Abstract

We present a method for supervised, automatic and reliable classification of healthy controls, patients with bipolar disorder and patients with schizophrenia using brain imaging data. The method uses four supervised classification learning machines trained with a stochastic gradient learning rule based on the minimization of Kullback-Leibler divergence and an optimal model complexity search through posterior probability estimation. Prior to classification, given the high dimensionality of functional magnetic resonance imaging data, a dimension reduction stage comprising of two steps is performed: first, a one sample univariate t-test mean difference Tscore approach is used to reduce the number of significant discriminative functional activated voxels, and then singular value decomposition (SVD) is performed to further reduce the dimension of the input patterns to a number comparable to the limited number of subjects available for each of the three classes. Experimental results using functional brain imaging (fMRI) data include receiver operation characteristic (ROC) curves for the 3-way classifier with area under curve (AUC) values around 0.82, 0.89, and 0.90 for healthy control versus non-healthy, bipolar disorder versus non-bipolar and schizophrenia patients versus non-schizophrenia, binary problems respectively. The average 3-way correct classification rate is in the range of 70 − 72%, for the test set, remaining close to the estimated Bayesian optimal correct classification rate theoretical upper bound of about 80%, estimated from the performance of the 1-nearest neighbor classifier over the same data.

Keywords: classification, default mode network, functional magnetic resonance imaging, learning machine, model selection, receiver operation characteristics, schizophrenia, temporal lobe

I. Introduction

Given the limited accepted capability of genetics to diagnose schizophrenia [1]–[3], functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is gaining importance and becoming a more widely used innocuous technique with the potential to help diagnose schizophrenic patients, among other neurological illnesses. There is great potential in the development of methods based on fMRI as a biologically based aid for medical diagnosis, given that current diagnoses are based upon imprecise and time consuming subjective symptom assessment. In this work, we propose a machine learning method, to discriminate among three input classes, healthy controls (class 1, HC), bipolar disorder (class 2, BI) and schizophrenia patients (class 3, SC) using fMRI data collected while subjects are performing two runs of an auditory oddball task (AOD), a scanning procedure that lasted about sixteen minutes for each subject. Initial feature extraction is performed using group independent component analysis (ICA), which is a data-driven approach which extracts maps of regions that exhibit intrinsic functional connectivity (temporal coherence) [4]. Based upon previous studies, we selected two independent components on which to evaluate our approach: the default mode network (DMN) and the temporal lobe. Since our aim is to obtain the complete receiver operation characteristics (ROC), and not only a single point in the ROC curve in terms of specificity and sensitivity values, we use a pattern recognition system with soft output score values. Thus our approach is based on designing four different learning machines with effective generalization capabilities using the minimization of the cross entropy (CE) cost function (Kullback-Leibler divergence) [5], [6] with a generalized softmax perceptron (GSP) neural network (NN) [7]. We use a recently developed model selection algorithm based on the estimation of the posterior probabilities called the posterior probability model selection (PPMS), and three cross validation (CV) based exhaustive NN complexity model selection algorithms: called CV with weight decay, the Akaike's information criterion (AIC) [8], and the minimum description length (MDL),[9], [10]. Hence we present a methodology to automatically and objectively discriminate between healthy controls, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia patients. The challenges one faces in the use of fMRI for classification are twofold: first one is the high dimensionality of the input feature space, and the second one is the reduced sample set size available. For the purpose of medical classification, it is especially desirable to use probabilistic Bayesian classifiers since they can provide a probabilistic estimate of the decision certainty one is making. Special emphasis is given to the methodological part of this study, aiming to present an automatic end to end system as complete as possible that enables one to obtain discriminative results for patients and controls. Thus, we opted for four soft output learning machines that enable us to compute ROC and AUC: PPMS, CV, AIC and MDL. The same data set has been previously used in [11] comprising 25 healthy controls (originally 26 but one removed since proved to be an outlier after the SVD dimensionality reduction step), 14 bipolar disorder patients and 21 schizophrenia patients. In order to obtain good generalization over the test set, there is need for a significant dimensionality reduction. We propose a two step dimension reduction procedure based on a first group mean functional activation level difference thresholded score procedure, followed by an SVD decomposition selecting the main singular values of input data matrix similar to conventional principal components analysis procedures. There are a number of differences between this paper and [11]:

Here, a machine learning system is proposed, whereas in [11] a simple yet usually effective closest neighbor approach was used. Supervised machine learning based systems have the advantage of being fully automatic, among other advantages, and can perform incremental learning when new input samples are available for training.

In this work, soft output classifiers are proposed rather than hard output decisions used in [11]. This way, one has the advantage of being able to properly estimate the ROC curves and AUC by varying soft decision threshold. In [11], only a particular point in the ROC curve was reported, giving both specificity and sensitivity values for the 3-way full classification. Nevertheless, in [11], a hard 3-way decision was used, and the threshold was on the intensity of the difference images and thus was continuous (not hard), although as previously noted only one single point in the ROC curve was reported.

By using soft output learning machines, we are also able to estimate posterior probabilities with PPMS algorithm, and at the same time, can estimate optimal neural network size during the learning phase, by methods such as pruning, splitting and merging neurons.

PPMS has advantages over other previous model selection approaches, such as CV, and the use of information theoretical criteria, as discussed in [7]. Specifically, PPMS does not require a cross validation step, thus significantly reducing the amount of time needed for validation and also leaving a higher number of input samples available for training and testing.

Here, we report the complete 3-way classifier confusion matrices as hard output decisions, not given in [11] and from those matrices we draw a number of conclusions.

Finally, in this paper, the input samples are divided into training, validation, and testing sets, with the exception of PPMS, which only needs training and testing sets as explained above, while in [11] a leave-three-out strategy was used. It is convenient to avoid the use of the leave-three-out strategy since the number of input samples is often not sufficiently large.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: in Section II, we describe the fMRI data we use. In Section III we give an end-to-end overview of our approach for the use of fMRI data to classify participants into healthy controls, those with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, including the voxel selection procedure. In addition, in Section III, soft output probabilistic machine learning architecture and algorithms are introduced, as well as the supervised machine learning framework. In Section IV, we present both soft and hard output classification results, based on estimating the ROC curves with AUC and confusion matrices, including CCR as a particular case. Finally in Section V, we briefly discuss the results previously shown and conclude.

II. Materials

We used a real fMRI data set consisting of AOD scans collected from participants who provided written consent and were compensated for their participation. All subjects were scanned for sixteen minutes during two runs of the AOD protocol, [12]. The study of schizophrenia patients with fMRI is becoming widespread, see for instance [13] for a comprehensive review, and more recently [14], [12], among others. Participants in this study included 25 healthy controls, 14 with bipolar disorder, and 21 with schizophrenia (60 in total), using an fMRI compatible sound system (Magnacoustics) with a fiber-optic response device (Lightwave Medical, Vancouver, Canada), [11], [12]. Scans were acquired at Hartford Hospital, CT, US, with a General Electric 1.5 T scanner. Functional scans consisted in two runs of gradient-echo echo-planar scans, with TR=3 s, TE=40 ms, FOV=24 cm, matrix = 64 × 64, slice thickness = 5 mm, gap=0.5 mm, and with 29 2-dimensional slices, over an 8 min and 20 seconds period for a total of 167 scans per run.

III. Methodology

A. Preprocessing and System Overview

The input to our system are the fMRI scans over time during the AOD task for each of the 60 subjects, each subject with two scanning sessions of about 6 minutes each over the GE scanner, and the outputs are the classification of subjects in one of the three possible classes, healthy controls (HC), those with bipolar disorder (BI) or schizophrenia (SC). It is worth noting that the fMRI slices had to go through a preprocessing stage, which we summarize next. Data were preprocessed using the SPM2 software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm2/). Data were motion corrected, spatially smoothed with a 10 mm3 full width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel, spatially normalized into the standard Montreal Neurological Institute space, and then coordinates were converted to the standard space of Talairach and Tournoux. During spatial normalization, the data acquired at 3.75 × 3.75 × 5.5 mm3 were resampled to 4 mm3, resulting in 40 × 48 × 34 voxels. Dimension estimation, to determine the number of components, was performed using the minimum description length criteria (MDL), [9], [10] modified to account for spatial correlation [15]. Data from all subjects were then concatenated and this aggregate data set were reduced to 25 temporal dimensions using PCA, followed by an independent component estimation using the Infomax algorithm [16]. To gain some insight into the fMRI automatic schizophrenia classification system, in Fig. 1 we depict the system block diagram. Given that the number of subjects is rather limited (60 subjects), and since the number of manipulated variable is rather high, there is an absolute necessity to reduce the dimensionality of input data through a double data reduction step, including first an independent component analysis followed by a singular value decomposition step.

Fig. 1.

Automatic fMRI Bayesian classification system block diagram for 25 healthy controls (HC, class 1), 15 bipolar disorder (BI, class 2) and 21 schizophrenia (SC, class 3) patients. The tools used as well as the dimension of data are indicated outside the corresponding system block boxes.

B. Input Feature-Space Definition

One of the most robust functional abnormalities in schizophrenia manifests as a decrease in temporal lobe amplitude of the oddball response in event-related potential (ERP) data [13], [17], [18]. Similar findings have been shown for fMRI data as well, again particularly in temporal regions [12]. In [19], authors replicated earlier work in schizophrenia patients, showing a lack of deactivation of superior temporal regions which was independent of memory-task performance, possibly reflecting a core abnormality of the condition. More recently, discriminating schizophrenia from healthy control subjects with 94% accuracy using coherent temporal lobe fMRI activity was reported [20]. Next, we define our input feature-space based on two independent brain components, believed to play a important role in discriminating schizophrenia: the temporal lobe and the default mode network (DMN). There has been evidence showing temporal lobe volume reductions in bipolar disorder, although the findings are less consistent in schizophrenia [3]. There is also work on ERP showing decreases in P300 amplitude during the auditory oddball task in bipolar disorder. In summary, the temporal lobe brain network appears robust, identifiable, and includes brain regions which are thought to be relevant to both disorders. Default mode network regions are proposed to participate in an organized, baseline default mode of brain function that is diminished during specific goal-directed behaviors [21]. The DMN network, on the other hand, has been implicated in self referential and reflective activity including episodic memory retrieval, inner speech, mental images, emotions, and planning future events [22] and recently in the level of connectivity and activity inside the brain neural network [23]. It is proposed that the default mode is involved in attending to internal versus external stimuli and is associated with the stream of consciousness, comprising a free flow of thought while the brain is not engaged in other tasks [24]. There has been evidence implicating parietal and cingulate regions that are believed to be part of the DMN in both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia [12] recently showing differences in the default mode in patients with schizophrenia [25]. The default mode network and temporal lobe brain components, both believed to be of importance when diagnosing schizophrenia, were extracted following a group spatial ICA procedure [26], [4] with the Group ICA of fMRI Toolbox (GIFT) (http://icatb.sourceforge.net/). The mean of both AOD session scans was performed. It is worth noting that the advantages of using an ICA approach in noisy fMRI scans have been widely studied in recent years, see for instance [4] and [27]–[29]

We selected fMRI voxels by thresholding the Tscore differences of classes X and Y where X and Y included either healthy HC, bipolar BI or schizophrenia SC, classes:

| (1) |

where ηX, and ηY, are the mean and variance estimated values of fMRI functional activation levels of class portions X and Y respectively, and nX and nY the number of i.i.d. samples (voxels) of portions X and Y that are compared through a t-test for statistical significance. Thus we select fMRI volume voxels that exceeded a determined Tscore thresholding level, typically selected as Tscore = 4.

Next, we show the resulting fMRI volumes for both DMN and temporal lobe brain ICs, for the three classes. In Fig. 2, we show the thresholded independent components for the DMN and the temporal lobe components, for healthy controls, those with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, respectively, estimated using group ICA [26] in GIFT, (http://icatb.sourceforge.net/).

Fig. 2.

DMN and Temporal lobe group ICA mean spatial maps for healthy controls (HC), bipolar disorder (BI), and schizophrenia (SC) class subjects. Ordered from left to right, and top to bottom: (a) DMN HC, (b) DMN BI, (c) DMN SC, (d) Temporal HC, (e) Temporal BI, and (f) Temporal SC. Images were thresholded (Tscore = 4).

C. Input Space Dimension Reduction by Singular Value Decomposition

Under some circumstances, e.g, in ill conditioned problems, a singular value decomposition (SVD) for dimension reduction, may be more desirable than using PCA based on eigenvalues of the input data covariance matrix, , since in that case the dimension of X would always be much smaller than the dimension of the estimate of covariance matrix XT X. If this is the case, the singular values of X, λi, can be better estimated than the corresponding eigenvalues . It can be shown that the SVD of input data fMRI matrix X can be written as:

| (2) |

where in our case the number of input database subjects is 60, v is the number of active voxels after the Tscore step in (1), t-test difference thresholding procedure (typically for Tscore = 4, v = 1400, which results from concatenating the features from the DMN and Temporal Lobe independent components), U60 × 60 is usually called the hangers matrix, S60 × 60 the stretchers diagonal matrix with the singular values λi in main diagonal elements, and Vv × 60 is the so called aligners matrix. After performing this decomposition, dimension reduction can be easily computed in terms of the new orthogonal database spanned by Vv × 60 , using:

| (3) |

where d is the desired reduced output dimensionality for each input subject, Vv × d an orthogonal base matrix; This way represents now the new input data components in that new orthogonal base up to the reduced economy new desired dimensionality d after SVD, always smaller than the original v input dimension of X60 × v after applying the Tscore stage, thus in fact performing a dimension reduction.

D. Neural network architecture: Generalized Softmax Perceptron

Consider the labeled input sample set with N samples, including both input vectors and labels for supervised learning where is an observation vector and dn ∈ UL = {u0,..., uL−1 is an element in the set of possible L target classes, also called the class label dn indicating to which class the input observation sample vector xn belongs. Class-i label is an L-dimensional unit vector with components uij = δij , i.e., the Kronecker delta function, every j component is equal to 0, except the i-th component which is equal to 1.

In this paper, we use a neural architecture based on the soft-max nonlinearity, which guarantees that outputs satisfy probability constraints. In particular, output yi corresponding to class i is given by

| (4) |

where

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

for i = 1,..., L and j = 1,..., Mi, where yij is the soft output of network for subclass j in class i, yi is the class i network soft output, wij is the synaptic NN weight vector for class i and subclass j, L is the number of classes, Mi is the number of subclasses within class i, same for Mk, and x is the input sample. This network, which is called the generalized softmax perceptron (GSP) can be easily shown to be a universal probability estimator [7], in the sense that it can approximate any posterior probability map P(di|x) with arbitrary precision by increasing the number Mi of linear combiners per class [30].1. Outputs yij can be interpreted as subclass probabilities, where Mi is the number of subclasses within class i. By the term subclass, we refer to a part of a class, hence classes are composed of several subclasses whose outputs are obtained by the addition of several subclass outputs belonging to the same class.

E. Complexity Model Selection and Cost Function Regularization

In [31], it is shown that any cost function providing posterior probability estimates, called strict sense Bayesian (SSB), can be written in the form

| (7) |

where vector d includes the input sample desired hard outputs di (i.e., the class labels) belonging to the previously defined UL set, vector y includes all L class network outputs which in turn use an SSB cost function for training, where y should be the posterior class probability estimates of an input sample x to belong to each of the L output classes. At the same time, h(y) is any strictly convex function in posterior probability output space , which can be interpreted as an entropy measure. In fact, the formula comprises also a sufficient condition: any cost function in this way provides probability estimates, [31]. The selection of an SSB cost function for a particular situation is an open problem. This work is based on the CE SSB cost function, defined as follows:

| (8) |

obtained from (7) by using the definition of the Shannon entropy and the probability constraint , thus we can omit the term . This choice is justified for two main reasons: first, the − CE has shown several advantages over other SSB cost functions, such us the square error (SE) cost function [32]–[34], and second, the minimization of the CE is equivalent to maximum likelihood (ML) estimation of the posterior class probabilities, [35]. Hence, large sample type arguments can be involved for steps such as order selection.

The problem of determining the optimal network size, also known as the optimal model selection problem, is in general difficult to solve [36]. The selected architecture must find a balance between the approximation power of large networks and the usually higher generalization capabilities of small networks. One can distinguish between pruning and growing algorithms, [37], or algorithms based on adding a complexity penalty-term to the objective function, for instance: weight decay (WD) [38], or the algorithms based on information theoretic criteria such as Akaikes information criterion (AIC)2 [8], [6], and the minimum description length (MDL), [9], [10] criteria. In all the approaches, complexity is evaluated upon minimizing a total cost function Ct which is composed of two distinctive terms: an error term plus an additional complexity penalizing term,

| (9) |

where C is the standard error term or cost, e.g., the empirical risk based on SE, the CE or any SSB cost function in (7), w are the network weight vectors, and Cc is the complexity penalization term. Note that the dependency on network weights w and training sample set has been made explicit in this formula. Function Cc(w) penalizes the complexity or size of the network and depends on the model (weights w) since the input sample size will be fixed for a given input sample set . Variable λ in (9) can be understood as a regularizing parameter following Tikhonov theory, [41], which helps to weight the relative importance or of both terms.

The difference among model selection algorithms resides in the complexity penalizing term. In particular, the second term on the right hand side of (9) takes the following values for CV with weigh decay, AIC and MDL strategies, since PPMS does not need this complexity penalty term definition, [7], [42]:

| (10) |

where stands for the 2-norm, represents the dimension of parameter space spanned by NN weight vectors w, i.e., the number of neural network weights roughly speaking, and the dimension of input sample set space previously defined, , that is the number of input samples.

While, by hypothesis, the number of classes L is fixed and assumed known (L = 3 is the problem at hand) and class labels are available a priori, the number of subclasses Mi inside each class is unknown and must be estimated from samples during training. A high number of subclasses may lead to data over-fitting, a situation in which the cost averaged over the training set is small, but the cost averaged over a test set with new samples is high. In addition to the three above mentioned CV-based complexity search supervised learning algorithms, CV, AIC and MDL, we examine all possible network complexities starting from {M1, M2, M3} = {1, 1, 1} up to {4, 4, 4}, where M1 is the number of estimated subclasses in the first healthy control class (HC), M2 the number of subclasses in the second bipolar disorder class (BI), and M3 the estimated number of subclasses in the third schizophrenic class (SC). Hence for L = 3, that is a total of 64 different network complexities. Thus, we apply a recently proposed algorithm to determine the GSP optimal complexity while in the learning phase without using any CV techniques. The algorithm is called the posterior probability model selection (PPMS) algorithm, [7], and belongs to the family of growing and pruning algorithms [37]: starting from a pre-defined (random) architecture structure, subclasses are added to or removed from the network during supervised learning according to needs. PPMS determines the number of subclasses by seeking a balance between generalization capability and learning toward minimal output errors.

F. Stochastic gradient descent learning rule for GSP architecture and CE cost function

Next, we derive the gradient descent supervised learning rule for the cross entropy, cost function (8) in a GSP network architecture, which was used in obtaining all the classification results from the fMRI 3-class real database. The learning rule can be written as follows:

| (11) |

where yij is subclass ij network soft output, yi class i network soft output, di the desired hard output for class i (supervised learning class labels), L is the number of output classes in GSP network, (4), wij is the weight vector belonging to subclass j and class i, Mi is the number of subclasses within class i, x is a vector input data sample, n represents the n-th algorithm iteration and ρ is the learning rate parameter, which is initialized to ρ0 and subsequently decreased as specified in Section IV. The derivation of the updates in (11) are given in the Appendix.

IV. Results

The experiments presented were carried out using Matlab on a general purpose machine running Linux. In our problem, L = 3, that is, we have three classes: healthy controls (HC, class 1), patients with bipolar disorder (BI, class 2) and schizophrenia patients (SC, class 3). The input data fMRI voxels were selected as indicated previously, using the difference t-test Tscore = 4, (1), over the six mean difference pairwise images from the three existing classes, and for the two brain estimated group ICA independent components, DMN and temporal lobe. The SVD step is performed for dimension reduction, with an optimal number of SVD components set equal to d = 10, a value that provides a reasonable tradeoff for the input dimension of classifiers learn from the limited number of input subjects in this dataset, (3). Both the Tscore and SVD output dimension d optimal values for this database were empirically cross validated.

The simulation parameters and details follow next. We separated the input data to three disjoint groups: training set, with ne = 40 randomly chosen subjects, validation set with nval = 10 random subjects (used only for CV-based approaches, that is, CV, AIC and MDL) and test set, with ntest = 10 random subjects, where all sets are disjunct and total 60 subjects. In order to reduce effects of noise in the data and to obtain statistically meaningful results, experiments where repeated ncic = 200 times independently, and in each run, both the initial NN complexity estimate of PPMS and the NN weights of all supervised learning machines were randomly initialized as well as the members in the training, validation and test sets. Thus all ROC, AUC and confusion matrices results shown in this section comprise a total of 200 × 10 = 2000 test random samples, same samples for all 4 supervised (class labels available) learning machines over the 200 simulations repeated, randomly chosen in each simulation. The number of classes was set to L = 3, initial learning rate ρ0 = 0.995, see (11), learning rate reduction parameter with time (iteration number) τ = 25, thus implying a halving of the initial learning rate ρ0 each τ learning input patterns, number of runs to average in all 4 learning machines was set to ncic = 200. For PPMS algorithm, the three prune, split and merge thresholds were initialized as follows: μprune = 0.09, μsplit = 0.25, μmerge = 0.1 All these three thresholds were increased/decreased each time an split/prune operation took place, respectively, [7]. For cross validation based CV, AIC and MDL cases, Tikhonov regularization parameter was initially set to λ0 = 0.08, with a minimal CV-based network complexity number of subclasses of and a maximal CV-based network complexity number of subclasses of . The nval = 10 validation sample set was used to select among the CV exhaustive NN optimal complexity starting from complexity {1, 1, 1} up to {4, 4, 4}, thus running 64 repeated CV runs each time, being not that case under PPMS algorithm as previously mentioned. The average complexity for the four algorithms studied are as follows: CPPMS = {4.16, 2.43, 3.11}, CCV = {2.86, 2.03, 1.78}, CAIC = {1.60, 1.36, 1.29}, and CMDL = {1.56, 1.33, 1.28}.

A. Soft decisions: Receiver Operation Characteristic for 3-way classifiers with AUC estimates

To provide a general performance metric that yields a single specificity-sensitivity value for each binary problem, we plot and compute both the ROC curves and AUC values for each set of binary problems, where in the latter case, an optimal classifier is easily identified as one in which its AUC is the unit value. Note that no training was carried out for the 2-way classifier, hence the classifier is always a true 3-way classifier although binary ROC analysis only involves two different classes at a time. To do so, we need to have the soft output classifier scores. The way to compute the ROC is quite straightforward for the NN classifier. Once we have the soft outputs in the range {0,1} as estimates of the posterior class probabilities for each of the three classes (healthy, bipolar and schizo), we vary the output classifier decision threshold for each input sample in the test set. The decision threshold should be varied in the range {0,1} so as to move from the point (0,0) to the point (1,1) in the false positive ratio (FPR), true positive ratio (TPR) plane, (FPR, TPR), or equivalently moving from point (1,0) to point (0,1) in the (1-specificity, sensitivity) plane. Thus, in our case this is a straightforward procedure since we record also the soft classifier outputs (score) just before the winner takes all (WTA) hard decisions. This way, moving through the ROC curve in the (1-specificity, sensitivity) plane, we can report various specificity-sensitivity values of the classifiers rather than a single pair. The test set for computing the confusion matrices is the same as the one already defined, consisting of ncic = 200 independent runs after random initialization of networks weight (and initial complexity for the PPMS case) 10 randomly picked sample test sets, totaling 2000 test samples, were computed in order to obtain statistically significant results.

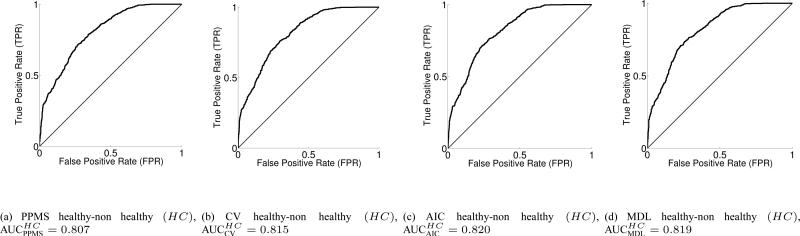

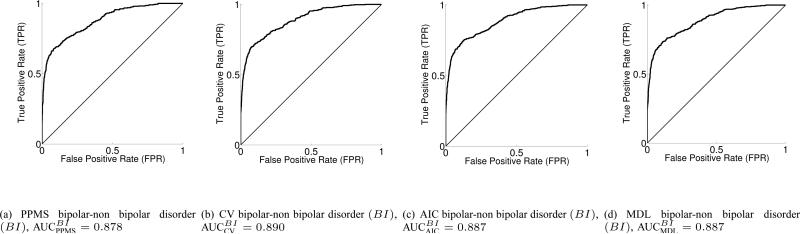

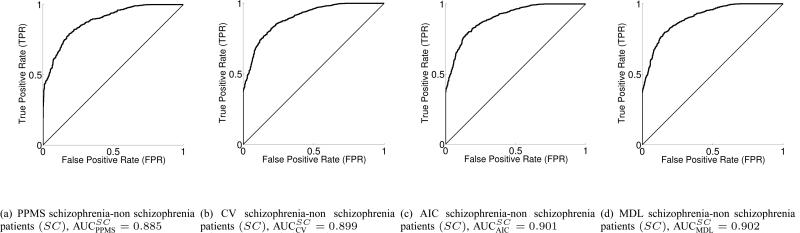

In Fig. 3, we display the healthy vs. non-healthy (class 1 vs. union of class 2 and 3) binary ROC and AUC values, for PPMS, CV, AIC and MDL, while the corresponding ROCs and AUC values for the bipolar vs. non-bipolar case are depicted in Fig. 4. The schizophrenia vs. non-schizophrenia comparison is given in Fig. 5. Taking into account both the rather simple voxel selection procedure, and the extremely high dimensionality of each input sample, together with the fact that the number of subjects in each class is rather limited, the results can be considered to be very encouraging for the discrimination task. In addition, the AUC values in test set for 200 (ncic) independent runs each with 10 test samples, totaling 2000 test samples, for each of the 3 binary classification problems HC, BI, SC and for all 4 learning machines, PPMS, CV, AIC and MDL, can be found in Table IV-A.

Fig. 3.

3-way classifier Receiver Operation Characteristics and AUC for the healthy vs. non healthy controls (HC) binary problem (test set) for ncic = 200 independent random runs with 10 samples in test set, totaling 2000 test samples.

Fig. 4.

3-way classifier Receiver Operation Characteristics and AUC for the bipolar vs. non bipolar disorder (BI) binary problem (test set) for ncic = 200 independent random runs with 10 samples in test set, totaling 2000 test samples.

Fig. 5.

3-way classifier Receiver Operation Characteristics and AUC for the schizophrenia vs. non schizophrenia patients (SC) binary problem (test set) for ncic = 200 independent random runs with 10 samples in test set, totaling 2000 test samples.

It looks clear that the greatest discriminative power is obtained in the schizophrenia vs. non-schizophrenia binary paradigm (AUCSC in the range of 0.90, Fig. 5), with some advantage over the second discriminative power in the bipolar vs. non-bipolar problem (AUCBI about 0.89, Fig. 4) and a finally the healthy vs. non-healthy case (AUCHC about 0.82 approx., Fig. 3). The ROC curves suggest that the classifiers have more trouble in either properly discriminating healthy controls and/or bipolar subjects.

The best average performance in terms of AUC values corresponds to the MDL classifier, closely followed by the AIC classifier and then followed by the CV one. The worst classifier is the PPMS although by a narrow margin, and also one has to take into account that the first three above mentioned learning schemes performed an exhaustive CV-based search for the optimal NN complexity, while PPMS finds the optimal model selection automatically while in the learning phase and from the estimates of the posterior class probabilities at output, thus being much less computationally expensive. As seen from the three binary classification tasks, the differences in the classifiers are not significant.

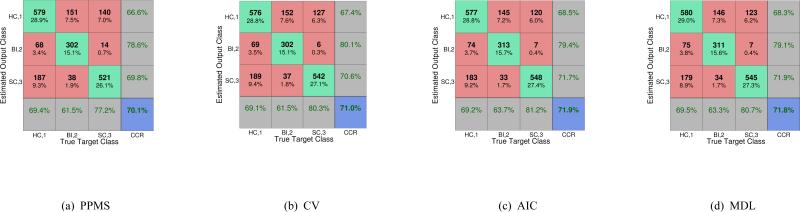

B. Hard decisions: Confusion Matrices and the Correct Classification Rate

In addition to ROC and AUC analysis shown above, we also compute the correct classification rate (CCR) for the particular classifier decision threshold obtained after training phase, over the test set. To that end, we compute the 3 × 3 confusion matrices for each of the four classifiers, PPMS, CV, AIC and MDL, which includes also the external row and column CCR as a particular case. The test set for computing the confusion matrices is the same as the one already defined, consisting of ncic = 200 independent runs after random initialization of networks weight (and initial complexity for the PPMS case) 10 randomly selected sample test sets, totaling 2000 test samples.

In Fig. 6(a), we show the confusion matrix for the PPMS algorithm over the test set, being again the worst one in average terms, but by a narrow margin. In Figs. 6(b), 6(c) and 6(d) we show the confusion matrices for the CV, AIC, and MDL algorithms, respectively, over the test set. An initial conclusion upon observing the four confusion matrices is that despite the small differences among the performance of the classifiers, there is a general tendency in the four classifiers to behave consistently, all achieving a CCR slightly above 70% in the 3-way classification, and in terms of the CCR the best performer is AIC, closely followed by MDL, then CV and finally PPMS continues to be the worst classifier though a direct comparison using the ROC curves cannot be done for the reasons already explained.

Fig. 6.

3-way classifier learning machines 3 × 3 confusion matrix including CCR, computed over 2000 test samples: (a) PPMS, (b) CV, (c) AIC and (d) MDL. The estimated class is given in rows and the true class in columns; class 1 healthy controls (HC), class 2 bipolar disorder (BI), class 3 schizophrenia (SC). ncic = 200 independent random runs with 10 samples in test set, totaling 2000 test samples.

Next, we use the 1-nearest neighbor (nn) classifier to estimate the upper bound CCR for the optimal classifier given the intrinsic entropy of input data. Let us follow equations number (4.39) and (4.52) in [43], where authors define P as the probability of classification error for the k-nearest neighbor classifier, and P* as the probability of classification error for the optimal Bayesian classifier. Given the fact that the correct classification probability (CCR/100) for the k-nearest neighbor classifier can only be estimated as 1 − P since we always have a finite number of samples in real experiments, and also given that usually the minimum error achievable by the optimal Bayesian classifier P* is small, we can omit the higher order term in the equations given in [43]. Thus, the bounds for optimal P* will be given by:

| (12) |

where nn subindex stands for the simple 1-nearest neighbor classifier, opt subindex stands for the optimal classifier, r = CCR/100 is the mean correct classification normalized to unity, thus 1 − r = (100 − CCR)/100 is the normalized classification error. For our fMRI input data, we estimate 1 − P = rnn = 0.602 so following the upper bound equation in (12) we end up with an estimate for the upper bound optimal Bayesian classifier correct classification value of 0.602 ≤ ropt = 1 − P* ≤ 0.801, thus leading to 60.2% ≤ CCRopt ≤ 80.1%. Hence we can conclude that our GSP NN based classifiers CCR results given in Section IV-B are rather close to the estimated optimal Bayesian upper bound for CCR for the data at hand.

It is also worth noting that, looking at the elements of the confusion matrix in positions (row,column) = (1,2) is particularly meaningful in relative terms, as well as (3,1), in absolute terms (taking into account the total number of input samples in each class), since a relatively high number of bipolar subjects are being classified as healthy ones, and in absolute terms a high number of healthy subjects are being classified as schizophrenic, consistently for the four classifiers. This is clearly the reason for the poor performance in the binary healthy vs. non-healthy paradigm classification results, by far the worst ones, and should be taken into account in future studies to further improve the classification accuracy. Finally, the opposite situation holds in elements (2,3) and (3,2) of the four confusion matrices, meaning that the classifiers accurately discriminate between the bipolar and schizophrenic subjects, and in relative terms also between healthy and schizophrenic subjects. The fact that the automatic classifications are accurate between bipolar and schizophrenia subjects is worth emphasizing, since it is difficult to physicians to clinically differentiate bipolar and schizophrenia as these two might have overlapping symptoms. In summary, PPMS should be preferable when low computational cost is desired, whereas MDL (or AIC) should be the one to choose especially when a high number of input samples are available.

V. Conclusions

We have proposed a machine learning based system, fully automatic and potentially able to perform incremental learning by defining three disjoint training, validation and test sets, including soft output posterior probability estimates and model complexity selection. The method allows one to provide full 3-way classification confusion matrices (CCR and errors among the three classes) from hard decisions and ROC and AUC values from soft outputs. PPMS has several advantages over its partners, such as the possibility of estimating the optimal network size while learning phase (no need to define an arbitrary Cc penalty term in the cost function). It also does not need a validation set since no cross validation phase is needed, thus it is computationally more attractive and can achieve a similar performance in terms of CCR and AUC, only slightly below those of CV, AIC, and MDL. Through the experiments proposed over the real brain imaging data, we have shown the promising generalization capabilities of the four objective and automatic learning machines to 3-way classify between healthy controls, those with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The mean AUC values were near 0.9 and CCR over 70% for 200 independent runs including 2000 test samples to reduce noise and for statistical significance purposes. CCR values are in turn close to the estimated optimal correct classification (CCRopt) upper bound of around 80% for this data for the 1-nearest neighbor classifier, over the whole test set. There is an obvious trade-off between speed and accuracy, and in addition, we have provided the guidance on selecting an optimal classifier for a given problem. Even though the differences observed among the classifiers were not significant, we note the following: PPMS is preferable for low computational cost in real-time systems, whereas either MDL or AIC should be the ones to choose particularly when a high number of input samples are available. More powerful feature selection algorithms could be also investigated to see if they provide an additional classification accuracy gain. The small number of subjects used in the study is an important limitation of the present work, and it is desirable to extend the database to include more subjects in future studies. Also, it remains an open problem to understand the reasons behind a relatively high number of errors between the healthy controls and bipolar disorder subjects, as the classifiers are able to discriminate between the bipolar and schizophrenic subjects more reliably. This last result is worth emphasizing since it is quite difficult to physicians to clinically differentiate bipolar disorder and schizophrenia subjects because of the overlapping symptoms in the two. Further investigations about the existence of a possible preferred higher discriminative either temporal lobe or DMN independent components are also worth investigating. It may be also helpful to use tools such as the Matlab Prtools toolbox (http://www.prtools.org) and to study the performance using other pattern classification approaches.

TABLE I.

3-way classifier Area Under the Receiver Operation Characteristic curves (AUC) over the test set for PPMS, CV, AIC and MDL learning machines. healthy versus non-healthy (HC), bipolar versus non-bipolar (BI) and schizophrenia versus non-schizophrenia (SC) binary problems. nCIC = 200 independent random runs with 10 samples in test set, totaling 2000 test samples.

| AUC | PPMS | CV | AIC | MDL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC vs. non-HC | 0.807 | 0.815 | 0.820 | 0.819 |

| BI vs. non-BI | 0.878 | 0.890 | 0.887 | 0.887 |

| SC vs. non-SC | 0.885 | 0.899 | 0.901 | 0.902 |

Acknowledgment

Dr. Juan I. Arribas wishes to thank Pedro Rodriguez, Univ. Maryland Baltimore County, MD, USA for the help in preprocessing the fMRI data and Dr. Xi-Lin Li, Univ. Maryland Baltimore County, MD, USA, for enlightening discussions.

Appendix

Derivation of the stochastic gradient descent learning rule for the GSP architecture and the Kullback-Leibler divergence (CE cost function)

We derive the gradient descent learning rule applied to CE, see (8), cost function in the GSP architecture. The adaptation rule is based on computing the gradient of an SSB cost function with respect to the weight vector:

| (13) |

where wij is the weight vector belonging to subclass j and class i, Mi is the number of subclasses within class i, see (4), x are input samples, n represents the n-th algorithm iteration and ρ is the learning rate parameter.

When we define the GSP nonlinearity using (4), we have

| (14) |

Using the chain rule

| (15) |

Using (6),

| (16) |

where δk−i represents Kronecker delta function, equal to 1 if and only if k = i. Therefore, replacing (16) in (15), we obtain,

| (17) |

Using (5), partial derivatives can be computed as follows,

| (18) |

Using (14), (17) and (18), (13) becomes

| (19) |

Using the CCE definition given in (8) we have

| (20) |

and, thus, the learning rule becomes:

| (21) |

where remember that di is the i-th component of input sample label vector d ∈ UL, and which is the stochastic rule for CE cost and GSP NN that was used in the learning phase. Finally, in the particular case of a GSP network with a single subclass per each class, softmax network, then previous equation becomes

| (22) |

Footnotes

A part of multinomial logit model for statisticians, which in turn are a special case of the generalized linear models introduced by McCullagh. After the soft decision we would eventually have a hard decision based on a WTA structure, so the winner class obtains an activated output set to 1, and the other classes get a deactivated output 0.

References

- 1.Pearlson GD, Barta PE, Powers RE, Menon RR, Richards SS, Aylward EH, Federman EB, Chase GA, Petty RG, Tien AY. Medial and superior temporal gyral volumes and cerebral asymmetry in schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberger DR, Egan MF, Bertolino A, Callicott JH, Mattay VS, Lipska BK, Berman KF, Goldberg TE. Prefrontal neurons and the genetics of schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50(11):825–844. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strasser HC, Lilyestrom J, Ashby ER, Honeycutt NA, Schretlen DJ, Pulver AE, Hopkins RO, Depaulo JR, Potash JB, Schweizer B, Yates KO, Kurian E, Barta PE, Pearlson GD. Hippocampal and ventricular volumes in psychotic and nonpsychotic bipolar patients compared with schizophrenia patients and community control subjects: A pilot study. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calhoun VD, Liu J, Adalı T. A review of group ICA for fMRI data and ICA for joint inference of imaging, genetic, and ERP data. NeuroImage. 2009;45(1, Supplement 1):S163–S172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seghouane AK, Bekara M. A small sample model selection criterion based on Kullback's symmetric divergence. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2004;52(12):3314–3323. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seghouane AK, Amari SI. The AIC criterion and symmetrizing the Kullback-Leibler divergence. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 2007;18(1):97–106. doi: 10.1109/TNN.2006.882813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arribas JI, Cid-Sueiro J. A model selection algorithm for a posteriori probability estimation with neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 2005 July;16(4):799–809. doi: 10.1109/TNN.2005.849826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. Annals Institute Statistical Mathematics. 1974;22:202–217. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annal of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rissanen J. A universal prior for integers and estimation by minimum description length. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics. 1983;11 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calhoun VD, Maciejewski PK, Pearlson GD, Kielh KA. Temporal lobe and default hemodynamic brain modes discriminate between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Human Brain Mapping. 2008;29:1265–1275. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiehl KA, Liddle PF. An event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study of an auditory oddball task in schizoprenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;48:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;49(1-2):1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calhoun VD, Eichele T, Pearlson GD. Functional brain networks in schizophrenia: a review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2009;3(17):1–12. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.017.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li YO, Adalı T, Calhoun VD. Estimating the number of independent components for functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Human Brain Mapping. 2007;28(11):1251–1266. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell AJ, Sejnowski TJ. An information-maximization approach to blind separation and blind deconvolution. Neural Computation. 1995;7(6):1129–1159. doi: 10.1162/neco.1995.7.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suddath R, Casanova M, Goldberg T, Daniel D, Kelsoe J, JR, Weinberger D. Temporal lobe pathology in schizophrenia: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(4):464–472. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eastwood S, Harrison P. Decreased synaptophysin in the medial temporal lobe in schizophrenia demonstrated using immunoautoradiography. Neuroscience. 1995;69(2):339–343. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00324-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friston KJ, Fletcher P, Josephs O, Holmes A, Rugg MD, Turner R. Event-related fMRI: Characterizing differential responses. NeuroImage. 1998;7(1):30–40. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calhoun VD, Kiehl KA, Liddle PF, Pearlson GD. Aberrant localization of sysnchronous hemodynamic activity in auditory cortex reliably chareacterizes schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(2):676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: A network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(1):253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Green AI, Nieto-Castanon A, LaViolette P, Wojcik J, Gabrieli JDE, Seidman LJ. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(4):1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(7):4259–4264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071043098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity AG, Pearlson GD, McKiernan K, Lloyd D, Kiehl KA, Calhoun VD. Aberrant ”Default Mode” Functional Connectivity in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):450–457. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calhoun VD, Adalı T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Human Brain Mapping. 2001;14:140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKeown MJ. Detection of concistently task-related activacions in fMRI data with hybrid independent component analysis. Neuroimage. 2000;11:24–35. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calhoun VD, Adalı T. Unmixing fMRI with independent component analysis. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine. 2006;25(5):684–694. doi: 10.1109/memb.2006.1607672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adalı T, Calhoun VD. Complex ICA of brain imaging data. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2007;24(5):136–139. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cybenko G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Mathematics of Control, Signals, and Systems. 1989;2(4):303–314. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cid-Sueiro J, Arribas JI, Urbán-Munoz S, Figueiras-Vidal AR. Cost functions to estimate a posteriori probability in multiclass problems. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 1999 May;10(3):645–656. doi: 10.1109/72.761724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amari SI. Backpropagation and stochstic gradient descent method. Neurocomputing. 1993;5:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telfer BA, Szu HH. Energy functions for minimizing misclassification error with minimum-complexity networks. Neural Networks. 1994;7(5):809–818. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wittner B, Denker J. Oz W, Yannakakis M, editors. Strategies for teaching layered neural networks classification tasks. Neural Information Processing Systems. 1988;1:850–859. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adalı T, Ni H. Partial likelihood for signal processing. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing. 2003 January;10(1):204–212. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vapnik VN. An overview of statistical learning theory. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 1999 September;10(5):988–999. doi: 10.1109/72.788640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed R. Pruning algorithms — a survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 1993 September;4(5):740–747. doi: 10.1109/72.248452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinton G. Connectionist learning procedures. Artificial Intelligence. 1989;40:185–235. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murata N, Yoshizawa S, Amari SI. Network information criterion–determining the number of hidden units for an artificial neural network model. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 1994;5(6):865–872. doi: 10.1109/72.329683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amari SI, Murata N, Muller KR, Finke M, Yang HH. Asymptotic statistical theory of overtraining and cross-validation. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 1997;8(5):985–996. doi: 10.1109/72.623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tikhonov AN. On solving incorrectly posed problems and method of regularization. Doklady Akademii Nauk. 1963;151:501–504. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anders U, Korn O. Model selection in neural networks. Neural Networks. 1999;12:309–323. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(98)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duda R, Hart P, Stork DG. Pattern Classification. J. Wiley and Sons; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]