Abstract

Lesions obtained early in the course of multiple sclerosis (MS) have been studied immunocytochemically, and compared with the early stages of the experimental lesion induced in rats by the intraspinal injection of lipopolysaccharide. Large hemispheric or double hemispheric sections were examined from patients who had died in the course of acute or early relapsing multiple sclerosis. In MS patients exhibiting hypoxia-like lesions [Pattern III; Lucchinetti et al. Ann Neurol (2000) 47: 707–17], focal areas in the white matter showed mild oedema, microglial activation and mild axonal injury in the absence of overt demyelination. In such lesions T-cell infiltration was mild and restricted to the perivascular space. Myeloperoxidase and the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase were expressed primarily by microglia, and the activated form of these cells was associated with extracellular deposition of precipitated fibrin. In addition, these lesions showed up-regulation of proteins involved in tissue preconditioning. When active demyelination started, lesions were associated with massive T-cell infiltration and microglia and macrophages expressed all activation markers studied. Similar tissue alterations were found in rats in the pre-demyelinating stage of lesions induced by the focal injection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide into the spinal white matter. We suggest that the areas of microglial activation represent an early stage of tissue injury, which precedes the formation of hypoxia-like demyelinated plaques. The findings indicate that mechanisms associated with innate immunity may play a role in the formation of hypoxia-like demyelinating lesions in MS.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, lesion development, microglial activation, fibrin, innate immunity, lipopolysaccharide

Introduction

Inflammatory demyelinated plaques with partial axonal preservation and reactive gliosis are the hallmark of the pathology of multiple sclerosis (MS), particularly during the early (relapsing) stage of the disease (Prineas, 1985; Kutzelnigg et al., 2005). Most studies agree that active demyelination occurs on the background of an inflammatory reaction, including a perivenous accumulation of T- and B-lymphocytes, which also disperse into the CNS parenchyma (Traugott et al., 1983; Booss et al., 1983). Macrophages and activated microglia are adherent to partly damaged myelin sheaths and axons, suggesting a major role of these cells in the destructive process (Babinski, 1885; Prineas, 1985; Esiri and Reading, 1987; Ferguson et al., 1997; Trapp et al., 1998). Whether such inflammatory lesions are the initial event in tissue injury is, however, currently uncertain.

Recent studies that serially examined patients at the early (relapsing) stage of MS using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have demonstrated that magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) scans can reveal subtle focal changes in the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) at sites which days to weeks later develop into new T2-lesions (Filippi et al., 1998). In addition, parallel studies using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) suggest that subtle changes in axons may precede the formation of classical MS plaques (Narayanan et al., 1998). Because these changes occurred before obvious damage to the blood–brain barrier (as assessed by the leakage of gadolinium–DTPA), these tissue alterations seem to precede inflammation. Furthermore, study of the cerebral blood flow has also revealed changes well in advance of blood–brain barrier breakdown and of changes in the apparent diffusion coefficient (Wuerfel et al., 2004).

The reported data on the neuropathological nature of early MS lesions are conflicting. There has been good agreement that many MS plaques can form by confluence of small perivenous inflammatory demyelinating lesions (Rindfleisch, 1863; Dawson, 1916), and this has formally been proven in an exceptional case where an initial brain biopsy showed a perivenous inflammatory demyelinating lesion, but a second biopsy of the same patient, performed 76 days after the first, revealed a confluent demyelinated plaque at the same site (Bitsch et al., 1999). A similar pattern of perivenous, confluent lesions has also been described in a study of a large number of patients who died at a very early stage of the disease (Gay et al., 1997). However, another pathogenesis has been presented by Barnett and Prineas (2004), who have described early changes within plaques in terms of a field of microglial activation coupled with the apoptosis of oligodendrocytes. In fact, even in the Barnett and Prineas study some perivenous inflammation including T-cells was seen in the vicinity of these lesions, but the inflammatory infiltrates were not topographically related to the sites of tissue damage. Similarly, ‘(p)re-active’ lesions have been described in patients with progressive MS, which were defined as areas of microglial activation, perivascular accumulation of lymphocytes and tissue oedema in the absence of active demyelination (De Groot et al., 2001). These observations indicate that T-cells may not necessarily be responsible for triggering myelin destruction in some MS lesions.

We have recently described different patterns of demyelination in MS patients, which could at least partly explain the different interpretations outlined above (Lucchinetti et al., 2000). Pattern I and II lesions resemble the classical, confluent MS lesions (Lucchinetti et al., 2000), and they also resemble the lesions seen in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (Storch et al., 1998a). In the experimental models, such lesions indeed develop by confluence of perivenous demyelination. On the other hand, Pattern III lesions have some similarity with the lesions described by Barnett and Prineas (2004). Such lesions lacked an experimental model until it was suggested that the inflammatory demyelinating lesion induced by the focal injection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the spinal cord white matter caused demyelination that resembled the Pattern III lesion (Felts et al., 2005). Relatively little is known about the mechanisms involved in the early stage of Pattern III MS lesions or in the new experimental model of LPS-induced demyelination.

In this study we show that MS patients with Pattern III demyelination, and rats with LPS-induced demyelination, both exhibit similar tissue alterations in the NAWM, and these precede demyelination. A detailed characterization of these pre-demyelinating tissue alterations is the topic of this study.

Material and Methods

Human autopsy tissue

This study was performed on autopsy tissue from eight MS patients who died either in the course of acute MS (Marburg’s type, Marburg, 1906) or in the course of a fulminant exacerbation in relapsing MS (Table 1). In the selected cases the vast majority of lesions (70–90%) were in the stage of active demyelination. The second selection criterion was that from these cases large hemispheric or double-hemispheric tissue blocks were available, which not only contained the demyelinating plaques, but also large areas of the NAWM. The cases included eight brains with active lesions either exclusively resembling Pattern II (n=4) or Pattern III lesions (n=4). The demographic data on these patients are given in Table 1. Where the cause of death was known, the causes were similar between cases dying with Pattern II or Pattern III lesions.

Table 1.

Clinical data of all cases

| Case | MS Type | Gender | Age (Years) |

Dis. Dur. (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern II A | Acute MS | male | 52 | 1.5 |

| Pattern II B | Acute MS | female | 46 | 3 |

| Pattern II C | Acute MS | female | 51 | 5 |

| Pattern II D | RRMS | female | 20 | 48 |

| Pattern III A | Acute MS | male | 45 | 0.2 |

| Pattern III B | Acute MS | male | 45 | 0.6 |

| Pattern III C | Acute MS | male | 35 | 1.5 |

| Pattern III D | RRMS | female | 40 | 120 |

| Normal controls | 4 male, | 46–84 | 0 | |

| 4 female | ||||

| Stroke | 5 male, | 66–92 | 1–115 weeks | |

| 4 female |

Acute MS = acute multiple sclerosis (Marburg’s type);

RRMS = relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; Dis. Dur. = disease duration.

Hemispheric or double-hemispheric sections of these autopsy brains were stained by immunocytochemistry for CD68 and for HLA-D as markers for microglial activation, and for proteolipid protein (PLP) as a marker for myelin injury and demyelination. We then searched in the periplaque region and normal white matter for focal areas of microglial activation in the absence of demyelination. Microglial activation was selected as a marker for putative early tissue lesions because it is the most reliable indicator for tissue injury, irrespective of whether the cause is inflammatory or neurodegenerative. From each section a detailed map of the lesions was prepared. The hemispheric or double-hemispheric blocks were then dissected into small tissue blocks containing demyelinating lesions, as well as areas of microglial activation in the absence of demyelination. Serial sections from the small blocks were then subjected to detailed immunocytochemical analysis (see later).

As a control we included autopsy tissue from nine patients with white matter stroke lesions (disease duration 1 to 115 weeks) and from eight patients without neurological disease or lesions identified neuropathologically in the central nervous system (Table 1).

LPS model

LPS-mediated lesions in the rat spinal cord were induced as described in detail before (Felts et al., 2005). Under isoflurane anaesthesia, a quarter laminectomy was performed at the T12 vertebral level and a small hole made in the dura. A drawn glass micropipette (typical external tip diameter 25 μm) was then inserted into the dorsal funiculus and 0.5 μl of LPS (100 ng/μl in saline) was injected at two adjacent sites, longitudinally 1 mm apart, at depths of 0.7 and 0.4 mm (2 μl in total). The injection site was marked by placing a small amount of sterile powdered charcoal on the adjacent dura. Control animals received injections of saline alone. LPS from Salmonella abortus equi (Sigma, Poole, UK; catalogue L-1887) was used without further purification.

Under deep isoflurane anaesthesia, adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 3 per time point) were perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.15 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 8 h and 1, 3, 5, 8, 12 and 15 days after LPS injection. The saline-injected control animals were sampled at 8 h and 1, 5 and 12 days. The spinal cord was dissected free and tissue blocks from the injection site, as well as from regions 1 cm rostral and caudal to the injection site were embedded in paraffin. Paraffin sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, Luxol fast blue as a stain for myelin, and Bielschowsky silver impregnation to label axons. Adjacent serial sections were used for immunocytochemistry as described later.

Immunocytochemistry

The immunocytochemical investigations were performed on 3 to 5 μm thick paraffin sections of both human and rat material. Sections were de-waxed, treated with hydrogen peroxide/methanol to block endogenous peroxidase, and incubated for 1 h in phosphate-buffered saline containing 10% foetal calf serum (PBS/FCS). For some of the antibodies (Table 2) antigen retrieval was performed by heating the sections for one hour in EDTA (0.05 M) in TRIS buffer (0.01 M, pH 8.5) in a household food steamer device (MultiGourmet FS 20, Braun, Kronberg/Taunus, Germany). Primary antibodies, as listed in Table 2, were applied overnight in PBS/FCS. Bound primary antibodies were visualized as described in detail before (Kutzelnigg et al., 2005), using a biotin–avidin system and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-tetra-hydrochloride (DAB; Sigma) or amino ethyl carbazole (AEC, Sigma) as a peroxidase substrate. For the CD3, CD8 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I labelling, biotinylated tyramine enhancement was used as described previously (Bien et al., 2002). As controls, sections were reacted in the absence of the primary antibody or by using an irrelevant antibody of the same class of immunoglobulin.

Table 2.

List of antibodies for immunocytochemistry

| MS |

LPS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary antibody |

Target | Source | Primary antibody |

Target | Source |

| Myelin damage | |||||

| α- MAG D7E10 | Myelin associated glycoprotein |

Doberson et al. (1985) | α- MAG D7E10 | Myelin associated glycoprotein |

Doberson et al. (1985) |

| α- MOG | 8-18C5 Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein |

Linington et al. (1988) | α- MOG 8-18C5 |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein |

Linington et al. (1988) |

| α-PLP | Proteolipid protein |

Serotec, UK MCA 839G | α-PLP | Proteolipid protein | Serotec, UK MCA 839G |

| α- CNPase | Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase |

Affiniti CA 1130 | α- CNPase | Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase |

Affiniti CA 1130 |

| Adaptive immunity | |||||

| α-CD3 | T-cells | DAKO Glostrup DK A 0452 |

W3/13 | Leukosialin; T-cells & Granulocytes |

Harlan Sera-Lab Loughborough, UK |

| α-CD4 | MHC II restricted T-cells |

Neomarkers Freemont CA Ab8 |

|||

| α-CD8 | MHC I restricted T-Cells |

DAKO C8/144 | |||

| Axonal damage | |||||

| α- NF | neurofilament | Chemicon AB 1981 | α- NF | neurofilament | Chemicon AB 1981 |

| α- APP | Amyloid Precurser Protein |

Chemicon; Temecula CA MAB 348 |

α- APP | Amyloid Precurser Protein |

Chemicon Temecula CA MAB 348 |

| Microglia-/macrophage activation | |||||

| α- Hc10 | MHC-I; α-chain | Stam et al. (1990) | |||

| α- β2M | MHC-I | DAKO A 072 | α-β2M | MHC-I | Santa Cruz sc-8361 |

| α- HLA- DR | MHC-II | DAKO CR 3/43 | α-OX6 | MHC-II | Serotec MRC Ox6 |

| α- iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthetase |

Chemicon Temecula CA AB 5384 |

α-NOS II | Inducible nitric oxide synthetase |

Chemicon Temecula CA AB 1631 |

| α-CD68 | Activated macro- phages/microglia |

DAKO MO 814 | α-ED1 | Activated macrophages/ microglia |

Serotec MCA 341 |

| α-CD163 | Scavenger receptor | Novo Castra Newcastle, UK NCL-CD163 |

α-EMAP II | Endothelial-monocyte- activating peptide II |

Abcam Cambridge UK Ab 15693 |

| α-CD14 | LPS receptor | Neomarkers Clone 14C02 |

|||

| α-AIF-1 (iba-1) | Allograft inflamma- tory factor-1 |

Wako 01-1974 | α-AIF-1 (iba-1) | Allograft inflammatory factor-1 |

Wako 01-1974 |

| α-MPO | Myelo peroxidase | DAKO A 0398 | α-MPO | Myelo peroxidase | DAKO A 0398 |

| Tissue preconditioning | |||||

| α-HIF-1 α | Hypoxia inducible factor1 α |

BD biosciences Pharmingen |

|||

| α-Hsp70 | Heat shock protein70 |

Stressgen Victoria, Canada SPA-810 |

α-Hsp70 | Heat shock protein70 | Stressgen, Victoria, Canada SPA-810 |

| BBB damage | |||||

| α- fibrin | Fibrinogen | US Biological F4200-06 | α- fibrin | fibrin | US Biological F4200-06 |

| Complement activation | |||||

| PC #42 | C9neo | S. Piddlesden Univ Cardiff, UK |

|||

| Rabbit α Rat | C9 | Rabbit α Rat | C9 | S. Piddlesden | |

| MC B7 | C9neo | ||||

Labelling for complement C9neo antigen was performed with three different antibodies (Table 2) and the immunoreactivity was similar with all the three antibodies used. To control for the validity of C9neo staining sections from patients in the acute stage of neuromyelitis optica were used (Lucchinetti et al., 2002). In these sections a selective and strong staining was seen on astrocytes of the perivascular and subpial glia limitans, expanding in a rim or rosette pattern into the lesion, in the absence of reactivity on myelin sheaths or myelin degradation products within macrophages.

Death of oligodendrocytes, resembling apoptosis, was identified by morphological criteria (nuclear condensation and/or fragmentation) as well as by staining for DNA fragmentation as described before (Aboul Enein et al., 2003).

Confocal laser fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections as described earlier with few modifications. For confocal fluorescent double labelling with polyclonal anti-fibrin and monoclonal anti-AIF-1, anti-GFAP, anti-PLP or anti-NF, primary anti-bodies were applied simultaneously at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies consisting of goat-anti-mouse Cy2 or goat-anti-mouse Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:200) and biotinylated anti-rabbit (Amersham; 1:200) were applied simultaneously for 1 h at room temperature. The labelling was finished by application of streptavidin-Cy2 or streptavidin-Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch; 1:75) for 1 h at room temperature. Fluorescent preparations were examined using a confocal laser scan microscope (LSM 410, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Quantitative evaluation

MS tissue

A section of each MS tissue block (hemispheric sections as well as small sections) was scanned and a detailed map of the lesions was prepared, in which morphologically distinct regions within the white matter as defined later in the ‘Results’ section (normal white matter; putative ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions, and actively demyelinating lesions) were manually outlined. When multiple serial sections were used for immunocytochemical examination, the maps of the first and last sections were compared to confirm that the area of the lesion included in the quantitative analysis remained valid. Areas to be analysed by cell counting were categorized according to the areas marked on the maps. Counting was performed manually using a calibrated ocular graticule. For each lesion area the immunostained cells were counted in six microscopic fields (total area 1.6 mm2), and the counts expressed as cells/mm2 of tissue area.

LPS model

Since the lesions in the LPS model were restricted to the central portion of the dorsal funiculus at the site of injection, quantitative analysis was restricted to this area. As with the MS tissue, cell counts were performed in serial sections stained immunocytochemically for the different markers. The first and last section of the series was again used to outline the area of the lesion within the respective maps. Cell counting was performed manually at the microscopic level as described earlier for MS sections.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were analysed by statistical evaluation using non-parametric tests. Descriptive analysis included mean values and SE. Differences between two groups were assessed with Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U-test. Significant values were corrected with Shaffer’s procedure for multiple testing. SPSS 14.0 statistical software system (SPSS Inc., Chicago) was used for calculations. A P-value ≤0.05 is considered statistically significant. The non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation was used to identify interdependence of variables.

Results

We first searched for focal areas of microglial activation in the absence of demyelination in the NAWM of controls and MS patients using large hemispheric or double-hemispheric sections, labelled immunocytochemically for CD68 and HLA-D. In sections from control brain we found scattered CD68 or HLA-D expressing microglial cells, diffusely dispersed within the brain white matter. No focal areas of microglial activation or microglial nodules were found. Sections from MS brains showed multiple inflammatory demyelinating lesions in the white matter. Due to the nature of the disease [acute MS or relapsing remitting MS (RRMS) with fulminant exacerbations] the majority of the lesions were in the stage of active demyelination. Focal areas of microglia activation outside of demyelinating plaques were seen in patients following Pattern III, but not in those with Pattern II demyelination.

Pattern II plaques in MS patients are formed by confluence of perivenous demyelinating lesions:

In MS patients exhibiting lesions of the Pattern II type of demyelination, numerous actively demyelinating lesions were present that were characterized by lymphocytic and intense macrophage infiltration (Suppl Fig. 1a–c). Macrophages contained abundant myelin degradation products, reactive for all the myelin antigens examined. At the edges of such lesions a dense rim of macrophages was present (Suppl Fig. 1b), located between demyelinated axons as well as other axons with partly destroyed myelin sheaths. As described before (Lucchinetti et al., 2000) precipitation of activated complement (C9neo) was detected in these regions. Numerous axonal spheroids were found in the lesions, indicating acute axonal injury and transection. Activated ramified microglial cells containing myelin degradation products were present at the edge of the lesions and were often associated with partly damaged myelin sheaths.

In the NAWM (i.e. white matter that appears normal upon gross examination) numerous small veins were found with perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, which spread into the adjacent parenchyma of the white matter (Suppl Fig. 1). This inflammatory infiltration was regularly associated with active myelin destruction and axonal injury. At the edge of demyelinating plaques the density of veins with perivascular inflammation and demyelination was higher than in the NAWM distant from lesions (Suppl Fig. 1a–k). Confluence of perivenous demyelinating lesions associated with the active plaques was frequently seen at the plaque margins. No preferential loss of MAG was seen in perivascular lesions (Suppl Fig. 1f and g). Perivascular infiltrates contained numerous T-cells (mainly CD8+), which dispersed into the adjacent perivascular area of demyelination. Demyelination was associated with profound macrophage activation (Fig. 1h) and perivascular deposition of C9neo antigen (Suppl Fig. 1j). Focal areas of microglial activation in the NAWM, distant from plaques, were not observed.

MS tissue with Pattern III demyelination reveals focal plaques of microglial activation in the NAWM in the absence of demyelination:

As described before, active Pattern III lesions show the histological features of tissue injury closely resembling hypoxia-like damage. In these lesions perivascular inflammation is present, but these perivascular inflammatory infiltrates are frequently surrounded by a rim of intact tissue (Aboul Enein et al., 2003). Thus demyelination within these white matter lesions occurs at a short distance from the vessel, rather than immediately adjacent to it, as occurs with Pattern II demyelination, for example. Actively demyelinating Pattern III lesions showed primary demyelination (Fig. 1a–e), a variable extent of axonal injury (Fig. 1f and g), preferential loss of MAG (Fig. 1d and e) and CNPase, and apoptosis-like cell death of oligodendrocytes, but no complement C9neo deposition (Aboul Enein et al., 2003). Active demyelination is associated with a diffuse infiltration of the tissue by T-lymphocytes, in which CD8+ T-cells massively outnumber CD4+ cells (Table 3). Infiltration of the tissue by B-cells is low in comparison with T-cells, and variable between different lesions. Macrophages and activated microglia strongly express a range of activation markers, including MHC Class I and Class II antigens, CD 68, CD163, allograft-inflammatory factor-1 (AIF-1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and myeloperoxidase (MPO; Fig. 2, Table 3).

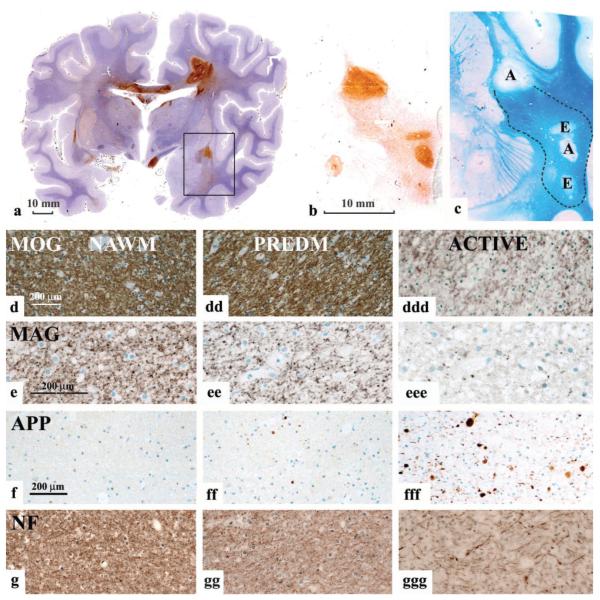

Fig. 1.

Pattern III lesions. (a) Hemispheric brain section, labelled immunocytochemically for CD 68 (Case Pattern III C). There are multiple actively demyelinating lesions that show very dense immunoreactivity for CD68. In addition there are broad areas around the plaques, as well as areas independent from plaques that show weak reactivity for CD68 (areas of microglial activation). The rectangle indicates the area of the brain, shown in Fig. b and c. (b and c) Higher magnification of the area shown in the rectangle in (a). Serial sections are labelled immunocytochemically for CD 68 (b), and stained with Luxol fast blue (c). Areas with strong CD68 reactivity indicate areas of active demyelination (labelled with A in Fig. 1c). Areas with moderate CD68 expression show oedema in LFB-stained sections in the absence of active demyelination (E in Fig.1c). In addition there is a broad area of diffuse microglial activation (Fig.1b) between the active plaques, which shows a variable reduction in myelin density (lower part of the figures); this area is outlined in dashed lines in Fig. 1c. (d–g) Immunocytochemistry for myelin antigens (indicated), for APP and neurofilament (NF) in the normal appearing white matter (NAWM; d, e, f, g). Areas of diffuse microglial activation (‘pre demyelinating’: PREDM; dd, ee, ff, gg) and areas of actively demyelinating lesion (ddd, eee, fff, ggg) are shown. In comparison with the NAWM,‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions show similar MOG immunoreactivity, no demyelination and no macrophages with myelin degradation products, but some vacuoles, suggesting oedema. Immunoreactivity for MAG is profoundly reduced in ‘pre-demyelinating area’ in comparison to NAWM, and the labelling is in part fragmented into small granular structures. Some axons with immunoreactivity for amyloid precursor protein are seen in the ‘pre-demyelinating’ area, suggesting acute axonal injury, but there is no visible axonal loss in sections stained for neurofilament. In classical, active lesions there is a massive reduction in immunoreactivity for MOG, but there are still MOG-reactive fibres present. There are also many macrophages with MOG-reactive degradation products. In contrast, MAG reactivity is completely lost; numerous axons contain immunoreactivity for APP and the axonal density is clearly reduced in sections stained for neurofilament.

Table 3.

Expression of different antigens in pattern III MS lesions and control brain (cells/mm2)

| Marker | Control WM | ‘PreDM’ Pattern III | Active Pattern III |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 | 7.6 ± 2.9 | 51.7 ± 12.5* | 123.7 ± 30.9*,# |

| CD4 | n.d. | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 19.7 ± 7.5 |

| CD8 | n.d. | 46.4 ± 12.5 | 106.0 ± 32.3 |

| CD68 | 80 ± 7.5 | 213.0 ± 10.6* | 426.1 ± 53.8*,# |

| HLA-DR | 55.6 ± 3.5 | 245.8 ± 20.9* | 526.4 ± 58.7*,# |

| MHC I alpha | 65.2 ± 14.4 | 70.9 ± 16.2 | 142.4 ± 41.8* |

| Beta 2 Microgl. | 48.8 ± 8.7 | 62.6 ± 13.1 | 130.1 ± 92.4* |

| INOS | 4.8 ± 2.5 | 86.5 ± 14.0* | 141.3 ± 36.6* |

| MPO | 1.7 ± 1 | 70.2 ± 33.0* | 88.3 ± 56* |

| HIF-1α | 0.0 | 7.3 ± 2.5* | 0.0# |

| Fibrin | 0.0 | Precipitates | Diffuse |

| Hsp 70 | 0.0 | 79.5 ± 18.4* | 42.2 ± 10.3* |

| Ax. Injury (APP) | 4.0 ± 3.1 | 50.1 ± 10.4* | 157.3 ± 54.5* |

| Demyelination | − | − | +++ |

n.d. = not done.

Significantly different from controls.

Significantly different between ‘pre-demyelinating’ and active.

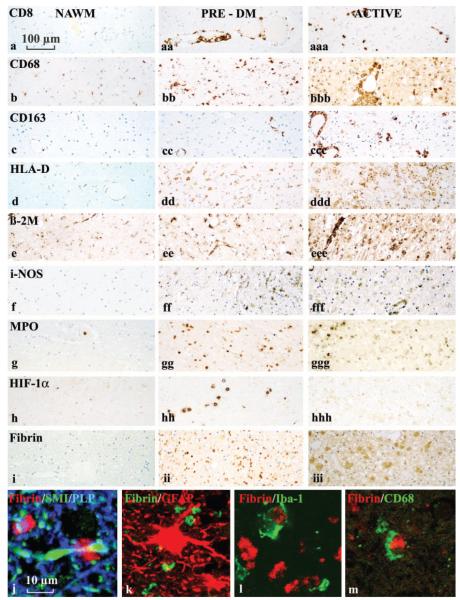

Fig. 2.

Inflammation and microglial activation in different stages of Pattern III lesions in comparison with that in the NAWM. This figure is organized into three columns, showing tissue from the NAWM,‘pre-demyelinating’ and actively demyelinating lesions respectively, in MS patients exhibiting Pattern III demyelination. The rows show the expression of CD8+ (MHC I-restricted T-cells (a), different macrophage and microglial activation markers (b–g), HIF-1α (h) and fibrin (i–m). T-cells in ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions are restricted to the perivascular space (aa), while they diffusely disperse into the lesion in active plaques (aaa).‘Pre-demyelinating’ lesions show profound upregulation in microglia of CD68, HLA-D, iNOS and MPO, while in active lesions the most extensive expression is seen for CD68 and MHC Class I (β2M). HIF-1α is mainly expressed in ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions. Immunocytochemistry for fibrin shows fibrin precipitates in ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions, while in active lesions the immunoreactivity is diffuse, and also, in part, present within the cytoplasm of activated astrocytes. (j–m) Confocal double labelling for fibrin and other cellular markers (neurofilament and PLP in j; GFAP in k; AIF-1/Iba-1 in l and CD68 in m). Because there is no co-labelling, we conclude that the fibrin precipitates are present in the extracellular space, although they are closely attached to axonal spheroids (j) and to activated microglial cells (l and m).

In the NAWM of Pattern III cases we did not find perivenous demyelinating lesions similar to those seen in Pattern II cases. However, we did find abundant areas of microglial activation in the absence of detectable demyelination, in regions devoid of myelin degradation products within macrophages or microglia. Such areas of microglial activation were found in a broad zone surrounding the border of actively demyelinating lesions, but were less frequently also present as separate lesions, which occurred independently from actively demyelinating plaques (Fig. 1a–c). To confirm the independence of such lesions from demyelinating plaques we also performed serial sections through the entire lesion. These findings suggest that focal areas of microglial activation may precede the formation of demyelinating plaques in MS patients exhibiting hypoxia-like, Pattern III demyelination. These changes were found in all Pattern III cases, but most profound in patients IIIA and IIIC.

Immunopathology of ‘pre-demyelinating’ Pattern III lesions

In sections stained for myelin by Luxol fast blue, areas of microglial activation appeared as regions with some vacuolated tissue texture and reduced myelin density, apparently reflecting widening of extracellular space by oedema. Immunocytochemistry for different myelin antigens [MAG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), PLP and CNPase] confirmed the reduced density of myelinated fibres and revealed a further reduction in the staining for MAG and CNPase in comparison with that in the adjacent normal white matter (Fig. 1d to eee). However, oligodendrocyte apoptosis or active demyelination indicated by the presence of myelin degradation products in macrophages or microglia, were absent. Furthermore, abnormally thin myelin sheaths, suggesting remyelination were not present in these areas. Despite being surrounded by intact myelin, some axons within these lesions accumulated amyloid precursor protein (APP), suggesting a low degree of axonal injury (Fig. 1f to fff), but there was no detectable loss of axons in sections stained for neurofilament (Fig. 1g to ggg). From these data we conclude that during an initial stage of their formation, Pattern III lesions consist of mild oedema, microglial activation and changes of the distal oligodendrocyte processes (i.e. the inner layers of the myelin sheath) in the absence of overt myelin destruction.

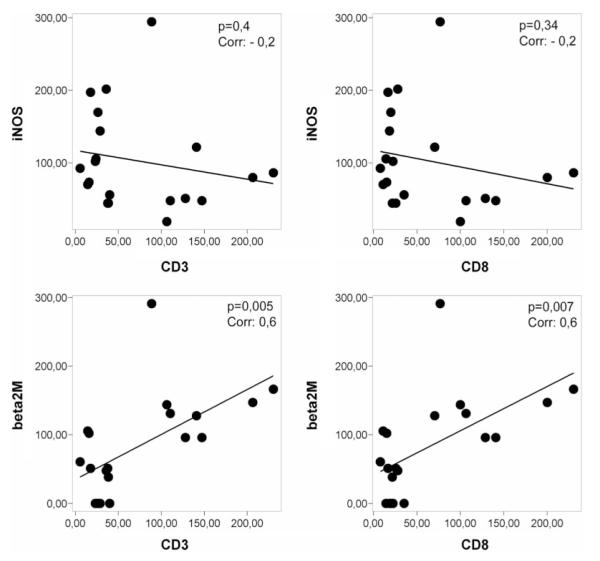

Inflammatory infiltrates, mainly consisting of CD8+ T-lymphocytes, were invariably present within such areas of microglial activation. However, in contrast to actively demyelinating lesions, such lymphocytic infiltrates were sparse and restricted to the perivascular space (Fig. 2a). In addition, the activation patterns of microglia were different from those seen in actively demyelinating lesions (Fig. 2). We found a prominent expression of i-NOS, MPO and HLA-D, while up-regulation of MHC-Class I antigen (alpha chain as well as ß2 microglobulin), CD 163, AIF-1 and CD14 was moderate or low (Fig. 2, Table 3). Furthermore, when active lesions and ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions were pooled we found a significant positive correlation between T-cell infiltration and MHC-Class I expression, but no correlation between T-cell infiltration and either iNOS or MPO expression (Fig. 3). Polymorphonuclear leukocytes were absent in these lesions.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between T-cell infiltration in lesion areas and expression of microglia activation antigens. There is a significant correlation between the number of CD3+ T-cells and the expression of MHC-class I in microglia within lesions. This is not the case for iNOS expression.

Another characteristic feature, seen in ‘pre-demyelinating’ areas of microglial activation was the presence of precipitates of fibrin within the extracellular space of the lesions (Fig. 2i–m). Examination by confocal microscopy, utilizing double labelling techniques, revealed that such fibrin deposits were mainly found attached to activated microglia, and to axons at the nodes of Ranvier. In contrast, in actively demyelinating Pattern III lesions, such fibrin deposits were no longer present, but rather the fibrin immunoreactivity was diffusely dispersed throughout the tissue, and in part also located within the cytoplasm of astrocytes and axons.

Proteins, involved in tissue preconditioning are up-regulated in ‘pre-demyelinating’ but not in actively demyelinating lesion areas:

We have recently shown that proteins involved in tissue preconditioning, such as hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), are highly expressed at the borders of active Pattern III lesions as well as in the bands of preserved myelin in MS lesions showing concentric demyelination (Aboul Enein et al., 2003; Stadelmann et al., 2005). From these results we suggested that tissue preconditioning may protect white matter tissue from lesion expansion in active Pattern III lesions. We have thus analysed the expression of HIF-1α and Hsp70 in the focal areas of microglial activation in the NAWM of patients exhibiting Pattern III demyelination. We found immunoreactivity for both proteins in such ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions (Fig. 2h; Table 3). HIF-1α immunoreactivity was present in nuclei of cells, morphologically resembling oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, while Hsp70 was expressed in the cytoplasm of all different glial cell types (Stadelmann et al., 2005). In contrast, the expression of these molecules was lower or absent in lesions showing active demyelination.

The development of Pattern III MS lesions is reproduced in the experimental model of LPS-induced demyelination:

We recently described that demyelinating lesions closely similar to Pattern III lesions in MS patients can be experimentally induced by focal injection of LPS into the white matter of the rat spinal cord (Felts et al., 2005). An interesting feature of this model is that demyelination ensues only after a time lag of 5 to 8 days after LPS injection (Fig. 4a). Demyelination starts by profound alterations in the periaxonal oligodendrocyte loops, which are associated with selective loss of MAG, while PLP is still preserved (Felts et al., 2005). Similar to the Pattern III lesion, demyelination occurred in conjunction with macrophage and microglial activation, and the prominent expression of iNOS. We therefore used this model to study in detail the initial tissue changes which precede demyelination, and to compare them with the changes described earlier for Pattern III MS lesions.

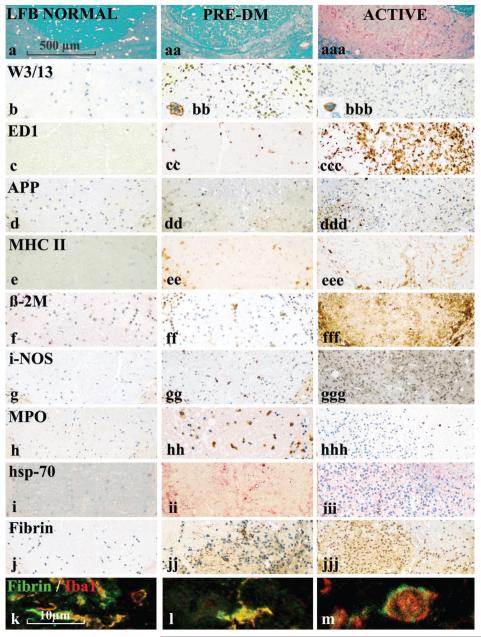

Fig. 4.

Inflammation and microglial activation in the LPS-induced demyelinating lesion during the pre-demyelinating phase and the phase of active demyelination. The figure is organized into three columns, showing respectively normal control tissue, and lesioned tissue during the pre-demyelinating period (1 to 5 days post-LPS injection) and the actively demyelinating period (12 days post-LPS injection). In comparison with normal spinal cord there is some reduction of myelin density (LFB staining) in the pre-demyelinating stage, primarily due to oedema, and profound loss of myelin staining in the active lesions (row a). W3/13, a marker for granulocytes and T-cells, shows profound granulocyte and T-cell infiltration of the tissue in the early pre-demyelinating stage (8 h and 1day after LPS injection), with moderateT-cell infiltration in active lesions (see also inserts). APP staining shows some axonal injury in the ‘pre-demyelinating’ stage and massive axonal damage when lesions actively demyelinate. The expression patterns of microglia/macrophage activation antigens is essentially similar to that seen in Pattern III MS lesions (Fig. 3), although the expression of these molecules is mainly found in cells with a macrophage phenotype (round cells) rather than a microglial appearance. Hsp 70 (visualized in red colour) as a marker for tissue preconditioning is mainly expressed during the pre-demyelinating stage. Immunocytochemistry for fibrin shows fibrin precipitates (dark-brown structures) in the pre-demyelinating stages, but diffuse reactivity in the active lesions. (k–m) Confocal double labelling of fibrin precipitates in the pre-demyelinating stage with the microglia/macrophage marker AIF-1/iba-1 shows precipitation of fibrin on the surface of microglial cells and macrophages.

As described previously (Felts et al., 2005), we found in the early stages (8 h to 1 day after LPS injection) infiltration of the tissue by polymorphonuclear granulocytes, which was followed by a mild T-cell infiltration (Fig. 4b, Table 4), together with some macrophage infiltration and profound microglial activation (Fig. 4c, Table 4). iNOS expression showed a bimodal pattern, with strong expression in individual microglia peaking on day 1 and weak expression peaking on day 12. MPO expression in macrophages and microglia reached a peak at day 3, and declined thereafter (Fig. 4g and h, Table 4). MPO was also seen in granulocytes within the first days after LPS injection. In addition we found massive precipitation of fibrin during the early stages of this model (days 1–8; Fig. 4j–m). Double labelling of fibrin and other cellular markers revealed that fibrin deposits predominantly dressed the surface of activated microglia and macrophages. At this stage of lesion development there was almost no demyelination evident, although a few macrophages contained myelin reactive degradation products. Nonetheless, there was a significant increase in the number of axons showing immunoreactivity for APP, in comparison with controls (Fig. 4d, Table 4). As in ‘pre-demyelinating’ MS lesions, we found a profound focal expression of Hsp70 at the injection site during the first 3 days after LPS injection (Fig. 4i; Table 4).

Table 4.

Expression of different antigens in LPS lesions and normal white matter (cells/mm2)

| Marker | NWM | 0.3d | 1d | 3d | 5d | 8d | 12d | 15d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W3/13 | 0.5±0.2 | 190±36 | 170±17 | 32±9 | 14±2 | 14±4 | 41±9 | 23±1 |

| ED1 | 4±3 | 38±6 | 171±39 | 165±18 | 117±67 | 133±7 | 379±49 | 453±43 |

| EMAP | 28±6 | 18±4 | 176±17 | 250±18 | 207±83 | 388±7 | 478±48 | 530±56 |

| MHC II (Ox6) | 5±2 | 13±3 | 42±2 | 72±14 | 47±14 | 101±7 | 80±19 | 72±7 |

| MHC I ß2M | 2±2 | 24±6 | 67±18 | 122±25 | 77±7 | 359±63 | 407±34 | 479±33 |

| iNOS | 0 | 13±2 | 13±6 | 0 | 0 | 14±1 | 41±9 | 23±2 |

| MPO | 0 | 16±4 | 45±8 | 85±38 | 43±6 | 34±9 | 11±2 | 4±0.3 |

| Hsp 70 | 22±2 | 129±19 | 174±17 | 126±44 | 33±14 | 36±4 | 22±2 | 24±1 |

| Fibrin | 0 | P + | P ++ | P ++ | P ++ | P +++ | D ++ | D + |

| APP | 1±1 | 3±1 | 8±5 | 24±6 | 13±5 | 316±38 | 265±53 | 131±20 |

| DEMY | 0 | 0 | 0 | +/− | + | + | ++ | ++ |

P = fibrin precipitates; D = diffuse fibrin reactivity.

Demyelination in this model started between day 5 and 8 after LPS injection (Fig. 4a), and was associated with massive acute axonal injury, the latter evidenced by the intra axonal accumulation of APP (Fig. 4d, Table 4). These events were associated with substantial infiltration of the lesions by macrophages. Early myelin degradation products in macrophages, detected by their immunoreactivity for MOG or PLP, peaked at day 12 and at later stages were replaced by empty vacuoles, reflecting the later neutral lipid phase of myelin degradation. At this stage of lesion development the expression of MPO in macrophages and microglia was low, as was the expression of Hsp70 in glial cells. Fibrin deposits were still present until day 8, but were absent in established demyelinated lesions at days 13 and 15. In these lesions only diffuse fibrin reactivity was found (Fig. 4j, Table 4).

Immunopathology of stroke lesions

Areas of microglial activation in the vicinity of active Pattern III lesions could reflect Wallerian degeneration, due to axonal transsection in active plaques. We therefore analysed perilesional tissue of brain infarcts. In these areas profound axonal loss and axonal spheroids were present. There was a moderate microglial activation, reflected by the expression of CD68, but expression of i-NOS and MPO or the precipitation of fibrin was absent. Although described before in thick myelinated fibres in the spinal cord (Buss and Schwab, 2003), we did not detect preferential loss of MAG or CNPase in areas of Wallerian degeneration around stroke lesions in the brain. Profound microglial activation was seen within the infarct lesions. The pathological hallmarks of different types of MS lesions, and in stroke lesions are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of pathological alterations in MS pattern II and pattern III lesions in comparison to areas of wallerian degeneration (stroke) and normal white matter of controls

| MS Pattern II Perivenous |

Active | MS Pattern III Pre-DM |

Active | WD | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-cells | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | +/− | +/− |

| CD68 | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | +/− |

| MHC I | +++ | +++ | +/− | +++ | +/− | +/− |

| i-NOS | + (MO) | + (MO) | ++ (MG) | ++ (MO) | − | − |

| MPO | + | + (MO) | ++ (MG) | ++ (MO) | − | − |

| MAG Loss | − | − | + | +++ | − | − |

| APP | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | − |

| HIF 1a | − | − | + | +/− | − | − |

| Dysferlin | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | +/− | − |

| Fibrin | D | D | P | D | +/−D | − |

| C9neo | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − |

WD = Wallerian Degeneration around stroke lesions; Pre-DM = ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions; MHC I=Class I MHC antigen;

i-NOS = inducible nitric oxide synthase; MPO = myeloperoxidase; MAG-loss = preferential loss of myelin associated glycoprotein;

APP = axonal expression of amyloid precursor protein (axonal injury); HIF-1a = hypoxia inducible factor 1a; Dysferlin = endothelial expression of dysferlin as a marker for leaky endothelial cells; Fibrin: P = precipitates; D = diffuse reactivity; C9neo = Complement C9neo antigen;

MO = macrophages; MG = microglia.

Discussion

This study has focussed on the early (initial) stages of lesion development that largely precede the formation of the classical inflammatory demyelinating plaques of MS. The study has selected for close examination cases with fulminant disease, showing abundant actively demyelinating lesions in the central nervous system, and in whom large hemispheric sections were available, which allow a detailed analysis of perilesional and distant NAWM. Changes in the NAWM, suggestive of pre-demyelinating lesions, were found only in those patients, exhibiting Pattern III, and thus not in patients with Pattern II demyelination (Table 5). We have compared the findings in MS with those from the study of the model of inflammatory demyelinating lesion resulting from the intraspinal injection of LPS into the rat dorsal columns (Felts et al., 2005). The development of the tissue injury in both the human and rat lesions was found to be closely similar, suggesting that the mechanisms involved in their formation may be comparable. This fact, combined with the morphological features of the lesions, suggest that mechanisms associated with innate immunity may play a role in the formation of both types of lesion.

The clinical part of this study is based on a sample of highly selected MS cases. The patients presented with a rapidly progressive inflammatory disease with disseminated lesions throughout the entire central nervous system. Their pathology was fully consistent with that, described in the seminal study by Marburg (1906) for acute MS. We selected these cases on the basis of the fulminant activity of their lesions, since in such cases the chance for detecting very early or even ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions is high. Our study does not answer the question, whether similar ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions also occur in more classical cases with a milder disease course and in particular in patients with active lesions, following Pattern I of demyelination according to Lucchinetti et al. (2000).

However, previous MRI studies have shown that focal changes in the NAWM in classical MS can be found at locations that later develop into focal T2 lesions that enhance with gadolinium. These alterations consisted of subtle differences in MTR signals and some reduction in the signal for N-acetyl aspartate using MRS (Filippi et al., 1998; Narayanan et al., 1998). These changes precede Gd-enhancement in active lesions, implying that the blood–brain barrier is intact at the earliest stages of lesion development. In contrast, we observed in ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions some oedema and fibrin extravasation. The explanation may reside in the fact that Gd-enhancement is a very insensitive marker for detection of blood–brain barrier dysfunction and its absence does not rule out subtle changes in blood–brain barrier permeability (Silver et al., 2001), such as those we observed histologically. Thus, overall, the MRI alterations preceding lesion formation are consistent with the pathological alterations described here in ‘pre-demyelinating’ Pattern III lesions. Considering, however, the low number of such MRI defined pre-demyelinating lesions within classical MS patients it may be difficult to identify them in pathological studies without knowledge of their exact location from pre-mortem MRI studies. It thus remains unresolved, whether such lesions are similar compared to those described here in fulminant Pattern III cases.

The patterns of microglial activation in “pre-demyelinating” Pattern III MS lesions, and in the pre-demyelinating stage of LPS-induced lesions, was different from that seen in actively demyelinating lesions. In the pre-demyelinating stage the microglia showed high immunoreactivity for iNOS and MPO, while MHC Class I antigens, CD163 (a scavenger receptor; Weaver et al., 2007) and AIF-1 (a marker for macrophage/microglia activation; Deininger et al., 2002) were expressed only at low levels. In contrast, in actively demyelinating lesions the latter molecules were prominently expressed, but the expression of iNOS and MPO either stayed stable, or decreased. These observations suggest that microglia in the pre-demyelinating stages are mainly activated for the production of oxygen and nitrogen radicals: when demyelination starts a different programme of activation for macrophages and microglia is turned on. These data are consistent with our previous hypothesis that mitochondrial injury, induced by oxygen and nitrogen radicals, plays a role in the initiation of hypoxia-like tissue injury in Pattern III lesions. Whether the ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions described here are similar to those described as (p)reactive lesions in progressive MS (De Groot et al., 2001) remains unclear. It has, however to be considered that ‘(p)reactive’ lesions in the study of De Groot et al. (2001) accounted for 27% of all lesions found in the respective patients. This seems to be a very high percentage for ‘pre-demyelinating’ lesions within the brain of patients with progressive MS. No effort was done in the study by De Groot et al. (2001) to differentiate them from remyelinated shadow plaques, which can frequently be encountered in patients with progressive MS (Patrikios et al., 2006).

It is not yet clear what drives microglial activation in ‘pre-demyelinating’ Pattern III lesions. Cytokines, produced by T-lymphocytes, are one possibility. Although there is good agreement between different pathological studies that T-cell infiltration is only mild at the very early stages of focal white matter lesions (it becomes massively increased at the time when active demyelination starts; Gay et al., 1997; Barnett and Prineas, 2004), this observation does not rule out a possible role for T-cells. Thus although, as described before by Barnett and Prineas (2004), T-cells were largely absent from the lesion parenchyma in the earliest stage of lesion formation, these cells were present in small perivenous inflammatory infiltrates within or adjacent to the lesions. Therefore T-cell-mediated disturbance of the blood–brain barrier or liberation of pro-inflammatory cytokines might contribute to the microglial activation. However, an argument against an essential role for T cells is our finding that lesions essentially similar to Pattern III lesions can be induced by the intraspinal injection of LPS, which occurs in the absence of a T-cell- or B-cell-mediated adaptive immune response (Felts et al., 2005). It seems reasonable to propose that activation of microglia through the mechanisms of innate immunity alone is sufficient to induce Pattern III-like lesions.

If an innate immune response is involved, the question arises how this might be triggered in microglia in MS tissue. In the LPS model direct stimulation of microglia via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR-2 & −4) is one mechanism (Jung et al., 2005). However, despite the use of LPS in the experimental lesion it should not necessarily be concluded that bacteria are involved in the initiation of Pattern III lesions. Indeed, our study has identified another possible factor, namely fibrin, which can activate microglia via TLR-4 (Smiley et al., 2001) and CD11b integrin receptor signalling (Altieri et al., 1988; Flick et al., 2004). Furthermore, fibrin precipitation within the nervous system is neurotoxic, possibly due to microglial activation (Akassoglou et al., 2004; Adams et al., 2007). In addition, it is possible that impaired fibrinolysis in MS lesions may contribute to fibrin precipitation (Gveric et al., 2003). The profound precipitation of fibrin on the surface of microglia, observed in the present study, may thus be a major force driving microglial activation in ‘pre-demyelinating’ Pattern III lesions, and it may also amplify microglial activation in the LPS model.

MRI studies have revealed that lesions in MS can start their genesis several days or weeks before the appearance of the classical inflammatory demyelinating plaque (Filippi et al., 1998; Narayanan et al., 1998; Wuerfel et al., 2004). Our findings suggest that the relatively slow progress of such lesions may be due, in part, to the onset of protective mechanisms in which the tissue becomes pre-conditioned to withstand future insults, such as those from hypoxia-like conditions. Sublethal tissue injury, particularly sublethal hypoxia, is known to result in the up-regulation of HIF-1α and its downstream regulated gene products, as well as the induction of stress proteins (Bergeron et al., 2000; Bernaudin et al., 2002; Christians et al., 2002). When such proteins are expressed, cells become partly protected against further damage (Sharp et al., 2001; Sharp and Bernaudin, 2004). Interestingly, we found HIF-1α and Hsp70 expression in ‘pre-demyelinating’ Pattern III MS lesions, and also in the pre-demyelinating stage in the LPS model, but this expression was low or absent when active demyelination started. Thus tissue preconditioning may not only be involved in the formation of concentric preserved rims of myelin in Balo’s type of MS (Stadelmann et al., 2005), but may, in more general terms, counteract the progression of ‘pre-demyelinating’ Pattern III lesions into demyelinated plaques. However, liberation of heat shock proteins from dying cells can further activate microglia or macrophages by signalling through TLRs and may under these circumstances augment tissue injury (El Mezayen et al., 2007).

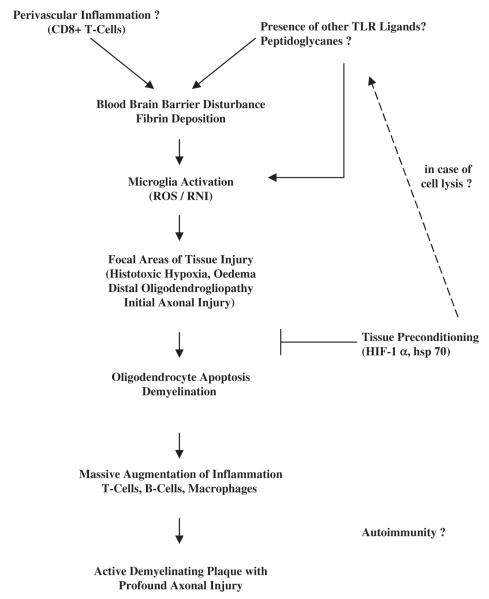

In conclusion, the current findings have revealed early changes in the NAWM that can precede the formation of inflammatory demyelinating plaques in some patients, namely those exhibiting the hypoxia-like changes of Pattern III demyelination. Such changes may be the tissue correlate of the subtle alterations in signal detected prior to the appearance of classical lesions by MRI. The finding that a closely similar sequence of tissue changes occurs in the model of LPS-induced demyelination suggests that this model may provide an opportunity to study in detail the sequence of tissue changes involved in the genesis of Pattern III MS lesions. Knowledge of this sequence may provide opportunities for therapeutic intervention. From our data we postulate that the following sequence of events may be involved in the formation of focal demyelinating Pattern III lesions (Fig. 5). First, there is a focal activation of microglia (see later) that produce a host of agents (notably reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, including nitric oxide) which cause mitochondrial impairment and hypoxia-like injury of the local axons and supporting cells. The growth of such focal tissue injury may be limited by the expression of molecules involved in tissue preconditioning. When the balance between destructive and protective mechanisms shifts towards further tissue injury, oligodendrocyte apoptosis and demyelination may ensue. These changes can be associated with a massive augmentation of the inflammatory response, and a profound infiltration of the tissue by T-cells, B-cells and macrophages which finally lead to the formation of the classical inflammatory demyelinating plaque. What drives the initial microglial activation is not yet clear, but the current findings focus attention on the possibility that fibrin precipitates on the microglial surface may be an important factor. Fibrin could enter the CNS through a blood–brain barrier which is moderately damaged by the perivascular T-cell infiltrates. Whether additional endogenous or exogenous TLR ligands are present in the MS lesions is not clear, although in some lesions bacterial peptidoglycans have been observed (Schrijver et al., 2001; Visser et al., 2005).

Fig. 5.

Hypopthetical pathway of lesion formation in pattern III MS cases. TLR = toll-like receptors; ROS = reactive oxygen species; RNI = reactive nitrogen intermediates; HIF = hypoxia-inducible factor; hsp = heat shock protein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the European Union (Project ‘NeuroproMiSe’ LSHM-CT-2005-018637, by the FWF, Austria, Project P19854-B02, the Medical Research Council (UK) and the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. We thank Ulrike Köck, Angela Kury and Marianne Leiszer for expert technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MTR

magnetization transfer ratio

- NAWM

normal-appearing white matter

Footnotes

Supplementary material Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

References

- Aboul-Enein F, Rauschka H, Kornel B, Stadelmann C, Stefferl A, Brück W, et al. Preferential loss of myelin associated glycoprotein reflects hypoxialike white matter damage in stroke and inflammatory brain diseases. J Neuropath Exp Neurol. 2003;62:25–33. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RA, Bauer J, Flick MJ, Sikorski S, Nuriel T, Lassmann H, et al. The fibrin-derived γ377–395 peptide inhibits microglia activation and suppresses relapsing paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204:571–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akassoglou K, Adams RA, Bauer J, Mercado P, Tseveleki V, Lassmann H, et al. Fibrin depletion decreases inflammation and delays the onset of demyelination in a tumor necrosis factor transgenic mouse model for multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303859101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri DC, Bader R, Mannucci PM, Edgington TS. Oligospecificity of the cellular adhesion receptor Mac-1 encompasses an inducible recognition specificity for fibrinogen. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1893–900. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babinski J. Recherches sur l’anatomie pathologique de la sclerose en plaque et etude comparative des diverses varietes de la scleroses de la moelle. Arch Physiol (Paris) 1885;5–6:186–207. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MH, Prineas JW. Relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis: pathology of the newly forming lesion. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:458–68. doi: 10.1002/ana.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron M, Gidday JM, Yu AY, et al. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in hypoxia-induced ischemic tolerance in neonatal rat brain. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:285–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaudin M, Tang Y, Reilly M, et al. Brain genomic response following hypoxia and re-oxygenation in the neonatal rat. Identification of genes that might contribute to hypoxia-induced ischemic tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39728–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien CG, Bauer J, Deckwerth TL, Wiendl H, Deckert M, Wiestler OD, et al. Destruction of neurons by cytotoxic T cells: a new pathogenic mechanism in Rasmussen’s encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:311–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsch A, Wegener C, da Costa C, Bunkowski S, Reimers CD, Prange HW, et al. Lesion development in Marburg’s type of acute multiple sclerosis: from inflammation to demyelination. Mult Scler. 1999;5:138–46. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booss J, Esiri MM, Tourtellotte WW, Mason DY. Immunohistological analysis of T lymphocyte subsets in the central nervous system in chronic progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1983;62:219–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(83)90201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Schwab ME. Sequential loss of myelin proteins during Wallerian degeneration in the rat spinal cord. Glia. 2003;42:424–32. doi: 10.1002/glia.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christians ES, Yan LJ, Benjamin IJ. Heat shock factor-1 and heat shock proteins: critical partners in protection against acute cell injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JW. The histology of disseminated sclerosis. Trans R Soc. 1916;50:517–40. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot CJA, Bergers E, Kamphorst W, Ravid R, Polman F, Barkhof F, et al. Post-mortem MRI-guided sampling of multiple sclerosis brain lesions. Increased yield of active demyelinating and (p)reactive lesions. Brain. 2001;124:1635–45. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.8.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger MH, Meyermann R, Schlüsener HJ. The allograft inflammatory factor-1 family of proteins. FEBS Lett. 2002;514:115–21. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobersen MJ, Hammer JA, Noronha AB, et al. Generation and characterization of mouse monoclonal antibodies to myelin associated glycoprotein (MAG) Neurochem Res. 1985;10:499–513. doi: 10.1007/BF00964654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Mezayen R, El Gazzar M, Seeds MC, McCall CE, Dreskin SC, Nicolls MR. Endogenous signals released from necrotic cells augment inflammatory responses to bacterial endotoxin. Immunol Lett. 2007;31:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esiri MM, Reading MC. Macrophage populations associated with multiple sclerosis plaques. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1987;13:451–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1987.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felts PA, Woolston AM, Fernando HB, Asquith S, Gregson NA, Mizzi OJ, et al. Inflammation and primary demyelination induced by the intraspinal injection of lipopolysaccharide. Brain. 2005;128:1649–66. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson B, Matyszak MK, Esiri MM, Perry VH. Axonal damage in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 1997;120:393–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi M, Rocca MA, Martino G, Horsfield MA, Comi G. Magnetization transfer changes in the normal appearing white matter precede the appearance of enhancing lesions in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:809–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick MJ, Du X, Witte DP, Jirouskova DA, Busuttil SJ, Plow EF, et al. Leukocyte engagement of fibrin(ogen) via the integrin receptor alphaMbeta2/Mac-1 is critical for host inflammatory response in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1596–606. doi: 10.1172/JCI20741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay FW, Drye GW, Dick GWA, Esiri MM. The application of multifactorial cluster analysis in the staging of plaques in early multiple sclerosis: identification and characterization of the primary demyelinating lesion. Brain. 1997;120:1461–83. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.8.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gveric D, Herrera B, Petzold A, Lawrence DA, Cuzner ML. Impaired fibrinolysis in multiple sclerosis: a role for tissue plasminogen activator inhibitors. Brain. 2003;126:1590–8. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung DY, Lee H, Jung BY, Ock J, Lee WH, Suk K. TLR4, but not TLR2, signals autoregulatory apoptosis of cultured microglia: a critical role of IFN-beta as a decision maker. J Immunol. 2005;164:154–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutzelnigg A, Lucchinetti CF, Stadelmann C, Brück W, Rauschka H, Bergmann M, et al. Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:2705–12. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linington C, Bradl M, Lassmann H, et al. Augmentation of demyelination in rat acute allergic encephalomyelitis by circulating antibodies against a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Am J Pathol. 1988;130:443–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti C, Brück W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:707–17. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6<707::aid-ana3>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti CF, Mandler RN, McGavern D, Bruck W, Gleich G, Ransohoff RM, et al. A role for humoral mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Devic’s neuromyelitis optica. Brain. 2002;125:1450–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marburg O. Die sogenannte “akute Multiple Sklerose”. Jahrb Psychiatrie. 1906;27:211–312. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan PA, Doyle TJ, Lai D, Wolinski JS. Serial proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, and quantitative lesion volumetry in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:56–71. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrikios P, Stadelmann C, Kutzelnigg A, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M, Laursen H, et al. Remyelination is extensive in a subset of multiple sclerosis patients. Brain. 2006;129:3165–72. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prineas JW. The neuropathology of multiple sclerosis. In: Koetsier JC, editor. Handbook of clinical neurology. Vol. 47. Elsevier; New York: 1985. pp. 337–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfleisch E. Histologisches Detail zur grauen Degeneration von Gehirn und Rückenmark. Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med (Virchow) 1863;26:474–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schrijver IA, van Meurs M, Melief M-J, Wim-Ang C, Bujevac D, Ravid R, et al. Bacterial petidoglycan and immune reactivity in the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124:1544–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.8.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp FR, Bergeron M, Bernaudin M. Hypoxia-inducible factor in brain. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;502:273–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3401-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp FR, Bernaudin M. HIF1 and oxygen sensing in the brain. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:437–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver NC, Tofts PS, Symms MR, Barker GJ, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. Quantitative contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate blood-barin barrier integrity in multiple sclerosis. A preliminary study. Mult Scler. 2001;7:75–82. doi: 10.1177/135245850100700201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley ST, King JA, Hancock WW. Fibrinogen stimulates macrophage chemokine secretion through toll-like receptor 4. J Immunol. 2001;167:2887–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadelmann C, Ludwin S, Tabira T, Guseo A, Lucchinetti CF, Leel-Össy L, et al. Tissue preconditioning may explain concentric lesions in Balo’s type of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:979–87. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam NJ, Vroom TM, Peters PJ, Pastoors EB, Ploegh HL. HLA-A-and HLA-B-specific monoclonal antibodies reactive with free heavy chains in western blots, in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections and in cryo-immuno-electron microscopy. Int Immunol. 1990;2:113–25. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch MK, Stefferl A, Brehm U, Weissert R, Wallström E, Kerschensteiner M, et al. Autoimmunity to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in rats mimics the spectrum of multiple sclerosis pathology. Brain Pathol. 1998a;8:681–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mork S, Bo L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traugott U, Reinherz EL, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis. Distribution of T cells, T cell subsets and Ia-positive macrophages in lesions of different ages. J Neuroimmunol. 1983;4:201–21. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(83)90036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser L, de Heer H Jan, Boven LA, van Riet D, van Meurs M, Melief MJ, et al. Proinflammatory bacterial peptidoglycan as a cofactor for the development of central nervous system autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:808–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver LK, Pioli PA, Wardwell K, Vogel SN, Guyre PM. Up-regulation of human monocyte CD163 upon activation of cell surface Toll.like receptors. J Leukocyte Biol. 2007;81:663–71. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0706428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuerfel J, Bellmann-Strobl J, Brunecker P, Aktas O, McFarland H, Villringer A, et al. Changes in cerebral perfusion precede plaque formation in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal perfusion MRI study. Brain. 2004;127:111–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.