Abstract

To achieve dosage balance of X-linked genes between mammalian males and females, one female X chromosome becomes inactivated. However, approximately 15% of genes on this inactivated chromosome escape X chromosome inactivation (XCI). Here, using a chromosome-wide analysis of primate X-linked orthologs, we test a hypothesis that such genes evolve under a unique selective pressure. We find that escape genes are subject to stronger purifying selection than inactivated genes and that positive selection does not significantly affect the evolution of these genes. The strength of selection does not differ between escape genes with similar versus different expression levels in males versus females. Intriguingly, escape genes possessing Y homologs evolve under the strongest purifying selection. We also found evidence of stronger conservation in gene expression levels in escape than inactivated genes. We hypothesize that divergence in function and expression between X and Y gametologs is driving such strong purifying selection for escape genes.

Keywords: purifying selection, dosage compensation, X chromosome inactivation

The genomes of therian mammals possess two sex chromosomes—X and Y (with XX females and XY males). To achieve dosage balance between males and females, one female X chromosome is inactivated (Payer and Lee 2008). However, not all genes on the inactive X become silenced. A comprehensive profile of the human inactive X (Carrel and Willard 2005) revealed that 75% of genes are inactivated in all females (inactivated genes), 15% of genes escape inactivation in all females (escape genes), and 10% of genes escape inactivation in some females (heterogeneous genes).

Selection may operate differently on escape than inactivated or heterogeneous genes. For instance, compared with 46,XX individuals, Turner syndrome individuals (45,X) lack biallelically expressed X-linked genes and exhibit distinct phenotypes including premature ovarian failure and short stature (Good et al. 2003; Bondy 2006). This observation suggests importance of function and of precise gene dosage of escape genes. Most X-linked genes with Y homologs escape XCI (Ross et al. 2005), which may serve to achieve dosage compensation between males and females. Relatedly, many mammalian X and Y homologs differ substantially in function and expression (Wilson and Makova 2009). Selection may act differently on escape genes with versus without Y homologs as most candidate Turner syndrome X-linked genes have Y homologs (Burgoyne 1989; Fisher et al. 1990; Ellison et al. 1997; Rao et al. 1997).

Distinct expression levels of escape genes between male and female brain (Skuse 2005; Xu and Disteche 2006) indicate that adaptation of sexually dimorphic features may also contribute to their evolutionary trajectories. Indeed, genes expressed primarily in one sex (e.g., some escape genes in females) tend to evolve under adaptive pressure (reviewed in Ellegren and Parsch [2007]). Thus, we hypothesize that escape genes might be subject to a unique selective regime.

Here we compared selective pressure between genes with different XCI states using a nonsynonymous-to-synonymous substitution rate ratios (KA/KS) and gene expression data. X-linked genes were classified into inactivated, escape, or heterogeneous groups based on the rodent/human somatic cell hybrids assay and the primary human cell line assay (Carrel and Willard [2005]; methods as presented in supplementary fig. S1 and table S1, Supplementary Material online).

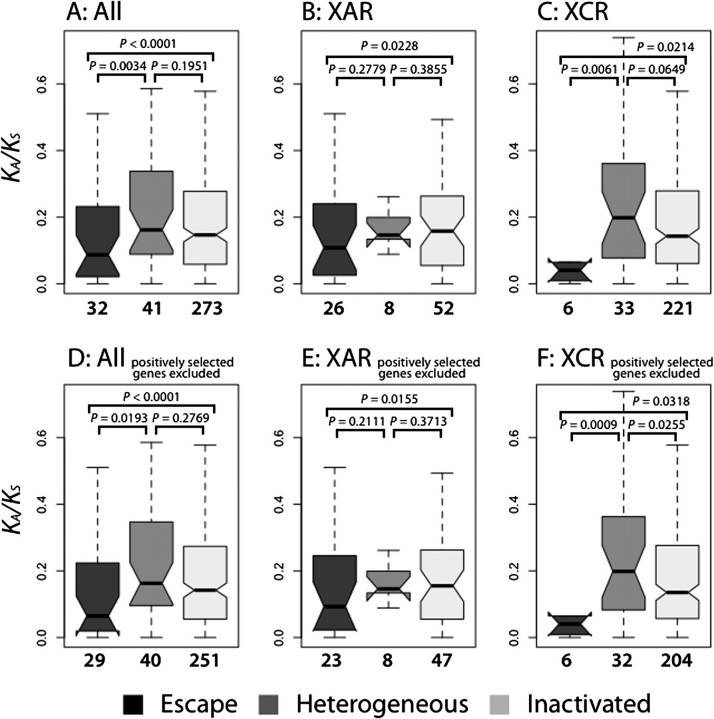

First, to contrast selective pressure between escape, heterogeneous, and inactivated genes, the KA/KS ratio in the human–chimpanzee–macaque phylogenetic tree was computed for each orthologous gene group (see Materials and Methods). Only genes with one-to-one orthology were utilized; the final data set included 346 genes (32 escape, 41 heterogeneous, and 273 inactivated genes; see Materials and Methods and supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). We assumed conservation of the XCI profile among primates (consistent with unpublished results from the Carrel laboratory). We observed (fig. 1A) that the median KA/KS ratio was significantly lower for escape genes than for either inactivated (0.087 vs. 0.147, P < 0.0001) or heterogeneous genes (0.087 vs. 0.162; P = 0.0034). All P values were computed with the permutation test (see Materials and Methods). The same comparison was repeated separately for newly X-specific genes located in the X-added region (XAR) and anciently X-specific genes in the X-conserved region (XCR; fig. 1B and C; Ross et al. [2005]). In both cases, the median KA/KS ratio was significantly lower for escape than inactivated genes (0.108 vs. 0.158 for XAR genes, P = 0.0228; 0.041 vs. 0.143 for XCR genes, P = 0.0214). This ratio was also lower for escape than heterogeneous genes for both XAR and XCR; the difference was significant for XCR genes (0.041 vs. 0.198; P = 0.0061) and nonsignificant for XAR genes (0.108 vs. 0.146; P = 0.2779), likely due to a small number of heterogeneous genes in the XAR. These findings suggest stronger purifying selection operating on escape than either inactivated or heterogeneous genes. Heterogeneous genes had KA/KS ratios not significantly different from those of inactivated genes (fig. 1A–C). When orthologous genes from orangutan and marmoset were added (see Materials and Methods), escape genes again had significantly lower median KA/KS ratios than inactivated genes (0.084 vs. 0.128; P = 0.0345; supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online); human–chimpanzee–macaque gene trios were used in the further analysis due to the high quality of these genome sequences.

FIG. 1.

A comparison of KA/KS ratios among escape, heterogeneous, and inactivated human–chimpanzee–macaque orthologous genes. (A) All orthologs. (B) Orthologs located in the X-added region (XAR). (C) Orthologs located in the XCR. (D) All orthologs excluding genes with positively selected codons. (E) Orthologs located in XAR excluding genes with positively selected codons. (F) Orthologs located in XCR excluding genes with positively selected codons. The number of genes considered is given below each plot. In the box plots, edges and vertical dashed lines represent quartiles and range, respectively. Notches indicate standard deviations of the median. Outliers are not shown.

Second, we addressed whether the above pattern could be due to positive selection preferentially acting on inactivated genes. Among the 346 genes tested, seven genes had KA/KS ratio greater than one, however, this was not significant for any gene (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). We also identified and excluded 26 genes with positively selected codons (see Materials and Methods and supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online). The remaining escape genes still had significantly lower KA/KS ratios than the remaining inactivated (0.065 vs. 0.142; P < 0.0001) or heterogeneous genes (0.065 vs. 0.163; P = 0.0193; fig. 1D) independent of gene location in XAR versus XCR (fig. 1E–F). Thus, positive selection does not seem to drive the observed lower KA/KS ratio for escape versus inactivated genes. Admittedly, the tests utilized here to test for positive selection are weak. However, our conclusions of its minimal role in our results are supported by generally low proportion of adaptive amino acid substitutions in hominoids (Zhang and Li 2005; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2009).

Third, as many escape genes have low inactive X relative to active X expression levels and are therefore essentially dosage compensated, we evaluated whether selection pressure varied based on differences in expression levels between males and females (Nguyen and Disteche 2006; Johnston et al. 2008). Lymphoblast expression microarray data, available for 23 out of 32 escape genes, was utilized to divide them into non-dosage compensated and dosage compensated (as in table 2 of Johnston et al. [2008]). We assumed the XCI pattern was the same between fibroblast and lymphoblastoid cells (although see Talebizadeh, Simon, and Butler [2006]). Fifteen non–dosage-compensated escape genes (with expression levels significantly different between males and females; HDHD1A, STS, PNPLA4, CA5B, EIF1AX, EIF2S3, ZFX, USP9X, DDX3X, FUNDC1, UTX, UBE1, JARID1C, SMC1L1, and RPS4X) and 8 dosage-compensated ones (with expression levels not significantly different between males and females; RAB9A, SEDL, FAM51A1, AP1S2, CTPS2, RBBP7, MGC39350, and ARHGAP4) had similar KA/KS ratios (0.065 and 0.070, respectively). Thus, purifying selection in such genes does not depend on male–female expression differences.

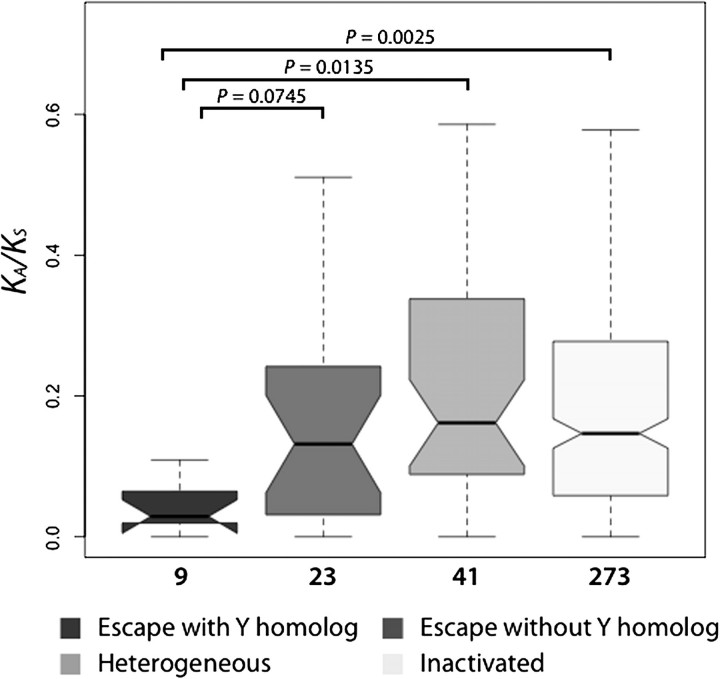

Fourth, to evaluate whether the possession of a Y homolog—another way to achieve dosage balance—might be related to the tendency to evolve under strong purifying selection, we compared KA/KS ratios between escape genes with versus without functional Y homologs (fig. 2), as classified in Ross et al. (2005). Nine escape genes with functional Y copies (NLGN4X, CXORF15, EIF1AX, ZFX, USP9X, DDX3X, UTX, SMCX, and RPS4X) had lower KA/KS ratios than the remaining 23 escape genes (0.029 vs. 0.132; P = 0.0745). Moreover, the median KA/KS ratio was significantly lower for escape genes with a Y homolog than for either inactivated genes (0.029 vs. 0.147; P = 0.0025) or heterogeneous genes (0.029 vs. 0.162; P = 0.0135), whereas the median KA/KS ratio was not significantly different for escape genes without Y homologs versus either inactivated genes or heterogeneous genes (data not shown). Thus, strong purifying selection in escape genes is primarily determined by existence of functional Y homologs.

FIG. 2.

A comparison of KA/KS ratios among escape genes with Y homologs, escape genes without Y homologs, heterogeneous genes, and inactivated genes (as computed for the human–chimpanzee–macaque orthologous trios). The number of genes considered is listed below each plot.

Because some factors mentioned above (i.e., XAR/XCR evolutionary strata, possession of a Y homolog, XCI status, and dosage balance) might correlate with each other, we performed a multiple regression analysis to evaluate the relative contribution of each factor to explain the total variability in the KA/KS ratio. Local recombination rate was also added to the model because recombination affects the efficacy of natural selection. Using all X-linked genes with three predictors (XAR/XCR strata, XCI status, and recombination rate; supplementary table S4, Supplementary Material online), we were able to predict only 1.5% of variation in KA/KS; however, the XCI status was the only marginally significant predictor. This is not surprising because our data set is overloaded by inactivated genes, thus diluting any signal attributed to escape genes. In a separate regression model, we considered escape genes separately and explained variation in their KA/KS with two predictors (possession of a Y homolog and dosage balance; table 1). This model explained 19.3% of variability in their KA/KS and indicated the possession of a Y homolog to be a significant predictor. Thus, the XCI status (Escape vs. non-Escape) and possession of a Y homolog are in part determining the KA/KS ratio of genes on the X.

Table 1.

Multiple Regression Models for KA/KS Ratio in X-Linked Genes.

NOTE.—RCVE, relative contribution to the variability explained; NS, not significant.

Y: existing versus not existing Y homolog.

Dosage: dosage-compensated versus non-dosage compensated.

Fifth, we questioned whether escape genes with Y-linked homologs influence selection acting on neighboring escape genes. This is of particular interest because escape genes are clustered, with each cluster containing an escape gene with a functional Y homolog (Carrel and Willard 2005). We investigated the KA/KS ratios in six clusters, each including at least one escape gene with a functional Y homolog and at least one additional escape gene (supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). For any cluster, the median difference in KA/KS ratios was not significantly different between an escape gene with a Y homolog and other escape genes belonging to the same cluster versus between an escape genes with a Y homolog and escape genes from other clusters (supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). Thus, escape genes with Y homologs do not determine the selective pressure of neighboring escape genes.

Finally, we examined whether distinct selective pressure acts on the expression of escape genes. Utilizing microarray expression data from brain, heart, kidney, and liver in six humans and five chimpanzees (Khaitovich et al. 2005), we compared the median ratio of human–chimpanzee expression divergence between escape and inactivated gene groups. In all four tissues, escape genes had lower expression divergence between species than inactivated genes (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online). This difference was significant for heart (0.227 vs. 0.298; P < 0.0001) and kidney (0.118 vs. 0.231; P < 0.0001) but not significant for brain (0.092 vs. 0.096; P = 0.4306) and liver (0.274 vs. 0.289; P = 0.4123). These findings suggest stronger selective constraints for not only the coding region but also the expression of escape over inactivated genes. Here we could not study heterogeneous genes and escape genes with Y homologs separately due to the paucity of tissue-specific data.

In summary, we observed that escape genes experience stronger purifying selection than inactivated genes at both the protein-coding and gene expression levels. This effect largely results from the importance of function and dosage of escape genes as observed when their gene dosage is altered in individuals with Turner syndrome (Good et al. 2003; Bondy 2006). Strong purifying selection acting at escape genes is primarily driven by genes possessing Y-linked homologs. Although some X and Y gametologous pairs retained similar functions (Watanabe et al. 1993; Sekiguchi et al. 2004), the majority of such pairs diverged in both function and expression (Wilson and Makova 2009). Y gametologs usually acquired male-specific functions (Skaletsky et al. 2003) and evolved more rapidly than the corresponding X homologs (Wyckoff et al. 2002; Wilson and Makova 2009). Thus, escape genes possessing Y homologs might evolve under strong purifying selection because they fulfill important functions different from their counterparts on the Y (see supplementary table S6 here and table S4, Supplementary Material online, in Wilson and Makova [2009]). This conclusion is further supported by the fact that most candidate genes for Turner syndrome have Y chromosome homologs (Burgoyne 1989; Fisher et al. 1990; Ellison et al. 1997; Rao et al. 1997).

Alternatively, or additionally, strong purifying selection acting on escape genes with Y homologs might be due to the dominance effect. Indeed, if we assume that such genes evolve largely like autosomal genes (i.e., Y copy provides a potent copy of its X chromosomal counterpart), then their dominance is distinct from this for inactivated genes, or escape genes without a Y homolog, whose expression is always hemizygous. Differences in dominance might lead to differences in the KA/KS ratio because mutations with small selective effects—such mutations are more likely to contribute to the nonsynonymous rate—tend to be more dominant (Kondrashov and Koonin 2004).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures S1–S3 and tables S1–S6 are available at Molecular Biology and Evolution online (http://www.mbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

We thank Melissa Wilson and Hiroki Goto for valuable discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01-HD056452).

References

- Bondy CA. Turner's syndrome and X chromosome-based differences in disease susceptibility. Gend Med. 2006;3:18–30. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(06)80191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne PS. Mammalian sex determination: thumbs down for zinc finger? Nature. 1989;342:860–862. doi: 10.1038/342860a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrel L, Willard HF. X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature. 2005;434:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature03479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H, Parsch J. The evolution of sex-biased genes and sex-biased gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:689–698. doi: 10.1038/nrg2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison JW, Wardak Z, Young MF, Gehron Robey P, Laig-Webster M, Chiong W. PHOG, a candidate gene for involvement in the short stature of Turner syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1341–1347. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.8.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD. Estimating the rate of adaptive molecular evolution in the presence of slightly deleterious mutations and population size change. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:2097–2108. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher EM, Beer-Romero P, Brown LG, Ridley A, McNeil JA, Lawrence JB, Willard HF, Bieber FR, Page DC. Homologous ribosomal protein genes on the human X and Y chromosomes: escape from X inactivation and possible implications for Turner syndrome. Cell. 1990;63:1205–1218. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90416-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good CD, Lawrence K, Thomas NS, Price CJ, Ashburner J, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS, Oreland L, Skuse DH. Dosage-sensitive X-linked locus influences the development of amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, and fear recognition in humans. Brain. 2003;126:2431–2446. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CM, Lovell FL, Leongamornlert DA, Stranger BE, Dermitzakis ET, Ross MT. Large-scale population study of human cell lines indicates that dosage compensation is virtually complete. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaitovich P, Hellmann I, Enard W, Nowick K, Leinweber M, Franz H, Weiss G, Lachmann M, Paabo S. Parallel patterns of evolution in the genomes and transcriptomes of humans and chimpanzees. Science. 2005;309:1850–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.1108296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov F, Koonin E. A common framework for understanding the origin of genetic dominance and evolutionary fates of gene duplications. TIG. 2004;20:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DK, Disteche CM. Dosage compensation of the active X chromosome in mammals. Nat Genet. 2006;38:47–53. doi: 10.1038/ng1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payer B, Lee JT. X chromosome dosage compensation: how mammals keep the balance. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:733–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao E, Weiss B, Fukami M, et al. (17 co-authors) Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:54–63. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MT, Grafham DV, Coffey AJ, et al. (282 co-authors) The DNA sequence of the human X chromosome. Nature. 2005;434:325–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi T, Iida H, Fukumura J, Nishimoto T. Human DDX3Y, the Y-encoded isoform of RNA helicase DDX3, rescues a hamster temperature-sensitive ET24 mutant cell line with a DDX3X mutation. Exp Cell Res. 2004;300:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaletsky H, Kuroda-Kawaguchi T, Minx PJ, et al. (40 co-authors) The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature. 2003;423:825–837. doi: 10.1038/nature01722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuse DH. X-linked genes and mental functioning. Hum Mol Genet. 2005 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi112. 14 Spec No. 1:R27–R23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talebizadeh Z, Simon SD, Butler MG. X chromosome gene expression in human tissues: male and female comparisons. Genomics. 2006;88:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Zinn AR, Page DC, Nishimoto T. Functional equivalence of human X- and Y-encoded isoforms of ribosomal protein S4 consistent with a role in Turner syndrome. Nat Genet. 1993;4:268–271. doi: 10.1038/ng0793-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, Makova KD. Evolution and survival on eutherian sex chromosomes. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff GJ, Li J, Wu CI. Molecular evolution of functional genes on the mammalian Y chromosome. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:1633–1636. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Disteche CM. Sex differences in brain expression of X- and Y-linked genes. Brain Res. 2006;1126:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li WH. Human SNPs reveal no evidence of frequent positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2504–2507. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.