Abstract

Landscape transformation by humans is virtually ubiquitous, with several suggestions being made that the world's biomes should now be classified according to the extent and nature of this transformation. Even those areas that are thought to have a relatively limited human footprint have experienced substantial biodiversity change. This is true of both marine and terrestrial systems of southern Africa, a region of high biodiversity and including several large conservation areas. Global change drivers have had substantial effects across many levels of the biological hierarchy as is demonstrated in this review, which focuses on terrestrial systems. Interactions among drivers, such as between climate change and invasion, and between changing fire regimes and invasion, are complicating attribution of change effects and management thereof. Likewise CO2 fertilization is having a much larger impact on terrestrial systems than perhaps commonly acknowledged. Temporal changes in biodiversity, and the seeming failure of institutional attempts to address them, underline a growing polarization of world views, which is hampering efforts to address urgent conservation needs.

Keywords: landscape change, biological invasions, conservation, fire, shrub encroachment, CO2 enrichment

1. Introduction

Transformation of the structure and functioning of landscapes and ecosystems by humans is extensive. In terrestrial systems, the scale thereof has led to calls for the replacement of the more usually recognized biomes with a set of anthropogenic biomes, which cover more than 75 per cent of ice-free land and include 90 per cent of its net primary productivity (NPP; Ellis & Ramankutty 2008). Although some areas may yet be considered untransformed or wild (Sanderson et al. 2002), human activities have influenced these too. The impacts of anthropogenic climate change are almost ubiquitous (Parmesan 2006; Le Roux & McGeoch 2008; Lantz et al. 2009), or are forecast soon to become so (Deutsch et al. 2008), and very few regions globally are free of non-indigenous species, many of which have transformed the structure and functioning of the systems they have invaded (Mooney & Hobbs 2000; Blackburn et al. 2004; Frenot et al. 2005).

The biodiversity consequences of human impacts have recently been summarized in several large studies and reviews (e.g. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) 2005; Parmesan 2006; Butchart et al. 2010). Notable among their many common messages is the absence of information for numerous areas and the influence that this might have on policy, which, irrespective of whether or not it is agreed by international convention, can only be given effect to by national legislation and rigorous implementation thereof. This information deficit is non-random, and related either directly or indirectly to the development status of the area or country concerned (e.g. McGeoch et al. 2010). At times it may also not be recognized explicitly. For example, in Root et al.'s (2003) review of climate change impacts, of the 143 examples used, less than 15 are from the Southern Hemisphere. While the extent of information is increasing rapidly for some areas (e.g. Hughes 2003; Mac Nally et al. 2009a,b), its absence in many others is concerning for several reasons, of which two are most notable.

First, nationally relevant demonstrations of impacts and their socio-economic consequences are often required to galvanize meaningful national responses (Braschler et al. 2010). Although at first this might appear to be partly a consequence of differences in scientific literacy among officials from various states, the position of small-island states relative to others in the climate change mitigation debate suggests otherwise. Moreover, without locally appropriate information, adaptation and mitigation practices are unlikely to succeed (Collier et al. 2008). While this might seem self-evident, it is typically not translated into science budgets in areas that are facing some of the most significant change, and often at rates faster than the global average. From a continental perspective, Africa is a notable example, having among the fastest rates of climate change, tropical forest removal and human population growth, and the lowest science budget votes on average (Collier et al. 2008; Pellikka et al. 2009).

Second, as Gore (1992, p. 37) succinctly recognized: ‘ … even though we already know more than enough, we must also investigate any significant uncertainty’. Such uncertainty is commonplace. For example, the role of changing climates, relative to human development and changes in disease control interventions, in altering the nature and the extent of vector-borne disease prevalence is widely debated (Rogers & Randolph 2000; Patz et al. 2002; Lafferty 2009; Pascual & Bouma 2009), with the basis in data being very narrow in some instances (see Zhou et al. 2004; Hay et al. 2005; Paaijmans et al. 2009; Pascual et al. 2009). Similarly, although the fundamentals of biochemistry and ecology remain spatially unchanged, how these translate upwards into larger scale patterns of biodiversity variation and likely responses to change is spatially highly variable, often on very large, and sometimes unrecognized scales. Two examples serve to illustrate this point. First, the upper thermal tolerance limits to performance of ectotherms show narrow variation across the planet, especially by comparison with lower limits (Addo-Bediako et al. 2000; Gaston et al. 2009). In addition, environmental maximum temperatures are close to the limits of performance in tropical and sub-tropical ecotherms (Deutsch et al. 2008). Even small temperature increases are likely to cause extinction in these areas (Huey et al. 2009), especially because environmental maxima are spatially invariant across the tropics (Gaston & Chown 1999). Thus, migration is less suitable a response than it might be in temperate areas. Second, across a range of levels in the biological hierarchy, patterns in and processes underlying variation differ fundamentally among the hemispheres. North–south differences in responses to low temperature in insects, thermal tolerance in algae, life history and range size patterns of birds, and spatial variation in biodiversity and its underlying causes have all been documented (Chown et al. 2004; Orme et al. 2006; Fernández et al. 2009). Such variation has important and often unappreciated implications for forecasting and investigating environmental change-related impacts, though at times this might not be recognized (Simmons et al. 2004).

Bearing the importance of spatially explicit information on temporal changes in biodiversity in mind, this review therefore highlights several such changes that are largely the consequence of human activities in the terrestrial systems of southern Africa. The aim is not to be comprehensive, but rather to highlight significant examples of change associated with each of the broadly recognized global environmental change drivers—habitat alteration, exploitation, climate change, biological invasions and pollution (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005). In some cases, information from this region has been instrumental in understanding the form of and mechanisms underlying temporal turnover in biodiversity associated with a particular driver (notably the dynamics and impacts of biological invasions—Richardson et al. 2000; Richardson & van Wilgen 2004; Wilson et al. 2009a). In others, the impacts of these drivers and their interactions with each other, and the influence thereon of conservation management responses remain less well appreciated.

2. Habitat alteration

Although western and central Botswana and the coastal regions of Namibia have been identified as among the last of the wild areas of the planet (Sanderson et al. 2002), much of the rest of southern Africa has been subject to extensive transformation, mostly through conversion to croplands and rangelands, as well as to urban areas (Fairbanks et al. 2000; Ellis & Ramankutty 2008). Habitat conversion for agriculture (including forestry) and urban settlement have had the largest impacts on the landscape and on biodiversity (Scholtz & Chown 1993; Biggs & Scholes 2002; Latimer et al. 2004; Biggs et al. 2008), and are predicted to continue to have substantial impacts into the future. Under the most extreme scenario of land-use change, by 2100 the condition of biodiversity (or its intactness) will have declined from about 90 per cent (in the 1990s) compared with untransformed areas, to 60 per cent, with the most profound changes occurring among amphibians and plants (Biggs et al. 2008). Poorly studied and poorly developed but biodiverse areas, such as Angola, are likely to show most change.

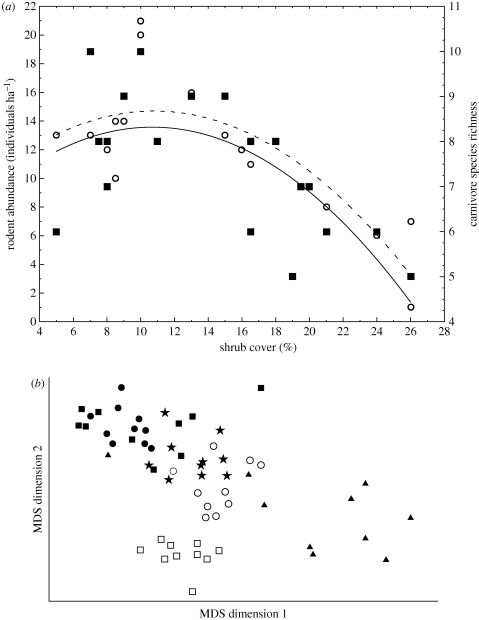

Temporal changes in biodiversity as a consequence of landscape transformation have typically been demonstrated by using space for time substitutions, with comparisons made among relatively untransformed protected areas (though see below) and matched transformed areas, with a few studies encompassing larger extents. These studies generally show substantial differences in richness, abundance and/or diversity among the protected/relatively untransformed areas and adjacent transformed landscapes (Samways & Moore 1991; van der Merwe et al. 1996; Gebeyehu & Samways 2002; Meik et al. 2002; Fabricius et al. 2003; Davis et al. 2004; Witt & Samways 2004; O'Connor 2005; Botes et al. 2006; Blaum et al. 2007a,b, 2009; Krook et al. 2007; Sirami et al. 2009; Wallgren et al. 2009). However, the effects are rarely linear, and often depend on the trophic group and/or habitat preference of the taxon concerned (Krook et al. 2007; Greve et al. submitted), interactions among different biodiversity components (see Keesing 1998; Yarnell et al. 2007; Samways & Grant 2008; Hagenah et al. 2009), or the kinds of human interventions or impacts involved across the areas studied (Fabricius et al. 2003; O'Connor 2005; Botes et al. 2006, figure 1). Nonetheless, substantial changes to biodiversity have taken place in transformed areas by comparison with adjacent untransformed landscapes. At large spatial extents (and a quarter degree grid cell resolution), the efficacy of protected areas is reflected in a richness decline of ca 37 and 21 bird species in high and low NPP areas, respectively, in cells without any conservation by comparison with those completely conserved (Evans et al. 2006a). The latter also often retain large-bodied species, now absent from the former (Greve et al. 2008). These studies demonstrate the value of protected areas in conserving diversity in the region (for general review of protected area efficacy see Gaston et al. 2008). Moreover, such space for time-substitution approaches often serve as the only means for doing so.

Figure 1.

(a) Shrub encroachment effects on the abundance of rodents (open circles, dashed line) and species richness of small carnivores (filled squares, solid line) in the Kalahari Desert. Redrawn from data provided in Blaum et al. (2007a,b). (b) Non-metric multi-dimensional ordination of dung beetle diversity illustrating the difference between two undisturbed habitats (Sand Forest (USF 1998, 2000) and Mixed Woodland (MW 1998, 2000)), and Sand Forest disturbed by elephants (EDSF 2000) and by human utilization (HDSF 1998). Open squares, MW 1998; open circles, MW 2000; filled squares, USF 1998; filled circles, USF 2000; filled triangles, HDSF, 1998; stars, EDSF 2000. Redrawn from Botes et al. (2006).

A variety of investigations of the impacts of human interventions on biodiversity through time have also been conducted in the region. Many involve the documentation and identification of the causes of shrub (or, colloquially, bush) encroachment, and the importance of interactions between ungulate density (or grazing and browsing intensity), fire regimes and rainfall, all of which are considered major drivers of vegetation dynamics (and other aspects of biodiversity dynamics) in the savannas, grasslands and shrublands that dominate the region (O'Connor & Roux 1995; Jeltsch et al. 1997; Roques et al. 2001; Parr et al. 2004; Govender et al. 2006; Owen-Smith & Mills 2006; Higgins et al. 2007; Asner et al. 2009; Hagenah et al. 2009; Staver et al. 2009; Todd & Hoffmann 2009; see also the review by Bond 2008). These studies include some of the longest running tropical ecology experiments (van Wilgen et al. 2003; Bond 2008) and have provided considerable insight into the biodiversity influences of management regimes in conservation areas. At least in savanna areas, they have also shown how different the interactions between rainfall, vegetation structure, ungulates and their predators are in these southern African systems compared with their East African counterparts (Owen-Smith & Mills 2006, 2008; Hopcraft et al. 2010; see also Stock et al. 2010).

Thus, Roques et al. (2001) documented substantial (up to 40% increase), but variable changes in shrub cover across several land-use types over a 50 year period in a Swaziland savanna system. Frequent fires appeared to preclude encroachment (see the fire trap mechanism discussed by Higgins et al. 2007), with an increase in grazing pressure leading to a reduction in fire frequency and shrub encroachment. In the Hluhlwe iMfolozi savanna studied by Bond and co-workers (e.g. Archibald et al. 2005; Krook et al. 2007; Staver et al. 2009; Stock et al. 2010), browsing and fire limit tree density. By determining the spatial distribution of grazers, fire also alters the balance between short grazing lawns and bunch-grasses, favouring the latter and so probably leading to a change in other components of diversity in this dynamic system. In the Kruger National Park savanna, exclusion of herbivores leads to a short-term increase in herbaceous cover in nutrient-rich areas, and a long-term increase in woody vegetation, with downstream effects on other biodiversity components (Asner et al. 2009).

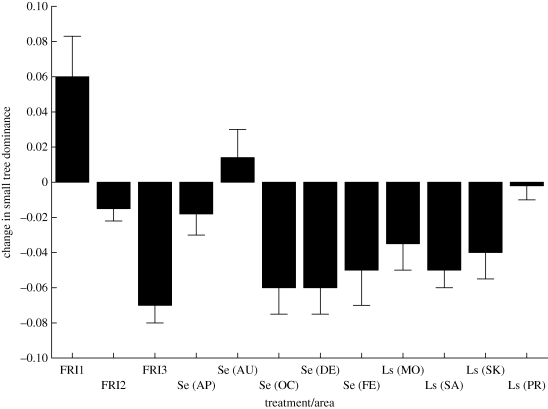

Frequent burning, often justified as a means to provide forage for grazers, may in fact limit the extent of the short-grass habitats preferred by these species (Archibald et al. 2005). Indeed, the impacts of fire regimes on biodiversity and productivity have long occupied land managers in southern Africa (e.g. reviews by van Wilgen 2009a,b). In the Kruger National Park, a series of experimental fire treatments was established in 1954 and has been maintained ever since (van Wilgen et al. 2003). Typically, fire causes a change in tree structural diversity, favouring dominance by small trees, while tree density is not responsive to fire. Changes in fire return interval (or frequency) and season of fire have significant effects on small tree dominance, whereas the former, and landscape type (varying from dry to wet), have an influence on total tree biomass (figure 2). By contrast, ant assemblage structure (richness, abundance and identity) is influenced only by whether a plot has burned or not, and not by the specifics of the burn treatment, although landscape productivity clearly also has effects on richness (Parr et al. 2004; Parr 2008). Management activities thus benefit from these experiments because they provide explicit information on the influence of timing, season and frequency of burns on diversity in landscapes of different productivity.

Figure 2.

The effects of fire return interval (FRI; in years), season (Se; months of the year indicated by letters) and landscape productivity (Ls; from lowest to highest rainfall: MO, Mopani; SA, Satara; SK, Skukuza; PR, Pretoriuskop) on changes in the dominance of small trees following experimental burning regimes over a 40 year period in the Kruger National Park savanna. Redrawn from Higgins et al. (2007).

A final example of the analysis of long-term data on the impacts of habitat transformation illustrates how, within protected areas, management interventions can have substantial, though entirely unintended consequences for species of conservation significance. Between 1986 and 1995, the abundance of Roan antelope and Sable antelope declined precipitously (450 to 45 animals, and 2000 to ca 500 animals, respectively) in the Kruger National Park. The decline was thought to be a consequence predominantly of substantial drought in the Park (Ogutu & Owen-Smith 2003) and this is an important contributing factor. However, further analyses (Harrington et al. 1999; McLoughlin & Owen-Smith 2003; Owen-Smith & Mills 2006) revealed that the provision of water points by managers in the drier, medium–tall grass areas of the park preferred by these species had led to an influx of water-dependent Burchell's Zebra and Blue Wildebeest. The influx in turn precipitated an increase in Lion density, the major predator of large-bodied ungulates in the park (Owen-Smith & Mills 2008). Increasing predation was therefore a key factor, in combination with drought, leading to the decline in Roan and probably also Sable abundance. On this basis, Harrington et al. (1999) called for a review of the policy of augmenting water supplies for wildlife, and in the Kruger National Park substantial changes to the policy have been effected.

3. Exploitation

Terrestrial impacts of exploitation, combined with land-use change, on vertebrates in the region are perhaps best reflected by the substantial differences in the numbers of ungulates seen in the landscapes of the region today by comparison with the 1800s. Arguably one of the clearest documentations of the change comes from the work of C. J. Skead, who converted old accounts of game numbers in the Eastern Cape of South Africa to realistic estimates of abundance (Skead 2007). By comparison with the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the number of large mammals is now much depleted.

Exploitation of vertebrates (and other components of biodiversity) for subsistence continues in many areas across southern Africa (Shackleton & Shackleton 2004; Fusari & Carpaneto 2006; Krook et al. 2007; Hayward 2009), but the emphasis has also changed with the growth of ecotourism and commercial hunting in the region (Van der Waal & Dekker 2000; Reilly et al. 2003; Carruthers 2008). While both activities clearly have conservation benefits, and are often argued in favour of because of these benefits (for discussion see Castley et al. 2001; Van der Merwe & Saayman 2003; Lindsey et al. 2006, 2007), they may also have disadvantages. For example, in the case of Lion, a single hunt may fetch up to US$ 130 000 (Loveridge et al. 2007), and it has been argued, on the basis of analyses and data from East Africa, that as long as males older than 5–6 years old are hunted, population growth can be sustained (Whitman et al. 2004). By contrast, in the Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, males mature later than in East Africa, and even so, more than 30 per cent of the marked males that were killed by hunters were younger than 4 years (Loveridge et al. 2007). The hunting typically also caused territorial turnover, with one home range successively filled four times during the course of the 6 year study. Infanticide associated with territorial turnover was observed, and hunters also shot female lions. Together with increasing hunting off-take, changes in cub sex ratio and other forms of mortality (inadvertent mortality in snares), these practices suggested that the population may well be vulnerable in the region, with all the associated consequences given the role of this large predator in southern African savanna systems (Owen-Smith & Mills 2006, 2008).

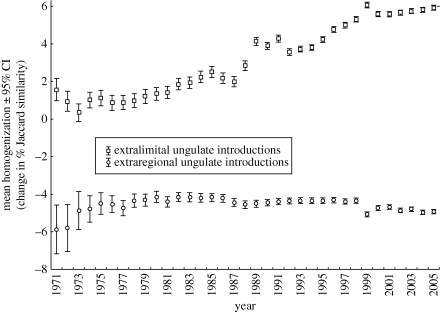

By complete contrast, the enthusiasm for increasing game diversity in particular areas is also having pronounced impacts in the region, largely by causing substantial changes in the ranges of many species. In the case of ungulates, range changes associated with the introduction of species to new areas, largely for ecotourism and hunting purposes, far outweigh any change that might be associated with changing climates in the region (Spear & Chown 2009a). Moreover, the movement of species to new areas is leading to homogenization of the fauna (Spear & Chown 2008). Between the early 1970s and the early 2000s, the ungulate fauna has increased its similarity among quarter-degree grid cells in South Africa by 6 per cent (figure 3). Homogenization has impacts distinct from those typically associated with invasions by single species (see Olden et al. 2004), but nonetheless also indicates the extent to which single species impacts might be concatenated. For example, Bond & Loffell (2001) showed that the introduction of Giraffe, a megaherbivore popular with tourists, to Ithala Game Reserve, an area where it was probably absent historically, is having substantial impacts on three Acacia tree species in the reserve, with one of the species showing complete mortality in those areas accessible to Giraffe. This outcome is in keeping with a global assessment of the consequences of ungulate introductions, where impacts on vegetation are often substantial (Spear & Chown 2009b).

Figure 3.

Temporal trends in homogenization of ungulate assemblages as a consequence of extralimital (i.e. movements within South Africa) and extraregional (importations of new species) introductions to South Africa at the quarter-degree grid cell level between 1971 and 2005. Redrawn from Spear & Chown (2008).

4. Climate change

Terrestrial systems across southern Africa show substantial spatial variation in average annual precipitation and its variability, as well as a quasi-periodic cycle of about 18 years (Tyson & Preston-Whyte 2000). Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, temporal variation in rainfall contributes significantly and often substantially to the population dynamics of a variety of southern African species (O'Connor & Roux 1995; Davis 1996; Little et al. 1996; Dean 1997; Lloyd 1999; Todd et al. 2002; Radford & DuPlessis 2003; Craig et al. 2004; Seely et al. 2005; Owen-Smith & Mills 2006; Thomson et al. 2006; Yarnell et al. 2007; Altwegg & Anderson 2009). Spatial differences in water availability are also significant contributors to correlative models of species distributions, species richness and patterns of vegetation structure, although spatial variation in temperature (typically minima, means and sometimes variability) and landscape heterogeneity are also important (O'Brien 1993; Lloyd & Palmer 1998; Andrews & O'Brien 2000; Erasmus et al. 2002; van Rensburg et al. 2002; Rouget et al. 2004; Richardson et al. 2005; Evans et al. 2006b; Mucina & Rutherford 2006; Thuiller et al. 2006a). Changes in these variables (as well as in composites such as evapotranspiration) therefore should have large influences on species distributions and on species richness in the region, and many forecast-based studies suggest that this is likely to be the case (Erasmus et al. 2002; Hannah et al. 2005; Thuiller et al. 2006b,c; Coetzee et al. 2009, but see also Keith et al. 2008). However, predictions for and realized changes in temperature have been more straightforward to make and document, respectively (e.g. New et al. 2006; Knoesen et al. 2009), than those for rainfall (MacKellar et al. 2007; Knoesen et al. 2009). Thus, what the actual outcome of change will be in many areas is not simple to forecast (e.g. Hoffmann et al. 2009). Sound documentation of temporal changes in terrestrial diversity associated with climate change would therefore appear to be a pressing concern, and extensive records thereof in the literature might, in consequence, be expected.

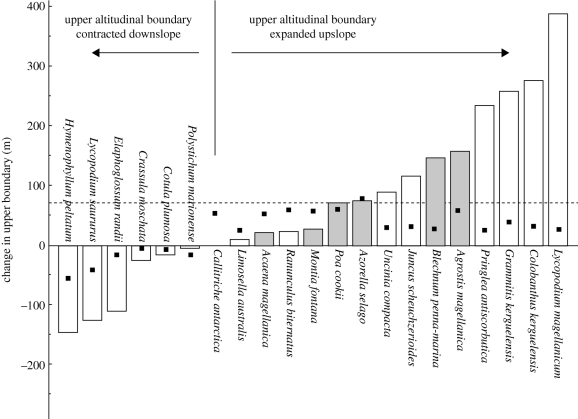

Curiously, information on changes in some component of life history or distribution that is attributable to climate change is uncommon for the region. Perhaps, the most widely known example is the change in demography of the tree aloe, Aloe dichotoma, across its distributional range in western South Africa and in Namibia, which appears to be in keeping with expectations from forecast models for the region (Foden et al. 2007). A comprehensive dataset on changes in altitudinal range over a 40 year period also exists for indigenous vascular plants of the sub-Antarctic Marion Island (which geopolitically forms part of South Africa—see Chown & Froneman 2008). Over the period, an increase in upper elevational limit of 3.4 m yr−1 on average has occurred, with one species showing a 388 m increase (Le Roux & McGeoch 2008; figure 4). Among terrestrial vertebrates, the only range extension currently ascribed to climate change is for the Common Swift (Hockey & Midgley 2009).

Figure 4.

Changes in the upper altitudinal limit of the indigenous vascular flora of sub-Antarctic Marion Island between 1966 and 2006 indicated by the bars (filled bars indicate those species that dominate vascular plant biomass). The points indicate a simulated range boundary change of 10% of the altitudinal range in 1966, whereas the bars show the actual change. Redrawn from le Roux & McGeoch (2008).

Common Swift is one of 18 species that have extended their range to the Cape Peninsula over the past 60 years, but it is the only one for which a combination of increasing afforestation, availability of water (through dams and other irrigation schemes) and urbanization cannot explain the range shift (Hockey & Midgley 2009). Indeed, these authors caution that range shifts in the region should be examined carefully for the extent to which human development factors may be the underlying cause of range shifts, before attributing these to climate change, so echoing similar concerns relating to climate-related changes in vector-borne diseases on the continent (Craig et al. 2004; Lafferty 2009). Claims have also been made for climate change-related range shifts in various invertebrate species (Giliomee 2000), but at least some of these have been the subject of contention (Geertsema 2000).

5. Invasions

Biological invasion by vascular plants is arguably one of the most comprehensively investigated global change drivers for the region, largely because of extensive work undertaken in South Africa. Indeed, the country has a long history of research in the area, which has contributed substantially to the development of the field of invasion biology (MacDonald et al. 1986; Richardson et al. 2000; Rouget & Richardson 2003; van Kleunen et al. 2008; Wilson et al. 2009a). Investigations either using space for time substitutions, or involving time series have shown not only how non-indigenous species have moved from being alien to invasive, but have also documented a wide range of impacts on biodiversity at a range of levels (Richardson & van Wilgen 2004; Gaertner et al. 2009). The focus has not only been on changes to biodiversity as a consequence of species entering the country, but also on traits, vectors and pathways that enable species from South Africa to alter biodiversity in other regions (Thuiller et al. 2005; van Kleunen & Johnson 2007; Lee & Chown 2009).

Although biological invasions by animals have perhaps been less extensively investigated (though e.g. Robinson et al. 2007; Shelton et al. 2008), temporal changes at a number of spatial scales have been explored. Range expansion of the Painted Reed Frog into the Western Cape has also been well documented, and the underlying causes of the expansion shown to be less than straightforward (Tolley et al. 2008). Thus, populations of this species in the far Western Cape are clearly a mixture of three genotypes from areas across the country, and a consequence of human introduction. By contrast, in the eastern part of the Western Cape, it appears that newly documented localities for the species are probably a consequence of range extension from the most westerly part of the range, possibly owing to a shift in rainfall patterns and to the construction of small dams on farmlands. Thus, the range extension includes aspects of direct human movement of the species, indirect facilitation and climate change. Such complex dynamics are forecast to be an increasing feature of future biological invasions across the globe (Walther et al. 2009).

Similarly complex interactions among human activities and invasion seem to be favouring the ongoing transformation of the fynbos biome (a globally significant biodiversity hotspot) by alien pine species, which are also grown commercially as plantation species in the region and elsewhere in the country. Because pines are serotinous, fires stimulate seed release and soil-stored seeds are stimulated to germinate by fire. An increase in fire frequencies in the region (Forsyth & van Wilgen 2008) and an absence of seed-feeding biological control agents (because of industry concerns) suggest that substantial additional transformation of this area by pines, which form dense stands even in the absence of other human disturbance, can be expected (van Wilgen 2009b). If fynbos is to be conserved, in keeping with various conservation strategies for the country, the costs of unplanned fires in the region could amount to an additional US$ 13 million annually (i.e. above the current substantial investment made by local conservation organizations and the national Working for Water programme; van Wilgen 2009b).

6. Pollution

The effects of heavy metal and pesticide pollution and nutrient loading have been the subject of a variety of studies in the region, most notably using longitudinal investigations of freshwater systems or comparable kinds of space for time substitutions, although monitoring of abiotic variables stretches back to the early twentieth century (Davies & Day 1998; Dallas et al. 1999; Dabrowski et al. 2002; de Villiers 2007; de Villiers & Thiart 2007; Reinecke & Reinecke 2007; Chakona et al. 2009; de Villiers & Mkwelo 2009). In many cases, freshwater systems show exceptionally high levels of nutrient (especially P) loading (de Villiers & Thiart 2007). A substantial programme of monitoring of river health in the country has been undertaken at least since the 1990s, including assessments both of abiotic variables and of changes in biota typically using a family-level, invertebrate-based scoring system (the South African scoring system or SASS, Davies & Day 1998; Dallas et al. 1999; Roux 2001). Similar studies have now commenced on other pollutants such as endocrine-disrupting compounds, though these are more recent, with much less temporal extent (e.g. Swart & Pool 2007). In terrestrial systems, the likely significance of nutrient loading, and other forms of pollution from aerial sources, has frequently been noted, but the number of studies of effects on diversity is low (van Tienhoven & Scholes 2004; Wilson et al. 2009b).

Although typically not thought of as a form of pollution, but more a contributor to climate change, alterations in CO2 concentrations (or carbon loading of the atmosphere) may nonetheless be having a profound effect on southern terrestrial systems. While acidification in marine systems is a topic of substantial concern globally (Orr et al. 2005; Hendriks et al. 2010), and the impacts of changes in C : N ratios and stomatal conductance are being widely investigated (Coviella & Trumble 1999; Betts et al. 2007; Piao et al. 2007; Valkama et al. 2007), other potential impacts on terrestrial systems may be less well appreciated. For example, the contribution of increasing CO2 concentrations to ongoing shrub encroachment has been the source of some controversy (Boutton et al. 1994; Archer et al. 1995). Experimental work from the sub-region has demonstrated that increasing CO2 concentrations certainly promote woody plant growth (e.g. Kgope et al. 2010) and a carbon allocation, physiological mechanism generally bears out this expectation (Bond & Midgley 2000). Indeed, changing CO2 concentrations (along perhaps with fire, precipitation changes and the evolution of grazers) probably had a major impact on the past (as far back as the Miocene) extent and spread of grasslands and savanna (Bond et al. 2003; Beerling & Osborne 2006; Kgope et al. 2010). To date, however, it has proven difficult to disentangle the impacts of land-use variation (i.e. extent of grazing and browsing), fire frequency, rainfall variation and CO2 concentration on shrub encroachment. However, a study from the Hluhluwe Imfolozi area (see §2) across three very different land-use types, and using a time series covering the period 1937–2004, has shown that irrespective of land use, shrub/tree encroachment has taken place, and dramatically so (Wigley et al. 2010). Tree cover increased over the period from 14 to 58 per cent in the conservation area, 3 to 50 per cent on a commercial farm and 6 to 25 per cent in a communal grazing area. These areas all have very different grazing pressures and fire regimes, and have shown no systematic trend in rainfall variation. Likewise, although nitrogen deposition may be a driver of the change, the herbaceous component should have been more responsive, leaving the only explanation an increase in CO2 concentration (Wigley et al. 2010). If, as seems likely, the increase in tree cover is a consequence of increasing CO2 concentration, then similar changes can be expected across the subregion, perhaps over-riding human management interventions. The implications are profound not only for biogeochemistry (Kgope et al. 2010) and the shifting balance among indigenous species (see §2), but also because invasive alien woody species are a major agent for biodiversity change across the region (Richardson et al. 2000).

7. Conclusions

Temporal changes in biodiversity in southern African terrestrial systems, as a consequence of direct or indirect human activities, have been both extensive and profound. While the majority appear to be having negative consequences for diversity, this is not always the case. One demonstration thereof is the return of endangered species following clearing of riparian invasive trees (Samways & Sharratt 2010). Moreover, few investigations have been made of how changing climate may reduce the impacts of currently invasive species, or diseases, though obviously this has to be the case in some instances (Bradley et al. 2009; Lafferty 2009). Nonetheless, it is clear that, on balance, human activities are profoundly altering biodiversity in the region, often resulting in a substantial impoverishment thereof. That this should be the case for a region often valued for its biodiversity is perhaps not surprising given global trends (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005), but it is alarming. It also raises the issue, again, of why institutional responses from the national (e.g. Chown et al. 2009) to the international level have typically been so slow and often so unsuccessful (Hamilton 2010). Perhaps increasing urbanization, a burgeoning human population and the associated extinction of experience are partly to blame (Miller 2005). However, wilful denial and increasing tendencies to polarize discussions in an attempt to promote particular worldviews may be another (Gore 2007). In this case, which seems likely to lead to relentless environmental change, it might seem prudent to devote as much of the available resources as possible to conservation action, rather than to further documentation of biodiversity and its change (see Cowling et al. 2010). However, given the success of reasoned argument in improving our livelihoods (Ziman 2007) and the occasional demonstration by our institutions that well-supported evidence can lead to swift changes in policy and its rigorous implementation (Gore 1992), a more balanced approach might be most successful at slowing the change.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Maria Dornelas and Anne Magurran for the invitation to contribute to the Symposium ‘Biological diversity in a changing world’ in celebration of the 350th anniversary of the Royal Society. Melodie McGeoch, Bernard Coetzee, two anonymous reviewers and the editors of this volume provided helpful comments on a previous version of the manuscript. Anel Garthwaite provided assistance with literature searches. This work was partly supported by the Working for Water programme and partly by Stellenbosch University's Overarching Strategic Plan.

Footnotes

One contribution of 16 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Biological diversity in a changing world’.

References

- Addo-Bediako A., Chown S. L., Gaston K. J.2000Thermal tolerance, climatic variability and latitude. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267, 739–745 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1065) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altwegg R., Anderson M. D.2009Rainfall in arid zones: possible effects of climate change on the population ecology of blue cranes. Funct. Ecol. 23, 1014–1021 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01563.x) [Google Scholar]

- Andrews P., O'Brien E. M.2000Climate, vegetation, and predictable gradients in mammal species richness in southern Africa. J. Zool. 251, 205–231 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00605.x) [Google Scholar]

- Archer S., Schimel D. S., Holland E. A.1995Mechanisms of shrubland expansion: land use, climate or CO2? Clim. Change 29, 91–99 (doi:10.1007/BF01091640) [Google Scholar]

- Archibald S., Bond W. J., Stock W. D., Fairbanks D. H. K.2005Shaping the landscape: fire–grazer interactions in an African savanna. Ecol. Appl. 15, 96–109 (doi:10.1890/03-5210) [Google Scholar]

- Asner G. P., Levick S. R., Kennedy-Bowdoin T., Knapp D. E., Emerson R., Jacobson J., Colgan M. S., Martin R. E.2009Large-scale impacts of herbivores on the structural diversity of African savannas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4947–4952 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0810637106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerling D. J., Osborne C. P.2006The origin of the savanna biome. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 2023–2031 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01239.x) [Google Scholar]

- Betts R. A., et al. 2007Projected increase in continental runoff due to plant responses to increasing carbon dioxide. Nature 448, 1037–1041 (doi:10.1038/nature06045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs R., Scholes R. J.2002Land-cover change in South Africa 1911–1993. S. Afr. J. Sci. 98, 420–424 [Google Scholar]

- Biggs R., Simons H., Bakkenes M., Scholes R. J., Eickhout B., van Vuuren D., Alkemade R.2008Scenarios of biodiversity loss in southern Africa in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 18, 296–309 (doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.02.001) [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn T. M., Cassey P., Duncan R. P., Evans K. L., Gaston K. J.2004Avian extinction and mammalian introductions on oceanic islands. Science 305, 1955–1958 (doi:10.1126/science.1101617) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaum N., Rossmanith E., Jeltsch F.2007aLand use affects rodent communities in Kalahari savannah rangelands. Afr. J. Ecol. 45, 189–195 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00696.x) [Google Scholar]

- Blaum N., Rossmanith E., Popp A., Jeltsch F.2007bShrub encroachment affects mammalian carnivore abundance and species richness in semiarid rangelands. Acta Oecol. 31, 86–92 (doi:10.1016/j.actao.2006.10.004) [Google Scholar]

- Blaum N., Seymour C., Rossmanith E., Schwager M., Jeltsch F.2009Changes in arthropod diversity along a land use driven gradient of shrub cover in savanna rangelands: identification of suitable indicators. Biodivers. Conserv. 18, 1187–1199 (doi:10.1007/s10531-008-9498-x) [Google Scholar]

- Bond W. J.2008What limits trees in C-4 grasslands and savannas? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 641–659 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173411) [Google Scholar]

- Bond W. J., Loffell D.2001Introduction of giraffe changes acacia distribution in a South African savanna. Afr. J. Ecol. 39, 286–294 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2028.2001.00319.x) [Google Scholar]

- Bond W. J., Midgley G. F.2000A proposed CO2-controlled mechanism of woody plant invasion in grasslands and savannas. Glob. Change Biol. 6, 865–869 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00365.x) [Google Scholar]

- Bond W. J., Midgley G. F., Woodward F. I.2003The importance of low atmospheric CO2 and fire in promoting the spread of grasslands and savannas. Glob. Change Biol. 9, 973–982 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00577.x) [Google Scholar]

- Botes A., McGeoch M. A., van Rensburg B. J.2006Elephant-and human-induced changes to dung beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) assemblages in the Maputaland Centre of Endemism. Biol. Conserv. 130, 573–583 (doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.01.020) [Google Scholar]

- Boutton T. W., Archer S. W., Nordt L. C.1994Climate, CO2 and plant abundance. Nature 372, 625–626 (doi:10.1038/372625a0) [Google Scholar]

- Bradley B. A., Oppenheimer M., Wilcove D. S.2009Climate change and plant invasions: restoration opportunities ahead? Glob. Change Biol. 15, 1511–1521 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01824.x) [Google Scholar]

- Braschler B., Mahood K., Karenyi N., Gaston K. J., Chown S. L.2010Realizing a synergy between research and education: how participation in ant monitoring helps raise biodiversity awareness in a resource-poor country. J. Insect Conserv. 14, 19–30 (doi:10.1007/s10841-009-9221-6) [Google Scholar]

- Butchart S. H. M., et al. 2010Global biodiversity: indicators of recent declines. Science 328, 1164–1168 (doi:10.1126/science.1187512) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers J.2008‘Wilding the farm or farming the wild?’ The evolution of scientific game ranching in South Africa from the 1960s to the present. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 63, 160–181 [Google Scholar]

- Castley J. G., Boshoff A. F., Kerley G. I. H.2001Compromising South Africa's natural biodiversity—inappropriate herbivore introductions. S. Afr. J. Sci. 97, 344–348 [Google Scholar]

- Chakona A., Phiri C., Chinamaringa T., Muller N.2009Changes in biota along a dry-land river in northwestern Zimbabwe: declines and improvements in river health related to land use. Aquat. Ecol. 43, 1095–1106 (doi:10.1007/s10452-008-9222-7) [Google Scholar]

- Chown S. L., Froneman P. W.(eds)2008The Prince Edward islands. Land–Sea interactions in a changing ecosystem Stellenbosch, South Africa: African Sun Media [Google Scholar]

- Chown S. L., Sinclair B. J., Leinaas H. P., Gaston K. J.2004Hemispheric asymmetries in biodiversity—a serious matter for ecology. PLoS Biol. 2, 1701–1707 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020406) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chown S. L., Spear D., Lee J. E., Shaw J. D.2009Animal introductions to southern systems: lessons for ecology and for policy. Afr. Zool. 44, 248–262 (doi:10.3377/004.044.0213) [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee B. W. T., Robertson M. P., Erasmus B. F. N., van Rensburg B. J., Thuiller W.2009Ensemble models predict Important Bird Areas in southern Africa will become less effective for conserving endemic birds under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 18, 701–710 (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00485.x) [Google Scholar]

- Collier P., Conway G., Venables T.2008Climate change and Africa. Oxford Rev. Econ. Policy 24, 337–353 (doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn019) [Google Scholar]

- Coviella C. E., Trumble J. T.1999Effects of elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide on insect–plant interactions. Conserv. Biol. 13, 700–712 (doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98267.x) [Google Scholar]

- Cowling R. M., Knight A. T., Privett S. D., Sharma G.2010Invest in opportunity, not inventory of hotspots. Conserv. Biol. 24, 633–635 (doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01342.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig M. H., Kleinschmidt I., Nawn J. B., Le Sueur D., Sharp B. L.2004Exploring 30 years of malaria case data in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Part I. The impact of climatic factors. Trop. Med. Int. Health 9, 1247–1257 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01340.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski J. M., Peall S. K. C., Van Niekerk A., Reinecke A. J., Day J. A., Schulz R.2002Predicting runoff-induced pesticide input in agricultural sub-catchment surface waters: linking catchment variables and contamination. Water Res. 36, 4975–4984 (doi:10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00234-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas H. F., Janssens M. P., Day J. A.1999An aquatic macroinvertebrate and chemical database for riverine ecosystems. Water SA 25, 1–8 [Google Scholar]

- Davies B., Day J.1998Vanishing waters. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town Press [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. L. V.1996Seasonal dung beetle activity and dung dispersal in selected South African habitats: implications for pasture improvement in Australia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 58, 157–169 (doi:10.1016/0167-8809(96)01030-4) [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. L. V., Scholtz C. H., Dooley P. W., Bharm N., Kryger U.2004Scarabaeine dung beetles as indicators of biodiversity, habitat transformation and pest control chemicals in agro-ecosystems. S. Afr. J. Sci. 100, 415–424 [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers S.2007The deteriorating nutrient status of the Berg River, South Africa. Water SA 33, 659–664 [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers S., Mkwelo S. T.2009Has monitoring failed the Olifants River, Mpumalanga? Water SA 35, 671–676 [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers S., Thiart C.2007The nutrient status of South African rivers: concentrations, trends and fluxes from the 1970s to 2005. S. Afr. J. Sci. 103, 343–349 [Google Scholar]

- Dean W. R. J.1997The distribution and biology of nomadic birds in the Karoo, South Africa. J. Biogeogr. 24, 769–779 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1997.00163.x) [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch C. A., Tewksbury J. J., Huey R. B., Sheldon K. S., Ghalambor C. K., Haak D. C., Martin P. R.2008Impacts of climate warming on terrestrial ectotherms across latitude. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6668–6672 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0709472105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis E. C., Ramankutty N.2008Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6, 439–447 (doi:10.1890/070062) [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus B. F. N., van Jaarsveld A. S., Chown S. L., Kshatriya M., Wessels K. J.2002Vulnerability of South African animal taxa to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 8, 679–693 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00502.x) [Google Scholar]

- Evans K. L., Rodrigues A. S. L., Chown S. L., Gaston K. J.2006aProtected areas and regional avian species richness in South Africa. Biol. Lett. 2, 184–188 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0435) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K. L., van Rensburg B. J., Gaston K. J., Chown S. L.2006bPeople, species richness and human population growth. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 15, 625–636 (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00253.x) [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius C., Burger M., Hockey P. A. R.2003Comparing biodiversity between protected areas and adjacent rangeland in xeric succulent thicket, South Africa: arthropods and reptiles. J. Appl. Ecol. 40, 392–403 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00793.x) [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks D. H. K., Thompson M. K., Vink D. E., Newby T. S., van den Berg H. M., Everard D. A.2000The South African land-cover characteristics database: a synopsis of the landscape. S. Afr. J. Sci. 96, 69–82 [Google Scholar]

- Fernández M., Astorga A., Navarette S. A., Valdovinos C., Marquet P. A.2009Deconstructing latitudinal species richness patterns in the ocean: does larval development hold the clue? Ecol. Lett. 12, 601–611 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01315.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foden W., et al. 2007A changing climate is eroding the geographical range of the Namib Desert tree Aloe through population declines and dispersal lags. Divers. Distrib. 13, 645–653 (doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00391.x) [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth G. G., van Wilgen B. W.2008The recent fire history of the Table Mountain National Park and implications for fire management. Koedoe 50, 3–9 [Google Scholar]

- Frenot Y., Chown S. L., Whinam J., Selkirk P. M., Convey P., Skotnicki M., Bergstrom D. M.2005Biological invasions in the Antarctic: extent, impacts and implications. Biol. Rev. 80, 45–72 (doi:10.1017/S1464793104006542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusari A., Carpaneto G. M.2006Subsistence hunting and conservation issues in the game reserve of Gile, Mozambique. Biodivers. Conserv. 15, 2477–2495 [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner M., Den Breeyen A., Hui C., Richardson D. M.2009Impacts of alien plant invasions on species richness in Mediterranean-type ecosystems: a meta-analysis. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 33, 319–338 (doi:10.1177/0309133309341607) [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K. J., Chown S. L.1999Why Rapoport's rule does not generalise. Oikos 84, 309–312 (doi:10.2307/3546727) [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K. J., Jackson S. F., Cantu-Salazar L., Cruz-Piñón G.2008The ecological performance of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 93–113 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173529) [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K. J., et al. 2009Macrophysiology: a conceptual re-unification. Am. Nat. 174, 595–612 (doi:10.1086/605982) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebeyehu S., Samways M. J.2002Grasshopper assemblage response to a restored national park (Mountain Zebra National Park, South Africa). Biodivers. Conserv. 11, 283–304 [Google Scholar]

- Geertsema H.2000Range expansion, distribution records and abundance of some Western Cape insects. S. Afr. J. Sci. 96, 396–398 [Google Scholar]

- Giliomee J. H.2000Native insects expanding their ranges and becoming more abundant. S. Afr. J. Sci. 96, 474 [Google Scholar]

- Gore A.1992Earth in the balance. London, UK: Earthscan [Google Scholar]

- Gore A.2007The assault on reason. New York, NY: Penguin Press [Google Scholar]

- Govender N., Trollope W. S. W., van Wilgen B. W.2006The effect of fire season, fire frequency, rainfall and management on fire intensity in savanna vegetation in South Africa. J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 748–758 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01184.x) [Google Scholar]

- Greve M., Gaston K. J., van Rensburg B. J., Chown S. L.2008Environmental factors, regional body size distributions, and spatial variation in body size of local avian assemblages. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 17, 514–523 (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2008.00388.x) [Google Scholar]

- Greve M., Chown S. L., van Rensburg B. J., Dallimer M., Gaston K. J.Submitted The ecological performance of protected areas: a case study for South African birds. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenah N., Prins H. H. T., Olff H.2009Effects of large herbivores on murid rodents in a South African savanna. J. Trop. Ecol. 25, 483–492 (doi:10.1017/S0266467409990046) [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton C.2010Requiem for a species. Why we resist the truth about climate change. London, UK: Earthscan [Google Scholar]

- Hannah L., Midgley G., Hughes G., Bomhard B.2005The view from the Cape. Extinction risk, protected areas, and climate change. BioScience 55, 231–242 (doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0231:TVFTCE]2.0.CO;2) [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R., Owen-Smith N., Viljoen P. C., Biggs H. C., Mason D. R., Funston P.1999Establishing the causes of the roan antelope decline in the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Biol. Conserv. 90, 69–78 (doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00120-7) [Google Scholar]

- Hay S. I., Shanks G. D., Stern D. I., Snow R. W., Randolph S. E., Rogers D. J.2005Climate variability and malaria epidemics in the highlands of East Africa. Trends Parasitol. 21, 52–53 (doi:10.1016/j.pt.2004.11.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward M. W.2009Bushmeat hunting in Dwesa and Cwebe Nature Reserves, Eastern Cape, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 39, 70–84 (doi:10.3957/056.039.0108) [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks I. E., Duarte C. M., Alvarez M.2010Vulnerability of marine biodiversity to ocean acidification: a meta-analysis. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 86, 157–164 (doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2009.11.022) [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S. I., et al. 2007Effects of four decades of fire manipulation on woody vegetation structure in savanna. Ecology 88, 1119–1125 (doi:10.1890/06-1664) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockey P. A. R., Midgley G. F.2009Avian range changes and climate change: a cautionary tale from the Cape Peninsula. Ostrich 80, 29–34 [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M. T., Carrick P. J., Gillson L., West A. G.2009Drought, climate change and vegetation response in the succulent karoo, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 105, 54–60 [Google Scholar]

- Hopcraft J. G. C., Olff H., Sinclair A. R. E.2010Herbivores, resources and risks: alternating regulation along primary environmental gradients in savannas. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 119–128 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey R. B., Deutsch C. A., Tewksbury J. J., Vitt L. J., Hertz P. E., Ãlvarez Pérez H. J., Garland T.2009Why tropical forest lizards are vulnerable to climate warming. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 1939–1948 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1957) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes L.2003Climate change and Australia: trends, projections and impacts. Austral Ecol. 28, 423–443 (doi:10.1046/j.1442-9993.2003.01300.x) [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch F., Milton S. J., Dean W. R. J., van Rooyen N.1997Analysing shrub encroachment in the southern Kalahari: a grid-based modelling approach. J. Appl. Ecol. 34, 1497–1508 [Google Scholar]

- Keesing F.1998Impacts of ungulates on the demography and diversity of small mammals in central Kenya. Oecologia 116, 381–389 (doi:10.1007/s004420050601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith D. A., Akçakaya H. R., Thuiller W., Midgley G. F., Pearson R. G., Phillips S. J., Regan H. M., Araújo M. B., Rebelo T. G.2008Predicting extinction risks under climate change: coupling stochastic population models with dynamic bioclimatic habitat models. Biol. Lett. 4, 560–563 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kgope B. S., Bond W. J., Midgley G. F.2010Growth responses of African savanna trees implicate atmospheric [CO2] as a driver of past current changes in savanna tree cover. Austral Ecol. 35, 451–463 (doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2009.02046.x) [Google Scholar]

- Knoesen D., Schulze R., Pringle C., Dickens C., Kunz R.2009Water for the future: impacts of climate change on water resources in the Orange-Senqu River basin. Report to NeWater, a project funded under the Sixth Research Framework of the European Union. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: Institute of Natural Resources [Google Scholar]

- Krook K., Bond W. J., Hockey P. A. R.2007The effect of grassland shifts on the avifauna of a South African savanna. Ostrich 78, 271–279 (doi:10.2989/OSTRICH.2007.78.2.24.104) [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty K. D.2009The ecology of climate change and infectious diseases. Ecology 90, 888–900 (doi:10.1890/08-0079.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz T. C., Kokelj S. V., Gergel S. E., Henry G. H. R.2009Relative impacts of disturbance and temperature: persistent changes in microenvironment and vegetation in retrogressive thaw slumps. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 1664–1675 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01917.x) [Google Scholar]

- Latimer A. M., Silander J. A., Gelfand A. E., Rebelo A. G., Richardson D. M.2004Quantifying threats to biodiversity from invasive alien plants and other factors: a case study from the Cape Floristic Region. S. Afr. J. Sci. 100, 81–86 [Google Scholar]

- le Roux P. C., McGeoch M. A.2008Rapid range expansion and community reorganization in response to warming. Glob. Change Biol. 14, 2950–2960 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01687.x) [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. E., Chown S. L.2009Breaching the dispersal barrier to invasion: quantification and management. Ecol. Appl. 19, 1944–1957 (doi:10.1890/08-2157.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey P. A., Alexander R., Frank L. G., Mathieson A., Romañach S. S.2006Potential of trophy hunting to create incentives for wildlife conservation in Africa where alternative wildlife-based land uses may not be viable. Anim. Conserv. 9, 283–291 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00034.x) [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey P. A., Roulet P. A., Romañach S. S.2007Economic and conservation significance of the trophy hunting industry in sub-Saharan Africa. Biol. Conserv. 134, 455–469 (doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.09.005) [Google Scholar]

- Little R. M., Crowe T. M., Villacastin-Herrero C. A.1996Conservation implications of long-term population trends, environmental correlates and predictive models for Namaqua sandgrouse. Pterocles namaqua. Biol. Conserv. 75, 93–101 (doi:10.1016/0006-3207(95)00031-3) [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd P.1999Rainfall as a breeding stimulus and clutch size determinant in South African arid-zone birds. Ibis 141, 637–643 (doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1999.tb07371.x) [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd P., Palmer A. R.1998Abiotic factors as predictors of distribution of southern African bulbuls. Auk 115, 404–411 [Google Scholar]

- Loveridge A. J., Searle A. W., Murindagomo F., Macdonald D. W.2007The impact of sport-hunting on the population dynamics of an African lion population in a protected area. Biol. Conserv. 134, 548–558 (doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.09.010) [Google Scholar]

- Mac Nally R., Bennett A. F., Thomson J. R., Radford J. Q., Unmack G., Horrocks G., Vesk P. A.2009aCollapse of an avifauna: climate changes appears to exacerbate habitat loss and degradation. Divers. Distrib. 15, 720–730 (doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2009.00578.x) [Google Scholar]

- Mac Nally R., Horrocks G., Lada H., Lake P. S., Thomson J. R., Taylor A. C.2009bDistribution of anuran amphibians in massively altered landscapes in south-eastern Australia: effects of climate change in an aridifying region. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 18, 575–585 (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00469.x) [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald I. A. W., Kruger F. J., Ferrar A. A.1986The ecology and management of biological invasions in southern Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar N. C., Hewitson B. C., Tadross M. A.2007Namaqualand's climate: recent historical changes and future scenarios. J. Arid Environ. 70, 604–614 (doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2006.03.024) [Google Scholar]

- McGeoch M. A., Butchart S. H. M., Spear D., Marais E., Kleynhans E. J., Symes A., Chanson J., Hoffmann M.2010Global indicators of biological invasion: species numbers, biodiversity impacts and policy responses. Divers. Distrib. 16, 95–108 (doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2009.00633.x) [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin C. A., Owen-Smith N.2003Viability of a diminishing roan antelope population: predation is the threat. Anim. Conserv. 6, 231–236 (doi:10.1017/S1367943003003287) [Google Scholar]

- Meik J. M., Jeo R. M., Mendelson J. R., Jenks K. E.2002Effects of bush encroachment on an assemblage of diurnal lizard species in central Namibia. Biol. Conserv. 106, 29–36 (doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00226-9) [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. R.2005Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 430–434 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney H. A., Hobbs R. J.(eds)2000Invasive species in a changing world. Washington, DC: Island Press [Google Scholar]

- Mucina L., Rutherford M. C.(eds)2006The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelitzia 19. Pretoria, South Africa: South African National Biodiversity Institute [Google Scholar]

- New M., et al. 2006Evidence of trends in daily climate extremes over southern and west Africa. J. Geophys. Res. 111, D14102 (doi:10.1029/2005JD006289) [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien E. M.1993Climatic gradients in woody plant species richness: towards an explanation based on an analysis of southern Africa's woody flora. J. Biogeogr. 20, 181–198 (doi:10.2307/2845670) [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor T. G.2005Influence of land use on plant community composition and diversity in Highland Sourveld grassland in the southern Drakensberg, South Africa. J. Appl. Ecol. 42, 975–988 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.01065.x) [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor T. G., Roux P. W.1995Vegetation changes (1949–1971) in a semi-arid, grassy dwarf shrubland in the Karoo, South Africa: influence of rainfall variability and grazing by sheep. J. Appl. Ecol. 32, 612–626 [Google Scholar]

- Ogutu J. O., Owen-Smith N.2003ENSO, rainfall and temperature influences on extreme population declines among African savanna ungulates. Ecol. Lett. 6, 412–419 (doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00447.x) [Google Scholar]

- Olden J. D., Poff N. L., Douglas M. R., Douglas M. E., Fausch K. D.2004Ecological and evolutionary consequences of biotic homogenization. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 18–24 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme C. D. L., et al. 2006Global patterns of geographic range size in birds. PLoS Biol. 4, 1276–1283 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040208) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr J. C., et al. 2005Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437, 681–686 (doi:10.1038/nature04095) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith N., Mills M. G. L.2006Manifold interactive influences on the population dynamics of a multispecies ungulate assemblage. Ecol. Monogr. 76, 73–92 (doi:10.1890/04-1101) [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith N., Mills M. G. L.2008Predator–prey size relationships in an African large-mammal food web. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 173–183 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01314.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaijmans K. P., Read A. F., Thomas M. B.2009Understanding the link between malaria risk and climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13 844–13 849 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0903423106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmesan C.2006Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 637–669 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100) [Google Scholar]

- Parr C. L.2008Dominant ants can control assemblage species richness in a South African savanna. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 1191–1198 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01450.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr C. L., Robertson H. G., Biggs H. C., Chown S. L.2004Response of African savanna ants to long-term fire regimes. J. Appl. Ecol. 41, 630–642 (doi:10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00920.x) [Google Scholar]

- Pascual M., Bouma M. J.2009Do rising temperatures matter? Ecology 90, 906–912 (doi:10.1890/08-0730.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual M., Dobson A. P., Bouma M. J.2009Underestimating malaria risk under variable temperatures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13 645–13 646 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0906909106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patz J. A., Hulme M., Rosenzweig C., Mitchell T. D., Goldberg R. A., Githeko A. K., Lele S., McMichael A. J., Le Sueur D.2002Climate change (communication arising): regional warming and malaria resurgence. Nature 420, 627–628 (doi:10.1038/420627a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellikka P. K. E., Lötjönen M., Siljander M., Lens L.2009Airborne remote sensing of spatiotemporal change (1955–2004) in indigenous and exotic forest cover in the Taita Hills, Kenya. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 11, 221–232 (doi:10.1016/j.jag.2009.02.002) [Google Scholar]

- Piao S., Friedlingstein P., Ciais P., de Noblet-Ducoudré N. L. D., Zaehle S.2007Changes in climate and land use have a larger direct impact than rising CO2 on global river runoff trends. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15 242–15 247 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0707213104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford A. N., Du Plessis M. A.2003The importance of rainfall to a cavity-nesting species. Ibis 145, 692–694 (doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2003.00198.x) [Google Scholar]

- Reilly B. K., Sutherland E. A., Harley V.2003The nature and extent of wildlife ranching in Gauteng province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 33, 141–144 [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke S. A., Reinecke A. J.2007The impact of organophosphate pesticides in orchards on earthworms in the Western Cape, South Africa. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 66, 244–251 (doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.10.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. M., van Wilgen B. W.2004Invasive alien plants in South Africa: how well do we understand the ecological impacts? S. Afr. J. Sci. 100, 45–52 [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. M., et al. 2000Invasive alien species and global change: a South African perspective. In Invasive species in a changing world (eds Mooney H. A., Hobbs R. J.), pp. 303–349 Washington, DC: Island Press [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. M., Rouget M., Ralston S. J., Cowling R. M., van Rensburg B. J., Thuiller W.2005Species richness of alien plants in South Africa: environmental correlates and the relationship with indigenous plant species richness. Ecoscience 12, 391–402 (doi:10.2980/i1195-6860-12-3-391.1) [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T. B., Govender A., Griffiths C. L., Branch G. M.2007Experimental harvesting of Mytilus galloprovincialis: can an alien mussel support a small-scale fishery? Fisheries Res. 88, 33–41 (doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2007.07.005) [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D. J., Randolph S. E.2000The global spread of malaria in a future, warmer world. Science 289, 1763–1766 (doi:10.1126/science.289.5485.1763) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root T. L., Price J. T., Hall K. R., Schneider S. H., Rosenzweig C., Pounds J. A.2003Fingerprints of global warming on wild animals and plants. Nature 421, 57–60 (doi:10.1038/nature01333) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roques K. G., O'Connor T. G., Watkinson A. R.2001Dynamics of shrub encroachment in an African savanna: relative influences of fire, herbivory, rainfall and density dependence. J. Appl. Ecol. 38, 268–280 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00567.x) [Google Scholar]

- Rouget M., Richardson D. M.2003Inferring process from pattern in plant invasions: a semi-mechanistic model incorporating propagule pressure and environmental factors. Am. Nat. 162, 713–724 (doi:10.1086/379204) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouget M., Richardson D. M., Nel J. L., Le Maitre D. C., Egoh B., Mgidi T.2004Mapping the potential ranges of major plant invaders in South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland using climatic suitability. Divers. Distrib. 10, 475–484 (doi:10.1111/j.1366-9516.2004.00118.x) [Google Scholar]

- Roux D. J.2001Strategies used to guide the design and implementation of a national river monitoring programme in South Africa. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 69, 131–158 (doi:10.1023/A:1010793505708) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samways M. J., Grant P. B. C.2008Elephant impact on dragonflies. J. Insect Conserv. 12, 493–498 (doi:10.1007/s10841-007-9089-2) [Google Scholar]

- Samways M. J., Moore S. D.1991Influence of exotic conifer patches on grasshopper (Orthoptera) assemblages in a grassland matrix at a recreational resort, Natal, South Africa. Biol. Conserv. 57, 117–137 (doi:10.1016/0006-3207(91)90134-U) [Google Scholar]

- Samways M. J., Sharratt N. J.2010Recovery of endemic dragonflies after removal of invasive alien trees. Conserv. Biol. 24, 267–277 (doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01427.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson E. W., Jaiteh M., Levy M. A., Redford K. A., Wannebo A. V., Woolmer G.2002The human footprint and the last of the wild. BioScience 52, 891–904 (doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0891:THFATL]2.0.CO;2) [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz C. H., Chown S. L.1993Insect conservation and extensive agriculture: the savanna of southern Africa. In Perspectives on insect conservation (eds Gaston K. J., New T. R., Samways M. J.), pp. 75–95 Andover, UK: Intercept [Google Scholar]

- Seely M., Henschel J. R., Hamilton W. J., III2005Long-term data show behavioural fog collection adaptations determine Namib Desert beetle abundance. S. Afr. J. Sci. 101, 570–572 [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton C., Shackleton S.2004The importance of non-timber forest products in rural livelihood security and as safety nets: a review of evidence from South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 100, 658–664 [Google Scholar]

- Shelton J. M., Day J. A., Griffiths C. L.2008Influence of largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides, on abundance and habitat selection of Cape galaxias, Galaxias zebratus, in a mountain stream in the Cape Floristic Region, South Africa. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 33, 201–210 (doi:10.2989/AJAS.2008.33.3.2.614) [Google Scholar]

- Simmons R. E., Barnard P., Dean W. R. J., Midgley G. F., Thuiller W., Hughes G.2004Climate change and birds: perspectives and prospects from southern Africa. Ostrich 75, 295–308 [Google Scholar]

- Sirami C., Seymour C., Midgley G., Barnard P.2009The impact of shrub encroachment on savanna bird diversity from local to regional scale. Divers. Distrib. 15, 948–957 (doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2009.00612.x) [Google Scholar]

- Skead C. J.2007Historical incidence of the larger land mammals in the broader eastern cape (eds Boshoff A. F., Kerley G. I. H., Lloyd P. H.), 2nd edn.Port Elizabeth, South Africa: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Bukani Print [Google Scholar]

- Spear D., Chown S. L.2008Taxonomic homogenization in ungulates: patterns and mechanisms at local and global scales. J. Biogeogr. 35, 1962–1975 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01926.x) [Google Scholar]

- Spear D., Chown S. L.2009aThe extent and impacts of ungulate translocations: South Africa in a global context. Biol. Conserv. 142, 353–363 (doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.10.031) [Google Scholar]

- Spear D., Chown S. L.2009bNon-indigenous ungulates as a threat to biodiversity. J. Zool. 279, 1–17 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00604.x) [Google Scholar]

- Staver A. C., Bond W. J., Stock W. D., van Rensburg S. J., Waldram M. S.2009Browsing and fire interact to suppress tree density in an African savanna. Ecol. Appl. 19, 1909–1919 (doi:10.1890/08-1907.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock W. D., Bond W. J., van de Vijver C.2010Herbivore and nutrient control of lawn and bunch grass distributions in a southern African savanna. Plant Ecol. 206, 15–27 (doi:10.1007/s11258-009-9621-4) [Google Scholar]

- Swart N., Pool E.2007Rapid detection of selected steroid hormones from sewage effluents using an ELISA in the Kuils River water catchment area, South Africa. J. Immunoassy Immunochem. 28, 395–408 (doi:10.1080/15321810701603799) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson M. C., Doblas-Reyes F. J., Mason S. J., Hagedorn R., Connor S. J., Phindela T., Morse A. P., Palmer T. N.2006Malaria early warnings based on seasonal climate forecasts from multi-model ensembles. Nature 439, 576–579 (doi:10.1038/nature04503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W., Richardson D. M., Pyšek P., Midgley G. F., Hughes G. O., Rouget M.2005Niche-based modelling as a tool for predicting the risk of alien plant invasions at a global scale. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 2234–2250 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001018.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W., Midgley G. F., Rouget M., Cowling R. M.2006aPredicting patterns of plant species richness in megadiverse South Africa. Ecography 29, 733–744 (doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2006.04674.x) [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W., Broennimann O., Hughes G. O., Alkemade J. R. M., Midgley G. F., Corsi F.2006bVulnerability of African mammals to anthropogenic climate change under conservative land transformation assumptions. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 424–440 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01115.x) [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W., Midgley G. F., Hughes G. O., Bomhard B., Drew G., Rutherford M. C., Woodward F. I.2006cEndemic species and ecosystem sensitivity to climate change in Namibia. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 759–776 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01140.x) [Google Scholar]

- Todd S. W., Hoffman M. T.2009A fence line in time demonstrates grazing-induced vegetation shifts and dynamics in the semiarid Succulent Karoo. Ecol. Appl. 19, 1897–1908 (doi:10.1890/08-0602.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd M. C., Washington R., Cheke R. A., Kniveton R.2002Brown locust outbreaks and climate variability in southern Africa. J. Appl. Ecol. 39, 31–42 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2002.00691.x) [Google Scholar]

- Tolley K. A., Davies S. J., Chown S. L.2008Deconstructing a controversial local range expansion: conservation biogeography of the Painted Reed Frog (Hyperolius marmoratus) in South Africa. Divers. Distrib. 14, 400–411 (doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00428.x) [Google Scholar]

- Tyson P. D., Preston-Whyte R. A.2000The weather and climate of Southern Africa, 2nd edn.Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Valkama E., Koricheva J., Oksanen E.2007Effects of elevated O3, alone and in combination with elevated CO2, on tree leaf chemistry and insect herbivore performance: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 13, 184–201 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01284.x) [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe P., Saayman M.2003Determining the economic value of game farm tourism. Koedoe 46, 103–112 [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe M., Dippenaar-Schoeman A. S., Scholtz C. H.1996Diversity of ground-living spiders at Ngome State Forest, Kwazulu/Natal: a comparative survey in indigenous forest and pine plantations. Afr. J. Ecol. 34, 342–350 [Google Scholar]

- Van der Waal C., Dekker B.2000Game ranching in the Northern Province of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 30, 151–156 [Google Scholar]

- van Kleunen M., Johnson S. D.2007South African Iridaceae with rapid and profuse seedling emergence are more likely to become naturalized in other regions. J. Ecol. 95, 674–681 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01250.x) [Google Scholar]

- van Kleunen M., Manning J. C., Pasqualetto V., Johnson S. D.2008Phylogenetically independent associations between autonomous self-fertilization and plant invasiveness. Am. Nat. 171, 195–201 (doi:10.1086/525057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rensburg B. J., Chown S. L., Gaston K. J.2002Species richness, environmental correlates, and spatial scale: a test using South African birds. Am. Nat. 159, 566–577 (doi:10.1086/339464) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tienhoven A. M., Scholes M. C.2004Air pollution impacts on vegetation in South Africa. In Air pollution impacts on crops and forests. A global assessment (eds Emberson F., Ashmore M., Murray F.), pp. 237–262 Air Pollution Reviews vol. 4.London, UK: Imperial College Press [Google Scholar]

- van Wilgen B. W.2009aThe evolution of fire and invasive alien plant management practices in fynbos. S. Afr. J. Sci. 105, 335–342 [Google Scholar]

- van Wilgen B. W.2009bThe evolution of fire management practices in savanna protected areas in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 105, 343–349 [Google Scholar]

- van Wilgen B. W., Trollope W. S. W., Biggs H. C., Potgieter A. L. F., Brockett B. H.2003Fire as a driver of ecosystem variability. In The Kruger experience. Ecology and management of savanna heterogeneity (eds Du Toit J. T., Rogers K. H., Biggs H. C.), pp. 149–170 Washington, DC: Island Press [Google Scholar]

- Wallgren M., Skarpe C., Bergström R., Danell K., Bergström A., Jakobsson T., Karlsson K., Strand T.2009Influence of land use on the abundance of wildlife and livestock in the Kalahari, Botswana. J. Arid Environ. 73, 314–321 (doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.09.019) [Google Scholar]

- Walther G.-R., et al. 2009Alien species in a warmer world: risks and opportunities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 686–693 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman K., Starfield A. M., Quadling H. S., Packer C.2004Sustainable trophy hunting of African lions. Nature 428, 175–178 (doi:10.1038/nature02395) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigley B. J., Bond W. J., Hoffman M. T.2010Thicket expansion in a South African savanna under divergent land use: local vs. global drivers? Glob. Change Biol. 16, 964–976 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02030.x) [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. R. U., Dormontt E. E., Prentis P. J., Lowe A. J., Richardson D. M.2009aSomething in the way you move: dispersal pathways affect invasion success. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 136–144 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D., Stock W. D., Hedderson T.2009bHistorical nitrogen content of bryophyte tissue as an indicator of increased nitrogen deposition in the Cape Metropolitan Area, South Africa. Environ. Pollut. 157, 938–945 (doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2008.10.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt A. B. R., Samways M. J.2004Influence of agricultural land transformation and pest management practices on the arthropod diversity of a biodiversity hotspot, the Cape Floristic Region, South Africa. Afr. Entomol. 12, 89–95 [Google Scholar]

- Yarnell R. W., Scott D. M., Chimimba C. T., Metcalfe D. J.2007Untangling the roles of fire, grazing and rainfall on small mammal communities in grassland ecosystems. Oecologia 154, 387–402 (doi:10.1007/s00442-007-0841-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Minakawa N., Githeko A. K., Yan G.2004Association between climate variability and malaria epidemics in the East African highlands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2375–2380 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0308714100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziman J.2007Science in civil society. Exeter, UK: Imprint-Academic [Google Scholar]