Abstract

Onychophora are ancient, carnivorous soft-bodied invertebrates which capture their prey in slime that originates from dedicated glands located on either side of the head. While the biochemical composition of the slime is known, its unusual nature and the mechanism of ensnaring thread formation have remained elusive. We have examined gene expression in the slime gland from an Australian onychophoran, Euperipatoides rowelli, and matched expressed sequence tags to separated proteins from the slime. The analysis revealed three categories of protein present: unique high-molecular-weight proline-rich proteins, and smaller concentrations of lectins and small peptides, the latter two likely to act as protease inhibitors and antimicrobial agents. The predominant proline-rich proteins (200 kDa+) are composed of tandem repeated motifs and distinguished by an unusually high proline and charged residue content. Unlike the highly structured proteins such as silks used for prey capture by spiders and insects, these proteins lack ordered secondary structure over their entire length. We propose that on expulsion of slime from the gland onto prey, evaporative water loss triggers a glass transition change in the protein solution, resulting in adhesive and enmeshing thread formation, assisted by cross-linking of complementary charged and hydrophobic regions of the protein. Euperipatoides rowelli has developed an entirely new method of capturing prey by harnessing disordered proteins rather than structured, silk-like proteins.

Keywords: velvet worm, disordered proteins, prey capture, proline-rich proteins, lectins, protease inhibitors

1. Introduction

Onychophora, or velvet worms, were among the first ambulatory terrestrial animals on Earth and have existed for around 500 Myr (Ghiselin 1984). They are soft-bodied, multi-legged invertebrates that are found in tropical and temperate rainforest mainly in the Southern Hemisphere. Onychophora are placed in a phylogenetically interesting position and their presence has been central to arguments over the composition of the most significant clade of animals. Onychophora forms a sister group to the Arthropoda, and together, they have been placed in an important monophyletic clade with nematodes and Tardigrada (Ecdysozoa) or have been grouped in the Articulata with annelid worms (Aguinaldo et al. 1997; Roeding et al. 2007; Telford et al. 2008).

One of the curious features of the Onychophora is their method of prey capture: termites and other small invertebrates are trapped in a sticky secretion that originates from dedicated slime glands, a pair of modified limbs located on either side of the head. Prey becomes entangled in the beaded threads of slime and is subsequently immobilized, and then the liquid fraction from the prey animal and slime is consumed following application of salivary enzymes (Heatley 1935; Read & Hughes 1987). The composition of the slime and the mechanism of ensnaring thread formation have fascinated researchers for decades. Theories have ranged from the slime consisting of a solution of primitive silk (Craig 1997) or collagen-like fibres (Benkendorff et al. 1999) that cover and immobilize the prey, to a combination of threads and adhesive droplets similar to that found in orb-weaving spiders (Eisner et al. 1964). Interestingly, the slime is ejected rapidly as a liquid, but once applied to the prey, the animal is almost immediately immobilized in the stiffening gel.

The biochemistry of onychophoran slime has been examined to elucidate the mechanism of prey capture. Benkendorff et al. (1999) analysed the slime from the Australian onychophoran Euperipatoides kanangrensis and found it to be composed of mainly water (90%) with protein making up 55 per cent of the dry mass, and smaller quantities of sugars, lipids and the surfactant nonylphenol. They separated crude slime into a high molecular fraction (greater than 600 kDa) and low-molecular-weight, dimeric proteins of approximately 25 kDa. The large proteins were rich in proline, moderate amounts of glycine and a small fraction of hydroxyproline, which led the researchers to propose that onychophorans produced collagen-like structural fibres. Benkendorff et al. (1999) also suggested that the low-molecular-weight protein fraction was responsible for the adhesive fluid that coats the capture fibres that they and others (Eisner et al. 1964; Ruhberg & Storch 1977) had reported. Many questions around the mechanism of the slime's entangling action and the nature of its very unusual composition remain unanswered.

We have investigated gene expression in the slime gland from an Australian onychophoran, Euperipatoides rowelli, and examined the protein composition of the ejected gland contents. Contrary to previous suggestions that onychophorans use highly structured, fibrous proteins such as silks or collagens for capture, we have discovered that they have evolved a unique set of highly unstructured (disordered) proteins that rapidly form sticky prey capture threads on expulsion from the gland. Other components of the secretion include a range of lectins and small peptides, the latter likely to act as protease inhibitors and antimicrobial agents in the gland. In addition, we propose a plausible mechanism that accounts for the liquid-to-solid transformation of the slime gland secretion.

2. Material and methods

(a). Animals

Onychophora (Eu. rowelli Reid 1996) (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) were obtained from Tallanganda State Forest (New South Wales, Australia) and maintained in enclosed 50 ml plastic containers on dampened peat moss at 10°C in the dark, fed weekly with a diet of young termites.

(b). Slime and tissue collection

Slime gland material was collected by gently squeezing individual onychophorans with forceps or exposing them to short draughts of carbon dioxide while the anterior region of the animal was located in the mouth of a microcentrifuge tube.

The slime gland was dissected from animals immersed in phosphate buffered saline. The posterior and anterior ends of the dissected gland were immediately transferred to separate vials containing RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and stored at 4°C. The proteins present in the gland lumen of some animals were placed in LDS sample loading buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) including reductant (10% NuPage reducing agent, Invitrogen) and stored at −20°C for subsequent protein analysis.

(c). cDNA library construction

Total RNA (25 µg) was isolated from the slime gland of 10 onychophorans using the RNAqueous for PCR kit from Ambion. mRNA was isolated from the total RNA using the Micro-FastTrack 2.0 mRNA Isolation kit from Invitrogen according to the manufacturer's directions. No measurable levels of mRNA were detected in samples from the anterior (lumen) end of the slime gland, suggesting that protein expression in this area of the gland is significantly reduced in comparison to expression in the posterior end. A slime gland cDNA library was constructed from the mRNA from the posterior end of the gland using the CloneMiner cDNA library construction kit from Invitrogen, as described by Sutherland et al. (2006). The library comprised approximately 1.3 × 107 colony forming units with an average insert size of around 1 Kbp. Expressed sequence tags (ESTs) were obtained from approximately 850 bp from the 5′ end of 96 randomly selected cDNA clones using the GenomeLab DTCS Quick start kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) and a CEQ8000 BioRad sequencer. Further sequence data were obtained from cDNA over 800 bp by primer walking using oligonucleotide primers designed to internal sequences.

(d). Gene and protein sequence analysis

Nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994) with minor manual adjustments to achieve in-frame nucleotide sequences. The predicted amino acid sequences of the onychophoran ESTs were analysed by BLASTp and tBLASTn (Altschul et al. 1997) at the NCBI server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) against the non-redundant and EST databases, respectively.

Calculation of molecular weights and isoelectric points of encoded proteins were performed using ProtParam, package available from the ExPASy server (www.expasy.org), and secondary structures were detected using PROFSEC and NORS, both part of the PredictProtein package (Rost et al. 2004). Disordered regions were predicted using DISOPRED2 (Ward et al. 2004) and IUPred (Dosztanyi et al. 2005) and repeated regions within protein sequences were detected using the RADAR program (Heger & Holm 2000). Signal peptides were predicted by SignalP 3.0 (Bendtsen et al. 2004) and Wolf-PSORT (http://www.wolfpsort.seq.cbrc.jp) algorithms. Amino acids potentially subject to O-glycosylation were predicted using oGPET 1.0 (http://ogpet.utep.edu/OGPET/index.php), and N-glycosylation was predicted using NetNGlyc 1.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/).

Accession numbers for key genes from Eu. rowelli are: Er_P1 HM217027; Er_P2aHM217028; Er_P2b HM217029; Er_P3 HM217030; Er_Lec1 HM217031; Er_Lec2 HM217032; Er_Lec3 HM217033; Er_Lec4 HM217034; Er_Pep1 HM217035; Er_Pep2 HM217036; Er_Pep3 HM217037; Er_Pep4 HM217038; Er_Pep5 HM217039; Er_Pep6 HM217040; Er_ProtA HM217041; Er_ProtB HM217042.

(e). Slime treatments

The ejected slime was either left untreated in a capped Eppendorf tube, mixed with 60 or 350 µl of milli-Q water or 2 per cent w/v sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). To help elucidate the mechanism of slime setting, a range of substances were added to the onychophoran slime stored in an eppendorf tube and any effect on gelation was visually monitored and changes in the proteins were analysed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and detected by Coomassie Blue staining. The treatments included separation of the slime components by centrifugation through a size-selective membrane (50 kDa), separate additions of synthetic sea water (35 g l−1 sodium chloride), 20 mM disodium EDTA, 10 mM reduced glutathione, 20 mM 1,10-phenanthroline in 100 mM Tris buffer pH 7.5, 3 mM phenylmethyl sulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) added in isopropanol and 5 per cent acetic acid (vol/vol%). In addition, a sample of liquid onychophoran slime was transferred from an eppendorf tube onto a glass plate while within an anaerobic chamber and the setting behaviour of the slime was observed.

(f). Protein separation and identification

Slime gland protein samples were separated by SDS–PAGE on 3–8% Tris–acetate gradient gels to separate high-molecular-weight proteins and 4–12% Bis–Tris gradient gel for low-molecular-weight proteins (Invitrogen) under both reducing and non-reducing conditions. Protein bands were visualized using Coomassie B blue staining.

Stained protein bands were cut out of the gels, digested with trypsin and the resultant peptides were analysed by reversed-phase liquid chromatography coupled by electrospray ionization ion trap tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) as described previously (Sutherland et al. 2006). Mass spectral datasets were analysed using SpectrumMill software (Agilent Technologies) to match the tryptic peptides against predictions of protein sequences (in all six frames) from the onychophoran slime gland cDNA library. Matches between the predicted EST sequences and digested protein fragments were based on at least two peptide matches within the protein and scores greater than 20 (the default setting of the SpectrumMill software for confident identification).

Relative intensity measurements were made for onychophoran slime proteins separated by SDS–PAGE and stained with Coomassie B250 blue dye. After gels were scanned, quantitative intensity analysis was performed within each lane using the program ImageQuantTL (GE Heathcare). Relative protein intensities were averaged for protein classes in four replicate lanes.

(g). Slime protein structure analysis

The threads prepared from the slime gland secretion were examined using a Bruker Tensor 37 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer with a Pike Miracle diamond attenuated total reflection accessory. The amide I and II regions of the spectrum were examined to identify secondary structure characteristics. Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) analysis of the thread is described in the electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

(a). Ejected slime rapidly forms solid threads lacking ordered structure

Liquid onychophoran slime ejected from a slime gland onto a glass or plastic surface adhered and set into a clear solid within a few seconds to a minute. However, while still liquid, slime could also be drawn into a thread by extending the fluid under low tension (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). The material underwent a change during drying from a viscous fluid that was easily stretched into a stiff thread that could be fractured under force. When liquid, slime threads were highly adhesive and attached themselves to a wide array of materials including polypropylene tubes, insect cuticle, keratin, glass and metal surfaces. Once threads had dried, they were no longer adhesive and were insoluble in water, or in the following protein denaturing and chaotropic reagents: urea (6 M), lithium bromide (20 mM) or SDS (2% w/v).

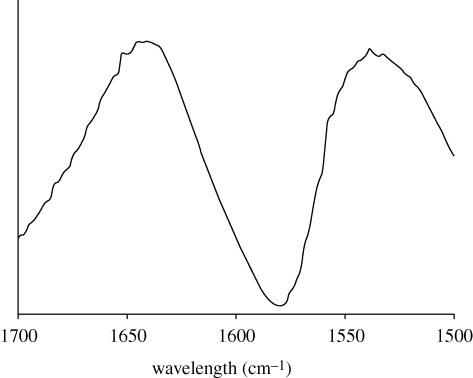

Fourier transform-infrared analysis of the amide I and II regions of the dried slime threads showed broad peaks, indicating a mixture of protein secondary structures (figure 1). The maxima of the spectrum were at 1641 cm−1 in the amide I region and 1539 cm−1 in the amide II region, suggesting proteins that are rich in random coil conformation (Pelton & McLean 2000). The proteins within the threads apparently lack long-range order as no pattern was revealed by WAXS analysis (electronic supplementary material, figure S3), in contrast to the well-defined scattering patterns obtained from the highly ordered structures of silk threads examined under identical experimental conditions (Weisman et al. 2009).

Figure 1.

Fourier transform-infrared spectrum of dried threads drawn from onychophoran slime. The broad peak in the amide I region is centred at 1641 cm−1, a characteristic position for random coil protein structure. No distinct peaks are detected in the 1650–1655 cm−1 range (characteristic of α-helices) or the 1625–1635 cm−1 range (characteristic of β-sheets).

(b). Three classes of proteins make up the major slime components

A cDNA library was constructed from the slime glands of 10 animals and ESTs from 82 clones returned good-quality sequence data. EST sequence length was supplemented by primer walking to obtain full sequence from representative cDNA.

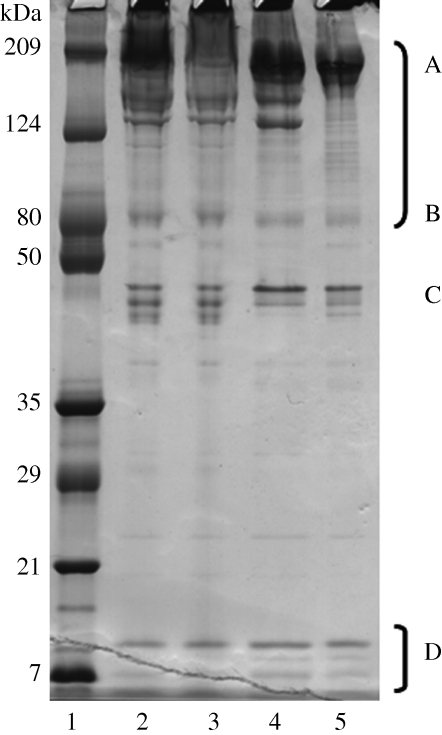

Slime gland proteins were separated under reducing, denaturing electrophoresis conditions. There were at least three low-molecular-weight bands (7–10 kDa), at least three moderately stained molecular weight bands (45–49 kDa), a diffuse band at 80 kDa, two high-molecular-weight bands at 150–180 kDa and a prominent band at approximately 210 kDa (figure 2). Coomassie Blue staining indicated the high-molecular-weight proteins comprised the majority of the slime; as the dye binds by physisorption to arginine, aromatic amino acids and histidine and the onychophoran high-molecular-weight proteins are deficient in hydrophobic amino acids compared with globular proteins, it is unlikely that these proteins have been overestimated. In a separate experiment, slime proteins from eight individual Onychophora from two regions of Tallanganda State Forest were analysed by SDS–PAGE, but no variation in protein band and number was observed between them (data not shown).

Figure 2.

SDS–PAGE separation of four different onychophoran slime samples (lanes 2–5). The apparent molecular weights for proteins are indicated by markers (lane 1). Some slime proteins were identified by peptide mass sequencing and cross-reference to the slime gland cDNA library such as the (A) high-molecular-weight (B) mid-molecular-weight proline-rich proteins and (D) lectin classes of protein. The proteins at (C) were not identified.

Analysis of the encoded proteins of the 82 EST sequences and confirmation by peptide LC-MS/MS analysis indicated the presence of three major classes of encoded protein in the onychophoran slime: proline-rich proteins, lectins and small peptides, in addition to housekeeping proteins. A summary of EST distribution, properties and matches to slime proteins is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the properties of EST isolated from a slime gland cDNA library and the abundance of the encoded proteins within the slime gland. n.d., not detected.

| protein category | EST name and mean length | frequency of ESTs in category | range of encoded protein sizes from ESTsb (kDa) | match to protein band (kDa) after LC-MS/MS detection | number of peptide matches in LC-MS/MS analysis | identification score in LC-MS/MS (>20 is confident) | relative intensity (%) of Coomassie staining of protein on SDS–PAGEc | length of predicted secretion signal peptide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proline-rich | Er_P1 (>4.5 kba) | 7 | a | 230, 350 | 6 | 53 | 71 | a |

| Er_P2 (1.6 kb) | 13 | 55–66 | 80, 90 | 15 | 222.7 | 5 | 1–16; 1–24 | |

| Er_P3<800 bp | 7 | 17.7 | n.d. | n.d. | 1–18 | |||

| carbohydrate binding | Er_Lec1 | 5 | 13.7 | 11, 13 | 4 | 52.1 | 9 | 1–25 |

| Er_Lec2 | 3 | 10.6 | 1–25 | |||||

| Er_Lec3 | 4 | 11.5 | 1–22 | |||||

| Er_Lec4 | 1 | 11.3 | 1–22 | |||||

| Er_Lec5 | 1 | 28.5 | 1–19 | |||||

| antimicrobial peptides | Er_Pep;Er_Prot | 37 | 2.5–11 | n.d. | n.d. | range | ||

| unidentified gel protein | no match | — | 40–50 | — | 15 | — |

aFull-length sequence was not obtained for this class.

bEncoded mature protein with secretion signal peptide removed.

cSee §2.

(i). Proline-rich proteins

Of highest abundance in the slime gland (figure 2) were proteins containing high levels of proline (9.9–20 molar%). Although cDNA for these proteins comprised 33 per cent of the ESTs analyses, this number does not represent the abundance of the actual message in the cDNA library as the library construction method generates a strong bias for shorter sequences. The majority of the proline-rich proteins were greater than 200 kDa, implying mRNA of greater than 6 kbp—a size too large to be easily transformed into Escherichia coli. The high-proline-containing proteins fell into three distinctive categories based on size, sequence and protein characteristics and each are described below.

The first group consisted of high-molecular-weight homologous proteins; the largest EST and primer walking contig in this category encoded approximately 135 kDa of protein sequence and matched closely to the MS/MS sequence obtained from the strong greater than 200 kDa SDS–PAGE band (table 1). tBLASTn analysis of the encoded sequences matched to translated sequences from whole adults of an unidentified species of the onychophoran Epiperipatus sp. (AM499986, AM498952, AM499414, AM500617; Roeding et al. 2007). There was considerable variability between sequences from the two onychophoran species, for example, amino acid identities between Er_P1 and AM49852 were 37 per cent over the region of sequence match; however, proline residues made up one-third of the conserved residues between the sequences.

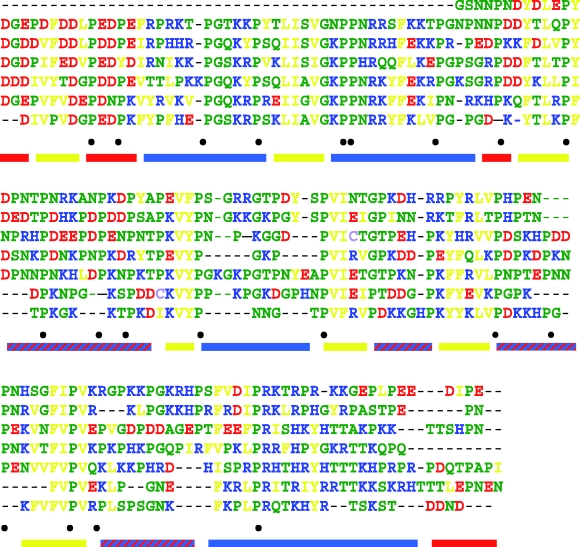

The amino acid compositions of the predicted protein fragments from Er_P1 and six orthologues identified in this study contained high amounts of proline (20%) and charged residues (32%), and were under-represented in hydrophobic residues compared with an average amino acid composition for globular proteins (Tompa 2002). Structural predictions for these sequences found the proteins to be disordered throughout, with no helical or β-sheet formation, and low likelihood of glycosylation (table 2). The proteins were composed of long and imperfect tandem repeated units that cover most of the sequence (figure 3). The repeated units contained a pattern of consecutive charged residues interspersed with short hydrophobic regions.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary structural characteristics of the mature forms of major proline-rich slime proteins of the onychophoran Eu. rowelli. n.d., not detected.

|

Eu. Rowelli slime proteins |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| characteristic | Er_P1 | Er_P2a | Er_P2b | Er_P3 |

| encoded size (kDa) | not obtained in full length | 56.2 | 64.2 | 15.7 |

| match to SDS–PAGE protein band (kDa) | 230, 350 | 80 | 80 | n.d. |

| predicted pI | 9.76 | 5.75 | 9.00 | 5.3 |

| proline (mol%) | 20.0 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 11.9 |

| random coil content (%, PROFsec) | 91.3 | 74.6 | 69.5 | 95.4 |

| sequence disorder predictiona | full length except N-terminus | between residues 155–373 | between residues 185–373 | full lengthb |

| helical regions (PROFsec, probability ≥5) | none | 433–440, 465–476 | 464–466, 566–570 | none |

aPrediction based on NORS regions, DISOPRED2 and IUPred programs.

bIUPred program does not predict any disordered regions in this sequence.

Figure 3.

Aligned tandem repeated regions of the high-molecular-weight proline-rich protein fragment (encoded by Er_P1) from Eu. rowelli demonstrating the conservation of amino acid sequence and character within the sequence. Residue colours: red, acidic D, E; blue, basic K, R, H; yellow, hydrophobic V, L, I, F, Y; green, small and polar N, T, P, S, G, A, Q, glutamine; purple, low frequency C, w between repeats. Conserved proline residues are indicated (•) below the aligned sequences. Coloured bars represent the average character of the segment at neutral pH: red, negatively charged; blue, positively charged; yellow, hydrophobic.

The second group of proline-rich proteins identified corresponded to a set of homologous proteins between 54.8 and 65.8 kDa (481–578 amino acids), having between 52 and 97 per cent exact match between amino acids in the aligned sequences (% identity) and each containing a putative secretion signal at the N-terminus (Er_P2; table 1). The encoded Er_P2 proteins matched strongly to the protein sequence obtained from the 80 and 90 kDa bands on SDS–PAGE (table 1). Across the six full-length sequences, 39.8 per cent of residues are absolutely conserved, with 14.8 per cent of this subset being proline residues. The primary sequence of these proteins had low sequence complexity, but no absolute repeat regions. The Er_P2 proteins had moderately high proline and charged/polar residues and slightly lower hydrophobic residues compared with globular proteins (Tompa 2002) and no predicted glycosylation sites. Er_P2b was unusual in having a predicted basic pI, whereas the other related sequences were acidic–neutral. According to protein structure prediction programmes, these proteins are structured around the N- and C-termini with an extended disordered central region (approx. 188 residues; table 2). While there were no matches between the mid-proline-containing proteins from Eu. rowelli to proteins in the non-redundant database of NCBI, several matches to ESTs from Epiperipatus sp. were located (AM499359, AM499737, AM500552) having around 40 per cent overall identity, although containing regions of perfect match in the translated sequence.

The third group of high-proline proteins (Er_P3) was represented by seven full-length copies of cDNA encoding a 17.7 kDa (152 amino acid) acidic, moderate proline-containing protein with high content of charged and hydrophobic residues and putative secretion signal (tables 1 and 2). These proteins were not detected by LC-MS/MS analysis of Coomassie blue-stained proteins, but this may be due to the lack of suitable peptides generated during trypsin cleavage. Much of the sequence was composed of 11 tandem repeats of the motif PREVVYDR (and variants). Secondary structure predictions of the sequence suggest almost complete random coil for the mature protein, but various protein disorder prediction programmes gave contradictory results; DISOPRED2 predicted a highly disordered protein but IUPred did not. No O- or N-glycosylation sites were predicted in the protein. BLAST searching with the Er_P3 sequence gave spurious matches to many proline-rich repetitive proteins.

(ii). Carbohydrate-binding proteins

Also abundant with 14 copies in the cDNA library were sequences encoding cysteine-rich proteins with high homology to several families of lectins and carbohydrate-binding proteins. All sequences obtained in full length had secretion signal peptide motifs (Er_Lec1-5; table 1). Details about the nature of the carbohydrate-binding proteins and sequence matches to proteins in NCBI are given in the electronic supplementary material.

(iii). Small secreted peptides

We also identified a high frequency of sequences that encoded small peptides (14 kDa and more) in the cDNA library and all had N-terminal secretion signal peptides in the predicted peptide sequence (table 1). Of these, eight were most similar to protease inhibitors (e.g. Er_ProtA and Er_ProtB) and the other 28 ESTs encoded six groups of small peptides (less than 6 kDa for mature peptide; e.g. Er_Pep1-6) with no identified conserved domains. Further features of the peptides and sequence matches to other proteins are detailed in the electronic supplementary material.

(c). Effect of additives on the gelling mechanism of slime

In contrast to the rapid setting of onychophoran slime when ejected into the open environment, slime released directly into an Eppendorf tube, and immediately sealed, remained liquid for at least 1 h. In addition, slime that was ejected directly into a tube containing water or 50 mM Tris buffer readily dissolved and the aqueous solution remained unchanged by observation and SDS–PAGE analysis over 4 days at neutral and slightly basic pH. Separations of diluted slime via a size-selective membrane resulted in the setting of the high-molecular-weight fraction in the upper well of the filter cup. Slime samples that were diluted with 5 per cent acetic acid were rapidly degraded, as demonstrated by loss of protein bands above 100 kDa and the appearance of multiple new bands in the region 30–100 kDa in SDS–PAGE analysis. LC/MS/MS analysis of the lower molecular weight fragments confirmed these were breakdown products of the high-molecular-weight proteins.

Dilution of fresh slime into purified water or treating the slime with synthetic sea water, metal chelation agents (20 mM EDTA), reducing (10 mM glutathione) or zinc-binding (20 mM phenanthroline) conditions made no difference to the appearance of slime solutions, that is, no protein aggregation, viscosity or colour change, nor was there any observed difference in the pattern of proteins by SDS–PAGE analysis (data not shown). The speed and nature of the slime allowed to set within an anaerobic chamber was no different from that in air. However, the addition of isopropanol to an aqueous solution of slime (approx. 10% v/v of final volume), which was used as vehicle for the protease inhibitor PMSF, caused immediate setting of the slime into an insoluble rubber-like substance that could not be drawn up by pipette. PMSF itself did not cause any change in the slime solution.

4. Discussion

(a). The dominant slime proteins are intrinsically unstructured

The majority of the protein component of Eu. rowelli slime was of high molecular weight (figure 3) and proline-rich. The character of the predicted amino acid composition of Er_P1 proteins compared favourably with the measured content of the high-molecular-weight fraction from Eu. kanangrensis slime (Benkendorff et al. 1999; electronic supplementary material, figure S4), although Er_P1 had half its reported glycine content. The amino acid sequence of both high- and mid-molecular-weight high-proline proteins is predicted to lead to intrinsic disorder of the protein structure in solution, a prediction that is supported by structural analysis of the slime threads. The proline-rich proteins of onychophoran slime are unique; unusual in being disordered over the full length of the high- and low-molecular-weight proline-rich proteins and a large proportion of the mid-proline-rich group.

Disordered proteins lack the α-helix and β-sheet secondary structures that form the basis of structure in globular and structural proteins (Tompa 2002). Instead they adopt open, extended and random conformations that have large surface areas and high solvent accessibility (Uversky et al. 2000; Tompa 2005). The extended conformation is maintained by the repulsive forces generated by the many charged amino acids combined with a low content of hydrophobic residues. The amino acid sequences of the high-proline-containing group deliver large tracts of positively or negatively charged residues interspersed with conserved proline residues and short stretches of dispersed hydrophobic residues as shown in figure 3. The low hydrophobicity of the protein prevents the formation of buried core of residues which are the basis of protein structure or aggregation.

Owing to their linear conformation, disordered proteins present a large face for binding to other molecules and many binding-associated roles have been elucidated for them, including transcriptional co-activators, binding effectors for DNA and haeme, scavengers of metal cation, toxicants and water (Tompa 2002, 2005; Dyson & Wright 2005; Meszaros et al. 2007). In particular, the onychophoran proteins share attributes with the mammalian proline-rich salivary proteins, which make up approximately 70 per cent of the proteins in human saliva (Kauffman et al. 1993).

The onychophoran slime proteins are composed of imperfect tandemly repeated motifs. Such motifs are widespread in eukaryotic proteins—it is estimated that approximately 14 per cent of proteins have a repetitive region within them (Marcotte et al. 1999)—and are often associated with structured, fibre-forming proteins such as silk or collagen where the amino acid identity is constrained by conformational requirements of the final structure (Okada et al. 2008; Weisman et al. 2009). Although intrinsic non-structure is determined by the character of the protein sequence rather than a specific motif, tandemly repeated motifs in unstructured regions within proteins have been previously identified (Liu et al. 2002; Tompa 2003). The conservation of amino acid sequence repeat within the high-molecular-weight proline-rich slime protein and between onychophoran species implies either a role for the sequence in the function of the protein aside from maintaining disorder, or that recent gene fragment duplication events have contributed to the presence of the repeated motifs.

(b). The onychophoran slime gland also produced numerous small peptides and lectins

EST sequences for small peptides with homology to protease inhibitors, antimicrobial peptides and lectins were abundant in the onychophoran slime gland cDNA library. Most unstructured proteins are highly susceptible to proteolysis (Tompa 2005) both because of their biased amino acid content (Rechsteiner & Rogers 1996) and open configuration that exposes many residues to attack from proteases. As the slime reserve is built up and stored within the gland, prevention of proteolysis by invading bacteria would be necessary and this may be the major role of the putative protease-inhibiting small peptides identified in the slime gland secretion. Constitutive expression of lectins in salivary glands has been less commonly reported, although they are well known to be part of the antimicrobial secretions in fish skin mucus, and in combination with a cystatin, to protect foam nests for incubating eggs and sperm produced by the tungara frog (Fleming et al. 2009).

(c). Mechanism of prey capture

Prey capture by Onychophora is energetically and nutritionally expensive by virtue of the large amount of protein involved (Read & Hughes 1987) and therefore is required to be effective. The mechanism is reliant on the prey becoming immobilized by the slime secretion. Two major mechanisms for production of strong gels or adhesives from relatively dilute biological protein solutions have been described—entanglement and cross-linking (Smith 2002). Entanglement occurs when giant (greater than 1 MDa), heavily glycosylated proteins in solution at 1 per cent or less (by weight) entangle to an extent that they cause gelation (Doi & Edwards 1988). Onychophoran slime proteins are unlikely to function in this manner as they are only lightly glycosylated, if at all, and are present as viscous fluids in the glands. Cross-linking mechanisms may involve covalent, ionic and/or hydrophobic bonds, with the strength of gelation determined by the number and strength of the cross-links (Smith 2002). For example, mussel byssus plaques use the modified amino acid 3,4-dihydroxyphenolalanine to covalently link foot proteins (Waite & Tanzer 1981). Röper (1977) suggested disulphide bonds across protein strands were responsible for the onychophoran slime's sticky and elastic properties. However, the very low cysteine content of the major slime proteins (0–0.7%) and the lack of effect of reducing agents such as glutathione on slime gelation challenge this hypothesis. Onychophoran slime setting was also unaffected by metal ion chelators and scavengers, which eliminates a role for metal ion-induced cross-linking, whereas maintaining the hydration of liquid slime prevented thread formation.

We propose that Onychophoran gelation occurs through a mechanism assisted by a cross-linking between complementarily charged residues and between short hydrophobic domains of the dominant proteins. In a solution, the large surface area of the proteins is fully hydrated and the proteins are maintained in a soluble state. Upon dehydration of the protein solution by evaporative water loss, regions of opposite charge and hydrophobicity in the protein strands may be brought in closer proximity to enable ionic or hydrophobic–hydrophobic bonds to form. Of the classes of protein-based invertebrate gels and adhesives investigated to date (Smith 2002; Graham 2008), onychophoran slime appears to be unique in terms of components and mechanism of gelation.

Based on the composition of the onychophoran slime and observations of the attack process, we propose the following model for prey capture. The aqueous solution of highly hydrated, disordered proteins (3–5%) is released from the animal in a steady jet. The initial liquid nature of the slime (90% water content; Benkendorff et al. 1999) combined with the force with which the jet is ejected causes the slime to spread over the prey on impact. The presence of lipids and surfactant (Benkendorff et al. 1999) in the slime allows good wetting of the waxy insect cuticle. The struggles of prey insects appear to provide the shear forces necessary to draw threads and we have found experimentally that threads can readily be pulled from fresh slime solutions. Hydrated disordered slime proteins can behave like amorphous polymers that undergo a glass transition into strong and brittle solids in response to temperature changes or removal of plasticizers such as water. As glass transition temperature rises with molecular weight (Fox & Flory 1950; Couchman 1979), the onset of glass transition in the onychophoran slime would occur at higher water content than observed for elastin (molecular weight 66 kDa) whose glass transition temperature graph intersects with the ambient temperature at approximately 25 per cent water content (Grunina et al. 2006). In the case of the onychophoran slime, thread formation may be promoted by protein cross-linking, and concurrent with the glass transition process.

The onychophoran Eu. rowleii has developed an entirely new method of capturing prey using unique proteins that are highly soluble and easily ejected from the storage gland but when surface area and evaporative water loss rate are increased, they rapidly convert to adhesive and enmeshing threads as complementary regions in disordered proteins are brought together by non-covalent cross-linking.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Crop Biofactories Initiative, a joint venture of CSIRO and the Australian Grains Research & Development Corporation, and thank Drs James Woodman and Andreas Zwick for collection of the onychophorans and advice on rearing. Dr Stephen Mudie of the Australian Synchrotron is thanked for assistance with WAXS analysis and Dr Matt Taylor for his helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- Aguinaldo A. M. A., Turbeville J. M., Linford L. S., Rivera M. C., Garey J. R., Raff R. A., Lake J. A.1997Evidence for a clade of nematodes, arthropods and other moulting animals. Nature 387, 489–493 (doi:10.1038/387489a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaeffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J.1997Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 (doi:10.1093/nar/25.17.3389) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen J. D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S.2004Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkendorff K., Beardmore K., Gooley A. A., Packer N. H., Tait N. N.1999Characterisation of the slime gland secretion from the peripatus, Euperipatoides kanangrensis (Onychophora: Peripatopsidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 124, 457–465 (doi:10.1016/S0305-0491(99)00145-5) [Google Scholar]

- Couchman P. R.1979The effect of molecular weight on glass-transition temperatures (compositional variation of glass-transition temperatures 3). J. Appl. Phys. 50, 6043–6046 (doi:10.1063/1.325792) [Google Scholar]

- Craig C. L.1997Evolution of arthropod silks. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 42, 231–267 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.231) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi M., Edwards S. F.1988The theory of polymer dynamics. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press [Google Scholar]

- Dosztanyi Z., Csizmok V., Tompa P., Simon I.2005IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 21, 3433–3434 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson H. J., Wright P. E.2005Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. 6, 197–208 (doi:10.1038/nrm1589) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner T., Alsop R., Ettershank G.1964Adhesiveness of spider silk. Science 146, 1058–1061 (doi:10.1126/science.146.3647.1058) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R. I., Mackenzie C. D., Cooper A., Kennedy M. W.2009Foam nest components of the tungara frog: a cocktail of proteins conferring physical and biological resilience. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 1787–1795 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1939) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox T. G., Jr, Flory P. J.1950Second-order transition temperatures and related properties of polystyrene. I. Influence of molecular weight. J. Appl. Phys. 21, 581–591 (doi:10.1063/1.1699711) [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselin M. T.1984Peripatus as a living fossil. In Living fossils (eds Eldredge N., Stanley S. M.), pp. 214–217 New York, NY: Springer-Verlag [Google Scholar]

- Graham L. D.2008Biological adhesives from nature. In Encyclopedia of biomaterials and biomedical engineering, 2nd edn (eds Wnek G., Bowlin G.), pp. 236–253 New York, NY & London, UK: Informa Healthcare [Google Scholar]

- Grunina N. A., Belopolskaya T. V., Tsereteli G. I.2006The glass transition process in humid biopolymers. DSC study. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 40, 105–110 (doi:10.1088/1742-6596/40/1/013) [Google Scholar]

- Heatley N. G.1935The digestive enzymes of the Onychophora (Peripatopsis spp.). J. Exp. Biol. 8, 329–343 [Google Scholar]

- Heger A., Holm L.2000Rapid automatic detection and alignment of repeats in protein sequences. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 41, 224–237 (doi:10.1002/1097-0134(20001101)41:2<224::AID-PROT70>3.0.CO;2-Z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman D. L., Keller P. J., Bennick A., Blum M.1993Alignment of amino acid and DNA sequences of human proline-rich proteins. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 4, 287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Tan H., Rost B.2002Loopy proteins appear conserved in evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 53–64 (doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00736-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte E. M., Pellegrini M., Yeates T. O., Eisenber D. A.1999Census of protein repeats. J. Mol. Biol. 293, 151–160 (doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3136) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meszaros B., Tompa P., Simon I., Dosztanyi Z.2007Molecular principles of the interactions of disordered proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 549–561 (doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S., Weisman S., Trueman H. T., Mudie S. T., Haritos V. S., Sutherland .T. D.2008Australian webspinners make finest known insect silk fibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 43, 271–275 (doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2008.06.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelton J. T., McLean L. R.2000Spectroscopic methods for analysis of protein secondary structure. Anal. Biochem. 277, 167–176 (doi:10.1006/abio.1999.4320) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read V. M. S. J., Hughes R. N.1987Feeding behaviour and prey choice in Macroperipatus torquatus (Onychophora). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 230, 483–506 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1987.0030) [Google Scholar]

- Rechsteiner M., Rogers S. W.1996PEST domains: sequence and regulation by proteolysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21, 267–271 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeding F., Hagner-Holler S., Ruhberg H., Ebersberger I., von Haeseler A., Kube M., Reinhardt R., Burmester T.2007EST sequencing of Onychophora and phylogenomic analysis of Metazoa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 45, 942–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röper H.1977Analytical investigations on the defensive secretions from Peripatopsis moseleyi (Onychophora). Z. Naturforsch. C 32, 57–60 [Google Scholar]

- Rost B., Yachdav G., Liu J.2004The PredictProtein Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W321–W326 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkh377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhberg V. H., Storch V.1977Uber Wehrdrusen und Wehrsekret von Peripatopsis moseleyi (Onychophora) Elektronenmikroskopische Untersuehungen und Lebendbeobachtungen. Zool. Anz. (Jena) 198, 9–19 [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. M.2002The structure and function of adhesive gels from invertebrates. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 1164–1171 (doi:10.1093/icb/42.6.1164) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland T. D., Campbell P. M., Weisman S., Trueman H. E., Sriskantha A., Wanjura W. J., Haritos V. S.2006A highly divergent gene cluster in honey bees encodes a novel silk family. Genome Res. 16, 1414–1421 (doi:10.1101/gr.5052606) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telford M. J., Bourlat S. J., Economou A., Papillon D., Rota-Stabelli O.2008The evolution of the Ecdysozoa. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 1529–1537 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2243) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J.1994Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (doi:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P.2002Intrinsically unstructured proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 275, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P.2003Intrinsically unstructured proteins evolve by repeat expansion. Bioessays 25, 847–855 (doi:10.1002/bies.10324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P.2005The interplay between structure and function in intrinsically unstructured proteins. FEBS Lett. 579, 3346–3354 (doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.072) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V. N., Gillespie J. R., Fink A. L.2000Why are ‘natively unfolded’ proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 41, 415–427 (doi:10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::AID-PROT130>3.0.CO;2-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite J. H., Tanzer M. L.1981Polyphenolic substance of Mytilus edulis: novel adhesive containing L-DOPA and hydroxyproline. Science 212, 1038–1040 (doi:10.1126/science.212.4498.1038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. J., Sodhi J. S., McGuffin L. J., Buxton B. F., Jones D. T.2004Prediction and functional analysis of native disorder in proteins from the three kingdoms of life. J. Mol. Biol. 337, 635–645 (doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman S., Okada S., Mudie S. T., Huson M. G., Trueman H. E., Sriskantha A., Haritos V. S., Sutherland T. D.2009Fifty years later: the sequence, structure and function of lacewing cross-beta silk. J. Struct. Biol. 168, 467–475 (doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2009.07.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]