Abstract

Sphingolipid metabolites are generated throughout the intestinal tract after hydrolysis of orally administered complex sphingolipids and significantly suppress colon cancer in carcinogen-treated CF1 mice. In the present study, the mechanisms of tumor suppression by dietary sphingolipids were investigated. Changes in select genes that are critical in early stages of colon cancer were analyzed in the colonic mucosa of dimethylhydrazine-treated CF1 mice fed AIN76A diet with or without 0.05% sphingomyelin. Supplementation with sphingomyelin did not significantly alter mRNA levels of most of the selected genes. However, a downregulation of ß-catenin (p=0.007) and increased protein levels of connexin-43 (p=0.017) and Bcl-2 (p=0.033) were observed in sphingomyelin-fed animals. This suggests that sphingolipids may be regulating specific post-transcriptional events to reverse aberrant expression of individual proteins. Since the dysregulation of ß-catenin metabolism and its transcriptional activity in addition to a decreased inter-cellular communication has been causally linked to the development of colon cancer while a low Bcl-2 expression is associated with a worse prognosis in colon cancer, the reversal of these early changes may be important events in the prevention of colon cancer by orally administered sphingolipids, and may provide specific molecular biomarkers for sphingolipid efficacy in vivo.

Keywords: Sphingomyelin, ß-catenin, diet, colon cancer prevention, connexin-43, bcl-2

INTRODUCTION

Carcinogenesis is a complex multi-stage process resulting from gene mutations, deletions, translocations, and silencing which all lead to aberrant or dysfunctional gene expression. Although a single gene alteration may primarily be responsible for a specific cancer (i.e., Rb in retinoblastoma, p53 in Li-Fraumeni syndrome), in many other cancers, several causal genetic alterations have been identified. Many of these changes result in the altered life span of transformed cells, loss of cell cycle and apoptosis control and altered communication, adhesion and/or migration properties. Colon cancer has been postulated to result from a series of multiple and consecutive genetic changes [1]. The propensity of these genetic changes for colon cancer is defined by the order and disease stage in which they occur. Neither RAS nor p53 mutations – both frequently seen in colon tumors- can efficiently drive transformation [2], indicating that in the colon neither acts as the `gatekeeper', defined as a gene that has to be inactivated to disturb tissue homeostasis and allow for net proliferation [3]. In the colonic tissue, this gene has been identified as the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) gene, involved in the regulation of proliferation, migration, differentiation and apoptosis of colonocytes. APC mutations have been found in 40 to 80% of sporadic colon cancer and in almost all cases of familial adenomatous polyposis [4, 5]. They already can be detected in aberrant crypt foci (ACF), which are one of the earliest visible morphological changes in colon carcinogenesis and putative colonic precursors of adenomas and adenocarcinomas in both rodents [6] and humans [7]. The resulting truncated APC gene product causes a dysregulation of ß-catenin, a protein that connects E-cadherin to the cytoskeleton but also has important signaling functions in the Wnt pathway. Other early events in colon cancer progression include changes in proliferation, apoptosis, and cell-cell communication. The reversal of these early changes may prevent or decelerate tumor formation and, thus, represent promising targets for colon cancer prevention efforts.

Sphingolipids metabolites are lipid second messengers that are generated by growth factors, cellular stresses, or cytokines. Sphingolipid-mediated changes in proliferation, differentiation, survival or cell death have been reported in many cell lines, and are specific for the cell type, the sphingolipid species that are generated, their concentration and subcellular localization. Bioactive metabolites are also generated by chemotherapeutic compounds such as taxol, cisplatin and daunorubicin and natural chemopreventive agents (i.e., resveratrol, EGCG, curcumin and ß-sitosterol) (see recent review [8]). Although there are numerous reports on the effects of sphingolipids and sphingolipid metabolites in cancer cells in vitro, fewer studies have been conducted to determine the effects of sphingolipids on cancer cells in vivo. One reason may be their inherent toxicity, rapid turnover and their amphiphilic nature that make an organ-specific delivery problematic. Our previous studies were the first to show that complex sphingolipids administered orally significantly reduced carcinogen-induced ACF [9–12] and colon tumor formation in CF1 mice by up to 80 % [13]. We have also shown the dietary sphingolipids suppressed tumor formation in Min mice, a mouse model for familial adenomatous polyposis which was associated with the regulation of ß-catenin expression and localization [14]. Importantly, although the growth inhibitory/cytotoxic metabolites ceramide and sphingosine are released in the intestinal tract after hydrolysis of the complex sphingolipids [see a recent review 15 and 16], no severe side effects by this route of administration were noted in any of our studies or by other laboratories [9–17]. In the present study we have characterized molecular changes in the colonic epithelium from carcinogen-treated CF1 after long-term exposure to orally administered sphingomyelin to gain insight into the underlying mechanisms of the observed ACF and tumor suppression. Here, we have focused on the specificity of changes in the expression of genes critical in the earliest stages of colon cancer. We investigated first changes in ß-catenin which, following its dysregulation, has been causally correlated to the progression of early stages of colon cancer [2, 6] and is a target of dietary sphingolipids in Min mice [14]. To test the specificity of sphingolipid-mediated regulation of gene expression, we also examined the adhesion and communication proteins E-cadherin and Connexin-43. In contrast to the observed increase of ß-catenin levels in early stages of colon cancer, the loss of the expression of these genes has been reported in early stages of cancer in many organs including the colon [18, 19]. Since orally administered sphingolipids reversed carcinogen-induced changes of cell proliferation and apoptosis rather than induced apoptosis [13], we also determined the effect of sphingomyelin on the expression of a panel of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, and cell cycle regulators that have been shown to be targets of sphingolipids in vitro. Our studies reveal that sphingolipids regulate the expression of proteins closely associated with the earliest steps in colon carcinogenesis in a protein-specific manner which may be critical for the prevention of colon cancer by dietary sphingolipids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue harvest

Female CF1 mice, 5 weeks old from Charles Rivers Laboratories (Portage, MI) were injected i.p. with dimethylhydrazine (DMH) (30mg/kg bodyweight, once per week for 6 weeks). All mice were fed the semi-purified, casein-based AIN 76A diet [see formulation 20], which is essentially sphingolipid-free, throughout the study, but two groups received 0.05 % sphingomyelin supplements (by weight) either before (SM-early) or after tumor initiation (SM-late) to compare the preventive and therapeutic potential of sphingomyelin. The sphingomyelin was purified from a lipid whey extract as described previously [13]. Forty-five weeks after the last DMH injection, all mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation, the colons were excised, and the tumors measured and removed for separate analysis. The reduction of tumor incidence and the reversal of carcinogen-induced changes in proliferation and apoptosis in the sphingolipid-fed groups have been reported elsewhere [13].

Randomly selected colonic tissues without tumors were scraped gently with DNase and RNase-free microscopy slides to harvest the epithelial cell layer that was used for both mRNA analyses by RT-PCR and for Western Blot analyses of protein expression. Other colons were fixed in formalin, embedded into paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm for immunohistochemical analysis.

Semi-quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (sqRT-PCR) assay of colonic mucosa scrapings

Total RNA was isolated from the epithelial cells (20 mg wet weight) using the RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Ten samples per group (control, SM-early, SM-late) were processed individually; however, since there was no statistically significant difference in tumor incidence among the supplemented groups (both treatments with sphingomyelin suppressed tumor incidence by approximately 80%, [13]), the results from both sphingomyelin-fed groups were consolidated for data analysis.

RNA was quantitated with the RiboGreen® quantitation Kit (Molecular Probes). A 2-step procedure was used to amplify mRNA. First, cDNA was synthesized from 1.0 μg total RNA with 1μL Oligo-dT primers using the ImProm II RT system (Promega). For the cDNA amplification, the PCR Master Mix Kit from Qiagen was used. Specific forward and reverse primers (Table 1) were added to the Master mix, heated to 94°C for 5 s, then cycled 40 times in a Gene Amplification PCR system (Applied Biosystems) at 94°C for 15 s melt, 60°C for 30 s annealing, and 68°C for 90 s extension. After 7 min at 68°C, the samples were cooled to 4°C. Duplicate reactions for the generation of cDNA as well as duplicate amplification of cDNA by PCR were routinely performed for the samples. Since we have observed in unrelated studies that changes in actin expression can occur during transformation, we included amplification of actin, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and phosphoglycerol kinase (PGK) mRNA as housekeeping controls. The PCR products were examined after separation by electrophoresis on 0.8 % agarose gels (Biorad) with an EagleEye UV detection system (Stratagen). Bands were densitometrically quantitated using Image J (NIH). Values were normalized for actin, GAPDH and PGK expression.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide Primers for RT-PCR

| Primers | Sequences | Product Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actin | forw | AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC | 138 bp |

| rev | CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT | ||

|

| |||

| GAPDH | forw | TCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC | 168bp |

| rev | GCTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGCA | ||

|

| |||

| PKG | forw | CCTCCGCTTTCATGTAGAGGAAGA | 366bp |

| rev | GTAAAGGCCATTCCACCACCAA | ||

|

| |||

| Bax | forw | ACCAAGAAGCTGAGCGAGTGTC | 367 bp |

| rev | ACAAAGATGGTCACGGTCTGCC | ||

|

| |||

| Bad | forw | AGGACTTATCAGCCGAAGCAG | 738 bp |

| rev | TTTCCTAAGGCCTCGAAAGAC | ||

|

| |||

| Bcl-2 | forw | TGTGGCCCAGATAGGCACCCAG | 370 bp |

| rev | ACTTCGCCGAGATGTCCAGCCAG | ||

|

| |||

| Bcl-XL | forw | GACTGGTTGAGCCCATCTCTA | 754 bp |

| rev | GTGAGTGGACGGTCAGTGTCT | ||

|

| |||

| E-cadherin | forw | ACGTATCAGGGTCAAGTGCC | 376 bp |

| rev | CCTGACCCACACCAAAGTCT | ||

|

| |||

| Connexin-43 | forw | CTGCCTTTCGCTGTAACACT | 399 bp |

| rev | CGCTCAAGCTGAACCCATA | ||

|

| |||

| ß-catenin | forw | TTCGCCTTCACTATGGACTACC | 559 bp |

| rev | TTCGCCTTCACTATGGACTACC | ||

|

| |||

| Cyclin D1 | forw | CTGGCCATGAACTACCTGGA | 500 bp |

| rev | GTCACACTTGATCACTCTGG | ||

|

| |||

| c-myc | forw | CCAGCAGCGACTCTGAGG | 683 bp |

| rev | CCAAGACGTTGTGTGTTC | ||

|

| |||

| PKC ßI | forw | TGTGATGGAGTATGTGAACGGGGG | 640 bp |

| rev | TCGAAGTTGGAGGTGTCTCGCTTG | ||

|

| |||

| PKC-ßII | forw | CATCTGGGATGGGGTGACAACC | 420 bp |

| rev | CGGTCGAAGTTTTCAGCGTTTC | ||

Western Blot analysis

Epithelial cell scrapings were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4 and standard protease inhibitors (Roche) for 30 min on ice. The lysates were homogenized using 25 gauge needles, and cleared by centrifugation at 4°C for 30 min at 3000 g. 15–50 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE using 10 % gels. After transfer to PVDF membranes, the blots were blocked with 0.5% skim milk powder in TTBS, and probed with antibodies directed against ß-catenin (Sigma), PKC-ßI and II, cyclin D1, c-myc, Bax and Bcl-2 (from Santa Cruz), Connexin-43 (BD Biosciences) and E-cadherin (Zymed). ß-actin (Sigma) was used to normalize protein expression. The bands were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Biorad), and visualized using ECL (Amersham). The bands were recorded onto X-ray film, measured densitometrically with Image J (NIH) and corrected for the expression of ß-actin.

Immunohistochemical detection of proteins

The Western Blot results were confirmed by immunohistochemical staining using our standard procedures [14]. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated through graded alcohol. After steaming for antigen retrieval and endogenous peroxidase blocking, the sections were blocked with 0.1% BSA and 0.1% calf serum in PBS, and incubated overnight with the primary antibodies. For ß-catenin, we used the anti-ß-catenin antibody from Santa Cruz. The ABC kit from Zymed followed by DAB treatment was used for visualization of the immunocomplex. The sections were briefly counterstained with hematoxylin (Zymed), dehydrated, cleared in xylene and permanently mounted with Histomount® (Zymed). All images were digitally captured on a Nikon 80i epifluorescence microscope, equipped with DIC, and processed with Adobe Photoshop®.

Statistical analysis

Groups were compared using the unpaired t-test for groups that had values sampled from Gaussian distributions. Unpaired t-test followed by Welch's correction was used when the standard deviations differed significantly among the groups, and non-parametric Mann-Whitney Test was used in groups that did not follow Gaussian distribution. All statistical analyses were performed with Instat 3.0a (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

RESULTS

Orally administered sphingomyelin regulates expression of ß-catenin

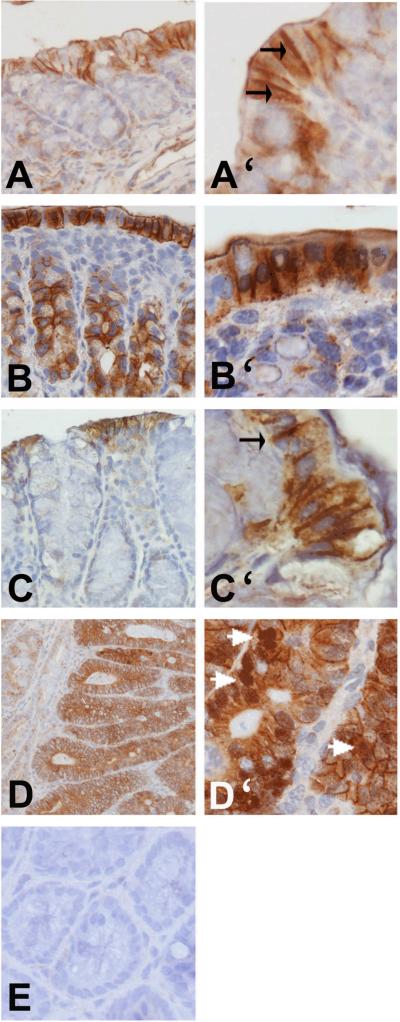

Orally administered sphingolipids regulate ß-catenin expression in an animal model for familial adenomatous polyposis [14]. To establish that ß-catenin dysregulation is also an early event in carcinogen-induced colon cancer and to demonstrate that its regulation by orally administered sphingolipids is not limited to a specific animal model, the effect of the carcinogen treatment and orally administered sphingomyelin on ß-catenin expression and localization was determined by immunohistochemical analysis in the colons of CF1 mice. ß-catenin expression was very weak to moderate in mice not treated with the carcinogen (untreated controls) and was found to be strictly localized at the lateral membranes of cells lining the lumen of the colon (Fig. 1A, A'). ß-catenin expression was elevated after carcinogen treatment (Fig. 1B, B') and, in addition to its localization in membranes, cytosolic stain was detected frequently. The cells of the intestinal lining were generally ß-catenin positive, but moderate to intense ß-catenin expression was also observed in colonic crypt cells. Feeding sphingomyelin to carcinogen-treated mice reduced ß-catenin expression (Fig. 1C, C') and weak to moderate ß-catenin levels were detected mostly in the membranes of cells lining the colonic lumen. Colonic tumors expressed high levels of ß-catenin in the cytosol. Nuclear ß-catenin was only detected in colon tumors (Fig. 1D, D'). This confirms that ß-catenin dysregulation is evident also in carcinogen-treated CF1 mice, that this is an early event and that its regulation by dietary sphingolipids is not limited to a specific animal model.

FIGURE 1.

Changes of ß-catenin expression. ß-catenin was determined by immunohistochemistry in the colon of untreated mice (A, A'), carcinogen-treated mice fed the control diet (B, B') or sphingomyelin supplements (C, C'). Nuclear ß-catenin was only visible in the colon tumors (D, D'). Magnification 20× (A,B, C, D) or 40× (A', B', C', D'). E, antibody specificity control.

Sphingomyelin targets ß-catenin protein levels rather than its transcription

Next, we investigated how sphingolipids regulate ß-catenin levels in vivo. For these studies the colonic epithelium DMH-treated CF1 mice was used. DMH induces permanent transmissible alterations in macroscopically normal appearing colon cells and causes an increase of proliferation and a concomitant decrease in the rate of apoptosis [13, 21], both early events in human colon cancer and suggested driving forces for tumorigenesis. ACF formation could still be detected in the colons forty-five weeks after the last carcinogen injection [13], confirming that processes directing the colonic cells toward transformation and tumor development are constantly ongoing. Thus, the carcinogen-treated colonic mucosa comprises both macroscopically normal but primed cells and cells representing the earliest visible stages in colon carcinogenesis and therefore denotes the appropriate cell population for mechanistic prevention studies.

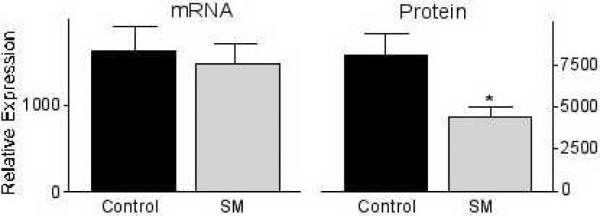

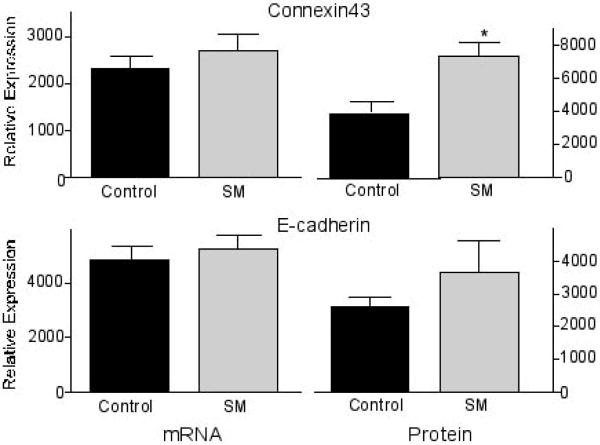

First, the mRNA expression levels of ß-catenin in the colonic mucosa of carcinogen-treated CF1 mice were determined to evaluate an effect on ß-catenin transcription. As shown in Fig. 2, there was no difference in ß-catenin mRNA levels in colonic mucosa of mice fed the AIN 76A diet with or without sphingomyelin supplements. Then, ß-catenin protein expression was determined by Western Blot analysis. In contrast to the mRNA levels, ß-catenin protein expression was significantly reduced in the dietary sphingomyelin group (p<0.001) (Fig. 2). These results confirm the immunohistochemical observations (see Fig. 1), and indicate a modulation of post-transcriptional or post-translational events by the sphingolipids resulting in lower protein expression rather than a regulation of ß-catenin transcription. To determine if this is due to the regulation of processes that specifically modulate ß-catenin expression or possibly the result of a general stimulation of protein metabolism/degradation that would result in an unspecific down-regulation of both detrimental and beneficial proteins, the mRNA levels of connexin-43 and E-cadherin were also investigated. Both proteins are down-regulated in early colon cancer, and thought to be critical for tumor development since the restoration of expression can reverse the phenotype of the cells [22–24]. As shown in Figure 3, there was no significant effect of the dietary sphingomyelin on mRNA levels of either protein; this is comparable to what has been seen with ß-catenin mRNA levels. However, in contrast to our results with ß-catenin protein expression, there was an elevation in protein levels of both E-cadherin and connexin-43 after sphingolipid feeding (p=0.017 for connexin-43; the increase in E-cadherin expression did not reach statistical significance) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Sphingolipids down-regulate ß-catenin protein levels. Feeding 0.05% sphingomyelin (SM) for 45 weeks to carcinogen-treated CF1 mice has no effect on ß-catenin mRNA levels in the colonic mucosa as determined by RT-PCR but significantly reduce its protein expression as determine by SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting. *p<0.05

FIGURE 3.

Sphingolipids up-regulate E-cadherin and Connexin-43. Sphingomyelin (SM) supplements in the diet of carcinogen-treated CF1 mice up-regulate connexin-43 and E-cadherin protein levels in the normal macroscopically appearing colonic mucosa (determined by SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting) without affecting their mRNA levels (determined by RT-PCR). * p=0.017

Sphingolipids do not change the expression of targets of ß-catenin-mediated transcription

To determine if the down-regulation of ß-catenin expression affects its transcriptional activity, the expression of ß-catenin target genes Cyclin D1 and c-myc were investigated since both have been shown to play a role in colon cancer. Neither Cyclin D1 nor c-myc mRNA (Table 2) or protein levels (Table 3) were affected by supplementation of the diet with sphingomyelin. However, neither protein could be detected in the colon by immunohistochemistry, and Cyclin D1 was only detectable in the nuclei of both colonic adenomas and adenocarcinomas (data not shown).

Table 2.

Changes in mRNA levels

| mRNA (relative expression, ± SEM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=10) | SM (n=20) | p | |

| Bax | 4566.9±381.8 | 5068.9±354.6 | 0.3869 |

| Bad | 2146.4 ±542.1 | 1725.9±263.9 | 0.436 |

| Bcl-2 | 2488.7 ± 508.2 | 3279.0±386.3 | 0.237 |

| Bcl-XL | 2882.1 ± 795.4 | 2534.4±519.5 | 0.710 |

| Cyclin D1 | 1426.0 ± 445.8 | 993.4± 192.8 | 0.305 |

| c-myc | 1599.5 ±451.0 | 1801.4±0312.37 | 0.714 |

| PKCßI | 152.8 ± 62.5 | 712.9 ± 163.1 | 0.025 |

| PKCßII | 2035.8 ± 242.9 | 3374.9 ± 408.4 | 0.036 |

Table 3.

Changes in protein levels

| Protein (relative expression, ± SEM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=10) | SM (n=20) | p | |

| Bax | 1233.2±249.2 | 1627.6±566.3 | 0.598 |

| Bcl-2 | 146.1± 57.0 | 544.7 ± 124.6 | 0.033 |

| Cyclin D1 | 5686.9±369.5 | 5551.8±368.1 | 0.809 |

| c-myc | 1230.0±267.5 | 1296.4±234.1 | 0.859 |

| PKC-ßI | 3664.5±604.7 | 2767.8±716.4 | 0.394 |

| PKC-ßII | 2466.5±841.8 | 3040.1±621.5 | 0.593 |

Effects of sphingolipids on the expression of select genes involved in regulation of cell proliferation and death

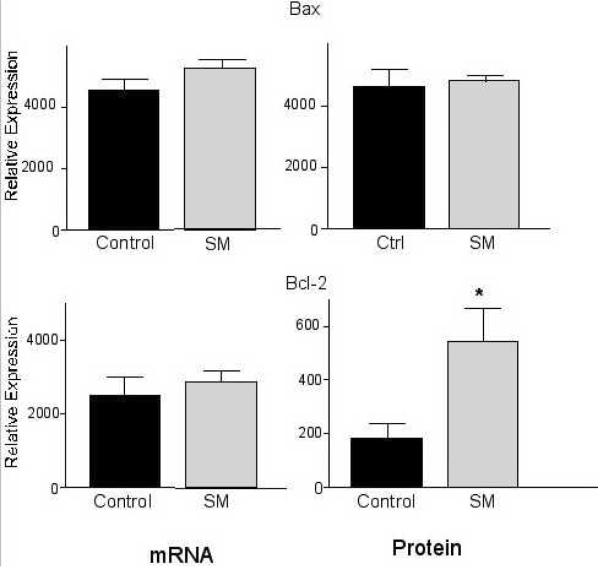

To identify specific signaling pathways that are important for the reversal of carcinogen-induced changes in the rate of proliferation and apoptosis we have reported previously [13], the mRNA levels of select targets known to be regulated by sphingolipid metabolites in vitro were determined in the colonic mucosa. There were no statistically significant effects of sphingomyelin supplements on the mRNA levels of the pro- (Bax, Bad), and anti-apoptotic genes (Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL) selected (Table 2). Since the generation of a pro-apoptotic state could involve changes in the ratio of pro- and anti-apoptotic genes rather than extensive changes in the expression of a single gene, the ratio of Bax plus Bad over Bcl-2 plus Bcl-XL was calculated. However, the difference in the mRNA ratio (1.39 ± 0.15 SEM in the sphingomyelin-fed group versus 1.23 ± 0.17 SEM in the control group) was not statistically significant (p=0.5487).

We then determined if orally administered sphingomyelin can alter protein levels of Bax and Bcl-2 rather than their mRNA levels. As suggested by the mRNA levels, there was no statistically significant change in the bax protein levels (Table 3, Fig. 3). Surprisingly, the protein level of Bcl-2 was significantly elevated in the sphingomyelin-fed mice (p=0.033) (Fig. 3), leading to a significantly lower ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 protein in the treated group (14.75± 3.82 and 4.73±1.73 for control and sphingomyelin-fed, respectively, p=0.023). A cleavage product of approximately 20kDa with pro-apoptotic properties as described by Cheng et al. [25] was not detected.

In addition, putative up-stream regulators of cell growth and death were analyzed. Here protein kinase C (PKC) was chosen because its important role in many facets of cell regulation, and because it is a direct target of sphingolipids [26]; a role of the PKC-ß isozymes in colon cancer has been suggested [27]. In the sphingolipid-fed groups, both PKC-ßI (a splicing variant of PKC-ßII) and PKC-ßII mRNA levels were significantly increased (p=0.025 and p=0.036, respectively) (Table 2, bold). This, however, did not lead to a concurrent increase in either PKC-ßI or PKC-ßII protein levels in the colonic mucosa (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Intestinal cells are constantly exposed to bioactive sphingolipid metabolites when dietary sphingolipids are hydrolyzed in all regions of the intestinal tract to ceramide and sphingosine [16, 27, 28] and regulate cell proliferation and death [10, 11]. These events were associated with the suppression of carcinogen-induced colon cancer in mice [11]. In the present study, expression levels in gene products that may mediate the sphingolipid-induced tumor suppression were evaluated to gain insight into the underlying mechanisms and signaling pathways induced by dietary sphingolipids in the prevention of early stages of colon cancer. Our data indicate that dietary sphingomyelin did not play a role in the regulation of in vivo gene transcription in the colonic mucosa in most of the target genes we had analyzed. In contrast, we found that dietary sphingomyelin selectively influenced the levels of specific proteins that are associated with the earliest stages of colon cancer. Rather than non-specifically altering protein levels independent of the nature or function of the protein, sphingomyelin specifically reversed ß-catenin elevation and decreased connexin-43 protein and E-cadherin levels- changes that are characteristic for early stages of colon carcinogenesis. The reversal of these early events may be critical for the preventive effect of orally administered sphingolipids on colon cancer.

ß-catenin accumulation caused by an APC or, more infrequently, a CTNNB1 mutation is an early event in colon carcinogenesis as indicated by its cytoplasmic accumulation in macroscopically uninvolved colonic mucosa in Min mice [7, 14] or FAP patients [29]. ß-catenin overexpression also appears to be essential for the progression of dysplastic ACF to adenomas [2] while its downregulation reverses the transformed properties of cells [30]. The effect of dysregulated ß-catenin on progression may not only be related to its modulation of cell proliferation [31] but also to its function in cell adhesion and positioning of cells in the colonic crypts. An effect on signaling pathways regulating colonic functions and differentiation has also been suggested [32], emphasizing the importance of ß-catenin during early stages of colon cancer. The down-regulation of ß-catenin by orally administered sphingomyelin by post-transcriptional means demonstrated in the present study confirms our previously reported results in Min mice [14, 33]. The mechanisms of ß-catenin downregulation are currently under investigation in our laboratory. Possible effects of sphingolipids are the increase of protein degradation or reduced stabilization. One target, the ubiquitin-proteasome system, has already been identified as a target for sphingolipids in yeast [34]; however, this was associated with the induction of apoptosis and therefore this pathway may not be relevant here. Another degradation pathway may be the activation of proteases, either directly or indirectly via PKC or other serine/threonine protein kinases and phosphatases that are targets of sphingolipids in vitro. Given the importance of ß-catenin for the progression of the disease, the reversal of aberrant ß-catenin expression may be one important mechanism to prevent colon cancer, and identifies ß-catenin as a promising target for colon cancer prevention with sphingolipids.

ß-catenin that accumulates in the cytosol is translocated to the nucleus where it activates the transcription of genes that are involved in proliferation, adhesion and migration (see www.stanford.edu/~rnusse/wntwindow.html for a list of targets). In the present study, the fixation procedure of the colonic tissue did not allow for a determination of nuclear ß-catenin; instead, we investigated the effect of dietary sphingomyelin on two targets of ß-catenin-mediated transcriptional activity that have been implicated in colon cancer, cyclin D1 and c-myc. Although both c-myc and cyclin D1 can be downregulated by sphingolipid metabolites in vitro [35–37], dietary sphingomyelin did not appear to influence their in vivo expression in the colonic mucosa. This suggests that the elevation of these proteins may not be among the critical early events associated with this model of colon carcinogenesis, and, thus, their down-regulation may not be involved in the suppression of colon cancer by sphingolipids.

Connexins are a family of gap junctional proteins that form aqueous channels for the exchange of small hydrophilic molecules and ions between cells that enable cells to directly communicate and share signaling molecules. The impairment of gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) due to a lack of connexin-43 expression or loss of function is an early event in colon carcinogenesis [19, 24]. The restoration of GJIC has been shown to reverse phenotypical changes in cells and prevent tumor growth [38, 39], and therefore may be an important target in colon cancer prevention. Interestingly, connexin-43 is also a target of Wnt signaling and ß-catenin [40]. In addition to the loss of connexin-43, loss of E-cadherin expression has also been associated with early stages of colon carcinogenesis. Our results indicate a trend towards increased E-cadherin protein levels in the sphingolipid-fed group. E-cadherin is instrumental in regulating intracellular trafficking of connexin-43 [41] and its loss affects connexin-43 expression and localization in cancer cells [43, 43]. Communication and adhesion proteins are especially important in colonic epithelial cells because of the necessity to connect to both underlying matrix and neighboring cells while moving along the crypt axis towards the lumen. Altering these fine-tuned events may cause the retention of transformed cells and support the formation of aberrant crypt foci and subsequently the formation of adenomas and adenocarcinomas.

Sphingolipids targets in vitro are serine/threonine protein kinases and phosphatases that regulate multiple major signaling pathways. Protein kinase C (PKC) was among the first identified targets of sphingolipids [26], and altered expression of PKC isozymes has been reported in various cancers. Of specific interest in this study was PKC-ßII expression that is elevated both during tumor initiation and in colon carcinomas [44, 45] and contributes to increased proliferation of the colonic epithelium [2, 46]. Importantly, although RT-PCR analysis showed an increase of mRNA levels of both enzymes in the sphingolipid-fed mice, this did not correspond to increased protein levels. This confirms earlier results by Gokman-Polar [45]. Unfortunately, in this study, we could not determine whether sphingolipids alter the activity of the enzymes. However, this clearly warrants further investigation because PKC isozymes are also involved in the regulation of ß-catenin metabolism [47].

The increase of Bcl-2 protein expression after feeding sphingolipids is in disagreement with many in vitro observations demonstrating that sphingolipid metabolites lower Bcl-2 and thereby facilitate apoptosis [48]. In vivo, both up- and down-regulated Bcl-2 expression in colon tumors compared to the normal colonic mucosa have been reported [49–50]. Furthermore, Bcl-2 expression has been associated with a better prognosis in colon [51]. Recent studies have demonstrated that an increase in Bcl-2 expression actually increases cell death by compromising the structural integrity of ER and mitochondria, and sensitized cells to apoptosis-inducing agents such as ceramide and staurosporin [52]. At this point it is not clear if this effect of Bcl-2 in both the in vitro and in vivo studies is the result of the cleavage of the protein by Caspase-3 to a bax-like, pro-apoptotic product [25] or the inactivation via dephosphorylation (perhaps of serine 70) by PP2A [53]. The effect of sphingolipid concentrations that do not induce apoptosis - as used in the present study- on both protein size and phosphorylation status will be determined in more detail to uncover its relevance in sphingolipid-mediated colon cancer prevention.

In summary, dietary sphingomyelin specifically prevents or reverses aberrant expression of proteins associated with early stages of colon cancer by modulating post-transcriptional and/or post-translational events. These changes may be critical for the chemopreventive effect of orally administered sphingolipids, and their use of biomarkers for in vivo efficacy of orally administered sphingolipids are currently under investigation.

FIGURE 4.

Up-regulation of Bcl-2 protein levels in the colonic mucosa of sphingolipid-fed CF1 mice. Dietary sphingomyelin (SM) did not affect mRNA levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in the colonic mucosa of carcinogen-treated CF1 mice but increased its protein levels. *p=0.033

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the National Dairy Council and NIH/NCI grant CA109019.

LITERATURE CITED

- [1].Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jen J, Powell SM, Papdopoulos N, Smith KJ, et al. Molecular determinants of dysplasia in colorectal lesions. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5523–55262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cottrell S, Bicknell D, Kaklamanis L, Bodmer WF. Molecular analysis of APC mutations in familial adenomatous polyposis and sporadic colon carcinomas. Lancet. 1992;340:626–630. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92169-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Mutational analysis of the APC/beta-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1130–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Takahashi M, Mutoh M, Kawamori T, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Altered ß-catenin, inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in azoxymethane-induced rat colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1319–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Otori K, Konishi M, Sugiyama K, Hasebe T, et al. Infrequent somatic mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene in aberrant crypt foci of human colon tissue. Cancer. 1998;83:896–900. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980901)83:5<896::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schmelz EM. Sphingolipids and Chemoprevention. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2004;9:2632–2639. doi: 10.2741/1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dillehay DL, Webb SK, Schmelz EM, Merrill AH., Jr. Dietary sphingomyelin inhibits 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer in CF1 mice. J. Nutr. 1994;124:615–620. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schmelz EM, Dillehay DL, Webb S, Reiter A, et al. Sphingomyelin consumption suppresses aberrant colonic crypt foci and increases the proportion of adenomas versus adenocarcinomas in CF1 mice treated with 1,2 dimethylhydrazine: Implications for dietary sphingolipids and colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4936–4941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schmelz EM, Bushnev AB, Dillehay DL, Liotta DC, Merrill AH., Jr. Suppression of aberrant colonic crypt foci by synthetic sphingomyelins with saturated or unsaturated sphingoid base backbones. Nutr. Cancer. 1997;28:81–85. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schmelz EM, Dillehay DL, Sullards MC, Merrill AH., Jr. Colonic cell proliferation and aberrant crypt foci formation are inhibited by dairy glycosphingolipids in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-treated CF1 mice. J. Nutr. 2000;130:522–527. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.3.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lemonnier LA, Dillehay DL, Vespremi MJ, Abrams J, et al. Sphingomyelin in the suppression of colon tumors: Prevention versus intervention. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;419:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schmelz EM, Roberts PC, Kustin EM, Lemonnier LA, et al. Modulation of intracellular ß-catenin localization and intestinal tumorigenesis in vivo and in vitro by sphingolipids. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6723–6729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nilsson A, Duan RD. Absorption and lipoprotein transport of sphingomyelin. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:154–71. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500357-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schmelz EM, Crall KL, LaRocque R, Dillehay DL, Merrill AH., Jr. Uptake and metabolism of sphingolipids in isolated intestinal loops of mice. J. Nutr. 1994;124:702–712. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.5.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nichenametla S, South E, Exon J. Interaction of conjugated linoleic acid, sphingomyelin, and butyrate on formation of colonic aberrant crypt foci and immune functions in rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 2004;67:469–481. doi: 10.1080/15287390490276494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Graff JR, Herman JG, Lapidus RG, Chopra H, et al. E-cadherin expression is silenced by DNA hypermethylation in human breast and prostate carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5195–5199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Husoy T, Olstorn HB, Knutson HK, Loberg EM, et al. Truncated mouse adenomatous polyposis coli reduces connexin32 content and increases matrilysin secretion from Paneth cells. Eur. J. Cancer. 2004;40:1599–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].American Institute of Nutrition Report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc committee on standards for nutritional studies. J. Nutr. 1977;107:1340–1348. doi: 10.1093/jn/107.7.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Weisburger H, Fiala ES. In: Experimental colon carcinogenesis. Autrop H, Williams GM, editors. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1982. pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Efstathiou JA, Liu D, Wheeler JM, Kim HC, et al. Mutated epithelial cadherin is associated with increased tumorigenicity and loss of adhesion and of responsiveness to the motogenic trefoil factor 2 in colon carcinoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:2316–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wheeler J, Kim H, Efstathiou JM, Ilyas M, et al. Hypermethylation of the promoter region of the E-cadherin gene (CDH1) in sporadic and ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancer. Gut. 2008;48:367–371. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Husoy T, Cruciani V, Knutson HK, Mikalsen SO, et al. Cells heterozygous for the ApcMin mutation have decreased gap junctional intercellular communication and connexin43 level, and reduced microtubule polymerization. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:643–650. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen EH, Kirsch DG, Clem RJ, et al. Conversion of Bcl-2 to a Bax-like death effector by caspases. Science. 1997;278:1966–1968. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hannun YA, Loomis CR, Merrill AH, Jr., Bell RM. Sphingosine inhibition of protein kinase C activity and of phorbol dibutyrate binding in vitro and in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:12604–12609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Murray NR, Davidson LA, Chapkin RS, Gustafson WC, et al. Overexpression of protein kinase C ßII induces colonic hyperproliferation and increased sensitivity to colon carcinogenesis. J. Cell. Biol. 1999;145:699–711. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nilsson Å. Metabolism of sphingomyelin in the intestinal tract of the rat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1968;76:575–584. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(68)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Inomata M, Ochiai A, Akimoto S, Kitano S, Hirohashi S. Alteration of beta-catenin expression in colonic epithelial cells of familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2213–2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kim JS, Crooks H, Foxworth A, Waldman T. Proof-of-principle: oncogenic ß-catenin is a valid molecular target for the development of pharmacological inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002;1:1355–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Van de Wetering, Sancho E, Verweij C, de Lau W, et al. The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kaiser S, Park YK, Halberg RB, Yu M, et al. Transcriptional recapitulation and subversion of embryonic colon development by mouse colon tumor models and human colon cancer. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R131. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Symolon H, Schmelz EM, Dillehay DL, Merrill AH., Jr. Dietary soy sphingolipids suppress tumorigenesis and gene expression in mouse models of colon cancer. J. Nutr. 2004;134:1157–1161. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kroesen BJ, Jacobs S, Pettus BJ, Sietsma H, et al. BcR-induced apoptosis involves differential regulation of C16 and C24-ceramide formation and sphingolipid-dependent activation of the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14723–14731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dbaibo GS, Wolff RA, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Activation of a retinoblastoma-protein-dependent pathway by sphingosine. Biochem. J. 1995;310:453–459. doi: 10.1042/bj3100453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Alesse E, Zazzeroni F, Angelucci A, Giannini G, et al. The growth arrest and downregulation of c-myc transcription induced by ceramide are related events dependent on p21 induction, Rb underphosphorylation and E2F sequestering. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:381–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kim DS, Kim SY, Kleuser B, Schafer-Korting M, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibits human keratinocyte proliferation via Akt/protein kinase B inactivation. Cell Signal. 2004;16:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mehta PP, Perez-Stable C, Nadji M, Mian M, et al. Suppression of human prostate cancer cell growth by forced expression of connexin genes. Dev. Genet. 1999;24:91–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)24:1/2<91::AID-DVG10>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhang ZQ, Zhang W, Wang NQ, Bani-Yaghoub M, et al. Suppression of tumorigenicity of human lung carcinoma cells after transfection with connexin43. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1889–1894. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.11.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].van der Heyden MA, Rook MB, Hermans MM, Rijksen G, et al. Identification of connexin43 as a functional target for Wnt signalling. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1741–1749. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.12.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hernadez-Blazquez FJ, Joazeiro PP, Omori Y, Yamasaki H. Control of intracellular movement of connexins by E-cadherin in murine skin papilloma cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 2001;270:235–247. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nishimura M, Saito T, Yamasaki H, Kudo R. Suppression of gap junctional intercellular communication via 5' CpG island methylation in promoter region of E-cadherin gene in endometrial cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1615–1623. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Roberts PC, Mottillo EP, Baxa AC, Heng HH, et al. Sequential molecular and cellular events during neoplastic progression: a mouse syngeneic ovarian cancer model. Neoplasia. 2005;7:944–956. doi: 10.1593/neo.05358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Murray NR, Weems C, Chen L, Leon J, et al. Protein kinase C betaII and TGFbetaRII in omega-3 fatty acid-mediated inhibition of colon carcinogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:915–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gökmen-Polar Y, Murray NR, Velasco MA, Gatalica Z, Fields AP. Elevated protein kinase C ßII is an early promotive event in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1375–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhang J, Anastasiadis PZ, Liu Y, Aubrey Thompson E, Fields AP. Protein kinase C beta II induces cell invasion through a RAS/MEK-, PKC/RAC 1-dependent signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:22118–22123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mutanen M, Pajari AM, Oikarinen SL. Beef induces and rye bran prevents the formation of intestinal polyps in Apc(Min) mice: relation to beta-catenin and PKC isozymes. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1167–1173. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.6.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang J, Alter N, Reed JC, Borner C, et al. Bcl-2 interrupts the ceramide-mediated pathway of cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5325–5328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hague A, Moorghen M, Hicks D, Chapman M, Paraskeva C. Bcl-2 expression in human colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Oncogene. 1994;9:3367–3370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ofner D, Riehemann K, Maier H, Riedmann B, et al. Immunohistochemically detectable bcl-2 expression in colorectal carcinoma: correlation with tumour stage and patient survival. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;72:981–985. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Manne U, Myers RB, Moron C, et al. Prognostic significance of bcl-2 expression and p53 nuclear accumulation in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 1997;74:346. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970620)74:3<346::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hanson CJ, Bootman MD, Distelhorst CW, Maraldi T, Roderick HL. The cellular concentration of Bcl-2 determines its pro- or anti-apoptotic effect. Cell Calcium. 2008 Jan 19; doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.014. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ruvolo PP, Clark W, Mumby M, et al. A functional role for the B56 alpha-subunit of protein phosphatase 2A in ceramide-mediated regulation of Bcl2 phosphorylation status and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:22847–22852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]