Abstract

Background and Objective

The most recent American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement clearly supports breastfeeding for smoking mothers. The impact of this recommendation on pediatricians' counseling and prescribing practices is unclear. This study describes Pennsylvania pediatricians' attitudes, knowledge, and practices regarding breastfeeding, maternal smoking, and smoking cessation.

Methods

A descriptive study was conducted using a web-based, anonymous survey. The survey consisted of three clinical vignettes followed by knowledge and attitude questions.

Results

Among 296 respondents, more than half reported one or more conversations about breastfeeding and smoking in the past year. Most were comfortable counseling on breastfeeding, but few were comfortable counseling about smoking and breastfeeding. Respondents scored poorly on five knowledge items; 27% answered zero items correctly, and only 21% answered four or five items correctly. Less than half reported breastfeeding was safe for smoking mothers. Compared to pediatricians with high knowledge scores, those with a low score were less likely to tell a smoking mother that breastfeeding is safe (38% vs. 69%, p < 0.01) and more likely to recommend formula feeding (19% vs. 3%, p < 0.01). Most pediatricians were uncertain about the safety of nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion (Zyban®, GalxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) with breastfeeding.

Conclusions

Pennsylvania pediatricians lack knowledge and comfort related to the topic of breastfeeding and maternal smoking. Additional efforts to inform and educate pediatricians on the subjects of breastfeeding, maternal tobacco use, and smoking cessation products are needed.

Introduction

Awoman's choice to breastfeed may be impacted by her smoking status. Studies have shown that breastfeeding initiation and duration rates are lower for smokers.1–5 The lower rates are not accounted for by physiological differences,6 suggesting that attitudes about the safety of breastfeeding and smoking may impact decisions to breastfeed. In the early to mid-1990s, reported smoking rates among pregnant women approached 20%.7 Although up to 40% of smoking women quit during pregnancy, the majority resume smoking in the postpartum period.8–11

Until 2001, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) breastfeeding policy statements classified nicotine as a “drug of abuse contraindicated during breastfeeding.”12–14 The classification was based on study findings that nicotine use was associated with decreased milk production, slower infant weight gain, and exposure of the infant to environmental tobacco smoke.15 Based upon the published literature and the AAP recommendations, physicians likely discouraged smoking mothers from breastfeeding.

Throughout the 1990s, evidence in support of breastfeeding for smoking mothers increased. In 2000, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued the “HHS Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding.” In the section addressing tobacco consumption it stated, “for women who cannot or will not stop smoking, breastfeeding is still advisable, since the benefits of breast milk outweigh the risks from nicotine exposure.”16 Beginning with the 2001 AAP policy statement, “The Transfer of Drugs and Other Chemicals into Human Milk,” nicotine was removed from the tables of drugs contraindicated during breastfeeding.15 In the 2005 policy statement, “Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk,” the AAP supported the continuation of breastfeeding among mothers who smoke by stating definitively that smoking is not a contraindication to breastfeeding.17 Other organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and World Health Organization, have made similar recommendations. There is growing evidence that the incidence of acute respiratory illnesses in breastfed infants of smoking mothers are decreased compared to formula-fed infants of smoking mothers and there are no difference in infant weight gain.18–20

Improving maternal smoking cessation rates and breastfeeding rates are important challenges for many states, including Pennsylvania. Nationwide, 8–35% of breastfeeding mothers are smokers.21,22 Studies by the Annie E. Casey Foundation ranked Pennsylvania cities among the worst in the nation for maternal smoking rates for more than a decade.23–25 While Pennsylvania has high rates of smoking during pregnancy, it has lower rates of breastfeeding initiation (71%) and duration at 6 months (36%) than national rates and the Healthy People 2010 objectives.26 Pediatricians have an opportunity to both promote breastfeeding and smoking cessation and may be called upon to give advice regarding smoking cessation and the safety of breastfeeding for smoking mothers. It is unclear what impact the most recent policy statements have had on pediatricians' approach to these important topics.

The goals of this study were (1) to describe Pennsylvania pediatricians' attitudes and knowledge regarding concurrent breastfeeding and smoking or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), (2) to assess familiarity with current AAP and AAFP breastfeeding guidelines, (3) to examine counseling and prescribing practices regarding breastfeeding and smoking cessation products, and (4) to identify the resources most commonly used to answer breastfeeding questions.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

This descriptive study was conducted among physician members of the Pennsylvania chapter of the AAP (PA-AAP) who had provided the organization with an e-mail address. Permission was obtained from the PA-AAP to solicit its members for this study. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board granted exempt approval for this study.

Survey

The medical literature was reviewed for previously validated questions related to smoking and breastfeeding; no prior surveys were identified. Therefore the authors developed questions based upon study aims.

The questionnaire was pretested, revised, and then pretested again from October 2004 to April 2005 by physician members of the General Academic Pediatrics Division at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, resident physicians in Pediatrics and Medicine-Pediatrics, several physicians with expertise in either breastfeeding or smoking, and an expert in survey methods. During pretesting, evaluators were asked to complete a paper version of the survey. Evaluators reported that the questionnaire was completed in approximately 10–15 minutes. The comments of the evaluators resulted in minor changes to the questionnaire.

The questionnaire was organized into four sections. The first section consisted of three clinical vignettes that were followed by three or four questions to assess the physician's attitude, knowledge level, or most likely practice for the specific breastfeeding and smoking scenario. The second section consisted of multiple choice and Likert scale questions. Participants rated both their comfort level in counseling mothers about breastfeeding in general and breastfeeding and concurrent smoking. Comfort was measured using a 10-point Likert scale, with 1 being “not at all comfortable” and 10 being “extremely comfortable.” The importance of breastfeeding and smoking in the physician's clinical practice and the familiarity with the most recent AAP and AAFP guidelines and policy statements on breastfeeding were also evaluated. The third section, which contained true/false and multiple choice questions, assessed physician knowledge and resources physicians use to answer breastfeeding questions. Knowledge questions included preferred timing of breastfeeding in relation to smoking, effect of smoking on breastmilk supply, expected serum nicotine levels in nicotine patch users compared with smokers, and knowledge of the recommendations regarding breastfeeding and smoking in AAP and AAFP policy statements. The fourth section assessed sample demographics and personal tobacco and breastfeeding history.

The PA-AAP sent three e-mail invitations (in August, September, and October 2005) to participate; the e-mail contained an active link to the online survey (SurveyMonkey). The program allowed participants to complete the survey over multiple sessions, if desired, but each participant was only allowed to complete a single survey. At the end of the survey, links were provided to the AAP, AAFP, and Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine websites and to the policy/position statements of the AAP and AAFP. Survey data were transmitted anonymously, without participant identifiers, to the investigators for analysis.

Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 10.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were utilized to evaluate responder characteristics, knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practices. Comparisons of attitudes, practices, and knowledge by gender, age, race, years in practice, practice location, work schedule, and responder's breastfeeding history and smoking status were also performed. Student's t test was used to compare continuous variables. χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables.

Results

Sample

Among 1,808 eligible PA-AAP members, 296 completed the survey (response rate, 16.4%). Characteristics of survey respondents are described in Table 1. Over half the respondents were female, under 40 years of age, and Caucasian. The majority were employed full-time, had been in practice less than 10 years, spent at least three-quarters of their time in clinical activities, practiced in an urban setting, and routinely saw newborns in their practice. Most had never been smokers, and their partner/spouse never smoked. Among respondents with children, most reported that all their children were breastfed.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents in a Breastfeeding and Smoking Survey of Pennsylvania Pediatricians in 2005 (n = 296)

| Characteristic | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <30 | 17 |

| 30–39 | 38 |

| 40–49 | 26 |

| ≥50 | 19 |

| Years in practice | |

| <5 | 42 |

| 5–9 | 18 |

| 10–19 | 21 |

| ≥20 | 19 |

| Gender female | 65 |

| Race | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 82 |

| Asian | 11 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 |

| African American | 3 |

| Other | 2 |

| Smoker? | |

| Never | 87 |

| Former | 12 |

| Current | <1 |

| Partner/spouse smoker? | |

| Never smoker | 77 |

| Former smoker | 13 |

| Current smoker | 2 |

| No partner/spouse | 8 |

| Children breastfed?a | |

| All breastfed | 83 |

| Some breastfed | 10 |

| None breastfed | 7 |

| Work schedule | |

| Full-time | 80 |

| Part-time | 17 |

| Unemployed/not practicing | 2 |

| Retired | <1 |

| Practice location | |

| Urban, inner city | 42 |

| Urban, not inner city | 19 |

| Suburban | 29 |

| Rural | 10 |

| Work time spent in clinical activities | |

| >75% | 68 |

| 51–75% | 13 |

| ≤50% | 19 |

| Newborn in practice | |

| Yes, routinely see newborns | 92 |

Among the 194 respondents with children.

Attitudes and knowledge of breastfeeding, smoking, and NRT

Less than half of the respondents reported that breastfeeding was safe for smoking mothers, and most physicians were uncertain about the safety of NRT or bupropion (Zyban®, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) with breastfeeding (Table 2). In responding to the five knowledge questions, 27% did not answer any question correctly, and only 21% answered four or five questions correctly. More than two-thirds (68%) were unsure or incorrect about the safest time to breastfeed in relation to smoking, and over half (53%) were unsure about the effect of smoking on milk supply. There were no differences in the number of questions answered correctly by physician gender, age, years in practice, practice location, or work schedule.

Table 2.

Attitudes on the Safety of Breastfeeding with Maternal Smoking, NRT, and Bupropion in a Breastfeeding and Smoking Survey of Pennsylvania Pediatricians in 2005 (n = 296)

| Physician opinion/recommendation | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Breastfeeding safe regardless of the amount a mother smokes | 49 |

| Breastfeeding safe only if mother smokes less than 1/2 pack/day | 16 |

| Breastfeeding safe only if mother smokes less than 1 pack/day | 2 |

| Formula feeding safest for infant of smoking mother | 17 |

| No specific opinion/recommendation, leave decision to mother | 16 |

| All forms of NRT safe with breastfeeding | 15 |

| Only over-the-counter NRT (e.g., nicotine gum or patch) safe with breastfeeding | 1 |

| Only prescription NRT (e.g., nicotine nasal spray or inhaler) safe with breastfeeding | 0 |

| No form of NRT safe with breastfeeding | 5 |

| Unsure of the safety of NRT with breastfeeding | 79 |

| Safe to breastfeed while taking bupropion (Zyban) | 10 |

| Not safe to breastfeed while taking bupropion (Zyban) | 8 |

| Not enough data available | 13 |

| Unsure of the safety of bupropion (Zyban) with breastfeeding | 69 |

Familiarity with breastfeeding guidelines

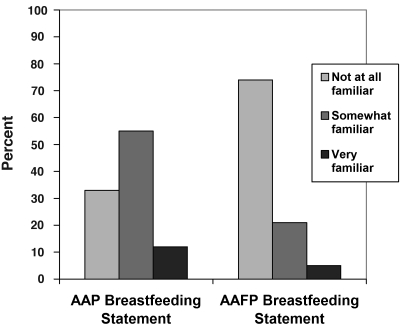

Nearly one-third of respondents reported they were not familiar with the 2005 AAP Breastfeeding policy statement. Fewer still were familiar with the AAFP Policy Statement on Breastfeeding, with nearly three-quarters reported being “not at all familiar” (Fig. 1). The level of familiarity with the guidelines was not associated with reported counseling practices (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Familiarity with breastfeeding guidelines in a breastfeeding and smoking survey of Pennsylvania pediatricians in 2005 (n = 296).

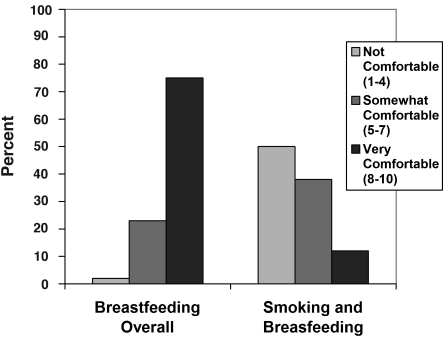

Counseling and prescribing practices

Over 50% of respondents recalled at least one conversation with mothers about smoking and breastfeeding in the past year, and nearly 10% reported more than 10 discussions. Overall, responders were very comfortable counseling about breastfeeding in general; 75% rated their comfort level as 8 or above (on a 1–10 scale). Comfort levels were much lower for counseling on smoking and breastfeeding; 50% rated their comfort level 4 or below, and only 12% rating their comfort level as 8 or above (Fig. 2). More male respondents reported being “very comfortable” counseling on smoking and breastfeeding than female respondents (20% vs. 8%, p < 0.01). Physicians with more than 5 years in practice were more likely to be “very comfortable” than were those in practice less than 5 years (17% vs. 5%, p < 0.01). Compared to pediatricians who scored high (4 of 5 or 5 of 5 correct) on knowledge questions, those who scored poorly (0 of 5 or 1 of 5 correct) were less likely to counsel a mother who smokes that it is safe to breastfeed exclusively (38% vs. 69%, p < 0.01) and more likely to recommend that she formula feed (19% vs. 3%, p < 0.01, Table 3). Physicians with high knowledge scores were more likely to advise a smoking mother that NRT was safe with breastfeeding compared with those who scored poorly (26% vs. 9%, p = 0.01, Table 3). Pediatricians with less than 5 years in practice were more likely to counsel that breastfeeding is safe for smoking mothers than were the respondents with more than 5 years in practice (60% vs. 41%, p < 0.001). Pediatricians practicing in urban, inner-city locations were more likely to recommend discontinuation of breastfeeding to smoking mothers than were physicians practicing in other locations (23% vs. 13%, p = 0.01).

FIG. 2.

Counseling comfort (self-reported scale of 1–10) in a breastfeeding and smoking survey of Pennsylvania pediatricians in 2005 (n = 296).

Table 3.

Breastfeeding Advice Given to a Smoking Mother by Physician Knowledge Level in a Breastfeeding and Smoking Survey of Pennsylvania Pediatricians in 2005 (n = 296)

| |

Knowledge levela |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advice (%) | Poor (0/5 or 1/5) | Intermediate (2/5 or 3/5) | High (4/5 or 5/5) | p |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 38 | 56 | 69 | |

| Partial breastfeeding | 25 | 21 | 21 | |

| Discontinue breastfeeding, only formula feeding | 19 | 17 | 3 | <0.01 |

| No specific recommendation | 18 | 6 | 7 | |

| NRT safe with breastfeeding | 9 | 16 | 26 | 0.01 |

To measure physician knowledge, in this scenario a breastfeeding mother of a 2-month-old infant recently returned to smoking and asked the pediatrician for advice on whether to continue breastfeeding and whether NRT was safe with breastfeeding.

Based on a total of five knowledge questions.

Most respondents refer breastfeeding mothers to their primary care or obstetric provider for smoking cessation recommendations or prescriptions (73%). Pediatricians favored behavioral programs for smoking cessation (72%) over NRT, bupropion, and “cold turkey” quit attempts. Very few providers in this survey would write a prescription for NRT (5%) or bupropion (1.4%) for a breastfeeding mother. The pediatrician's gender, age, race, work schedule, smoking history, or personal history with breastfeeding was not associated with the number of breastfeeding and smoking discussions reported, counseling practices, or willingness to prescribe NRT or bupropion.

Breastfeeding resources

A number of breastfeeding resources were reported by respondents. The most commonly used resources were Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation by Briggs et al.27 (48%), Medications and Mother's Milk by Hale28 (43%), Physicians' Desk Reference29 (41%), the Harriet Lane Handbook30 (33%), and the Epocrates website31 (21%). Less commonly reported breastfeeding resources included AAP policy statements, the Lexi-Comp website,32 and Neonatology33 in the Lange Clinical Manuals Series.

Discussion

This is the first study designed specifically to investigate pediatricians' attitudes, knowledge, and practices regarding concurrent breastfeeding and maternal smoking. We found that while most respondents were comfortable discussing breastfeeding in general, they were much less comfortable discussing breastfeeding in the context of maternal smoking.

Recommending and prescribing of medications to parents has long been a controversial issue for pediatricians. Findings in our study were similar to those of Oncken et al.,34 in which only 11% of pediatricians sampled reported they would recommend or prescribe NRT for pregnant or lactating smokers. Surveys of adult smokers have also reported low rates of smoking cessation medication recommendations and prescriptions to parental smokers during child healthcare visits. In one study, 15% of smoking parents had pharmacotherapy recommended, and 8% received a prescription for a smoking cessation medication by their child's physician.35 The 2004 AAP periodic survey found that pediatricians reported parental smoking cessation and harm reduction from tobacco smoke more important than in prior years but reported less confidence in their abilities to provide guidance and perceived less effectiveness in changing parents' behavior.36 The same survey found that 27% of pediatricians recommend NRT to patients who smoke, 26% recommend NRT to parents who smoke, but that 10% prescribe NRT to patients (8%) or parents (6%).37 Although prescribing of medications to parents will likely remain a controversial practice for pediatricians, efforts to improve comfort and confidence in delivering smoking cessation messages are clearly needed.

Pediatricians in this survey reported using a number of different breastfeeding resources. The Physicians' Desk Reference29 was cited by over 40% of respondents. While the Physicians' Desk Reference29 is a good general pharmaceutical reference, it is considered a poor source of information about the potential effects of medications on a lactating mother or her infant.38 It contains information from package inserts produced by pharmaceutical manufacturers, based on their product studies. Since manufacturers rarely conduct their own studies on lactating women, package inserts generally recommend that the medication not be taken while breastfeeding, even when studies have been done by others. Physicians should be aware of this limitation and utilize resources that contain more comprehensive lactation safety information. The National Library of Medicine Drugs and Lactation Database, LactMed, is a reliable and free online resource.39

Although the AAP and other organizations encourage discussions with mothers regarding breastfeeding, smoking, and smoking cessation, there have been no formal recommendations regarding NRT or other smoking cessation techniques for breastfeeding women. Studies in nonpregnant smokers have shown that these types of therapies double smoking cessation rates compared with placebo.40–43 No clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate the benefit versus risk of nicotine replacement products for breastfeeding mothers and the most recent U.S. Public Health Service clinical practice guideline advises that use of medications for tobacco dependence may not be appropriate in some patient groups, including breastfeeding women.43 However, when used correctly, the daily dose of nicotine with NRT is no more than (or lower than) one pack per day smoking. Therefore, when used properly, the nicotine concentration in milk is expected to be lower than a pack per day cigarette smoking.44 Additionally, NRT (specifically the nicotine patch) has no significant influence on infant milk intake.45 Lactation and medication experts advise that physicians who recommend NRT products to lactating mothers should counsel them to avoid fast-acting products, like nicotine gum or nasal spray, 2–3 hours prior to and during each feeding. Women who use transdermal systems should remove the nicotine patch at bedtime to reduce exposure of the infant.28,44 Additional studies are needed to evaluate the safety of these products for breastfeeding women, especially since NRT is available over-the-counter and breastfeeding women may choose to use these products without consulting their physician.

Two non-nicotine medications are currently available for the treatment of tobacco dependence. Bupropion (Zyban) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as a smoking cessation treatment in 1997, and Varenicline (Chantix®, Pfizer, New York, NY) was approved in May 2006. There are very limited published data on these medications in breastfeeding mothers. Varenicline (Chantix) has not been studied in pregnant or breastfeeding women, and there are only a handful of studies that have reported on bupropion in breastmilk or breastfed infants.46–49 Because Varenicline (Chantix) was not approved at the time of our study, it was not included in the survey. When more definitive information is available regarding the safety of NRT and the non-nicotine prescription medications for smoking cessation, recommendations on the use of these products should be incorporated into breastfeeding guidelines.

There were several limitations to this study. Physicians were recruited from a single state by e-mail invitation to complete the online survey, which could bias sample selection toward younger and more computer-savvy physicians or physicians who have an interest in breastfeeding promotion. Because PA-AAP could not provide us with demographic data on physicians in their database, we could not compare characteristics of physician respondents to the members at large. A majority of our respondents were female and under 40 years of age, which may not be representative of the PA-AAP membership. Furthermore, because the survey was limited to Pennsylvania pediatricians it may not be generalizable to all pediatric providers. The response rate was low, likely because of the e-mail method of participant solicitation. We were not able to assess what proportion of the e-mail addresses was active. Including other practitioners who counsel women on breastfeeding and smoking cessation, such as family physicians and obstetricians, would have been informative; however, we were not able to obtain access to other e-mail databases without a fee.

Pennsylvania continues to have high maternal smoking rates, with Pittsburgh and Philadelphia among the worst cities in the nation for maternal smoking.23–25 Pediatricians in Pennsylvania, and other areas with high maternal smoking rates, can reasonably expect to receive questions from mothers who smoke regarding both smoking cessation and breastfeeding. Pennsylvania practitioners should be aware of Pennsylvania's Tobacco Prevention and Control Program, including the 24-hour Free Quitline. Many other states have similar smoking cessation resources available, and the national quitline, 1-800-QUIT-NOW, is another resource physicians can utilize. The study of Bogen et al.50 found that mothers are equally as likely to ask their own physician as their child's physician for advice on smoking and breastfeeding. Other studies have found that most parents believe it is an important part of a pediatrician's job to ask about a parent's smoking status.51 Surveys of smoking parents have found that most want some kind of smoking cessation help from the pediatrician's office, and the majority feel it would be acceptable if their child's doctor prescribed or recommended it to them.35,51 Improving pediatricians' willingness to have these discussions during child health visits could lead to improvements in both breastfeeding and smoking cessation rates.

Pediatricians need to be comfortable and confident when delivering breastfeeding and smoking cessation advice. Pediatric care providers need to keep informed of the most updated breastfeeding guidelines, recommendations, and resources. There are many potential barriers to physician adherence to clinical practice guidelines.52 A number of these barriers were confirmed in this study, including lack of awareness, lack of familiarity, and lack of self-efficacy. Other barriers may have been present but were not specifically examined in this questionnaire. Additional emphasis should be placed on effective dissemination of clinical guideline information and improving physician adherence to published guidelines.

Conclusions

This survey found that pediatricians lack knowledge and comfort regarding issues related to breastfeeding and maternal smoking. Surveyed physicians reported lower comfort levels for discussions related to breastfeeding and maternal smoking compared with general breastfeeding discussions. Additionally, pediatricians lacked knowledge in regards to smoking, NRT, or bupropion (Zyban) with breastfeeding. Many were also unfamiliar with the most recent breastfeeding guidelines and policy statements. Additional efforts to inform and educate pediatricians on the subjects of breastfeeding, maternal tobacco use, and smoking cessation products are needed.

Footnotes

Study findings were presented at the 2006 Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting, May 2006, San Francisco, California; the 2006 University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Day, May 2006, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and the 11th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, September 2006, Niagara Falls, New York.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a resident research award grant from the Ambulatory Pediatric Association to C.A.L. D.L.B.'s contribution to this work was supported in part by K12 HD043441 (BIRCWH Award). D.R.M.'s and W.C.B.'s contribution was in part supported by a grant from Tobacco Free Allegheny. We would like to thank Karen E. Bogen, Ph.D., Jennifer Green, M.D., and Lanna Kwon, M.D., for their expert review of the survey design.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ever-Hadani P. Seidman DS. Manor O, et al. Breast feeding in Israel: Maternal factors associated with choice and duration. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48:281–285. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards N. Sims-Jones N. Breithaupt K. Smoking in pregnancy and postpartum: Relationship to mothers' choices concerning infant nutrition. Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30:83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horta BL. Kramer MS. Platt RW. Maternal smoking and the risk of early weaning: A meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:304–307. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J. Rosenberg KD. Sandoval AP. Breastfeeding duration and perinatal smoking in a population-cased cohort. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:309–314. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giglia RC. Binns CW. Alfonso HS, et al. Which mothers smoke before, during and after pregnancy? Public Health. 2007;121:942–949. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amir LH. Donath SM. Does maternal smoking have a negative physiological effect on breastfeeding? The epidemiological evidence. Breastfeeding Rev. 2003;11:19–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annie E Casey Foundation. KIDS COUNT, The Right Start for America's Newborns, State-Level Data Online, Births to Mothers Who Smoked During Pregnancy. 1990. www.kidscount.org/datacenter/compare_results.jsp?i=45&dt=2&yr=1&s=a&x=187&y=8. [Sep 9;2008 ]. www.kidscount.org/datacenter/compare_results.jsp?i=45&dt=2&yr=1&s=a&x=187&y=8

- 8.Fang WL. Goldstein AO. Butzen AY, et al. Smoking cessation in pregnancy: A review of postpartum relapse prevention strategies. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:264–275. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.4.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullen PD. How can more smoking suspension during pregnancy become lifelong abstinence? Lessons learned about predictors, interventions, and gaps in our accumulated knowledge. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;(Suppl 2):S217–S238. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suellentrop K. Morrow B. Williams L, et al. Monitoring progress toward achieving Maternal and Infant Healthy People 2010 objectives—19 states, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2000–2003. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(9):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Röske K. Hannöver W. Grempler J, et al. Post-partum intention to resume smoking. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:386–392. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human breast milk. Pediatrics. 1983;72:375–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 1989;84:924–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 1994;93:137–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108:776–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding, Washington, D.C. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health. 2000. www.4women.gov/breastfeeding/bluprntbk2.pdf. [Sep 9;2008 ]. www.4women.gov/breastfeeding/bluprntbk2.pdf

- 17.Gartner LM. Morton J. Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodward A. Douglas RM. Graham NM, et al. Acute respiratory illness in Adelaide children: Breast feeding modifies the effect of passive smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1990;44:224–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.44.3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boshuizen HC. Verkerk PH. Reerink JD, et al. Maternal smoking during lactation: Relation to growth during the first year of life in a Dutch birth cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:117–126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chantry CJ. Howard CR. Auinger P. Full breastfeeding duration and associated decrease in respiratory tract infection in US children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:425–432. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luck W. Nau H. Nicotine and cotinine concentrations in serum and milk of nursing smokers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;18:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb05014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labrecque M. Marcoux S. Weber JP, et al. Feeding and urine cotinine values in babies whose mothers smoke. Pediatrics. 1989;83:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wertheimer R. O'Hare W. Croan T, et al. Child Trends/KIDS COUNT Working Paper. Child Trends, Inc., Washington, DC. Annie E. Casey Foundation; Baltimore, MD: 2001. [Sep 9;2008 ]. The Right Start for America's Newborns: A Decade of City and State Trends (1990–1999) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annie E Casey Foundation. KIDS COUNT, The Right Start for America's Newborns, City and State Trends, Pennsylvania. 1990–2005. www.kidscount.org/datacenter/profile_results.jsp?c=a&r=40&d=&n=&p=0&i=45#45. [Sep 9;2008 ]. www.kidscount.org/datacenter/profile_results.jsp?c=a&r=40&d=&n=&p=0&i=45#45

- 25.Annie E. Casey Foundation. KIDS COUNT, The Right Start for America's Newborns. City and State Trends, Philadelphia. 1990–2005. www.kidscount.org/datacenter/profile_results.jsp?r=319&d=1&c=rs. [Sep 9;2008 ]. www.kidscount.org/datacenter/profile_results.jsp?r=319&d=1&c=rs

- 26.Centers for Disease Control Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention Health Promotion Division of Nutrition Physical Activity. Breastfeeding: Data and Statistics: Breastfeeding Practices—Results from the 2005 National Immunization Survey, Geographic-Specific Breastfeeding Rates. 2005. www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.htm. [Sep 9;2008 ]. www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.htm

- 27.Briggs GG. Freeman RK. Yaffe SJ. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hale TW. Medications and Mothers' Milk. 10th. Pharmasoft Medical Publishers; Amarillo, TX: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Physicians' Desk Reference 2008. 62nd. Medical Economics Co.; Montvale, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Custer JW, editor; Rau RW, editor. Johns Hopkins: Harriet Lane Handbook. 18th. Elsevier Mosby; Philadelphia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.http://epocrates.com. [Sep 9;2008 ]. http://epocrates.com

- 32.www.lexi.com. [Sep 9;2008 ]. www.lexi.com

- 33.Gomella TL. Cunningham MD. Lange Clinical Manuals Series: Neonatology: Management, Procedures, On-Call Problems, Diseases, and Drugs. 5th. McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oncken CA. Pbert L. Ockene JK, et al. Nicotine replacement prescription practices of obstetric and pediatric clinicians. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:261–265. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winickoff JP. Tanski SE. McMillen RC, et al. Child health care clinicians' use of medications to help parents quit smoking: A national parent survey. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1013–1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanski SE. Winickoff JP. O'Connor KG, et al. Pediatricians' Tobacco Cessation Attitudes and Practices: Trends from 1994–2004 [abstract] AAP Division of Health Services Research. http://www.aap.org/research/abstracts/06abstract 15.htm. [Sep 9;2008 ]. http://www.aap.org/research/abstracts/06abstract 15.htm

- 37.AAP Division of Health Services Research. Pediatricians cite barriers to tobacco cessation counseling. AAP News. 2006;27(12):17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gotsch G. Maternal medications and breastfeeding. http://www.llli.org/NB/NBMarApr00p55.html. [Sep 9;2008 ];New Beginnings. 2000 17(2):55–56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institutes of Health. United States National Library of Medicine. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?LACT. [Sep 9;2008 ]. toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/htmlgen?LACT

- 40.Fiore MC. Smith SS. Jorenby DE, et al. The effectiveness of the nicotine patch for smoking cessation. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1994;271:1940–1947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henningfield JE. Nicotine medications for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1196–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline. JAMA. 1996;275:1270–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiore MC. Jaén CR. Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schatz BS. Nicotine replacement products: Implications for the breastfeeding mother. J Hum Lact. 1998;14:161–163. doi: 10.1177/089033449801400223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ilett KF. Hale TW. Page-Sharp M, et al. Use of nicotine patches in breast-feeding mothers: Transfer of nicotine and cotinine into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Briggs GG. Samson JH. Ambrose PJ, et al. Excretion of bupropion in breast milk. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:431–433. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baab SW. Peindl KS. Piontek CM, et al. Serum bupropion levels in 2 breastfeeding mother-infant pairs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:910–911. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haas JS. Kaplan CP. Barenboim D, et al. Bupropion in breast milk: an exposure assessment for potential treatment to prevent post-partum tobacco use. Tob Control. 2004;13(1):52–56. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaudron LH. Schoenecker CJ. Bupropion and breastfeeding: A case of a possible infant seizure. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:881–882. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0622f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bogen DL. Davies ED. Barnhart WC, et al. What do mothers think about concurrent breastfeeding and smoking? Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moss D. Cluss PA. Mesiano M, et al. Accessing adult smokers in the pediatric setting: What do parents think? Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(1):67–75. doi: 10.1080/14622200500431809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cabana MD. Rand CS. Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]