Abstract

Purpose

Reliable measures are required for proper cost–utility analysis after critical care. No gold standard is available, but the EQ-5D health-related quality of life instrument (HRQoL) has been proposed. Our aim was to compare the EQ-5D with another utility measure, the 15D, after critical illness.

Methods

A total of 929 patients filled in both the EQ-5D and 15D HRQoL instruments 6 and 12 months after treatment at an intensive care or high-dependency unit. The difference in the medians and distributions of the scores of the instruments was tested with Wilcoxon signed-rank test and their association with Spearman rank correlation. Discriminatory power was compared by the ceiling effect and agreement between the instruments regarding the direction of the minimal clinically important change in the HRQoL scores between 6 and 12 months was tested with the McNemar-Bowker test and Cohen’s kappa.

Results

The utility scores produced by the instruments and their distributions were different. Agreement between the instruments was only moderate. The 15D appeared more sensitive than the EQ-5D both in terms of discriminatory power and responsiveness to clinically important change.

Conclusion

The agreement between the two utility measures was only moderate. The choice of the instrument may have a substantial effect on cost-utility results. Our results suggest that the 15D performs well after critical illness, but further large cohort studies comparing different utility instruments in this patient population are warranted before the gold standard for utility measurement can be announced.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00134-010-1979-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: EQ-5D, 15D, Intensive care, Quality of life, Sensitivity, Responsiveness

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is an important patient-reported outcome after critical illness. In the intensive care context, several generic profile instruments, such as the SF-36 [1], the Sickness Impact Profile [2], and the Nottingham Health Profile [3], have been used. Also, the EQ-5D, a generic utility instrument enabling the calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and allowing the comparison of the cost-utility of interventions across different medical specialities, has been used [4–8]. Although no HRQoL instrument can claim to be the gold standard, the 2002 Brussels Roundtable Consensus meeting recommended the SF-36 and EQ-5D as the preferred HRQoL instruments in the critical care setting [9], but at the same time encouraged further methodological research and instrument design.

There is still an evident lack of comparisons between utility instruments in the critical care setting. The RAND-36 (SF-36) and the EQ-5D have been compared, and the former turned out to have slightly more discriminatory power [10]. However, the EQ-5D is currently the most widely used utility instrument worldwide for the calculation of QALYs [11]. Thus, it seemed appropriate to choose it in this study as the comparator to the 15D, which is the most frequently used utility instrument in Finland, although a possibility to generate a utility score (SF-6D) also from the SF-36 data has been introduced [12]. The 15D and EQ-5D have previously been compared in a number of other populations and patient groups [13–15], but not in critical care.

Materials and methods

Patients

The data were collected prospectively in the Helsinki University Hospital between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2004. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the patients. The study population consisted of 3,600 patients treated in two intensive care (ICU) and three high-dependency units (HDU).

HRQoL instruments

The EQ-5D and 15D were mailed to patients alive and with a known address 6 and 12 months after admission to the ICU or HDU together with an accompanying letter and an informed consent form. The patients were asked to return the questionnaires and the consent in a prepaid envelope. In case of non-response, one reminder was sent. Possible readmissions after the index admission did not start a new follow-up.

The EQ-5D consists of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. Each dimension is divided into three levels: no problems, some problems and severe problems. Instead of the Finnish VAS-based valuation algorithm used in some earlier Finnish critical care studies [5, 16], we used the UK time-trade-off (TTO) “tariff,” which is the most commonly used valuation system for the EQ-5D. According to it the utility scores range from −0.59 to 1, where 1 means full health and 0 stands for death. No health state can obtain a score between 0.88 and 0.99, and negative scores indicate health states worse than death [17]. The minimal clinically important difference (MID) for the EQ-5D TTO is about 0.08 [18].

The 15D consists of 15 dimensions: breathing, mental function, speech, vision, mobility, usual activity, vitality, hearing, eating, elimination, sleeping, distress, discomfort and symptoms, depression and sexual activity. Each dimension is divided into five levels from no problems to extreme problems. The utility scores of the 15D range from 0 to 1, with 1 being equivalent to full health and 0 to death [19]. The MID of the 15D has been estimated as 0.03 [20].

Statistical analysis

The mean and median scores of the two instruments at 6 months were calculated. The visual inspection of the distribution of the EQ-5D scores suggested that the use of classical parametric tests to compare the two sets of scores may not be appropriate. Therefore, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test the difference in medians and distributions. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to measure the association and a Bland-Altman plot to describe the agreement between the sets at 6 months. The discriminatory power of the instruments was explored by comparing the proportion of patients obtaining the ceiling score of 1 (ceiling effect). To analyse the agreement in the direction of change of the HRQoL scores between 6 and 12 months, a 3 × 3 matrix was constructed. The changes were classified according to MID as negative, if the change was ≤−0.08 and ≤−0.03, and positive, if the change was ≥0.08 and ≥0.03 for the EQ-5D and 15D, respectively. Other values were classified as unchanged. The McNemar-Bowker test was used to test whether the instruments give a similar picture of the changes (the matrix is symmetric) and Cohen’s kappa to test the agreement between the instruments. The p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Both the 6- and 12-month questionnaires were returned by 998 patients (38% of the 2,600 patients alive). However, 69 of the EQ-5D questionnaires were not filled in completely, leaving 929 patients for final analysis. Of them, 31% had been treated in an ICU and 69% in a HDU. For characteristics of the study population, see electronic material.

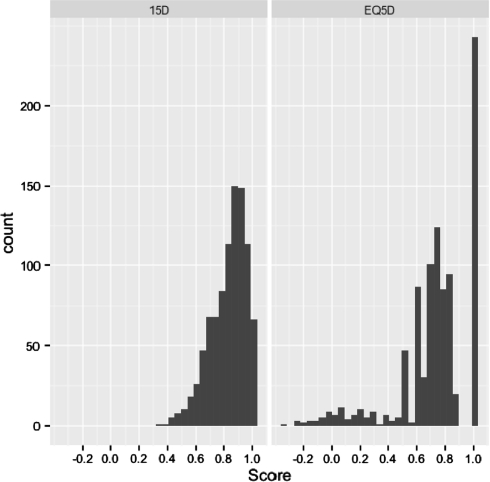

The distributions of the EQ-5D and 15D scores at 6 months are presented in Fig. 1. The distribution of the EQ-5D scores was wide, three-peaked and discontinuous, whereas that of the 15D was one-peaked and continuous. The rank correlation between the two sets of scores was 0.811 (p < 0.001). The mean (median) utilities at 6 months were 0.832 (0.859) and 0.731 (0.760) for the 15D and EQ-5D, respectively. The medians and distributions were different (p < 0.001) and the agreement between the sets poor (Bland-Altman plot in electronic material). The EQ-5D detected fewer health states than the 15D (at 6 months 79 vs. 767, at 12 months 70 vs. 745). Using the EQ-5D, 26% of patients had a ceiling score of 1 compared to 6% for the 15D. Regarding the clinically important change in the HRQoL scores between 6 and 12 months, the instruments had the same direction of change in 53% of the patients. The EQ-5D showed no change in 61% of patients, the 15D in 46%. Overall, the instruments gave a different picture of the changes (Bowker 53.9, p < 0.001), and the agreement between them was only fair (kappa 0.24, 95% CI 0.19, 0.29; (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The distributions of the EQ-5D and 15D scores at 6 months

Table 1.

The direction of the minimal clinically important change (MID) in the HRQoL scores between 6 and 12 months

| Change greater than the MID (0.08) in the EQ-5D score | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (%) | Unchanged (%) | Positive (%) | |||

| Change greater than the MID (0.03) in the 15D score | Negative (%) | 10.1 | 11.8 | 2.8 | 24.7 |

| Unchanged (%) | 6.4 | 32.4 | 7.2 | 46.0 | |

| Positive (%) | 1.6 | 16.8 | 10.9 | 29.3 | |

| Total (%) | 18.1 | 61.0 | 20.9 | 100.0 | |

Discussion

Patient-reported outcomes such as HRQoL have gained increased importance as measures of effectiveness of health care. Of the HRQoL instruments used in the assessment of critical care, only a few produce a utility score necessary for the calculation of QALYs. These include the EQ-5D and 15D, which we compared in this large cohort study. Regardless of the statistical test used, the agreement between the instruments was only moderate.

The main reason for this may be the wide, three-peaked and discontinuous distribution of the TTO-based EQ-5D scores with a high ceiling effect. Because of these features of the EQ-5D scores, classical methodology used for comparisons and evaluation of agreement between scores may not be applicable. The existence of negative utilities implies that HRQoL could be improved by dying, which is not logically congruent with the objectives of care, although from an ethical and economic point of view, a permanent non-independent health state may be worse than death. The distribution of the 15D scores (all positive values) was one-peaked and continuous and, importantly, only 6% of the patients evaluated their health state as perfect at 6 months after critical illness, indicating better discriminatory power of the 15D in minor health problems. The EQ-5D detected fewer health states and clinically important changes in HRQoL than the 15D. In this light, the 15D appeared more sensitive than the EQ-5D in terms of discriminatory power and responsiveness to clinically important change, although in the absence of a gold standard, it is not possible to say which instrument is “right.” In these respects our results agree with those obtained previously in a number of populations and patient groups [13–15].

Strengths and limitations

One strength is that HRQoL was measured simultaneously by both instruments. Our comparison revealed, therefore, differences and agreement regarding the instruments. In addition, the patient population was large (despite of the response rate of 38%). In general, the lack of baseline HRQoL scores may be seen as a limitation, but in the comparison of two instruments, as in our study, does not pose a problem. ICU and HDU patients were analysed together, but as only 34% of the sample belonged to the ICU subset, our results do not necessarily reveal how the instruments may work in comparison when applied exclusively to ICU patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the 15D may be more sensitive than the EQ-5D in terms of discriminatory power and responsiveness to clinically important change. The agreement between the EQ-5D and 15D utilities was only moderate. As utilities differ depending on the HRQoL instrument used, the results of the cost-utility studies in the critically ill are difficult to compare. In the future, large cohort studies are warranted to produce sufficient comparative evidence regarding utility measures, including the SF-6D and the 15D, before the gold standard for utility measurement may be announced.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Kaarlola A, Pettilä V, Kekki P. Quality of life 6 years after intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1294–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frick S, Uehlinger DE, Zürcher Zenklusen RM. Assessment of former ICU patients’ quality of life: comparison of different quality-of-life measures. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1405–1410. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1434-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamer C, Harboun M, Knani L, Moreau D, Tric L, LeGuillou J-L, Gasquet I, Moreau T. Quality of life after complicated elective surgery requiring intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1594–1601. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2260-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowdy D, Eid M, Sedrakyan A, Mendeze-Tellez P, Pronovost P, Herrdige M, Needham D. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaarlola A, Tallgren M, Pettilä V. Long term survival, quality of life and quality-adjusted life-years among critically ill elderly patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2116–2120. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227656.31911.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badia X, Diaz-Prieto A, Gorriz M, Herdman M, Torrado H, Farrero E, Cavanilles J. Using the EuroQol-5D to measure changes in quality of life 12 months after discharge from an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1901–1907. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granja C, Teixeira-Pinto A, Costa-Pereira A. Quality of life after intensive care—evaluation with EQ-5D questionnaire. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:898–907. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Thalanany MM, Hibbert CL, Truesdale A, Clemens F, Cooper N, Firmin RK, Elbourne D, for the CESAR trial collaboration Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaarlola A, Pettilä V, Kekki P. Performance of two measures of general health-related quality of life, the EQ-5D and the RAND-36 among critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2245–2252. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasanen P, Roine E, Sintonen H, Semberg-Konttinen V, Ryynanen OP, Roine R. Use of quality-adjusted life years for the estimation of effectiveness of health care: a systematic literature review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22:235–241. doi: 10.1017/S0266462306051051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21:271–292. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stavem K. Reliability, validity and responsiveness of two multiattribute utility measures in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:45–54. doi: 10.1023/A:1026475531996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saarni S, Härkänen T, Sintonen H, Suvisaari J, Koskinen S, Aromaa A, Lönnqvist J. The impact of 29 chronic conditions on health-related quality of life: a general population survey in Finland using 15D and EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1403–1414. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moock J, Kohlman T. Comparing preference-based quality-of-life measures: results from rehabilitation patients with musculoskeletal, cardiovascular or psychosomatic disorders. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:485–495. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson S, Ruokonen E, Varpula T, Ala-Kokko TI, Pettilä V. Long term outcome and quality-adjusted life years after severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c13ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35:1095–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sintonen H. The15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33:328–336. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sintonen H. Outcome measurement in acid-related diseases. PharmacoEconomics. 1994;5(Suppl. 3):17–26. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199400053-00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.