Abstract

Background

Screening colonoscopy has been offered in Germany since the end of 2002. Our aim was to estimate numbers of colorectal cancers prevented or detected early by screening colonoscopy in 2003–2010.

Methods

Participation rates and prevalences of advanced adenomas and colorectal cancers at screening colonoscopy in 2003–2008 were obtained from the national screening colonoscopy database by age, sex and calendar year. For 2009 and 2010, levels were assumed to remain at those observed in 2008. These data were combined in Markov models with population figures and estimates of transition rates from advanced adenomas to preclinical colorectal cancer and from preclinical cancer to clinically manifest cancer, accounting for total mortality.

Results

An estimated total number of 98 734 cases of colorectal cancer at ages 55–84 years are expected to have been prevented in Germany by removal of advanced adenomas by the end of 2010. These cancers might have become clinically manifest a median time period of 10 years after screening colonoscopy. Another 47 168 cases are expected to have been detected early at screening colonoscopy, often in a curable stage.

Conclusion

Despite limited participation, the German screening colonoscopy program makes a major contribution to prevention and early detection of colorectal cancer.

Bowel cancer is the second most common type of cancer and the second most common cause of death from cancer in Germany, in both men and women. On the basis of the latest data from the epidemiological cancer registries in Germany, the total numbers of new cases and deaths in 2006 were estimated at 68 740 and 27 125 respectively (1). More than 91% of new cases were in patients over the age of 55. Because bowel cancer develops slowly, via precursors which are easy to detect and completely curable, the chances of preventing it and detecting it early are significantly better than for other types of cancer.

The most important screening procedures are the fecal occult blood test and bowel endoscopy (2). Screening colonoscopy has been offered as part of cancer screening in Germany since October 2002. It is available to men and women aged 55 and older. If first performed before the age of 65, it can be repeated after 10 years (3).

The Central Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Funds and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians have linked the introduction of screening colonoscopies with a request to the Central Research Institute of Ambulatory Health Care in Germany (Zentralinstitut für die kassenärztliche Versorgung, ZI) for accompanying scientific research. Standardized reports of performed screening colonoscopies are gathered and evaluated at the ZI. As As payment for screening colonoscopies is contingent on submission of standardized reports, it can be assumed that all reports are entered (following some slight underascertainment initially).

This article aims to estimate the number of cases of colorectal cancer prevented or detected early up to the end of 2010 on the basis of currently available registry data. In this way the authors would like to make a contribution to assessing the impact of screening colonoscopies in the prevention and early detection of bowel cancer in Germany.

Materials and methods

Detected and removed advanced adenomas

In the first stage of our analyses, the number of screening participants in whom at least one advanced adenoma had been detected and removed as a result of screening colonoscopy was estimated. Advanced adenomas are direct precursors of colorectal cancer and if untreated progress to colorectal cancer within 10 years in approximately 30% to 40% of cases (4). Adenomas are classified as advanced if they are at least 1 cm in diameter or show a villous structure or a high degree of dysplasia.

The number of screening participants with advanced adenomas was calculated, stratified according to age, sex and calendar year, for the years 2003 through 2008 as products of the corresponding numbers in Germany’s population (5), the screening colonoscopy participation rates, and the prevalences of advanced adenomas. Prevalences were based on 2.82 million screening colonoscopies at ages ranging from 55 to 84 years in the national registry kept at the ZI. The average annual participation rate for the age range examined was 2.6% of those entitled to screening colonoscopies. The number of participants in whom existing colorectal cancer was detected early as a result of screening colonoscopy was estimated analogously, on the basis of the prevalences of detected carcinomas. For 2009 and 2010, for which not all national registry data are yet available, the corresponding numbers of detected advanced adenomas and carcinomas were calculated on the basis of population forecasts by the German Federal Statistical Office (5) and on the assumption that participation rates and prevalences remained constant between 2008 and 2010.

The registry kept at the ZI contains the screening colonoscopy data of the vast majority of the statutory health insured population entitled to screening (approximately 90%). Screening colonoscopies are also offered along similar lines to people with private insurance, but there are is no comparable registration of colonoscopy records for them. The calculations provided here were therefore based on the assumption that the participation rates and prevalences ascertained from ZI documents apply to the population as a whole.

Prevented colorectal cancer

Next, in the second stage, the number of cases of prevented preclinical carcinoma in the age range 55 to 84 years was estimated, again stratified according to age and sex. Estimates were derived from a Markov model in one-year steps from the age at which the adenoma was removed to a maximum of 85 years of age. Age- and sex-specific transition rates, which had been estimated in an earlier paper on the basis of cancer registry data (4), and age- and sex-specific death rates for the Federal Republic of Germany from 2004 to 2006 (5) were used as the basis for this.

Finally, in the third stage, the number of cases of prevented clinically manifest carcinomas in the age range from 55 to 84 years was estimated, once again stratified according to age and sex. Here again, a Markov model was used with one-year steps from the age of onset of preclinical carcinoma to a maximum of 85 years of age. Calculations were based on an estimated average duration of 3.6 years for the preclinical phase of colorectal carcinoma (corresponding to an annual transition rate from the preclinical to the clinical phase of 17.5%) (6, 7) and, again, the age- and sex-specific death rates from 2004 to 2006 (5). Consideration of the death rates ensures that only cases of bowel cancer which would have become clinically manifest during patients’ lifetimes are included. For a fuller description of the modelling principle used here, the authors refer to earlier papers (8, 9).

The assumptions which underlie the authors’ projections are summarized in the Box. In order to assess the sensitivity of estimates regarding the assumptions made, the authors repeated the analyses and used death rates 10% lower in order to allow for the potential effect of an expected further increase in life expectancy. The authors also altered the transition rates from advanced adenoma to preclinical carcinoma (4) and from preclinical carcinoma to clinically manifest carcinoma, which were based on the estimates in earlier papers (6, 7), by ±20%.

Box. Assumptions underlying projections.

Demographic changes in 2009 and 2010: forecasts of the German Statistical Office (5).

Age- and sex-specific rates of participation in screening colonoscopy and prevalences of advanced adenomas in 2009 and 2010 are the same as in 2008.

Age- and sex-specific rates of participation in screening colonoscopy and prevalences of advanced adenomas in the population as a whole are the same as the figures for people with statutory health insurance.

Annual transition rates from advanced adenomas to preclinical carcinomas are as shown in Table 2 (sensitivity analyses: transition rates 20% higher or lower).

Annual transition rates from preclinical adenomas to clinically manifest carcinomas: 17.5%, corresponding to a median preclinical phase duration of 3.6 years (sensitivity analyses: 14%, 21%).

Age- and sex-specific death rates of screening colonoscopy participants are the same as the national averages from 2004 to 2006 (sensitivity analyses: 10% lower).

-

Not examined:

Carcinomas prevented by detection and removal of non-advanced adenomas

Carcinomas prevented by detection and removal of advanced adenomas in subsequent follow-up colonoscopies

Carcinomas prevented by detection and removal of more than one advanced adenoma

Onset of carcinomas following incomplete removal of advanced adenomas or advanced adenoma recurrence

Carcinomas which would have been detected by other means (e.g. by chance or in other diagnostic procedures) before clinical manifestation

Results

Table 1 shows the estimated numbers for men and women in whom a colorectal carcinoma was detected early or at least one advanced adenoma was detected and removed up to the end of 2010 through the use of screening colonoscopy. The estimated number of carcinomas detected early is 47 168. More than 60% of these were in men, and the median age of participants with carcinomas detected early was within the range 65 to 69 years. The estimated number of participants in whom no carcinoma was found but at least one advanced adenoma was detected and removed is almost 330 000. Here too, approximately 60% of cases were in men, and more than half of cases were detected in the age groups 60 to 64 and 65 to 69 years.

Table 1. Expected numbers of participants in screening colonoscopy in Germany in whom a carcinoma or at least one advanced adenoma (but no carcinoma) was detected between 2003 and 2010 (stratified according to age and sex).

| Age | Carcinoma detected early | Advanced adenoma detected | ||||

| Men | Women | Total | Men | Women | Total | |

| 55–59 | 3515 | 2375 | 5890 | 38 074 | 27 563 | 65 637 |

| 60–64 | 6068 | 3690 | 9758 | 51 318 | 33 507 | 84 825 |

| 65–69 | 7714 | 4852 | 12 566 | 54 373 | 34 159 | 88 532 |

| 70–74 | 6535 | 3848 | 10 383 | 33 733 | 21 910 | 55 643 |

| 75–79 | 3713 | 2740 | 6453 | 15 930 | 11 725 | 27 655 |

| 80–84 | 1222 | 895 | 2118 | 3835 | 2474 | 6309 |

| Total | 28 767 | 18 400 | 47 168 | 197 263 | 131 338 | 328 601 |

Although most colorectal carcinomas progress from advanced adenomas, not all advanced adenomas would progress to clinically manifest carcinomas within patients’ lifetimes. As shown in Table 2, the estimated annual transition rates from advanced adenomas to preclinical carcinomas in those aged under 65 are only around 3%. Although they increase with age, even in those aged over 70 they only reach around 5%. The (age-independent) average duration of carcinomas at a preclinical stage is estimated at approximately 3.6 years (6, 7).

Table 2. Estimated annual transition rate (%) from advanced adenomas to preclinical carcinomas (stratified according to age and sex) (source: [4]).

| Age | Annual transition rate (%) | |

| Men | Women | |

| 55–59 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| 60–64 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| 65–69 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| 70–74 | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| 75–79 | 4.5 | 5.8 |

| 80–84 | 5.1 | 5.6 |

Nevertheless, as shown in Table 3, the number of carcinomas prevented by removal of advanced adenomas—i.e. carcinomas which one would expect to have become clinically manifest within patients’ lifetimes and before the age of 84 if the adenomas had not been removed—is almost 100 000 in total. Once again, around 60% of cases are in men. The median time between colonoscopy and carcinoma manifestation expected without colonoscopy and removal of advanced adenoma is 10 years.

Table 3. Expected numbers of participants in screening colonoscopy in whom a clinically manifest carcinoma was prevented before the age of 84 by detection and removal of an advanced adenoma between 2003 and 2010 (stratified according to length of time after colonoscopy).

| Years after colonoscopy | Carcinoma prevented | ||

| Men | Women | Total | |

| 1–5 | 13 334 | 8837 | 22 171 |

| 6–10 | 19 120 | 12 624 | 31 744 |

| 11–15 | 14 775 | 9796 | 24 571 |

| 16–20 | 8157 | 5513 | 13 670 |

| 21–25 | 3215 | 2250 | 5465 |

| 26–30 | 646 | 467 | 1113 |

| Total | 59 247 | 39 487 | 98 734 |

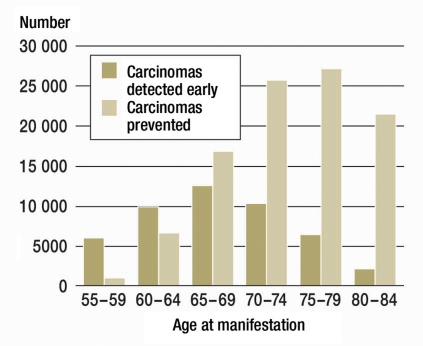

The peak for carcinomas prevented by colonoscopy and removal of advanced adenomas is in the age groups 70 to 74 and 75 to 79 years (median: 74 years, Table 4) compared to a peak in the age groups 60 to 64 and 65 to 69 for advanced adenomas and carcinomas detected early by screening colonoscopy.

Table 4. Expected numbers of participants in screening colonoscopy in whom a clinically manifest carcinoma was prevented before the age of 84 by detection and removal of an advanced adenoma between 2003 and 2010 (stratified according to age at manifestation of carcinoma).

| Age | Carcinoma prevented | ||

| Men | Women | Total | |

| 55–59 | 610 | 440 | 1050 |

| 60–64 | 3852 | 2713 | 6565 |

| 65–69 | 10 016 | 6781 | 16 797 |

| 70–74 | 15 484 | 10 229 | 25 713 |

| 75–79 | 16 318 | 10 725 | 27 043 |

| 80–84 | 12 965 | 8 599 | 21 564 |

| Total | 59 247 | 39 487 | 98 734 |

The numbers and age range for carcinomas detected early and prevented by screening colonoscopy are displayed in the Figure.

Figure.

Expected numbers of colorectal carcinomas detected early and prevented as a result of screening colonoscopy in Germany between 2003 and 2010, by age group

In sensitivity analyses, the assumption of a 10% fall in total mortality leads to only a comparatively small increase in the total number of cases prevented (from 98 734 to 101 938). Changes in the transition rates from advanced adenomas to preclinical carcinomas or the transition rate from preclinical carcinomas to clinically manifest carcinomas of ±20% resulted in variations in the number of clinically manifest carcinomas prevented between 83 304 and 112 516 and between 90 086 and 105 231 respectively.

Discussion

With the introduction of screening colonoscopy at the end of 2002, Germany embarked on a completely new course in colorectal cancer prevention and thereby took on an internationally leading role (10, 11). Swift evaluation of the achieved results should be a matter of urgency for health policy-related decisions regarding extension of and possible changes to the program. As the model calculations presented here show, monitoring the development of incidence and mortality rates alone is of only limited use for this, as many of the expected effects concerning prevented carcinomas only become fully appreciable following a long latency period. In addition, changes in incidence rates are also obscured by predated diagnosis of carcinomas which are detected early, particularly in the initial years of the screening program (12, 13). The model calculations presented here are therefore intended as an additional timely contribution to interim appraisal of screening colonoscopy in Germany after eight years.

According to our estimates, between 2003 and 2010 almost 100 000 cases of colorectal cancer were prevented by the detection and removal of advanced adenomas. This figure is almost twice the annual number of new cases of bowel cancer observed to date in the age group 55 to 84 (1). In addition, in almost 50 000 participants existing colorectal cancer was detected earlier and therefore much more frequently at a curable stage. In cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed through the use of screening colonoscopy, the proportion of cases detected at stages I or II is approximately 70% (14– 16), whereas according to data from population-based studies this proportion is generally less than 50% (17). Early detection of these cancers should therefore have made a further significant contribution to reducing colorectal cancer mortality.

As in all the model calculations, the underlying assumptions and their effect on the results must be interpreted with care. The ZI’s nationwide documentation of screening colonoscopy provided the authors with a unique data source with which to estimate age- and sex-specific participant rates and prevalences of carcinomas and advanced adenomas for the years 2003 to 2008. The corresponding data for 2009 and 2010 were not yet available when this analysis was carried out, and so the data for 2008 were used instead. In view of the great consistency of these parameters from 2003 to 2008, this procedure seems justified, and any moderate changes in these figures in 2009 and 2010 would have only a comparatively small effect on the estimated total numbers of prevented carcinomas and carcinomas detected early. Continuation of the observed trend towards somewhat higher prevalences of advanced adenomas (18) would result in a somewhat increased number of prevented carcinomas.

ZI documents only screening colonoscopies of those with statutory health insurance. In our analyses, we assumed comparable participation rates and prevalences of conspicuous findings in the rest of the population, most members of which were privately insured. As this concerns only a minority of approximately 10% of the population, even if there were major discrepancies from the assumed participation rates and prevalences, this would not have a substantial effect on the estimates given here for prevented carcinomas in the population as a whole.

Using a conservative approach, we based our main analysis on mortality rates that were assumed to remain constant over time. However, it would probably be more realistic to assume the decades-old trend towards falling mortality to continue. As shown by sensitivity analyses, this would yield somewhat higher numbers of prevented carcinomas and carcinomas detected early. Sensitivity analyses also show that the order of magnitude of the estimates does not change significantly even if there are major variations in the underlying transition rates from advanced adenomas to preclinical carcinomas and from preclinical carcinomas to clinically manifest carcinomas.

One thing not covered by the analysis was the additional prevention of colorectal cancer as a result of the detection and removal of non-advanced adenomas. The number of such cases is significantly higher than the number of detected and removed advanced adenomas. Although the transition rates of these adenomas into carcinomas are significantly lower, their removal also makes a substantial contribution to bowel cancer prevention in the long term. Also excluded from the analysis were the prevention of colorectal cancer in those over 84 years of age and the detection and removal of multiple advanced adenomas in a single person. This is another reason why the figures for prevented carcinomas are conservative estimates.

Our analyses cannot and should not replace a comprehensive cost/benefit assessment of screening colonoscopy. Cost/benefit analyses already available and the rapidly rising costs of chemotherapy suggest that savings achieved due to prevented cases of colorectal cancer significantly exceed the costs of screening colonoscopy, including the cost of treating complications and follow-up examinations after polypectomies (12, 19). An analysis of 245 000 outpatient colonoscopies in the German federal state of Bavaria revealed 69 cases of intestinal perforation (0.03%), 50 of which required surgery, and three deaths due to cardiorespiratory complications (0.001%) (20). Even if additional complications in the preparatory phase and in the time following colonoscopy are taken into account, frequencies of severe complications will therefore likely be very substantially lower than the expected frequencies of prevented carcinomas and deaths associated with them.

Limitations

When interpreting the estimates, it should be borne in mind that they only take into account carcinomas prevented by removal of advanced adenomas as a result of primary screening colonoscopies. Other carcinomas were prevented by detection and removal of advanced adenomas following colonoscopies performed in order to clarify positive results of fecal occult blood tests or pain. There were substantially more of these “curative colonoscopies” than screening colonoscopies (20). Although reimbursement schemes make a distinction between screening colonoscopies and curative colonoscopies, it is often impossible to be sure of the reason for a colonoscopy. This is because on the one hand patients may opt for a screening colonoscopy because of initial symptoms, for example, and on the other hand they may abstain from undergoing screening colonoscopy because a curative colonoscopy may already have been performed (21). The increasing numbers of curative colonoscopies performed even before 2003 might also explain the fall in incidence of colorectal cancer observed in the meanwhile (1).

Conclusion

Despite limitations due to the available data and the uncertainties regarding the assumptions on which the projections are based, the analyses do show that screening colonoscopy has already made a major contribution to the prevention of colorectal cancer in its first eight years, even if the effects only become noticeable after a certain latency period in the form of reduced incidence rates. According to an earlier analysis, only approximately 15 000 of the nearly 100 000 prevented cases of bowel cancer in the age group 55 to 84 would have become clinically manifest by the end of 2010 (8). It is striking that these major effects were achieved even with the still rather low participation rates: approximately 3% of those entitled every year. Much greater effects would be achieved if uptake of screening colonoscopy could be further improved. On the basis of the experience of other countries and other screening programs, this could probably be done via an organized screening program with targeted invitation of those entitled to take part. As part of the German National Cancer Plan, recommendations for gradually moving forward such a program are currently being developed. In addition, a concurrent thorough scientific evaluation of the screening program is important. This should contain a comprehensive, further differentiated (for example, by location of cancer) assessment of its effectiveness (22– 24), possible risks (19), and costs and benefits (13, 19, 20).

Key Messages.

In the first eight years of the German screening colonoscopy program, advanced adenomas were detected and removed in more than 300 000 participants (based on projected data for 2009 and 2010).

Over the same period, approximately 50 000 colorectal carcinomas were detected early as a result of screening colonoscopies. Most of these were detected at a curable stage.

According to projections, approximately 100 000 colorectal carcinomas were prevented in the age group 55 to 84 years by detection and removal of these advanced adenomas.

These carcinomas would have become clinically manifest a median of 10 years after screening colonoscopy.

Improving the rate of participation in screening colonoscopy (e.g. using targeted invitations) would result in substantially higher prevention potential.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Devitt, MA.

Sponsorship: Parts of this work were made possible by project sponsorship provided by Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Aid) (project 108230), the Central Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Gesellschaft der Epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland (GEKID), Robert Koch-Institut (Herausgeber) Häufigkeiten und Trends, 7. Ausgabe. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut; 2010. Krebs in Deutschland 2005/2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmiegel W, Pox C, Reinacher-Schick A, et al. S3-Leitlinie „Kolorektales Karzinom“. Ergebnisse evidenzbasierter Konsensuskonferenzen am 6./7. Februar 2004 und 8/9 Juni 2007 (für die Themenkomplexe IV, VI und VII) Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:1–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung. Früherkennung des Kolonkarzinoms Ergänzung der bestehenden Maßnahmen um die qualitätsgesicherte, hohe Koloskopie. Dtsch Arztebl. 2002;99(40):A 2648–A2650. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Stegmaier C, Brenner G, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Risk of progression of advanced adenomas to colorectal cancer by age and sex: estimates based on 840 149 screening colonoscopies. Gut. 2007;56:1585–1589. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online, last accessed. 2010. Mar 13,

- 6.Eide TJ. Risk of colorectal cancer in adenoma-bearing individuals within a defined population. Int J Cancer. 1986;38:173–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loeve F, Brown ML, Boer R, Habbema JD. Endoscopic colorectal cancer screening: a cost-saving analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:557–563. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Brenner G, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Expected reduction of colorectal cancer incidence within 8 years after introduction of the German screening colonoscopy programme: Estimates based on 1 875 708 screening colonoscopies. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2027–2033. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner H, Altenhofen L, Hoffmeister M. Estimated long-term effects of the initial 6 years of the German screening colonoscopy program. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:784–789. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pox C, Schmiegel W, Classen M. Current status of screening colonoscopy in Europe and in the United States. Endoscopy. 2007;39:168–173. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pox C, Schmiegel W. Colorectal cancer screening in Germany. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46(Suppl 1):S31–S32. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoff G, Grotmol T, Skovlund E, Bretthauer M. Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention Study Group. Risk of colorectal cancer seven years after flexible sigmoidoscopy screening: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JM, Parkin DM, Wardle J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Trial Investigators. Lancet. 2010;375:1624–1633. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sieg A, Theilmeier A. Results of colonoscopy screening in 2005—an Internet based documentation. [Ergebnisse der Vorsorge-Koloskopie 2005] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:379–383. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieg A, Brenner H. Cost-saving analysis of screening colonoscopy in Germany. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45:945–951. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bokemeyer B, Bock H, Hüppe D, et al. Screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer prevention: results from a German online registry on 2690.00 cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:650–655. doi: 10.1097/meg.0b013e32830b8acf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, Stürmer T, Hoffmeister M. Does a negative screening colonoscopy ever need to be repeated? Gut. 2006;55:1145–1150. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner H, Altenhofen L, Hoffmeister M. Sex, age and birth cohort effects in colorectal neoplasms: a cohort analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:697–703. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Habbema JD, Kuipers EJ. Effect of rising chemotherapy costs on the cost savings of colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1412–1422. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crispin A, Birkner B, Munte A, Nusko G, Mansmann U. Process quality and incidence of acute complications in a series of more than 2300.00 outpatient colonoscopies. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1018–1025. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wuppermann D, Wuppermann I, Riemann JF. Aktueller Wissensstand der Bevölkerung zur Darmkrebsvorsorge - eine Untersuchung der Stiftung LebensBlicke mit dem Institut für Demoskopie in Allensbach. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:1132–1136. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, Stürmer T, Hoffmeister M. Potential for colorectal cancer prevention of sigmoidoscopy versus colonoscopy: population-based case control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:494–499. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer: a population-based, case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:1–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Protection from right- and left-sided colorectal neoplasms after colonoscopy: population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:89–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]