Abstract

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the colon and rectum. Its pathogenesis is probably multifactorial including the influx of certain cytokines into the colonic mucosa, causing disease activity and relapse. The hypothesis of removing such cytokines from the circulation by leukocytapheresis was implemented to reduce disease activity, maintain remission, and prevent relapse. Many recent reports not only in Japan, but also in the West, have highlighted its beneficial effects in both adult and pediatric patients. Large placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm the available data in this regard. In this article, we shed some light on the use of leukocyte apheresis in the management of autoimmune diseases, especially ulcerative colitis.

Keywords: Cytapheresis, granulocytapheresis, therapy, inflammatory bowel disease, induction of remission

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with a relapsing and remitting course. It affects many individuals worldwide with deleterious effects on the quality of life.[1,2] Many medications, including anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and biological agents, are used to induce and maintain remission without curing the disease and with many side effects.[3,4]

The pathogenesis of UC is ill-understood, and seems to result from a complex interplay between susceptibility genes, environmental factors, and the immune system. Many inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and others are involved.[5,6] The sources of these cytokines are the activated peripheral blood granulocytes which get mobilized first, then infiltrate the colonic mucosa and interact with lymphocytes to orchestrate the inflammatory response and initiate disease activity and/or relapse.[7–10] Therefore, removal of these activated granulocytes by extracorporeal cytapheresis systems, i.e., leukocytapheresis and granulocytapheresis may be a logical therapeutic maneuver.

The goal of this concise report is to present the available data on the efficacy, safety, and applicability of cytapheresis in patients with UC.

DEFINITION

Cytapheresis is an extracorporeal removal of specific cells from the blood using special filters or columns. Due to its ability to remove white blood cells, cytapheresis has been used as a therapeutic modality in many diseases in which sensitized white cells have a pathogenic effect.[11,12] Leukocytapheresis and granulocytapheresis were mainly used in Japan, but over the last decade, they have also attracted much attention in Europe and North America.

SYSTEMS

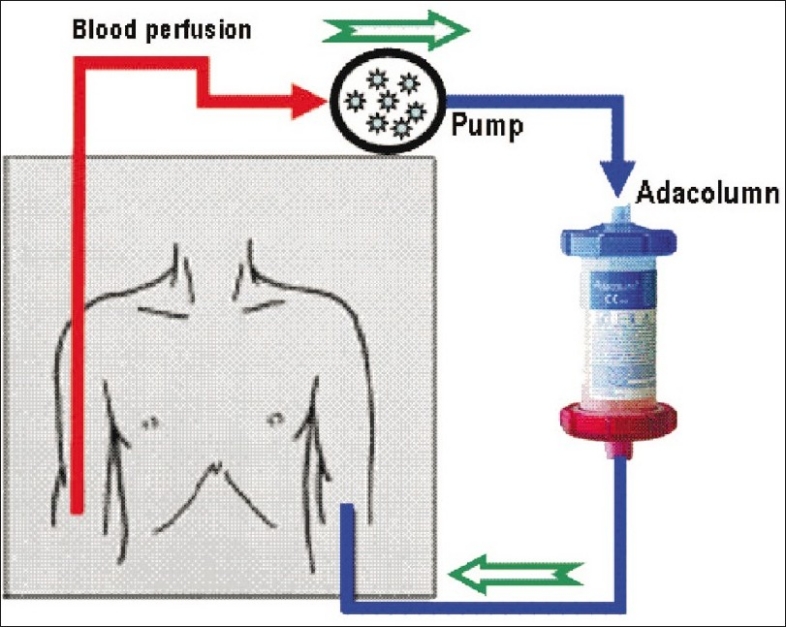

Cellsorba (Asahi Medical, Tokyo, Japan) and Adcolumn (Japan Research Laboratories, Takasaki, Japan, Figure 1) are the commonly used aphesesis systems in the current literature. The whole venous blood is perfused through an adsorption column. The blood is pumped from a peripheral vein in one arm, filtered, and returned to the body via the other arm. A total of 1800 mL blood is filtered over a period of 60 min. The device which uses an Adacolumn filter is preferred over the Cellsorba filter as it selectively removes activated granulocytes and monocytes with no significant change in the number of lymphocytes or platelets.[13]

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the leukocyte apheresis system

CLINICAL USES

The beneficial effect of Adacolumn is related to its ability to reduce numbers of granulocytes, monocytes, and inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8). Additionally, the Adacolumn increases the concentration of circulating immature neutrophils and reduces their ability to secrete such pro-inflammatory cytokines.[14–16] Cytapheresis was first used in Japan for treating patients with leukemia in the 1980s, and is currently used in several autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, and IBD with varying degrees of success [Table 1]. In UC, cytapheresis is indicated in patients with moderately severe cases (steroid-resistant or naïve cases), intractable disease (steroid-dependent), and in severe or fulminant disease.[17]

Table 1.

Common clinical applications* of leukocytapheresis/granulocytapheresis

| Ulcerative colitis |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Behcet's disease |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| ANCA-associated vasculitis |

| Anaphylactoid purpura |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis |

| Crohn's disease |

| Chronic hepatitis C |

| Carcinomas |

| Others |

The list is not exhaustive

ADVANTAGES

The principle of cytapheresis is to remove badly programmed cells instead of adding medications; this explains its relative safety. Cytapheresis does not require shunt operation, as in chronic hemodialysis, does not exacerbate anemia, nor does it influence hemodynamic parameters.[18,19] Each apheresis session lasts for 60 min and can be done in an outpatient setting. Also, it has good tolerability as each treatment course for UC consists of a single session per week for five weeks. In addition, it may improve patients' quality of life.[2] It should be noted that cost-effectiveness has not been studied in this type of patients. Leukopheresis for IBD has not been recommended by US-FDA as first-line or even second-line treatment until now.

DISADVANTAGES

Most of the adverse effects are mild and transient and are attributed to the extracorporeal circulation. These include dizziness, headache, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. In addition, apheresis is a costly procedure compared to other therapeutic modalities. However, it is cost-effective as it reduces the number of hospital admissions, the treatment for steroid-induced side-effects, the need for the expensive biological therapies, and/or the need for surgery.[17]

EFFICACY IN UC

Many studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of cytapheresis in the induction of remission in patients with IBD [Table 2].[19–42] Most of these studies were conducted in small numbers of patients with variable disease severity, and were open-label, uncontrolled studies; a few were randomized.[22,25,33] However, they all supported the effectiveness of cytapheresis in reducing disease activity, achieving clinical remission, and enhancing mucosal healing.

Table 2.

Summary of studies using cytapheresis in treating patients with ulcerative colitis

| Reference | # | UC disease status | Cases # | Apheresis protocol | Side effects % | Efficacy % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimoyama et al. 2001 | 29 | Refractory to conventional drugs | 53 | Standard* | 9 | 21 |

| Tomomasa et al. 2003 | 28 | Steroid-refractory | 12 | Once weekly for 5–10 weeks | 9 | 67 |

| Hanai et al. 2003 | 30 | Steroid-dependent | 31 & 8 | 10-11 sessions in 11 weeks | 18 | 81-88 |

| Suzuki et al. 2004 | 31 | Steroid-naive | 20 | Twice weekly for 3–5 weeks | 10 | 85 |

| Naganuma et al. 2004 | 32 | Steroid-dependent and-refractory | 44 | Standard* | 5 | 55 |

| Hanai 2004** | 33 | Steroid-dependent | 46 | 11 sessions in 10 weeks | 22 | 83 |

| Yamamoto et al. 2004 | 34 | Mild-to-moderate and distal | 30 | Standard* | 27 | 70 |

| Domenech et al. 2004 | 35 | Steroid-dependent | 14 | Standard* | 15 | 62 |

| Kanke et al. 2004 | 36 | Mild-moderate | 60 | 10 sessions in 12 weeks | 18 | 23 |

| Kim et al. 2005 | 37 | Refractory to conventional drugs | 27 | Standard* | 11 | 70 |

| Sawada et al. 2005 | 38 | Moderate-severe | 10 | Standard*plus 2 more sessions in 4 weeks | 10 | 80 |

| Kruis et al. 2005 | 39 | Steroid-dependent | 35 | Standard* | 3 | 37 |

| D'Ovidio et al. 2006 | 40 | Mild-moderate dependent/refractory | 12 | Standard* | 0 | 25$ |

| Ikeda et al. 2006 | 26 | Moderate-severe | 4 | Standard* | - | 50 |

| Sands et al. 2006 | 41 | Moderate-severe | 15 | Standard* | 0 | 33 |

| Okada et al. 2006 | 24 | Moderate-severe | 6 | Once per week for 4 weeks | 17 | 83 |

| Kumagai et al. 2007 | 27 | Recurrent (n = 4) and first attack (n = 1) | 5 | Standard* but at a rate of 50 mL/min | 20 | 60 |

| Bresci et al. 2007 | 21 | Acute | 20 | Standard* | 10 | 70 |

| Takemoto et al. 2007 | 23 | Steroid-refractory | 71 | 1–2 sessions / week for 2–10 weeks | - | 75## |

| Emmrich et al. 2007 | 20 | Refractory to conventional drugs | 20 | Standard* plus 1 session/month for 6 months | - | 70 |

| Ljung et al. 2007 | 19 | Steroid-dependent | 52 | Standard* | 15 | 48 |

| Aoki et al. 2007 | 42 | Moderate-severe | 22 | 2–3 sessions / week, total up to 10 | - | 75 |

| Sakuraba et al. 2008** | 25 | Moderate | 30 | Standard* (n = 15) vs. Intensive (n = 15) | 66.7 vs. 80 | |

| Hanai et al. 2008** | 22 | Moderate-severe U | 35 | Twice weekly × 3 then once up to 11 sessions | 14 | 73.4 |

Standard protocol = 1 session per week for five consecutive weeks, each for 60 min, with blood flow rate of 30 mL/min.

These studies are randomized controlled trial apheresis versus prednisolone. vs. = Versus,

= number,

= Improvement assessed endoscopically,

= in this study only 19 (27%) patients maintained remission for more than 6 months.

Interestingly, cytapheresis in pediatric patients has similar effectiveness in inducing as well as maintaining remission in steroid refractory UC as in adults. This can reduce the serious steroid-induced complications such as growth retardation, infection, and cosmetic effects.[26–28]

REGIMENS

Standard (conventional) course: One session per week for five consecutive weeks.

Intensive course: 2–3 sessions per week in the first two weeks, then once weekly. An intensive cytapheresis course induces rapid remission and is, therefore, a preferred regimen compared to the standard once-weekly course.[25,42]

POTENTIAL ROLE OF PHOTOPHERESIS

Extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) is the ex vivo exposure of apheresed peripheral blood mononuclear cells to ultraviolet A light in the presence of a DNA-intercalating agent such as 8-methoxythoralin (8-MOP), and their subsequent reinfusion. ECP was used initially since the early 1980s in managing malignant and autoimmune diseases including Sezary syndrome, T-cell lymphoma, and graft-versus-host disease.[43–46] In ECP, exposure of circulating immune cells to UVA and 8-MOP induces immunomodulatory changes that lead to tolerance to alloreactive or autoreactive antigen-generated T-cell responses.[47,48] The potential role of ECP in combination with apheresis in patients with IBD has not been tested, and warrants further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

Cytapheresis may offer an adjuvant therapeutic option for inducing and maintaining remission in patients with chronic active UC. It is associated with a low incidence of adverse effects compared to other modalities. Well-designed placebo-controlled trials as definitive proofs of efficacy are currently underway. Also needed are studies addressing optimal treatment schemes, patients who would benefit most from this modality, when to combine it with other therapies such as immunotherapy, and the value of using ECP.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loftus EV., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oxelmark L, Hillerås P, Dignass A, Mössner J, Schreiber S, Kruis W, et al. Quality of life in patients with active ulcerative colitis treated with selective leukocyte apheresis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:406–7. doi: 10.1080/00365520600881060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taffet SL, Das KM. Sulfasalazine. Adverse effects and desensitization. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:833–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01296907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Present DH. How to do without steroids in inflammatory bowel disease? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:48–57. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreiber S, Nikolaus S, Hampe J, Hämling J, Koop I, Groessner B, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 beta in relapse of Crohn's disease. Lancet. 1999;353:459–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03339-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2000;5:1289–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanai T, Makita S, Kawamura T, Nemoto Y, Kubota D, Nagayama K, et al. Extracorporeal elimination of TNF-alpha-producing CD14(dull)CD16(+) monocytes in leukocytapheresis therapy for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:284–90. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikolaus S, Bauditz J, Gionchetti P, Witt C, Lochs H, Schreiber S. Increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by circulating polymorphonuclear neutrophils and regulation by interleukin 10 during intestinal inflammation. Gut. 1998;42:470–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, Fagerhol MK, Bjarnason I. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:15–22. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lügering N, Kucharzik T, Stoll R, Domschke W. Current concept of the role of monocytes/macrophages in inflammatory bowel disease: balance of proinflammatory and immunosuppressive mediators. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:338–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilder RL, Malone DG, Yarboro CH, Berkebile C, Haraoui B, Allen JB, et al. Leukapheresis and pathogenetic mechanisms in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Apher. 1984;2:112–8. doi: 10.1002/jca.2920020118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suemitsu J, Yoshida M, Yamawaki N, Yamashita Y. Leukocytapheresis therapy by extracorporeal circulation using a leukocyte removal filter. Ther Apher. 1998;2:31–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.1998.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohara M, Saniabadi AR, Kokuma S, Hirata I, Adachi M, Agishi T, et al. Granulocytapheresis in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Artif Organs. 1997;2:989–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1997.tb00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saniabadi AR, Hanai H, Takeuchi K, Umemura K, Nakashima M, Adachi T, et al. Adacolumn, an adsorptive carrier based granulocyte and monocyte apheresis device for the treatment of inflammatory and refractory diseases associated with leukocytes. Ther Apher Dial. 2003;7:48–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2003.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanai H, Watanabe F, Saniabadi AR, Matsushitai I, Takeuchi K, Iida T. Therapeutic efficacy of granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis in severe active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2349–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1020159932758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashiwagi N, Sugimura K, Koiwai H, Yamamoto H, Yoshikawa T, Saniabadi AR, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis as a treatment for patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1334–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1015330816364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Safety and clinical efficacy of granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis therapy for ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:520–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyamoto H, Okahisa T, Iwaki H, Murata M, Ito S, Nitta Y, et al. Influence of leukocytapheresis therapy for ulcerative colitis on anemia and hemodynamics. Ther Apher Dial. 2007;11:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2007.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ljung T, Thomsen Oø, Vatn M, Karlén P, Karlsen LN, Tysk C, et al. Granulocyte, monocyte/macrophage apheresis for inflammatory bowel disease: the first 100 patients treated in Scandinavia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:221–7. doi: 10.1080/00365520600979369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emmrich J, Petermann S, Nowak D, Beutner I, Brock P, Klingel R, et al. Leukocytapheresis (LCAP) in the management of chronic active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomized pilot trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2044–53. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9696-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bresci G, Parisi G, Mazzoni A, Scatena F, Capria A. Treatment of patients with acute ulcerative colitis: conventional corticosteroid therapy (MP) versus granulocytapheresis (GMA): a pilot study. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:430–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanai H, Iida T, Takeuchi K, Watanabe F, Maruyama Y, Kageoka M, et al. Intensive granulocyte and monocyte adsorption versus intravenous prednisolone in patients with severe ulcerative colitis: An unblinded randomised multi-centre controlled study. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takemoto K, Kato J, Kuriyama M, Nawa T, Kurome M, Okada H, et al. Predictive factors of efficacy of leukocytapheresis for steroid-resistant ulcerative colitis patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:422–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada H, Takenaka R, Hiraoka S, Makidono C, Hori S, Kato J, et al. Centrifugal leukocytapheresis therapy for ulcerative colitis without concurrent corticosteroid administration. Ther Apher Dial. 2006;10:242–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakuraba A, Sato T, Naganuma M, Morohoshi Y, Matsuoka K, Inoue N, et al. A pilot open-labeled prospective randomized study between weekly and intensive treatment of granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis for active ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:51–6. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikeda H, Ishimaru Y, Takayasu H, Fujino J, Kisaki Y, Otani Y, et al. Efficacy of granulocyte apheresis in pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:592–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000237928.07729.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumagai M, Yamato Y, Maeda K, Nakashima E, Ushijima K, Kimura A. Extracorporeal leukocyte removal therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:431–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomomasa T, Kobayashi A, Kaneko H, Mika S, Maisawa S, Chino Y, et al. Granulocyte adsorptive apheresis for pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:750–4. doi: 10.1023/a:1022892927121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimoyama T, Sawada K, Hiwatashi N, Sawada T, Matsueda K, Munakata A, et al. Safety and efficacy of granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis in patients with active ulcerative colitis: a multicenter study. J Clin Apher. 2001;16:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jca.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanai H, Watanabe F, Takeuchi K, Iida T, Yamada M, Iwaoka Y, et al. Leukocyte adsorptive apheresis for the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a prospective, uncontrolled, pilot study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:28–35. doi: 10.1053/jcgh.2003.50005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki Y, Yoshimura N, Saniabadi AR, Saito Y. Selective granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis as a first-line treatment for steroid naive patients with active ulcerative colitis: a prospective uncontrolled study. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:565–71. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000026299.43792.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naganuma M, Funakoshi S, Sakuraba A, Takagi H, Inoue N, Ogata H, et al. Granulocytapheresis is useful as an alternative therapy in patients with steroid-refractory or -dependent ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:251–7. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanai H, Watanabe F, Yamada M, Sato Y, Takeuchi K, Iida T, et al. Adsorptive granulocyte and monocyte apheresis versus prednisolone in patients with corticosteroid-dependent moderately severe ulcerative colitis. Digestion. 2004;70:36–44. doi: 10.1159/000080079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto T, Umegae S, Kitagawa T, Yasuda Y, Yamada Y, Takahashi D, et al. Granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis in the treatment of active distal ulcerative colitis: a prospective, pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:783–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domènech E, Hinojosa J, Esteve-Comas M, Gomollón F, Herrera JM, Bastida G, et al. Granulocyte aphaeresis in steroid-dependent inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, open, pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1347–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanke K, Nakano M, Hiraishi H, Terano A. Clinical evaluation of granulocyte/monocyte apheresis therapy for active ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:811–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HJ, Kim JS, Han DS, Yang SK, Hahm KB, Lee WI, et al. Granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis in Korean conventional treatment-refractory patients with active ulcerative colitis: a prospective open-label multicenter study. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;45:34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawada K, Kusugami K, Suzuki Y, Bamba T, Munakata A, Hibi T. Leukocytapheresis in ulcerative colitis: results of a multicenter double-blind prospective case-control study with sham apheresis as placebo treatment. th Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1362–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kruis W, Dignass A, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Morgenstern J, Mössner J, Schreiber S, et al. Open label trial of granulocyte apheresis suggests therapeutic efficacy in chronically active steroid refractory ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7001–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i44.7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D'Ovidio V, Aratari A, Viscido A, Marcheggiano A, Papi C, Capurso L, et al. Mucosal features and granulocyte-monocyte-apheresis in steroid-dependent/refractory ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:389–94. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Wolf DC, Katz S, Safdi M, Schwartz DA, et al. Pilot feasibility studies of leukocytapheresis with the Adacolumn Apheresis System in patients with active ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:482–9. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aoki H, Nakamura K, Yoshimatsu Y, Tsuda Y, Irie M, Fukuda K, et al. Adacolumn selective leukocyte adsorption apheresis in patients with active ulcerative colitis: clinical efficacy, effects on plasma IL-8, and expression of Toll-like receptor 2 on granulocytes. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1427–33. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenna KE, Whittaker S, Rhodes LE, Taylor P, Lloyd J, Ibbotson S, et al. Evidence-based practice of photopheresis 1987-2001: a report of a workshop of the British Photodermatology Group and the U.K. Skin Lymphoma Group. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gasová Z, Spísek R, Dolezalová L, Marinov I, Vítek A. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy (ECP) in treatment of patients with c-GVHD and CTCL. Transfus Apher Sci. 2007;36:149–58. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zane C, Venturini M, Sala R, Calzavara-Pinton P. Photodynamic therapy with methylaminolevulinate as a valuable treatment option for unilesional cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:254–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2006.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Couriel DR, Hosing C, Saliba R, Shpall EJ, Anderlini P, Rhodes B, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for the treatment of steroid-resistant chronic GVHD. Blood. 2006;107:3074–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorgun G, Miller KB, Foss FM. Immunologic mechanisms of extracorporeal photochemotherapy in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2002;100:941–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osella-Abate S, Zaccagna A, Savoia P, Quaglino P, Salomone B, Bernengo MG. Expression of apoptosis markers on peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma during extracorporeal photochemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:40–7. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.108376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]