Abstract

Alcohol use and violent behaviors are well documented among inner city adolescents and have enormous effect on morbidity and mortality.

OBJECTIVES

We hypothesize that universal computer screening of teens in an inner city ED, followed by a brief intervention (BI) for violence & alcohol will be: 1) feasible (as measured by participation and completion of BI during the ED visit) and well received by teens (as measured by post-test process measures of intervention acceptability); and 2) effective at significantly changing known precursors to behavior change such as attitudes, self-efficacy, and readiness to change alcohol use and violence 3-months following the ED-based BI.

METHODS

Patients (ages 14–18, 3–11 shift, 7 days/week), at an Urban Level 1 ED (Sept 06–Nov 08) were approached to complete a computerized survey. Adolescents reporting past year alcohol use and violence were randomized to a control group, or a ~35 minute BI delivered by a computer or therapist as part of the SafERteens study.

Measures

Validated measures were administered including: demographics, alcohol use, attitudes toward alcohol and violence, self-efficacy for alcohol and violence, readiness to change alcohol and violence, and BI process questions, including likeability of intervention.

RESULTS

2423 adolescents were screened (13% refused): 45% male; 58% African-American and 6.2% Hispanic. Of those screened, 637 adolescents (26%) screened positive; 533 were randomized to participate and 515 completed the BI prior to discharge. The BIs were well received by the adolescents; overall, 97% of those randomized to a BI self-reported that they found one intervention section “very helpful”. At post-test, significant reductions in positive attitudes for alcohol use and violence and significant increases in self-efficacy related to alcohol/violence were found in both the therapist and computer BI conditions. At 3-month follow-up (81% retention), as compared to the control condition, generalized estimating equations (GEE) analysis showed participants in both BI conditions showed significant reductions in positive attitudes for alcohol use (therapist p=0.002, computer p=0.0001) and violence (therapist p=0.012, computer p=0.007) and significant increases in self-efficacy related to violence(therapist p=0.0.04, computer p=0.002); alcohol self-efficacy improved in the therapist BI condition only (therapist p=0.050, computer p=0.083). Readiness to change was not significant.

CONCLUSIONS

This initial evaluation of the SafERteens study shows that universal computerized screening and BI for multiple risk behaviors among adolescents is feasible, well received, and effective at altering attitudes and self-efficacy. Future evaluations of the SafERteens study will evaluate the interventions effect on behavioral change (alcohol use and violence) over the year following the ED visit.

Keywords: Adolescents, Youth Violence, Alcohol, Emergency Department

Introduction

In the United States, there are over 100 million emergency department (ED) visits each year; 3 million are the result of violence.1 In 2004, of all causes of mortality among youth, 71% were due to preventable injury.2 Intentional injury is the leading cause of death among African-American adolescents and the second leading cause of death among Caucasian adolescents.3 Although injury prevention programs have historically relied on primary care providers, adolescent programs initiated or occurring during an ED visit are increasing in number.4–9 Adolescents who present to the ED for care may be more likely to engage in risk behaviors relative to other adolescents10, 11 and ED-based injury prevention programs may provide access to adolescents who lack a primary care physician, as well as those who do not regularly attend school.

Alcohol use is associated with the four leading causes of death among adolescents including homicide.12 The relationship between alcohol and violence can be explained by theories of problem behavior clustering as well as alcohol’s pharmacological effects.13–16 Prior research has found almost half of adolescent drinkers are also involved in violent behaviors (e.g., physical fighting)17 and adolescents who use alcohol and report violent behaviors are at increased risk for other drug use11, 18–20 and injury 21, 22 during adolescence and into adulthood.23, 24 Screening and brief intervention (BI) approaches focusing on both alcohol use and violent behaviors during adolescence could potentially prevent the progression of alcohol problems and more lethal assaultive injury.18, 19, 25, 26

Crucial to the translation of effective ED-based BIs to routine practice is incorporating strategies to systematically deliver BIs with inherent fidelity and feasibility, particularly given the current clinical demands on staff in busy, often overcrowded and under-resourced, inner city EDs. The use of computer technology for both screening and BI is one such strategy that is relatively untested among increasingly technology savvy adolescents.

The goals of this study were to: 1) demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of delivering a BI for alcohol and violence among adolescents during the ED visit via two modalities, computer or therapist; 2) provide a detailed intervention description including the key elements and theoretical grounding of the BIs, and the methods for computer screening and intervention; and, 3) report initial findings from the randomized controlled trial (the SafERteens Study) evaluating the effectiveness of the BIs at post-test and 3-month follow-up on attitudes, self-efficacy, and readiness to change.

We hypothesize that universal computer screening of all teens (ages 14–18) in an inner city ED, followed by a BI for alcohol and violence will be: 1) feasible (as measured by participation and completion of a BI during the ED visit) and well received by teens (as measured by post test process measures of intervention acceptability); and 2) will be effective at significantly changing known precursors to behavior change such as attitudes, self-efficacy, and readiness to change alcohol use and violence 3-months following the BI in the ED. This manuscript aims to provide detailed description of the SafERteens intervention including methods used in computerized screening and intervention delivery with adolescents, as well as preliminary outcomes (precursors to behavior change) such as attitudes, self efficacy, and stage of change). Follow up interviews of SafERTeens RCT are ongoing and future data collection will evaluate the intervention described here on behavioral outcomes (alcohol and violence) over 12 months.

METHODS

Study Setting

This randomized control trial (“SafERteens”) took place at Hurley Medical Center (HMC) ED in Flint, Michigan, a 540-bed teaching hospital and Level I Trauma Center. This site has a pediatric ED physically adjacent (across the hall) from an adult ED. The site has 75,000 total visits/year of which ~25,000 are pediatric (age 0- 17yrs). Study procedures were approved and conducted in compliance with the guidelines of the University of Michigan and HMC, Institutional Review Boards (IRB), for Human Subjects. A NIH Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Population

Patients ages 14–18 presenting to the ED for either medical illness or injury were eligible for the screening survey. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, abnormal vital signs, or were being treated for sexual assault or acute suicidal ideation. All patients who had normal vital signs were initially approached, including trauma patients after initial stabilization. Patients were excluded due to high acuity as noted in figure one (i.e. 18% had abnormal vital signs or were clearly being admitted to an ICU).

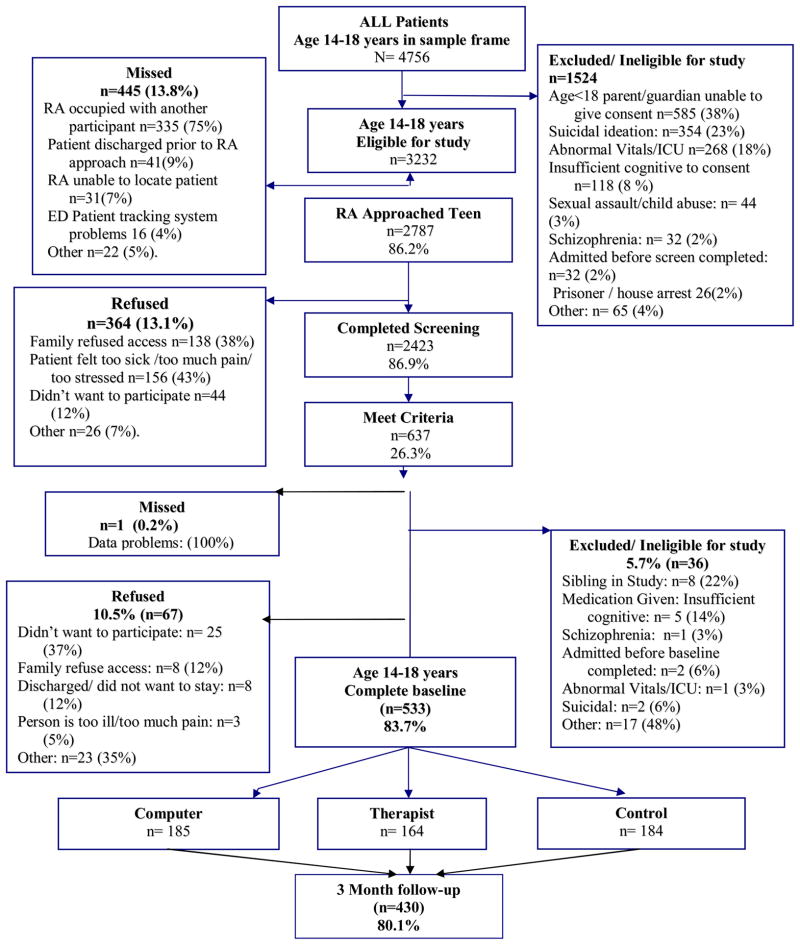

Figure 1.

Patient Flowchart September 2006 to Nov 2008.

Study Protocol

Recruitment took place from 12pm-11pm, seven days per week from 9/07-11/08 excluding major holidays. Patients were identified from electronic tracking logs and were approached by trained, bachelor or MA level research assistants (RAs) in waiting rooms or treatment spaces. RAs approached patients and obtained assent for phase one screening (and guardian consent if < 18). Consenting participants self-administered a 15-minute audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) on a tablet laptop computer, with touch screen and audio via headphones, in treatment spaces (room, hallways, bay) and received a $1.00 gift (e.g., notebook, pens).

Study Eligibility

After completion of the screening survey, participants who endorsed past year fighting (indicating any of the following violent behaviors in the past year: physical fighting, robbing, group fighting, pulling a knife or gun, shooting or stabbing) and past year alcohol use (i.e., drinking beer, wine or liquor, not just a sip or taste of someone else’s drink, more than 2 times in the past year) were eligible for the BI (see Measures).

Intervention Procedures

Following phase two assent/consent for the longitudinal study, participants completed a computerized baseline assessment and were randomized to one of three conditions while in the ED: computer (CBI), therapist (TBI), or control. Randomization to intervention group was stratified by gender and age block (14–15; 16–18). Patients assigned to the control condition were given a brochure containing information on alcohol and violence, and phone numbers for relevant community organizations. Participants in either intervention condition completed a brief post-test. Participants were paid $20 for the baseline interview. Participants were informed that they were not compensated for the intervention but for the baseline interview. If participants choose to leave at any time after randomization occurred including prior to completing the intervention they understood via the consent form they would still be compensated.

Follow up interviews

Computerized in person follow-up assessments were conducted at 3-months following the ED visit, either at the study ED or a community location convenient for the participant (e.g., library, fast food restaurant). Participants in all three groups (including control group) were remunerated $25 for the 3-month assessment at the time of assessment. Participants understood that RA staff would not view their responses to the 3- month assessment at any time including prior to compensation.

Measures

All assessments (screen, baseline, 3-month) and post-test (for CBI and TBI conditions) were administered by ACASI to ensure confidentiality, promote reporting of sometimes stigmatizing and illegal behaviors, allow for complex skip patterns, and decrease literacy burden.27–29 The measures were chosen with attention to prior research and validity and except where specifically noted were not changed, including the response scale, from the original cited format. Data were backed-up after each survey or intervention.

Demographics

Questions (i.e., age, race, ethnicity, gender, employment, grades, and receipt of public assistance) were collected using items from the National Study of Adolescent Health.30

Violent Behavior

Two items from Add Health30 assessed how often the adolescents got into a “serious physical fight” and “took part in a fight where a group of my friends was against another group.” Responses were dichotomized as yes or no. Current gang affiliation (yes/no) was assessed with one question.31

Weapon carriage and use

Weapon-related behaviors were assessed using questions adapted from Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBS),32 which has established reliability.33, 34 Participants were asked during past year how often they: carried a knife/razor, and how often they carried a gun.

Substance use

Participants were asked to indicate whether they had consumed alcohol more than two or three times in the past year.30 Frequency, quantity, and heavy alcohol consumption were assessed with three items from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C).35, 36 As recommended by Chung et al., (2002) for application among adolescents, binge drinking quantity was lowered from the original “6 or more…” to “5 or more drinks on one occasion”. Responses for binge drinking were dichotomized (yes/no) for analysis. Past year cigarette37 and illicit drug use (i.e., marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, hallucinogens)32 were assessed using dichotomous measures indicating if the individual substance was used (yes or no). The 6-item CRAFFT38 was used. Using a cut-off of 2 or higher, the CRAFFT demonstrates both, sensitivity (92%) and specificity (82%) in screening adolescents for substance-related problems.39

Past year Medical Service

Usage including primary care visits, ED visits, prior mental health or substance use counseling was assessed with 5 questions from Add Health30

Injury

Past-year violent injury (related to fighting or weapon use), was assessed with the Adolescent Injury Checklist.40 These were dichotomized as yes or no.

Attitudes

Alcohol use attitudes were assessed with five items (i.e., “Driving after drinking is safe as long as you pay attention.” “Most teens get drunk sometimes.”).41 Violence attitudes were assessed with 7 items (i.e., “If a person hits you, you should hit them back.”; “It’s okay to carry a gun or knife if you live in a rough neighborhood.”)42 Responses choices 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy for drinking alcohol was assessed using five items43 regarding “How sure are you that you could say no to drinking alcohol if…” (e.g., There were problems with your friends? There were problems with your family?; Someone made fun of you for not drinking?; All your friends were drinking?; You were worried about a problem you had?). The original response scale was expanded to a 5 point Likert scale to be consistent with the rest of the measures. Self-efficacy for non-violence was assessed with five items (i.e., “Staying out of fights”; “Calming down when mad,”).44 Responses choices included the original 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to extremely”.

Readiness to Change

Piloting of the measures section found that participants had difficulty understanding standard readiness rulers. 45 Therefore alcohol and violence readiness to change was each assessed instead using a, 5-point Likert item indicating: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (i.e., “Never think about my drinking; Sometimes I think about drinking less; I have decided to drink less; I am already trying to cut back on my drinking; My drinking has changed I now drink less than before.”) For violence, parallel response choices assessed readiness to change fighting.

Feasibility measures

The computer recorded times for the start and end of the survey and intervention. RAs recorded if they provided assistance with the computer condition.

Visit type

Current ED visit, medical illness (e.g., abdominal pain, asthma), or injury (ICD–9–CM E800–E999), was abstracted from the medical chart. Injury visits were classified as intentional (E950–E969) or unintentional (E800–E869, E880–E929). Chart reviews were audited regularly to maintain reliability in keeping with the criteria described by Gilbert and Lowenstein.46

A post-test was administered to both the CBI and TBI groups repeating the measures above for attitudes, self- efficacy and readiness to change for alcohol and violence as well as Process questions. Based on process measure used by Maio et al (2003)47 a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from “really didn’t like it” to “liked it a lot”), was used by participants to rate their received intervention condition. The helpfulness of individual intervention elements (i.e., “hearing how my fighting/drinking fits in with other adolescents my age”, “reviewing the reasons to change”, “going through role plays”, and “receiving information on resources in my community”) was also assessed on a 5-point scale (ranging from “not at all helpful” to “extremely helpful”) using a measure adapted from school based alcohol intervention literature48 to be specific to the elements of this intervention.

Description of SafERteens Intervention

Adapted motivational interviewing (AMI) based brief interventions have traditionally been delivered by therapists alone, or using a structured workbook and have been applied to alcohol but not to violence.9, 49, 50 AMI approaches mesh well with adolescent developmental issues such as desire for autonomy and independence, resistance to authority and lower tolerance for lengthy interventions. The framework for the SafERteens BI was based on principles of MI,51, 52 which focuses on enhancing motivation to change in a respectful, non-confrontational and non-judgemental manner, emphasizing choice and responsibility, supporting self-efficacy, developing a discrepancy between current behavior and future goals/values, rolling with resistance, and increasing problem recognition, motivation, and self-efficacy for change. The SafERteens BI also involved normative resetting and a skills training component whereby therapists asked participants to role-play responses to scenarios focusing on refusal skills for avoiding alcohol and alcohol-related risks, conflict resolution skills, and anger management skills.

This study examined two delivery modes of the BI (therapist and computer), designed to have the same content and organizational format, but with different modes of presentation (Table 1). They were developed specifically to be culturally relevant for inner city youth, who at this study site are ~ 50% African-American. Both delivery modes were developed and tested with focus groups composed of adolescents from the study ED (See online appendix for examples of intervention content).

Table 1.

Key Elements of SafERteens Interventions.

| Key Elements | Goal of element | Computer (C) and Therapist (T) Specific Content or Both (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction Agenda Setting ~2 min |

|

C: Participant selects Buddy (Appendix Image 1). T: Therapist introduction. |

| Personal Goals ~3–5 min |

|

B: BI goals listed. C: Buddy reiterates goals. T: Brief discussion of goals. |

| Personalized Feedback: Alcohol and Violence ~3–5min |

|

B: Gender/age appropriate graphs shown on screen. B: Reviewed (by T or C-Buddy) in a matter-of-fact, non-judgmental manner. T: Discuss how this currently or in the future could impact goals. C: Ask if think affects goals, check response on screen; reflective summary statements provided by Buddy (Appendix Image 2). |

| Reasons To Stay Away from Drinking and Fighting ~3–5 min |

|

B: Reasons for staying away from drinking and fighting presented on screen for participant to check. T: Use MI strategies to make a connection between reasons to avoid these behaviors and goals. C: Buddy summarizes the reasons checked on the screen to help make a connection between behaviors and goals. |

| Safer Choices; 5 Role Plays practicing risk reduction ~10–12min |

|

T: Role plays and options (parallel to those in C) are discussed C: Animated video game style. Character situations viewed. Decision points where participant is given opportunity to choose the next action. Participants may “choose” a negative choice (drinking, fighting), these choices are not viewed. Instead, Buddy gives feedback on consequences and how might affect goals. Participant chooses a better option, which is then animated. (Appendix Images 3 and 4) |

| Summarized Session & closing ~3–5 min |

|

T: Summary to reinforce change talk; support/advice to develop their “plan”. Review community resources with an emphasis on linkage addressing specific risk profile. C: Buddy summary of individual goals and reasons checked to stay away from drinking and fighting; encouraging follow-through with community resources handout. |

Therapist Condition (TBI)

Research therapists were trained in MI and skills training approaches at study onset, were monitored through monthly supervision, and participated in retraining workshops throughout the study. Therapists utilized a tablet laptop computer to provide personalized feedback from the screening and baseline surveys (e.g., violence and alcohol use patterns and consequences, goals, attitudes about alcohol and violence) as well as age- and gender-specific normative information. Adolescents completed computerized checklists identifying reasons to stay away from drinking and fighting. Using a pre-programmed algorithm, the computer selected a set of role-play scenarios based on the participant’s risk behaviors and the therapist guided the participant through them. For example, when participants reported weapon carriage, binge drinking or dating violence, therapists presented scenarios on these specific topics. To ensure that therapists maintained acceptable performance, therapy sessions were audio taped and coded by independent raters according to predetermined fidelity criteria and measures of adherence and competence.

Computer Condition (CBI)

An interactive multimedia computer program was developed for the study and viewed on tablet laptops, with touch screens and audio delivered through headphones to ensure participant privacy. The program was in narrated, cartoon style in which participants could choose a gender-, race-, and age-appropriate “buddy” to “hang out” with throughout the session. The buddy guided participants through the intervention elements, including review of tailored feedback based on survey responses, identifying reasons to stay away from drinking and fighting, and role play scenarios chosen by the computer based on reported risk behaviors (Table 1). During the scenarios, participants had to interact with peers and make behavioral choices. Feedback was provided about these behavioral choices by the buddy, with possible consequences highlighted and the best possible outcome demonstrated by the characters.

Data analysis

First, descriptive statistics were computed for demographic and behavioral characteristics of the sample. Second, analyses examined changes over time (baseline to 3-month follow up) for each of the intervention conditions (TBI, CBI) as well as for combined intervention sample at baseline as compared to post-test on: alcohol attitudes, violence attitudes, alcohol self-efficacy, and violence self-efficacy, alcohol readiness to change, and violence readiness to change. Nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon signed rank test) for paired differences were used pre/post because of the skewed nature of the outcome measures. Note that because the alcohol and violence readiness to change variables were skewed, with ~40% of participants indicating precontemplation, this variable was recoded to a 3-level variable: low (precontemplation), medium (contemplation, determination), and high (action/maintenance). Third, repeated measures analyses compared the effects of the intervention conditions with the control condition on 3-month outcomes on: alcohol attitudes, violence attitudes, alcohol self-efficacy, and violence self-efficacy, alcohol and violence readiness to change. An “intent to treat” approach was taken where all participants randomized to each condition were included regardless of if the condition was received (over 95% of participants received their assigned intervention). These analyses used regression modeling using generalized estimating equations (GEE) due to the correlated structure of our data from repeated measures at baseline and 3-month follow-up. The GEE methodology was introduced by Liang and Zeger (1986)53 to properly estimate the regression coefficient and variance of the regression coefficient when correlated data are used in regression analyses (SAS Version 9, particularly PROC GENMOD (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). This analysis used all data available for participants including those subjects lost to attrition. Appropriate distributions were used based on the nature and distribution of the response variable (e.g., negative binomial for alcohol self-efficacy, Poisson for other response variables).

Finally, Cohen’s effect sizes were calculated for outcomes that were found to be significant as described by (Hedges (1985).54 Based on prior prevention literature, an intervention effect size ≥0.10 was considered clinical meaningful.55–60 This manuscript reports the preliminary findings from the SafERteen study. This larger study is powered on 200/group to detect behavioral outcomes of self report violence and alcohol use at 12 months. The preliminary findings presented here are adequately powered, but not over-powered, to detect theoretically accepted precursors to behavior change, attitudes, and self-efficacy.

Results

Among 4756 potentially eligible patients who presented during the recruitment period, 86% (n=2787) were approached; 14% (n=445) were missed (Figure 1). The median screen time was 12 minutes [inter-quartile range (IQ) =8.8). Few adolescents required assistance with the computerized screening survey (8%; 180/2423). Comparisons between the screening sample and refusals indicated the groups were similar by gender (X2=2.09, p=0.15) and race (X2=1.27, p=0.54). Among the baseline sample (those eligible for randomization to study condition) (n=533), 42% were male and 55% were African-American, and 6.2% self identified as Hispanic ethnicity (Table 2). Consistent with the city population and pilot work at the site, No adolescents were excluded for being non- English speaking. The median time for completion of the baseline survey was 31 minutes (IQ=16.3).

Table 2.

Baseline Violence and Substance use Characteristics.

| Background Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Male | 223 (41.8%) |

| African-American | 293 (55.0%) |

| Caucasian | 198 (37.2%) |

| Other race | 42 (7.8%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 33 (6.2%) |

| Mean Age (SD) | 16.7 (1.3) |

| Family receipt of public assistance (yes) | 304 (57.0%) |

| Failing grades (some D’s & F’s)* | 104 (27.6%) |

| Dropped out of school | 52 (9.8%) |

| Live with parent | 440 (82.7%) |

| ED Characteristics | |

| Chief Complaint injury | 161 (30.2%) |

| Chief Complaint intentional injury | 37 (7.0%) |

| Past year any ED visit | 396 (74.3%) |

| Past year ED visit for injury | 294 (55.1%) |

| Discharged from ED on day of recruitment | 508 (95.4%) |

| Pain rating at ED visit ≥ 6 (range 1–10) | 351 (65.9%) |

| Past year Substance Use Characteristics | |

| Binge Drinking (5 or more drinks) | 280 (52.5%) |

| Screen positive for alcohol misuse CRAFFT ≥ 2 | 261 (49.0%) |

| Illicit drug use (yes) | 358 (67.2%) |

| Past year Violence/Delinquency | |

| Jail/juvenile detention | 79 (14.8%) |

| Serious physical fight | 329 (61.7%) |

| Group fighting | 199 (37.3%) |

| Gang affiliation (yes) | 34 (6.4%) |

| Weapon carriage | 258 (48.4%) |

| Violent injury | 201 (37.7%) |

Note: n=533.

Among those in school n=377.

Among those randomized to intervention conditions, 95% (n=331/349) completed the full intervention, and 94% (329/349) completed the post-test in the ED. Few adolescents required assistance with the intervention (6%; 22/349). The median time for the CBI intervention was 29 minutes (8.6) and the TBI was 37 minutes (18.9). RA staff did not note any negative comments from participants, parents or guardians, or ED staff with regard to the intervention delaying or interfering with routine clinical care. There was no damage by participants, family members, or visitors to the seven laptops used by participants for screening and intervention conditions, nor were there any attempted thefts.

Three-month follow-up assessments were completed with 81% (n=430) of adolescents. Of the 103 patients (19.3% of randomized baseline sample) who did not complete a 3-month follow up interview n= 99 were located and alive but were non-compliant with repeated attempts to complete the 3-month interview. One participant is incarcerated (and we do not have initial IRB approval to conduct interviews with incarcerated participants, or have information on alcohol involvement in reason for incarceration), and one patient was involved in a fatal motorcycle crash. Both participants were in the therapist condition. It is unknown if the participant involved in the crash was intoxicated, however family report notes the driver of the other vehicle in the crash was intoxicated. Two participants were not located at all post ED visit. Although their status is unknown, a search of the public online death registry databases, does not identify them.

Process measures of acceptability of intervention

Immediate post-test evaluation completed by adolescents randomized to the CBI or TBI conditions found that 97% of adolescents self-reported that at least one section of the intervention helpful and~ 80% reported at least one section “very helpful”. The two most well-liked elements of the interventions were reviewing the reasons to change drinking and fighting, and role-plays; 30% of adolescents rated these sections “extremely helpful”. Half (50%) of adolescents participating in the TBI condition gave it the highest rating (“Liked it a lot”), one-third (33%) “liked” it, and 16% rated it “OK”. In contrast, one-third (32%) of adolescents participating in the CBI condition reported that they “liked it a lot”, one-third “liked it” (34%), and 30% rated it “OK”. Fisher’s exact test comparing adolescents’ self-report ratings of the intervention found a larger proportion of adolescents in the TBI group rated the intervention as “liked it” (4 or more) than the adolescents in the CBI group (p<0.01).

Pre-test and Post-test for CBI and TBI conditions: Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Readiness to Change Alcohol and Violence

Paired comparisons between pre-test and post-test ratings of attitudes, self-efficacy and readiness to change for alcohol and violence were conducted for the CBI and TBI conditions. Results showed the BI successfully impacted alcohol attitudes (p<0.001) and violence attitudes (p<0.001), including weapon carriage, in both the CBI and TBI conditions (Table 3). In addition, increased self-efficacy scores related to avoiding fighting (p<0.001) and staying away from alcohol use (p<0.001) were observed in both CBI and TBI conditions. Readiness to change for alcohol and violence were not significant in either condition between pre-test and post-test.

Table 3.

Pre-test and Post-test Attitudes, Self-efficacy, and Readiness to Change.

| Follow-up | Both BI Conditions (n=329)++ | Therapist (n=152) | Computer (n=177) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol attitudes | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 2.89 (0.63) | 2.90 (0.64) | 2.88 (0.62) |

| Post-Test Mean (SD) | 2.51 (0.66) | 2.63 (0.62) | 2.40 (0.68) |

| Difference in Mean (SD) | 0.38 (0.68) | 0.27 (0.60) | 0.48(0.73) |

| % Change in Mean | 13.15%** | 9.31%* | 16.67%*** |

| Violence Attitudes | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 2.96 (0.79) | 3.02 (0.79) | 2.94 (0.82) |

| Post-Test Mean (SD) | 2.40 (0.82) | 2.42 (0.79) | 2.39 (0.84) |

| Difference in Mean(SD) | 0.56 (0.73) | 0.60 (0.68) | 0.55 (0.77) |

| % Change in Mean | 18.92 %*** | 19.87%*** | 18.71%*** |

| Self-Efficacy Alcohol | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 2.24 (1.21) | 2.14 (1.18) | 2.25 (1.22) |

| Post-Test Mean (SD) | 2.47 (1.12) | 2.46 (1.16) | 2.47 (1.07) |

| Difference in Mean | 0.23 (1.04) | 0.28 (0.99) | 0.18 (1.11) |

| % Change in Mean | 10.27%** | 13.08%** | 8.00%* |

| Self-Efficacy Fighting | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 2.37 (0.83) | 2.24 (0.79) | 2.41 (0.84) |

| Post-Test Mean (SD) | 2.68 (0.87) | 2.65 (0.81) | 2.70 (0.92) |

| Difference in Mean | 0.31 (0.71) | 0.41 (0.70) | 0.29(0.72) |

| % Change in Mean | 13.08%*** | 18.30%*** | 12.03%** |

| Readiness to change Alcohol | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 0.91 (0.87) | 0.88 (0.87) | 0.95 (0.87) |

| Post-Test Mean (SD) | 0.90 (0.82) | 0.99 (0.78) | 0.91 (0.84) |

| Difference in Mean (SD) | 0.01 (0.79) | 0.11 (0.52) | 0.04 (0.40) |

| % Change in Mean | 1.10% | 12.5% | 4.21% |

| Readiness to change Fighting | |||

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 1.04 (0.86) | 1.01 (0.86) | 1.03 (0.87) |

| Post-Test Mean (SD) | 0.95(0.84) | 0.80 (0.80) | 0.96 (0.87) |

| Difference in Mean (SD) | 0.09 (0.89) | 0.09 (0.89) | 0.07 (0.88) |

| % Change in Mean | 8.65% | 8.91% | 6.60% |

(6%) 20/349 of participants in the intervention groups (CBI, TBI) did not complete post-test.

p ≤ 0.05

p ≤ 0.01

Baseline and 3-Month RCT Outcomes: Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Readiness to Change for Alcohol and Violence

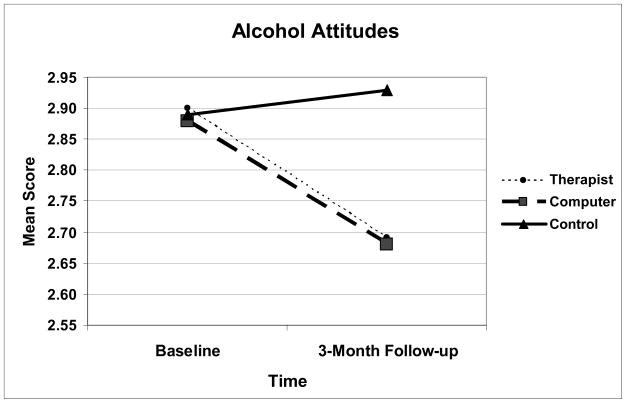

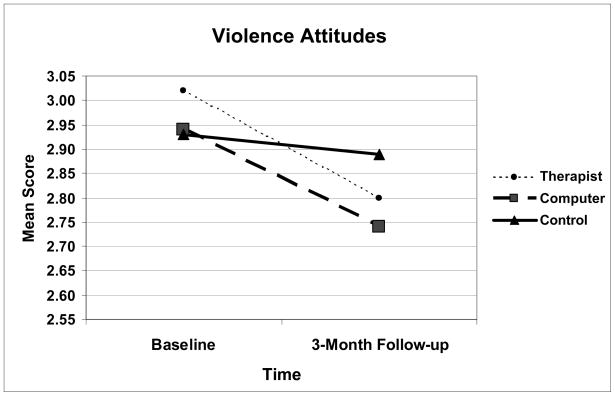

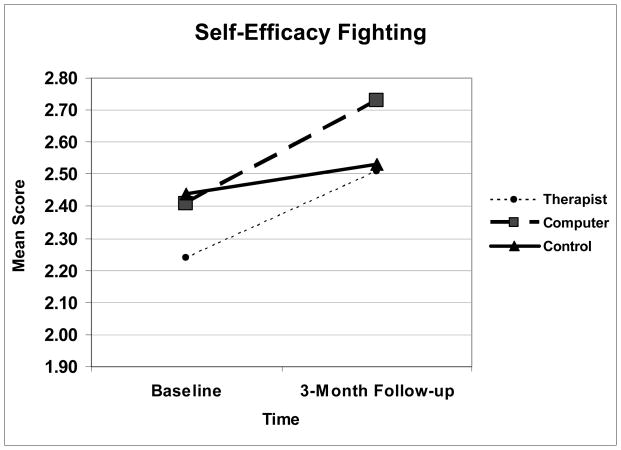

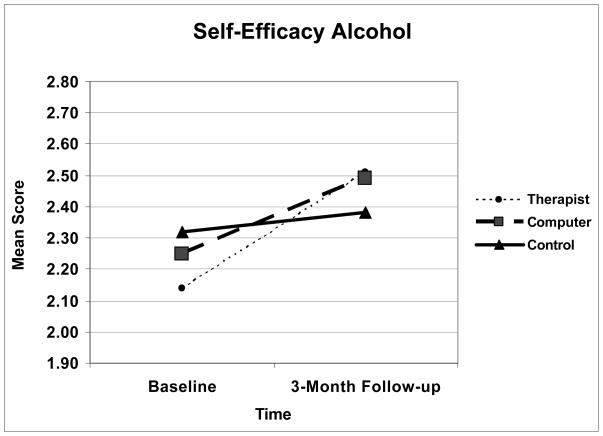

Repeated measures analyses (GEE models) were conducted comparing baseline and 3-month follow-up measures of attitudes, self-efficacy, and readiness to change alcohol use and violence for the intervention conditions (TBI, CBI) as compared to the control group. The overall group by time interaction effect was significant for alcohol attitudes (p<.001), violence attitudes (p<.01) including weapon carriage, and violence self-efficacy (p<.01) (Table 4); also, specific group by time interaction effects for computer and therapist conditions were significant for these variables. Those in the CBI and TBI condition significantly changed their attitudes for alcohol use and violence as compared to the control group (Table 4, Figures 2 & 3). Further, the TBI and CBI groups showed marked increases in self-efficacy for avoiding violence as compared to the control condition (Figure 4). Although the overall group X time interaction effect was not significant for alcohol self-efficacy (p=.11), the specific TBI group by time interaction effect was p=.05, and the CBI effect was p=.08. The TBI condition showed greater increases in alcohol self-efficacy than the control condition (Figure 5). Finally, analyses for readiness to change for alcohol and violence were not significant.

Table 4.

Baseline and 3-Month Follow-up Changes in Attitudes, Self- Efficacy and Stage of Change for Intervention Conditions compared to Control.

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 3-months Mean (SD) | Time * Group Interaction Effect (p-value) | Effect Size ** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol attitudes | ||||

| Therapist | 2.90 (0.64) | 2.69 (0.63) | 0.002 | 0.39 |

| Computer | 2.88 (0.62) | 2.68 (0.63) | 0.0001 | 0.39 |

| Control | 2.89 (0.62) | 2.93 (0.69) | ||

| Violence Attitudes | ||||

| Therapist | 3.02 (0.79) | 2.80 (0.91) | 0.012 | 0.25 |

| Computer | 2.94 (0.82) | 2.74 (0.86) | 0.007 | 0.22 |

| Control | 2.93 (0.76) | 2.89 (0.77) | ||

| Self-Efficacy Alcohol | ||||

| Therapist | 2.14 (1.18) | 2.51 (1.32) | 0.050 | 0.20 |

| Computer | 2.25 (1.22) | 2.49 (1.35) | 0.083 | |

| Control | 2.32 (1.21) | 2.38 (1.34) | ||

| Self-Efficacy Fighting | ||||

| Therapist | 2.24(0.79) | 2.51 (0.87) | 0.041 | 0.22 |

| Computer | 2.41 (0.84) | 2.73 (0.83) | 0.002 | 0.31 |

| Control | 2.44 (0.85) | 2.53 (0.84) | ||

| Readiness to change Alcohol | ||||

| Therapist | 1.88 (0.87) | 1.89(0.89) | 0.4945 | |

| Computer | 1.95 (0.89) | 1.83 (0.86) | 0.6843 | |

| Control | 1.92 (0.86) | 1.87 (0.92) | ||

| Readiness to change Fighting | ||||

| Therapist | 1.01 (0.86) | 1.03 (0.93) | 0.5803 | |

| Computer | 1.03 (0.87) | 0.91 (0.89) | 0.5798 | |

| Control | 1.07(0.87) | 1.01 (0.88) | ||

n=409.

Note: the group by time interaction effect is presented which tests the significance of change over time in scores, accounting for potential baseline group differences.

Attitudes: Decreased mean represents successful change in attitudes.

Self Efficacy: Improved mean score represents increased confidence in avoiding fights and avoiding drinking.

noted only for outcomes with significant change

Figure 2.

Note. Decreased mean represents successful change in attitudes.

Figure 3.

Note. Decreased mean represents successful change in attitudes.

Figure 4.

Note. Improved mean score represents increased confidence in avoiding fights.

Figure 5.

Note. Improved mean score represents increased confidence in avoiding drinking.

Discussion

Intentional injury is the leading cause of death among adolescents seeking care in an inner city ED. Alcohol use is associated with intentional injury as well as the other leading causes of death among adolescents (e.g., unintentional injury, suicide).12 Although adolescents in this study presented to the ED for many reasons, rates of risk behaviors (i.e., 53% binge drinking, 62% serious physical fighting, and 48% carrying a weapon) were elevated compared to national samples, where 26% of adolescents report binge drinking (5 or more drinks) in the past month61, 36% report being in a physical fight,61 and 19% report carrying a weapon.61 This risk profile along with high rates of injury (37% past year violent injury) and ED utilization (74% past year ED visit), in concert with the reduced likelihood that these teens will receive prevention messages in school settings (38% have dropped out or report failing grades), supports the importance of the ED visit as a opportunity for prevention efforts regardless of reason for visit. Despite this exacerbated risk, the adolescents in this study do not appear to be as far along the problem behavior spectrum as those in other ED based efforts focusing on assault injured adolescents7, 8, 62 and therefore may be responsive to a single brief intervention.

In contrast to research among adult ED samples (for reviews see Havard63; Nilsen64), few studies have examined therapist-delivered BIs for at-risk adolescents in the ED. Adolescents’ drinking behaviors and patterns differ from those of adults, which is important in determining BI content.50, 65 Among older adolescents (>16yrs of age) presenting to the ED for alcohol-related reasons, therapist delivered BIs are feasible and are effective at changing alcohol-related injuries/problems9 or alcohol consumption among problem drinkers.66 Only one study has examined a computerized delivery of an alcohol prevention program for adolescents in the ED;67 this prevention study showed promise among high risk older adolescents, but was not based on the principles of Motivational Interviewing.68 Many, but not all BIs in ED settings have incorporated or adapted principles of motivational interviewing; these approaches are particularly well suited to adolescents because they emphasize autonomy in making decisions to change and are based on harm reduction principles.50, 69 BIs68, 70–75 aim to change attitudes, self-efficacy, and readiness to change as these variables have been identified as precursors to behavior change.

To date, interventions for youth violence that are brief and limited to the ED visit are lacking and untested in any format (computer or therapist). Instead, ED or hospital-initiated violence interventions have focused exclusively on adolescents presenting with an assault related injur, and thus likely further along the problem severity continuum; these interventions have generally been multi-session and involved case management7, 8, 62. Although some researchers have suggested that the ED is not an appropriate setting for youth violence interventions,76 it is unknown how screening and BI would be received by adolescents, parents, and medical staff during an ED visit. Finally, there has been no BI for alcohol or violence that involved universal screening regardless of chief complaint.

Our study addresses the issue of the acceptability of ED-based interventions for alcohol and violence among inner city adolescents, regardless of their reason for seeking ED care. No prior work has demonstrated that high risk teens during an ED stay would engage and complete an intervention on the combined topic of alcohol and violence, on the computer or with a therapist. The high participation rates, as well as the data on completion of the intervention we feel suggest that this type of intervention with both delivery modes is possible in this setting, a question which had not been answered in prior research. Although adolescents responded most positively to the therapist condition, the computer condition was also well received. Screening and interventions were feasible, with most adolescents completing the computerized screening and interventions without RA assistance and prior to ED discharge with little or no impact on clinical care. Taken together these data supports the acceptability and feasibility of universal computerized screening, as well as the concept that intervention that focus on more then one risk factor, both alcohol and violence, are possible in an inner city ED.

Understanding the appeal that BI’s have developmentally with adolescents, it should be noted that the sections, “Reviewing the reasons to change drinking and fighting”, and “Role plays” were the most well “liked” elements of the interventions, with 30% adolescents rating both these sections “extremely helpful”. A recent study determined that the motivational interviewing component (i.e., decisional balance – an examination of costs of staying the same and the benefits/reasons for change) of an alcohol BI was more effective than personalized feedback alone among young adults (ages 18–24) in the ED.77

Given the lack of current knowledge of BI for multiple risk behaviors among adolescents, particularly for behaviors as seemingly complex as alcohol and violence, initial outcomes of the SafERteens intervention, a motivational interviewing based BI, show promise. Analyses comparing the therapist BI and computer BI conditions with the control condition show significant positive changes in alcohol and violence attitudes, and self-efficacy for avoiding fighting at 3-month follow-up. In addition, improved self-efficacy for avoiding alcohol use was observed in the therapist BI condition. Although modest, the effect size demonstrated by these single session BIs is comparable to the range noted in recent prevention literature for both attitudes and behavioral outcomes (0.10- 0.36)55–59, 78 and to that noted in a prior ED-based alcohol BI study of adolescents for alcohol related problems (0.23).9 Although the present study focused on attitudes and self-efficacy as primary outcomes, prior ED studies demonstrate that alcohol self-efficacy is associated with drinking levels over time.70, 79, 80 Similarly, school-based studies41, 81 show that alcohol attitudes and self-efficacy are related to future alcohol use and that violence attitudes and self-efficacy are related to violent behavior.82

Although theoretically BIs should increase readiness to change related to alcohol use,68 research demonstrating the moderating impact of BIs on readiness to change is generally lacking in the literature,79, 80, 83 particularly for adolescents.70 In our study, the null findings for readiness to change may be explained by the study’s prevention focus, which was reflected in the low level of alcohol consumption required for study eligibility, or by the single Likert item used to assess this concept. For instance, many participants reporting drinking no alcohol during 3-month follow-up indicated they were in the “precontemplation” stage of change (i.e., never think about my drinking). To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the construct of readiness to change for violence. Thus, our lack of findings may reflect inappropriate application of the readiness to change concept toward violence, or reflect potential limitations in our single assessment item.

The intervention results presented here are novel for several reasons. First, the intervention addressed two related but distinct behaviors, alcohol use violence, with initial positive findings for attitudes and self-efficacy of both behaviors. The novelty of delivering BIs targeting multiple risk behaviors is analogous to where research on BIs for alcohol problems was 20 years ago. Previously, selective prevention for adolescents’ risky drinking was noticeably lacking in the alcohol field, mostly consisting of school-based multi-session prevention programs or community-based health promotion campaigns. It was often assumed that intervention effectiveness was directly related to dose. BIs for reducing alcohol use and consequences among adults have been found to be as effective as more extensive multi-session treatment.84–87 This study is also the first to evaluate the effect of a single session BI for violence in the ED. Prior ED-based BIs, using non-MI approaches for violence, have provided adolescents with tours of ED trauma units88, 89 or taped interviews with victims of violence.90 One advantage of individual over group approaches is that interventions designed to reduce delinquency and other problem behaviors can actually increase these problems when at-risk adolescents are grouped together.91

Data from this study demonstrating initial positive findings for the computer intervention are novel. In addition, the findings presented here were very similar for both therapist and computer conditions. If future analyses demonstrate effectiveness at changing behaviors, computerized BIs could have enormous potential for widespread dissemination with minimal ED staff or therapist time. Only one prior study has examined an alcohol intervention delivered completely by a computer in the ED.67 Further, in the present study, the therapist condition utilized a computer in a novel, interactive way, adding structure and standardizing the therapist condition to inherently increase fidelity, without fully scripting the therapist intervention. Although others have recommended the use of highly structured BIs, using workbooks and/or other means (e.g. computers) to standardize content and delivery and prompt trained staff,84, 92 few ED trials have used these methods. Using a computer to standardize the structure of a therapist BI is a feasible delivery strategy that could be applied to ED-based BIs for other content areas and age ranges.

Limitations

Although attitudes, self-efficacy and readiness to change are important markers of initial and immediate intervention effects, the more compelling test of intervention effectiveness on behavior change will be evaluated upon completion of the SafERteens randomized controlled trial, including 12-month outcomes. This evaluation of the intervention has been conducted within the parameters of a research protocol, and further research will needed to understand if and how to best translate findings to clinical practice without the research protocol framework if ongoing evaluations are positive. Because adolescents presenting with acute suicidal ideation or attempt and sexual assault, or those seeking care on the overnight shift were excluded from the study, findings do not generalize to these patients. In addition, our sample reflected the composition of the study ED; future studies are needed to examine effects with other samples, including Hispanic adolescents. Although behaviors assessed in this study were obtained via self-report, recent reviews have concluded that self-report of risk behaviors (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, drug use, and violence) among adolescent and young adults demonstrate good reliability and validity,93–97 and adolescents and young adults are more likely to report risky behaviors using computerized surveys and when privacy/confidentiality is assured, as was done in this study, which had a NIH Certificate of Confidentiality.28, 97–100 Replication is required given that our full assessment contained questions from several separate previously validated instruments. Finally, although a strength of this study is its focus on an inner city ED, a logical focus for violence prevention initiatives, the findings may not generalize to suburban or rural EDs.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that computerized screening and delivery of a single session BI for alcohol and violence to adolescents in the ED is feasible and well received, regardless of delivery mechanism (therapist or computer). The SafERteens interventions utilized technology to tailor the interventions to the specific risk factors of the adolescent and found significant effects at post-test and 3-months following the ED visit in attitudes and self-efficacy related to alcohol and violence with effect sizes comparable to prior successful interventions. These preliminary results of the SafERteens intervention, in both the computer and therapist conditions, show the potential of technology to aid in the cost effective delivery of health interventions in busy clinical settings. Future analyses will evaluate the effectiveness of the SafERteen intervention on behavior change at 3-, 6-, and 12-months.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Cunningham had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project was supported by a grant (#014889) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). We would like to thank project staff Bianca Burch, Yvonne Madden, Tiffany Phelps, Carrie Smolenski, and Annette Solomon for their work on the project; also, we would like to thank Pat Bergeron for administrative assistance and Linping Duan for statistical support. Finally, special thanks are owed to the patients and medical staff at Hurley Medical Center for their support of this project.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics & U.S. Health Care Financing Administration. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification: ICD-9-CM. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Adolescent Health Information Center (NAHIC) [Accessed March 28, 2008];fact sheet on mortality: Adolescents and young adults. 2006 Available at: http://nahic.ucsf.edu/download.php?f=/downloads/UnintInjury.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS Leading Causes of Death Reports, 1999–2002. [Accessed December 21, 2005]. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Posner JC, Hawkins LA, Garcia-Espana F, et al. A randomized, clinical trial of a home safety intervention based in an emergency department setting. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1603–1608. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston BD, Rivara FP, Droesch RM, et al. Behavior change counseling in the emergency department to reduce injury risk: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002 Aug;110(2 Pt 1):267–274. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maio RF, Shope JT, Blow FC, et al. Adolescent injury in the emergency department: opportunity for alcohol interventions? Ann Emerg Med. 2000 Mar;35(3):252–257. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zun LS, Downey L, Rosen J. The effectiveness of an ED-based violence prevention program. Am J Emerg Med. 2006 Jan;24(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng TL, Wright JL, Markakis D, et al. Randomized trial of a case management program for assault-injured youth. Ped Emerg Care. 2008;24(3):130–136. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999 Dec;67(6):989–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swahn MH, Donovan JE. Alcohol and violence: Comparison of the psychosocial correlates of adolescent involvement in alcohol-related physical fighting versus other physical fighting. Addict Behav. 2006 Mar 6; doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walton MA, Cunningham R, Goldstein AL, et al. Rates and Correlates of Violent Behaviors among Adolescents Treated in an Urban ED. J Adolesc Health. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.005. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics. 2003 May;111(5 Pt 1):949–955. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991 Dec;12(8):597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Adolescent problem drinking: stability of psychosocial and behavioral correlates across a generation. J Stud Alcohol. 1999 May;60(3):352–361. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins JD, Herenkohl T, Farrington DP, et al. A review of predictors of youth violence. In: Loeber R, Arrington DP, editors. Serious & Violence Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 106–146. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swahn MH, Donovan JE. Correlates and predictors of violent behavior among adolescent drinkers. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Jun;34(6):480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White HR, Xie M, Thompson W, et al. Psychopathology as a predictor of adolescent drug use trajectories. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001 Sep;15(3):210–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, et al. Developmental associations between substance use and violence. Dev Psychopathol. 1999 Fall;11(4):785–803. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Bree MB, Pickworth WB. Risk factors predicting changes in marijuana involvement in teenagers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;62(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swahn MH, Simon TR, Hammig BJ, et al. Alcohol-consumption behaviors and risk for physical fighting and injuries among adolescent drinkers. Addict Behav. 2004 Jul;29(5):959–963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer RD, Swahn MH. Binge drinking and violence. JAMA. 2005 Aug 3;294(5):616–618. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, et al. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002 Nov;59(11):1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lessem JM, Hopfer CJ, Haberstick BC, et al. Relationship between adolescent marijuana use and young adult illicit drug use. Behavior genetics. 2006 Jul;36(4):498–506. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Youth Violence, Prevention 2000. Centers for Disease Control (CDC); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue Y, Zimmerman M, Cunningham R. Longitudinal Relationship between Alcohol Use and Violent Behavior among Urban African American Youths from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood. Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147827. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzger DS, Koblin B, Turner C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 Jul 15;152(2):99–106. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, et al. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998 May 8;280(5365):867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy DA, Durako S, Muenz LR, et al. Marijuana use among HIV-positive and high-risk adolescents: a comparison of self-report through audio computer-assisted self-administered interviewing and urinalysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 Nov 1;152(9):805–813. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris K, Florey F, Tabor J, et al. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design [WWW document] [Accessed 2008, May 21]; Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 31.Zun LS, Downey L, Rosen J. Who are the young victims of violence? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005 Sep;21(9):568–573. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000177195.45537.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed November 4, 2007]. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbss. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brener ND, Collins JL, Kann L, et al. Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:575–580. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, et al. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002 Oct;31(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Sep 14;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Alcohol use disorders identification test: factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002 Feb;26(2):223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Secondary school students. Vol. 1. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006. NIH Publication No. 07-6205. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, et al. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999 Jun;153(6):591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, et al. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003 Jan;27(1):67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000046598.59317.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jelalian E, Alday S, Spirito A, et al. Adolescent motor vehicle crashes: the relationship between behavioral factors and self-reported injury. J Adolesc Health. 2000 Aug;27(2):84–93. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Botvin GJ, Baker E, Filazzola AD, et al. A cognitive-behavioral approach to substance abuse prevention: one-year follow-up. Addict Behav. 1990;15(1):47–63. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90006-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Funk JB, Elliott R, Urman ML, et al. The Attitudes Towards Violence Scale: A Measure for Adolescents. J Interpers Violence. 1999 November 1;14(11):1123–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belgrave FZ, Reed MC, Plybon LE, et al. The impact of a culturally enhanced drug prevention program on drug and alcohol refusal efficacy among urban African American girls. J Drug Educ. 2004;34(3):267–279. doi: 10.2190/H40Y-D098-GCFA-EL74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bosworth K, Espelage D. Teen Conflict Survey. Bloomington, IN: Center for Adolescent Studies, Indiana University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaBrie JW, Quinlan T, Schiffman JE, et al. Performance of alcohol and safer sex change rulers compared with readiness to change questionnaires. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005 Mar;19(1):112–115. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, et al. Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: Where are the methods? Ann Emerg Med. 1996 Mar;27(3):305–308. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maio RF, Shope JT, Blow FC, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of an Emergency Department-based Interactive Computer Program to Prevent Alcohol Misuse among Injured Adolescents. Paper presented at: Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting; May 29-June 1, 2003; Boston, MA. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shope JT, Copeland LA, Maharg R, et al. Effectiveness of a high school alcohol misuse prevention program. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996 Aug;20(5):791–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999 Oct;230(4):473–480. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. discussion 480–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, et al. Motivational enhancement of alcohol-involved adolescents. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, Alcohol and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Interventions. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 145–182. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: The Guilford Press; 1991. Motivational Interviewing. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller WR, Sanchez VC. Motivating young adults for treatment and lifestyle change. In: Howard GS, Nathan PE, editors. Alcohol Use and Misuse by Young Adults. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rundall TG, Bruvold WH. A meta-analysis of school-based smoking and alcohol use prevention programs. Health Educ Q. 1988 Fall;15(3):317–334. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White D, Pitts M. Educating young people about drugs: a systematic review. Addiction. 1998 Oct;93(10):1475–1487. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931014754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cuijpers P. Effective ingredients of school-based drug prevention programs. A systematic review. Addict Behav. 2002 Nov-Dec;27(6):1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farrington DP. The effectiveness of school-based violence prevention programs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002 Aug;156(8):748–749. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cooper WO, Lutenbacher M, Faccia K. Components of effective youth violence prevention programs for 7- to 14-year-olds. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Nov;154(11):1134–1139. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.11.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gottfredson DC, Wilson DB. Characteristics of effective school-based substance abuse prevention. Prev Sci. 2003 Mar;4(1):27–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1021782710278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States Surveillance Summaries. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed June 9, 2006, 2006]. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbss/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooper C, Eslinger DM, Stolley PD. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J Trauma. 2006 Sep;61(3):534–540. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Havard A, Shakeshaft A, Sanson-Fisher R. Systematic review and meta-analyses of strategies targeting alcohol problems in emergency departments: interventions reduce alcohol-related injuries. Addiction. 2008 Mar;103(3):368–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02072.x. discussion 377–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nilsen P, Baird J, Mello MJ, et al. A systematic review of emergency care brief alcohol interventions for injury patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35(2):184–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barnett NP, Monti PM, Spirito A, et al. Alcohol use and related harm among older adolescents treated in an emergency department: the importance of alcohol status and college status. J Stud Alcohol. 2003 May;64(3):342–349. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004 Sep;145(3):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maio RF, Shope JT, Blow FC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an emergency department-based interactive computer program to prevent alcohol misuse among injured adolescents. Ann Emerg Med. 2005 Apr;45(4):420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baer JS, Peterson PL. Adolescents and young adults. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 320–332. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA. Adolescents, Alcohol and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Interventions. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Hum Dec Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In: Albarracin D, Johnson B, Zanna M, editors. The handbook of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Becker M. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:324–437. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984 Spring;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dowd MD. Consequences of violence. Premature death, violence recidivism, and violent criminality. Pediatric clinics of North America. 1998 Apr;45(2):333–340. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, et al. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007 Aug;102(8):1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mytton JA, DiGuiseppi C, Gough DA, et al. School-based violence prevention programs: systematic review of secondary prevention trials. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002 Aug;156(8):752–762. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, et al. Correlates of violence history among injured patients in an urban emergency department: gender, substance use, and depression. J Addict Dis. 2007;26(3):61–75. doi: 10.1300/J069v26n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bazargan-Hejazi S, Bing E, Bazargan M, et al. Evaluation of a brief intervention in an inner-city emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2005 Jul;46(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barkin SL, Smith KS, DuRant RH. Social skills and attitudes associated with substance use behaviors among young adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2002 Jun;30(6):448–454. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bosworth K, Espelage DL, DuBay T, et al. A preliminary evaluation of a multimedia violence prevention program for early adolescence. Am J Hth Bhvr. 2000;24(4):268–280. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Neumann T, Neuner B, Weiss-Gerlach E, et al. The Effect of Computerized Tailored Brief Advice on At-risk Drinking in Subcritically Injured Trauma Patients. J Trauma. 2006 Oct;61(4):805–814. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196399.29893.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barry KL. Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies for Substance Abuse. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, et al. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002 Mar;97(3):279–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993 Mar;88(3):315–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, et al. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dearing B, Caston RJ, Babin J. The impact of a hospital based educational program on adolescent attitudes toward drinking and driving. J Drug Educ. 1991;21(4):349–359. doi: 10.2190/6C1R-MB1K-6WKA-M1VG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McMahon J, Harris C, Safi C, et al. Impact of emergency department-based violence prevention program on adolescents’ attitudes and beliefs toward violence: VIP (Violence Is Preventable) Tour (Abstract 161) Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:S42. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tucker JB, Barone JE, Stewart J, et al. Violence prevention: reaching adolescents with the message. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999 Dec;15(6):436–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Biglan A, Brennan PA, Foster SL, et al. Helping adolescents at risk: Prevention of multiple problem behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. The Impact of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral for Treatment on Emergency Department Patients’ Alcohol Use. AnnEmergMed. 2007;50(6):699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gray TA, Wish ED. Substance Abuse Need for Treatment among Arrestees (SANTA) in Maryland. College Park, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. The self-report method of measuring delinquency and crime. In: Duffee D, editor. Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice: Criminal Justice 2000. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2000. pp. 33–83. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Buchan BJ, MLD, Tims FM, et al. Cannabis use: consistency and validity of self-report, on-site urine testing and laboratory testing. Addiction. 2002 Dec;97 (Suppl 1):98–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dennis M, Titus JC, Diamond G, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) experiment: rationale, study design and analysis plans. Addiction. 2002 Dec;97 (Suppl 1):16–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Dec;33(6):436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wright SW, Norton VC, Dake AD, et al. Alcohol on campus: alcohol-related emergencies in undergraduate college students. South Med J. 1998 Oct;91(10):909–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Webb PM, Zimet GD, Fortenberry JD, et al. Comparability of a computer-assisted versus written method for collecting health behavior information from adolescent patients. J Adolesc Health. 1999 Jun;24(6):383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Harrison LD, Martin SS, Enev T, et al. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. Department of Health and Human Services Publication No. SMA 07-4249, Methodology Series M-7. [Google Scholar]