Abstract

Objective

To describe the level of obligation conveyed by deontic terms (words such as “ should,” “may,” “must,” and “is indicated”) commonly found in clinical practice guidelines.

Design

Cross sectional electronic survey.

Setting

Researchers developed a clinical scenario and presented participants with recommendations containing 12 deontic terms and phrases.

Participants

All 1332 registrants of the 2008 annual conference of the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Main Outcome Measures

Participants indicated the level of obligation they believed guideline authors intended by using a slider mechanism ranging from “No obligation” (leftmost position recorded as 0) to “Full obligation” (rightmost position recorded as 100.)

Results

445/1332 registrants (36%) submitted the on-line survey. 254/445 (57%) reported they had experience developing clinical practice guidelines.133/445 (30%) indicated they provided healthcare. “Must” conveyed the highest level of obligation (median = 100) and least amount of variability (interquartile range = 5.) “May” (median = 37) and “may consider” (median = 33) conveyed the lowest levels of obligation. All other terms conveyed intermediate levels of obligation characterised by wide and overlapping interquartile ranges.

Conclusions

Members of the health services community believe guideline authors intend variable levels of obligation when using different deontic terms within practice recommendations. Ranking of a subset of terms by intended level of obligation is possible. Matching deontic terminology to intended recommendation strength can help standardise the use of deontic terminology by guideline developers.

Keywords: deontic, practice guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines are “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.”[1] However, problems with guideline clarity and specificity impede the incorporation of guidelines into medical practice.[2, 3] Non-adherence is common.[4, 5] Several groups have developed tools that enable guideline developers to identify potential gaps in guideline quality and implementability.[6–8] High quality guidelines make explicit the connections between evidence quality, recommendation strength, and the language used to make recommendations.

Language such as “should consider” and “is recommended” appears frequently in practice guidelines and is related to deontic logic. Deontic logic is that branch of logic that concerns notions of obligation and permission.[9] Clinicians’ perceptions of obligation to undertake recommended actions, as influenced by deontic terminology, is unknown. An understanding of how readers interpret deontic terminology would allow guideline authors to strengthen the connection between guideline language and expected adherence to guideline recommendations.

Increasingly, expectations of adherence to recommendations are communicated by systems for rating quality of evidence and grading recommendation strength.[10] Yet differences among the grading systems reveal important disagreements.[11] The GRADE system, for example, divides recommendations into two categories called “strong” and “weak,” whereas the US Preventive Services Task Forces applies five letter grades (A through D, plus an I statement) to indicate “suggestions for practice.”[12, 13] The American Academy of Pediatrics uses four categories (“strong recommendation,” “recommendation,” “option,” and “no recommendation.”)[10] In England and Wales, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence no longer assigns letter grades to its recommendations but recognises three levels of “certainty.”[14] Many organisations that develop guidelines do not employ any grading system for characterising recommendation strength.

Much attention has focused on transforming the knowledge contained in practice guidelines into computable formats.[15, 16] A major challenge is how to translate guideline recommendations into decision support tools. Without knowing how guideline authors use deontic terminology, investigators cannot reliably implement recommendations that remain faithful to the developer’s intent and purpose.

Through the use of an electronic survey, we investigated the understanding of deontic terminology by members of the health services community. Our goal was to describe the level of obligation and variation in interpretation among deontic terms. To our knowledge, the study presented here is the first attempt to examine the impact of deontic terminology on the perceived level of obligation to undertake actions recommended within clinical practice guidelines.

METHODS

Survey instrument

We compiled a list of deontic terms commonly found in guidelines by considering the English forms of the French deontic terms identified by Georg et al [17] and the most frequent deontic terms appearing in the Yale Guideline Recommendation Corpus (YGRC) using the Simple Concordance Program (v4.09 for Macintosh, Alan Reed, available from http://www.textworld.com/scp.)[18] We also searched the websites of all organisations listing more than five guidelines on the National Guideline Clearinghouse website (www.guideline.gov) for any information relating to how they apply deontic terminology.

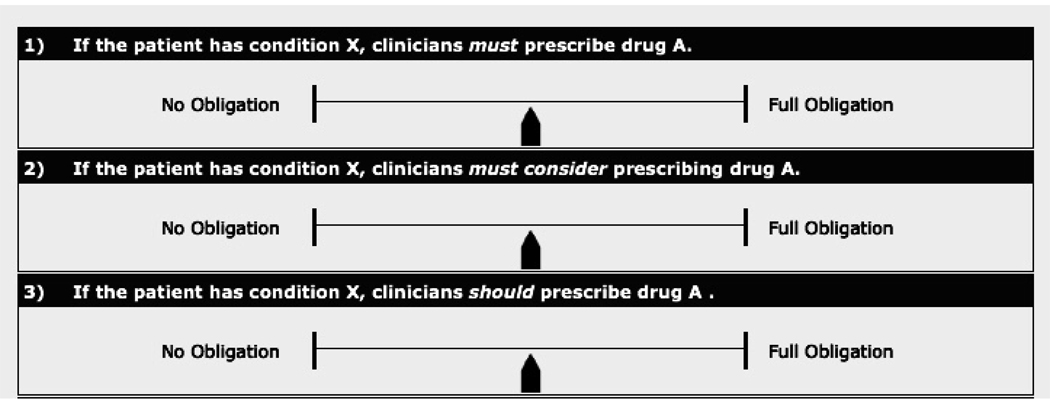

We constructed a Web-based, electronic survey that presented each of 12 deontic terms within simplified recommendation statements. To isolate the effect of the deontic term from that of any other contextual feature, we instructed participants to assume that a particular drug “A” was effective for a clinical condition “X” and presented them with recommendation statements that varied only in use of the deontic term or phrase (see figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the first three survey questions. Readers moved the slider to the left or right according to the level of obligation they believed guideline authors intended. The default position was recorded as 50 (shown above.)

Participants used a slider mechanism to record the level of obligation they believed the guideline authors intended. The scale ranged from “No obligation” (leftmost position recorded as 0) to “Full obligation” (rightmost position recorded as 100.) We gave explicit instructions that the term “No obligation” did not mean that prescribing drug “A” was prohibited; rather, selecting the leftmost position would indicate that the decision to prescribe drug “A” was completely “optional.” We also explained our understanding that clinical decisions rely heavily on individual patient circumstances and that answers about intended level of obligation may not necessarily reflect intended adherence.

We collected information about participant age, whether they provided direct healthcare to clients, and whether they had ever participated in the development of clinical practice guidelines, clinical decision support systems, or performance measures. The initial version of the survey presented each of the recommendation statements in random order to avoid the potential introduction of order bias.[19–21] Early informal piloting, however, revealed that readers could not consistently record their answers without referring to their responses from previous questions. Based on this feedback, we instituted a revised version of the survey that presented questions in non-random order and allowed participants to adjust their answers until final submission of the survey. The final version of the survey can be found at http://gem.med.yale.edu/Deontics_Survey/survey.htm.

Study population

We invited all 1332 registrants for the 2008 annual conference of the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to participate. We emailed each registrant an introductory message and a direct link to our survey website. Following a formal pilot period using 50 randomly selected registrants, the main body of the study ran for six weeks from mid October 2008 to the beginning of December 2008. We sent two reminder emails during that time. The comments we received during the pilot period did not suggest any major difficulty understanding the purpose of the study, the survey instructions, or use of the slider mechanism.

Because the survey remained unaltered following the pilot study and pilot participants were selected from the complete list of conference registrants, we combined all responses into a single analysis. We calculated a response rate based on the RR2 definition from the American Association for Public Opinion Research.[22]

Data management and analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine the variable response for each deontic term. Analysis was conducted using a standard statistical package (SPSS v16 for Macintosh.)

RESULTS

Upon registration for the AHRQ annual conference, attendees were given the option to describe themselves by choosing one or more of several professional categories (Howard Holland, AHRQ, personal communication, 2008.) Results are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of conference registrants

| Characteristic | No. | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1332 | (100) | |

| Self-described upon registration | 893 | (67) * | |

| AHRQ grantee/contractor | 135 | (15) | |

| Other federal awardee | 16 | (1.8) | |

| Researcher | 125 | (14) | |

| Healthcare provider | 120 | (13) | |

| Health plan/insurer | 17 | (1.9) | |

| Healthcare supplier or vendor | 28 | (3.1) | |

| Member of trade or professional organisation | 87 | (9.7) | |

| Healthcare purchaser | 2 | (0.2) | |

| Member of a consumer, patient, or advocacy group | 16 | (1.8) | |

| Representative of federal, state, or local government | 221 | (25) | |

| Other | 126 | (14) | |

| Survey participants | 445 | (36) † | |

| Provide healthcare | 133 | (30) | |

| Experience developing | |||

| Clinical practice guidelines | 254 | (57) | |

| Clinical decision support systems | 212 | (48) | |

| Performance measures | 314 | (71) | |

| Age ‡ | |||

| 20 – 29 | 22 | (4.9) | |

| 30 – 39 | 82 | (18) | |

| 40 – 49 | 108 | (24) | |

| 50 – 59 | 171 | (38) | |

| ≥ 60 | 57 | (13) | |

Percentages for subcategories of conference registrants use a denominator of 893.

Percentages for subcategories of survey participants use a denominator of 445.

7 participants (1.5%) did not specify their age on the survey.

445/1332 registrants submitted our on-line survey (response rate of 36%.) More than half (57%, 254/445) reported they had experience developing clinical practice guidelines, and 30% (133/445) indicated they provided healthcare (table 1.) We did not collect data from clinicians about their level of guideline usage. Respondents between 50 and 59 years represented the largest age group (38%, 171/445.)

Most organisations listing more than five guidelines on the NGC website did not provide any insight into their use of deontic terminology. Those that did provide guidance seemed to disagree on what and how terms should be used (e.g., whether the terms should be linked to specific levels of evidence quality or recommendation strength.) A partial list of organisations that commented either within published guideline manuals or directly on their websites on their use of deontic terminology is shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Deontic expressions recommended for use by a sample of guideline-developing organisations

| Deontic verb or phrase | AAN | AAPD | ACC/AHA | ACCP | NICE | NZGG | USPSTF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Should | X | X | X | ||||

| May | X | ||||||

| Must | X | ||||||

| Should be done | X | ||||||

| Consider | X | X | |||||

| Should consider | X | ||||||

| Should be considered | X | ||||||

| May/might be considered | X | X | X | ||||

| Must be considered | |||||||

| Recommend or is recommended | X | X | X | X | |||

| Is indicated | X | ||||||

| Suggest or is suggested | X | ||||||

| Is/may/might be reasonable | X | ||||||

| Is/can/may be useful | X | ||||||

| Is/can/may be effective | X | ||||||

| Offer | X | ||||||

| Discuss | X | ||||||

AAN = American Academy of Neurology[23]

AAPD = American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry[24]

ACC = American College of Cardiology[25]

AHA = American Heart Association[25]

ACCP = American College of Chest Physicians[26]

NICE = National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (England and Wales). Also provides specific instructions for the rare use of “must” and “must not.”[14]

NZGG = New Zealand Guidelines Group[27]

USPSTF = US Preventive Services Task Force[13]

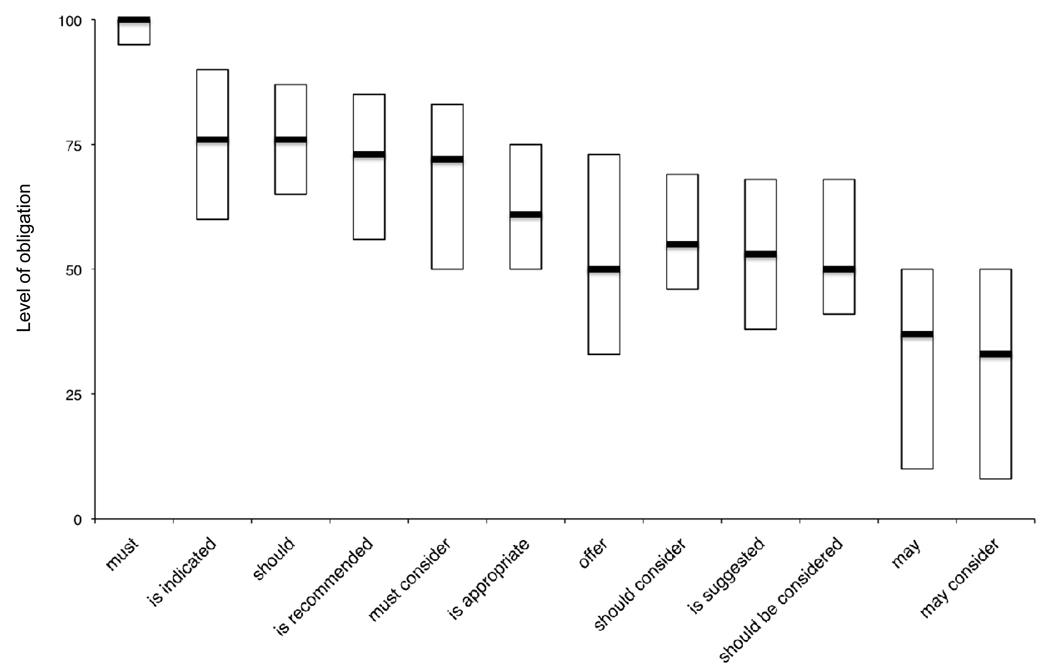

Figure 2 displays the median and interquartile range for each of the 12 deontic terms examined in our survey, arranged in descending order of perceived level of obligation. “Must” conveyed the highest level of obligation (median = 100) and least amount of variability (interquartile range = 5.) “May” (median = 37) and “may consider” (median = 33) conveyed the lowest levels of obligation. All other terms we examined conveyed intermediate levels of obligation characterised by wide and overlapping interquartile ranges (see figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Level of obligation conveyed by deontic terms commonly appearing in clinical practice guidelines. Bars represent simplified box plots displaying interquartile ranges and medians. Perceived level of obligation was recorded by a slider mechanism that ranged from 0 (“No obligation”) to 100 (“Full obligation.”)

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to describe the level of obligation imposed by deontic terms commonly found in clinical practice guidelines. We found that the interpretation of deontic terms by the health services community varies and that ranking of deontic terms by level of obligation is possible. Using an internet-based survey, we showed that “must” conveys the highest level of obligation, while “may” and “may consider” convey lower levels of obligation. “Should” and all other deontic terms we examined convey intermediate levels of obligation.

Variable interpretation of expressions used in medicine has been well documented, most notably with regard to physician interpretation of probabilities.[28–30] Kong et al demonstrated that medical professionals could agree on the ranking of common probability expressions, but there was wide variation in interpretation of each expression.[31] Similarly, our survey demonstrates a ranking of a subset of terms but considerable variability in interpretation of individual deontic expressions.

Figure 2 suggests members of the health services community recognise at least three levels of obligation. “Must” conveys the highest level of obligation, while “may” and “may consider” convey lower levels. Every other term we examined conveys an intermediate level. The addition of “consider” appears to decrease the level of obligation associated with “must” and “should” but does not change the impact of “may,” which already conveys the lowest level of obligation.

While the use of “consider” in a recommendation softens the obligation imposed, it also makes measuring performance and auditing adherence more difficult. Increasingly, performance measures are based on practice guidelines.[32] Guidelines that use “consider” pose significant challenges to quality improvement teams because it is often impossible to determine whether a recommended activity was “considered.”

A guideline reader’s formula to determine level of obligation and intended adherence likely includes a plethora of linguistic and non-linguistic variables. In addition to the deontic term encountered, a reader is likely to assess such factors as the stated recommendation strength (if present,) the type of action recommended (e.g., to prescribe a medicine vs. to order an invasive procedure or test,) the severity of the patient condition under consideration, and the organisation responsible for the guideline’s development. To our knowledge, none of these other variables have been studied as potential influences on clinicians’ perception of obligation to undertake recommended actions.

Suggestions for guideline developers

If deontic terminology were used to strengthen a connection between recommendation language and expected adherence to recommendations, these data suggest that three separate levels of recommendation strength should be available to guideline developers. As long as terms conveying distinct levels of obligation were chosen (i.e., non-overlapping interquartile ranges,) guideline developers could take advantage of a natural ranking of deontic terms.

“Must” clearly defines the highest level of obligation, but we anticipate only rare usage of the term. Based on our examination of the YGRC, “must” appears in only 19 recommendations.[18] Use of “must” or “must not” may be limited to situations where there is a clear legal standard or where quality evidence indicates the potential for imminent patient harm if a course of action is not followed. “May” is an appropriate choice for the lowest level of obligation. We suggest avoiding any expression using “consider” for reasons mentioned earlier. The impact of “not” remains a topic for future study.

“Should” is the commonest deontic verb found in the YGRC (appearing 709 times) and is an appropriate choice to convey an intermediate level of obligation. Alternatively, the intermediate level could be stratified into “should” and “is appropriate.” Overlapping ranges of obligation may be acceptable as long as guideline developers make explicit the connection between deontic terms chosen and their intended level of obligation. One strategy would be to link deontic terms to grades of recommendation strength. In this approach, the number of deontic terms used would depend on the particular grading system applied by the guideline developers.

Limitations

Our response rate was low but consistent with response rates of internet-based surveys reported elsewhere.[33–35] Generalisabilty to a wider population of clinicians and consumers of practice guidelines may be limited. However, our sample included key target audiences, including clinicians, developers of practice guidelines, developers of performance measures, and developers of decisions support systems.

We wrote simplified recommendation statements within a deliberately vague clinical scenario in our best effort to isolate the effect of deontic terminology from other contextual features. Use of actual, published recommendations or an examination of other deontic terms may produce different responses. We also did not take into account word preferences (e.g., the use of “shall” vs. “should”) or cultural norms (e.g., American vs. British) that may impact how people interpret and use deontic terminology. We permitted each participant to use his or her own understanding of the concept of obligation and did not measure intra-rater variability.

Conclusion

A focus on deontic terminology is a small but important step towards producing guidelines with more predictable influences on clinical care.[36] “Must,” “should,” and “may” are well suited to represent three discrete levels of obligation recognized by the health services community. A standardised approach to the use of deontic terminology and the application of deontic terminology to systems for grading recommendation strength should be part of a larger set of standards for guideline development and presentation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Library of Medicine for their support.

Funding

This study was supported by grant R01-LM07199, which is co-funded by the National Library of Medicine and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contract AHRQ-07-10045, and by grant T15-LM07065 from the National Library of Medicine.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None.

Ethics approval

The Yale Human Investigations Committee approved our study under exemption status. The survey instrument did not collect any personally identifiable information.

Licence Statement

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Quality and Safety in Health Care and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://qhc.bmj.com/iforalicence.pdf).

REFERENCES

- 1.Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shekelle PG, Kravitz RL, Beart J, et al. Are nonspecific practice guidelines potentially harmful? A randomized comparison of the effect of nonspecific versus specific guidelines on physician decision making. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1429–1448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michie S, Johnston M. Changing clinical behaviour by making guidelines specific. BMJ. 2004;328:343–345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grol R, Dalhuijsen J, Thomas S, et al. Attributes of clinical practice guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ. 1998;317:858–861. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7162.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Becher OJ, et al. Reasons for pediatrician nonadherence to asthma guidelines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1057–1062. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.9.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiffman RN, Shekelle P, Overhage JM, et al. Standardized reporting of clinical practice guidelines: a proposal from the Conference on Guideline Standardization. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:493–498. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-6-200309160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The AGREE Collaboration. [accessed Nov 2008];Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument. Available from: http://www.agreecollaboration.org.

- 8.Shiffman RN, Dixon J, Brandt C, et al. The GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA): development of an instrument to identify obstacles to guideline implementation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Wright GH. Deontic logic. Mind. 1951;LX:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114:874–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West S, King V, Carey TS, et al. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2002;47:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [accessed Nov 2008];US Preventive Services Task Force Grade Definitions. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/grades.htm.

- 14.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. [accessed Jan 2009];London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; The guidelines manual (January 2009) 2009 :105–109. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk.

- 15.Shiffman RN, Liaw Y, Brandt CA, et al. Computer-based guideline implementation systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6:104–114. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1999.0060104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel VL, Kaufman DR. Cognitive science and biomedical informatics. In: Shortliffe EH, editor. Biomedical informatics: computer applications in health care and biomedicine. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 133–185. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georg G, Colombet I, Jaulent MC. Structuring clinical guidelines through the recognition of deontic operators. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;116:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain T, Michel G, Shiffman RN. The Yale Guideline Recommendation Corpus: a representative sample of the knowledge content of guidelines. J Med Informatics. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.11.001. Published Online First: 7 January 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13:227–236. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul-Dauphin A, Guillemin F, Virion JM, et al. Bias and precision in visual analogue scales: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:1117–1127. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillman DA, Smyth JD. Design effects in the transition to web-based surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5S):S90–S96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 4th edition. Lenoxa, Kansas: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2006. pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedlund W, Gronseth G, So Y, et al. [accessed Dec 2008];American Academy of Neurology Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual. 2004 Available from: http://www.aan.com/go/practice/guidelines/development.

- 24.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. [accessed Dec 2008];American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Reference Manual. 2008–2009 30:2. Available from: http://www.aapd.org/media/policies.asp. [PubMed]

- 25.ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. [accessed Dec 2008];Methodology Manual for ACC/AHA Guideline Writing Committees. 2006 Available from: http://www.acc.org/qualityandscience/quality/quality.htm.

- 26.Baumann MH, Lewis SZ, Gutterman D. ACCP evidence-based guideline development: a successful and transparent approach addressing conflict of interest, funding, and patient-centered recommendations. Chest. 2007;132:1015–1024. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Effective Practice Institute. Handbook for the preparation of explicit evidencebased clinical practice guidelines. New Zealand Guidelines Group; 2003. [accessed Dec 2008]. Available from: http://www.nzgg.org.nz/index.cfm?fuseaction=download&fusesubaction=template&libraryID=102. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reagan RT, Mosteller F, Youtz C. Quantitative meanings of verbal probability expressions. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74:433–442. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.74.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien BJ. Words or numbers? The evaluation of probability expressions in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39:98–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohnishi M, Fukui T, Matsui K, et al. Interpretation of and preference for probability expressions among Japanese patients and physicians. Fam Pract. 2002;19:7–11. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong A, Barnett GO, Mosteller F, et al. How medical professionals evaluate expressions of probability. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:740–744. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198609183151206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garber AM. Evidence-based guidelines as a foundation for performance incentives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:174–179. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leece P, Bhandari M, Sprague S, et al. Internet versus mailed questionnaires: a randomized comparison. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMahon SR, Iwamoto MI, Massoudi MS, et al. Comparison of e-mail, fax, and postal surveys of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e299–e303. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HL, Gerber GS, Patel RV, et al. Practice patterns in the treatment of female urinary incontinence: a postal and internet survey. Urology. 57:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00885-2. 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michie S, Johnston M. Changing clinical behaviour by making guidelines specific. BMJ. 2004;328:343–345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]