Abstract

The mechanism of growth of fibrils of the β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) was studied by means of a physics-based coarse-grained united-residue (UNRES) model and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. To identify the mechanism of monomer addition to an Aβ1–40 fibril, an unstructured monomer was placed at a 20 Å distance from a fibril template, and allowed to interact freely with it. The monomer was not biased towards the fibril conformation, by either the force field or the MD algorithm. By using a coarse-grained model with replica exchange MD, a longer time scale was accessible making it possible to observe how the monomers probe different binding modes during their search towards the fibril conformation. Although different assembly pathways were seen, they all follow a dock-lock mechanism, with two distinct locking stages, which is consistent with data from experiments on fibril elongation. Whereas these experiments have not been able to characterize the conformations populating the different stages, we have been able to describe these different stages explicitly by following free monomers as they dock onto a fibril template and adopt the fibril conformation; i.e., we describe fibril elongation step by step, at the molecular level. During the first stage of the assembly, “docking”, the monomer tries different conformations. After docking, the monomer is locked into the fibril through two different locking stages. In the first stage the monomer forms hydrogen bonds with the fibril template along one of the strands in a two-stranded β hairpin; in the second stage, hydrogen bonds are formed along the second strand, locking the monomer into the fibril structure. The data reveal a free-energy barrier separating the two locking stages. The importance of hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds in the stability of the Aβ fibril structure was examined by carrying out additional canonical MD simulations of oligomers with different numbers of chains (4 to 16 chains) with the fibril structure as the initial conformation. The data confirm that the structures are stabilized largely by hydrophobic interactions and show that the intermolecular hydrogen bonds are highly stable and contribute to the stability of the oligomers as well.

Keywords: amyloids, Aβ peptide, Alzheimer’s disease, hydrophobic interactions, UNRES force field, molecular dynamics

1. Introduction

Many diseases have been associated with deposits of amyloid plaques, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), type II diabetes, and spongiform encephalopathies. In the particular case of (AD), these plaques contain filamentous forms of a protein known as the β-amyloid peptide (Aβ)1,2. Oligomeric forms of this protein, both fibrilar3 as well as soluble nonfibrilar Aβ aggregates4, have been identified as the cause of AD. However, the mechanism(s) by which they may initiate the disease is still unclear5.

Great progress has been achieved in elucidating the 3D structure of amyloid fibrils6–12, and we now know that amyloid fibrils from different species share a characteristic motif, the cross-β structure, in which the polypeptide chains form extended β strands that align perpendicular to the axis of the fibril. Fibrils formed by the Alzheimer’s Aβ1–40 peptide have been studied extensively by Tycko and co-workers9,10,12. Based on constraints from solid state NMR, structural models of Aβ1–40 fibrils have been proposed10,12.

Despite progress in understanding the fibrilar state of Aβ, the mechanism by which small oligomers evolve into their fibrilar form or how these fibrils grow is not yet well understood13. In the laboratory, Aβ1–40 fibril formation takes as long as days14,15, and elongation proceeds by incorporating new monomers at a constant rate of approximately 0.3μm/minute (with a few milli-seconds per monomer incorporated)14. These time scales make simulations of fibril formation, or elongation, extremely challenging.

To overcome the time limitation, most all-atom studies have focused on small fragments of Aβ16–18. Although these studies17,18 have contributed greatly to our understanding of the transition that an unstructured monomer undergoes upon binding to a fibril, they might not reflect the full complexity of the complete Aβ1–40 system. Implicit-solvent all-atom simulations of elongation of Aβ1–40 have been carried out19 but, due to their high computational cost, these simulations could not describe the assembly of a completely unstructured and unbound monomer into a fibril template. Another approach has been the use of coarse-grained models, biased towards the desired conformation20,21 or simplified models in which the polypeptide chain is represented by a tube, and the interactions between amino acids are derived from geometry and symmetry considerations22. These models have the disadvantage that they might not reproduce the complexity of the true energy landscape.

In this work, we have adopted a coarse-grained united-residue (UNRES) model23,24 to partially surmount the time-scale problem. The advantage of UNRES over other coarse-grained force fields is that UNRES has been derived on the basis of physical principles. The energy terms are the result of averaging the less important degrees of freedom of the all-atom free energy of a protein and the solvent23. The force field ultimately has been parameterized to reproduce the free energy landscape of a small training protein, completely different from Aβ25–29. Therefore, the force field is not biased towards the Aβ fibril conformation. Moreover, UNRES has been shown to be able to carry out MD simulations of the folding of multichain systems within reasonable time, starting from completely unstructured conformations, and without using any information from the native structure of these systems24. Therefore, UNRES has been adopted to simulate the assembly of a free monomer onto a fibril template without imposing any type of restraint on the monomer. A description of the force field23 as well as details of the MD implementations24,30,31, can be found in sections S.6 and S.7 of the Supplement.

With the UNRES model, we carried out canonical molecular dynamics (MD) and replica exchange MD (REMD) simulations to: a) describe the ensemble of conformations explored by the isolated monomer of Aβ1–40; b) analyze the stability and energetics of small oligomers of Aβ1–40 with the structure that is characteristic of Aβ1–40 fibrils, and determine how their stability is related to the size of the oligomers; and c) study the elongation process of Aβ1–40 fibrils.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterizing the ensemble of isolated monomers

While oligomeric forms of Aβ adopt β-rich structures in the monomeric state, the peptide seems to adopt helical conformations32. Unfortunately, because Aβ has a high tendency to aggregate and eventually precipitate, it has not yet been possible to study the full-length peptide in water solution. Experiments on fragments of Aβ in water at low pH showed that the fragments have little regular structure33,34. To prevent aggregation, many experiments are carried out in a mixture of water and organic solvents, such as trifluoroethanol (TFE)35,36, micellar solutions37,38, or hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP)32,39. Under these conditions, the monomeric Aβ peptide shows substantial helical structure.

All-atom implicit solvent simulations40,41 showed that Aβ39 adopts random coil and helical conformations41, while Aβ40 and Aβ42 exist predominantly in two types of conformations, each one possessing significant amounts of either α or β-structure40. All-atom explicit solvent simulations also support the hypothesis that Aβ can adopt helical conformations as a monomer32.

The ability of Aβ to adopt both helical and β-sheet conformations is also supported by the fact that a helical intermediate has been observed during fibril assembly42,43. Furthermore, up to a certain degree, by stabilizing helical conformations, fibril formation is accelerated43, which suggests that the helical intermediate might facilitate the process42,43.

The foregoing results indicate that a model suitable for the study of Aβ amyloids should be able to capture an α-helical propensity at the monomer level as well as the formation of oligomeric structures with high β content. To test whether UNRES could capture the ability of monomers to adopt α-helical and β-sheet conformations, we carried out a set of 40 ns independent canonical MD simulations of an isolated monomer of Aβ1–40 at constant temperature (see section 4.1 for computational details).

2.1.1. Aβ1–40 populates three main clusters with α-helix or β-strand conformations

The conformations visited by the monomer were clustered based on their structures (see section 4.1). The three largest clusters were identified, accounting for 69% of the conformations. These three clusters also contained the conformations with the lowest energies, as calculated with the UNRES force field. The largest of these three, containing 56.5% of the conformations, corresponds to structures with high α-helical content (see Figure 1). The second and third largest clusters, accounting for 7.5% and 4.7% of the conformations, have β structures. Figure 1 shows the probability of occurrence of conformations populating the three largest clusters as a function of the UNRES potential energy of each cluster (see section 4.1). A representative conformation for each cluster is also shown.

Figure 1.

Probability of occurrence of conformations populating the three largest clusters as a function of the UNRES potential energy of the representative conformation. The representative conformation of a cluster is defined as that with the lowest RMSD from all other members of the cluster. The representative conformation for each cluster is shown, and the correspondence is indicated by arrows.

These results indicate that, at the monomer level, UNRES can reproduce the ability of Aβ1–40 to adopt helical and β-strand conformations. Furthermore, the UNRES force field, being a coarse-grained one, can facilitate a study of the behavior of large oligomers, a task that is still challenging with an all-atom force field, making UNRES a very good choice to study Aβ amyloids.

2.2. Stability of Aβ1–40 fibril conformation

In order to study fibril propagation, we want to determine the smallest system that can reproduce the interaction between a fibril and a free monomer. From solid state NMR studies, we know the structure of Aβ1–40 9,10,12, but we don’t know if a small section of a fibril will be stable by itself, or if it will produce the interactions of a full length fibril in the presence of an incoming monomer. In this section, we determine the size of the system needed to reproduce this interactions.

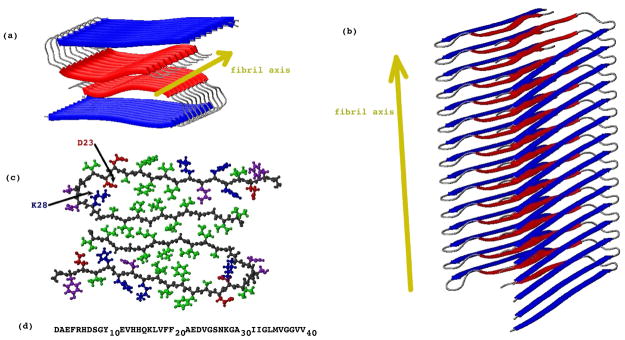

Solid state NMR studies9,10,12 of Aβ1–40 fibrils have shown that, in the fibrilar conformation, the peptide adopts the cross-β structure [Figure 2(a)44]. Each chain adopts a hairpin-like structure [Figure 2(c)], but lacking the hydrogen bonds of conventional anti-parallel β-sheets. These hairpins associate in pairs that lie in the same plane forming the double-hairpin structures of Figure 2(c). These double-hairpin structures form interplane parallel β-sheet-like hydrogen bonds with a similar pair of hairpins in a consecutive layer.

Figure 2.

Structural model for an Aβ1–40 fibril with the striated ribbon morphology. The Figure was produced with MolMol44, based on the coordinates provided by Robert Tycko for the structural model of Petkova et al.10. Residues 1-8 are omitted from the diagram because they were conformationally disordered in the NMR model10. (a) Axial view and (b) side view of the fibril. The fibril axis is indicated by a dark yellow arrow. N-terminal β strands are colored in blue, while C-terminal β strands are colored in red. The fibril is formed by layers of dimers, lying perpendicular to the fibril axis. (c) An all-atom representation of a dimer from a fibril layer. Hydrophobic, polar, negatively charged and positively charged side chains are colored in green, purple, red, and blue, respectively. (d) The sequence of Aβ1–40. Only residues 9-40 were used in the simulations of oligomers.

When describing the fibrilar structures, we will use the term layer to refer to the unit containing the dimer [Figure 2(c)], perpendicular to the fibril axis. The term semi-filament will be used used to refer to a stack of hydrogen-bonded monomers, parallel to the fibril axis. According to this terminology, a fibril can be seen as formed by two parallel semi-filaments, or by a stack of parallel layers.

From NMR experiments9,10, we know that Aβ1–40 fibrils are stabilized primarily by hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interaction. Specifically, residues L17, F19, A21, A30, I32, L34, and V36 create a hydrophobic cluster between the β-strands in each monomer [Figure 2(c)] and between the β-strands of one monomer and those of a monomer in a consecutive layer within each semi-filament. The structure is stabilized further by salt bridges between oppositely charged residues D23 and K28, within the same or consecutive layers45. At the interface between the two monomers in a given plane [Figure 2(c)], the structure is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions involving residues I31, M35, and V39. In-registry intermolecular hydrogen bonds comprising residues 10-22 and 30-40 are formed between consecutive layers9,10.

The question of whether small oligomer of Aβ40 could be stable in the fibrilar conformation has been studied by computer simulations21,45. Buchete et al.45 used molecular dynamics (MD) and all-atom force fields to study the behavior of a four-layer Aβ40 oligomer (i. e., an eight-chain oligomer), and showed that the system was stable during a 10 ns simulation. On the other hand, with a coarse-grained model, Fawzi et al.21 found that Aβ1–40 oligomers were stable only for systems with 8 layers (16 chains) or more.

In order to design our simulations, we needed to answer the following questions. Will the native structure of the Aβ40 oligomers be stable with the UNRES force field? How will the stability of the oligomers change when their size is changed? And finally, will the interactions with free monomer change when the size of the oligomer is altered? To answer these questions, we carried out canonical MD simulations with the UNRES force field, starting from the native conformation10, and allowing it to fluctuate freely (see section 4.2). Since NMR data indicated that residues 1-8 were conformationally disordered, and were omitted in the structural model10, in our simulations we used the Aβ9–40 segment, for which the coordinates are available.

2.2.1. Simulations of Aβ9–40 oligomers with different numbers of chains

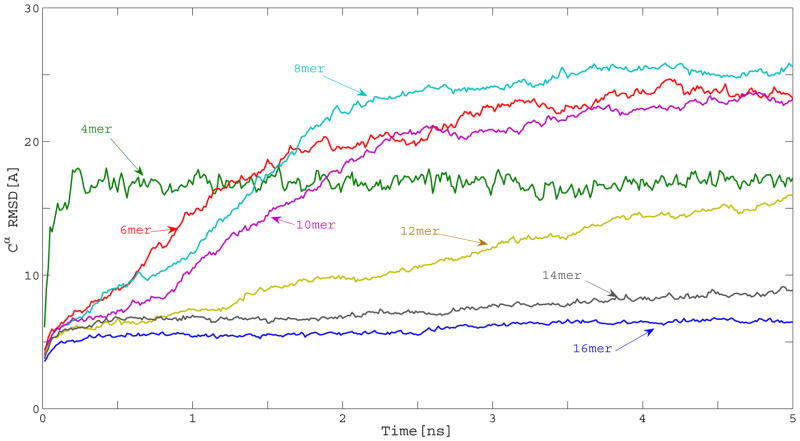

We studied systems with different numbers of layers, ranging from 2 to 8 (i. e., 4 to 16 chains). For each system, 8 independent 5 ns canonical MD trajectories, at 300 K, were simulated. To assess the extent of the structural changes during the simulations, we measured the Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) with respect to the initial conformation. The average RMSD (taken over all the trajectories with the same size) as a function of time for different sizes is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Average variation of the Cα RMSD with respect to the initial structure during constant temperature canonical MD simulations of Aβ9–40 oligomers with different numbers of chains per oligomer.

From Figure 3, it can be seen that, except for the 14- and 16-chain systems, the rest of the oligomers lose their initial structure during the simulation. Therefore, unless we decide to use systems as large as 14-chains, which will be too costly for simulating the free binding of monomers, we need to restrain the chains to the fibrilar conformation. We did not extend the simulations beyond 5 ns because that time scale was enough to observe the instability of the small oligomers. Snapshots along the pathway of representative trajectories illustrating the behavior of the different oligomers that do not retain their fibrilar structure are included in Figure S2 of the Supplement.

To find the reasons for the instability of the different oligomers, and to determine whether they could still act as fibril seeds for addition of a free monomer, we analyzed the energetics of the system. In sections 2.2.2 to 2.2.4 we examine the three main interactions stabilizing Aβ fibrils, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds and salt bridges.

2.2.2. Hydrophobic interactions increase linearly with the number of chains

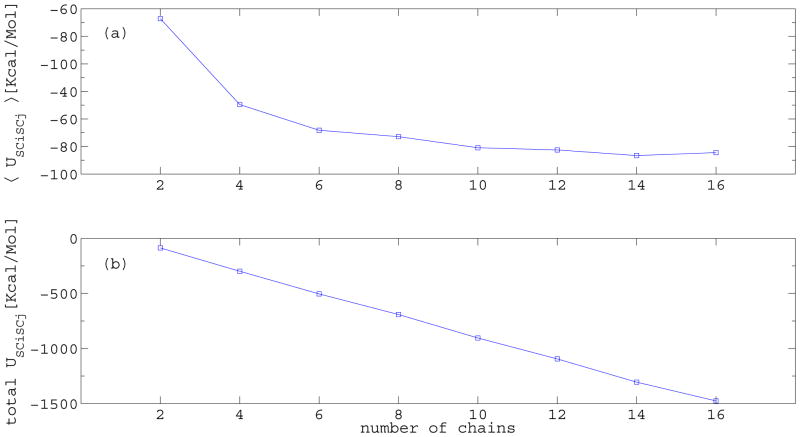

Our simulations (Figure 3) show that oligomers with 14 chains or larger are stable, but smaller oligomers are not. The reason is that, as the number of layers in the oligomer increases, the size of the hydrophobic core increases as well, and the nonpolar residues, especially in the center of the structure, are better buried, making the larger oligomers more stable. This becomes evident in Figure 4(a), which shows the average side chain-side chain energy, which in UNRES represents the hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions, averaged over the number of chains (〈USCiSCj〉), as a function of the oligomer size. As the size increases, the average contribution per chain to USCiSCj becomes larger, reaching a plateau around 14 chains.

Figure 4.

(a) Average side chain-side chain energy per chain (〈USCiSCj〉) and (b) total USCiSCj energy as a function of the number of chains.

The reason for the instability of the small oligomers of Aβ9–40 with the UNRES force field can be found in the competition between hydrophobic interactions and the electrostatic interactions, the dominant contribution to which comes from the term23. In UNRES, the energy term corresponds to the coupling between the dipole moments of two interacting peptide groups and the geometry of the backbone around them23. The particular conformation adopted by Aβ1–40 fibrils, is destabilized by this term, and a larger hydrophobic core is needed to compensate for it. A more detailed discussion about this effect is included in section S.3 of the Supplement.

It should be noted that the behavior of 〈USCiSCj〉 does not reflect a cooperative effect. As can be seen in Figure 4(b), the USCiSCj energy changes linearly with the number of layers. This means that, except for the first layer, which contributes only with the intra-layer hydrophobic interactions, adding a layer to a template always contributes with approximately the same USCiSCj energy, independent of the size of the systems. The edge affect, caused by the first layer not being able to hide the nonpolar residues from the solvent, becomes less important as the number of layers increases, and the hydrophobic core dominates, resulting in a more stable system (see section S.1 of the Supplement for a more detailed discussion).

The linear behavior of USCiSCj also implies that any layer in the fibrilar structure will have hydrophobic interactions with the layers adjacent to it. This means that, as far as the hydrophobic contributions are concerned, we need only a one-layer system to simulate the fibril-monomer interactions because the incoming monomer will interact only with the first layer at the surface of the fibril.

2.2.3. Interlayer hydrogen bonds are cooperative and stabilize Aβ9–40 oligomers

Even when the secondary structure of the monomers is lost, the hydrogen bonds between consecutive layers remain intact. This is expected since the stability of hydrogen bonds along each β-sheet is enhanced by their cooperative nature46, and UNRES is capable of capturing this effect23. The hydrogen bonds play an important role in stabilizing the structure of the larger Aβ oligomers, although not in the same way as the hydrophobic interactions. The fact that they make the stacking highly stable limits the conformational space available to the peptides in the stack. Being so stable, the hydrogen bonds act as restraints that restrict the conformational space of the hydrogen-bonded chains and reduce the conformational entropy of the unfolded state with respect to the folded state. The larger the system, the more limited the conformational space of its unfolded state and therefore, the more stable the system will be.

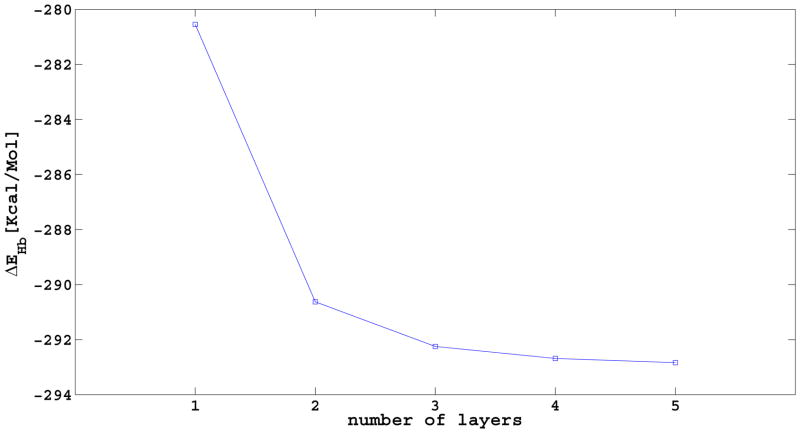

We also studied the presence of cooperativity in the hydrogen-bond interactions along the direction of the fibrils. Quantum mechanical calculations of small (six to seven residues) protein fragments, known to form amyloid fibrils6,11, have shown that hydrogen-bonding interactions are cooperative for the addition of one to three layers, becoming constant for later additions47,48. These results suggest that hydrogen-bond cooperativity might also be present in Aβ1–40. To test this hypothesis, we calculated the changes in UNRES hydrogen-bonding energy when adding a layer to a preexisting oligomer of n layers. This energy is obtained by computing the difference, ΔEHb(n), between the hydrogen-bonding energy of an oligomer with n and n + 1 layers [ΔEHb(n) = EHb(n + 1) − EHb(n)]. As can be seen from Figure 5, the values of ΔEHb(n) become increasingly negative with the addition of the first two layers, and remain almost constant for subsequent additions, in good agreement with the quantum mechanical calculations for a seven-residue peptide47. This result implies that, as for the hydrogen-bonding contributions, we need at least a two-layer or perhaps even a three-layer system to reproduce the monomer-fibril interactions. Having a larger system will contribute to the stability of the system, but will not make a difference in the monomer-fibril interactions.

Figure 5.

Difference in UNRES hydrogen-bonding energy, ΔEHb, when adding a layer to a preexisting oligomer of n layers. The value of ΔEHb(n) is obtained by computing the difference between the hydrogen-bonding energy of an oligomer with n and n + 1 layers. ΔEHb(n) = EHb(n + 1) − EHb(n)

2.2.4. Fibril elongation with the UNRES force field will not involve D23-K28 salt bridge formation

Finally, we examined the interactions between the oppositely charged residues D23 and K28, which are buried in the interior of the hydrophobic core in the NMR model, forming a salt bridge which should contribute to stabilize the structure45. However, the version of UNRES implemented in this study does not favor conformations with residues D and K in close interaction. The interactions between D23 and K28 are slightly repulsive in UNRES, helping to separate the N- and C-terminal strands of the monomers. Although D23-K28 repulsive interactions are not strong enough to destabilize the structure, the absence of an attractive force between them, an interaction that is important in the formation and stability of real Aβ1–40 fibrils10,15,45, hampers the stability of the oligomers. This problem is being addressed by introducing a new physics-based SC-SC potential energy into UNRES (work in progress).

Experimental studies suggest that the formation of the D23-K28 salt bridge might be the rate limiting step in Aβ1–40 fibril formation and elongation15. Simulations of Aβ monomers showed that D23 and K28 are initially solvated, and they have to overcome a high desolvation barrier to form a salt bridge49, supporting the hypothesis that the formation of the salt bridge is the rate limiting step, and therefore it must be an early event49. But it is also possible that other interactions guide the peptide towards the hairpin-like conformation and facilitate the formation of the salt bridge, which once formed, further stabilizes the structure. The repulsive interaction between D23 and K28 with the UNRES force field will in a sense account for the solvation penalty. If the formation of the salt bridge in the monomer is a necessary step for fibril elongation, we would not see the event. As we describe in sections 2.3.1 to 2.3.5, we do see fibril elongation with UNRES.

2.3. Fibril elongation

The polymerization process of Aβ fibril formation50–52 is characterized by a lag phase, during which a critical nucleus (seed) is formed, followed by a faster growth phase, during which free monomers are incorporated into the seed51. In vitro experiments have estimated that amyloid fibril formation takes days15, making computer simulations of the assembly of monomers into fibrils prohibited, even with a coarse-grained approach. However, the lag phase can be bypassed if a preformed seed is introduced15,51. There is evidence suggesting that fibrils grow by the addition of one monomer at a time53, and that the monomers adopt the conformation of the seed, propagating its structure54. Based on this information, we focused our studies on the process of addition of one monomer at a time onto a fibril.

It has been proposed that the addition of monomers into Aβ1–40 fibrils follows a two-state, “dock-lock” mechanism55,56. In the initial stage, the monomer is docked onto the fibrils, but it can easily dissociate; in the second stage, the monomer is locked into the fibril, i.e., it will rarely dissociate. Studies of deposition of Aβ1–40 monomers onto AD brain tissue and synthetic amyloid fibrils55 identified the transition between docked and locked states as the rate-limiting step. Results from a more recent experiment56 further revealed a more complex mechanism with two different locked states, the latest having an even slower dissociation rate. i.e., both locked states are very stable, but the final state has the highest stability. Although a mechanism has been proposed56, it has not yet been possible to obtain a detailed description of the conformations populating the assembly states.

We studied fibril elongation with the UNRES force field using the structural model of Petkova et al.10 as a fibril template. Simulating fibrils of real size would be extremely costly, even with a coarse-grained model. Based on the simulations reported in section 2.2.1, a 2-layer (4-chain) oligomer was the smallest system that could reasonably reproduce the monomer-fibril interactions; Hence we used templates of 4, 6 and 7 chains (i.e. 2, 3 and layers). From our studies of the stability of oligomers (section 2.2.1), we knew that template structures of these sizes were not stable with UNRES. Larger templates (14 chains or more) were stable, but it would have been computationally too expensive to use such systems for the simulation of monomer addition. This problem was surmounted by adding a term to the potential energy that stabilized the fibrilar conformation (see section 4.3 for details about this energy term), making the smaller templates stable as well. This energy term was applied to the chains of the fibril template, but not to the free monomer.

Preliminary simulations (data not shown) had shown that the monomer can easily become trapped in conformations with a number of energetically favorable contacts, that although not as stable as the fibrilar conformation (referred to as native here), take a long time to dissociate. To help overcome these situations, with minimum intrusion, we used replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) with a short range of temperatures, between 280 and 320 K (see section 4.3 for details about the implementation). Because the temperature of the replicas changes during a REMD simulation, the trajectories are disturbed, and the time evolution of the replicas does not reproduce folding pathways at constant temperature, but it gives a reasonable description of the order of the events during folding57. REMD has been used to study the folding process of proteins and RNA57–62, and different methods have been developed to obtain kinetic information from REMD simulation59,62,63. However, in our work we describe only the sequence of events, and we do not attempt to make estimates of the transition rates between those events or any other kinetic information.

2.3.1. The same binding mechanism is observed at both ends of the template

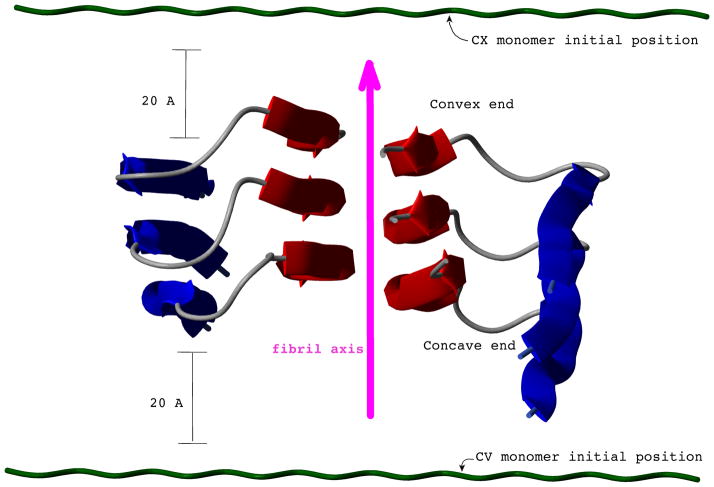

The β strands in the fibril do not lie exactly in a plane (see Figure 6), but the N-terminal strands are more exposed at one of the ends (the bottom end in Figure 6). Because of this asymmetry, it has been suggested that Aβ fibrils might grow in a unidirectional fashion19,21. Following the terminology adopted by Takeda and Klimov19, we refer to the exposed N-terminus as the concave (CV) end, and to the exposed C-terminus as the convex (CX) end. To test whether UNRES would reflect a preferred direction of growth, we carried out two sets of REMD simulations with the monomer in the extended conformation at a 20 Å distance from the surface of the template differing only in the initial position of the monomer, i.e., facing either the CV or CX end of the fibril (see Figure 6). For each set, we simulated 120, 20 ns long, REMD trajectories.

Figure 6.

Representation of the structure of an Aβ1–40 fibril. A magenta arrow indicates the direction of the fibril axis. Only three planes along the axis are shown. Due to the asymmetry of the structure on the convex (CX) end, the C-terminal strands (red) are more exposed than the N-terminal strands (blue). The two different initial positions (at the CV and CX ends) of the free monomer (dark green) are shown. In both initial conformations, the monomer is extended, and it is positioned at 20 Å from the closest fibril end.

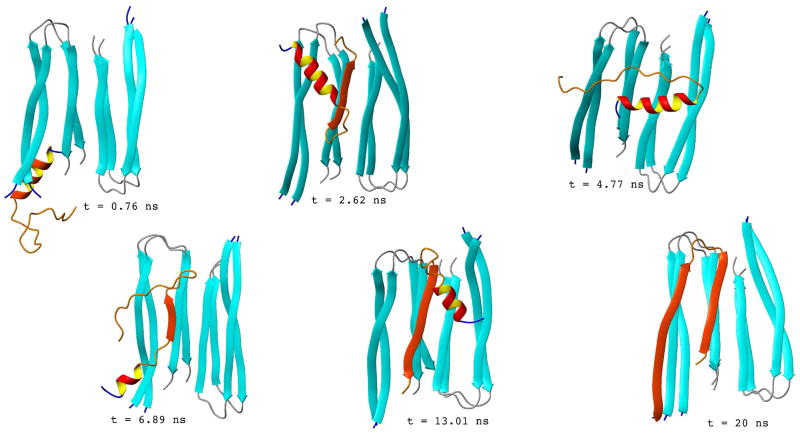

We found the same pattern in the binding mechanism at both the CV and CX ends of the template. Snapshots from two trajectories leading to successful monomer addition for a 2-layer template, are shown in Figures 7 (starting at the CV end) and 8 (starting at the CX end). In Figure 7, the first snapshot (t = 0.76 ns) shows the monomer before docking onto the template. As expected from our simulations of Aβ monomers, at this point the monomer adopts conformations with significant α-helical content. At t = 2.62 ns, the monomer has bound to the template with the wrong (antiparallel) orientation. At t = 4.77 ns, the monomer is free again. At t = 6.89 ns, it attempts to bind again in a nonnative conformation. Further reorientation leads to the conformation shown at t = 13.01 ns, with several native hydrogen bonds along the C-terminal strand. Finally, the N-terminal strand follows and also makes native hydrogen bonds, locking the monomer in the fibrilar conformation (t = 20 ns snapshot). Figure 8 shows a similar mechanism for a trajectory starting at the CX end. Initially the monomer attempts to form nonnative conformations (t = 0.27 ns and t = 1.45 ns) that are later disrupted (t = 3.76 ns). Native binding starts with the assembly of its N-terminus (t = 16.75 ns) and later propagates towards its C-terminus (t = 20 ns).

Figure 7.

Selected snapshots along a representative trajectory of a monomer binding to a 4-chain fibril are shown. The monomer is initially placed in the extended conformation, at 20 Å from the CV end of the template. The snapshot at t = 0.76 ns shows the monomer before docking onto the fibril in a conformation with significant α-helical content. At t = 2.62, the monomer binds forming an antiparallel β-strand along the C-terminus, while the N-terminus forms an α-helix. At t = 4.77 ns, the monomer is free from the template again. At t = 6.89 ns, the monomer attempts to bind again, but the conformation is still nonnative. The monomer rearranges its position, and at t = 13.01 ns, its C-terminus has bound with the native conformation, with the α-helix along the N-terminus still being present. The α-helix unfolds and the N-terminus also binds with the native conformation, locking the monomer into the fibrilar conformation, as shown in the t = 20 ns snapshot.

Figure 8.

Same as Figure 7, except that the monomer is initially placed in the extended conformation, at 20 Å from the CX end of the fibril. The snapshot at t = 0.05 ns shows the monomer before docking onto the fibril in a conformation with a certain α-helical content. The monomer makes several attempts to bind (t = 0.27 ns, t = 1.45 ns, and t = 3.76 ns), but none of these conformations are native, and the binding is disrupted. Native binding starts with the assembly of the N-terminal strand (t = 16.75 ns). The C-terminal strand follows, locking the monomer into the fibrilar conformation as shown in the t = 20 ns snapshot.

2.3.2. Monomer adds following a dock-lock mechanism with two distinct locking states

We now look closely at the hydrogen bonds formed between the monomer and the template, along the folding trajectories shown in Figures 7 and 8. We adopted the following criteria to classify the hydrogen bonds: a hydrogen bond between peptide groups with indices i and j was considered native if |i−j| ≤ 3, and nonnative otherwise. Figures 9(a) and 9 (b) show the number of native (NHB) and nonnative (nNHB) hydrogen bonds as a function of time for the trajectories shown in Figures 7 and 8, respectively. For both trajectories, we can distinguish three stages in the dock-lock mechanism. During the first (docking) stage, very few native hydrogen bonds are formed. The conformations adopted during this first stage are not very stable and, the monomer binds and unbinds several times (reflected in NHB and nNHB rising and going back to zero several times). In the second stage [starting at ≈10 ns in Figure 9(a) and ≈6.5 ns in Figure 9(b)], which corresponds to the first locking state, the monomer makes several native hydrogen bonds (NHB ≈10), locking only one of the strands, while the other strand is still free to move. The last stage corresponds to the second locking state [starting at ≈18 ns in Figure 9(a) and ≈19 ns in Figure 9(b)]. During this stage, the free strand makes the remaining native hydrogen bonds, and the monomer is fully locked in the fibrilar conformation. Once the monomer is locked into this conformation, it can itself serve as a template for subsequent monomer additions.

Figure 9.

The number of native and nonnative hydrogen bonds (NHB and nNHB) between monomer and template during a trajectory leading to a full addition starting from the CV end (a) and CX end (b).

This assembly mechanism is consistent with the results obtained from experiments of Aβ monomer deposition55,56. We have identified a docking stage, and more remarkably, the two different locking stages. From our simulations, it becomes evident that the first locking stage is a necessary step that, by locking one of the strands, limits the conformational space available to the free strand and facilitates the assembly of the rest of the peptide.

Nguyen et al. studied the elongation of fibrils formed by the Aβ16–22 fragment16. Interestingly, the authors found that the monomers bind by a dock-lock mechanism. However, presumably because this fragment assembles with a much simpler architecture, lacking the hairpin present in Aβ1–40, they see a single locking stage. Our simulations show that Aβ1–40 has a more complex mechanism with the docking stage followed by two different locking stages.

2.3.3. The second locking step is highly cooperative

In the second locking stage, once the still-free strand makes one or two native hydrogen bonds, these bonds quickly propagate along the rest of the strand. This is shown in Figures 9(a) and 9 (b) as the abrupt rise in NHB by the end of the simulation. It is also seen as a scarcely-populated region between the native basin (at ≈26 NHB) and at the region below 20 NHB in Figure S4 of the Supplement. This behavior indicates a cooperative binding. This cooperative binding has also been observed in simulations of the assembly of Aβ fragments17. However, these small fragments show a single locking stage. This single stage is similar to the second locking stage in Aβ1–40 binding.

2.3.4. Binding mechanism does not change with template size

The larger systems with 6- and 7-chain templates showed the same dock-lock mechanism as the 4-chain templates. Here too, the two locking states can be distinguished, the first one corresponding to the native binding of one of the strands, and the final locking state corresponding to the native binding of the second strand. Figures S5 and S6 in the Supplement show examples of trajectories for the 6- and 7-chain templates.

2.3.5. Simulations do not show a preferred fibril end for monomer binding

We adopted the following criteria to determine whether a trajectory resulted in fibril elongation. If, at the end of the simulation, the monomer has no hydrogen bonds with any of the chains in the template, it is considered undocked. If it has formed less than 10 native hydrogen bonds, it is considered a nonnative addition. If it has formed more than 10, but less than 20 native hydrogen bonds, we consider it a half addition. Finally, if it has formed at least 20 native hydrogen bonds with any of the chains on the fibril, we consider it a full addition. It should be noted that a half addition corresponds to a monomer in the first locking stage, and a full addition to a monomer in the second locking stage. The number of undocked, nonnative, half and full additions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of final conformations obtained from 120 REMD simulations

| 4-mer+1 | 6-mer+1 | 7-mer+1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From CV enda | From CX endb | From CX endc | From CX endd | |

| full additionse | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) |

| half additionsf | 14 (1) | 12 (4) | 6 (0) | 2 (1) |

| nonnativeg | 104(13) | 107(29) | 106(24) | 91(11) |

| undockedh | 0 | 0 | 7 | 26 |

Number of trajectories that resulted in full additions, half additions, nonnative binding or undocked monomer for the following systems,

a 4-chain template with the monomer initially positioned facing the CV end,

a 4-chain template with the monomer initially positioned facing the CX end,

as in b, but for a 6-chain template, and

as in b, but for a 7-chain template. Trajectories were classified as

full additions if, by the end of the simulation, the monomer has formed at least 20 native hydrogen bonds with any of the chains on the template,

half additions if the monomer has formed more than 10 but less than 20 native hydrogen bonds,

nonnative if the monomer has formed less that 10 native hydrogen bonds, and

undocked if the monomer has no hydrogen bonds with any of the chains in the template. The number of full and half additions and nonnative binding on the opposite end are indicated between parentheses

The data show that the binding can occur at both ends of the fibril (CV or CX). It is interesting that, on several occasions, binding occurred at the opposite end of the fibril, i.e., a monomer initially facing the CV end could bind to the CX end, and vice versa. The number of full and half additions and nonnative binding on the opposite end are indicated between parentheses. Although our data show a slightly larger number of half and full additions to the CV end than to the CX end, the numbers are too small to arrive at any conclusions about preferences at the ends. However, it is important to note that monomers can bind to both ends of the fibril.

3. Conclusions

A coarse-grained model, UNRES, has been used to study the stability of Aβ9–40 oligomers and the process of fibril growth. Using this approach, we successfully simulated the assembly of free monomers into fibril templates, providing insight into the conformational changes leading to Aβ fibril propagation.

Regarding the stability of oligomers, we found that hydrophobic interactions play an important role in stabilizing the structures, and that these interactions become more important as the size of the oligomer increases, approaching their maximum values at around 16 chains. However, taking into account certain limitations of the force field, we conclude that oligomers smaller than 16 chains might also be stable in the fibrilar conformation.

Our results also showed that the hydrogen bonds, formed between chains in consecutive layers, are extremely stable. These hydrogen bonds act as restraints that, by limiting the conformations that the hydrogen bonded chains can adopt, reduce the conformational entropy of the unfolded state, thereby increasing the stability of the folded state. For larger systems, this effect also becomes more important because more hydrogen bonded layers will have less energetically favorable states available.

Regarding the hydrogen bonds between consecutive layers, we also studied the increase in their stability when adding a new layer to a preformed oligomer. This was done by computing the differences in the hydrogen-bonding energy between oligomers of different sizes. The results indicate the presence of cooperativity in the interlayer hydrogen bonds when adding one to three layers. For further additions, the energy change becomes constant. The result is in agreement with classical and quantum mechanical calculations with a 7-amino-acid fragment of a fibril-forming peptide from the yeast prion, Sup3547.

Fibril elongation was studied by allowing a free monomer to interact with a fibril template. The simulations produced trajectories leading to nonnative and native binding (native meaning that the monomer binds, adopting the same conformation as the other chains in the template). By studying those trajectories that led to native binding, we observed that they followed a common dock-lock mechanism. During the docking stage, the monomer interacts with the template, often making nonnative hydrogen bonds that later break. The second stage, locking, can be further divided into two consecutive steps. First, the monomer makes native hydrogen bonds along one of the β-strands in the template, and at this point half of the peptide is bound to the template, while the other end can move freely. The final locking step is the native binding of the free end. This final step was highly cooperative, as indicated by the fact that, once one or two native hydrogen bonds are formed between the free end and the template, these hydrogen bonds quickly propagate along the rest of the peptide. This final step locks the monomer into the fibril template. Experiments on monomer deposition56 have indicated the presence of two locking states; however these experiments could not describe the conformations populating these two states. Based on our simulations, we have proposed a description of this mechanism at the molecular level.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. MD simulations of isolated monomers

A total of 40 independent canonical MD simulations of monomers were carried out at the constant temperature of 300 K, held constant with the Berendsen thermostat64, as described in previous work24. The simulations were started with the monomer in the extended conformation. The monomer was allowed to equilibrate for 20 ns. The following 20 ns were then used to analyze the structures explored by the system. For each of the 40 independent trajectories, conformations were stored every 150,000 steps, providing a total of 1,200 conformations among all the trajectories. These 1,200 conformations were clustered into families by means of the minimal-tree algorithm65,66 based on the Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) distances between conformations. A 5 Å RMSD clustering criterion was used. Representative conformations from the three largest clusters (accounting for 69 % of the conformations) are shown in Figure 1. The UNRES energy of a cluster is calculated as that of the conformation with the lowest energy in the cluster.

4.2. Stability of Aβ9–40 oligomers

The canonical MD simulations of Aβ9–40 oligomers were carried out at 300 K, using the Berendsen thermostat24,64, and the initial conformation was that of the structural model of Petkova et al.10, shown in Figure 2. The systems simulated were oligomers with an even number of chains (2, 4, 6, etc, i.e., complete layers) from 4 to 16 chains. The energies of these conformations were first minimized by carrying out 50 ps restrained canonical MD simulations (see section 4.3 for details on restraints used), after which the system was allowed to evolve freely for 5 ns.

4.3. Fibril elongation

Fibril elongation was examined by simulating the interaction between a monomer and a fibril template. The fibril template was composed of 4, 6 or 7 chains, with the conformation of the structural model of Petkova et al.10. Since systems of such sizes (4 to 7 chains) are not stable with the version of the UNRES force field used here, an additional term, URestr, was added to it to restrain the template to the fibrilar conformation. The energy is given by equation 1

| (1) |

where the index l runs over all the segments being restrained, wRestr is the weight of the term, set at 5 × 104 Kcal/mol, and Q(l) is given by equation 2

| (2) |

where di,j and are the current and native distances between the Cα atoms from amino acids i and j, and Ndistl is the total number of distances in segment l. Two types of segments were considered, intrachain and interchain segments. For intrachain segments, the indices i and j run over all the amino acids in the chain, with i < j. Interchain segments were considered between adjacent chains (i.e., between chain n and, chain n + 1 or chain n + 2). For interchain segments, the indices i and j run over all the amino acids in the corresponding chains.

For the simulations of fibril elongation, we used replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD)67,68. For each system, we had 120 independent trajectories starting from the same initial conformation but at different temperatures ranging between 280 and 320 K, with intervals of 10 K. Exchanges were attempted every 20,000 steps and each simulation was run for 20 ns. Between exchanges, the temperature was held constant with the Berendsen thermostat24,64. For templates consisting of 6 and 7 chains, the monomer was initially placed at the CX end of the fibril in the extended conformation and 20 Å apart from the end of the fibril. For the 4-chain templates two sets of 120 trajectories were simulated, with the monomer initially 20 Å apart from the CV and CX end, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM-14312), the National Science Foundation (MCB05-41633), and by the CCT Graduate Assistantship Program from Louisiana State University. This research was conducted by using the resources of (a) our 616-processor Beowulf cluster at Baker Laboratory of Chemistry, Cornell University, (b) the National Science Foundation Terascale Computing System at the Pittsburgh Supercomputer Center, (c) the Informatics Center of the Metropolitan Academic Network (IC MAN) in Gdańsk, and (d) the resources of the Center for Computation and Technology at Louisiana State University. We thank Dr. Robert Tycko for providing the atomic coordinates for the Aβ1–40 structural model.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in alzheimer disease and down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe D. The molecular pathology of alzheimers-disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorenzo A, Yuan M, Zhang Z, Paganetti P, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Mautino J, Vigo F, Sommer B, Yankner B. Amyloid β interacts with the amyloid precursor protein: a potential toxic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:460–464. doi: 10.1038/74833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh D, Klyubin I, Fadeeva J, Cullen W, Anwyl R, Wolfe M, Rowan M, DJ DS. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yankner B, Lu T. Amyloid β-protein toxicity and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800018200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson R, Sawaya M, Balbirnie M, Madsen A, Riekel C, Grothe R, Eisenberg D. Structure of the cross-β spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature. 2005;435:773–778. doi: 10.1038/nature03680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritter C, Maddelein M, Siemer A, Luhrs T, Ernst M, Meier B, Saupe S, Riek R. Correlation of structural elements and infectivity of the het-s prion. Nature. 2005;435:844–848. doi: 10.1038/nature03793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makin OS, Atkins E, Sikorski P, Johansson J, Serpell LC. Molecular basis for amyloid fibril formation and stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:315–320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406847102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tycko R. Molecular structure of amyloid fibrils: insights from solid-state NMR. Q Rev Biophys. 2006;39:1–55. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petkova AT, Yau W-M, Tycko R. Experimental Constraints on Quaternary Structure in Alzheimer’s-Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawaya M, Sambashivan S, Nelson R, Ivanova M, Sievers S, Apostol M, Thompson M, Balbirnie M, Wiltzius J, McFarlane H, Madsen AØ, Riekel C, Eisenberg D. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-β spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature. 2007;447:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R. Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18349–18354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chimon S, Shaibat MA, Jones CR, Calero DC, Aizezi B, Ishii Y. Evidence of fibril-like β-sheet structures in a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1157–1164. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ban T, Hoshino M, Takahashi S, Hamada D, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Goto Y. Direct Observation of A β Amyloid Fibril Growth and Inhibition. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sciarretta K, Gordon D, Petkova A, Tycko R, Meredith S. Aβ40-Lactam(D23/K28) Models a Conformation Highly Favorable for Nucleation of Amyloid. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6003–6014. doi: 10.1021/bi0474867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen PH, Li MS, Stock G, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Monomer adds to preformed structured oligomers of Aβ-peptides by a two-stage dock-lock mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(1):111–116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607440104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy G, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Dynamics of locking of peptides onto growing amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11948–11953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902473106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien E, Okamoto Y, Straub J, Brooks B, Thirumalai D. Thermodynamic Perspective on the Dock-Lock Growth Mechanism of Amyloid Fibrils. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:14421–14430. doi: 10.1021/jp9050098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeda T, Klimov D. Replica exchange simulations of the thermodynamics of Aβ fibril growth. Biophys J. 2009;96:442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malołepsza E, Boniecki M, Kolinski A, Piela L. Theoretical model of prion propagation: a misfolded protein induces misfolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(22):7835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409389102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawzi N, Okabe Y, Yap E, Head-Gordon T. Determining the Critical Nucleus and Mechanism of Fibril Elongation of the Alzheimer’s Aβ1-40 Peptide. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auer S, Dobson C, Vendruscolo M. Characterization of the nucleation barriers for protein aggregation and amyloid formation. HFSP J. 2007;1:137–146. doi: 10.2976/1.2760023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liwo A, Czaplewski C, Pillardy J, Scheraga HA. Cumulant-based expressions for the multibody terms for the correlation between local and electrostatic interactions in the united-residue force field. J Chem Phys. 2001;115:2323–2347. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rojas A, Liwo A, Scheraga H. Molecular dynamics with the united-residue force field: Ab initio folding simulations of multichain proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:293–309. doi: 10.1021/jp065810x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liwo A, Arlukowicz P, Ołdziej S, Czaplewski C, Makowski M, Scheraga HA. Optimization of the UNRES force field by hierarchical design of the potential-energy landscape. I: Tests of the approach using simple lattice protein models. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:16918–16933. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ołdziej S, Liwo A, Czaplewski C, Pillardy J, Scheraga HA. Optimization of the UNRES force field by hierarchical design of the potential-energy landscape: II. O3-lattice tests of the method with single proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:16934–16949. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ołdziej S, Ła̧giewka J, Liwo A, Czaplewski C, Chinchio M, Nanias M, Scheraga HA. Optimization of the UNRES force field by hierarchical design of the potential-energy landscape: III. Use of many proteins in optimization. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:16950–16959. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liwo A, Khalili M, Czaplewski C, Kalinowski S, Ołdziej S, Wachucik K, Scheraga H. Modification and optimization of the united-residue (UNRES) potential energy function for canonical simulations. I. Temperature dependence of the effective energy function and tests of the optimization method with single training proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:260–285. doi: 10.1021/jp065380a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Y, Xiao Y, Liwo A, Scheraga H. Exploring the parameter space of the coarse-grained UNRES force field by random search: selecting a transferable medium-resolution force field. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2127–2135. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalili M, Liwo A, Rakowski F, Grochowski P, Scheraga HA. Molecular dynamics with the united-residue (UNRES) model of polypeptide chains. I. Lagrange equations of motion and tests of numerical stability in the microcanonical mode. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:13785–13797. doi: 10.1021/jp058008o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khalili M, Liwo A, Jagielska A, Scheraga HA. Molecular dynamics with the united-residue (UNRES) model of polypeptide chains. II. Langevin and Berendsen-bath dynamics and tests on model α-helical systems. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:13798–13810. doi: 10.1021/jp058007w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomaselli S, Esposito V, Vangone P, van Nuland N, Bonvin A, Guerrini R, Tancredi T, Temussi P, Picone D. The α-to-β conformational transition of Alzheimer’s Aβ-(1-42) peptide in aqueous media is reversible: A step by step conformational analysis suggests the location of β conformation seeding. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:257–267. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JP, Stimson ER, Ghilardi JR, Mantyh PW, Lu YA, Felix AM, Llanos W, Behbin A, Cummings M. 1H NMR of Aβ Amyloid Peptide Congeners in Water Solution. Conformational Changes Correlate with Plaque Competence. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5191–5200. doi: 10.1021/bi00015a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lazo ND, Grant MA, Condron MC, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. On the nucleation of amyloid β-protein monomer folding. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1581–1596. doi: 10.1110/ps.041292205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrow CJ, Yasuda A, Kenny PTM, Zagorski MG. Solution conformations and aggregational properties of synthetic amyloid β-peptides of Alzheimer’s disease: analysis of circular dichroism spectra. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:1075–1093. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90106-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sticht H, Bayer P, Willbold D, Dames S, Hilbich C, Beyreuther K, Frank R, Rösch P. Structure of amyloid A4-(1-40)-peptide of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:293–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.293_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ. Solution structure of amyloid β-peptide (1-40) in a water-micelle environment. Is the membrane-spanning domain where we think it is? Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–11077. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao H, Jao S, Ma K, Zagorski M. Solution structures of micelle-bound amyloid β-(1-40) and β-(1-42) peptides of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:755–773. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crescenzi O, Tomaselli S, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, D’Ursi AM, Temussi PA, Picone D. Solution structure of the Alzheimer amyloid β-peptide (1-42) in an apolar microenvironment - Similarity with a virus fusion domain. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5642–5648. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang M, Teplow D. Amyloid β-protein monomer folding: free-energy surfaces reveal alloform-specific differences. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:450–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anand P, Nandel F, Hansmann U. The Alzheimer’s β amyloid (Aβ1–39) monomer in an implicit solvent. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:165102. doi: 10.1063/1.2907718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirkitadze MD, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Identification and characterization of key kinetic intermediates in amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:1103–1119. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fezoui Y, Teplow DB. Kinetic studies of amyloid β-protein fibril assembly. Differential effects of α-helix stabilization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36948–36954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. Molmol: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchete NV, Tycko R, Hummer G. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Protofilaments. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:804–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dannenberg J. The Importance of Cooperative Interactions and a Solid-State Paradigm to Proteins-What Peptide Chemists Can Learn from Molecular Crystals. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;72:227–73. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)72009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsemekhman K, Goldschmidt L, Eisenberg D, Baker D. Cooperative hydrogen bonding in amyloid formation. Prot Sci. 2007;16:761–764. doi: 10.1110/ps.062609607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plumley J, Dannenberg J. The Importance of Hydrogen Bonding between the Glutamine Side Chains to the Formation of Amyloid VQIVYK Parallel β-Sheets: An ONIOM DFT/AM1 Study. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1758–1759. doi: 10.1021/ja909690a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarus B, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Dynamics of asp23-lys28 salt-bridge formation in Aβ10–35 monomers. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(50):16159–16168. doi: 10.1021/ja064872y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lomakin A, Chung D, Benedek G, Kirschner D, Teplow D. On the nucleation and growth of amyloid β-protein fibrils: Detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1125–1129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harper J, Lansbury P., Jr Models of amyloid seeding in Alzheimer’s disease and scrapie: mechanistic truths and physiological consequences of the time-dependent solubility of amyloid proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:385–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naiki H, Gejyo F. Section II. Characterization of in Vitro Protein Deposition-C. Monitoring Aggregate Growth by Dye Binding-20. Kinetic Analysis of Amyloid Fibril Formation. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collins S, Douglass A, Vale R, Weissman J. Mechanism of prion propagation: Amyloid growth occurs by monomer addition. PLOS Biol. 2004;2:1582–1590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petkova A, Leapman R, Guo Z, Yau W, Mattson M, Tycko R. Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Esler W, Stimson E, Jennings J, Vinters H, Ghilardi J, Lee J, Mantyh P, Maggio J. Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid Propagation by a Template-Dependent Dock-Lock Mechanism. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6288–6295. doi: 10.1021/bi992933h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cannon M, Williams A, Wetzel R, Myszka D. Kinetic analysis of beta-amyloid fibril elongation. Anal Biochem. 2004;328:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.García AE, Onuchic JN. Folding a protein in a computer: an atomic description of the folding/unfolding of protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(24):13898–13903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335541100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rhee YM, Pande VS. Multiplexed-replica exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding simulation. Biophys J. 2003;84(2 Pt 1):775–786. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74897-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andrec M, Felts AK, Gallicchio E, Levy RM. Protein folding pathways from replica exchange simulations and a kinetic network model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(19):6801–6806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408970102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.García AE, Paschek D. Simulation of the pressure and temperature folding/unfolding equilibrium of a small RNA hairpin. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(3):815–817. doi: 10.1021/ja074191i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maisuradze GG, Senet P, Czaplewski C, Liwo A, Scheraga HA. Investigation of protein folding by coarse-grained molecular dynamics with the unres force field. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114(13):4471–4485. doi: 10.1021/jp9117776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tseng C, Yu C, Lee H. From laws of inference to protein folding dynamics. Physical Review E. 2010;82:021914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.021914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang S, Onuchic JN, García AE, Levine H. Folding time predictions from all-atom replica exchange simulations. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(3):756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Späth H. Cluster analysis algorithms for data reduction and classification of objects. Halsted Press; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ripoll DR, Liwo A, Scheraga HA. New developments of the electrostatically driven Monte Carlo method – Test on the membrane bound portion of melittin. Biopolymers. 1998;46:117–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199808)46:2<117::AID-BIP6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Czaplewski C, Kalinowski S, Ołdziej S, Liwo A, Scheraga H. Application of Multiplexed Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics to the UNRES Force Field: Tests with α and α + β Proteins. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;5:627–640. doi: 10.1021/ct800397z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.