Abstract

Objective

To describe prevalence and correlates of past year weapon involvement among adolescents seeking care in an inner-city ED.

Methods

This cross-sectional study administered a computerized survey to all eligible adolescents (age 14–18), seven days a week seeking care in the ED over an 18 month period in an inner-city Level 1 ED. Validated measures were administered including measures of demographics, sexual activity, substance use, injury, violent behavior and weapon carriage/use.

Results

Adolescents (N=2069, 86% response rate) completed the computerized survey. 55% were female; 56.5% were African American. In the past year, 20% of adolescents reported knife/razor carriage, 7% reported gun carriage, and 6% pulled a knife/gun on someone; zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression models were used to identify correlates of the occurrence and past year frequency of these weapon variables. Although gun carriage was more frequent among males, females were as likely to carry a knife or pull a weapon in the past year.

Conclusions

One fifth of all adolescent’s seeking care in this inner city ED have carried a weapon. Understanding weapon carriage among teens seeking ED care is a critical first step to future ED based injury prevention initiatives.

Keywords: Weapon, Adolescents, Violence, Emergency Department

Introduction

Youth violence is a significant public health problem that accounts for much of the morbidity and mortality among adolescents in the United States. Homicide is the leading cause of death for African-American adolescents and the second leading cause of death for Caucasian adolescents.1 Firearms are the most common mechanism of homicide mortality among adolescents, accounting for 83% of all homicides.1 Focusing on homicides alone, however, underestimates the scale of this public health problem among adolescents. In 2005, the ratio of nonfatal intentional injuries to homicides among adolescents was 101:1 suggesting the impact of violence on injury is far more substantial.2 Research indicates that fight-related injuries among adolescents carrying a knife occur at nearly twice the rate of injuries among adolescents that do not carry a weapon.3 Illicit gun and knife carriage are potent risk factors for violence and violent injury among adolescents3–8 and illicit gun carriage has been significantly associated with serious injury and death for both the carrier and others among adolescents.3, 4, 9, 10.

National medical organizations have recognized that firearm-related injuries and deaths affect the pediatric population and have urged physicians to incorporate violence prevention into adolescent medical practice.11–15 Identification of teens that carry weapons, specifically guns, is an important component of violence prevention. As a group, adolescents who present to the ED may differ from teens that attend school16 and have been shown to have elevated rates of risk behaviors.17

Previous research has not described weapon related behavior among a comprehensive sample of teens seeking ED care, regardless of presenting complaint. In addition analysis evaluating how risk factors relate to both if a teen has ever carried a weapon as well as how often a teen has carried has not been described in the adolescent literature. Weapon-related risk factors were selected for this current study based on theoretical models of youth violence/weapon carriage18–20 and prior research,3, 5, 6, 21–24 and included demographics (age, minority status, gender), prior injury and fighting, and other multiple risk behaviors such as substance and sexual activity. The main objective of this study is to describe the prevalence of weapon carriage among adolescents seeking care in an inner-city ED

Methods

Study Design

An observational cross-sectional survey was conducted.

Setting

The study site was an inner-city Level 1 trauma center ED in XXXXX, XXXXXXXX, with an annual ED census of approximately 75,000 patients per year (25,000 pediatric patients).The pediatric ED is a separate clinical area, adjacent to the adult ED (across the hall). XXX is the only public hospital in the city. XXXXX is comparable in terms of poverty and crime to the other urban centers such as Detroit, Hartford, Camden, St Louis, Oakland.25 The population of XXXXX is 50% African-American.26

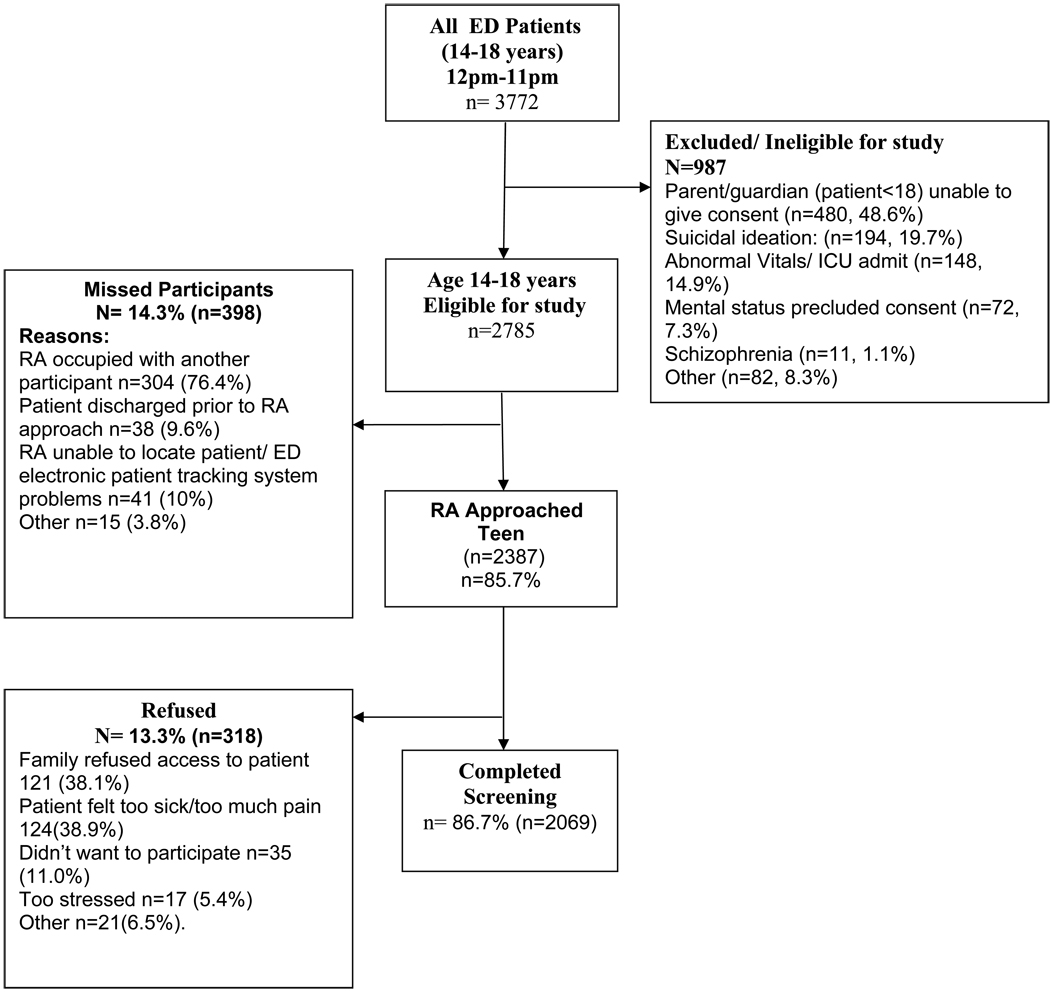

Patients were identified from electronic tracking logs and were approached by trained, bachelor or MA level research assistants (RAs) in waiting rooms or treatment spaces. A consecutive sample of adolescents (ages 14–18) presenting to the ED for either medical illness or injury were approached by research staff to participate in this computerized survey during the afternoon and evening shifts (~12pm– 11pm), seven days/week from September 06-June 08. Patients were excluded if they were being treated for sexual assault, acute suicidal ideation, or had abnormal vital signs (figure 1). Parental consent was obtained for youth under age 18. Study procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards (IRB). A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the NIH.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Flowchart - September 2006– June 2008

Methods of Measurement

Consenting participants self-administered an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) on a tablet laptop computer, with touch screen and audio via headphones. The median screen time was 12 minutes [inter-quartile range (IQR) =8.8 – 17.6). The survey administered was the screening portion of a larger RCT. Participants received a token $1.00 gift (e.g., notebook, pens). The survey was in English only (consistent with the study site population; no participants were excluded for language restrictions). RA staff paused the computer when medical staff was present or if participant went to testing (xray etc). Family or friends accompanying adolescent, if in the room, were not permitted to be in a physical position where they could view the questions in the computer. This was enforced by the RA in the room. If adolescents completed the screen more then once due to repeat ED visits over recruitment period, only the first screen completed was included in data.

Demographic information

(age, race, ethnicity, gender, employment, grades, and receipt of public assistance) was collected using items from the National Study of Adolescent Health.27

Weapon-related behaviors

were assessed using three questions from Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS),28 which have established reliability.29, 30 Participants were asked during the past 3 months and past year how often they; carried a knife/razor, carried a gun and pulled a knife or gun on someone. Past year carriage was the primary outcome variable. The response scale was: never, 1 time, 2 times, 3–5 times, 6–10 times, 11–20 times, and more than 20 times, For analysis purposes, past year carriage was the variable of interest; values used were the midpoints (ie for the range of 3– 5 times response 4 times was used) as is commonly done in the broader violence literature.31

Sexual activity

A question (yes/no) regarding lifetime sexual activity from the YRBS,28 was asked “Have you ever had sexual intercourse?”.

Substance use

Participants were asked to indicate whether they had consumed alcohol more than two or three times in the past year.27 Frequency, quantity, and heavy alcohol consumption were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C).32, 33 Binge drinking was assessed using the AUDIT-C;32 however, as recommended by Chung et al., 2002 for application among adolescents, binge drinking quantity was lowered from the original “6 or more…” to “5 or more drinks on one occasion”. Responses for binge drinking were dichotomized (yes/ no) for analysis. Past year cigarette34 and marijuana use28 were assessed using dichotomous measures indicating if the substance was used (yes or no).

Injury

Past-year injury from a physical fight or a gun was assessed with the Adolescent Injury Checklist.35 Patients indicated if injuries required treatment by a doctor/nurse. These were dichotomized (yes/no).

Violent Behavior

Two items from Add Health27 assessed how often the teens self report they were in a “serious physical fight” and “took part in a fight where a group of my friends was against another group.” Consistent with the Add Health survey these behaviors were not further defined. Responses were dichotomized (yes/no).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for demographic and behavioral characteristics of the sample (Table 1), and three outcome variables (knife/razor carriage, gun carriage, pulled a knife or gun). Bivariate analyses were performed using chi square test of independence. Zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression models were then used to predict both the past year occurrence as well as past year frequency of the three outcomes listed above. ZIP regression is indicated when there is a high likelihood that there will be multiple scores of zero.36 ZIP regression was chosen here as it allows for two types of predictions: whether or not a behavior occurred (e.g., gun carriage), where associations are interpreted with odds ratios for predicting “zero” for the outcome (e.g., no gun carriage) and appear in the “Zero-Inflation” column ; and, for those who reported the occurrence of a given behavior, how often it occurred (e.g., how often carried a weapon), for which associations are interpreted with a relative risk ratio, and are reported in the “incident count” column. This analysis thus provides novel information on gun carriage among adolescents in general, and specifically in this ED sample The Vuong statistic37 (z=13.43, p<0.0001 for knife carriage; z=4.93, p<0.0001 for gun carriage; and z=5.61, p<0.0001 for pulling a weapon) was used to confirm that the ZIP regression models were the most appropriate regression models to use given the distribution of the variable.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample (n=2069)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (16 and older) | 1270 (61.4) |

| Race (African American) | 1170 (56.5) |

| Gender (Male) | 929 (44.9) |

| Failing grades in school | 652 (31.5) |

| Employed | 522 (25.2) |

| Public assistance | 1104 (53.4) |

| Past-year substance use | |

| Any alcohol use | 585 (28.3) |

| Binge drinking | 302 (14.6) |

| Cigarette use | 546 (26.4) |

| Marijuana use | 593 (28.7) |

| Past-year injury | |

| Injured in a physical fight | 336 (16.2) |

| Injured in a physical fight & treated by doctor/nurse |

89 (4.3) |

| Injured by a gun | 165 (8.0) |

| Violent Behavior | |

| Serious physical fight | 807 (39.0) |

| Group fighting | 438 (21.2) |

| Sexual activity ( yes) | 1254 (60.6) |

Independent variables were retained in the final regression models based on theory,18–20 and significance in the bivariate analysis. All demographic factors (i.e., age, race, gender, and receipt of public assistance) were associated with at least one of the three weapon-related behaviors in the bivariate analysis and given the theoretically grounded importance of controlling for these variables, all demographic variables were retained in all multivariate models. Substance use variables (cigarette use, marijuana use, alcohol use, and binge drinking,) were highly correlated. To account for this, marijuana use and binge drinking were retained in the final model (dropping cigarette and alcohol use) as the former variables had the strongest bivariate association with weapon behaviors. Multicollinearity diagnostics were calculated on all variables retained in final regressions ( see table 3) and there was no evidence of multicollinearity.

Table 3.

Zero-Inflated Poisson regression predicting past year knife/razor carriage, gun carriage and pulling a weapon. (N= 2069)

| Knife/razor carriage (n=272) |

Handgun carriage (n=144) |

Pulled a knife/razor/gun (n=131) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Inflation | Incident count | Zero-Inflation | Incident count | Zero-Inflation | Incident count | |

| Demographics | OR ( CI) | RR( CI) | OR( CI) | RR( CI) | OR( CI) | RR( CI) |

| Age (16 and older) | 0.92 (0.69–1.20) | 1.49 (1.37–1.61) | 0.75 (0.47–1.20) | 1.30 (1.08–1.56) | 0.74 (0.43–1.25) | 1.79 (1.39–2.57) |

| Race (African American) |

0.64 (0.50–0.83) | 0.60 (0.55–0.64) | 2.44 (1.54–4.00) | 1.06 (0.95–1.26) | 1.89 (1.16–3.03) | 0.95 (0.72–1.27) |

| Gender (Male) | 0.85 (0.67–1.09) | 1.23 (1.14–1.32) | 7.14 (4.35–11.11) | 1.29 (1.06–1.59) | 1.28 (0.82–1.96) | 1.63 (1.25–2.14) |

| Failing grades in school | 1.30 (1.02–1.67) | 1.13 (1.061.21) | 1.52 (1.01–2.27) | 1.58 (1.35–1.85) | 0.94 (0.61–1.47) | 1.72(1.31–2.27) |

| Employed | 1.09 (0.83–1.41) | 1.13(1.05–1.21) | 0.73 (0.45–1.19) | 1.35 (1.14–1.59) | 0.98 (0.58–1.64) | 1.53(1.11–2.11) |

| Public assistance | 0.98 (0.76–1.23) | 0.99 (0.93–1.07) | 0.82 (0.54–1.23) | 1.82(1.59–2.13) | 1.43 (0.92–2.22) | 1.96 (1.54–2.50) |

|

Past-year substance use |

||||||

| Marijuana use | 2.27(1.72–3.03) | 1.32(1.22–1.42) | 3.33 (2.13–5.26) | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 2.38 (1.45–4.00) | 1.28 (0.94–1.73) |

| Binge drinking | 1.09 (0.78–1.49) | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | 1.54 (0.93–2.56) | 1.33(1.12–1.59) | 2.27 (1.33–3.85) | 0.78(0.58–1.05) |

| Past-year injury | ||||||

| Injured in a physical fight | 1.09 (0.65–1.79) | 1.06(0.82–1.08) | 1.79 (0.83–3.85) | 1.82 (1.29–2.59) | 1.47 (0.70–3.03) | 1.16(1.11–1.84) |

| Injured by a gun | 1.67 (1.15–2.44) | 0.95(0.86–1.04) | 1.89 (1.12–3.23) | 1.19 (1.01–1.41) | 1.09 (0.61–1.92) | 1.65(1.25–2.18) |

| Violent Behavior | ||||||

| Serious physical fight | 1.92 (1.47–2.50) | 0.95(0.87–1.02) | 1.61 (1.02–2.56) | 1.33 (1.12–1.59) | 1.61 (0.92–2.86) | 2.14(1.39–3.29) |

| Group fighting | 1.92 (1.47–2.56) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 3.33 (2.13–5.00) | 1.64 (1.36–1.98) | 2.78 (1.75–4.55) | 1.55 (1.11–2.16) |

| Sexual activity (Yes) | 1.49 (1.10–2.04) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 2.44 (1.32–4.55) | 1.26 (0.95–1.68) | 0.93 (0.46–1.85) | 1.97 (1.23–3.16) |

Note Zero inflated columns are predicting the occurrence of the behavior ( with Odds Ratio) while the “Incident Count” columns refer to how often the behavior occurred in those teens who reported the weapon related behavior ( with relative risk ratios). For example, past year injury by a gun was associated with occurrence of handgun carriage (OR=1.89), as well as with how often the teen carried (OR= 1.19)

Results

Among 2785 potentially eligible patients who presented during the recruitment period, 86% (n=2387) were approached (Figure 1). Among eligible patients who were approached, n=2069 completed the survey (86.7% participation, 13.3% refusal rate, 14.3% (n=398) were missed by the RA and therefore 74.2% of the focus population was included in the survey. Comparisons between the screening sample and refusals indicated the groups were similar by gender (X2=2.09, p=0.15) and race (X2=1.15, p=0.56). Due to IRB restrictions, no other data were collected on refusals without informed assent/consent. Among the sample, 55.1% were female and 56.5% were African American, 34.6% were Caucasian, and 8.8% were of other races (Table 1). In regard to ethnicity, 6.0% of teens identified as Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. Consistent with national trends,38 40% of participants presented to the ED seeking care for an injury.

Prevalence of Weapon-Related Behaviors

One fifth of all teens (n=414; 20.0%) reported knife/razor carriage (21.9% with a medical complaint, 16.7% of those with injury); 7% of all teens (n=144) reported past year gun carriage (6.2% with a medical complaint, 7.0% with an injury) (Table 2). Of teens who reported carrying a gun, most (n=98; 68%) had done so in the past 3 months. Only 3.1% teens (65/2069) reported carrying both a gun and knife. Nearly half (42%; 61/144) of teens who carried a gun reported that this occurred at least three times. Of teens that carried a gun, 39% (n=56) pulled a weapon; of those who carried a knife, 21% (n=86) reported pulling a knife/gun.

Table 2.

Prevalence and gender differences in weapon access, carriage, and use (N= 2069)

| All Teens N=2069 |

Male†† n=929 |

Female†† n=1140 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %† | Median (Inter quartile Range) |

n | (%)† | Median (Inter quartile Range) |

n | (%)† | Median (Inter quartile Range) |

|

| Knife/razor carriage | 414 | 20.0 | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 186 | 20.0 | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 228 | 20.0 | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) |

| Handgun carriage | 144 | 7.0 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 118 | 12.7 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 26 | 2.3 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) |

| Pulled knife or gun | 131 | 6.3 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 65 | 7.0 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 66 | 5.8 | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) |

% noted are column percentages

no significant differences were found in median number of times of carrying gun, carrying knife and pull weapon difference between males and females

Gender & Weapon-Related Behaviors

Males were more likely (OR 6.2; CI 4.0–9.6) than females to report gun carriage (12.7% vs. 2.3%). Rates of knife/razor carriage or pulling a weapon did not differ significantly between genders. The majority (96.2%) of females reporting weapon carriage also carried a knife. Males who carried were divided in terms of weapon type: 46.1% (118/256) reporting carrying a gun and 72.7% (186/256) reporting carrying a knife. Only 18.8 % (48/256) males reported carrying both types of weapons over the past year.

ZIP Regression: Knife/Razor Carriage

ZIP regression models (Table 3) were overall significant for each of the three outcomes (Table 4 for overall model statistics). Non-African American race, failing grades, marijuana use and sexual activity were not only related to the occurrence of knife/razor carriage, but were also associated with an increased frequency of past year carriage. Past-year injury by a gun, serious physical fighting and group fighting were associated with knife/razor carriage, but not the frequency of knife carriage. Older age and employment status were associated only more frequent knife carriage among teens who carried, but were not associated with occurrence of any knife/razor carriage.

ZIP Regression: Gun Carriage

Demographic characteristics of teens who reported any gun carriage differed from those who carried a knife by race; African American teens were more likely to carry guns, while non-African American teens were more likely to carry a knife. Male gender was also related to occurrence and increased frequency of gun carriage. Poverty (as indicated by receipt of public assistance by the teen’s family) was not associated with any gun carriage, but was associated with increased past year frequency of gun carriage among those teens that reported carriage.

Marijuana use and sexual activity were both strongly related to occurrence of gun carriage; however, unlike knife carriage these behaviors were not related to increased frequency of gun carriage among those who were carrying. Unlike knife carriage, binge drinking, past injury in a physical fight, past injury by a gun, and fighting (both serious fight and group fights) were all associated with increased frequency of gun carriage.

ZIP Regression: Pulling a Weapon

Overall, we found fewer correlates of pulling a weapon than weapon carriage. African-American participants and those who reported marijuana use, binge drinking and group fighting were associated with any pulling of a weapon. Binge drinking was the only correlate associated with frequency of pulling a weapon that was not also associated with knife or gun carriage. The correlates of frequency of pulling a weapon were very similar to those reporting increased frequency of gun carriage.

Discussion

This study fills a gap in the literature by providing a comprehensive analysis of rates, and correlates of both occurrence and frequency of past year weapon carriage and use, in a large systematic sample of teens seeking care in an inner-city ED. Although weapon carriage has been studied in prior school based and community samples, this study is among the first to inform ED clinicians on the prevalence of weapon related behaviors in a general sample of teens seeking ED care, a critical step toward ED based youth violence prevention initiatives.

One-fifth of teens in this ED sample reported knife or razor carriage and 7% reported gun carriage in the past year. Clinicians should consider these rates of weapon involvement when discharging patients from the ED, particularly those with assault-related injury at risk for participation in retaliatory violence, or those with psychosocial issues that may threaten the safety of themselves and others, such as depression, aggressive behavior. Many (39%) of the teens who carried a gun also pulled out a weapon (implicitly to threaten or use), highlighting the importance of intervening with teens who report carriage. Although this study did not examine the context and outcome of the weapon related situation, the act of pulling a weapon out during an altercation can exacerbate the probability of serious injury to self or others regardless of initial intent.39, 40 While “protection” or “self defense” are the often the most common reasons adolescents report for carrying a weapon,41–43 any illicit weapon involvement during adolescence places teens at greater risk for injury and death relative to other forms of youth violence.3, 21

Consistent with prior research, gun carriage was predominantly, although not exclusively a male activity.44 Knife carriage, however, was similar among males and females; females were as likely to have pulled a weapon out as their male peers. These results suggest that injury prevention efforts which include weapon carriage may need to include both genders, although role plays and discussions with female teens may be more salient if focused on knife carriage. Weapon type also varied according to race, with African American teens more likely to carry guns while non-African American teens were more likely to carry a knife. Weapon choice among adolescents likely has multiple determinants, include access, socioeconomic factors, neighborhood characteristics, peer-group activities and motivation for carrying a weapon.45 Understanding racial and gender differences related to weapon type may help inform and tailor future behavioral interventions focused on decreasing illicit weapon carriage and related injury.

One-third of the study sample had failing grades which in other studies was associated with both knife and gun carriage.6, 46 Teens with failing grades may be underrepresented in school-based studies highlighting the importance of understanding the unique characteristics of ED samples to more finely direct future intervention research intended for ED settings. Receipt of public assistance by the teen’s family did not predict any gun carriage, but among youth who carried a gun, public assistance was associated with increased frequency of carriage.

Consistent with many prior studies on clustering of risk behaviors and youth delinquency,18, 47–51 substance use, sexual activity, and group fighting were all related to gun and knife carriage. This study adds to the broader literature on weapon carriage by analysis of both the presence of and frequency of risk domains in relation to weapon involvement. Prior research has demonstrated a pathway between marijuana use among African Americans and weapon carriage.52, 53 Yet, our data revealed that although these high-risk behaviors cluster together, (e.g., marijuana use and sexual activity), they were not related to how often teens carried a gun in the past year. These findings may suggest that although these risk behaviors commonly co-occur within youth, they are not driving the frequency of the behavior.

In contrast, past-year serious physical fighting, group fighting, fight-related injury, or injury by a gun were all related to how often a teen carried a gun or pulled a weapon. In this cross-sectional study, causality cannot be inferred; therefore, it is unclear if teens carry and pull a gun because of prior injury and thus the perceived need for self-protection, or if gun carriage or use caused the future injury. In either case, these findings in an ED sample, mirror findings from other disciplines in the strong association between prior assault- or gun-related injury with gun carriage,3, 4, 6–8, 54 and should be considered clinically when treating teens in the ED who are the victims of an assault- or gun-related violence.

The relationship between alcohol use and violence is well-established, and alcohol use by underage teens has been associated with weapon-related behavior in prior studies.6–8, 23, 46, 55–58 This data are the first to report that binge drinking was related to increased frequency of carriage among teens that are carrying, as well as to the often impulsive behavior of pulling a weapon. Future studies are needed to determine whether this relationship reflects acute intoxication effects in which inebriated teens may impulsively carry or pull an illicit weapon or simply reflect the clustering of risk behaviors. Clinically, these findings suggest that substance use interventions addressing binge drinking among high-risk teens may also be effective in reducing frequency of gun carriage and perhaps the likelihood that a teen will pull out a gun in an altercation.

Limitations

This study was limited by its cross-sectional design therefore causal connections about gun carriage could not be made, and the context of weapon carriage or use was not assessed. Prospective studies testing the predictive validity of the screening tool are necessary in a separate data set. Teens presenting with acute suicidal ideation or attempt were also excluded from the study therefore the rates presented may be an underestimate of rates of weapon related behaviors. The behaviors are self-reported, however recent reviews among adolescents and young adults have concluded that reliability and validity of risk behaviors such as self-reported alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use is high59–63 and adolescents and young adults are more likely to report risky behaviors using computerized surveys and when privacy/confidentiality is assured as was done with a NIH certificate of confidentiality in this study.63–67 This data reflects a single site, with predominantly African- American and Caucasian youth, and low numbers of Hispanic youth (consistent with the local population). No patients were excluded due to being non English speaking. In addition youth presenting on the overnight shift were not sampled in this study. However youth treated in the ER in the middle of the night may be less receptive and alert to hear prevention messages or participate in screening. Finally, although strength of this study is its focus on an inner-city ED, a logical focus for future violence prevention initiatives, the findings may not generalize to non inner city, urban, suburban or rural EDs.

Conclusions

This study is the first to describe rates and correlates of weapon carriage among over 2000 adolescents seeking ED care who were systematically approached and screened over 18 months in an inner city ED. One-fifth of teens surveyed reported weapon carriage, and 6% have pulled out a weapon in the past year. Female teens report similar rates of knife carriage compared to their male peers, and this should be accounted for in future injury prevention strategies. We found that being male, having been involved in a group fight, a serious fight, having been injured by a weapon, binge drinking, marijuana use and being sexually active, were all risk factors positively associated with gun carriage. Violent injury has been shown to be a preventable public health problem.68 Understanding weapon carriage among teens seeking ED care is a critical first step to future ED based injury prevention initiatives.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Cunningham had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project was supported by a grant (#014889) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). We would like to thank project staff Bianca Burch, Yvonne Madden, Tiffany Phelps, Carrie Smolenski, and Annette Solomon for their work on the project; also, we would like to thank Pat Bergeron for administrative assistance and Linping Duan for statistical support. Finally, special thanks are owed to the patients and medical staff at Hurley Medical Center for their support of this project.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Drs. Cunningham, Resko, Harrison wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Drs. Walton (PI), Zimmerman, and Chermack conceptualized the study, contributed to analysis plan and are investigators on the grant funding this work. Dr. Stanley assisted in editing the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Accessed March 28, 2008];Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. Ten leading causes of death. United States 2005. 2005 Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Accessed April 8, 2008];Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online] 2005 Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- 3.Lowry R, Powell KE, Kann L, et al. Weapon-carrying, physical fighting, and fight-related injury among U.S adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 1998 Feb;14(2):122–129. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickett W, Craig W, Harel Y, et al. Cross-national study of fighting and weapon carrying as determinants of adolescent injury. Pediatrics. 2005 Dec;116(6):e855–e863. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, Stuenkel K, et al. Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e392–e399. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuRant RH, Kahn J, Beckford PH, et al. The association of weapon carrying and fighting on school property and other health risk and problem behaviors among high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997 Apr;151(4):360–366. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170410034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dukarm CP, Byrd RS, Auinger P, et al. Illicit substance use, gender, and the risk of violent behavior among adolescents. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:797–801. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170330023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forrest CB, Tambor E, Riley AW, et al. The health profile of incarcerated male youths. Pediatrics. 2000 Jan;105(1 Pt 3):286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng TL, Johnson S, Wright JL, et al. Assault-injured adolescents presenting to the emergency department: causes and circumstances. Acad Emerg Med. 2006 Jun;13(6):610–616. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durant RH, Getts AG, Cadenhead C, et al. The association between weapon carrying and the use of violence among adolescents living in and around public housing. J Adolesc Health. 1995 Dec;17(6):376–380. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00030-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Medical Association. Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Violence. The role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention in clinical practice and at the community level. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):173–181. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics. Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2000 Apr;105(4 Pt 1):888–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Family Physicians. Violence [position paper] [Accessed April 8, 2008];American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/policy/policies/v/violencepositionpaper.html.

- 15.American College of Emergency Physicians. Practice resources - Violence. [Accessed April 8, 2008];American College of Emergency Physicians. Available at: http://www.acep.org/practres.aspx?id=29848.

- 16.Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Thompson M, et al. Behavioral risk factors in emergency department patients: a multisite survey. Acad Emerg Med. 1998 Aug;5(8):781–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescents who use the emergency department as their usual source of care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Apr;154(4):361–365. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991 Dec;12(8):597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinman KJ, Zimmerman MA. Episodic and persistent gun-carrying among urban African-American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2003 May;32(5):356–364. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman MA, Morrel-Samuels S, Wong N, et al. Guns, Gangs, and Gossip: An Analysis of Student Essays on Youth Violence. J Early Adolescence. 2004 November;24(4):385–411. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlberg LL. Youth violence in the United States. Major trends, risk factors, and prevention approaches. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):259–272. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes DN, Sege R. FiGHTS: a preliminary screening tool for adolescent firearms-carrying. Ann Emerg Med. 2003 Dec;42(6):798–807. doi: 10.1016/S0196064403007224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon TR, Richardson JL, Dent CW, et al. Prospective psychosocial, interpersonal, and behavioral predictors of handgun carrying among adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1998 Jun;88(6):960–963. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sege R, Stringham P, Short S, et al. Ten years after: examination of adolescent screening questions that predict future violence-related injury. J Adolesc Health. 1999 Jun;24(6):395–402. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States 2006: Uniform Crime Report 2006. U.S. Department of Justice. Available at: http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2006/index.html.

- 26.Michigan Department of Community Health. Census 2000. 2002 Oct 31; Available at: http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/CHI/POP/Fcensus2.ASP, 10/31/2002.

- 27.Harris K, Florey F, Tabor J, et al. [Accessed 2008, May 21];The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design [WWW document] Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey. [Accessed November 4, 2007];Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbss.

- 29.Brener ND, Collins JL, Kann L, et al. Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:575–580. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, et al. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002 Oct;31(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straus MA, Gelles RJ. How violent are american families? Estimates from the National Family Violence Resurvey and other studies. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptation to violence in 8, 145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Sep 14;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Alcohol use disorders identification test: factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002 Feb;26(2):223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006. Volume 1: Secondary school students. 2007 NIH Publication No. 07-6205.

- 35.Jelalian E, Alday S, Spirito A, et al. Adolescent motor vehicle crashes: the relationship between behavioral factors and self-reported injury. J Adolesc Health. 2000 Aug;27(2):84–93. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez-Avila CA, Song C, Kuo L, et al. Targeted versus daily naltrexone: secondary analysis of effects on average daily drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006 May;30(5):860–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vuong QH. Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica. 1989;57:307–333. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 Emergency Department Summary. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammig BJ, Dahlberg LL, Swahn MH. Predictors of injury from fighting among adolescent males. Inj Prev. 2001 Dec;7(4):312–315. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.4.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheley JF, McGee ZT, Wright JD. Gun-related violence in and around inner-city schools. American journal of diseases of children (1960) 1992 Jun;146(6):677–682. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160180035012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon TR, Dent CW, Sussman S. Vulnerability to victimization, concurrent problem behaviors, and peer influence as predictors of in-school weapon carrying among high school students. Violence Vict. 1997 Fall;12(3):277–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheley JF, Wright JD. Motivations for gun possession and carrying among serious juvenile offenders. Behav Sci Law. 1993;11:375–388. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hemenway D, Miller M. Gun threats against and self-defense gun use by California adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Apr;158(4):395–400. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown B. Juveniles and Weapons: Recent Research, Conceptual Considerations, and Programmatic Interventions. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2004 April 1;2(2):161–184. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finkenbine RD, Dwyer RG. Adolescents who carry weapons to school: A review of cases. J School Violence. 2006;5(4):51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergstein JM, Hemenway D, Kennedy B, et al. Guns in young hands: a survey of urban teenagers' attitudes and behaviors related to handgun violence. J Trauma. 1996 Nov;41(5):794–798. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irwin CE. Adolescent Social Behavior and Health: New Directions for Child Development. Vol 37. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zucker RA, Chermack ST, Curran GM. Alcoholism: A lifespan perspective on etiology and course. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, Miller R, editors. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York: Plenum; 2000. pp. 569–587. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gabriel RM, Hopson T, Haskins M, et al. Building relationships and resilience in the prevention of youth violence. Am J Prev Med. 1996 Sep-Oct;12(5 Suppl):48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychological Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swahn MH, Simon TR, Hertz MF, et al. Linking dating violence, peer violence, and suicidal behaviors among high-risk youth. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Jan;34(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Estell DB, Farmer TW, Cairns BD, et al. Self-report weapon possession in school and patterns of early adolescent adjustment in rural african american youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003 Sep;32(3):442–452. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kulig J, Valentine J, Griffith J, et al. Predictive model of weapon carrying among urban high school students: results and validation. J Adolesc Health. 1998 Apr;22(4):312–319. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borowsky IW, Ireland M. Predictors of future fight-related injury among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004 Mar;113(3 Pt 1):530–536. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kingery PM, Pruitt BE, Heuberger G. A profile of rural Texas adolescents who carry handguns to school. J Sch Health. 1996 Jan;66(1):18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb06252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, et al. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 Dec;72(6):1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheley JF, Brewer VE. Possession and carrying of firearms among suburban youth. Public Health Rep. 1995 Jan-Feb;110(1):18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, et al. Correlates of aggressive and violent behaviors among public high school adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1995 Jan;16(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)94070-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gray TA, Wish ED. Substance Abuse Need for Treatment among Arrestees (SANTA) in Maryland. College Park, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. Duffee D, editor. The self-report method of measuring delinquency and crime. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice: Criminal Justice 2000. 2000:33–83.

- 61.Buchan BJ, M LD, Tims FM, et al. Cannabis use: consistency and validity of self-report, on-site urine testing and laboratory testing. Addiction. 2002 Dec;97 Suppl 1:98–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dennis M, Titus JC, Diamond G, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) experiment: rationale, study design and analysis plans. Addiction. 2002 Dec;97 Suppl 1:16–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Dec;33(6):436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, et al. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998 May 8;280(5365):867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wright SW, Norton VC, Dake AD, et al. Alcohol on campus: alcohol-related emergencies in undergraduate college students. South Med J. 1998 Oct;91(10):909–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webb PM, Zimet GD, Fortenberry JD, et al. Comparability of a computer-assisted versus written method for collecting health behavior information from adolescent patients. J Adolesc Health. 1999 Jun;24(6):383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harrison LD, Martin SS, Enev T, et al. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population. 2007 Department of Health and Human Services Publication No. SMA 07-4249, Methodology Series M-7.

- 68.Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence. Blueprints for violence prevention. [Accessed July 8, 2005];University of Colorado at Boulder Web site. Available at: http://www.colorado.edu/cspv/blueprints/index.html.