Abstract

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the liver that is characterized by progressive cholestasis and the development of secondary biliary cirrhosis. There is no widely recognized therapy for this disease, although anti-inflammatory agents (steroids), immunosuppressive agents (methotrexate), anti-fibrotics (colchicine), and choleretic agents (ursodeoxycholic acid) have been used in various small series. In the present study, Tacrolimus (FK 506), a new and powerful immunosuppressive macrolide antibiotic, has been used to treat 10 patients with PSC. Each subject had a liver biopsy, ERCP with visualization of the intra-and extrahepatic biliary tree, and a panel of hematological, serological, and biochemical laboratory tests before the initiation of the FK 506 therapy. The FK 506 was administered orally at 12-h intervals and was monitored by serial plasma FK 506 trough levels. After 360 days of treatment, the median serum bilirubin level was reduced by 75%, and the serum alkaline phosphatase was reduced by 70%. Moreover, the serum ALT and AST levels were reduced by 80 and 86%, respectively. No change in the serum level of BUN and creatinine levels occurred as a consequence of the FK 506 treatment These data demonstrate that: 1) FK 506 can be used to treat PSC; 2) the response to FK 506 by patients with PSC is rapid; and, 3) no adverse effect on the serum BUN and creatinine levels was observed. It is anticipated that FK 506 will become an important agent for the treatment of patients with PSC because of its powerful immunosuppressive activity.

INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the biliary tree that is characterized by a focal, albeit diffuse, destruction of the large- and medium-sized bile ducts (1–11). The disease is characterized pathophysiologically by cholestasis (1, 2). Endoscopically and histologically, biliary strictures and diverticula characterize the disease process (8–11).

The specific etiology of PSC is unknown, although because of its association with inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis but also Crohn’s colitis and HLA antigens B8, Dr3, and DrBW52, it is thought to be a disease of disordered immunity (12–21). As such, a variety of pharmacological agents directed at modifying the immune response have been used to treat PSC. These include antibiotics, bile acid absorbants, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressive agents (azathioprine, methotrexate, and d-penicillamine), and choleretic agents (cheno- and ursodeoxycholic acid), the latter two of which may also modulate the expression of HLA antigens on hepatobiliary epithelial cells (22–34). In advanced cases, liver transplantation has been used as a therapy (35–36). Moreover, resection of the damaged colon in cases of ulcerative colitis has been used, albeit unsuccessfully, to halt or ameliorate disease progression (37).

The present open-label preliminary study was initiated to investigate the efficacy and potential toxicity of Tacrolimus (FK 506), a powerful new macrolide antibiotic-possessing immunosuppressive activity, as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of PSC.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 10 subjects with a documented diagnosis of PSC were studied. Each had either an ERCP- or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram (PTHC)-confirmed diagnosis of PSC supported by the results of a percutaneous liver biopsy demonstrating a chronic inflammatory condition of the liver, particularly the portal areas with a characteristic pericholangiolar inflammatory and fibrotic reaction (11, 12).

Pretherapy evaluation

Each subject underwent a thorough pretherapy evaluation consisting of the following studies:

Complete blood count (CBC) with platelet count.

A panel of liver injury and function parameters to include total bilirubin, ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase (alk phos), γ glutamyl transpeptidase (γGTP), a serum protein electrophoresis, and a prothrombin time.

An endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram.

A percutaneous liver biopsy for histological evaluation.

A full colonoscopy to include multiple colonic biopsies from the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum to define the type and extent of any associated inflammatory bowel disease.

HLA typing.

BUN, creatinine, and creatinine clearance determinations.

CT scan of the liver for determination of the hepatic volume.

An ultrasound study of the liver, biliary tree, and portal and hepatic vessels.

Patient monitoring

After the pretherapy evaluation procedures were completed, each subject was given FK 506 at a starting dose of 0.075 mg/kg taken orally as two equally divided doses taken 12 h apart. The initial dose was either increased or decreased at 2-wk intervals to achieve a trough serum FK 506 level between 0.6 and 1.0 ng/ml. All FK 506 serum levels were obtained after an overnight fast and before the next morning’s dose (38).

Initially, all subjects were seen weekly (approximately four visits), then bi-weekly (2–3 visits), then monthly (2–3 visits), and finally quarterly, until a 1-yr study period was completed. At each visit, the following studies were obtained:

CBC with platelet count.

Electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, blood sugar.

A liver injury panel consisting of the serum bilirubin, AST, ALT, alk phos, and γGTP levels.

A serum FK 506 level.

At the end of a 1-yr study period, all of the studies performed as part of the prestudy evaluation were repeated. All liver biopsies were read blindly by pathologists unaware of the source of the biopsy study objectives.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the committee reviewing clinical research in human subjects at the University of Pittsburgh before its initiation.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as mean values ± SEM. All data were compared using the entry and exit measures. The Student’s t test and ANOVA were used for the statistical analyses. A p value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

A total of 10 subjects were enrolled in this open-label, preliminary study evaluating the efficacy and toxicity of FK 506 in the treatment of PSC. The demographic information in the 10 subjects studied is shown in Table 1. Most were male; 60% had co-existent ulcerative colitis, and all were positive for HLA antigens B8, Dr3, and DrBW52. The mean hepatic volume of the group was increased by 50% compared with normal values. The mean time required to achieve a stable serum level of FK 506 between 0.6 and 1.0 ng/ml and to maintain renal function at acceptable levels was 7.5 ± 2.5 wk. The mean FK dose prescribed on a daily basis was 10.5 ± 2.8 mg/day, whereas the mean daily dose on a per kg basis was 0.15 ± 0.04 mg/kg/day.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 10 Subjects Studied at Entry

| Parameter | Mean ± SEM | Range | Normal Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(yr) | 31.3 ± 4.3* | 18–58 | NA |

| Gender (M/F) | 7/3 | N/A | NA |

| White blood count (cells/mm3) | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 2.5–10.4 | 5–10 |

| Platelet count (cells/mm3) | 271 ± 45 | 90–621 | 150–300 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0.9–6.6 | <1.1 |

| AST(IU/1) | 172 ± 32 | 81–453 | <32 |

| ALT(IU/1) | 258 ± 57 | 73–712 | <32 |

| Alk phos (IU/1) | 422 ± 93 | 190–1233 | <125 |

| γGTP (IU/1) | 688 ± 182 | 210–2634 | <35 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 12.8 ± 1.3 | 4.1–21 | 10 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.4–1.6 | <1.2 |

| Ulcerative colitis (N) | 6 | NA | — |

| Crohn’s colitis (N) | 2 | NA | — |

| Hepatic volume (ml) | 1837 ± 216 | — | 1225 ± 250 |

| HLA B8-positive | 10 | NA | NA |

| HLA Dr3-positive | 10 | NA | NA |

| HLA DrBW52 | 10 | NA | NA |

Values are means ± SEM.

NA, not applicable.

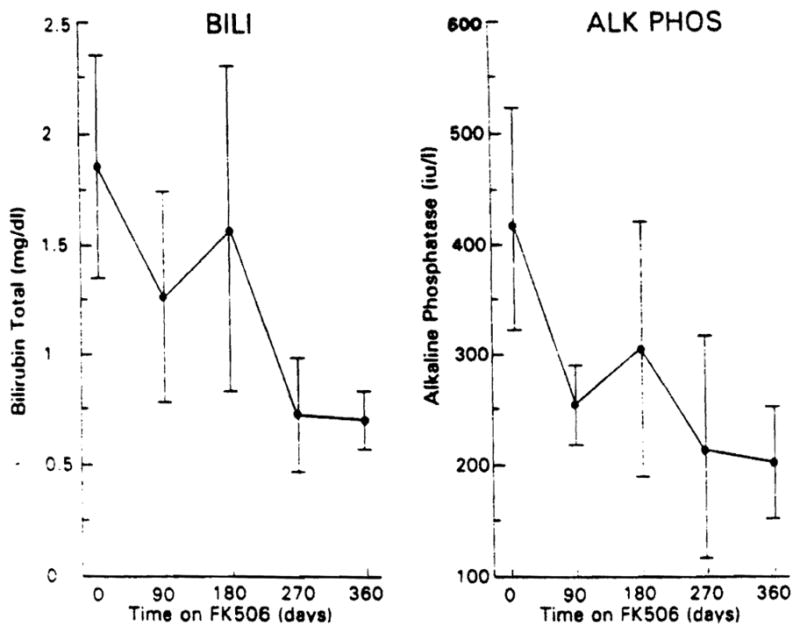

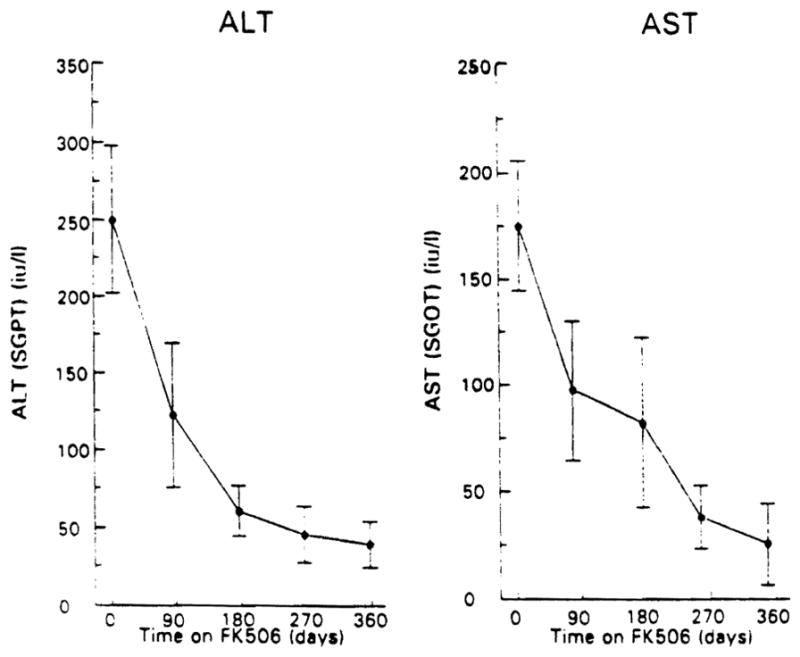

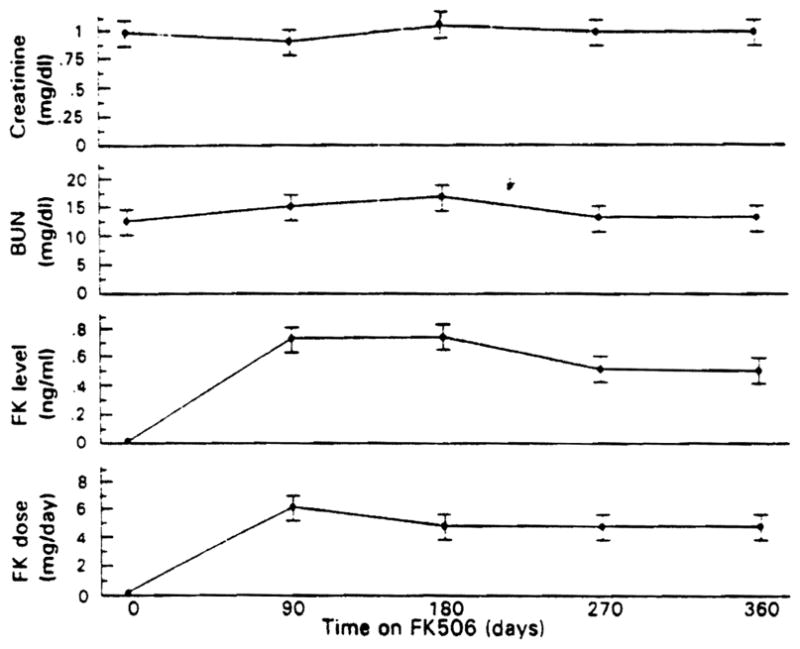

Associated with FK 506 treatment, the serum alk phos and bilirubin levels fell, as shown in Figure 1. The alk phos level declined by more than 50% from a level 3.5 times normal to 1.5 times normal (p < 0.01). The serum bilirubin level returned to the normal range (p < 0.01). Figure 2 and Table 2 show the data for serum bilirubin, AST, and ALT. Both enzymes fell markedly with FK 506 treatment to levels just outside and inside the normal range, respectively (p < 0.01). The BUN level increased minimally, whereas the serum creatinine level remained unchanged. The changes in the serum BUN and creatinine levels at quarterly intervals are shown in Figure 3 along with the plasma FK 506 levels and the dose administered.

Fig. 1.

Serum total bilirubin and alk phos levels with increasing time through 1 yr on FK 506 in the 10 subjects studied. The points are mean values; the brackets represent the SEM.

Fig. 2.

Serum ALT and AST levels with increasing time through 1 yr on FK 506 in the 10 subjects studied. The points are mean values; the brackets represent the SEM.

Table 2.

Initial and 1-Yr Clinical Characteristics of the Patients Studied

| Parameters | Initial Result | 1-Yr Result | Normal Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | <1.1 |

| AST(IU/1) | 172 ±32 | 35 ± 20 | <32 |

| ALT(IU/1) | 258 ±57 | 40 ± 15 | <32 |

| Alk phos (U/1) | 420 ±93 | 200 ± 50 | <125 |

| Protime (s) | 13.2 ± 1.0 | 13.0 ± 1.0 | 11.0 |

| White blood count (×103) | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 5–10 |

| Platelets (×103) | 271 ± 45 | 228 ± 30 | 150–300 |

| CT liver volume (ml) | 1820 ± 230 | 1880 ± 210 | 1000–1500 |

Fig. 3.

Serum BUN and creatinine levels in the 10 subjects studied as well as the FK 506 dose and plasma levels with increasing time through 1 yr on FK 506. Values are mean ± SEM.

No changes in the hepatic volume or ERCP findings were observed over the course of the 1-yr of FK 506 therapy. Similarly, no change in the colonoscopic findings were observed over the 1-yr course of FK 506 therapy. The patients did report a reduction in pruritis grade (p < 0.05) and frequency of bowel movements (p < 0.05) associated with the use of FK 506 compared with pre-FK 506 levels.

When the liver biopsies obtained pre- and post-1 yr of FK 506 therapy were compared in a blinded fashion, little or no statistical difference was seen between the two biopsies. Thus, although this was no histological regression, there also was no identifiable progression.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report on the use of FK 506, a macrolide antibiotic isolated from streptomyces tsukubaenis that has powerful immunosuppressive activity that has been estimated to be 10–100 times more powerful than cyclosporine when it has been studied in various in vitro assay systems assessing T cell functional activity (39).

FK 506 has been studied extensively in transplant patients, including those with liver, kidney, and intestinal grafts (40–42). In each case, FK 506 has been shown to be at least as good, if not better, than cyclosporine at preventing allograft rejection (40–42). Unlike cyclosporine, increasing doses of FK 506 can be used to treat an acute cellular rejection episode (44–47). Moreover, FK 506, unlike cyclosporine, has been shown to be capable of reversing early chronic allograft rejection (44–47)

These unique advantages of FK 506 and its relative ease of administration, coupled with the ability to monitor its blood levels and adjust the dosing schedule as necessary to either enhance efficacy or reduce toxicity, have made it a particularly attractive agent for the clinical treatment of a variety of putative autoimmune diseases. PSC is one of these diseases.

As shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3 and in Table 2, FK 506 has been shown to be very effective at controlling the relentless biliary destruction and cholestasis that characterizes PSC as assessed biochemically. The serum levels of alk phos, bilirubin, and both aminotransferases fell rapidly to either normal or near normal values.

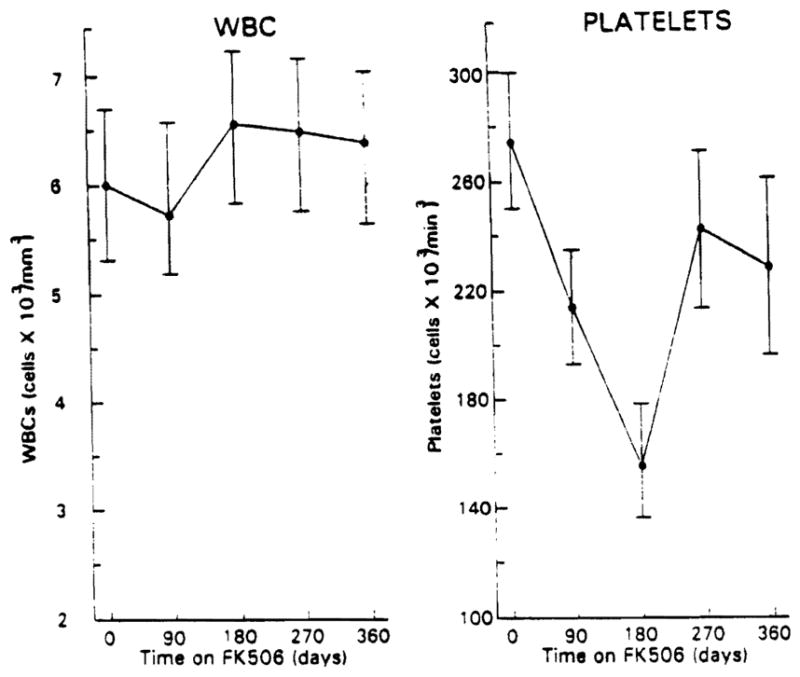

The cost of this improvement in the course of PSC in terms of drug toxicity has been mild to nonexistent as shown in Figures 3 and 4. Only minor changes in renal function and a transient fall in the platelet count were observed in response to FK 506 treatment.

Fig. 4.

White blood cell counts and platelet counts in the 10 patients studied are shown with increasing time through 1 yr on FK 506. Values are mean ± SEM.

Moreover, the immunosuppressive activity of FK 506 had the added advantage, not directly assessed as part of this study but nonetheless obvious to the physicians and surgeons caring for these patients, that the enhanced control of their liver disease was associated with control of underlying inflammatory bowel disease. It should be pointed out, however, that improvement in the various biochemical values used to assess hepatic injury may not be adequate in defining the long term clinical course of a disease such as primary sclerosing cholangitis. The effects on survival, the need for transplantation, longer term changes on hepatic biopsy, and, possibly, changes on cholangiography may all be more important parameters to be assessed in future studies.

Nonetheless, based on this preliminary open-label trial evaluating the efficacy of FK 506 in the clinical management of PSC, the investigators believe that a randomized controlled study comparing FK 506 to ursodeoxycholic acid or possibly methotrexate is indicated. These latter two agents also have been reported to be efficacious in cases of PSC, the former in several small trials and the latter in a trial from a single institution. The effects achieved with both of these other agents have been assessed primarily on the basis of clinical parameters. Nonetheless, based on the evidence available, each appears to be somewhat effective. Only by a direct comparison, probably as a result of a multi-center trial, will the practitioner be able to make a rational choice between these new agents.

References

- 1.Wiesner RH, LaRusso NF. Clinicopathologic features of the syndrome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:200–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman RW, Arborgh BA, Rhodes JM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: A review of its clinical features, cholangiography and hepatic histology. Gut. 1980;21:870–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.10.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrupf E, Fansa O, Kolnanmskog F. Sclerosing cholangitis in ulcerative colitis: A follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17:33–9. doi: 10.3109/00365528209181041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:899–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404053101407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherlock S. The syndrome of disappearing bile ducts. Lancet. 1987;2:493–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91802-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ludwig J, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH. The syndrome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Prog Liver Dis. 1990;9:555–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindor KD, Wiesner RH, MacCarty RL, LaRusso NF. Advances in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Med. 1990;89:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90101-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elias E, Summerfield JA, Dick R, Sherlock S. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis of jaundice associated with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1974;67:907–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacCarty RL, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Findings on cholangiography and pancreatography. Radiology. 1983;149:39–44. doi: 10.1148/radiology.149.1.6412283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacCarty RL, LaRusso NF, May GR. Cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitic cholangiographic appearance. Radiology. 1985;156:43–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.1.2988012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig J, Barham SS, LaRusso NF. Morphologic features of chronic hepatitis associated with sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:632–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenheimer HC, LaRusso NF, Thayer WP., Jr Elevated circulating immune complexes in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 1983;3:150–4. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman RW, Varghese Z, Gaul R. Association of primary sclerosing cholangitis with HLA B8. Gut. 1983;24:38–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quigley EMM, LaRusso NF, Ludwig J. Familiar occurrence of primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:1160–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiteside TL, Lasky S, Si L, Van Thiel DH. Immunologic analysis of mononuclear cells in liver tissue and blood of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hapatology. 1985;5:468–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jorge AD, Esley C, Alumada J. Family incidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with immunological diseases. Endoscopy. 1987;19:114–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman RW, Kelly P, Heryst A. Experience of HLA Dr antigens in the bile duct epithelium in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1988;29:422–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.4.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samaldi G, Donaldson PT, Margin S. Activation of the complement system in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1430–4. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snook JA, Chapman RW, Fleming K, Jewell DP. Anti-neutrophil nuclear antibody in ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;76:30–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mieli-Vergani G, Lobo Yeo A, Mac Farlane DM. Different immune mechanisms leading to autoimmunity in primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune chronic active hepatitis of childhood. Hepatology. 1989;9:198–207. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prochazka EJ, Terasaki PI, Mi SK, Park DVM. Association of primary sclerosing cholangitis with HLA DrW52a. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1842–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006283222603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rankin JG, Boden RW, Goulston SJM. The liver in ulcerative colitis. Treatment of pericholangitis with tetracycline. Lancet. 1950;2:1110–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(59)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polter DE, Grabl V, Eigenbrodt EH, Combes B. Beneficial effect of cholestyramine in sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1989;79:326–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers RN, Cooper JH, Padis N. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Complete gross and histologic renewal after long term steroid therapy. Am J Gastroenterology. 1970;57:527–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mistilis SP, Skring AP, Goulston SJ. Effect of long term tetracycline therapy, steroid therapy and colectomy in pericholangitis for chronic ulcerative colitis as the natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:790–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J. Prospective trial of penicillamine in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindor KD, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH. Penicillamine and colchicine are not of benefit after ten years in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 1989;10:638. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner A. Azathioprine treatment in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 1971;2:663–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)80107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javett SL. Azathioprine in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 1971;1:810. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan MM, Arora S, Pincus SH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and low dose oral pulse methotrexate therapy. Clinical and histologic responses. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:231–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-2-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stiehl A, Roedsch R, Theilmann L, Galle P. The effect of ursodeoxycholic acid in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:664. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Brien CB, Senior JR, Arora-Mirchandani R, Batta AK, Salen G. Ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis: A 30-month pilot study. Hepatology. 1991;14:838–47. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840140516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayashi H, Higuchi T, Ichimaiya H, Hishida N, Sakamoto N. Asymptomatic primary sclerosing cholangitis treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:533–5. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beuers U, Spengler U, Kruis W, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid for treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis: A placebo-controlled trial. Hapatology. 1992;16:707–14. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langnas AN, Grazi GG, Stratta RJ. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: The emerging role for liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterology. 1990;85:1136–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marsh JW, Iwatsuki S, Makowka L. Orthotopic liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Surg. 1988;207:21–5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198801000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Congenis JR, Wiesner RH, Beaur SJ. Effect of proctocolectomy for chronic ulcerative colitis on the natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:790–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi M, Tamura K, Katayama N, et al. FK 506 assay past and present characteristics of FK 506 ELISA. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2725–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goto T, Kino T, Hatanaka H, Okuhara M, Kohsaka M, Aoki ZH, Imanaka H. FK 506: Historical perspectives. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2713–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fung J, Abu-Elmagd K, Jain A, et al. A randomized trial of primary liver transplantation under immunosuppression with FK 506 vs. cyclosporine. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2977–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro R, Jordan M, Scantlebury V, et al. FK 506 in clinical kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:3065–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todo S, Tzakis A, Reyes J, et al. Clinical small bowel or small bowel plus liver transplantation under FK 506. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:3093–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winkler M, Ringe B, Gerstenkorn C, et al. Use of FK 506 for treatment of chronic rejection after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2984–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Alessandro AM, Kalayoglu M, Pirsch JD, et al. FK 506 rescue therapy for resistant rejection episodes in liver transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2987–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis WD, Jenkins RL, Burke PA, et al. FK 506 rescue therapy in liver transplant recipients with drug-resistant rejection. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2989–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodle ES, Perdrizet GA, Brunt EM, et al. FK 506: Reversal of humorally mediated rejection following ABO-incompatible liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2992–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw BW, Jr, Markin R, Stratta R, Langnas A, Donovan J, Sorrell M. FK 506 rescue treatment of acute and chronic rejection of liver allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:2994–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]