Abstract

Invertebrates are used extensively as model species to investigate neuro-endocrine processes regulating behaviors, and many of these processes may be extrapolated to vertebrates. However, when it comes to reproductive processes, many of these model species differ notably in their mode of reproduction. A point in case are simultaneously hermaphroditic molluscs. In this review I aim to achieve two things. On the one hand, I provide a comprehensive overview of the neuro-endocrine control of male and female reproductive processes in freshwater snails. Even though the focus will necessarily be on Lymnaea stagnalis, since this is the best-studied species in this respect, extensions to other species are made wherever possible. On the other hand, I will place these findings in the actual context of the whole animal, after all these are simultaneous hermaphrodites. By considering the hermaphroditic situation, I uncover a numbers of possible links between the regulation of the two reproductive systems that are present within this animal, and suggest a few possible mechanisms via which this animal can effectively switch between the two sexual roles in the flexible way that it does. Evidently, this opens up a number of new research questions and areas that explicitly integrate knowledge about behavioral decisions (e.g., mating, insemination, egg laying) and sexual selection processes (e.g., mate choice, sperm allocation) with the actual underlying neuronal and endocrine mechanisms required for these processes to act and function effectively.

Keywords: eggs, hermaphrodite, hormone, mollusc, neuropeptide, pulmonate, sexual selection, sperm

Introduction

Research into neurobiological and endocrine mechanisms of reproduction in animals has traditionally been used as a way to ultimately understand these processes in humans (e.g., Davison and Blaxter, 2005; Feng et al., 2009; Kemenes and Benjamin, 2009). As a result, in most model species the focus has been primarily on understanding male and female reproduction separately. Although this is a correct division for many vertebrate model species, for numerous invertebrate model species (e.g., molluscs) and some vertebrate species (e.g., fish) this separation largely ignores that many of these animals are hermaphroditic rather than gonochoric (separate sexes). Consequently, the complexity of being able to reproduce as male and female at the same time seems to have been underappreciated.

Given the above, this review has two aims. On the one hand, I provide a comprehensive overview of the neuro-endocrine control of male and female reproductive processes in hermaproditic freshwater snails (Order Basommatophora). On the other hand, I place these findings in the actual simultaneously hermaphroditic context of the whole animal. For simplicity, this context has often been left aside when concentrating on the neuro-endocrine regulation of one sexual function. However, clearly much can be gained by considering the hermaphroditic situation and the time is ripe for such integration. Therefore, I will explore a number of potential links between the regulation of the two reproductive systems of hermaphroditic gastropods, and suggest a few possible mechanisms via which these animals could switch between the two sexual roles in the flexible way that they do (e.g., Koene, 2006). Evidently, this opens up a number of new research questions and areas that explicitly integrate knowledge about behavioral decisions (e.g., mating, insemination, egg laying) and sexual selection processes (e.g., mate choice, sperm allocation) with the actual underlying neuronal and endocrine mechanisms required for these processes to act and function effectively (Koene et al., 2009a).

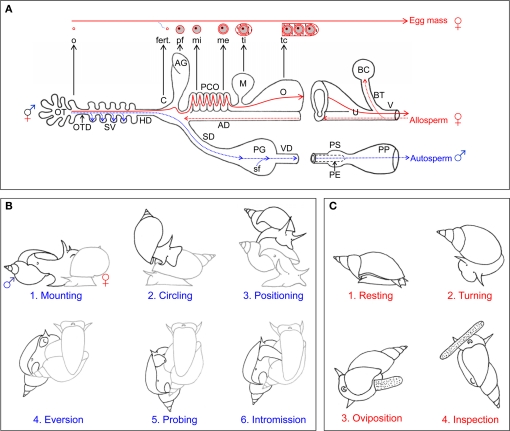

Male behavior of the basommatophoran species that have been investigated in detail typically contains a series of courtship events (shell mounting, circling, positioning, preputial eversion, probing) and ends in a unilateral copulation (penis eversion and intromission; see Van Duivenboden and Ter Maat, 1988; Jarne et al., 2010 and below). Sexual roles can be swapped afterward, but this is not a prerequisite for mating (i.e., does not necessarily imply sperm trading; e.g., Koene and Ter Maat, 2005). Since these animals have their male and female gonopores located on different parts of the body, mating chains or rings can also form (Chase, 2007). In such a chain, the frontmost individual acts only as a female, the last individual only as a male, and each individual in between acts as male to the partner directly in front of it and female to the partner directly in its back. In a few species simultaneously reciprocal matings may occasionally take place (reviewed in Jordaens et al., 2007 [Biomphalaria glabrata: Brumpt, 1941; Vernon and Taylor, 1996; Trigwell et al., 1997; Vianey-Liaud, 1998; B. tenogophila: Springer de Freitas et al., 1997; Helisoma trivolvis: Duncan, 1975]). In a standard unilateral copulation, the sperm recipient seems to be more or less inactive when mounted by a partner. However, studies that did specifically look at recipient behavior, currently limited to two species of Physa, found that there are ways of discouraging a mating partner once it has mounted on the shell, for example by vigorously swinging the shell back and forth (DeWitt, 1996; Wethington and Dillon, 1996; Facon et al., 2006). Egg laying is usually completely separated from insemination since most species can store allosperm and can self fertilize (e.g., L. stagnalis: Cain, 1956; B. glabrata: Vianey-Liaud et al., 1989, 1996). Egg laying itself seems to be influenced both by mating activity and environmental factors (L. stagnalis: Ter Maat et al., 1986; Koene et al., 2006; B. glabrata: Boyle and Yoshino, 2000) and is composed of a typical sequence of phases, starting with resting, followed by turning and oviposition, and ending with inspection of the egg mass (see Ter Maat et al., 1989 and below).

Because for neuronal and endocrinological aspects of reproductive behavior, research has mainly focused on the model species Lymnaea stagnalis, I will here review these findings and compare this to what is known in other species when possible. The male and female processes in the great pond snail L. stagnalis are controlled by different areas in the central nervous system and a multitude of substances are involved. These include members of several different neuropeptide families and at least one classic transmitter. Many of these neuropeptides are part of multipeptide precursor molecules, which are often evolutionarily conserved across molluscs. In the following sections I will review the male and female reproductive system and regulation separately, and subsequently bring these two together by looking at the potential mechanisms, based on current knowledge, that might be used to coordinate the expression of either sexual role.

Male Reproductive Behavior and Its Neuro-Endocrine Control

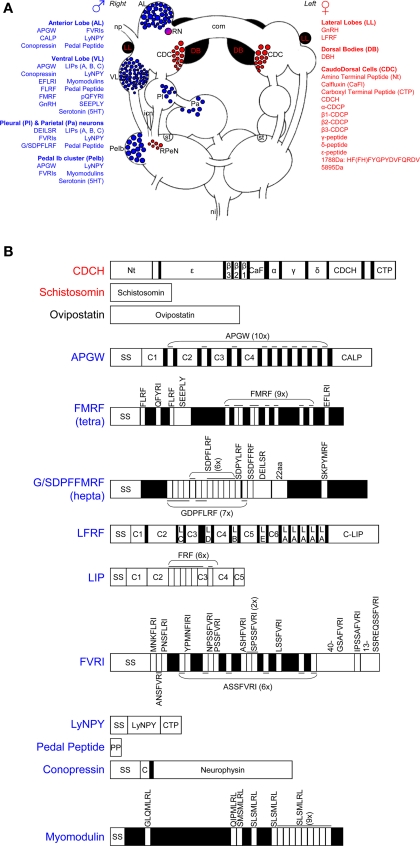

In L. stagnalis, the main centers for the control of male reproductive behavior are situated on the right side of the brain, reflecting the fact that the male organs are mostly located on the right side of the body, and come out via the male gonopore just behind the tentacle. As shown in Figure 1A, the main clusters of neurons are the anterior lobes (especially on the right side), right ventral lobe, right pedal Ib cluster, and some more dispersed cells in the right parietal and pleural ganglia (De Boer et al., 1996). Neurons in all these clusters project into the penial nerve, which is the only nerve that innervates the male copulatory organs. Backfills of the penial nerve of H. trivolvis reveal a very similar pattern (Young et al., 1999). The following will first briefly describe the involved neurons and their endocrinology (summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1), and subsequently how this fits in with the production of male behavior.

Figure 1.

Neuro-endocrine regulation of male and female reproduction in Lymnaea stagnalis. (A) Schematic drawing of the involved ganglia of the central nervous system. The blue and red areas show, respectively, the neuronal clusters that are involved in male and female reproduction. The substances involved in male reproduction are also indicated in blue; the female ones are listed in red. com, cerebral commissure; icn, inferior cervical nerve; ni, nervus intestinalis; np, nervus penis; RN, ring neuron; RPeN, right pedal neurons; st statocyst. This figure is adapted from Jarne et al. (2010). (B) Overview of the identified neuropeptides and proteins involved in reproduction. SS stands for signal sequence, numbered Cs stand for different connecting peptides, all the other peptides can be found in (A) of the figure. See text and Table 1 for further details and references.

Table 1.

Central and peripheral location of neuro-endocrine substances involved in male and female reproduction of hermaphroditic freshwater snails.

| Sex | Transmitter | Ganglion | Neuron cluster | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | APGW | Cerebral | Anterior lobe | Li et al. (1992); Smit et al. (1992); De Lange and Van Minnen (1998); Koene et al. (2000) | ||||

| Ventral lobe | Croll and Van Minnen (1992); De Lange et al. (1997) | |||||||

| Ring neuron | Croll and Van Minnen (1992) | |||||||

| Pedal | Ib cluster | De Lange et al. (1997) | ||||||

| Peripheral | Sensory preputium cells | De Lange et al. (1998a) | ||||||

| Conopressin | Cerebral | Anterior lobe | Smit et al. (1992); Croll and Van Minnen (1992); De Lange et al. (1997) | |||||

| Ventral lobe | Croll and Van Minnen (1992); De Lange et al. (1997) | |||||||

| Peripheral | Sensory preputium cells | De Lange et al. (1998a) | ||||||

| C-terminally located anterior lobe peptide (CALP) | Cerebral | Anterior lobe | Li et al. (1992); Smit et al. (1992) | |||||

| DEILSR | Pleural and Parietal | Dispersed neurons | Van Golen et al. (1995a); De Lange et al. (1998b) | |||||

| EFLRI | Cerebral | Ventral lobe | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a) | |||||

| FLRF | Cerebral | Ventral lobe | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a) | |||||

| FMRF | Cerebral | Ventral lobe | Schott and Boer (1982) | |||||

| FVRIs | Cerebral | Anterior lobe | El Filali et al. (2006) | |||||

| Pleural and Parietal | Dispersed neurons | |||||||

| Pedal | Ib cluster | |||||||

| G/SDPFLRF | Pleural and Parietal | Dispersed neurons | Van Golen et al. (1995a) | |||||

| Gonadotropin releasing hormone | Cerebral | Ventral lobe | Young et al. (1999) | |||||

| (GnRH) | Lateral lobes | |||||||

| Lymnaea inhibitory peptides (LIP A, B, C) | Cerebral | Ventral lobe | Van Golen et al. (1995a,b); Smit et al. (2003) | |||||

| Pleural and Parietal | Dispersed neurons | De Lange et al. (1998b) | ||||||

| Peripheral | Sensory preputium cells | De Lange et al. (1998a) | ||||||

| Lymnaea neuropeptide Y (LyNPY) | Cerebral | Anterior lobeVentral lobe Ventral lobe |

Croll and Van Minnen (1992); Smit et al. (1992); De Lange et al. (1997) | |||||

| Pleural and Parietal | Dispersed neurons | |||||||

| Pedal | Ib cluster | De Lange et al. (1997) | ||||||

| Myomodulins | Cerebral Pedal | Ventral lobe Ib cluster | Li et al. (1994a); Van Golen et al. (1996) | |||||

| Pedal peptide (PP) | Cerebral | Anterior lobe | Croll and Van Minnen (1992); De Lange et al. (1997) | |||||

| Ventral lobe | ||||||||

| Pleural and Parietal | Dispersed neurons | |||||||

| Peripheral | Sensory preputium cells | De Lange et al. (1998a) | ||||||

| pQFYRI | Cerebral | Ventral lobe | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a) | |||||

| SEEPLY | Cerebral | Ventral lobe | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a) | |||||

| Serotonin (5HT) | Pedal | Ventral lobe | Kemenes et al. (1989) | |||||

| Cerebral | Ib cluster | Elekes et al. (1988); Croll and Chiasson (1989); Kemenes et al. (1989); Hetherington et al. (1994) | ||||||

| Female | 1788Da: HF(FH)FYGPYDVFQRDV | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Jiménez et al. (2004) | ||||

| 5895Da | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Jiménez et al. (2004) | |||||

| Amino terminal peptide (Nt) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Calfluxin (CaFl) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Carboxyl terminal peptide (CTP) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Caudodorsal cell hormone (CDCH) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Caudodorsal cell peptide α (α-CDCP) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Caudodorsal cell peptide β1 (β1-CDCP) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Caudodorsal cell peptide β2 (β2-CDCP) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Caudodorsal cell peptide β3 (β3-CDCP) | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| Dorsal body hormone (DBH) | Supracerebral | Dorsal bodies | Joosse (1964); Geraerts and Joosse (1975); Wijdenes et al. (1983) | |||||

| LFRF | Cerebral | Lateral lobes | Hoek et al. (2005) | |||||

| Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) | Cerebral | Lateral lobes | Young et al. (1999) | |||||

| γ-Peptide | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| δ-Peptide | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) | |||||

| ε-Peptide | Cerebral | Caudodorsal cells | Geraerts et al. (1983, 1985); Vreugdenhil et al. (1988); Li et al. (1994b) |

Central and peripheral neuro-endocrinology of male function

Anterior lobe

The bilateral anterior lobes are located in the cerebral ganglia, and usually show a striking right-left asymmetry (see Figure 1A). In dextral species, the right lobe is bigger (e.g., Koene et al., 2000) and in sinistral species it is the left one (e.g., B. glabrata: Lever et al., 1965; L. stagnalis: Davison et al., 2009), in concordance with the side where the male organs are located. The different neuropeptides that have been reported to be present in the right anterior lobe are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1. APGW plays a key role in male copulatory behavior of gastropod molluscs (De Lange and Van Minnen, 1998; Koene et al., 2000) and is expressed in virtually all right anterior lobe neurons as well as in some on the left. This peptide is also found in the freshwater snail Bulinus truncatus (De Lange and Van Minnen, 1998). The APGW gene consists of 10 copies of APGW and one of C-terminally located anterior lobe peptide (CALP: Li et al., 1992; Smit et al., 1992, Figure 1B). APGW is co-expressed in anterior lobe neurons with either conopressin, the Lymnaea form of the neuropeptide tyrosine (LyNPY) or pedal peptide (Croll and Van Minnen, 1992; Smit et al., 1992; De Lange et al., 1997).

Ventral lobe

The ventral lobe is very prominent in the right cerebral ganglion of a dextral specimen of L. stagnalis (Figure 1A). The different substances found in this lobe are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1. FMRF is co-expressed with a number of the other peptides encoded on the same exon (Schott and Boer, 1982; Bright et al., 1993; Santama et al., 1993, 1995; Van Golen et al., 1995a; see Figure 1B). Furthermore, APGW, conopressin, LyNPY, and pedal peptide are all singly expressed in right ventral lobe neurons (Croll and Van Minnen, 1992; De Lange et al., 1997).

Pedal Ib cluster (peIb)

The pedal Ib cluster protrudes clearly from the right pedal ganglion of L. stagnalis (Figure 1A). There is abundant evidence that these cells are serotonergic (Elekes et al., 1988; Croll and Chiasson, 1989; Kemenes et al., 1989; Hetherington et al., 1994). All other substances observed in this cluster are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Dispersed cells in the right parietal and pleural ganglia

The cells dispersed in the right parietal and pleural ganglia (Figure 1A), sometimes referred to as B-neurons, have been shown to contain a number of different neuropeptides (see Figure 1 and Table 1). Not much more is known about these neurons, but some send branches into both the penial and intestinal nerve (De Boer et al., unpublished), which may imply a dual function that warrants further attention.

Innervation patterns

How the central nervous system regions control the male organs can, in part, be deduced from the projection of their axon fibers, which is summarized in Table 2 (note that the reproductive structures mentioned are indicated in Figure 2A). The penial complex – comprising the preputium, penis, and retractor muscles – is innervated by peptidergic neurons of the right anterior lobe, ventral lobe, pedal Ib cluster, and dispersed neurons from the right pleural and parietal ganglia (e.g., Kemenes et al., 1989; Croll et al., 1991; Li et al., 1992). For example, conopressin and APGW co-localize in neurons innervating the penial complex and vas deferens (Van Kesteren et al., 1992; Van Golen et al., 1995a,b). Fibers containing FMRF and its co-expressed peptides (see above and Table 1) are found in the penial complex (Bright et al., 1993; Santama et al., 1993, 1995; Van Golen et al., 1995a,b) as well as several other substances (see Table 2). In addition, axons from the anterior lobe have also been found to innervate the pedal Ib cluster directly (Croll et al., 1991; Croll and Van Minnen, 1992).

Table 2.

Pattern of innervation by fibers containing the different transmitters involved in male reproduction of hermaphroditic freshwater snails.

| Transmitter | innervation pattern | References | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| np | PRM | PP | PE | VD | pace. | PG | SD | HD | SV | OO | ||

| APGW | + | + | + | + | + | + | Van Golen et al. (1995a,b); Van Kesteren et al. (1992); De Lange et al. (1998a) | |||||

| Conopressin | + | + | + | + | + | Van Golen et al. (1995a,b); Van Kesteren et al. (1992) | ||||||

| C-terminally located anterior lobe peptide (CALP) | ||||||||||||

| DEILSR | + | + | De Lange et al. (1998a) | |||||||||

| EFLRI | + | + | + | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a,b) | ||||||||

| FLRF | + | + | + | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a,b) | ||||||||

| FMRF | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Schott and Boer (1982); Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a,b); De Lange et al. (1997, 1998a) | ||||

| FVRIs | + | + | + | El Filali et al. (2006) | ||||||||

| G/SDPFLRF | ||||||||||||

| Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) | + | Young et al. (1999) | ||||||||||

| Lymnaea inhibitory peptides (LIP A, B, C) | + | + | + | + | + | + | Smit et al. (2003); De Lange et al. (1998a) | |||||

| Lymnaea neuopeptide Y (LyNPY) | + | + | De Lange et al. (1997) | |||||||||

| Myomodulins | + | + | Li et al. (1994a,b) | |||||||||

| Pedal peptide (PP) | + | De Lange et al. (1998a) | ||||||||||

| pQFYRI | + | + | + | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a,b) | ||||||||

| SEEPLY | + | + | + | Bright et al. (1993); Santama et al. (1993, 1995); Van Golen et al. (1995a,b); De Lange et al. (1998a) | ||||||||

| Serotonin (5HT) | + | + | + | Croll and Chiasson (1989) | ||||||||

HD, hermaphroditic duct; np, nervus penis; OO, oothecal gland; pace, pacemaker area of vas deferens; PE, penis; PG, prostate gland; PP, preputium; PRM, preputial retractor muscle; SD, sperm duct; SV, seminal vesicles; VD, vas deferens. Locations with a plus (+) indicate that nerve fibers containing thetransmitter have been detected

Neuro-endocrinology of male behavior

Behavior in the male role in Basommatophora is typically composed of a series of courtship events (shell mounting, circling, positioning, preputial eversion, probing) and typically ends in a unilateral copulation (penis eversion and intromission) (Figure 2B). The neuro-endocrinology of this behavioral sequence has been worked out in detail in L. stagnalis and will be reviewed in the following, largely based on the behavioral descriptions of Van Duivenboden and Ter Maat (1985), De Boer et al. (1996), and the review by De Lange et al. (1998a).

Figure 2.

Reproductive morphology and behavior of Lymnaea stagnalis. (A) General morphology of reproductive system and gamete movement. Schematic representation of the reproductive morphology. The blue dotted lines and arrows indicate the route that the snail's own sperm (autosperm) take after they are produced for storage (in the SV) and subsequently transfer to a partner. The red dotted lines and arrows indicate the fate of received sperm (allosperm) within the female tract. All the organs are indicated with capital letters. The different components of the egg mass are indicated in small letters, and their origin is indicated with an black arrow. The red solid lines indicate the course of the eggs during packaging in the female tract. AD, allosperm duct; AG, albumen gland; BC, bursa copulatrix; C, carrefour/fertilization pouch; fert., fertilization; HD, hermaphroditic duct; M, muciparous gland; me, membrana externa; mi, membrana interna; o, oocyte; O, oothecal gland; OT, ovotestis; P, penis; PCO, pars contorta; PE, preputium; pf, perivitellin fluid; PG, prostate gland; SD, sperm duct; sf, seminal fluid; SV, seminal vesicles; tc, tunica capsulis; ti, tunica interna; V, vaginal duct; VD, vas deferens. (B) Copulation behavior. The drawings show the different stages of male courtship and insemination behavior. Copulation starts with mounting (1) on the shell. For some 5 min, the sperm donor then performs counterclockwise circling (2), first toward the shell's tip and then toward its margin. It then takes on average 17 min from positioning (3) to intromission (4), during which eversion of and probing (5) with the preputium occur. Once intromission (6) is reached, an average insemination takes 35 min. The sperm donor is displayed in black, the sperm recipient in gray. (C) Egg-laying behavior. The drawings show the different stages of female reproductive behavior, i.e., egg laying. The behavior is redrawn from Ter Maat et al. (1987). Egg laying starts with a resting phase (1) of on average 40 min, during which locomotion stops, the shell is held still and slightly pulled forward over the tentacles and no rasping occurs. During the turning phase (2), lasting around 60 min, locomoting starts again, the shell is turned back and forth by 90° and the surface is rasped. Oviposition (3) usually lasts about 10 min during which the animal continues rasping, but stops shell turning and hardly moves. During inspection (4) the animal crawls along the mass for up to 30 min without rasping or shell turning. The panels are adapted from Jarne et al. (2010).

Eversion of the preputium

Following circling and positioning on the shell, once the animal has found the right position, the partially everted preputium becomes visible as a white bulge behind the right tentacle (and, evidently, the left tentacle in sinistral species) (Figure 2B). Eversion of the preputium requires the relaxation of the circular muscles surrounding the male gonopore as well as the preputium retractor muscle bands. Using immunocytochemistry, many of the abovementioned neuropeptides have been found around the male gonopore and in the preputial muscles (see Table 2). Table 3 illustrates that many of these affect contractions of the preputium retractor muscle bands in vitro. Importantly, injection of APGW into the blood causes penial eversion in vivo (De Boer et al., 1997a,b). Although in B. glabrata, application of APGW into the water did not cause eversion, FMRF did (Muschamp and Fong, 2001; Fong et al., 2005). In addition, the presence of selective serotonin-uptake inhibitors, like prozac, and serotonin-antagonists in the water caused eversion (Muschamp and Fong, 2001; Fong et al., 2005), corroborating that the classic transmitter serotonin itself may prevent eversion.

Hence, these substances clearly play a role in preputium eversion. The eversion has been suggested to be facilitated by the existing hydrostatic pressure in the head sinus or an increased pressure in the arteria penis (Bekius, 1972; see also De Boer et al., 2010). De Lange et al. (1998a) speculated that alternate contraction of longitudinal muscles inside and near the body wall and relaxation of circular preputium muscles near the body wall could also contribute to the subsequent full eversion of the preputium. They further suggested that these contractions and relaxations might be controlled by the ventral lobe, pleural, and parietal motor neurons (given the presence of substances affecting these muscles) and that the different locations of these neuro-endocrine substances within the preputium clearly allow for the very fine-tuned movements that are essential during probing (De Lange et al., 1998b).

Probing

During probing, the fully everted preputium makes movements under the lip of the shell (into the aperture) of the recipient in search of the female gonopore (De Boer et al., 1996). This presumably requires a sensory mechanism ensuring the correct position of the preputium prior to eversion and intromission of the penis. The most obvious candidates that could serve this function are the neurons that are found at the distal tip of the preputium. Several of these cells seem to be sensory neurons that contain conopressin, with a dendrite extending though the preputial epithelium and an axon in the penis nerve (respectively, Zijlstra, 1972; De Lange et al., 1998a), while others form varicosities on local musculature and contain containing APGW, pedal peptide, and/or LIP (De Lange et al., 1998a). The latter suggests that these neurons may also directly control the minor positional adjustments that are necessary for penis intromission (De Lange et al., 1998a).

Penis eversion and intromission

The end of these courtship behaviors and the start of copulation is marked by the intromission of the penis into the female gonopore. The position of nerve fibers containing different neuropeptides in the longitudinal and circular muscle layers of the penis suggests that alternate contraction of these muscle layers could result in the eversion of the penis (De Lange et al., 1998a). Like the preputium, the everted penis is probably also given support by blood pressure (in the arteria penis muscularis) (L. stagnalis: Bekius, 1972; B. glabrata: De Jong-Brink, 1969).

Transport of semen

Once intromission is achieved, sperm and seminal fluid are transferred into the vaginal duct of the recipient. Ripe sperm, produced in the ovotestis (De Jong-Brink et al., 1977; Rigby, 1982), are released from the seminal vesicles and transported via the sperm duct toward the prostate gland, where seminal fluid is added (Figure 2A). The semen is then transported to the penis via the vas deferens. The latter organ then shows rhythmic muscle contractions that travel over its whole length and presumably start in the so-called pacemaker area near the prostate gland (unpublished data in De Lange et al., 1998a). This peristalsis has been proposed to be caused by the antagonizing effects of APGW and conopressin on the vas deferens (see Table 3). This idea is supported by the resemblance of conopressin with vasopressin/oxytocin, which are involved in ejaculation in vertebrates (Van Kesteren et al., 1996). Additionally, the pacemaker area seems essential for peristalsis and its neurons contain LyNPY and receive input from the CNS via a branch of the nervus penis called np1 (and the contraction frequency can be changed via electrical stimulation of this nerve: unpublished data in De Lange et al., 1998a). Further down the vas deferens its muscles are innervated by axons containing APGW, LIP, or serotonin, but not conopressin. The prostate gland cells are surrounded by small muscle fibers, which are innervated by fibers containing APGW (Croll and Van Minnen, 1992) and DEILSR (the latter only in the area of the sperm duct, De Lange et al., 1998a).

Table 3.

Effects of the neuro-endocrine substances involved in male and female reproduction of hermaphroditic freshwater snails.

| Sex | Transmitter | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | APGW | Eversion of preputium | De Boer et al. (1997a,b) |

| Relaxation of preputium retractor muscles | Croll et al. (1991) | ||

| Inhibition of excitatory effect of conopressin | Van Golen et al. (1995a,b); Van Kesteren et al. (1995a,b,c, 1996) | ||

| Hyperpolarization of CDCs and LGCs | Croll et al. (1991) | ||

| Conopressin | Stimulation of vas deferens’ contractions | Van Golen et al. (1995a,b) | |

| Inhibition of CDC activity | Van Kesteren et al. (1995a,b,c) | ||

| C-terminally located Anterior Lobe Peptide (CALP) | Unknown | ||

| DEILSR | Unknown | ||

| EFLRI | Unknown | ||

| FLRF | Contraction of preputium retractor muscles | Van Golen et al. (1995a) | |

| FMRF | Eversion of preputium | Muschamp and Fong (2001); Fong et al. (2005) | |

| Contraction of preputium retractor muscles | Van Golen et al. (1995a) | ||

| Inhibition of CDC activity | Brussaard et al. (1990) | ||

| FVRIs | Inhibition of vas deferens’ contractions | El Filali et al. (2006) | |

| G/SDPFLRF | Relaxation of preputium retractor muscles | Van Golen et al. (1995a) | |

| Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) | Unknown | ||

| Lymnaea inhibitory peptides (LIP A, B, C) | Relaxation of preputium retractor muscles | Li et al. (1992) | |

| Reduction of amplitude of preputium retractor muscles contractions | Van Golen et al. (1995b); Smit et al. (2003) | ||

| Lymnaea neuropeptide Y (LyNPY) | Relaxation of preputium retractor muscles | Li et al. (1992) | |

| Inhibition of egg laying and reduction of growth | De Jong-Brink et al. (2001) | ||

| Myomodulins | Relaxation of preputium retractor muscles | Li et al. (1992) | |

| Modulation of amplitude of preputium retractor muscles contractions | Van Golen et al. (1996) | ||

| Pedal peptide (PP) | Unknown | ||

| pQFYRI | Unknown | ||

| SEEPLY | Unknown | ||

| Serotonin (5HT) | Contraction of preputium retractor muscles | Croll and Chiasson (1989); Croll et al. (1991); Li et al. (1992); Fong et al. (2005) | |

| Increase in egg laying | Manger et al. (1996) | ||

| Female | 1788Da: HF(FH)FYGPYDVFQRDV | Unknown | |

| 5895Da | Unknown | ||

| Amino terminal peptide (Nt) | Unknown | ||

| Calfluxin (CaFl) | Influx of Calcium into mitochondria of albumen gland | Dictus et al. (1987); | |

| Antagonized by schistosomin | De Jong-Brink et al. (1988a,b); Zhang et al (2009). | ||

| Carboxyl terminal peptide (CTP) | Unknown | ||

| Caudodorsal cell hormone (CDCH) | Initiation of ovulation (and thus egg laying behavior) | Ter Maat et al. (1986, 1989, 1987) | |

| Inhibition of right pedal motor neurons | Ter Maat et al. (1988) | ||

| (RPeN) | Ter Maat et al. (1988); Brussaard et al. (1990) | ||

| Local autoexcitation of CDCs | Wijdenes et al. (1983) | ||

| Stimulation of perivitellin fluid production | Jansen and Ter Maat (1985) | ||

| Inhibition of Ring neuron | |||

| Caudodorsal cell peptide α (α-CDCP) | Local autoexcitation of CDCs | Ter Maat et al. (1988); Brussaard et al. (1990) | |

| Excitation of motor neurons involved in shell movements and buccal rasping | Hermann et al. (1997) | ||

| Caudodorsal cell peptide β1 (β1-CDCP) | Unknown | ||

| Caudodorsal cell peptide β2 (β2-CDCP) | Unknown | ||

| Caudosorsal cell peptide β3 (β3-CDCP) | Excitation of motor neurons involved in locomotion, shell movements and buccal rasping | Hermann et al. (1997) | |

| Dorsal body hormone (DBH) | Inhibition of vitellogenesis | Geraerts and Joosse (1975) | |

| Stimulation of growth and development of female accessory sex organs | Geraerts and Joosse (1975); Geraerts and Algera (1976) | ||

| Stimulation of perivitellin fluid production | Wijdenes et al. (1983) | ||

| Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) | Unknown | ||

| LFRF | Inhibition of CDC and LGC activity | Hoek et al. (2005) | |

| γ-peptide | Unknown | ||

| δ-peptide | Unknown | ||

| ε-peptide | Unknown |

Penis and preputium retraction

Once ejaculation has finished the penis and preputium are retracted. The retraction of the penis is most likely regulated by relaxation of the aforementioned preputium muscles and a decrease in the hydrostatic pressure. For the much larger preputium, retraction seems to require the preputium retractor muscles, because when this set of muscles is cut these snails are incapable of retracting the organ (De Boer et al., 2010). The preputium retractor muscles are affected by many of the identified substances, as summarized in Table 3, and their effects are in concordance with the presence of nerve fibers containing these substances. Thus, many substances are involved in the contraction and relaxation of the preputium retractor muscles, which ultimately results in the eversion and retraction of the male copulatory organ. Evidently, some of these substances may also be involved in the fine coordination of preputial movement during courtship as well as copulation.

Male sexual drive

Hermaphroditic freshwater snails are not always motivated to mate in the male role, and sexual isolation is often used to increase mating activity for experiments (Van Duivenboden and Ter Maat, 1985; De Boer et al., 1997a,b). In L. stagnalis, male sexual drive increases when individuals have not mated for several days. If both individuals are motivated to mate as males, the individual that has been sexually isolated longest will act as male first; afterward, role alternation can take place so that both individuals get to mate in both roles sequentially (Van Duivenboden and Ter Maat, 1985; Koene and Ter Maat, 2005). The increase in size of the prostate gland, which produces the seminal fluid, is the permissive trigger motivating the animal to mate in the male role (De Boer et al., 1997a,b). Hence, this species only mates as a male when enough seminal fluid is present (Koene and Ter Maat, 2005). This increase in size of the prostate gland is detected in the CNS via a small branch of the penial nerve (np1, De Boer et al., 1997a,b). This sensory signal may be mediated by the neurons that have been found in the connective tissue surrounding the prostate gland (De Lange et al., 1998a).

Interestingly, cutting the np1 nerve allows for complete elimination of the male function (Van Duivenboden et al., 1985; De Visser et al., 1994; Koene et al., 2009a; Hoffer et al., submitted). The brain regions that receive and process the information from the prostate gland via np1 are the same ones known to control male reproductive behavior, and turn out to be evolutionarily conserved across molluscs (i.e., Basommatophora, Stylommatophora, and Opisthobranchia: Koene et al., 2000). However, whether the regulation of male motivation is also conserved and works similarly in other molluscs remains to be established.

An additional factor that seems important for male motivation is the identity of the partner. After copulating once in the male role, thus having partially depleted the prostate gland, individuals are able to inseminate again, but preferentially do so when the partner they encounter is novel (Koene and Ter Maat, 2007; but see Haederer et al., 2009). The latter is in accordance with predictions from sperm competition theory, as is the finding that more sperm are donated to virgin individuals (Loose and Koene, 2008). These aspects remain to be explored in other species of Basommatophora.

Female Reproductive Behavior and Its Neuro-Endocrine Control

In L. stagnalis, as illustrated in Figure 1A, the main neuroendocrine center for the control of female reproductive behavior is the bilateral caudo-dorsal cell (CDC) cluster situated in the cerebral ganglia, and its neurohemal area in the cerebral commissure. The dorsal bodies (Figure 1A) comprise a second bilateral endocrine organ that is important for female development and oogenesis. Cells that are morphologically similar to CDCs of L. stagnalis have been found in Stagnicola palustris, Radix ovata, B. truncatus, Planorbis planorbis, Planorbis vortex, Planorbarius corneus, and B. glabrata (Boer et al., 1977; Roubos and Van der Ven, 1987). Besides in L. stagnalis, dorsal bodies have also been found in P. corneus, B. glabrata, Ancylus flaviatilis, and B. truncatus (Lever et al., 1965; Boer et al., 1968; Boer et al., 1977). The following will first briefly describe the involved neurons and their endocrinology (Figure 1), and subsequently their involvement in the production of female behavior.

Central and peripheral neuro-endocrinology of female function

Caudo-dorsal cells

Egg laying is controlled by a bilateral group of neurons in the cerebral ganglia, the CDCs (Figure 1A), which can each be divided into a ventral and dorsal cluster (Ter Maat et al., 1983a). The importance of the CDCs was first revealed by cauterizing these cells, which completely abolished egg laying (Geraerts and Bohlken, 1976). These cells project into the neurohemal area of the cerebral commissure, are electrically coupled, and send axons through the cerebral commissure to the contralateral cell cluster (Joosse, 1964; Wendelaar-Bonga, 1971; Roubos, 1976; De Vlieger et al., 1980). As a result, these cells show a synchronous, long-lasting discharge both in vitro and in vivo (respectively, De Vlieger et al., 1980; Ter Maat et al., 1986). That these CDCs are neurosecretory and that their products induce egg laying was first shown by injecting extracts from the cerebral commissure (e.g., Geraerts and Bohlken, 1976). This also works in different Lymnaeidae, although cross-species tests show that there is family specificity (comparing Lymnaea, Bulinus, Biomphalaria: Dogterom and Van Loenhout, 1983).

The confirmation that the CDCs release hormones into the blood during their bursting activity comes from a very elegant in vitro experiment by Ter Maat et al. (1988). In this experiment the CDCs in one central nervous system preparation were induced to discharge. The reaction in a second preparation, that was placed adjacent in the same saline bath, was recorded and revealed that these CDCs also started a long-lasting discharge. This convincingly demonstrated that the initiation of this activity is chemically mediated. It turns out that several peptides are involved and released into the blood (e.g., Geraerts et al., 1983, 1985; Geraerts and Hogenes, 1985). The different peptides that have so far been identified are listed in Table 1 and most are encoded on the same gene (Figure 1B). Two of the three identified copies of the gene, called CDCH-I and -II, code for these 11 peptides (Hermann et al., 1997) and are both expressed in the CDCs (Van Minnen et al., 1989a,b). Moreover, CDCH-I is found in neurons throughout the female tract except the albumen gland (Van Minnen et al., 1989a,b). CDCH-I and -II are also found in nerve fibers in the prostate gland, while CDCH-I-positive secretions are found in the secretory cells of the sperm duct and semen and only CDCH-II-positive fibers in the preputium (Van Minnen et al., 1989a,b). α-CDCP has also been reported in B. glabrata (Van Minnen et al., 1992). The key peptide for egg laying seems to be CDCH, because the injection of this hormone alone triggers egg laying (Ter Maat et al., 1987). The identified functions of a number of the other involved peptides are described below (see also Table 3).

Dorsal bodies

The surgical removal of the dorsal bodies results in no egg production in juveniles and low egg production in adult. Moreover, vitellogenesis is blocked in the ovotestis, while spermatogenesis seems to continue normally (Geraerts and Joosse, 1975). The fact that the female function can be recovered by implantation of dorsal bodies indicates that a hormonal factor, referred to as dorsal body hormone is involved (Geraerts and Joosse, 1975), but its molecular identity remains elusive. This hormone is probably produced in the single type of endocrine cells that the organ is composed of (Joosse, 1964; Wijdenes et al., 1983). This dorsal body hormone also stimulates growth and development of female accessory sex organs, while it does not affect male accessory organs (Geraerts and Joosse, 1975; Geraerts and Algera, 1976).

Neuro-endocrinology of female behavior

Most Basommatophora lay their eggs in egg masses that they fix to the substrate (Figure 2C). A number of the behavioral components described below are found in several basommatophoran species (e.g., L. stagnalis: Ter Maat et al., 1987; Bulinus octoploides: Rudolph and White, 1979; A. flaviatilis: Bondesen, 1950a,b). But because egg-laying behavior and its underlying mechanisms, have been studied in great detail in L. stagnalis, the description below mostly focuses on this species and is based on the detailed descriptions of Goldschmeding et al. (1983) and Ferguson et al. (1993), plus the overview of the sequence of egg-laying events provided by Hermann et al. (1997).

Resting phase

The abovementioned CDC discharge triggers the start of egg laying, the resting phase. During this discharge the CDCs release all peptides encoded on the CDCH-gene (Ferguson et al., 1993; also Jansen and Ter Maat, 1985). The resting phase lasts on average 40 min during which the animal stops locomotion, holds its shell still and slightly pulled forward over the tentacles and does not rasp the substrate. The egg laying hormone CDCH inhibits the right pedal motor neurons (RPeN), which is probably the reason why locomotion does not take place. Both α-CDCP (previously called CDCA) and CDCH act as local autoexcitatory transmitters on the CDCs and thus spread the excitation from the CDCs that receive external input over the entire CDC network (Ter Maat et al., 1988). This positive feedback makes both CDCH and α-CDCP, but not the β-CDCPs, necessary for the CDC discharge and generates an all-or-none response (Ter Maat et al., 1988; Brussaard et al., 1990). CDCH also initiates the actual ovulation, which is followed by the fertilization and packaging of the released ripe eggs by the female accessory glands (Figure 2A).

Turning phase

The passing of eggs through the tract is sensed by ciliated cells that send nervous signals to the central nervous system via the intestinal nerve. This signal triggers the release of β3-CDCP and α-CDCP, from other cells than the CDCs, at which point the animal enters the turning phase. This phase lasts around 60 min during which the animal starts locomoting again, turns its shell back and forth by 90° and rasps the surface. Locomotion is probably initiated by the increased activity of RPeN motor neurons induced by CDCH and β3-CDCP, and possible also via direct axonal projections from the CDCs (Hermann et al., 1997). β3- and α-CDCP also excite other motor neurons that are involved in shell movements and buccal rasping (Hermann et al., 1997). Some of these motor neurons project into the inferior cervical nerves that control the columellar muscle, and bilateral lesioning of these nerves eliminates shell turning during egg laying (Hermann et al., 1994). Buccal rasping is performed to clean the substrate for proper attachment of the egg mass (Ter Maat et al., 1989). This process continues as long as the passage of eggs through the female tract is registered, which explains the clear correlation between the duration of the turning phase, as well as the following oviposition, with the size of the egg mass (Ter Maat et al., 1987, 1989; Ferguson et al., 1993). In turn, the number of eggs in an egg mass depends on the time since last oviposition, indicating that ripe oocytes accumulate in the ovotestis (Ter Maat et al., 1983a; see also Koene et al., 2006) and explaining why egg mass size is independent of the injected dose of CDCH (Dogterom et al., 1983).

Oviposition and inspection phase

Oviposition starts when the egg mass emerges from the female gonopore and is fixed to the substrate. This phase usually lasts about 10 min during which the animal continues rasping, stops shell turning and hardly locomotes. When the egg mass has been deposited, the animal crawls along the mass, without rasping or shell turning, before leaving it behind; this is referred to the inspection phase and can last up to 30 min.

Egg mass production

Several stages can be distinguished in oogenesis (e.g., De Jong-Brink and Geraerts, 1982). The oogonia are first apposed and then enveloped by follicle cells. Next the developing oocyte forms clefts with the follicle cell, after which the oocyte matures into a ripe oocyte. When egg laying starts, ripe oocytes are ovulated from the ovotestis and fertilized in the fertilization pouch. Subsequently, the albumen gland supplies each egg with perivitelline fluid, which is galactogen-rich (Plesch et al., 1971; Wijsman, 1989). Each egg is then enveloped in two membranes, the membrana interna and externa, that are secreted by the posterior and anterior part of the pars contorta. The muciparous gland secretes a mucus that fuses the eggs together, the tunica interna, after which the tunica capsulis surrounds the whole egg mass in the oothecal gland (Plesch et al., 1971). The egg mass is then deposited via the female gonopore and stuck to the substrate. The pallium gelatinosum aids in sticking the mass to the substrate, and may be secreted by the glandular cells found in the gonopore (Plesch et al., 1971). This process is summarized in Figure 2A.

Adult L. stagnalis can lay egg masses at a frequency of at least one mass per week, and such masses contain on average between 50 and 150 eggs depending on the individual's body size (Koene et al., 2007). This species seems to have a preference for laying eggs during the day (Ter Maat et al., unpublished), but other species have been found to predominantly lay eggs during the night (P. corneus and H. trivolvis: Cole, 1925). The number of eggs in an egg mass and the laying frequency also vary widely for other species (Bondesen, 1950a,b; Dogterom and Van Loenhout, 1983). L. stagnalis that are older than 300 days usually show a decline in egg production (Janse et al., 1990; see also Hermann et al., 2009). Other factors that inhibit egg laying are starvation and dirty water (Ter Maat et al., 1982; Dogterom et al., 1984). As a consequence of the latter, egg laying can be triggered by a transfer from dirty to clean water. Although this is known as the clean water stimulus, the effect is actually caused by a combination of clean water, clean surface and higher oxygen (Ter Maat et al., 1983a).

Spiking activity of the CDCs is not affected by dirty water (Ter Maat et al., 1982). However, during starvation the CDCs become hyperpolarized, which elevates the threshold for egg laying (Ter Maat et al., 1982). CDC spiking can also be arrested by dopaminergic neuronal input from most nerves tested (Ter Maat, 1979; Ter Maat and Lodder, 1980). One important nerve is the intestinal nerve, which transmits information from the female reproductive tract, via the pleuroparietal connective, to the cerebral ganglia (Ferguson et al., 1993). The RPeNs also receive input from the intestinal nerve (Hermann et al., 1997). Lesioning this nerve results in decreased rasping and shell turning during egg laying (Ferguson et al., 1993), but eliminates neither the excitatory effects of α-CDCP and β3-CDCP on shell movements and rasping rate nor their inhibitory effect on locomotion (Hermann et al., 1997). The CDCs also have a refractory period, they are inhibited for up to 4 h after egg laying, and then return to their normal resting state from which they can enter the active state again (Kits, 1980). This inactivity may be correlated with the depletion of secretory products in the commissure after egg laying. These products are replenished in the hours following egg laying with the reserve pool of product that is present in the cell bodies of the CDCs (Jiménez et al., 2004).

Female sexual drive

The ability to self-fertilize is common within this group although the tendency to favor outcrossing over selfing seems to vary widely between species and families (Escobar et al., submitted). L. stagnalis, for instance, has a strong preference for outcrossing (Cain, 1956; Knott et al., 2003; Koene et al., 2009b). As mentioned earlier, most freshwater pulmonates can mate in the male and female role, but within a copulation each individual only performs one sexual role. Generally, it is assumed that these snails are usually receptive as females, because they seem rather inactive when copulating in this role (Van Duivenboden and Ter Maat, 1985). However, evidence from Physa indicates that recipients have several behaviors at their disposal that could discourage insemination (DeWitt, 1996; Wethington and Dillon, 1996). For instance, by using shell swinging and phallus biting the individuals being mounted can discourage certain partners from inseminating them (Facon et al., 2006). Such female behaviors remain to be explored for other species.

Coordination of Male and Female Behavior

Inhibiting the opposite sexual function

Evidently, the hermaphroditic lifestyle of these animals requires a strict coordination of the two sexual functions in such a way that they will not be performed simultaneously. Thus, when the male role is performed, the female role needs to be suppressed, and vice versa. Indeed, some of the substances that are released during the performance of male behavior or egg laying seem to prevent the expression of the opposite sexual function. For example, APGW, which plays a key role in the control of male copulatory behavior, hyperpolarizes the CDCs in L. stagnalis thus inhibiting the CDC afterdischarge that is necessary for the release of CDCH and initiation of egg laying (Croll et al., 1991). FMRF also inhibits activity of the CDCs (Brussaard et al., 1990) and its presence arrests ongoing firing and prevents initiation of new discharges (Brussaard et al., 1988; Croll et al., 1991). Further substances that have been reported to inhibit the CDCs, egg laying and growth are summarized in Table 3.

Both APGW and LFRFs hyperpolarize the insulin-like hormone producing Light Green Cells, which normally stimulate growth (Croll et al., 1991; Hoek et al., 2005; schistosomin excites these cells: Hordijk et al., 1991a,b, 1992). This could explain the observed reduction in growth as a result of more mating opportunities (Koene and Ter Maat, 2004; Koene et al., 2006), although it is also possible that such a reallocation of energy is triggered by a substance transferred in the semen (Koene et al., 2006, 2009a, 2010).

Interesting to note in this context is the recently-discovered peptide from the prostate gland in L. stagnalis which seems to influence egg laying. The prostate gland produces the seminal fluid that is added to the sperm prior to transfer to the partner. The identified seminal fluid peptide, referred to as Ovipostatin, suppresses egg laying in the recipient (Koene et al., 2010). Since hermaphrodites express genes for male and female reproductive pathways, in principle active compounds for partner manipulation are immediately available and only require appropriate means for delivery (Koene, 2005; Bedhomme et al., 2009). This would strongly suggest that such allohormones may evolve more easily in hermaphrodites, in comparison with separate sex species, and may initially resemble already existing regulatory peptides.

Finally, one candidate transmitter that can inhibit the male behavior when eggs are being laid is serotonin. In B. glabrata serotonin has been shown to increase egg laying (Manger et al., 1996), while a serotonin-antagonist (Methiothepin) reduces egg laying and everts the penis (Muschamp and Fong, 2001). The latter is in agreement with the finding that serotonin normally contracts the preputium retractor muscle, thus preventing eversion.

Ring neuron

All the abovementioned inhibitions of components of either sexual function (and growth) occur during the performance of the opposite sexual role, because this is when these substances are released and/or circulate in the hemolymph. However, there is also some evidence that there might be actual coordinating “centers” that can regulate the activity of the neurons responsible for male and female behavior. One such neuron is the ring neuron, which is an unpaired neuron situated in the right cerebral ganglion (Ter Maat and Jansen, 1984). The ring neuron contains APGW (Croll and Van Minnen, 1992) and receives EPSPs when the penial nerve is stimulated (Ter Maat and Jansen, 1984; Jansen et al., 1985). This neuron also has an inhibitory input on the ventrally located CDCs (Jansen et al., 1985), while it is excited by CDC discharge and activity and inhibited by CDCH (Jansen and Bos, 1984; Ter Maat and Jansen, 1984; Jansen and Ter Maat, 1985). The initial excitation of the ring neuron by CDC activity results in an inhibition of the pedal neurons, and may thus be responsible for the resting phase (Jansen and Ter Maat, 1985). When enough CDCH has been released the ring neuron gets inhibited, which would coincide with the transition from the resting to the turning phase (Ter Maat et al., 1987). This is in accordance with the finding that the ring neuron also modulates the columellar muscle, which controls shell turning during egg laying (and shell movement in general, Jansen and Ter Maat, 1985). Thus, given the involvement of this interneuron in both male and female components of the reproductive behavior, it is so far the best candidate to regulate the behavioral switch between the male and female function of this hermaphrodite (see also Ter Maat and Jansen, 1984).

Lateral lobes

An explanation for why some of the substances also have an effect on growth might be sought in the lateral lobes. The lateral lobes are a bilateral endocrine organ attached to the cerebral ganglia (Geraerts, 1976). These rather small lobes are composed of three types of neurosecretory cells plus follicle cells (Geraerts, 1976). These B cells, canopy cells, droplet cells and follicle cells, have been found in a number of freshwater snails (L. stagnalis, Ancylus fluviatilis, P. corneus: Brink and Boer, 1967; Helisoma duryi: Saleuddin and Ashton, 1996; B. truncatus: Boer et al., 1977; B. glabrata: Lever et al., 1965). The only known factors that are present in the lateral lobes are the LFRFs (Hoek et al., 2005) and GnRH (Young et al., 1999).

In L. stagnalis cauterization and reimplantation experiments have shown that the lateral lobes are endocrine organs (Geraerts, 1976). When they are absent spermatogenesis and spermiation decelerate, which results in male maturation being delayed by approximately 20 days. Likewise the reduction in oocyte maturation, ovulation, dorsal body development, and maturation of female accessory organs results in female maturation being delayed by approximately 10 days. The presence of the lateral lobes stimulates the rate of oogenesis while it reduces body growth (these two processes are known to be inversely related, e.g., Koene and Ter Maat, 2004). The increased body growth in the absence of the lateral lobes becomes both apparent in the production of thinner shells and lower body wet weights (Geraerts, 1976). In B. truncatus cauterization of the lateral lobes also increases growth and reduces oviposition (Mohamed and Geraerts, 1980). The absence of the lateral lobes seems to stimulate the release of hormone by the light green cells and inhibit both the release of CDCH by the CDCs and the endocrine activity of the dorsal bodies (Roubos et al., 1980). That the effect on body size acts via the growth hormone producing light green cells is confirmed by the finding that the effect disappears when both the lateral lobes and light green cells were surgically removed (Geraerts, 1976). Cells morphologically similar to light green cells have also been reported in S. palustris, R. ovata, B. truncatus, P. planorbis, Planorbis vortex, P. corneus, and B. glabrata (Roubos and Van der Ven, 1987).

Mating decisions

The foregoing has already illustrated that there are several internal and external factors that may influence the sexual drive to perform the male or female role, and that these decisions may be interlinked. A point in case is role alternation, i.e., the swapping of sexual roles after a first mating interaction which results in each partner performing both sexual roles in sequence. For L. stagnalis it has been demonstrated that such role alternations predominantly occur when both individuals are motivated to mate in the male role (Koene and Ter Maat, 2005). First, this illustrates that after copulation the opposite mating role can be performed immediately. Second, given that male sexual drive regulates this alternation of roles, this indicates that partners do not induce each other to swap roles (for example via a seminal fluid substance; Koene and Ter Maat, 2005). In addition, remating in the female role seems not to be inhibited after insemination, given that sperm recipients can be inseminated several times in a row by different partners (Koene and Ter Maat, 2007; Koene et al., 2009a). Thus, the prediction that emerges from all this is that when the male role is performed this generally takes precedence over the female role in these hermaphrodites, which seems to match the current theoretical framework (Anthes et al., 2006).

Recent experiments have shown that pond snails can distinguish novel from familiar partners (Koene and Ter Maat, 2007) and adjust sperm transfer depending on the partner's mating history (Loose and Koene, 2008). So far, the evidence seems to suggest that these animals use cues in the mucus trail to detect the mating history of a partner and transfer sperm accordingly (Koene and Ter Maat, 2007). Besides the ability to detect such biochemicals, this also indicates that such chemical cues differ between individuals in different reproductive states.

The neural mechanism for such mating decisions is most likely mediated via the lips, which have been identified as the primary chemosensory organ in L. stagnalis. The lips have a variety of sensory cells and nerve endings (Zijlstra, 1972; Zaitseva and Bocharova, 1981) and are innervated by the left and right median lip nerves, which form an extensive network of nerve endings (Nakamura et al., 1999a). Lesion studies have shown that the excitatory effect of sucrose on feeding movements of the buccal mass reaches the central nervous system through these nerves (e.g., Goldschmeding and Jager, 1973). In addition, the central pattern generator underlying feeding is studied using semi-intact preparations consisting of the lips, central nervous system, and buccal system (e.g., Nakamura et al., 1999b; Straub et al., 2004). Similar approaches, i.e., lesion studies and semi-intact preparations, could now be used to investigate whether the lips detect factors in the mucus and/or water that are indicative of mating history. Such studies should then be followed up by further electrophysiological experiments in combination with retrograde nerve staining, to identify the central neurons that receive this information. Such neurons would be the first candidates for involvement in mate choice, and their links with the known neural circuits of male and female reproduction are then clearly essential to uncover.

Such chemosensory information may also be used for differential semen allocation, i.e., donating different amounts of sperm and/or seminal fluid depending on fertilization opportunities and/or the partner's mating history. Clearly, this requires that the biochemical information detected by the lips is somehow relayed to the organs that are involved in semen transfer. For the prostate gland (seminal fluid) such information is predicted to run through the np1 branch of the nervus penis (De Boer et al., 1997a,b), while for the seminal vesicles and ovotestis (sperm) this would be the intestinal nerve (Elo, 1938). Understanding the underlying mechanisms will be extremely valuable for a proper understanding of mating decisions made by these hermaphrodites.

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Molluscs are still used extensively as model species for neuro-endocrine processes that regulate different types of behaviors. Clearly, for the regulation of reproductive behaviors much of the knowledge is based on research performed with the simultaneously hermaphroditic freshwater snail L. stagnalis. Therefore, the initiatives to gather large-scale genomic and transcriptomic data for this species (Davison and Blaxter, 2005; Feng et al., 2009) are extremely valuable and are expected to further deepen our knowledge about the intricacies of regulatory processes in these animals. In addition to focusing on this model species, it would now be very informative to know to which extent the gathered knowledge about these neuro-endocrine processes can be extended to other basommatophoran (non-)model species.

Next to such mechanistic studies, a large body of research at the ecological and evolutionary level has developed on this pond snail and many related freshwater snails (reviewed in Jarne et al., 2010). At each of these biological levels, much of the research has focused on reproductive processes and behaviors. However, there has been a surprising lack of integration between these different fields of research, although this would clearly be beneficial for both sides (e.g., Koene et al., 2009b). For example, knowledge about the underlying neuro-endocrine mechanisms regulating male and female reproductive behaviors is extremely useful for fields of research concerned with sexual selection (e.g., Koene et al., 2009a) and endocrine disruption (e.g., Lagadic et al., 2007), which focus on various aspects of reproductive output of these hermaphrodites. So far the overlapping interest between these fields of research has not been fully exploited, while at such an interface between disciplines the resulting integration is expected to lead to novel insights and major advances. For example, knowing which of the reviewed neuro-endocrine processes are highly conserved and which ones widely diverge will be extremely informative for understanding the evolution of this hermaphroditic mode of reproduction.

One further area of particular interest at this interface is the coordination of expression of male and female behaviors within these hermaphrodites. The very detailed understanding of both male and female reproductive function in pond snails provides an excellent springboard for future research into how simultaneous hermaphrodites coordinate the dual nature of their sexual function, and some starting points are highlighted above. In itself, looking for such a “switch” between male and female function is a very promising anenue of research that needs to be properly addressed. In addition, besides answering such proximate questions, uncovering such a mechanism is expected to also shed light on evolutionary aspects of hermaphroditism within this group of animals as well as in general. For instance, if such a “switch” can be exploited by the sperm donor to influence the recipient's investment patterns, this will clearly provide a link between the mechanistic basis of the coordination of reproduction via either sexual roles and the evolutionary implications that this can have in terms of sexual selection and sexual conflict (Koene, 2005; Bedhomme et al., 2009; Koene et al., 2009a).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This review has benefited from input from and discussions with Andries ter Maat, Jeroen N.A. Hoffer, Zineb El Filali, Lukas Schärer, Kurt Jordaens, Nils Anthes, Benjamin Pélissié, Philippe Jarne, and Patrice David as well as the two referees. JMK's research is funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) as well as a Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel Research Award of the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation.

References

- Anthes N., Putz A., Michiels N. K. (2006). Sex role preferences, gender conflict and sperm trading in simultaneous hermaphrodites: a new framework. Anim. Behav. 72, 1–12 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.09.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedhomme S., Bernasconi G., Koene J. M., Lankinen Å., Arathi S., Michiels N. K., Anthes N. (2009). How does breeding system variation modulate sexual antagonism? Biol Lett. 5, 717–720 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekius R. (1972). The circulatory system of Lymnaea stagnalis L. Neth J. Zool. 22, 1–58 10.1163/002829672X00176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boer H. H., Roubos E. W., Van Dalen H., Groesbeek J. R. F., Th. (1977). Neurosecretion in the basommatophoran snail Bulinus truncatus (Gastropoda, Pulmonata). Cell Tissue Res. 176, 57–67 10.1007/BF00220344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer H. H., Slot J. W., Van Andel J. (1968). Electron microscopical and histochemical observations on the relation between medio-dorsal bodies and neurosecretory cells in the basommatophoran snails Lymnaea stagnalis, Ancylus fluviatilis, Australorbis glabratus and Planorbarius corneus. Z. Zellforsch. 87, 435–450 10.1007/BF00333693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondesen P. (1950a). Egg capsules of river limpet snails: material for experimental biology. Science 2, 603–605 10.1126/science.111.2892.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondesen P. (1950b). A comparative morphological-biological analyses of the eggcapsules of freshwater pulmonate gastropods. Nat. Jutlandica. Aarhus 3, 1–208 [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J. P., Yoshino T. P. (2000). The effect of water quality on oviposition in Biomphalaria glabrata (Say, 1818) (Planorbidae), and a description of the stages of the egg-laying process. J. Mollus Stud. 66, 83–93 10.1093/mollus/66.1.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bright K., Kellett E., Saunders S. E., Brierley M., Burke J. F., Benjamin P. R. (1993). Mutually exclusive expression of alternatively spliced FMRFamide transcripts in identified neuronal systems of the snail Lymnaea. J. Neurosci. 13, 2719–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink M., Boer H. H. (1967). An electron microscopical investigation of the follicle gland (cerebral gland) and of some neurosecretory cells in the lateral lobe of the cerebral ganglion of the pulmonate gastropod Lymnaea stagnalis L. Cell Tissue Res. 79, 230–243 10.1007/BF00369287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumpt E. (1941). Observations biologiques diverses concernant Planorbis (Australorbis) glabratus hôte intermédiaire de Schistosoma mansoni. Ann. Parasitol. 18, 9–45 [Google Scholar]

- Brussaard A. B., Kits K. S., Ter Maat A., Van Minnen J., Moed P. J. (1988). Dual inhibitory action of FMRFamide on neurosecretory cells controlling egg laying behavior in the pond snail. Brain Res. 447, 35–51 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90963-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussaard A. B., Schluter N. C. M., Ebberink R. H. M., Kits K. S., Ter Maat A. (1990). Discharge induction in molluscan peptidergic cells requires a specific set of four autoexcitatory neuropeptides. Neuroscience 39, 479–491 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90284-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain G. L. (1956). Studies on cross-fertilization and self-fertilization in Lymnaea stagnalis appressa Say. Biol. Bull. 111, 45–52 10.2307/1539182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chase R. (2007). Gastropod reproductive behavior. Scholarpedia 2, 4125. 10.4249/scholarpedia.4125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole W. H. (1925). Egg laying in two species of Planorbis. Am. Nat. 59, 284–286 10.1086/280041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croll R. P., Chiasson B. J. (1989). Postembryonic development of serotoninlike immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Comp. Neurol. 280, 122–142 10.1002/cne.902800109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll R. P., Van Minnen J. (1992). Distribution of the peptide Ala-Pro-Gly-Trp-NH2 (APGWamide) in the nervous system and periphery of the snail Lymnaea stagnalis as revealed by immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. J. Comp. Neurol. 324, 567–574 10.1002/cne.903240409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll R. P., Van Minnen J., Kits K. S., Smit A. B. (1991). “APGWamide: molecular, histological and physiological examination of the novel neuropeptide involved with reproduction in the snail Lymnaea stagnalis,” in Molluscan Neurobiology, eds Kits K. S., Boer H. H., Joosse J. (North-Holland, Amsterdam; ), 248–254 [Google Scholar]

- Davison A., Barton N. H., Clarke B. (2009). The effect of coil phenotypes and genotypes on the fecundity and viability of Partula suturalis and Lymnaea stagnalis: implications for the evolution of sinistral snails. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 1624–1635 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison A., Blaxter M. L. (2005). An expressed sequence tag survey of gene expression in the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis, an intermediate vector of Fasciola hepatica. Parasitology 130, 539–552 10.1017/S0031182004006791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer P. A. C. M., Ter Maat A., Pieneman A. W., Croll R. P., Kurokawa M., Jansen R. F. (1997a). Functional role of peptidergic anterior lobe neurons in male sexual behavior of the snail Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Neurophysiol. 78, 2823–2833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer P. A. C. M., Jansen R. F., Koene J. M., Ter Maat A. (1997b). Nervous control of male sexual drive in the hermaphroditic snail Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 941–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer P. A. C. M., Jansen R. F., Ter Maat A. (1996). Copulation in the hermaphrodite snail Lymnaea stagnalis: a review. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 30, 167–176 [Google Scholar]

- De Boer P. A. C. M., Jansen R. F., Ter Maat A., Van Straalen N. M., Koene J. M. (2010). The distinction between retractor and protractor muscles of the freshwater snail's male organ has no physiological basis. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 40–44 10.1242/jeb.034371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong-Brink M. (1969). Histochemical and electron microscope observations on the reproductive tract of Biomphalaria glabrata (Australorbis glabratus), intermediate host of Schistosoma mansoni. Z. Zellforsch. 102, 507–542 10.1007/BF00335491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong-Brink M., Boer H. H., Hommes T. G., Kodde A. (1977). Spermatogenesis and the role of Sertoli cells in the freshwater snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Cell Tissue Res. 181, 37–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong-Brink M., Elsaadany M. M., Boer H. H. (1988a). Trichobilharzia ocellata: interference with endocrine control of female reproduction of Lymnaea stagnalis. Exp. Parasitol. 65, 91–100 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90110-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong-Brink M., Elsaadany M. M., Boer H. H. (1988b). Schistosomin, an antagonist of calfluxin. Exp. Parasitol. 65, 109–118 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90112-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong-Brink M., Geraerts W. P. M. (1982). Oogenesis in gastropods. Malacologia 22, 145–149 [Google Scholar]

- De Jong-Brink M., Tensen C. P., Ter Maat A. (2001). NPY in invertebrates: molecular answers to altered functions during evolution. Peptides 22, 309–315 10.1016/S0196-9781(01)00332-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lange R. P. J., Joosse J., Van Minnen J. (1998a). Multi-messenger innervation of the male sexual system of Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Comp. Neurol. 390, 564–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De jo Lange R. P. J., De Boer P. A. C. M., Ter Maat A., Tensen C. P., Van Minnen J. (1998b). Transmitter identification in neurons involved in male copulation behavior in Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Comp. Neurol. 395, 440–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lange R. P. J., Van Golen F. A., Van Minnen J. (1997). Diversity in cell specific co-expression of four neuropeptide genes involved in control of male copulation behaviour in Lymnaea stagnalis. Neuroscience 78, 289–299 10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00576-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lange R. P. J., Van Minnen J. (1998). Localization of the neuropeptide APGWamide in gastropod molluscs by in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 109, 166–174 10.1006/gcen.1997.7001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Visser J. A. G. M., Ter Maat A., Zonneveld C. (1994). Energy budgets and reproductive allocation in the simultaneous hermaphrodite pond snail, Lymnaea stagnalis (L): a trade-off between male and female function. Am. Nat. 144, 861–867 10.1086/285712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vlieger T. A., Kits K. S., Ter Maat A., Lodder J. C. (1980). Morphology and electrophysiology of the ovulation hormone producing neuro-endocrine cells of the freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis (L.). J. Exp. Biol. 84, 239–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt T. J. (1996). Gender contests in a simultaneous hermaphrodite snail: a size-advantage model for behaviour. Anim. Behav. 51, 345–351 10.1006/anbe.1996.0033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dictus W. J. A. G., De Jong-Brink M., Boer H. H. (1987). A neuropeptide (calfluxin) is involved in the influx of calcium into mitochondria of the albumen gland of the freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 65, 439–450 10.1016/0016-6480(87)90130-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogterom G. E., Bohlken S., Geraerts W. P. M. (1983). A rapid in vivo bioassay of the ovulation hormone of Lymnaea stagnalis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 50, 476–482 10.1016/0016-6480(83)90269-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogterom G. E., Van Loenhout H. (1983). Specificity of ovulation hormones of some basommatophoran species studied by means of iso- and heterospecific injections. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 52, 121–125 10.1016/0016-6480(83)90164-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogterom G. E., Van Loenhout H., Koomen W., Roubos E. W., Geraerts W. P. M. (1984). Ovulation hormone, nutritive state, and female reproductive activity in Lymnaea stagnalis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 55, 29–35 10.1016/0016-6480(84)90125-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C. J. (1975). “Reproduction,” in Pulmonates, Vol 1 eds Fretter V., Peake J. (London: Academic Press; ), 309–365 [Google Scholar]

- El Filali Z., Van Minnen J., Liu W. K., Smit A. B., Li K. W. (2006). Peptidomics analysis of neuropeptides involved in copulatory behavior of the mollusk Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Proteome Res. 5, 1611–1617 10.1021/pr060014p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elekes K., Hernádi L., Kemenes G. (1988). “Serotonin immunoreactive neurons in the CNS of helix and lymnaea,” in Neurobiology of Invertebrates, Transmitters, Modulators and Receptors, eds Salánki J., Rózsa K. S. (Budapest: Akademiai Kiad; ), 703–711 [Google Scholar]

- Elo J. E. (1938). Das nervensytem von Lymnaea stagnalis (L.). Lam. Ann. Zool. Vanamo 6, 1–40 [Google Scholar]

- Facon B., Ravigné V., Goudet J. (2006). Experimental evidence of inbreeding avoidance in the hermaphroditic snail Physa acuta. Evol. Ecol. 20, 395–406 10.1007/s10682-006-0009-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z.-P., Zhang Z., Van Kesteren R. E., Straub V. A., Van Nierop P., Jin K., Nejatbakhsh N., Goldberg J. I., Spencer G. E., Yeoman M. S., Wildering W., Coorssen J. R., Croll R. P., Buck L. T., Syed N. I., Smit A. B. (2009). Transcriptome analysis of the central nervous system of the mollusc Lymnaea stagnalis. BMC Genomics 10, 451. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson G. P., Pieneman A. W., Jansen R. F., Ter Maat A. (1993). Neuronal feedback in egg-laying behaviour of the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Exp. Biol. 178, 251–259 [Google Scholar]

- Fong P. P., Olex A. L., Farrell J. E., Majchrzak RM Muschamp J. W. (2005). Induction of preputium eversion by peptides, serotonin receptor antagonists, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in Biomphalaria glabrata. Invert. Biol. 124, 296–302 10.1111/j.1744-7410.2005.00027.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geraerts W. P. M. (1976). The control of ovulation in the hermaphroditic freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis by the neurohormone of the caudodorsal cells. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 28, 350–357 10.1016/0016-6480(76)90187-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraerts W. P. M., Algera L. H. (1976). The stimulating effect of the dorsal body hormone on cell differentiation in the female accessory sex organs of the hermaphrodite freshwater snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 29, 109–118 10.1016/0016-6480(76)90012-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraerts W. P. M., Bohlken S. (1976). The control of ovulation in the hermaphrodite freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis by the neurohormone of the caudo-dorsal cells. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 28, 350–357 10.1016/0016-6480(76)90187-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraerts W. P. M., Hogenes T. M. (1985). Heterogeneity of peptides released by electrically active neuroendocrine caudodorsal cells of Lymnaea stagnalis. Brain Res. 331, 51–61 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90714-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraerts W. P. M., Joosse J. (1975). Control of vitellogenesis and of growth of female accessory sex organs by the dorsal body hormone (DBH) in the hermaphroditic freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 27, 450–464 10.1016/0016-6480(75)90065-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraerts W. P. M., Tensen C., Hogenes T. H. M. (1983). Multiple release of peptides by electrically active neurosecretory caudo-dorsal cells of Lymnaea stagnalis. Neurosci. Lett. 41, 151–155 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90238-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]