Abstract

Social organisms are constantly exposed to infectious agents via physical contact with conspecifics. While previous work has shown that disease susceptibility at the individual and group level is influenced by genetic diversity within and between group members, it remains poorly understood how group-level resistance to pathogens relates directly to individual physiology, defence behaviour and social interactions. We investigated the effects of high versus low genetic diversity on both the individual and collective disease defences in the ant Cardiocondyla obscurior. We compared the antiseptic behaviours (grooming and hygienic behaviour) of workers from genetically homogeneous and diverse colonies after exposure of their brood to the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. While workers from diverse colonies performed intensive allogrooming and quickly removed larvae covered with live fungal spores from the nest, workers from homogeneous colonies only removed sick larvae late after infection. This difference was not caused by a reduced repertoire of antiseptic behaviours or a generally decreased brood care activity in ants from homogeneous colonies. Our data instead suggest that reduced genetic diversity compromises the ability of Cardiocondyla colonies to quickly detect or react to the presence of pathogenic fungal spores before an infection is established, thereby affecting the dynamics of social immunity in the colony.

Keywords: inbreeding, social immunity, hygienic behaviour, grooming, Cardiocondyla ants, Metarhizium fungi

1. Introduction

The susceptibility of individuals to disease is strongly affected by genetic effects. These include the presence of particular alleles at resistance loci (Carius et al. 2001; Lambrechts et al. 2005) and the level of homozygosity within host organisms, i.e. the inbreeding effect (O'Brien & Evermann 1988; Arkush et al. 2002; Whiteman et al. 2006; Luong et al. 2007; but see cases where particular resistant genotypes become fixed (Ouborg et al. 2000; Haag et al. 2003; Spielman et al. 2004)). The underlying genetics can affect two lines of host disease defence: its anti-parasite behaviour and physiological immune system (Arkush et al. 2002; Luong et al. 2007).

(a). Disease susceptibility and levels of defence in social insects

In societies, disease dynamics are not only affected by selection at the individual level, but also the group level. Among others, this is true for insect societies (social bees and wasps, ants and termites) that consist of reproducing queens and multiple generations of their worker offspring. Because social insects live together in close proximity and interact intimately, disease spread between colony members is expected to be facilitated in comparison to solitary individuals (Shykoff & Schmid-Hempel 1991; Schmid-Hempel 1998). To counteract the high risk of disease transmission within colonies, insect societies have evolved cooperative social defences that complement the immune response of individual group members (social immunity; Cremer et al. 2007). Similar to individual defence mechanisms, which include both behavioural (e.g. parasite avoidance and self-grooming) and physiological responses (e.g. the innate immune system and antimicrobial gland secretions), social immunity comprises behavioural and physiological defences that are based on interactions between two or more individuals (Cremer et al. 2007). Examples are allogrooming of exposed nest-mates or brood (Schmid-Hempel 1998), ‘hygienic behaviour’, where workers detect and remove diseased and parasitized brood from the nest (Rothenbuhler & Thompson 1956; Wilson-Rich et al. 2009), and enrichment of the nest material with antimicrobially active substances from the environment (Christe et al. 2003). It has also been shown that social interactions within colonies directly affect the physiological susceptibility of individual group members (Traniello et al. 2002; Ugelvig & Cremer 2007).

(b). Genetic effects on disease resistance in social insects

Similar to individual organisms, colony-level disease susceptibility is influenced by the presence of specific alleles at loci affecting disease resistance. Furthermore, it is affected by the overall genetic diversity of group members. The genetic diversity in colonies has two components: a within-individual (e.g. homozygosity level) and a between-individual (e.g. nest-mate relatedness) component.

In ants and bees, individuals from distinct matri- and patrilines in a single colony can differ in their physiological disease susceptibility (Baer & Schmid-Hempel 2003; Palmer & Oldroyd 2003; Hughes & Boomsma 2004; Reber et al. 2008; Hughes et al. 2010). Individuals may also have different thresholds to perform antiseptic behaviours (Beshers & Fewell 2001; Gramacho & Spivak 2003). A genetic basis of these traits is further corroborated by breeding experiments that allowed creating susceptible versus resistant colonies in honeybees (Rothenbuhler & Thompson 1956; Spivak & Reuter 2001; Swanson et al. 2009). Furthermore, molecular studies combined with quantitative trait analyses have revealed a number of suggestive loci that influence hygienic behaviour (Lapidge et al. 2002; Oxley et al. 2010).

The presence of multiple queens and multiple mating by queens not only creates a larger set of potential resistance alleles being present in the colony, but it also decreases the relatedness between nest-mates. Thereby, between-individual genetic diversity is increased, which in turn reduces disease transmission efficiency. Multiple mating has therefore been suggested as an evolutionary response to parasite pressure (Hamilton 1987; Sherman et al. 1988). Numerous studies on ants and bees have confirmed that colonies with multiple mated queens (Baer & Schmid-Hempel 1999, 2001; Tarpy 2003; Hughes & Boomsma 2004; Tarpy & Seeley 2006; Seeley & Tarpy 2007), as well as multiple as opposed to single queens (Liersch & Schmid-Hempel 1998; Reber et al. 2008), suffer from lower parasite loads.

While multiple mating and multiple queens only affect the between-individual component of genetic diversity, inbreeding simultaneously lowers both within-individual and between-individual diversity. This leads to colonies with high between-nest-mate relatedness and individuals with high levels of homozygosity. Studies of inbreeding in social insects have focused mostly on the within-individual component, and found no negative effect of inbreeding on either the physiological or the behavioural defences of individuals (Gerloff et al. 2003; Calleri et al. 2006). To our knowledge, only a single study on termites has investigated the colony-level effects of inbreeding that result from the interplay of within- and between-individual genetic diversity. Colonies had greater mortality and higher microbial loads after only a single generation of inbreeding, for which the authors suggest potentially lower allogrooming between workers in inbred colonies as a likely mechanism (Calleri et al. 2006).

(c). Anti-pathogen defence in Cardiocondyla ants

To investigate the effects of genetic diversity on individual and social immunity in social Hymenoptera, we compared the disease resistance and antiseptic behaviours of genetically homogeneous and diverse colonies of the ant Cardiocondyla obscurior after exposing brood to the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. We used an experimental set-up that allowed us to test for differences between genetically diverse and homogeneous ant colonies with respect to (i) their susceptibility to the disease (measured as worker survival), (ii) their expression of self- and allogrooming as well as hygienic behaviour (removal of diseased brood from the nest), and (iii) their discrimination ability between pathogenic and non-pathogenic brood treatments.

2. Material and methods

(a). Experimental colonies

Cardiocondyla obscurior colonies were collected from Una, Bahia, Brazil, and reared in the laboratory as described previously (Cremer & Heinze 2003). The social structure of C. obscurior colonies in the field is characterized by highly variable queen numbers, intra-nest mating and the exchange of individuals between nests (Heinze & Delabie 2005; Heinze et al. 2006). We used 16 field colonies to rear two different colony types (eight colonies each) over 4 years, i.e. 8–10 generations. Genetically diverse colonies contained 3–20 queens, the offspring of which were allowed to mate freely with each other and with incoming individuals from other colonies. Genetically homogeneous colonies were obtained by strict brother–sister mating, a single queen per colony and no migration into the nest (Schrempf et al. 2006). We therefore created eight independent inbred lines and eight independent diverse colonies of C. obscurior from our 16 original field colonies.

(b). Simulations of within- and between-individual genetic diversity

To characterize the difference in genetic diversity between the two colony types, we performed simulations revealing that strict inbreeding decreased both the within- and the between-individual genetic diversity of colony members as compared with the diverse colonies (inbreeding coefficient: homogeneous colonies, FIT = 0.87; diverse colonies, FIT = 0.06–0.28; worker–worker relatedness: homogeneous colonies, r = 0.98; diverse colonies, r = 0.16–0.60; for details, see the electronic supplementary material, tables S1, S2 and figure S1).

(c). Experimental set-up and fungal infection of larvae

From each of the 16 colonies, we set up two replicates containing five workers and nine larvae, which were presented in groups of three outside the brood chamber. Before the start of the experiment, larvae were colour-marked by ingestion of different food colours (Schwartau). Larvae in each group were coded with the same colour and received one of three larval treatments. In the live spore treatment, larvae were exposed to 0.3 µl of live conidiospores of the entomopathogenic fungus M. anisopliae var. anisopliae (strain KVL 03–143/Ma 275 dissolved in a 0.05% Triton X-100 solution (Sigma) at a concentration of 109 spores ml−1). In the dead spore treatment, larvae received the same amount and concentration of spores, which, however, had been UV-killed and thus not able to germinate (Ugelvig & Cremer 2007). Larvae in the sham control received a spore-free solution of Triton X-100. Different combinations of colour code and treatment were used in different replicates and colonies, so that the observations occurred blindly with respect to larval treatment (for details, see the electronic supplementary material).

(d). Behavioural observations and larval location

Immediately after the start of the experiment and for the following 4 days, we performed 10 scan samplings per day (each 1–2 s) to record ant worker behaviour. We observed the antiseptic behaviours, worker self-grooming, worker–worker allogrooming and worker–larvae allogrooming, as well as the non-disease-related behaviours, worker running, worker–worker antennation and general brood care (i.e. larval handling and feeding) (for details, see the electronic supplementary material). The frequencies of the observed behaviours were averaged across the two replicates per colony and arcsin square-root-transformed to obtain normal distributions prior to statistical analysis. As the same behaviours were recorded in a time series, we used two-way ANOVAs with repeated measures and post hoc contrasts (JMP 8; for detailed statistical analyses and MANOVA summary tables, see the electronic supplementary material, tables S3–S9).

The location of the larvae was observed every 15 min on day 1 and daily for the following 8 days. Both types of colonies carried most larvae into the brood chamber immediately after the start of the experiment, independent of larval treatment (for details, see the electronic supplementary material). Some of the larvae that had originally been carried into the brood chamber were later removed again and left outside to die. Larval removal data were analysed by Cox proportional regression analysis (SPSS 13; for details on the statistical analyses, see the electronic supplementary material).

(e). Histological analysis of the time course of larval infection

We determined the infection status of the live-spore-treated larvae over the course of the experiment by repeating the experimental set-up and taking out the larvae for histological analysis either 2, 24, 96 or 168 h after spore application (each in eight replicates; for details, see the electronic supplementary material).

(f). Survival and infection status of workers

We recorded the death of workers by Metarhizium infections for 12 days after the start of the experiment and analysed the survival data by the Cox proportional regression analysis (SPSS 13; see the electronic supplementary material for details).

3. Results

(a). Survival and infection status of workers

Of 160 worker ants in the experiment, only a single individual (from a homogeneous colony) died from Metarhizium infection. The risk of workers dying from infection was thus similarly low for workers in the homogeneous and diverse colonies (Cox proportional regression; colony-type effect: Wald statistics = 0.27, d.f. = 1, p = 0.61).

(b). Non-disease-related behaviours

Ants from the diverse colonies spent more time running than workers in the homogeneous colonies (repeated-measures ANOVA, between-subject effect of colony type: F1,14 = 9.14, p = 0.009). The two colony types did not show significant differences in either antennation frequency (F1,14 = 2.821, p = 0.12) or general brood care activity (F5,42 = 0.96, p = 0.45; for details, see the electronic supplementary material, tables S3, S4 and S7).

(c). Grooming behaviour

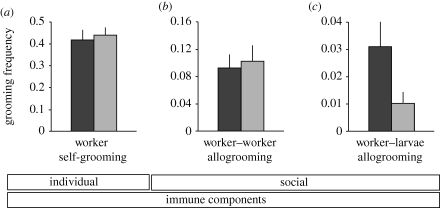

There was no significant difference between the two colony types in worker self-grooming (figure 1a; repeated-measures ANOVA: between-subject effect of colony type: F1,14 = 0.09, p = 0.77) or worker–worker allogrooming (figure 1b; F1,14 = 0.04, p = 0.84).

Figure 1.

Individual and social grooming behaviour. Total grooming frequencies of workers from genetically diverse (dark grey bars) and homogeneous (light grey bars) ant colonies. (a) Worker self-grooming, (b) worker–worker allogrooming, and (c) larval allogrooming performed by adult workers (eight diverse and eight homogeneous colonies, two replicates per colony, mean + s.e.m.). Only worker–larvae allogrooming frequency was significantly lower in homogeneous than in diverse ant colonies.

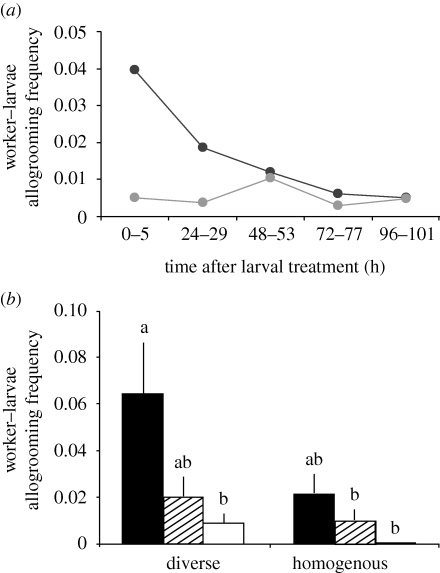

By contrast, worker–larvae allogrooming frequency was significantly higher in the diverse than in the homogeneous colonies (figure 1c; F1,46 = 5.24, p = 0.03). Furthermore, the two colony types differed in their time pattern of larval grooming (as revealed by a significant interaction between colony type and time: F4,43 = 2.70, p = 0.04). In the homogeneous colonies, larval grooming frequency was consistently low throughout the experiment (figure 2a; repeated-measures ANOVA for homogeneous colonies only, within-subject time effect: F4,20 = 0.16, p = 0.96), whereas larval grooming frequency was significantly higher in the first 29 h after larval treatment in the diverse colonies (figure 2a; repeated-measures ANOVA for diverse colonies only: within-subject time effect: F4,20 = 4.23, p = 0.01; post hoc contrasts of starting point to late (greater than 29 h) time points: always p < 0.01; for details of pairwise comparisons, see the electronic supplementary material, table S8).

Figure 2.

Larval grooming by adult workers over time and in response to larval treatment. (a) Daily worker–larvae allogrooming frequency of workers from genetically diverse (dark grey line) and homogeneous (light grey line) colonies. (b) Total worker–larvae allogrooming frequency by workers from the genetically diverse and homogeneous colonies towards the three larval treatments: live-spore-treated larvae (black bars), dead-spore-treated larvae (hatched bars) and sham-treated larvae (white bars; mean + s.e.m.; significance groups (letters) obtained by all pairwise comparisons of ANOVA post hoc Tukey tests). Workers from diverse colonies intensively groomed live-spore-treated larvae within the first 29 h of the experiment, while larval grooming was consistently low and did not differ between larval treatments in the homogeneous colonies.

Worker–larvae allogrooming frequencies did not only differ across time but also between the three larval treatments for the two colony types (i.e. the six treatment groups; figure 2b; repeated-measures ANOVA, between-subject treatment group effect: F5,42 = 4.00, p = 0.005). Workers from the diverse colonies groomed the live-spore-treated larvae more intensively than the sham-control-treated larvae and the dead-spore-treated larvae at intermediate frequencies. The workers from the genetically homogeneous colonies, however, did not groom the live-spore-treated larvae significantly more often than the control larvae, which may be owing to overall low levels of grooming (figure 2b; post hoc all pairwise Tukey test; p < 0.05 for diverse colonies × live spores versus diverse colonies × sham control/homogeneous colonies × dead spores/homogeneous colonies × sham control; all other pairwise comparisons non-significant). Furthermore, the preferential grooming of live-spore-treated larvae by the workers in the diverse colonies was caused mainly by an intensive early grooming of these larvae (same repeated-measures ANOVA: within-subject time effect: F4,39 = 2.74, p = 0.04), post hoc contrasts of starting point to 48–53 h p = 0.06, and to greater than 53 h always p < 0.01).

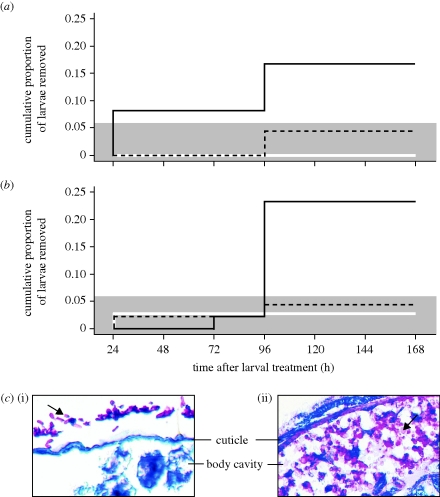

(d). Hygienic behaviour

Both colony types initially carried larvae into the brood chamber and subsequently removed some of them (figure 3; for details, see the electronic supplementary material). The larvae that were removed were almost exclusively live-spore-treated (figure 3a,b; Cox proportional regression; pathogenic–non-pathogenic treatment; diverse colonies: Wald statistics = 7.03, d.f. = 1, p = 0.008; homogeneous colonies: Wald statistics = 7.98, d.f. = 1, p = 0.005). Larvae treated with either dead spores or sham control were removed at low rates, not significantly different from zero for both colony types at any time (Fisher exact test: p > 0.4; for details, see the electronic supplementary material) and not significantly different from each other (Cox proportional regression; dead spores–sham control: Wald statistics = 1.45, d.f. = 1, p = 0.23).

Figure 3.

Larval removal from the brood chamber depending on infection status. Workers from (a) genetically diverse and (b) homogeneous colonies (means of eight colonies each, two replicates per colony) removed live-spore-treated larvae (black solid line) significantly more often than larvae treated with the non-pathogenic dead spores (black dashed line) or sham-treated (white solid line). Removal frequencies of non-pathogenic larvae did not significantly differ from zero in either colony type (as indicated by the grey shading showing the zone of non-significant difference from zero). Only workers from diverse colonies started removal of pathogen-treated larvae within the first 24 h after spore application. (c) Histology of Cardiocondyla larvae (i) within the first 24 h after live spore application (n = 16) and (ii) from 96 h onwards (n = 16; fungus stained pink, ant tissue blue). Fungal spores (i, arrow) did not enter the larval bodies within the first 24 h. From 96 h onwards, substantial hyphal growth (ii, arrow) was detectable inside the body of removed larvae.

Cumulative removal frequencies of pathogen-treated larvae did not differ significantly between the genetically diverse and homogeneous colonies towards the end of the experiment (Fisher's exact test: d.f. = 1; 72 h, p = 0.22; 96 h and following, p = 0.39). Importantly, however, the timing of when colonies started to remove larvae differed between colony types. Only the diverse colonies removed larvae from the brood chamber within the first 24 h after spore application. This early removal of larvae was nearly significantly higher in the diverse than in homogeneous colonies (Fisher's exact test at 24 h, p = 0.07) and was significantly different from zero only in the diverse colonies (p = 0.05). By the time the homogeneous colonies removed the first larvae, the diverse colonies had already taken out 50 per cent of the overall removed larvae (with the remaining 50% to be removed within 96 h; figure 3a,b).

(e). Time pattern of larval infection

Histological analyses revealed that fungal spores had not yet penetrated and infected larvae at either 2 h or 24 h after spore application (figure 3c(i)), while mycelial growth occurred inside the bodies of larvae analysed at 96 h and 168 h after spore treatment (figure 3c(ii)).

4. Discussion

Our study on collective antiseptic and hygienic behaviours in the ant C. obscurior revealed higher allogrooming frequencies and earlier nest removal of pathogen-treated larvae in genetically diverse than in homogeneous colonies. We can thus conclude that inbreeding compromises efficient early anti-pathogen defence in ant societies.

(a). Worker activity and disease susceptibility

Ants from genetically diverse colonies showed higher individual running activity than workers from homogeneous colonies, similar to a higher foraging activity reported in genetically more diverse honeybee colonies (Mattila & Seeley 2007). Apart from that, the frequencies of other non-disease-related behaviours, such as antennation and general brood care behaviour as well as most antiseptic behaviours (see below), did not differ between the ants from the two colony types, indicating that inbreeding did not lower all activities equally.

Both colony types also showed a similarly low risk of workers contracting the disease from the exposed brood, revealing that inbreeding did not make the ants more susceptible to Metarhizium infection. Overall low cross-infection has also been found among nest-mate termite nymphs and leaf-cutter ant workers (Rosengaus et al. 1998; Hughes et al. 2002).

(b). Grooming behaviour

Ants from both colony types performed worker self-grooming and worker–worker allogrooming at the same frequencies (figure 1a,b). Previously, data on termites also revealed no negative effect of inbreeding on self-grooming rates (Calleri et al. 2006). Likewise, allogrooming frequencies were not found to be affected by genetic diversity in leaf-cutting ants (Hughes & Boomsma 2004). Together, these studies show that individual and social antiseptic behaviour does not seem to be compromised in genetically homogeneous insect societies. Given the similar disease resistance levels (survival) and individual and social grooming activities, we can also conclude that the physiological immunity of individual ants was not likely to have been affected by the 8–10 generations of brother–sister matings. The same has been found after one generation of inbreeding in termites and bumble-bees (Gerloff et al. 2003; Calleri et al. 2006).

In contrast to these similarities, workers from homogeneous colonies were compromised in worker–larvae allogrooming, an important component of social immunity (figure 1c). Only ants from diverse colonies showed intensive grooming of live-spore-treated larvae in the first 29 h after the start of the experiment (figure 2a,b). A similar immediate but temporary upregulation in grooming behaviour has been reported in diverse colonies of termites and other ant species after colony exposure to pathogens (Kermarrec et al. 1986; Rosengaus et al. 1998; Jaccoud et al. 1999; Currie & Stuart 2001), but its absence in inbred colonies is an entirely novel finding of this study.

What causes this deficit in expressing early antiseptic behaviour towards the pathogen-treated larvae in ants from genetically homogeneous colonies? At the individual level, an overall higher homozygosity of workers may (i) result in a lower general physical performance, including antiseptic behaviours (comparable to Luong et al. 2007); or (ii) affect the ants' ability to detect and/or trigger a response to the pathogen. Our data indicate that the first explanation is highly unlikely, as workers from genetically homogeneous colonies did not show a lower rate of grooming themselves (figure 1a) or other adult workers (figure 1b). Neither did they show less general brood care.

Instead, it seems likely that homozygosity affects the ability of individual ants to detect or respond to live fungal spores or that differences in between-individual genetic diversity affect colony-level performance. All physiological abilities of individuals being equal, the high relatedness between nest-mates in inbred colonies may reduce the likelihood that the threshold to react to the stimulus ‘spores’ with the action ‘grooming behaviour’ is reached in any group member. Our data are thus also in line with response threshold models for division of labour (Beshers & Fewell 2001).

(c). Hygienic behaviour

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to describe hygienic behaviour in ants (i.e. the detection and removal of diseased brood). So far, the behaviour has only been known for honeybees (Rothenbuhler & Thompson 1956; Wilson-Rich et al. 2009), which raise their brood in individual brood cells. Ant brood, on the other hand, is clumped together in brood piles that can facilitate larval cross-infection (L. V. Ugelvig & S. Cremer 2006, unpublished data). This suggests that hygienic behaviour may be at least equally important in ants as in honeybees. The ants in our experiment excluded larvae from the brood chamber over the duration of a week (figure 3), which covers the time course of a typical Metarhizium infection (Ugelvig & Cremer 2007). The expression of this hygienic behaviour is a direct consequence of our treatment of larvae with fungal spores, as it did not occur in an additional control set-up where colonies had received only fungus-free control larvae (electronic supplementary material).

All colonies only removed the live-spore-treated larvae at frequencies significantly different from zero, but the timing of larval removal differed between the two colony types. Only ants from the diverse colonies started removal of live-spore-treated larvae within the first 24 h after spore application, and histological analyses revealed that fungal spores had not yet penetrated, i.e. infected, these ‘early-removed’ larvae (figure 3c(i)). ‘Late-removed’ larvae, on the other hand, contained mycelial growth inside their bodies (figure 3c(ii)). This confirms the time pattern of Metarhizium infection in other arthropods, where attachment of spores to the host cuticle and its penetration was found to occur after approximately 6 h and 24–48 h, respectively (Vestergaard et al. 1999; Arruda et al. 2005). Thus, ants from both colony types reacted to signs of larval sickness by late larval removal, but only ants from diverse colonies had the additional capacity to perceive and/or react to the presence of the live, pathogenic fungal spores prior to infection. The fact that larvae exposed to dead fungal spores and spore-free controls were treated similarly indicates that the ants detect and respond to cues of the live spores themselves or cues released throughout the germination process, and not the sheer physical presence of non-germinating spores.

These cues are likely to be of a chemical nature, as termites react to volatile compounds released from spores of M. anisopliae in an olfactometer (Mburu et al. 2009), and volatile compounds of another fungal pathogen (Ascosphaera apis; chalkbrood disease) have been shown to elicit hygienic behaviour in honeybees (Swanson et al. 2009). Furthermore, honeybee workers that uncap infected brood cells in their colonies apparently have better chemosensory capacities than bees not performing this task (Masterman et al. 2001; Gramacho & Spivak 2003; Wilson-Rich et al. 2009).

(d). Potential benefits of early antiseptic behaviours

We suggest a twofold prophylactic effect of the intensive early grooming of live-spore-treated larvae (figure 2a) and the early removal of those larvae from the brood chamber (figure 3a). First, quick grooming of fungal spores, before they attach firmly or enter the host cuticle, is most efficient to decrease spore number on the exposed individuals. This reduces the likelihood of individual infection (Rosengaus et al. 1998; Hughes et al. 2002), especially if spore dosage drops below a critical threshold value (this was not likely to be the case in our experiment owing to the high initial exposure dosage). Second, early grooming and in particular early removal will lower the risk of cross-infection of hitherto unexposed larvae in the brood pile. The early anti-pathogen defences observed in the genetically diverse colonies therefore probably affect both individual and colony-level disease dynamics. The failure of workers from homogeneous colonies to perform those early social defences may thus explain the high parasite load observed in inbred field colonies of social insects (Calleri et al. 2006).

(e). Potential basis of impaired antiseptic behaviours

As the reduction of antiseptic behaviours was observed in all eight inbred lines of Cardiocondyla, each originating from a different field colony, we conclude that the described phenomenon is not a result of a specific genotype with low chemical detection ability, but rather is an effect of decreased genetic diversity within colonies or individuals. Currently, we can only speculate that a possible underlying mechanism may originate from either a reduced chemosensory capacity of the inbred adult workers to detect the pathogen, or a weaker ‘groom me' or ‘remove me' signal elicited by the inbred larvae. This may be caused by a different interaction of the fungal spores with the cuticle of inbred versus non-inbred larvae. However, studies on genetically diverse termites and ants (Jaccoud et al. 1999; Mburu et al. 2009) suggest that workers already change their behaviour in the presence of pure dried spores of M. anisopliae without any interaction with the host cuticle, making an impaired pathogen detection capacity of the adult Cardiocondyla ants a more likely explanation.

Alternatively, the discrimination capacities of individual workers from the genetically homogeneous colonies are unaltered but fail to trigger the same response as observed in workers from the genetically diverse colonies. We consider this unlikely as the ants from homogeneous colonies also ultimately remove sick larvae from the nest. Lower pathogen perception abilities of individual ants in response to their homozygosity coupled with a low between-individual diversity in task thresholds (Beshers & Fewell 2001) would be a sufficient mechanism to explain the observed colony-level differences.

Our behavioural approach thus allowed us to bring forward novel and testable hypotheses on the mechanisms underlying the observed delay in anti-pathogen behaviours in genetically uniform ant societies. To disentangle whether the observed phenomena are mainly based on differences in individual homozygosity or on differences in genetic relatedness between group members, future studies should compare colonies differing only in homozygosity or relatedness levels. Given the heritable differences in chemosensory capacities of honeybees (Gramacho & Spivak 2003; Spivak et al. 2003; Swanson et al. 2009), it would be highly valuable to put such future studies into a neuro-immunological framework.

Acknowledgements

Performed experiments comply with the laws of Germany.

We thank M. Stock for help with experiments, C. Wanke, B. Echtenacher and R. Jung for help with histological sections and S. Schneuwly for providing the microscope and camera facilities. We also thank D. Ebert, P. d'Ettorre, F. Roces and M. Sixt for discussion, and S. Tragust, M. Sixt and S. A. O. Armitage for comments on the manuscript. Ant collection was made possible through a permit by the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology (RMX 004/2). Financial support was obtained from the European Commission (Marie Curie Reintegration Grant ERG-036569 to S.C.) and the German Research Foundation (CR 118/2 to S.C., SCHR 1135/1 to A.S. and HE 1623/22 to J.H.).

References

- Arkush K. D., Giese A. R., Mendonca H. L., McBride A. M., Marty G. D., Hedrick P. W.2002Resistance to three pathogens in the endangered winter-run chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha): effects of inbreeding and major histocompatibilty complex genotypes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 59, 966–975 (doi:10.1139/f02-066) [Google Scholar]

- Arruda W., Lübeck I., Schrank A., Vainstein M. H.2005Morphological alterations of Metarhizium anisopliae during penetration of Boophilus microplus ticks. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 37, 231–244 (doi:10.1007/s10493-005-3818-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer B. C., Schmid-Hempel P.1999Experimental variation in polyandry affects parasite loads and fitness in a bumble-bee. Nature 397, 151–154 (doi:10.1038/16451) [Google Scholar]

- Baer B., Schmid-Hempel P.2001Unexpected consequences of polyandry for parasitism and fitness in the bumblebee Bombus terrestris. Evolution 55, 1639–1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer B., Schmid-Hempel P.2003Bumblebee workers from different sire groups vary in susceptibility to parasite infection. Ecol. Lett. 6, 106–110 (doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00411.x) [Google Scholar]

- Beshers S. N., Fewell J. H.2001Models of division of labour in social insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 46, 413–440 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.413) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleri D. V., II, McGrail Reid E., Rosengaus R. B., Vargo E. L., Traniello J. F. A.2006Inbreeding and disease resistance in a social insect: effects of heterozygosity on immunocompetence in the termite Zootermopsis angusticollis. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 2633–2640 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3622) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carius H. J., Little T. J., Ebert D.2001Genetic variation in a host–parasite association: potential for coevolution and frequency-dependent selection. Evolution 55, 1136–1145 (doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christe P., Oppliger A., Bancala F., Castella G., Chapuisat M.2003Evidence for collective medication in ants. Ecol. Lett. 6, 19–22 (doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00395.x) [Google Scholar]

- Cremer S., Heinze J.2003Stress grows wings: environmental induction of winged dispersal males in Cardiocondyla ants. Curr. Biol. 13, 219–223 (doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00012-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer S., Armitage S. A. O., Schmid-Hempel P.2007Social immunity. Curr. Biol. 17, R693–R702 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie C. R., Stuart A. E.2001Weeding and grooming of pathogens in agriculture by ants. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 1033–1039 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1605) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff C. U., Ottmer B. K., Schmid-Hempel P.2003Effects of inbreeding on immune response and body size in a social insect, Bombus terrestris. Funct. Ecol. 17, 582–589 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00769.x) [Google Scholar]

- Gramacho K. P., Spivak M.2003Differences in olfactory sensitivity and behavioural responses among honey bees bred for hygienic behavior. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 54, 472–479 (doi:10.1007/s00265-003-0643-y) [Google Scholar]

- Haag C. R., Sakwinska O., Ebert D.2003Test of synergistic interaction between infection and inbreeding in Daphnia magna. Evolution 57, 777–783 (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00289.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W. D.1987Kinship, recognition, disease and intelligence. In Animal societies: theories and facts (eds Ito Y., Brown J. L., Kikkawa J.), pp. 81–102 Tokyo, Japan: Japan Scientific Societies Press [Google Scholar]

- Heinze J., Delabie J. H. C.2005Population structure of the male-polymorphic ant Cardiocondyla obscurior. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna E 40, 187–190 (doi:10.1080/01650520500175250) [Google Scholar]

- Heinze J., Cremer S., Eckl N., Schrempf A.2006Stealthy invaders: the biology of Cardiocondyla tramp ants. Insect. Soc. 53, 1–7 (doi:10.1007/s00040-005-0847-4) [Google Scholar]

- Hughes W. O. H., Boomsma J. J.2004Genetic diversity and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ant societies. Evolution 58, 1251–1260 (doi:10.1554/03-546) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes W. O. H., Eilenberg J., Boomsma J. J.2002Trade-offs in group living: transmission and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1811–1819 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes W. O. H., Bot A. N. M., Boomsma J. J.2010Caste-specific expression of genetic variation in the size of antibiotic-producing glands of leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 609–615 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1415) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccoud D. B., Hughes W. O. H., Jackson C. W.1999The epizootiology of a Metarhizium infection in mini-nests of the leaf-cutting ant Atta sexdens rubropilosa. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 93, 51–61 (doi:10.1023/A:1003830625680) [Google Scholar]

- Kermarrec A., Febvay G., Decharme M.1986Protection of leaf-cutting ants from biohazards: is there a future for microbiological control? In Fire ants and leaf-cutting ants: biology and management (eds Lofgren C. S., Vander Meer R. K.), pp. 339–356 Boulder, CO: Westview Press [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts L., Halbert J., Durand P., Gouagna L. C., Koella J. C.2005Host genotype by parasite genotype interactions underlying the resistance of anopheline mosquitoes to Plasmodium falciparum. Malar. J. 4, 3 (doi:10.1186/1475-2875-4-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidge K., Oldroyd B. P., Spivak M.2002Seven suggestive quantitative trait loci influence hygienic behavior of honey bees. Naturwissenschaften 89, 565–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liersch S., Schmid-Hempel P.1998Genetic variation within social insect colonies reduces parasite load. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 221–225 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0285) [Google Scholar]

- Luong L. T., Heath B. D., Polak M.2007Host inbreeding increases susceptibility to ectoparasitism. J. Evol. Biol. 20, 79–86 (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01226.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterman R., Ross R., Mesce K. A., Spivak M.2001Olfactory and behavioral response thresholds to odors of diseased brood differ between hygienic and nonhygienic honeybees (Apis mellifera L.). J. Comp. Physiol. 187, 441–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila H. R., Seeley T. D.2007Genetic diversity in honey bee colonies enhances productivity and fitness. Science 317, 362–364 (doi:10.1126/science.1143046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mburu D. M., Ochola L., Maniania N. K., Njagi P., Gitonga L., Ndungu M., Wanjoya A., Hassanali A.2009Relationship between virulence and repellency of entomopathogenic isolates of Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana to the termite Macrotermes michaelseni. J. Insect Physiol. 55, 774–780 (doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.04.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien S. J., Evermann J. F.1988Interactive influence of infectious disease and genetic diversity in natural populations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 3, 254–259 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(88)90058-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouborg N. J., Biere A., Mudde C. L.2000Inbreeding effects on resistance and transmission-related traits in the Silene-Microbotryum pathosystem. Ecology 81, 520–531 [Google Scholar]

- Oxley P., Spivak M., Oldroyd B. P.2010Six quantitative trait loci influence task thresholds for hygienic behaviour in honeybees (Apis mellifera). Mol. Ecol. 19, 1452–1461 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04569.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer K. A., Oldroyd B. P.2003Evidence for intra-colonial genetic variance in resistance to American foulbrood of honey bees (Apis mellifera): further support for the parasite/pathogen hypothesis for the evolution of polyandry. Naturwissenschaften 90, 265–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber A., Castella G., Christe P., Chapuisat M.2008Experimentally increased group diversity improves disease resistance in an ant species. Ecol. Lett. 11, 682–689 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01177.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengaus R. B., Maxmen A. B., Coates L. E., Traniello J. F. A.1998Disease resistance: a benefit of sociality in the dampwood termite Zootermopsis angusticollis (Isoptera: Termopsidae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 44, 125–134 (doi:10.1007/s002650050523) [Google Scholar]

- Rothenbuhler W. C., Thompson V. C.1956Resistance to American foulbrood in honey bees. I. Differential survival of larvae of different genetic lines. J. Econ. Entomol. 49, 470–475 [Google Scholar]

- Schmid-Hempel P.1998Parasites in social insects. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- Schrempf A., Aron S., Heinze J.2006Sex determination and inbreeding depression in an ant with regular sib-mating. Heredity 97, 75–80 (doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800846) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley T. D., Tarpy D. R.2007Queen promiscuity lowers disease within honeybee colonies. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 67–72 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3702) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman P. W., Seeley T. D., Reeve H. K.1988Parasites, pathogens, and polyandry in social Hymenoptera. Am. Nat. 131, 602–610 (doi:10.1086/284809) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shykoff J. A., Schmid-Hempel P.1991Parasites and the advantage of genetic variability within social insect colonies. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 243, 55–58 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1991.0009) [Google Scholar]

- Spielman D., Brook B. W., Briscoe D. A., Frankham R.2004Does inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity decrease disease resistance? Conserv. Genet. 5, 439–448 (doi:10.1023/B:COGE.0000041030.76598.cd) [Google Scholar]

- Spivak M., Reuter G. S.2001Varroa destructor infestation in untreated honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies selected for hygienic behavior. J. Econ. Entomol. 94, 326–331 (doi:10.1603/0022-0493-94.2.326) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivak M., Masterman R., Ross R., Mesce K. A.2003Hygienic behavior in the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) and the modulatory role of octopamine. J. Neurobiol. 55, 341–354 (doi:10.1002/neu.10219) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J., Torto B., Kells S., Mesce K. A., Tumlinson J. H., Spivak M.2009Odorants that induce hygienic behavior in honeybees: identification of volatile compounds in chalkbrood-infected honeybee larvae. J. Chem. Ecol. 35, 1108–1116 (doi:10.1007/s10886-009-9683-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpy D. R.2003Genetic diversity within honeybee colonies prevents severe infections and promotes colony growth. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 99–103 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2199) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpy D. R., Seeley T. D.2006Lower disease infections in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies headed by polyandrous vs monandrous queens. Naturwissenschaften 93, 195–199 (doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0091-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traniello J. F. A., Rosengaus R. B., Savoie K.2002The development of immunity in a social insect: evidence for the group facilitation of disease resistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6838–6842 (doi:10.1073/pnas.102176599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugelvig L. V., Cremer S.2007Social prophylaxis: group interaction promotes collective immunity in ant colonies. Curr. Biol. 17, 1967–1971 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard S., Butt T. M., Bresciani T. A., Gillespie A. T., Eilenberg J.1999Light and electron microscopy studies of the infection of the western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) by the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 73, 25–33 (doi:10.1006/jipa.1998.4802) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman N. K., Matson K. D., Bollmer J. L., Parker P. G.2006Disease ecology in the Galapagos Hawk (Buteo galapagoensis): host genetic diversity, parasite load and natural antibodies. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 797–804 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3396) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Rich N., Spivak M., Fefferman N. H., Starks T. S.2009Genetic, individual, and group facilitation of disease resistance in insect societies. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 54, 405–423 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]