stick representation after threading onto the structure of gp120 in the VRC01-bound conformation. Side chains that clashed with VRC01 are highlighted in red. (D) Sequence in V5 region for 17 HIV-1 isolates that resist neutralization by VRC01. (E) HIV-1 clashes with VRC01. A close-up of threaded, resistant isolates is shown along with the molecular surface of VRC01, colored light blue for the light chain and green for the heavy chain. Clashes predicted to interfere with VRC01-gp120 interactions are highlighted in red. (F) Molecular surface of VRC01 and select interactive loops of gp120. Variation at the tip of the V5 loop is accommodated by a gap between heavy and light chains of VRC01.

Contacts by the VRC01 light chain (Tyr28VRC01 and Ser30VRC01) are made with the protein-proximal N-acetyl-glucosamine from the N-linked glycan at residue 276gp120 (27). Thus, instead of being occluded by glycan shielding, VRC01 makes use of a glycan for binding. Other potential glycan interactions may occur with different strains of HIV-1 gp120, as the VRC01 recognition surface on the gp120-outer domain extends further than that of the functionally constrained CD4-interactive surface, especially into the loop D and the often-glycosylated V5 region (Fig 4D).

Natural resistance to antibody VRC01

In addition to conformational masking and glycan shielding, HIV-1 resists neutralization by antigenic variation. In a companion manuscript, we show that of the 190 circulating HIV-1 isolates tested for sensitivity to VRC01, 173 were neutralized and 17 were resistant (12). To understand the basis of this natural resistance to VRC01, we analyzed all 17 resistant isolates by threading their sequences onto the gp120 structure (Fig. 4C). Variation was observed in the V5 region in resistant isolates, and this variation – along with alterations in gp120 loop D - appeared to be the source of most natural resistance to VRC01 (Figs. 4D, 4E, S5).

Because substantial variation exists in V5, structural differences in this region might be expected to result in greater than 10% resistance. The lower observed frequency of resistance suggests that VRC01 employs a recognition mechanism that allows for binding despite V5 variation. Examination of VRC01 interaction with V5 shows that VRC01 recognition of V5 is considerably different from that of CD4 (Fig. S6), with Arg61VRC01 in the CDR H2 penetrating into the cavity formed by the V5 and β24-strands of gp120 (Fig. S7). Most importantly, the V5 loop fits into the gap between heavy and light chains; thus by contacting only the more conserved residues at the loop base, VRC01 can tolerate variation in the tip of the V5 loop (Fig. 4F).

Unusual VRC01 features and contribution to recognition

We examined the structure of VRC01 for special features that might be required for its efficacy. A number of unusual features were apparent, including a high degree of affinity maturation, an extra disulfide bond, a site for N-linked glycosylation, a 2-amino acid deletion in the light chain, and a significantly matured binding interface between VRC01 and gp120 (Fig. 5). We assessed the frequency with which these features were found in HIV-1 Env-reactive antibodies (SOM Appendix) or in human antibody-antigen complexes (Fig. S9), and measured the effect of genomic reversion on affinity for gp120 (Fig. 5B-E).

Figure 5. Unusual VRC01 features.

The structure of VRC01 displays a number of unusual features, which if essential for recognition and difficult to elicit, might inhibit the elicitation of VRC01-like antibodies. (A) VRC01 sequence and extent of affinity maturation. The sequence of VRC01 is shown along with nearest VH- and VΚ/λ-genomic precursors for heavy and light chain, respectively. Affinity maturation changes are indicated in green, with residues involved in interaction with HIV-1 gp120 highlighted by “●”, if involved in both main- and side-chain interactions, by “○” if main chain-only, and by “☼” if side chain-only. “ ” marks a site of N-linked glycosylation, “

” marks a site of N-linked glycosylation, “ ” for cysteine residues involved in a non-canonical disulfide, and “

” for cysteine residues involved in a non-canonical disulfide, and “ ” if the residue has been deleted during affinity maturation. In B-E, unusual features of VRC01 are shown structurally (far left panel), in terms of frequency as a histogram with other antibodies (second panel from left), and in the context of affinity meaurements after mutational alteration (right two panels). Affinity measurements were made by ELISA to the gp120 construct used in crystallization (93TH057) and to a disulfide stabilized HXBc2 core (22). (B) N-linked glycosylation. The conserved tri-mannose core is shown with observed electron density, along with frequency and effect of removal on affinity. (C) Extra disulfide. Variable heavy domains naturally have two Cys, linked by a disulfide; VRC01 has an extra disulfide linking CDR H1 and H3 regions. This occurs rarely in antibodies, but its removal by mutation to Ser/Ala has little effect on affinity. (D) CDR L1 deletion. A two amino acid deletion in the CDR L1, prevents potential clashes with loop D of gp120. Such deletions are rarely observed; reversion to the longer loop may have a 10-100-fold effect on gp120 affinity. (E) Somatically altered contact surface. The far left panel shows the VRC01 light chain in violet and heavy chain in green. Residues altered by affinity maturation are depicted with “balls” and contacts with HIV-1 gp120 are colored red. About half the contacts are altered during the maturation process. Analysis of human antibody-protein complexes in the protein-data bank shows this degree of contact surface alteration is rare; reversion of each of the contact site to genome has little effect (Table S12), though in aggregate the effect on affinity is larger.

” if the residue has been deleted during affinity maturation. In B-E, unusual features of VRC01 are shown structurally (far left panel), in terms of frequency as a histogram with other antibodies (second panel from left), and in the context of affinity meaurements after mutational alteration (right two panels). Affinity measurements were made by ELISA to the gp120 construct used in crystallization (93TH057) and to a disulfide stabilized HXBc2 core (22). (B) N-linked glycosylation. The conserved tri-mannose core is shown with observed electron density, along with frequency and effect of removal on affinity. (C) Extra disulfide. Variable heavy domains naturally have two Cys, linked by a disulfide; VRC01 has an extra disulfide linking CDR H1 and H3 regions. This occurs rarely in antibodies, but its removal by mutation to Ser/Ala has little effect on affinity. (D) CDR L1 deletion. A two amino acid deletion in the CDR L1, prevents potential clashes with loop D of gp120. Such deletions are rarely observed; reversion to the longer loop may have a 10-100-fold effect on gp120 affinity. (E) Somatically altered contact surface. The far left panel shows the VRC01 light chain in violet and heavy chain in green. Residues altered by affinity maturation are depicted with “balls” and contacts with HIV-1 gp120 are colored red. About half the contacts are altered during the maturation process. Analysis of human antibody-protein complexes in the protein-data bank shows this degree of contact surface alteration is rare; reversion of each of the contact site to genome has little effect (Table S12), though in aggregate the effect on affinity is larger.

Higher levels of affinity maturation have been reported for HIV-1 reactive antibodies in general (28), and markedly higher levels for broadly neutralizing ones (29). But these levels could be the result of the persistent nature of HIV-1 infection, and not an intrinsic limitation on the elicitation. Each of the other special features was observed in less than 5% of HIV-1 Env-reactive antibodies or was more than 4-standard deviations away from average (Fig. S9 and Tables S10, S11). Removal of the N-linked glycosylation or the extra disulfide bond, which connects CDR H1 and H3 regions of the heavy chain, had little effect on binding (Figs. 5B, 5C and Table S12). Insertion of 2-amino acids to revert the light chain deletion had a moderate effect, which was larger for an Ala-Ala insertion (50-fold decrease in KD) versus a Ser-Tyr insertion (5-fold decrease in KD), which mimics the genomic sequence (Fig. 5D). Finally reversion of the interface was examined with either single-, 4-, 7- or 12-mutant reversions. For the single-mutant reversions of the interface, all 12 mutations had minor effects (most with less than 2-fold effect on KD, with the largest effect for a Gly54Ser change with a KD of 20.2 nM) (Table S12). Larger effects were observed with multiple (4, 7 or 12) changes, and these reduced the measured KD by 5-30-fold and EC50s by 10-100-fold, depending on the amino-acid changes and the gp120 to which binding was tested (Fig. 5E and Table S12). Thus, while VRC01 had a number of unusual features, no single alteration to genomic sequence reduced affinity by more than 10-fold. The largest effect involved a light chain deletion. This same deletion is seen in antibody VRC03, a variant of VRC01, which we isolated from the same patient and has the same heavy chain, but different light chain, a product of receptor editing (12, 30). The presence of this deletion in the light chains of both VRC01 and VRC03 illustrates its importance to the VRC01-mode of HIV-1 recognition, and also demonstrates that acquiring this feature is not unique to VRC01.

Elicitation of VRC01-like antibodies

The probability of elicitation for a particular antibody is a function of each of the three major steps in B cell maturation: 1. Recombination to produce nascent antibody heavy and light chains from genomic VH-D-J and Vκ/λ-J precursors; 2. Deletion of auto-reactive antibodies; and 3. Maturation through hypermutation of the variable domains to enhance antigen affinity. In terms of the first step, recombination, it is possible to infer from the VRC01-gp120 structure what portions of the antibody precursor genes are critical for Env recognition and what recombination events are essential, thereby providing insight into the frequency of genomic rearrangements appropriate for generating VRC01-like antibodies. In the VRC01-gp120 structure, a lack of substantial CDR L3 and H3 contribution indicates that specific Vκ/λ -J or VH(D)J- recombination is not required (31). The majority of recognition occurs with elements encoded in single genomic elements or cassettes, suggesting that specific joints between defined cassettes are not required. Within the VH cassette, a number of residues associated with the IGHV1-02*02 precursor of VRC01 interact with gp120; many of these are conserved in related genomic VHs, some of which are of similar genetic distance from VRC01 (Fig. S8). Together, these results suggest only modest constraints on recombination to produce VRC01-like antibodies, and that appropriate genomic precursors are likely to occur at reasonable frequency in the human antibody repertoire.

Recombination produces nascent B cell-presented antibodies that have reactivities against both self and nonself antigens. Those with auto-reactivity are removed through clonal deletion. With many of the broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies, such as 2G12 (glycan reactive) (32-33), 2F5 and 4E10 (membrane reactive) (34-35), this appears to be a major barrier to elicitation. While this remains to be characterized for genomic revertants and intermediates, no auto-reactivity has so far been observed with VRC01 (12), suggesting that this step does not provide a limitation on elicitation of VRC01-like antibodies.

Affinity maturation and VRC01-like antibodies

The third step influencing the elicitation of VRC01-like antibodies is affinity maturation, the process by which hypermutation of variable domains combined with affinity-based selection occurs during B cell maturation in germinal centers (36). This process allows for the rapid evolution of antibodies from low (uM) to moderate affinity for antigen in the initial rearrangement to tight (nM) affinity for a fully matured antibody. Some variable domain alterations are difficult to detect, as recombination produces unpredictable amino acids at the junctions between V, D and J segments. Changes from the precursor within the V- and J-genes, however, can be known with greater certainty. In the case of VRC01, 41 residue alterations were observed from the genomic VH-gene and 25 alterations from the VΚ-gene (including a deletion of two residues) (Fig. 5A). As noted previously (12), these levels of affinity maturation changes are unusual, even for HIV-1 Env-reactive antibodies (37).

To investigate the effect of affinity maturation on HIV-1 gp120 recognition, we reverted the VH- and VΚ-regions of VRC01, either individually or together, to the sequences of their genomic precursors and tested the affinity of the reverted antibodies for gp120. With 93TH057 gp120, reversion to germline-VH reduced the EC50 ~1000-fold, and no binding was observed with VΚ revertants. With the HXBc2 core gp120 disulfide-stabilized in the CD4-bound state (22), less dramatic reductions in binding were observed, with VΚ reversion reducing binding 10-fold, VH reversion reducing binding 100-fold, and VH-, VΚ-simultaneous reversions eliminating detectable binding (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Somatic maturation and VRC01 affinity.

Hypermutation of the variable domain during B cell maturation allows for the evolution of high affinity antibodies. Interestingly, this enhancement to affinity occurs principally through the alteration of non-contact residues, which appear to reform the genomic contact surface from affinity too low to measure to a tight (nM) interaction. (A) Effect of genomic reversions. The VH- and VΚ-derived regions of VRC01 were reverted to the sequences of their closest genomic precursors, expressed as immunoglobulins and tested for binding as VH- and VΚ-revertants (gHgL), as a VH-only revertant (gH), or as a VΚ-only revertant (gL) to either the gp120 construct used in crystallization (93TH057) or to a stabilized HXBc2 core (22). (B) Maturation of VRC01 and correlation with binding. Affinity measurements for the 19 VRC01 mutants created during the structure-function analysis of VRC were analyzed in the context of their degree of affinity maturation. Significant correlations were observed, with extrapolation to VH- and VΚ-revertants suggesting greatly reduced affinity for gp120. (C) Maturation of VRC01 and effect on HIV-1 gp120 affinity. Cryo-electron microscopy density (pink) corresponding to the unliganded state of the trimeric HIV-1 viral spike (50) is shown in complex with the antigen-binding fragment of VRC01. The Cα-backbone ribbon is displayed for gp120s (red) and VRC01 grey. With VRC01, the molecular surface is shown for residues altered from the closest VH- and VΚ-genomic precursor sequences and colored gray to green depending on the effect of the reversion on gp120 affinity, with gray indicating small effects and green larger ones.

In addition to the whole-scale heavy and light chain revertants, a number of other revertants were produced while analyzing unusual VRC01 characteristics (Table S12). These revertants provide a basis for an analysis of the overall effect of affinity maturation. We correlated the measured EC50s with the number of affinity-matured residues in VH and VΚ regions (Fig. 6B) (38). Binding affinities of revertants for both crystallized gp120 and to an HXBc2 gp120 core stabilized in the CD4-bound conformation showed significant correlations with the number of affinity-matured residues (p<0.0001). Changes were roughly 4-fold greater with the crystallized gp120 than with the stabilized gp120. In both cases, extrapolation of the correlation to the putative genomic V-gene sequences reduced binding to 0.6-4.9 10-6 M KD (Figs. 6B and S12), which is beyond the range of detection of the ELISA, a result confirmed experimentally (Fig. 6A).

Similar significant reductions in affinity have been observed with reversion of other broadly neutralizing, anti-HIV-1 antibodies to presumed genomic sequences (39-40); these observations have led to the suggestion that the dramatically reduced germline affinity for gp120 might hinder the initiation of affinity maturation of these antibodies (41). That is, if the affinity for gp120 of the genomic precursor of a broadly neutralizing antibody were below the threshold required for the nascent B cell to mature, then maturation would either not occur or would need to occur in response to a different immunogen. This lack of guided initiation of the maturation process may provide an explanation for the absence of such broadly neutralizing antibodies in the first few years of infection. Conversely, the introduction of modified gp120s with affinity to genomic precursors and affinity maturation intermediates could provide a mechanism by which to elicit antibodies like VRC01.

Notably, no single affinity maturation alteration appeared to affect affinity by more than 10-fold, suggesting that affinity maturation occurs in multiple small steps, which collectively enable tight binding to HIV-1 gp120. When the effects on viral neutralization of VRC01 affinity maturation reversions are mapped to the structure of the VRC01-gp120 complex (Fig. 6C), these effects are broadly distributed throughout the VRC01 variable domains, not focused on the VRC01-gp120 interface; non-contact residues apparently influence the interface with gp120 through indirect protein-folding effects (Fig. 6C). Thus, for VRC01, the process of affinity maturation entails incremental changes of the nascent genomic precursors to obtain high affinity interaction with HIV-1 Env surface.

Receptor mimicry and affinity maturation

The possibility of antibodies using conserved sites of receptor recognition to neutralize viruses effectively has been pursued for several decades. The recessed canyon on rhinovirus that recognizes the unpaired terminal immunoglobulin domains of ICAM-1 highlights the steric role that a narrow canyon entrance may play in occluding bivalent antibody-combining regions (42), although framework recognition can in some instances permit entry (43). Antigenic variation may still allow for viral escape even with less recessed binding sites, such as observed with the sialic acid-receptor binding site on the hemagglutinin of influenza virus (44), and with HIV-1, glycan and conformational masking play dominant roles (11, 45). Partial solutions such as those presented by antibody b12 (neutralization of 40% of circulating isolates) (22) or by antibody HJ16 (neutralization of 30% of circulating isolates) (46), a recently identified CD4-binding-site antibody, may allow recognition of some HIV-1 isolates.

With VRC01, the breadth and potency of neutralization (over 90%) suggests a more general solution. Here we see that this solution involves two features: partial receptor mimicry and extensive affinity maturation. It remains to be seen how difficult it will be to guide the elicitation of VRC01-like antibodies from genomic rearrangement, through affinity maturation, to broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1. Accumulating evidence suggests that the VRC01-defined mode of recognition is used by other antibodies, from the same individual (VRC02 and VRC03) (12) as well as from other individuals (Wu and Mascola, personal communication). These findings suggest that VRC01 is not an isolated example, and likely provides a template for a general mode of recognition. The structure-function insights of VRC01 described here thus provide a foundation for rational vaccine design based not only on the particular mode of antibody-antigen interaction, but also on defined relationships between genomic antibody precursors, somatic hypermutation, and required interface elements.

Supplementary Material

References and Notes

- 1.Weiss RA, et al. Nature. 1985 Jul 4-10;316:69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascola JR, Montefiori DC. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010 Mar;28:413. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton DR. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002 Sep;2:706. doi: 10.1038/nri891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton DR, et al. Nat Immunol. 2004 Mar;5:233. doi: 10.1038/ni0304-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 require non-specific membrane interaction (34-35), antibody 2G12 recognizes carbohydrate and is domain swapped (32-33), and antibody b12 was originally derived by phage display and has heavy-chain-only recognition (22).

- 6.Dhillon AK, et al. J Virol. 2007 Jun;81:6548. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02749-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, et al. J Virol. 2009 Jan;83:1045. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01992-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, et al. Nat Med. 2007 Sep;13:1032. doi: 10.1038/nm1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binley JM, et al. J Virol. 2008 Dec;82:11651. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01762-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sather DN, et al. J Virol. 2009 Jan;83:757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, et al. Science. 2009;326:1123. doi: 10.1126/science.1175868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu X, et al. Science. 2010 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Env components of this strain derive from Clade E HIV-1 lineages (47).

- 14.Pancera M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jan 19;107:1166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911004107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The four independent copies of the VRC01-gp120 complex in the asymmetric unit resembled each other closely for the antibody variable domain-gp120 components, with an Cα-root-mean-square deviation of less than 0.2 Å. Elbow variation, however, between variable and constant domains was apparent, and we found one copy (molecule 1) to be more ordered than the others. In figures, we display molecule 1; see Fig. S10 for a comparison of all molecules per asymmetric unit.

- 16.Surface areas of interaction reported in this paper were determined with the program PISA, as implemented in CCP4 (48). Values were about 20% higher than those reported previously for the gp120-CD4 complex (18), which were obtained using the program MS (49).

- 17.Maddon PJ, et al. Cell. 1985 Aug;42:93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwong PD, et al. Nature. 1998 Jun 18;393:648. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The overlap of molecular volumes was calculated by comparing the separate volumes of interacting domains with the combined volume of these domains after gp120 superposition.

- 20.The relative orientation of the light chain variable domain and the heavy chain variable domain of VRC01 is similar to that of other antibodies (Fig. S11).

- 21.Rits-Volloch S, Frey G, Harrison SC, Chen B. EMBO J. 2006 Oct 18;25:5026. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou T, et al. Nature. 2007 Feb 15;445:732. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finzi A, et al. Mol Cell. 2010 Mar 12;37:656. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiang SH, et al. J Virol. 2002 Oct;76:9888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9888-9899.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwong PD, et al. Nature. 2002 Dec 12;420:678. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu X, et al. J Virol. 2009 Nov;83:10892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01142-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endo H treatment of gp120 prior to deglycosylation removed all but the protein-proximal N-acetyl-glucosamine and potential 1,6-fucose from sites of N-linked glycosylation. Examination of the VRC01 interactions with the N-acetyl-glycosamine at residue 276gp120 shows that both 1,4 additions and 1,6 additions are tolerated.

- 28.Scheid JF, et al. Nature. 2009 Apr 2;458:636. doi: 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang CC, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 2;101:2706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308527100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Wildt RM, Hoet RM, van Venrooij WJ, Tomlinson IM, Winter G. J Mol Biol. 1999 Jan 22;285:895. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Four residues are provided by the CDR H3, Asp99VRC01-Trp100BVRC01, with a combined interactive surface of 123 Å2 (Tables S3B and S8). These four residues are likely contributed by the D segment (IGHD3-16*02) (Fig. S9), and none of them appears critical to VRC01 recognition, as changes are observed in two of these residues in the closely related broadly-neutralizing antibody VRC03, which was one of two somatically related antibodies we isolated along with VRC01 (12). Meanwhile, three residues are provided by the CDR L3, Tyr91VRC01, Glu96VRC01 and Phe97VRC01, with a combined interactive surface of 190 Å2 (Tables S3b and S9). These three residues lie at the junction between V- and J-genes. They make important hydrophobic interactions with loop D of gp120, and two of them are conserved between VRC01 and VRC03. While it is difficult to know how precisely the CDR L3 needs to be aligned, with only three contact residues, variation at the VΚ-J gene junction should provide sufficient diversity for it to be represented in the repertoire.

- 32.Sanders RW, et al. J Virol. 2002 Jul;76:7293. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7293-7305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calarese DA, et al. Science. 2003 Jun 27;300:2065. doi: 10.1126/science.1083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ofek G, et al. J Virol. 2004 Oct;78:10724. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10724-10737.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haynes BF, et al. Science. 2005 Jun 24;308:1906. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berek C, Berger A, Apel M. Cell. 1991 Dec 20;67:1121. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90289-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Analysis of the HIV-1 Env-reactive antibody repertoire from infected individuals shows increased levels of affinity maturation (28). Analysis of a subset of this data containing 147 heavy and 147 light chains from HIV-1 Env-reactive antibodies reveals an average of 15 alterations (30 maximum) for the heavy chain and an average of 8.6 alterations (22 maximum) for the light chain (SOM Appendix). In terms of the subset of HIV-1 Env-reactive antibodies that are broadly neutralizing (e.g. 2G12, 2F5, 4E10 and b12), antibodies b12 and 2G12 have 45 and 51 changes, respectively, relative to nearest genomic precursors in their VH- and J-segments of the heavy chain (29).

- 38.EC50 measurements were used for affinity measurements, as surface-plasmon resonance measurements were inaccurate for VRC01 variants where affinity was weak. Good correlations however were observed between surface-plasmon resonance measured KD and ELISA-determined EC50s (Fig. S12B).

- 39.Xiao X, Chen W, Feng Y, Dimitrov DS. Viruses. 2009;1:802. doi: 10.3390/v1030802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao X, et al. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009 Dec 18;390:404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimitrov DS. MAbs. 2010 May 14;2 doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.5.12570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossmann MG. J Biol Chem. 1989 Sep 5;264:14587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith TJ, Chase ES, Schmidt TJ, Olson NH, Baker TS. Nature. 1996 Sep 26;383:350. doi: 10.1038/383350a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiley DC, Wilson IA, Skehel JJ. Nature. 1981 Jan 29;289:373. doi: 10.1038/289373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wyatt R, et al. Nature. 1998 Jun 18;393:705. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corti D, et al. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson JP, et al. J Virol. 2000 Nov;74:10752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10752-10765.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.N. Collaborative Computational Project. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994 Sep 1;50:760. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Connolly ML. J Mol Graph. 1993 Jun;11:139. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(93)87010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Nature. 2008 Sep;4554:109. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Author contributions: T.Z., I.G., Z.Y., J.Sodroski, L.S., G.J.N., J.R.M., and P.D.K. designed research; T.Z., I.G., X.W., Z.Y., K.D. A.F., W.S., L.X., Y.Y. and J.Z. performed research; X.W., Y.K., J.Scheid, M.C.N. and J.R.M. contributed new reagents or reference data; T.Z., I.G., X.W., J.S., L.S., G.J.N., J.R.M. and P.D.K analyzed the data; T.Z., I.G., J. Sodroski, L.S., G.J.N., J.R.M. and P.D.K. wrote the paper, on which all authors commented.

- 52.Acknowledgments: We thank I.A. Wilson and members of the Structural Biology Section and Structural Bioinformatics Core, Vaccine Research Center, for discussions and comments on the manuscript, and J. Stuckey for assistance with figures. Support for this work was provided by grants from the NIH and from the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH. Use of sector 22 (Southeast Region Collaborative Access team) at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under contract no W-31-109-Eng-38.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.