Abstract

Background & Purpose

Given the extensive literature on body weight supported treadmill training (BWSTT) in adult rehabilitation, a systematic review was undertaken to explore the strength, quality and conclusiveness of the scientific evidence supporting the use of treadmill training and body weight support in those with pediatric motor disabilities. A secondary goal was to ascertain whether sufficient protocol guidelines for BWSTT are as yet available to guide pediatric physical therapy practice.

Methods

The database search included MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database), Cochrane Library databases, and ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) from January 1, 1980 until May 31, 2008 for all articles that included treadmill training and body weight support alone or in combination for individuals under 21 years of age, with or at risk for having a motor disability. We identified 277 unique articles from which 29 met all inclusion criteria

Results

Efficacy of treadmill training in accelerating walking development in Down syndrome has been well-demonstrated. Evidence supporting the efficacy or effectiveness of BWSTT in pediatric practice for improving gait impairments and level of activity and participation in those with cerebral palsy, spinal cord injuries, and other central nervous system disorders remains insufficient even though many studies noted positive, yet small, effects. Increased use of randomized designs, studies with treadmill training only groups, and dosage studies are needed before practice guidelines can be formulated. Neural changes in response to training warrant greater exploration, especially given the capacity for change in developing nervous systems.

Discussion and Conclusion

Large scale controlled trials are critically needed to support the use of BWSTT in specific pediatric patient sub-groups and to define optimal protocol parameters.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, Down syndrome, gait, walking, therapy

Background

Promoting or restoring ambulation in children and adults with motor disabilities has long been a major goal of physical therapy for those deemed to have the potential to achieve this goal. Traditionally, patients who could not walk independently practiced this skill, using orthoses when necessary, in parallel bars or with assistive devices that moved with the patient, such as walkers, canes and crutches, and/or with supervision or support from up to two therapists or other health professionals or family members. Those who needed more support than this simply did not practice walking unless or until their motor status improved sufficiently as a result of development, exercise, or recovery. Motorized treadmills have long been utilized as an aerobic exercise device in healthy populations but since good walking stability is a prerequisite for their use, these had been used infrequently in physical therapy practice, particularly for parsons with neurological disabilities.

Animal studies of supported treadmill training producing coordinated stepping movements in spinalized cats that lead ultimately to the incredible discovery that this was also possible in humans with complete spinal cord injuries (SCI) 1. To facilitate step training, weight-support systems for treadmills were developed which drastically reduced the postural requirements, and hence the amount of physical assistance, needed to safely participate in ambulation training and to help encourage more appropriate motor patterns. As a result, rehabilitation practices were transformed for those with SCI2 and for those post-stroke3, with multiple studies focusing on therapist- or machine-assisted step training in these populations.

However, the evidence supporting this rapidly expanding clinical approach may not be as strong as some presume. A recent Cochrane review in stroke reviewed the evidence from 15 randomized trials on treadmill training and body weight support in the treatment of walking limitations after stroke, found no statistically significant differences between treadmill training, regardless of body weight support, and over ground training for improving walking speed or dependence 4. The data from individual trials indicated that task-specific practice, not the treadmill per se, was the active ingredient in producing functional improvements in gait. Lam et al5 (2007) performed a systematic review of the efficacy of gait rehabilitation strategies for those with SCI and echoed this conclusion. Lower level evidence (non-randomized studies) did show some support for BWSTT in chronic SCI by showing that these programs did improve aspects of functioning. However, their review revealed that there was strong support for comparable outcomes from body weight supported treadmill training and over ground walking practice in subacute SCI when intensity was equivalent. The Cochrane Review in the stroke population also recommended further investigation, since some individual studies suggested that treadmill training with body weight support was superior to treadmill training alone. The addition of body weight support makes repetitive training far more feasible for a broader range of clients and allows for more flexibility in terms of optimizing speed and training kinematic patterns for those with weakness or other impairments limiting their gait function by increasing safety and decreasing the physical work necessary by one or more therapists..

Widespread clinical and research interest in locomotor training in adult neurological rehabilitation has now infiltrated pediatric physical therapy practice for children with delayed or reduced gait function. Pediatric research on the effectiveness or efficacy of locomotor-based training devices and protocols has lagged behind their clinical incorporation, with practitioners relying primarily on evidence and guidelines from the adult literature since that is what was available to them. A review on this topic was published in 20066. Of the fifteen studies uncovered by the literature search, seven were abstracts, and one appeared in a physical therapy news magazine, leaving only seven studies of BWSTT in children with motor disabilities that were published as research reports in peer-reviewed scientific journals. The authors concluded that with the limited and relatively low level of evidence, the current research does not support the effectiveness of treadmill training. Since weight supported treadmill training provides opportunities for physical training of lower extremity strength and endurance, and repetitive task (and/or speed) - specific training of stepping, each of which are consistent with principles in the exercise physiology and motor control literature, respectively, and since research and clinical interest in this approach has increased substantially in recent years, we felt it was important to revisit this topic. Therefore, the goal of this paper was to substantially enhance the previous search to include the rapidly accumulating scientific literature on this topic and to investigate the evidence supporting treadmill training with and without body weight support across broader diagnostic categories within pediatric neurorehabilitation. A secondary goal was to ascertain whether sufficient protocol guidelines are available to guide practice in certain patient groups. We also expanded the scope compared to the previous pediatric review to include infants, children and young adults (less than 21 years of age) with medical diagnoses in which a motor disability was a consistent and/or prominent feature.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

As stated above, the search aimed to include all studies that investigated outcomes of treadmill training and body weight supported gait training, used separately or in combination. We chose not to eliminate studies where other treatments were administered or permitted at the same time. The review was restricted to those studies with the primary goals of improving lower extremity motor functioning including: increasing step counts, rate or coordination on the treadmill, increasing over ground gait speed, symmetry or coordination, decreasing need for assistance when walking, or more generally promoting lower extremity gross motor skill development or task performance. Studies that aimed solely to improve aerobic fitness or to decrease body weight through greater caloric expenditure were excluded.

The population of interest was infants, children, adolescents and young adults less than 21 years of age who had, or were at risk for developing, a motor disability affecting gait coordination or function. We did not include studies of typically developing children, those that used treadmills for sports-related training, or those that addressed diminished exercise capacity due to asthma, cystic fibrosis, obesity, or acute medical illness. In studies that also included individuals 21 years or over, we only included those studies that provided individual data or separate analyses for those less than 21 years of age.

The review was limited to studies published in peer-reviewed journals with full text available in English. All research reports were accepted, regardless of study design. We excluded studies published only in abstract or dissertation form, as well as those investigating only the within-session effects of different walking conditions. Review articles on related topics were also excluded.

Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive systematic literature search to identify all relevant articles. Both authors first received training in electronic search methods and strategies from a medical librarian. The following databases were searched covering the time span from January 1, 1980 until May 31, 2008: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database), all databases within the Cochrane Library, and ERIC (Education Resources Information Center). We chose 1980 as the lower cut-off, since body weight supported treadmill training in humans did not emerge until the early to mid 1980s, following related discoveries made through animal research.

The EMBASE.com web-based search platform was used to simultaneously search the EMBASE and MEDLINE bibliographic databases. For each search term, selected options included mapping to preferred terminology (with spell check), and searching also for synonyms, with explosion on preferred terminology. Records were limited to Humans, In English, and Records added between January 1, 1980 and May 31, 2008. We searched PEDro for records that included either ‘treadmill’ or ‘weight support’ in the abstract/title field, within the sub discipline ‘pediatrics’. All other searches were limited to English language publications between January 1980 and May 2008, and the strategy listed below was employed:

treadmill

locomotor

‘over ground’

overground

‘weight support’

harness NOT Pavlik

robotic NOT surgery

#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7

infant OR child OR adolescent

training

#8 AND #9 AND #10

#11 NOT obese

The EMBASE/MEDLINE search returned 163 unique citations. As we proceeded sequentially through the list of databases and eliminated any previously identified citations, 32 additional unique citations were identified by CINAHL, 69 by the Cochrane Library, eight by PEDro, and four by ERIC. One additional relevant citation was found through examination of reference lists. These 277 unique citations were then examined further.

Each author independently screened each title and abstract to determine whether criteria for inclusion were potentially met. Selection results from the two authors were compared, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. None required a third reviewer in order to reach a decision. With this process, we eliminated 218 articles that did not report outcomes of treadmill and/or partial body weight supported gait training for individuals under 21 years of age with motor disabilities. Thirteen abstracts, two dissertations, three review articles, and two reports published in non-peer-reviewed journals were also excluded.

We then retrieved the remaining 39 full text articles that potentially met the search criteria, and each author reviewed each article separately. Three studies were excluded because no subjects under 21 years of age participated. Six included both pediatric and adult subjects, but were excluded from this review because data from the pediatric subjects were not reported separately. One study was eliminated because it compared different treadmill walking conditions within a single session. The remaining 29 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Both authors independently read each article, rated each using the PEDro scale8 (http://www.pedro.fhs.usyd.edu.au/scale_item.html#scale_1), and extracted data using the form provided on the website of the American Academy of Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM) as a guide (http://www.aacpdm.org). A consensus process was used to finalize the level and quality of evidence rating presented here.

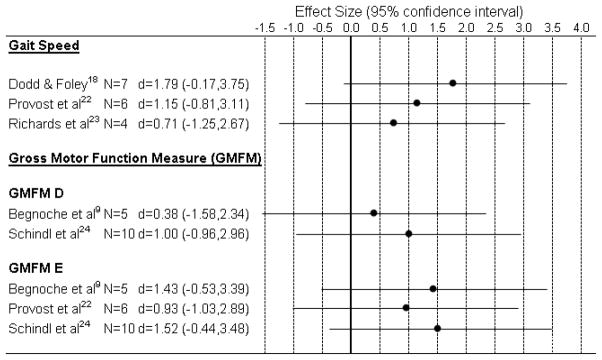

Effect sizes were calculated for the three most common outcome measures in the group with CNS impairments: self-selected gait velocity, GMFM D and GMFM E, and only those studies that had the necessary data within the manuscript to compute effect sizes could be included. This was not done for the SCI group because of the predominance of case reports rather than group data, or for the Down syndrome group since the primary outcome there differed across studies. Effect sizes were calculated by: 1) the difference in mean change scores across treatment groups divided by the standard deviation of the mean change score in the control group, or 2) the mean change as a result of the intervention of interest divided by its standard deviation.

Results

A general description of all 29 included studies9–37 is provided in Table 1, including the basic study design, number and characteristics of the participants, outcome measures used, and summarized results. The information in Table 2 focuses more specifically on the intervention details including the parameters of the treadmill training such as speed and duration, type and amount of body weight support provided, if any, and a description of other concurrent interventions that may have been provided or that the patient was permitted to continue during the study period. These are separated by the three patient groupings that emerged in this review: 1) those with cerebral palsy and other central motor impairments, 2) those with spinal cord injuries; and 3) infants with Down syndrome. None of the studies used body weight support without a treadmill, although not all treadmill studies included the use of body weight support for all participants.10,19,24 In most cases, the two intervention strategies were used in combination. The level and quality of evidence of the identified studies is summarized in Tables 3–5. Sackett’s Levels of Evidence38 (Table 3) was used to determine the strength of the evidence and the PEDro rating instrument8 (Table 4) was used to rate the quality of the studies. The level of evidence and quality rating for each of the included studies is listed in Table 5.

Table 1.

Description of study design, participants, outcomes measures and results by study

| First Author Year |

Design | Sample size, Gender, Age Mean (SD) | Diagnosis, Mobility Level | Assessment Schedule, Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral Palsy/Other Central Motor Impairments | |||||

| Begnoche 20079 |

Prospective cohort, no control group | n=5 4M, 1F 6.8 (3.0) y |

Spastic CP, 4 diplegia, 1 quadriplegia, 2 GMFCS Level I, 1 Level III, 2 Level IV | 0,4 wks, training during wks 1–4 | |

| GMFM total score, PEDI, 10 m Walk Test | NS | ||||

| Step length, stride length, base of support | NS | ||||

| Step length differential | ↓ post vs. pre | ||||

| Blundell 200310 |

ABA, Nonrandomized | n=8 7M, 1F 6.3 (1.3) y |

CP, 7 spastic diplegia, 1 spastic/ataxic quadriplegia, Ambulatory | 0,2,6,14 wks, training during wks 3–6 | |

| Isometric strength at hip, knee, ankle | ↑ post vs. pre for 7 of 12 muscle groups, otherwise NS | ||||

| Lateral Step-up Test | ↑ post vs. pre, otherwise NS | ||||

| Motor Assessment Scale, sit-to-stand | ↑ post vs. pre, otherwise NS | ||||

| 10 m Walk Test | ↑ stride length, ↓ time to walk 10 m, otherwise NS | ||||

| 2 min Walk Test, 9-hole peg test | NS | ||||

| Bodkin 200311 |

Case report | n=1 1M 7m 28d 5m 7d CA |

Premature birth at 29 wks gestation, Grade III/IV IVH on left, BPD Motor skills < 5th %ile |

AIMS after 0,7,14,19 wks of training, follow-up every 6wks until wk 52 Videotaping of treadmill stepping at 10, 15, 20 cm/sec, weekly during training (wk 0–23), then every other wk until wk 52 | Steady progress, continued below 5th %ile for CA Total # of steps ↑ at faster rate during training vs. follow- up. % of steps that were alternating vs. single, parallel, or double ↑ during training, maintained afterward. % of steps with initial contact on toe ↓ during training, ↑ afterward. |

| Borggraefe 200812 |

Case report | n=1 1M 6y |

Bilateral spastic CP GMFCS Level III |

0, 3wks, ~20 wks, training during wks 1–3 | |

| 10 m Walk Test, GMFM D and E | ↑ post vs. pre, almost preserved at follow up | ||||

| 6 min Walk Test | ↑ post vs. pre, ↑ post vs. follow up | ||||

| Modified Ashworth Scale, LE muscles | Bilateral hamstring score ↓ post vs. pre, otherwise same | ||||

| GMFCS Level | No change | ||||

| Cernak 200813 |

Case report | n=1 1F 13 y |

Cerebellar ataxia 16 m following brainstem infarct Required maximal assistance of 2 to walk |

0,1,2,6 mo, training during mo 1 and 3–6 | |

| Gillette Functional Walking Scale | ↑ during 2nd training interval, otherwise same | ||||

| WeeFIM transfers subscale | ↑ during both training intervals, otherwise same | ||||

| WeeFIM mobility subscale | ↑ during 2nd training interval, otherwise same | ||||

| # of unassisted steps on treadmill | ↑ during all intervals | ||||

| Chan 200414 |

ABA, randomized comparison of two treatments | TT group: n=6, 5M, 1F 6.3 (1.0) y TT+NMES group: n=6, 4M, 2F 6.5 (2.7) y |

TT: 2 spastic diplegia, 4 spastic hemiplegia, TT+NMES: 5 spastic diplegia, 1 spastic hemiplegia, All were independent walkers, with equinus | 0,2,4,6,8 wks, training during wks 3–6 | |

| Ankle moment quotient | NS | ||||

| Ankle power quotient | NS | ||||

| GMFM D and E |

↑ post vs. pre in both groups during training, maintained afterward NS group differences |

||||

| Cherng 200715 |

Prospective cohort, assigned to AB or BA schedule | AB group n=4, 2M, 2F 4.8 (1.3) y BA group n=4, 4M, 0F 4.2 (0.8) y |

Spastic diplegic CP, AB: 1 GMFCS Level II, 3 Level III BA: 1 GMFCS Level II, 3 Level III |

0,12,24 wks, training during wks 13–24 for AB, and during wks 1–12 for BA | |

| Stride length, % double limb support, velocity, cadence | ↑ post vs. pre stride length, ↑ post vs. pre in % double limb support approached significance, otherwise NS | ||||

| GMFM Total, A, B, C, D, E | ↑ post vs. pre for Total, D and E, otherwise NS | ||||

| MAS, Dorsiflexion selective motor control | NS | ||||

| Day 200416 |

Case report | n=1 1M 9y 5m |

Spastic tetraplegic CP nonambulatory, able to stand using walker, KAFOs, and assistance | 0,25 wks, training during wks 1–25 | |

| GMFM Total, Goal (D&E), A, B, C, D, E | ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| PEDI Mobility functional skills | ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| PEDI caregiver assistance | ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| Subjective reports (PTs and OTs) | Positive changes in affect, motivation, attention | ||||

| DeBode 200717 |

Controlled trial nonrandomized | Hemi-TT group n=12, 8M, 4F, 13 (2.5) y Hemi-control group n=2, 1F, 1M 13–14 y |

Hemispherectomy due to prenatal stroke, cortical dysplasia, or Rasmussen syndrome | 0,2 wks, training during wks 1–2 | |

| Motor portion of Fugl-Meyer LE scale | NS | ||||

| Paretic leg stance time | NS | ||||

| Usual and fast walking velocity, 15.2 m | NS | ||||

| fMRI of active ankle dorsiflexion (3 Hemi-TT subjects vs. 2 Hemi-controls and 2 healthy controls, ages 10–12 y) | ↑ spatial extent & intensity of activated voxels in S1M1, SMA, Cing, and SII, in Hemi-TT group. No change in Hemi-controls. No change or ↓ in healthy controls | ||||

| Subjective reports (subjects, parents, PTs) | Reports of improved gait patterns, strength, motor control | ||||

| Dodd 200718 |

Matched pairs controlled trial, nonrandomized | TT group n=7, 5M, 2F 8.4 (2.5) y Control group n=7 5M, 2F 9.4 (2.8) |

CP Each group included 4 athetoid quadriplegia, 1 spastic diplegia, 2 spastic quadriplegia, 2 GMFCS Level III, 5 Level IV |

0,6 wks, training during wks 1–6 | |

| 10 m Walk Test | ↑ post vs. pre in TT group, ↑ in TT group vs. Control | ||||

| 10 min Walk Test | NS, group difference approached significance | ||||

| Lotan 200419 |

Prospective cohort, no control group, AB | n=4 0M, 4F mean 10 y (range 8.5–11) |

Rett syndrome, Stage III, independent mobility | 0,2,4 mo, training during mo 2–4 | |

| Resting heart rate | ↓ during training interval, NS during control interval | ||||

| Heart rate while treadmill walking at 42 cm/s with no incline | ↓ during training interval approached significance, NS during control interval | ||||

| 31-item motor-functioning tool | ↑ during training interval, total and 4 individual items | ||||

| Meyer-Heim 200720 |

Prospective, two cohorts, no control group | Inpatient group n=15 9M, 6F 11.2 (4.3) y Outpatient group n=9 6M, 3F 8.2 (2.9) y |

Inpatient: 7 bilateral & 1 unilateral spastic CP, 2 Guillain-Barre, 2 incomplete paraplegia, 1 stroke, 1 dystonic CP, 1 encephalitis Outpatient: 9 bilateral spastic CP GMFCS Levels I – IV |

Pre, post (# of wks not reported) | |

| 10 m Walk Test | ↑ post vs. pre for both groups | ||||

| 6 min. Walk Test (inpatients only) | ↑ post vs. pre for inpatient group, not tested in outpatients | ||||

| Functional Ambulation Category | ↑ post vs. pre for inpatient group, NS for outpatient group | ||||

| GMFM D | ↑ post vs. pre for both groups | ||||

| GMFM E | ↑ post vs. pre for inpatient group, NS for outpatient group (↑ post vs. pre for outpatient group if 1 subject excluded) | ||||

| Phillips 200721 |

Prospective cohort, no control group | n=6 4M, 2F 10.5 (3.3) y 3 subjects had usable fMRI data, 2M, 1F 11.3 (3.1) y |

Spastic CP, 4 hemiplegia, 2 asymmetrical diplegia All GMFCS Level I (Same sample as Provost 2007) 3 had usable fMRI data: 2 hemiplegia, 1diplegia |

0,2 wks, training during wks 1–2 | Group results as reported by Provost 2007 |

| 10 m Walk Test | ↑ post vs. pre for each of the 3 subjects with usable fMRI | ||||

| 6 min Walk Test | ↑ post vs. pre for 2 of the 3 subjects with usable fMRI | ||||

| fMRI region of interest and functional analysis during active ankle dorsiflexion and during finger tapping as a control | ↑ total fMRI activation for both tasks Subject 1: ↑ 46% ankle, ↑ 76% finger Subject 2: ↑ 366% ankle, ↑ 58% finger Subject 3: ↑ 939% ankle, ↑ 36 % finger Greatest increase in cortical activation at contralateral S1M1 for subjects 1 and 3, bilateral SMA for subject 2 |

||||

| Provost 200722 |

Prospective cohort, no control group | n=6 4M, 2F 10.5 (3.3) y |

Spastic CP, 4 hemiplegia, 2 asymmetrical diplegia All GMFCS Level I |

0,2 wks, training during wks 1–2 | |

| 10 m Walk Test | ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| Energy Expenditure Index | ↓ post vs. pre | ||||

| 6 min Walk Test, single leg stance time | NS | ||||

| GMFM E | NS | ||||

| Richards 199723 |

Prospective cohort, no control group | n=4 1M, 3F 2.0 (0.3) y |

Spastic CP, 2 diplegia, 1 hemiplegia, 1 tetraplegia, 2 walked with manual support, 2 unable to step when supported | 0,2,4 mo, training during mo 1–4 | |

| GMFM total score | ↑ during each interval for each subject | ||||

| SWAPS | ↑ for 2 of 4 subjects after 2 m, ↑ for each subject after 4 m | ||||

| Gait videographic test (velocity, stride length and cadence) | After 2 m, ↑ velocity for 2 subjects, ↓ for 2 After 4 m, ↑ velocity for 2 subjects, minimal change for 2 |

||||

| Full gait analysis, (1 subject compared to 1 age matched typically developing child) | Improved hip and ankle kinematics, ↓ coactivation, improved triceps surae activation profile | ||||

| Schindl 200024 |

Prospective cohort, no control group, multiple baseline | n=10 4M, 6F 11.5 (4.3) y |

Spastic CP, 3 diplegia, 4 tetraplegia, 3spastic/ataxic tetraplegia 6 FAC 0, 2 FAC 2, 1 FAC 3, 1 FAC 4 | 0,3,6,18 wks, training during wks 7–18 | |

| Functional Ambulation Category | ↑ post vs. pre, NS during baseline intervals | ||||

| GMFM D and E | ↑ post vs. pre, NS during baseline intervals | ||||

| Subjective impressions of subjects and caregivers | 8 enjoyed training and reported improved motor abilities, 2 found training exhausting, noted no change in function | ||||

| Seif Naraghi 199925 |

Case report | n=1, 1M 18 y |

4 y post TBI | 0,4 mo, training during mo 1–4 Walking ability |

↑ walking ability from use of wide base quad cane with guarding to independent use of straight cane. |

| Down Syndrome | |||||

| Angulo-Barroso 2008a26 |

Developmental, randomized comparison of two treatment protocols, with follow-up | LG: n=14 5M, 9F 10.4 (2.2) m HI: n=16 13M, 3F 9.7 (1.6) m |

Down syndrome, Delayed motor development (same sample as Ulrich 2008) | Every 2 m during training, then 3,6,9,15 m Actiwatch activity monitors for 24 hrs |

|

| Trunk and leg low activity duration |

↓ in HI group vs. LG Group difference maintained for 15 m after training |

||||

| Trunk and leg high activity duration | ↑ in HI group vs. LG, ↑ in HI group during last 3 quintiles of training, no change over time in LG group, Group difference maintained for 15 m after training | ||||

| Angulo-Barroso 2008b27 |

Follow-up of developmental, randomized comparison of two treatment protocols | LG: n=13 4M, 9F HI: n=12 9M, 3F ages of subsample not reported |

Down syndrome Delayed motor development (subsample of Ulrich 2008) |

3,6,9,15 m after end of training/onset of independent walking 3 steps | |

| Cadence, 1st principle component of gait | ↑ in both groups, ↑ in HI group vs. LG | ||||

| Velocity | ↑ in both groups, group difference approached significance | ||||

| Step length, dynamic base | ↑ in both groups, NS group difference | ||||

| Double support percentage | ↓ in both groups, ↓ in HI group vs. LG | ||||

| Step width, foot rotation, asymmetry | ↓ in both groups, NS group difference | ||||

| Ulrich 200128 |

Developmental, randomized controlled trial | TT n=15 303 (53) d Control:n=15 312 (66) d Gender not reported |

Down syndrome Delayed motor development |

Every 2 wks until each skill was achieved Number of days elapsed between onset of independent sitting for 30 sec and |

|

| 1) onset of ability to raise up to stand, | ↓ in TT group vs. control group approached significance | ||||

| 2) onset of ability to walk with help, and | ↓ in TT group vs. control group, large effect size | ||||

| 3) onset of independent walking 3 steps | ↓ in TT group vs. control group, large effect size | ||||

| Ulrich 200829 |

Developmental, randomized comparison of two treatment protocols | LG: n=14 6M, 8F 10.4 (2.2) m HI: n=16, 12M, 4F 9.7 (1.6) m |

Down syndrome Delayed motor development |

Every 2 wks until onset of independent walking 3 steps | |

| 8 items from motor subscale of BSID-II | Earlier onset of 2 items in HI group vs. LG, others NS | ||||

| 1st principal component of the 8 items | HI acquired the locomotor construct earlier than LG | ||||

| Number of alternating steps/minute on treadmill, averaged over 2 m intervals | ↑ across time for both groups. ↑ rate of ↑ in HI group at last two time points, vs. LG | ||||

| Wu 200730 | Developmental, randomized comparison of two treatment protocols and historical control group, with follow-up | LG: n=14 5M, 9F 10.4 (2.2) m HI: n=16 13M, 3F 9.7 (1.6) m Control:n=15 8M, 7F 10.4 (2.2) m |

Down syndrome Delayed motor development (same sample as Ulrich 2008, control group from Ulrich 2001) |

Every 2 wks until onset of independent walking 3 steps, gait follow-up 1–3 m later | |

| Age at onset of independent walking | ↓ HI group vs. Control, NS HI vs. LG, NS LG vs. Control | ||||

| Elapsed time between study entry and onset of independent walking 3 steps | ↓ HI group vs. Control, NS HI vs. LG, NS LG vs. Control | ||||

| Stride length | ↑ HI group vs. Control, NS HI vs. LG, NS LG vs. Control | ||||

| Velocity, stride time, stance time, step width, dynamic base | NS | ||||

| Wu 200831 | Follow-up of developmental, randomized comparison of two treatment protocols | LG: n=13 4M, 9F 10.5 (2.3) m HI: n=13 10M, 3F 9.5 (1.5) m |

Down syndrome Delayed motor development (subsample of Ulrich 2008) |

3,6,9,15 m after end of training/onset of independent walking 3 steps | |

| Strategy of obstacle negotiation |

↑ walk strategy, ↓ crawl strategy over time, HI and LG ↑ walk strategy, ↓ crawl strategy for HI vs. LG at 6 m |

||||

| Pre-obstacle velocity, cadence, step length | ↓ in last 3 steps, HI and LG, NS group difference | ||||

| Pre-obstacle step width | ↑ in last 3 steps, HI and LG, NS group difference | ||||

| Spinal Cord Injury | |||||

| Behrman 200032 |

Series of case reports | n=2 1M, 1F Each 20 y |

Subject 1: 12 mo post SCI, T5, ASIA A nonambulatory Subject 2: 1mo post SCI, T5, ASIA C Nonambulatory |

Subject 1: 0,17 wks, training wks 1–17 Subject 2: 0,20 wks, training wks 1–20 |

|

| ASIA Level, LEMS, | Subject 1: no change Subject 2: ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| FIM locomotion subscales | Subject 1: no change Subject 2: score unchanged, ↑ mode | ||||

| Comfortable and fast walking velocities | Subject 1: unable Subject 2: unable pre, ↑ post | ||||

| Distance walked in 2 minutes | Subject 1: unable Subject 2: unable pre, ↑ post | ||||

| Behrman 200833 |

Case report | n=1 1M 4.5 y |

16 mo post SCI ASIA C C8 bilaterally Nonambulatory |

0,16 wks, training during wks 1–16 | |

| ASIA Level, Ashworth, clonus, Babinski, | No change | ||||

| LEMS | Score unchanged, ↑ at hip flexors, ↓ at ankle plantarflexors | ||||

| WISCI-II, standing and walking ability | ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| Self selected and fast walking velocities | ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| StepWatch activity monitor (2-day period) | ↑ post vs. pre | ||||

| Range of motion at hip, knee, ankle | No change | ||||

| Dietz 1998a34 & Dietz 1998b35 |

Case series | n=2 2M 13, 14 y |

SCI Subject 1: C6, ASIA D Subject 2: C5, ASIA C |

Weekly gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior electromyography during treadmill gait | ↑ stance phase gastrocnemius activity and ↑ swing phase tibialis anterior activity with training |

| 0,1,2,3,6 m post trauma, somatosensory and motor evoked potentials | No change | ||||

| Hornby 200536 |

Case report | n=1 1F 13 y |

6 wks post SCI, C6 ASIA C Nonambulatory |

0,8,20 wks, training during wks 1–20 | |

| LEMS, WISCI-II | ↑ during each interval | ||||

| FIM locomotor subscore (over ground) | ↑ during each interval | ||||

| 10m Walk Test, 6min Walk Test | Unable pre, ↑ during each interval | ||||

| Functional Reach Test in sitting | Unable pre, ↑ after 8 wks, maintained at 20 wks | ||||

| Functional Reach Test in standing | Unable pre, ↑ during each interval | ||||

| Prosser 200737 |

Case report | n=1 1F 5.8 y |

1 mo post SCI, C4, and mild TBI ASIA C |

0,1,6 mo, training during mo 2–6 | |

| UEMS, LEMS, | ↑ during each interval | ||||

| Pin prick and light touch sensory scores | ↑ at 6 mo vs. 0 mo | ||||

| WeeFIM mobility, self-care, WISCI-II | ↑ at 6 mo vs. 1 mo, unchanged between 0 and 1 mo | ||||

| Parent reports of participation | ↑ walking participation in school, church and community | ||||

Bold type indicates statistically significant results, NS = non-significant, ↓ = decrease or less, ↑ = increase or greater, CP = cerebral palsy, TBI = traumatic brain injury, SCI = spinal cord injury, IVH = intraventricular hemorrhage, BPD = bronchopulmonary dysplasia, GMFCS = Gross Motor Function Classification Scale, FAC = Functional Ambulation Category, GMFM = Gross Motor Function Measure, PEDI = Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory, AIMS = Alberta Infant Motor Scale, BSID-II = Bayley Scales of Infant Development, 2nd edition, FIM = Functional Independence Measure, WeeFIM = Functional Independence Measure for Children, SWAPS = Supported Walker Ambulation Performance Scale, ASIA = American Spinal Injury Association, LEMS = Lower Extremity Motor Score, UEMS = Upper Extremity Motor Score, WISCI-II = Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury II, MAS = modified Ashworth scale, fMRI = functional magnetic resonance imaging, S1M1 = primary sensorimotor foot area, SMA = supplemental motor area, Cing = cingulate motor area, SII = secondary somatosensory area, TT = treadmill training, NMES = neuromuscular electrical stimulation, KAFO = knee ankle foot orthosis, ABA, AB and BA indicate experimental designs in which B represents an intervention phase and A represents a baseline or follow-up phase, HI = higher intensity, individualized, LG = lower intensity, generalized, m = month or meter, wk = week, d = days, y = years, min = minute, sec = second, M = male, F = female, CA = corrected age, LE = lower extremity

Table 2.

Description of Locomotor Training Methods by study

| First Author, Year | Setting | Type of training | Program frequency and duration | Treadmill walking time | Speed | BWS | # of people providing physical assistance | Co-interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral Palsy/Other Central Motor Impairments | ||||||||

| Begnoche 20079 | OP | BWSTT | 4 d/wk, 4 wks (1 subject 3d/wk) | 5–20 → 5–32 min | 18–54 → 22–63 cm/s | Amount not reported Based on gait pattern |

1 | Traditional PT 85–105 min/d, 4 d/wk, (1 subject 3 d/wk) |

| Blundell 200310 | School | Treadmill walking | 2 d/wk, 4 wks | not reported | not reported | 0 | 0 | Stretching, work stations for strength, segmental control, balance, 2 d/wk |

| Bodkin 200311 | OP/home | Treadmill stepping | 3d/wk, 23 wks | 4 min 40 sec | 15 cm/s | Amount not reported Supported over treadmill by PT or parent |

1 | PT, 2d/wk |

| Borggraefe 200812 | OP | BWSTT with Lokomat DGO | 4d/wk, 3 wks | 24–43 min | 31 → 50 cm/s | 50% BW→ almost 0 Based on gait pattern |

0 | PT 1–2x/wk, botulinum toxin A, 2 months prior |

| Cernak 200813 | OP/home | BWSTT, over ground gait training | 5 d/wk, 4 wks, 1 mo. break, then 5 d/wk, 4 mo | 15 min on treadmill, 5 → 15–20 min over ground | 18 → 54 cm/s | 30 → 10% BW Based on upright posture and independent stepping |

3 → 1 | In-home PT 90 min/d, 2 d/wk |

| Chan 200414 | OP | Treadmill walking | 3d/wk, 4 wks | 15 min | 45–80 cm/s | 0 | 0 | Usual conventional PT One group also received NMES to plantarflexors |

| Cherng 200715 | OP | BWSTT | 2–3d/wk, 12wks | 20 min | Individualized, gradually increased | Amount not reported Based on gait pattern |

1 | Regular therapeutic treatment based on NDT, 30 min/d, 2–3d/wk |

| Day 200416 | OP | BWSTT, standing, weight shifting with PBWS | 2–3d/wk, 25 wks, one 3wk break, one 1wk break | 19–31 min standing 11–25 min stepping |

9–36 → 58 cm/s | 40–60%BW | Up to 3 | Stretching 2–3 d/wk, Continuation of regular PT 2x/wk, OT 1x/wk, and Baclofen pump |

| DeBode 200717 | OP | BWSTT, over ground gait training | 2 x/day, 5 d/wk, 2 wks | 25 min on treadmill, 30 min over ground | 80–220 → 130–380 cm/s | 0–30 %BW, Based on gait pattern | 1 | Stretching 2x/d, 5d/wk Recommended additional walking 1 hr/d. 7 took antiepilepsy medications. |

| Dodd 200718 | School | BWSTT | 2d/wk, 6 wks | 10.3–19.0 →18.2–30.0 min | 8–17 → 11–31 cm/s | Amount not reported Based on standing posture |

0–1 | Continued with physical activity programs and PT |

| Lotan 200419 | School | Treadmill walking | 36–50 sessions, 2 mo | 5 → 30 min | Individualized | 0 | 1 | None noted |

| Meyer-Heim 200720 | IP/OP | BWSTT with Lokomat DGO | IP group: 13–21 sessions, OP group: 10–13 sessions # of wks not reported |

IP: 16–28 min OP: 23–32 min |

IP: 28–75 cm/s OP: 42–58 cm/s |

50% BW initially, decreased based on stance posture IP: 18–56 %BW OP: 0–30 %BW |

0 | IP: IP rehab program with PT 2–5 d/wk, 5 had recent ortho/neuro surgery. OP: 8 had recent Botox injections. |

| Phillips 200721, Provost 200722 | OP | BWSTT | 2x/day, 6 d/wk, 2 wks | 30 min | 67–86 → 103–139 cm/s | 30 → 0 %BW | 3 | None noted |

| Richards 199723 | OP | BWSTT | 4d/wk, 4 mo | ~10–15 hrs total | 7 cm/s initially, increased 2 of 4 subjects achieved 70 cm/s | Amount not reported, decreased over time, 2 of 4 subjects achieved 0% BWS | # not reported, decreased over time | PT 4d/wk, 31.3–40.2 hrs total, based on NDT, emphasis on active functional movements |

| Schindl 200024 | OP | BWSTT | 3d/wk, 12 wks | 10.0–19.2 → 12.3–25.0 min | 14–42 → 25–47 cm/s | 0–40 %BW, Based on gait pattern | 2 initially, decreased over time | PT 30 min, 2–3x/wk, medications kept constant |

| Seif Naraghi 199925 | OP | BWSTT | 22 sessions, 4 mo | 10 min 35 sec → 40 min | 31 → 63 cm/s | 30 %BW, Based on gait pattern | 3 → 1 | None noted |

| Down Syndrome | ||||||||

| Angulo-Barroso 2008a & 2008b, Ulrich 2008, Wu 2007, Wu 200826, 27, 29–31 | Home | Treadmill stepping | 5 d/wk until walking onset | LG: 6–7 min HI: 6 → 9 min |

LG: 18 cm/s HI: 18 → 22 cm/s |

Amount not reported Supported over treadmill by parent |

1 | Regular PT |

| Ulrich 200128 | Home | Treadmill stepping | 5 d/wk until walking onset | 8 min | 20 cm/s | Amount not reported Supported over treadmill by parent |

1 | Biweekly PT with home program, other early intervention services |

| Spinal Cord Injury | ||||||||

| Behrman 200032 | OP | BWSTT, also over ground gait training for subject 2 | Subject 1: 5d/wk, 17 wks Subject 2: 3d/wk, 20 wks |

Up to 30 min | 75–125 cm/s | Based on gait pattern Initial amount not reported. 0–10% at end of training |

3 initially, decreased over time | Subject 1: None noted Subject 2: Post-injury recovery, IP rehab program |

| Behrman 200833 | OP | BWSTT, over ground gait training | 5d/wk, 16 wks | 20–30 min treadmill, 10–20 min over ground | 30–60 → 120 cm/s | 40–50 → 15–20 %BW | at least 3 → 1 | None noted |

| Dietz 1998a34, Dietz 1998b35 | IP | BWSTT | 1x/d, 12 wks | not reported | 42 cm/s | Up to 80% BW | 2 | Post-injury recovery, IP rehab program, Clonazepam, Baclofen |

| Hornby 200536 | IP/OP | BWSTT, with Lokomat DGO for first 8 wks | 3d/wk, 20 wks | 21–30 min | Wks 1–8: 56 cm/s Wks 9–20: 56 → 111 cm/s |

Wks 1–8: 75%BW Wks 9–20: 43 → 15 %BW Based on gait pattern |

Wks 1–8: 0 Wks 9–20: 1 → 0 |

Post-injury recovery, baclofen/tizanidine, Wks 1–12: IP PT/OT 3–5 hrs/wk, Wks 13–20: OP PT/OT 6x/wk |

| Prosser 200737 | IP | BWSTT, over ground gait training | 3–4 d/wk, 5 mo, one 1 wk break | 10 min for sessions 1–3, 20 min for remainder | 27 → 98–112 cm/s | 80% → 10%, Based on gait pattern |

2 → 1 | Post-injury recovery, IP rehab program, Halo brace, collar |

OP = outpatient, IP = inpatient, BWSTT = body weight support treadmill training, DGO = driven gait orthosis, PT = physical therapist or physical therapy, NMES = neuromuscular electrical stimulation, NDT = Neuro-Developmental Treatment, LG = lower intensity, generalized, HI = higher intensity, individualized, x = times or sessions, d = days, wk = week, mo = months, min = minutes, sec = seconds, cm/s = centimeters per second (all speed values have been converted to cm/s), %BW = percent of body weight, → indicates progression from the beginning to the end of the training program, whereas values separated by a dash indicate a range of values reported.

Table 3.

Sackett’s Levels of Evidence38

| Level | Intervention Studies |

|---|---|

| I | Systematic Review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) Large RCT with narrow confidence interval (n>100) |

| II | Smaller RCTs (n<100) Systematic Reviews of cohort studies Very large ecological studies |

| III | Cohort studies (must have concurrent control group) Systematic Reviews of Case Control Studies |

| IV | Case series Cohort Studies without concurrent control groups Case-Control Study |

| V | Expert opinion Case study Bench research Expert opinion based on theory or physiological research Common sense anecdotes |

Table 5.

Level and quality of evidence supporting treadmill and/or body weight supported gait training

| Sackett Level of Evidence | PEDro Item Scoring | PEDro Total Score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |||

| CP/Other Central Motor Impairments | |||||||||||||

| Begnoche 20079 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||

| Blundell 200310 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||

| Bodkin 200311 | V | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Borggraefe 200812 | V | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Cernak 200813 | V | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Chan 200414 | II | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Cheng 200715 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Day 200416 | V | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Debode 200717 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Dodd 200718 | III | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Lotan 200419 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Meyer Heim 200720 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Phillips 200721 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Provost 200722 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Richards 199723 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Schindl 200024 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Seif-Naraghi 199925 | V | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Down Syndrome | |||||||||||||

| Angulo-Barroso 2008a26 | II | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||

| Angulo-Barroso 2008b27 | II | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Ulrich 200128 | II | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Ulrich 200829 | II | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Wu 200730 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Wu 200831 | II | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Spinal Cord Injury | |||||||||||||

| Behrman 200032 | IV | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Behrman 200833 | V | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Dietz 1998a34 | IV | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Dietz 1998b35 | IV | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Hornby 200536 | IV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Prosser 200737 | V | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

Table 4.

PEDro Scale (Physiotherapy Evidence Database)8

| Item # | Criteria (Yes = 1 point) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Eligibility criteria specified |

| 2 | Subjects randomly allocated to interventions or order of treatment |

| 3 | Concealed allocation |

| 4 | Groups similar at baseline |

| 5 | Blinding of subjects |

| 6 | Blinding of those who provided intervention |

| 7 | Blinding of assessors for at least one key outcome |

| 8 | Measure of one key outcome obtained from >85% initial subjects |

| 9 | All subjects who had outcome measures received allocated intervention. If not, data for one key outcome analyzed by “intention to treat” |

| 10 | Between intervention group statistical comparison for at least one key outcome |

| 11 | Point measures and measures of variability provided for at least one key outcome |

| TOTAL | Sum of scores for items 2–11 |

Outcome Summary Tables 6a–c are provided based on those recommended in the AACPDM methodology document contained on their website and key outcomes across are studies are listed under the sub-categories of Body Structures and Functions or Activity and Participation as delineated in the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) recently published by the World Health Organization39 These are divided into three separate tables based on the subject population grouping. Although the primary goal of two of the studies was to demonstrate whether the training protocol could be feasibly implemented in the target population, motor-related outcome data were reported for all participants, and were included here. Table 6a includes all 17 studies on children who have, or are at risk for, a motor disability as a result of a various central motor impairments. The majority of the 114 total participants (>76%) had cerebral palsy, but there was also a small cohort of children who underwent hemispherectomies for intractable seizures17, an infant who had sustained an intra-ventricular hemorrhage11, several young girls with Rett Syndrome19, a young woman with cerebellar ataxia13 and a young man with a traumatic brain injury25. Table 6b includes the results of all currently published outcomes data collected by a single laboratory, reporting on results from two separate comprehensive home-based treadmill training protocols involving 60 infants with Down syndrome, 45 of whom participated in a treadmill intervention. Both protocols were randomized controlled trials, the first of which examined the effects of treadmill training in a group of infants with Down syndrome compared to a similar control group not receiving the training; and the second of which compared the previous training paradigm to a more intense and progressive one in terms of speed, time and additional limb loading while on the treadmill. The six different published reports each address a different set of primary or secondary outcomes that were collected before, during, and immediately after training, and/or up to fifteen months after the intervention was discontinued (as determined by the onset of independent walking by each infant participant). Table 6c includes all data on seven total participants with SCI who were less than 21 years of age, each identified as a participant from among six published case series or reports in this population, some of which also contained data on adults that was not included here.32,34–36

Table 6a.

Cerebral palsy and other central motor impairments

| Outcome by ICF Category | Results favoring BWSTT only | Results favoring BWSTT+ other | Anecdotal results favoring BWSTT | Results indicating no change or inconclusive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Structure& Function | ||||

| Cadence | IV10,15, V23 | |||

| Stride/step length | IV9,10,15 | V23 | ||

| % double support | IV15 | |||

| Base of support | IV9 | |||

| Single limb stance | V25 | IV17 | ||

| 10 Min Walk (distance) | III18 | IV22 | ||

| 6 Min Walk Test | IV20(IP) | V12 | IV21&22, 20(OP) | |

| 2 Min walk Test | IV10 | |||

| EEI (no steady state) | IV22 | |||

| Muscle Tone | V12 | IV15 | ||

| Selective Motor Control | IV15 | |||

| Treadmill speed | V25 | |||

| Treadmill time/d | V25 | |||

| Muscle Strength | IV10 | IV10 | ||

| Sit-to-Stand | IV10 | |||

| Min Chair Height | IV10 | |||

| Lateral step Test | IV10 | |||

| # treadmill steps | V11,13 | |||

| Step pattern | V11 | |||

| Over ground distance | V12 | |||

| Over ground assistance | V12 | |||

| Gait pattern | IV17 | |||

| Ankle Moment Quotient | II14 | |||

| Ankle Power Quotient | II14 | |||

| fMRI - # Voxels | IV17 | V21 | ||

| fMRI – Activation w/in Voxel | IV17 | V21 | ||

| Heart Rate at rest | IV19 | |||

| Heart Rate with activity | IV19 | |||

| Knee walking | IV19 | |||

| Up/down stairs | IV19 | |||

| Activity & Participation | ||||

| 10 m Walk Test | IV21&22 | IV10,20,, III18 | IV9, V12 | IV9 |

| Free velocity | IV10,15,17, V23 | |||

| Fast velocity | IV19 | IV17, III18 | ||

| GMFM A | V16,23 | IV15 | ||

| GMFM B | V16,23 | IV15 | ||

| GMFM C | V16,23 | IV15 | ||

| GMFM D | II14* | II14*, IV15,20(IP), IV24 | V12,16,23 | IV9,20(OP) |

| GMFM E | II14* | II14*, IV15,20, IV24 | IV9,, V12,16,23 | IV9, 21&22 |

| GMFM Total | IV15 | IV9, V16,23 | IV9 | |

| PEDI – mobility | V16 | IV9 | ||

| PEDI – self care | V16 | |||

| Gait progression | V11,15,25 | |||

| AIMS | V11 | |||

| GMFCS Level | V12 | |||

| Gillette FAQ | V13 | |||

| WeeFIM transfers | V12 | |||

| WeeFIM mobility | V12 | |||

| Fugl-Meyer | IV17 | |||

| FAC Category | IV20(IP), IV24 | IV20(OP) | ||

| SWAPS | V23 | |||

| Therapist/patient reported | V16,25 | |||

| increase in participation | ||||

Roman numerals indicate Sackett Levels of Evidence, BWSTT = Body weight support treadmill training, IP = Inpatient, OP = Outpatient, Refer to caption under Table 1 for additional abbreviations.

both groups did treadmill training

Table 6c.

Spinal Cord Injury

| Outcome by ICF Category | Anecdotal results favoring BWSTT only | Anecdotal results favoring treadmill + other training | Results indicating no change after training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Structure& Function | |||

| 6 Min Walk Test | IV36(P1) | ||

| 2 Min Walk Test | IV33(C2) | ||

| ASIA Grade | IV33(C2), V37 | IV33(C1) | |

| ASIA Sensory | V37 | ||

| ASIA UEMS | V37 | ||

| ASIA LEMS | IV33(C2), IV36(P1), V37 | IV33(C1), V32 | |

| Functional Reach | IV36(P1) | ||

| Gastrocnemius EMG Slope | IV34,35(C7) | IV34,35(C6) | |

| No. of treadmill steps | IV33(C1,C2), V32 | ||

| Amount BWS | IV33(C1,C2) | ||

| Activity & Participation | |||

| Gait velocity – free speed | IV33(C2), V32 | ||

| 10 m Walk Test | IV36(P1) | ||

| Gait velocity – fast speed | IV33(C2) | ||

| WISCI II | V32, IV36(P1), V37 | ||

| WeeFIM II – mobility | V37 | ||

| WeeFIM – self care | V37 | IV33(C1) | |

| FIM – mobility | IV33(C2), IV36(P1) | IV33(C1) | |

| FIM - stairs | IV33(C2) | ||

| Number of steps/day | V32 | ||

| Family//Patient Report | V32, V37 | ||

Roman numerals indicate Sackett Levels of Evidence, numbers in parentheses indicate the patient number or case number corresponding to the reported outcome, BWSTT = body weight support treadmill training, Refer to caption under Table 1 for additional abbreviations.

Table 6b.

Down Syndrome

| Outcome by ICF Category | Results favoring training vs. control | Results favoring HI vs. LG | Results indicating no group difference | Results favoring control or LG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Structure& Function | ||||

| Step frequency (cadence) | II27 | |||

| Stride or step length | IV30 | |||

| % Double support or stance time | II27 | IV30 | ||

| Dynamic Base or step width | II27 | IV30 | ||

| Stride time | IV30 | |||

| Foot Rotation asymmetry | II27 | |||

| Mature gait construct | IV30 | II27, II28 | ||

| Step pattern | II28 | |||

| Step number | II28 | |||

| Duration Low Activity | II26 (1yr) | |||

| Duration High Activity | II26 | |||

| Magnitude Low Activity | II26 (1yr) | |||

| Magnitude High Activity | II26 (1yr) | II26 | ||

| % walk over obstacle | II31 | |||

| % crawl over obstacle | II31 | |||

| Anticipatory adjustments. | II31 | |||

| Activity & Participation | ||||

| Walking velocity | II27, IV30 | |||

| Milestones (Bayley Motor Scale) | ||||

| 1 prewalking locomotor skills | II28 | |||

| 2 self to sit | II28 | |||

| 3 self to stand | II29, II28 | |||

| 4 cruises | II28 | |||

| 5 walks w/help | II29 | II28 | ||

| 6. stands alone | II28 | |||

| 7 walks alone | II29 | II28 | ||

| 8. walks good coordination | II28 | |||

| Age at onset walking | IV30 | |||

| Time to walking onset | IV30 | |||

Roman numerals indicate Sackett Levels of Evidence, HI = higher intensity, individualized, LG = lower intensity, generalized, For studies LG, HI, if a significant change (included interpretation of results from significant interactions)

Since the primary goal of this review was to evaluate the evidence supporting or failing to support the use of treadmill training and body weight support in pediatric therapy, this topic will be addressed first for each of the three subject groupings.

Cerebral Palsy and Other Central Nervous System Disorders

While this grouping contains the largest number of studies by far, 17 in all, no randomized clinical trial has been reported among these to evaluate the efficacy of BWSTT. The one level II study included here compares two types of treadmill training paradigms, with both groups showing significant increases in GMFM scores on the ‘Standing’ and ‘Walking, Running, Jumping’ Dimensions over time.14 Since the study did not include a ‘no treatment’ condition, however, the ability to draw conclusions is limited. The strongest research available to address intervention effectiveness is a single level III study by Dodd and colleagues18 which is a non-randomized controlled trial comparing two matched cohorts, one receiving the intervention and one serving as a control group. That study did show a significant effect for increased gait speed in the training group during a ten meter walk at the subjects’ self-selected comfortable speed. Distance walked in 10 minutes was substantially higher (by nearly 20 meters, on average) in the treatment group, but this result did not reach significance most likely because of the small group size (n=7) and the variability across subjects in the amount of change. All of the 15 other studies were Evidence Levels IV (10) and V (5) studies, with a limited number of statistically favorable effects. Some positive effects emerged from across the multiple studies, but each outcome measure that showed positive results in one or more studies also had inconclusive or equivocal results in one or more other studies. For example, changes in self-selected gait velocity and in the GMFM Dimensions D & E were the most frequently noted positive results, and they were also among the most frequently reported results that either did not show a difference or were inconclusive. Effect sizes for these three outcomes are shown in Figure 1. We used an effect size (d) of 0.20 as the lower cut-off for a small effect size, 0.50 for a medium effect size, and 0.80 for a large effect size40. As noted, while all effects were positive, none reached the cut-off for a small effect size.

Figure 1.

Effect sizes for the three most common outcomes reported in group studies within the Central Nervous System Impairment subgroup.

PEDro scores ranged from 2–6 across studies, with a median value of 2. Lower quality ratings were largely a function of the lower level study designs. A major weakness in this group of studies was the presence of co-interventions which may have had large distorting effects. In some cases, the results may have been more closely related to the other interventions than to the intervention of interest. For example, the study by Blundell and coauthors10 was primarily intended to increase strength, with treadmill training as one of many methods employed. Consequently, many of the outcome measures were assessments of functional strength and showed positive results that corroborated the isometric strength results. It is likely that the other strength training interventions had a larger effect on that outcome than the treadmill training component did. Other studies included botulinum toxin or recent surgery immediately before the intervention12,20, both of which could have potentially large positive or negative effects on outcomes depending on timing with respect to the treadmill training, muscles or joints addressed, and the aggressiveness or invasiveness of treatment. An interesting observation is that all columns in the summary table appear to show similar distributions across the ICF categories of Body Structures and Functions and Activity and Participation. This may be related to the nature of the intervention which involves training to improve a specific functional task, rather than to alleviate an impairment.

In summary, the strongest evidence, a single Level III study18, suggests that BWSTT is effective in increasing self-selected gait speed. While other positive statistically supported outcomes have been identified, any positive effects found are small and may not all be of clinical significance. The weakly positive or inconclusive outcomes from these pediatric studies are similar to those reported in other adult neurological conditions. This intervention has also not been compared sufficiently to other intervention approaches so that its relative benefits, as well as costs, cannot yet be adequately assessed. Larger studies including control and treatment comparison groups are necessary to determine efficacy foremost, and if found, whether the effort and expense associated with body weight supported treadmill training, in terms of equipment as well as therapist and patient time, are justifiable.

Down Syndrome

The study published by Ulrich and colleagues in 200128 has had a major impact on the field of infant development as well as on pediatric physical therapy since it was the first study to demonstrate that locomotor development, as measured by milestone achievement, in children with a known motor disability could be accelerated by as much as several months by practicing stepping on a treadmill while being supported by a parent for eight minutes per day. The strength of the evidence from that initial study is rated as a Level II and is strong because it was an adequately powered randomized controlled trial. Most importantly, it is the only study included in this review that demonstrates the efficacy of treadmill training in children with a motor disability compared to a control intervention. The PEDro score for that study was a 6/10, which equals the highest score assigned in this review, with points lost only because no one was blinded and allocation may not have been concealed. The second randomized trial that was done by this same group evaluated whether development could be further accelerated by increasing intensity in terms of greater treatment time, speed and resistance, showing significant group differences in achievement of two milestones. Difference in treatment effects across groups were more modest than when a treatment group was compared to a control, since both groups received treadmill training29. Interestingly, compliance with the more intense but complex protocol was not as good as with the simpler less intense protocol. Multiple secondary outcomes were measured in this second cohort and demonstrated that the more intense group showed several other beneficial short or longer term effects (up to 15 months after training ceased) including a more mature gait pattern as revealed through principal component analysis of multiple gait parameters, and through significant differences on several, but not all, measured temporal-spatial and kinematic gait parameters27. The group that received more intense training also showed more advanced obstacle avoidance strategies31 and more time spent at moderate-high activity level at 15 months post training, suggesting a possible longer term effect on levels of physical activity9. The lower intensity group showed more time spent at a low activity level, and a shorter duration of moderate-high activity, a result that appears to favor the more intense training protocol. Wu and coauthors compared the second cohort to the controls from the first cohort and demonstrated that only the higher intensity group showed greater stride length, earlier age of walking onset and less time from start of intervention until walking onset compared to controls30.

In summary, five of six studies reported in infants with Down syndrome were classified as Level II, with the one study by Wu and coauthors36 classified as Level IV since it used a control group from a previously reported study. PEDro scores ranged from 3–6. Primary outcomes from each trial tended to be at the level of Activity and Participation with respect to the ICF, while secondary outcomes were mainly at the level of Body Structures and Functions. A weakness noted in the reports resulting from the second training cohort was the fact that not all who were enrolled in that study participated in or completed the training or complied with all of the multiple types of assessments, and mean ages and standard deviations provided in the sub-studies reflected the cohort who participated in the original training protocol, rather than the sub-sample of those who had data on the secondary outcome being reported in subsequent manuscripts.

Finally, these studies support the efficacy of treadmill training for promoting the development of independent walking and for advancing other quantitative and qualitative aspects of gait performance. Some evidence further suggests that a higher intensity of training may be more effective than a less intense protocol. While group differences for several outcome measures, as shown in Tables 1 and 6b did not reach statistical significance, many demonstrated similar trends to the significant findings, and may have reached significance given a larger sample size.

Spinal Cord Injury in Children and Young Adults

In contrast to the mainly high level of evidence in infants with Down syndrome, the studies identified for those with SCI are either individual case reports or individual subject data from a multiple case series and are therefore classified as either Level IV or V, which can at best merely hint at causality. Each earned a PEDro score equal to 2. All of the studies included other types of intervention including stretching, over ground training or other non-specific physical and/or occupational therapy rehabilitation exercises. Outcomes were almost equally distributed across the ICF categories of Body Structures and Functions and Activity and Participation. Most outcome results were positive, with some showing large and clearly clinically significant changes such as progression from no ability to step, to walking independently with an assistive device by the end of training33,36,37. While many of those included showed large effects, one participant made virtually no functionally relevant changes beyond improved stepping on the treadmill32. A particularly interesting finding was the lack of change in the lower extremity motor score in a child who became a functional ambulator with a walker, showing amazingly that he could walk around his kindergarten classroom all day, but could not perform isolated knee extension33. This illustrates the task specificity of step training in this patient population. Data on children and adolescents with SCI are very limited compared to data on adults with SCI, even though it is possible that children may have greater potential for improvement, as well as a longer projected lifespan which makes aggressive rehabilitation efforts even more critically important for them. Clearly, larger more rigorous studies are needed, and given the promising preliminary evidence, are strongly warranted in this population.

Protocols

A secondary goal of this review was to evaluate whether an effective protocol emerged for specific patient groups so as to inform clinical practice. Table 2 lists the different protocols that were utilized across studies and will be summarized primarily within patient groups. In the studies with SCI that included adults, the protocol was similar for those less than 21 years of age. All of the SCI case studies or series used body weight support typically starting at a very high percentage given the level of involvement of those who underwent this type of training. The frequency cited ranged from 3 to 5 days per week. The shortest program duration was 12 weeks, and the longest was 5 months. Thirty minutes of training was a consistent upper goal across studies, with two reports failing to include this parameter34,35. Treadmill belt speeds were high with the target as normal gait speed, which is felt to be important to adequately stimulate both reciprocal stepping and arm swing32. The speed often needed to be adjusted downward to optimize the stepping pattern for each subject, which often coincided with a decrease in the amount of manual assistance needed. Some other nuances were common in this population, such as the use of specific sensory inputs provided manually by therapists particularly in the early stages of training, and the decision not to allow the use of orthotic devices or handrails.

For the infants with Down syndrome, the protocol was well defined for both treadmill training protocols that were conducted, and from which six manuscripts have been published to date. In the first protocol utilized, the designated belt speed was 20 cm/sec and the frequency was 5 sessions per week for approximately 8 minutes per session28. The other novel part of this program was the fact that it was done in the home by a trained parent who supported the infant from the front during the treadmill stepping. The second training protocol that was employed had one group training for at least 6 minutes for 5 days/week at a speed of 18 cm/sec, similar to the first protocol. The more intense group progressed over time to a slightly higher speed of 22 cm/sec and also attempted to increase the length of the sessions by several minutes29. The final modification in that group was the addition of progressively increased ankle weights, which was found on later evaluation to actually decrease stepping behavior for a period in some of the infants. The added weight increased the difficulty and caused performance to deteriorate, presumably until strength increased sufficiently27. Speed and duration for the infants were understandably much lower compared to these in studies with older participants. Given the impressive compliance in the first landmark study28, the initial protocol in particular clearly demonstrates strong feasibility as well as efficacy.

For those with central motor impairments, the protocols utilized varied tremendously. Age of participants, levels of involvement, diagnoses, and intended goals of treatment were also quite variable, so lack of consistency across protocols is not surprising. Speeds ranged from 13–380 cm/sec and the duration of sessions ranged from 4 to 43 minutes, with the majority within the range of 20–30 minutes. Nearly all sessions were conducted in therapy, although several were conducted in a school setting10,18,19, an infant case report used a home-based program similar to that used for children with Down syndrome11, and one case report transitioned a patient to a home-treadmill based on the desires and resources of the subject’s family13. Frequency ranged from 2 to 5 times per week and program duration was as short as two weeks and as long as 5 months. The amount of weight support provided ranged from none up to 60% and, in many studies or cases, was not reported. Some of these parameters were determined primarily on an individual basis, often trying to provide only as much weight support as needed to optimize the walking pattern, and increasing speed depending on each patient’s tolerance. Standardized strategies for progression were rarely provided and modifications to treatment parameters over time varied across studies and across participants within a study.

The determination of when to cease the training varied across studies as well and was related to either the predetermined program duration for the study, transition to over ground gait training when that became possible, or when the participant either met the original treatment goal or reached a plateau. For the infant studies, a natural stopping point was identified which was when the child could take steps independently and therefore practice stepping on their own. For those in whom the ambulation potential is uncertain, the stopping point is far less clear. In some of the individual case reports, treatment was continued for several weeks before the person being trained even began to take consistent steps. Some studies stopped the training when a plateau was reached13,36; however in a commentary to the more recent case report by Behrman and colleagues33, Edgerton recognizes that plateaus can be misleading, and that progress typically occurs in increments rather than a smooth linear trajectory, so a lull in progress may be just that and not a firm endpoint in recovery41. Although one case report of a child with CP made the statement that the outcomes of treadmill training improve with the length of therapy12 this logical presumption has not yet been empirically substantiated.

In summary, demonstration of efficacy of various protocols in producing clinically important changes in the level of participation for children within specific disabilities or groups of disabilities is the critical first step, as has been shown nicely in the studies of infants with Down syndrome. Systematic refinement of the various parameters for optimizing outcomes can then be the next focus assuming that treatment superiority has been demonstrated.

Adverse Effects

Only a few studies addressed adverse events during the course of the training. Schindl24 and coauthors noted that two of the ten participants in their study found the program exhausting. Meyer-Heim and colleagues27 noted that no child suffered a hip dislocation as a result, which is an important factor to consider in a patient group that is at risk for hip subluxation or dislocation. Dodd and colleagues18 reported that there were no falls, injuries, or soreness in the training group. In a study using robotic assistance in a child with CP12, it was stated explicitly that no complaints or adverse effects were reported. Richards and colleagues23 further reported that there were no adverse events and no increase in scissoring behaviors during their feasibility study. In the first study of infants with Down syndrome, Ulrich and colleagues28 noted that none of the seven infants in their study who had surgically corrected congenital heart defects demonstrated any observable problems during treadmill training28. In a case report of a child with SCI, Prosser reported that there were no episodes of autonomic dysreflexia throughout the study duration37. In summary, reports on adverse events consistently found that none of the possible risks that were anticipated and monitored were found to have occurred, pointing to the safety of these programs for children.

Discussion

It has been recognized in recent years that rehabilitation strategies have not been intense or aggressive enough as seen from the positive functional results of implementing strength training programs in persons with chronic motor disorders such as SCI, stroke, CP and TBI who had long since reached a functional plateau and/or had been discharged from therapy42. Increasing the amount and intensity of physical activity is critically important for general health and for participation of those with motor disabilities43. Those who have the greatest limitations also face the greatest challenges in accomplishing this, as well as the greatest need. Therefore, body weight support systems or devices that expand the utilization of treadmills across many rehabilitation populations and increase the feasibility of gait training even for those who are non-ambulatory have been enthusiastically endorsed by the physical therapy field. While statistical and anecdotal positive results have been reported, the level of evidence to support BWSTT in pediatric practice is generally weak or inconclusive even for answering the most basic questions of effectiveness. Task-specific gait training has been shown to be effective in adults with stroke and SCI for improving gait speed; however, the superiority of body weight supported treadmill training over other gait training methods has also not been well-established in the adult rehabilitation literature4,5, and must be established to justify its use. Even for infants with Down syndrome in whom treadmill training has been shown to be efficacious, this intervention has not yet been compared to other possible methods of stepping practice or other intense training regimens which may offer similar benefits. Larger controlled trials to address these important unanswered questions are critically needed.

A common limitation in many studies, particularly in the group with CP and other central motor disorders, is that the goal of the training often was not stated explicitly or precisely. From the standpoint of motor control, the role of the motorized treadmill is to provide repetitive task-specific practice of walking. However, treadmill training protocols can be adapted to accomplish several different goals from the level of impairment to participation, as well summarized in the introduction to the case report by Cernak and colleagues13. For example, progressively decreasing body weight support in a non-ambulatory patient can be an effective way to increase lower extremity strength, with the additional benefit of this being accomplished in a task-specific manner which should translate more readily to functional gains. In cases where the goal may be simply to increase gait speed, the protocol can be optimized to meet that goal through progressive increases in belt speed, with or without adjustments in weight support. Session duration can be progressively increased to increase endurance and fitness levels, although increases in speed and weight bearing can also help to accomplish that goal. Improving symmetry of gait patterns is important for those with unilateral or markedly asymmetrical involvement, and again may require different, specific parameter adjustments to optimally achieve that goal.

The primary goal for utilizing weight-supported treadmill training in people with SCI has been to improve stepping performance through accessing and training the spinal locomotor circuits2, but additional benefits in persons with incomplete injuries such as improvements in strength may also be secondarily achieved and contribute positively to the ultimate outcome. The extent to which the spinal pathways are secondarily affected in CP and if so, whether spinal circuits can be similarly accessed to improve motor coordination in conditions such as cerebral palsy, are fascinating and as yet unanswered questions.

In contrast to physical therapy for adults where the goal is to restore walking, the goal for infants and young children with developmental delays or disorders is often to promote the development of walking. Based on dynamical systems theory, Thelen and colleagues44 proposed that one of the major reasons why infants who had been able to take supported steps stopped stepping for a brief period in their development was the biomechanical fact that their rapid increases in growth outpaced the development of their lower extremity extensor strength. Clever experimental manipulations and training studies supported this hypothesis44,45. Motor experience that includes repetitive limb loading or trunk and lower extremity strengthening can and does provide the stimulus for developing sufficient strength to walk, suggesting that development of walking skills could potentially be augmented through training both in normal infants and those at risk for developmental delays in achieving motor milestones46. Demonstration of the efficacy of treadmill training to alter developmental trajectories, and the suggestion of longer term benefits on activity levels, has major implications for early intervention therapy practices for children with multiple disabilities, and further research in this area that tracks both short and long term effects is strongly warranted.

Finally, other issues must be more thoroughly investigated. The safety of using a treadmill over longer periods for those who are at risk for joint deformity in the short term such as fracture and hip dislocation, or at risk for osteoarthritis in young adulthood, must be more systematically and carefully evaluated. The use of other lower extremity reciprocal exercise devices such as cycles, water-based treadmills or elliptical trainers may offer similar benefits with less repetitive joint stress and should also be explored. The cost of treadmill training programs are high and this may dramatically limit their availability or duration, unless adequately justified to, and accepted by, third party payors. Perhaps finding ways to transition locomotor training to a home or community based setting as early as possible in the rehabilitation process may decrease the expense, increase access and compliance, and promote lifelong attention to physical activity, rather than providing only a short term intervention.

Conclusion

The state of the evidence for body weight supported treadmill training in pediatric rehabilitation varies across populations. Efficacy of this training compared to controls has been demonstrated in infants with Down syndrome. While some individual results can be compelling, evidence in pediatric SCI is very limited in the number of studies and the strength and quality of the evidence, so no general conclusion can yet be made regarding efficacy or effectiveness in this population. Despite the increased number of studies in CP and other central motor disorders, the strength of the evidence is generally weak with no randomized clinical trial performed to date to address the efficacy of this intervention. Optimal protocol development is still in its infancy for all three populations.

Acknowledgments

Ms. DeJong was supported in part by NIH T32HD007434 and by a scholarship from the Foundation for Physical Therapy, Inc.

References

- 1.Barbeau H, Rossingnol S. Recovery of locomotion after chronic spinalization in the adult cat. Brain Res. 1987;412:84–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]