Abstract

This is the first report of a poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthase in Escherichia coli. The enzyme was isolated from the periplasm using ammonium sulfate fractionation, hydrophobic, and size-exclusion chromatography and identified by LC/MS/MS as YdcS, a component of a putative ABC transporter. Green Fluorescent Protein-tagged ydcS, purified by 2D native gel electrophoresis, also exhibited PHB synthase activity. Optimal conditions for enzyme activity were 37 °C, pH 6.8–7.5, 100 mM KCl. Km was 0.14 mM and Vmax was 18.7 nmol/mg protein/min. The periplasms of deletion mutants displayed <25% of the activity of the parent strain. Deletion mutants exhibited ~25% less growth in M9 medium, glucose, and contained ~30% less PHB complexed to proteins (cPHB) in the outer membranes, but the same concentration of chloroform-extractable PHB as wild-type cells. The primary sequence of YdcS suggests it may belong to the alpha/beta hydrolase superfamily which includes polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthases, lipases and esterases.

Keywords: polymerase, hydroxybutyrate, periplasmic enzyme, protein modification

Introduction

Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthases catalyze the polymerization of R-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA to high molecular weight polymer (>60,000 units) in many soil and water bacteria [1–3]. However, synthases that produce the short polymers of R-3-hydroxybutyrate (< 200 units), which are ubiquitous components of all cells – prokaryotic and eukaryotic [4–7], remain unknown. These short polymers are found complexed to other macromolecules and thus are referred to as cPHB.

Escherichia coli does not synthesize high molecular weight PHB, but it contains cPHB (~ 140 units) associated with inorganic polyphosphate in the cytoplasmic membranes [5,6], and ~ 5% of its proteins are modified by cPHB [7–9]. Theodorou et al [10] showed that the AtoS-AtoC signal transduction system in the cytoplasmic membrane, which induces the atoDAEB operon for growth with short-chain fatty acids, can positively modulate the levels of cPHB biosynthesis in E. coli. They suggest that periplasmic acetoacetate acts as an inducer. Here we examine the distribution of cPHB synthase activity in cell fractions of E. coli, and isolate a periplasmic protein with cPHB synthase activity which is a potential participant in the cPHB modification of some E. coli outer membrane proteins.

Materials and methods

Strains

E. coli clones of ydcS deletion mutants (JWK1435-1,2) and parent strain (BW25113), His-tagged and GFP-tagged ydcS (JW1435-His; JW1435-GFP) were obtained from the National BioResource Project, Japan [11].

Cell fractionation

Cells of E. coli BW25113, were cultured in LB medium, collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 mM KHepes, pH 7.3. Lysozyme (20µg/ml) and EDTA (1 mM) were added and the cell suspension was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. DNase (50 µg/ml), RNase (50 µg/ml) and MgCl2 (5 mM) were added, and the cells were broken by ultrasonication. Unbroken cells were removed by low speed centrifugation, and the supernatant (S3K) was centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 60 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellet (P18K) was saved, and the supernatant (S18K) was centrifuged at 45,000 rpm for 2½ hrs at 4 °C. The envelope fraction (P18K pellet) was further separated into cytoplasmic membrane, and outer membrane fractions on sucrose step gradients as previously described [12]. NADH oxidase activity was used as a marker for cytoplasmic membranes [13] and ketodeoxyoctanoate was used as a chemical marker for outer membranes [14]. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay.

Preparation of periplasmic fraction

Periplasmic fractions were isolated by osmotic shock using the method of Nossal and Heppel [15]. The periplasmic fraction contained < 4% of the KDO activity of the outer membrane fraction per mg protein and < 7% of the NADH oxidase activity of the cytoplasmic membranes per mg protein.

Radioactive assay for PHB synthase

The reaction mixture (100 µl) contained 10 µl sample, 6 µl of 14C-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA (50 mCi/mmole; 0.1 mCi/ml.), 0.1 mM 3-HB-CoA, 0.4 mg BSA, 10 µg E. coli phospholipids, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM KHepes, pH 7.4. A reaction mixture without added sample was included in each group of assays. The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr, and cooled on ice. An equal volume of ice-cold 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added and mixtures were incubated on ice for 1 h. The precipitates were collected on Whatman GF/F filters in a Millipore 1225 Sampling Manifold, washed 3x with 3 ml 10% TCA, then 2x with acetone. The dry filters were added to scintillation fluid, and radioactivity was determined in a Beckman Model LS6500 scintillation counter.

Co-A release assay for PHB synthase

Release of CoA during oligomerization of 3-HB-CoA was measured in a discontinuous assay [16,17]. The reaction mixture (100 µl) contained 10 µg periplasmic fraction or 1 µg YdcS-GFP, 1 mM 3-HB-CoA, 10 µg E. coli total phospholipids, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM KHepes, pH 7.5. The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr, then 7.7 µl 100% TCA was added to stop the reaction and the mixture was cooled on ice. After centrifugation to remove precipitated protein, supernatant (102 µl) was added to 573 µl of 1 mM DNTB (5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid), in 0.5 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.8, and A412 was measured. A standard curve of CoA (Sigma) versus A412, measured in the same medium, was used to convert A412 to CoA.

Chemical assay for cPHB

The procedure used is an adaptation of the method of Karr et al. [18] as described by Huang and Reusch [7].

Liquid chromatography/Mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS)

The gel band was subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion according to Jensen et.al. [19]. The extracted peptides were automatically injected by a ThermoElecton Micro-Autosampler onto an Agilent Zorbax 300 SB-C18 5 × 0.3 mm peptide trap. The bound peptides were eluted onto a 15 cm × 75 µm Microm Magic C18 AQ column (Michrom BioResources , Auburn, CA) and then eluted with a gradient of 5% B to 90% B using a ThemoElectron Surveyor LC (Buffer A = 99.9% Water/0.1% formic acid, Buffer B = 99.9% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid) into a ThermoElectron LTQ-FTICR mass spectrometer. Survey scans were subjected to automatic low energy collision-induced dissociation (CID) in the LTQ. The resulting MS/MS spectra were converted to peak lists using BioWorks Browser v 3.2 and searched against a database consisting of all E. coli sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Identifications were considered positive when 2 peptides per protein were identified with a significant Mascot score (p< 0.05).

Purification of YdcS

(NH4)2SO4 was added to 45% saturation to the periplasmic fraction obtained from E. coli BW25113 cells. After incubation for 2 h at 4 °C, the mixture was centrifuged, and the pellet dissolved in 20mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1 M (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1mM DTT and loaded onto a HiPrep 16/10 phenyl FF (high sub) column. Elution was with a linear gradient of (NH4)2SO4 (1 M to 0 M) in 20 mM Tris, pH7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT. Fractions were tested for PHB synthase activity by the radioactive assay, and the active fractions were pooled and loaded onto a HiPrep 16/10 Q FF column. Elution was with a linear gradient of NaCl (0–1M), 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT. Active fractions were pooled and an aliquot was loaded onto a Superdex 75 column. Elution was with 20mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, pH 7.5.at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min; fractions with PHB synthase activity eluted at ~20 ml.

Purification of GFP- YdcS

An ASKA E. coli ydcS-GFP fusion (JW1435-GFP) (NBRP, Japan) was grown in LB medium and ydcS-GFP was overexpressed by addition of 0.2 mM IPTG and culture o/n at 30 °C. The cells were harvested and resuspended in 20 mM Tris, 100mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 2 mM DTT, pH 7.5. After adding lysozyme (20 µg/ml), RNase (10 µg/ml), and DNase to (5 µg/ml), cells were broken by ultrasonication. Unbroken cells were removed by low speed centrifugation and (NH4)2SO4 was added to the supernatant to 45% saturation. The pellet was collected and dissolved in 20mM Tris, 1 M (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5, and loaded onto a HiPrep 16/10 phenyl FF (high sub) column. YdcS-GFP protein was eluted with a linear gradient of (NH4)2SO4 (1M −0 M), and fractions displaying green fluorescence were pooled, and filtered. An aliquot of this solution was loaded onto a Superdex 75 column equilibrated with 10mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5. Elution was with the same solvent at 0.5 ml/min. Purified YdcS-GFP was quantified by its fluorescence, using a standard curve of fluorescence intensity versus YdcS-GFP concentration (Millipore).

2-D gel electrophoresis of YdcS-GFP

YdcS-GFP was subjected to 2D electrophoresis using a Mini Protean II 2D cell (Bio-Rad). Sample buffer contained 5% DTT, 1.6% 5–7 ampholytes, 0.4% 3–10 ampholytes, 0.1% octyl glucoside, 10% glycerol. First dimension was 4% acrylamide (tube gel), 0.1% octyl glucoside, 1.6% 5–7 ampholytes, 0.4% 3–10 ampholytes. Anode buffer was 7M phosphoric acid; cathode buffer was 20 mM lysine, 20 mM arginine. Electrophoresis was at 500 V for 10 min and 750 V for 3.5 hr. Second dimension was in a native 12% acrylamide gel, 25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine buffer, pH 7.3. Electrophoresis was at 160 V until the dye front reached the bottom of the gel.

cPHB from log-phase and competent cell

Cells were cultured in SOB medium [21] with high aeration (275 rev/min) to A600 of 0.4. The culture was cooled on ice and then equally divided. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1800 rpm for 15 min at 4° C. One cell pellet was resuspended in ice-cold SOB medium, and the other in 1/3 volume of ice cold transformation buffer (10 mM KMES (pH 6.2), 100 mM KCl, 45 mM MnCl2, 10 mM CaCl2) and incubated on ice for 30 min [21]. The cells were collected by centrifugation, and washed twice with ice-cold dry acetone. The dry pellets were extracted 2x with 2 ml. warm chloroform (30 °C). The chloroform extracts were filtered and chloroform was evaporated with a stream of dry nitrogen. The residues were assayed for cPHB using the chemical assay.

Results

Cellular distribution of PHB synthase activity in E. coli

Late log-phase E. coli BW25113 cells were lysed by ultrasonication. The low-speed pellet (P3K) was discarded and the supernatant (S3K) was separated into the following density fractions: envelope fraction (P18K), cytoplasm (S18K), ribosomal fraction (P45K) and cytosolic fraction (S45K). PHB synthase activity was assayed in each fraction by following the conversion of water-soluble 14C- 3-HB-CoA into TCA-insoluble oligomers.

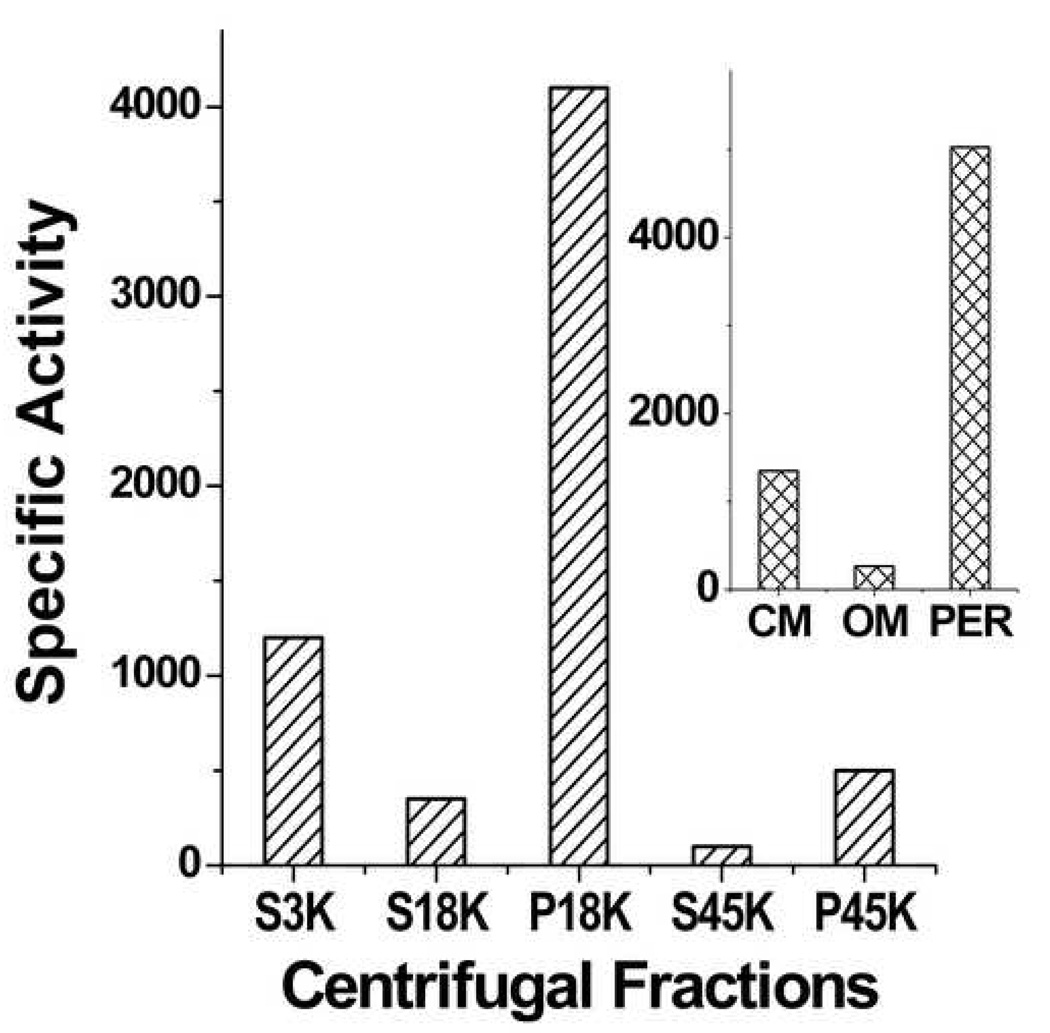

As shown in Figure 1, the highest specific activity (cpm/mg protein) was in the envelope fraction. This fraction was further separated on sucrose density step-gradients into cytoplasmic membrane and outer membrane fractions. Cytoplasmic membranes contained ~ 20% and outer membranes ~ 4% of the total activity (Fig. 1 insert). The periplasmic fraction, isolated from whole cells by osmotic shock, accounted for the ~75% remaining activity. The activity was very labile, decreasing at a rate of 60% per day at 4 °C, 25% per day at −20 °C and 12% per day at −80 °C. Addition of E. coli lipids, glycerol, dithiothreitol, various detergents and salts, either individually or in combination, did not stabilize the enzyme activity.

Figure 1.

PHB synthase activity in centrifugal fractions of E. coli BW25113 lysates. S-supernatant; P pellet. Insert shows distribution of activity in P18K fractions (envelope fractions). CM: cytoplasmic membrane; Per: periplasm; OM: outer membrane. Specific activity; counts per minute per mg protein.

Purification of an PHB synthase from E. coli periplasm

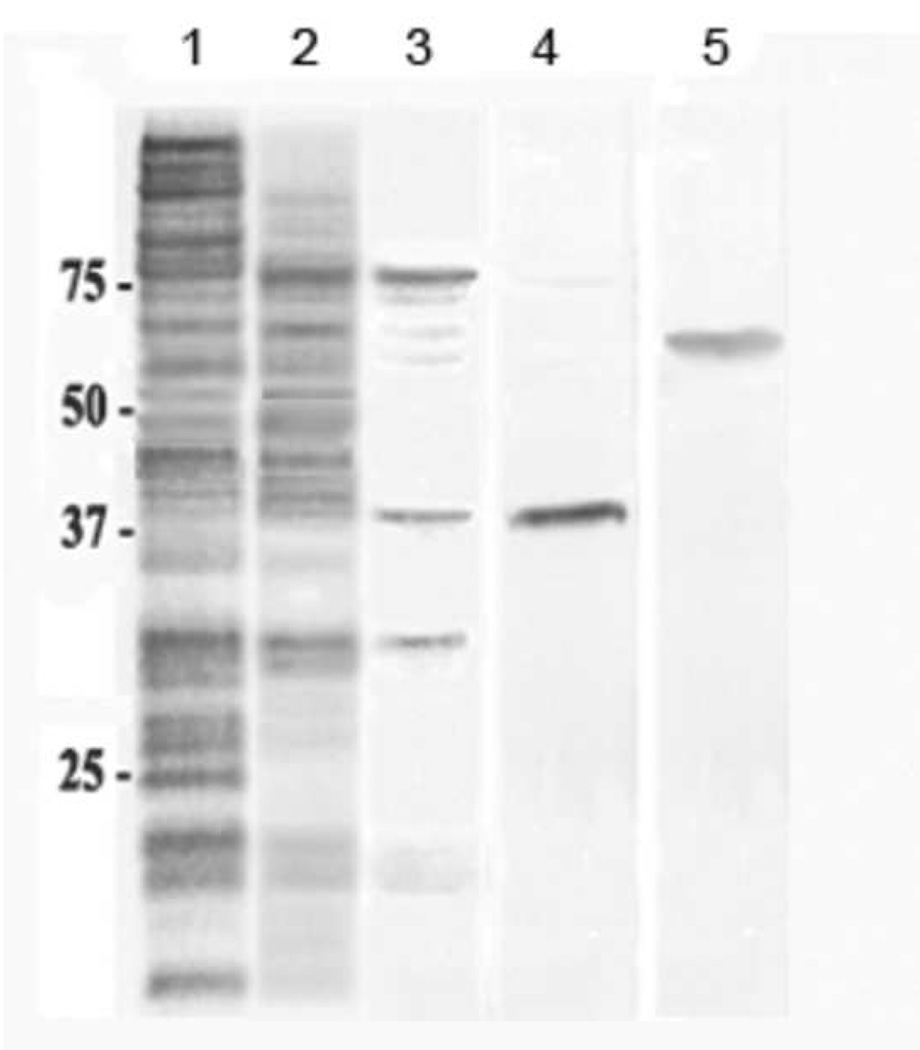

A PHB synthase was purified from the periplasm of stationary-phase E. coli BW25113 cells (Table 1). Coomassie blue stain of an SDS-PAGE showed a protein band at ~ 40 kDa (Fig. 2, lane 4). The purified protein demonstrated significant PHB synthase activity when tested with the radioactive assay (420 cpm/µg) but the activity was even more labile than that of the periplasmic fraction. LC/MS/MS of a similar band identified the protein as YdcS, a putative member of an ABC transporter [20].

Table 1.

Purification of YdcS from periplasmic fraction derived from late log-phase E. coli BW25113 cells.

| Fraction | Total activity (cpm) |

Total Protein (mg) |

Specific activity (cpm/mg) |

Yield (%) |

Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periplasm | 23,662,292 | 4500 | 5,258 | 100 | 1 |

| Ammonium Sulfate | 10,274,392 | 545 | 18,852 | 43 | 3.6 |

| Phenyl FF | 2,630,672 | 57 | 46,152 | 11 | 8.8 |

| Q FF | 687,704 | 5.9 | 116,560 | 3 | 22.2 |

| Superdex 75a | 463,821 | 2.4 | 193,259 | 2 | 37.6 |

Only 10% of Q FF fraction was subjected to Superdex 75 chromatography yielding 0.24 mg purified protein.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE gels (12%) of fractions obtained during the purification of YdcS from periplasm of E. coli BW25113 cells . The gels were stained with Coomassie Blue. Lane 1: 45% ammonium sulfate precipitant; lane 2: active fractions from HiPrep 16/10 phenyl FF column chromatography; lane 3: active fractions from HiPrep 16/10 Q FF column chromatography; lane 4: YdcS after Superdex 75 column chromatography; lane 5: YdcS-GFP purified by the same sequence after Superdex 75 chromatography.

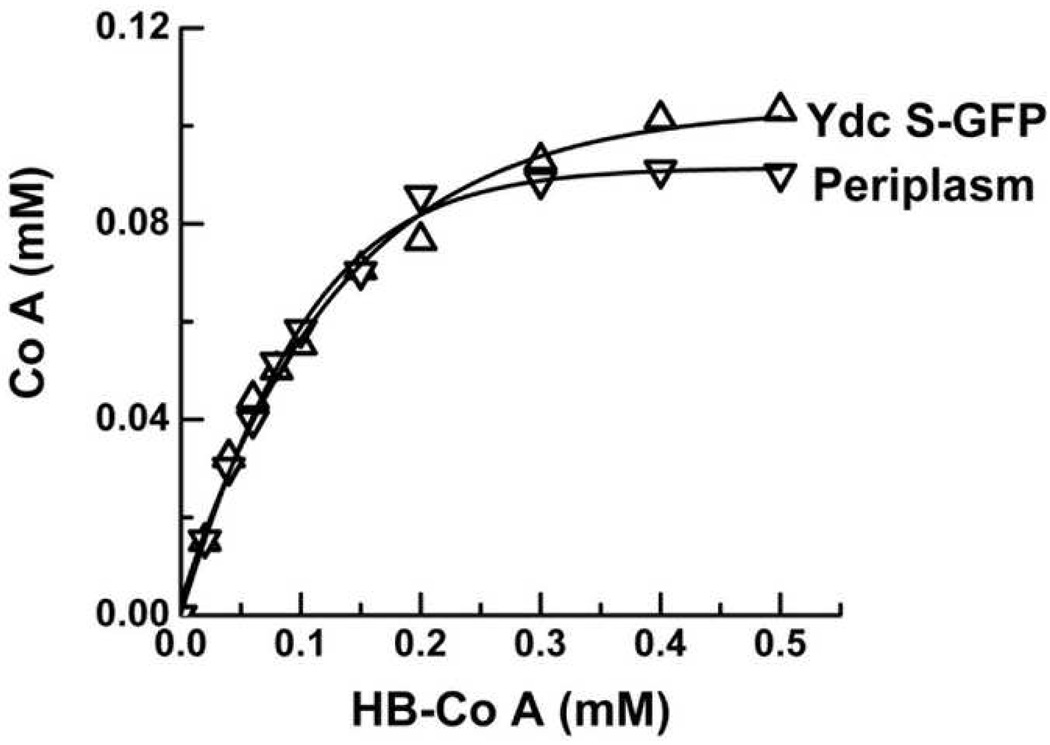

Purification and PHB synthase activity of YdcS-GFP

To confirm the PHB synthase activity of YdcS, ASKA clones of His-tagged and GFP-tagged ydcS were obtained from the National BioResource Project E. coli strain (NBRP, Japan). Clones of His-tagged ydcS exhibit high toxicity and almost no growth after IPTG induction whereas clones of GFP-tagged ydcS exhibit very high fluorescence following IPTG induction. The green fluorescence was used instead of the radioactive assay to identify YdcS-GFP fractions and to quantify YdcS-GFP. The purified YdcS-GFP (13 µg from 100 ml culture) exhibited significant PHB synthase activity in both radioactive (860 cpm/µg protein) and CoA-release assays. The PHB synthase activity was proportional to the enzyme concentration. YdcS-GFP was further purified by 2D native gel electrophoresis to rule out co-migration with a protein of the same MW. The band containing YdcS-GFP displayed significant PHB synthase activity by the radioactive assay (456 cpm/µg). YdcS-GFP was somewhat more stable than periplasmic YdcS, but was inactivated by incubation at 70 °C for 20 min.

The identity of cPHB as the product of ydcS-GFP activity in the radioactive assay was further tested with a chemical assay for cPHB. The crotonic acid formed in this procedure was found to contain 14C-crotonic acid (2162 cpm). The same procedure performed without YdcS-GFP, yielded no radioactive crotonic acid.

Enzyme characteristics of YdcS

Due to the rate at which YdcS and YdcS-GFP lost activity, freshly prepared periplasm was used to determine the enzyme characteristics. Once the activity curves were established, the maxima were confirmed using purified YdcS-GFP and/or YdcS. The optimum conditions for the enzyme were a temperature of 37 °C, pH of 6.8–7.8, and ionic strength of 100 mM. A Lineweaver plot indicated a Km of 0.14 mM and Vmax of 18.7 nmol/mg protein/min.

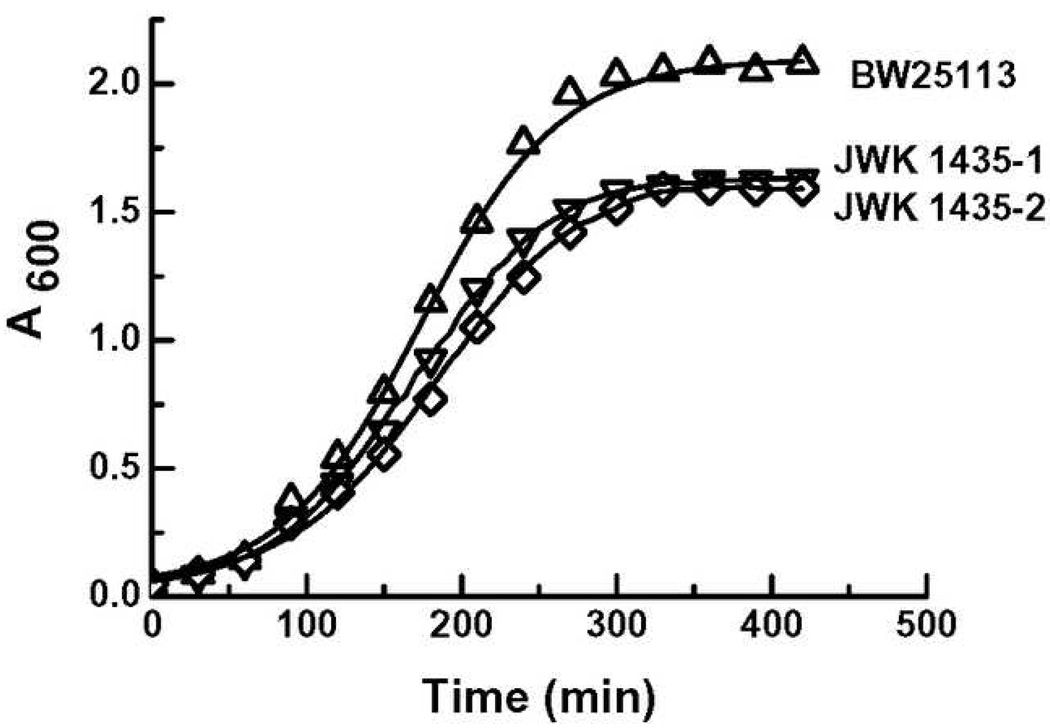

Effect of ydcS on cell growth and cPHB content

The growth of deletion mutants of ydcS (Keio; JWK-1435-1,2) were compared to that of the wild-type strain, BW25113. The cell density of the deletion mutants in early stationary phase was 5–10% less than that of wild-type in LB broth at 37 °C, and ~ 25% less than that of wild-type in minimal medium, 0.4% glucose at 37 °C (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Growth curves of wild-type (BW25113) and deletion mutants (JWK1435-1,2): Culture conditions: M9 medium containing 0.4% glucose, 5mM MgSO4, 0.1mM CaCl2 at 37°C with shaking at 280rpm. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm.

The concentrations of cPHB in late log-phase cells of the wild-type parent strain (BW25113) and the ydcS deletion mutant (JWK-1435-1) were determined by chemical assay. Dried cells of the ydcS deletion mutant contained ~ 25% less cPHB/mg dry wt. as dried cells of the parent strain (Table 1). There was no discernible difference in cPHB/mg protein of the cytoplasms or inner membranes of wild-type and ydcS deletion mutant; however, the outer membranes of the ydcS deletion mutant contained ~30% less cPHB/mg protein than the parent strain (Table 2).

Table 2.

cOHB concentration of whole cells and cell fractions of E. coli BW25113 (wild-type) and JWK1435-1 (ydcS deletion mutant 1) determined by chemical assay. Cytoplasm includes periplasm. Values are the average of 2 determinations.

| E. coli cells | Concentration of cOHB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Cells (µg/mg dry wt.) |

Cytoplasm (µg/mg prot) |

Inner Membrane (µg/mg prot) |

Outer Membrane (µg/mg prot) |

|

| BW25113 (WT) | 5.0 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| JWK1435-1 (DM1) | 3.7 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

Effect of YdcS on synthesis of chloroform-soluble polymers of 3-HB

In addition to cPHB, E. coli cells contain short polymers of R-3HB (~140 residues), known as cPHB, which are complexed to inorganic polyphosphates in the cytoplasmic membranes [12]. cPHB is not covalently bound and hence, unlike cPHB, it can be extracted from the cells with chloroform. The concentration of cPHB in log-phase cells is very low but it increases 50 to 100 fold when the cells are made genetically competent by the Hanahan procedure [12, 21].

To determine whether YdcS may be responsible for synthesis of cPHB or other chloroform-extractable polymers of 3-HB, the concentration of chloroform-soluble 3-HB polymers was determined for equal numbers of log-phase and competent cells of wild-type BW25113 and ydcS deletion mutants (JWK-1435-1,2). The amount of PHB was too low to measure in the log-phase cells, whereas the PHB concentrations in the competent cells of wild-type and ydcS deletion mutants were essentially the same (0.6 ± 0.1 µg/109 cells).

Discussion

Here we find that YdcS, a periplasmic protein of E. coli, exhibits PHB synthase activity. YdcS is a 381 aa protein with a 22 aa signal sequence; the mature protein has a MW of 40 kDa and pI of 6.27. The protein copy number is unknown, but the RNA copy number is 0.1 during log-phase and 0.18 during stationary phase [22]. YdcS is regulated by RpoS, the sigma factor for RNA polymerase which controls the expression of ~50 genes responsible for the adaptations to stress and the survival of stationary-phase cells [23]. It is one of 12 proteins up-regulated as a physiological short-term adaptation to glucose-limitation [24,25].

YdcS is a putative periplasmic-binding protein of an ABC transporter system ydcSTUV [20]. The primary structure of YdcS suggests it may be a member of the α/β hydrolase superfamily of proteins [26] which includes class III PHA oligomerases as well as lipases and esterases [27]. All of the enzymes of this family share a common fold with a catalytic triad which is conserved in the primary sequence in the invariant order nucleophilic residue-acidic residue-histidine, in which the nucleophilic residue can be cysteine, serine or aspartate, the acidic residue can be either aspartic acid or glutamic acid and histidine is strictly conserved [28]. YdcS has a lipase box motif at residues 87–91, GYDLV, containing the aspartate nucleophile. This is unlike PHA synthases and depolymerases whose lipase boxes contain the nucleophiles cysteine or serine [26], and instead resembles the lipase box sequences found in haloalkane dehalogenase superfamily which cleave carbon-halogen bonds in halogenated aliphatic hydrocarbons or epoxide hydrolases which catalyze the hydrolysis of expoxides to the corresponding vicinal diols [29].

Our data indicate that YdcS does not synthesize cPHB involved in channel formation [30] or other chloroform-extractable polymers of 3-HB, however, the ~30% decrease in concentration of cPHB in outer membrane proteins of ydcS deletion mutants is consistent with a role for YdcS in synthesis of cPHB. The concentration of cPHB is higher in outer membrane proteins than in other cell compartments (Table 2). Outer membrane proteins are characteristically amphiphilic; they contain hydrophilic sequences and lack long hydrophobic sequences. These features presumably allow them to escape the cytoplasmic membrane. The addition of cPHB to segments of these proteins in the periplasm may serve to facilitate their insertion into the outer membrane

Figure 3.

CoA-release assays of periplasmic fraction (▽) and purified YdcS-GFP (△). Reaction mixture contained 10 µg periplasmic fraction or 1 µg YdcS-GFP, 1 mM 3-HB-CoA, 10 µg E. coli total phospholipids, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM KHepes, pH 7.5.

Acknowledgements

We thank Douglas Whitten of the Macromolecular Facility of Michigan State University for LC/MS/MS of YdcS, and National BioResource Project (NBRP, Japan) for ASKA His-tagged and GFP-tagged ydcS clones and Keio deletion mutants used in this study. This project was funded by NIH GM054090.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson AJ, Dawes EA. Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol. Rev. 1990;54:450–472. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.450-472.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm BH. Polyester synthases: natural catalysts for plastics. Biochem, J. 2003;376:15–33. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reusch RN. Biological complexes of poly-beta- hydroxybutyrate. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1992;9:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reusch RN. Low molecular weight complexed poly(3-hydroxybutyrate): a dynamic and versatile molecule in vivo. Can. J. Microbiol. 1995;41 Suppl 1:50–54. doi: 10.1139/m95-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das S, Lengweiler UD, Seebach D, Reusch RN. Proof for a nonproteinaceous calcium-selective channel in Escherichia coli by total synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997;94:9075–9079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reusch RN. Polyphosphate/poly-(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate ion channels in cell membranes. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 1999;23:151–182. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-58444-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang R, Reusch RN. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) is associated with specific proteins in the cytoplasm and membranes of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22196–22202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reusch RN, Shabalin O, Crumbaugh A, Wagner R, Schröder O, Wurm R. Posttranslational modification of E. coli histone-like protein H-NS and bovine histones by short-chain poly-(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate (cPHB) FEBS Lett. 2002;527:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xian M, Fuerst MM, Shabalin Y, Reusch RN. Sorting signal of Escherichia coli OmpA is modified by oligo-(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:2660–2666. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theodorou MC, Panagiotidis CA, Panagiotidis CH, Pantazaki AA, Kyriakidis DA. Involvement of the AtoS-AtoC signal transduction system in poly-(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1760:896–906. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitagawa M, Ara T, Arifuzzaman Mj, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Inamoto E, Toyonaga H, Mori H. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Research. 2005;12:291–299. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reusch RN, Hiske TW, Sadoff HL. Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate membrane structure and its relationship to genetic transformability in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1986;168:553–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.553-562.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborn MJ, Gander JE, Paris E, Carson J. Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Isolation and characterization of cytoplasmic and outer membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:3962–3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissbach A, Hurwitz J. The formation of 2-keto-3-deoxyheptonic acid in extracts of Escherichia coli B: I. Identification. J. Biol. Chem. 1959;234:705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nossal NG, Heppel LA. The release of enzymes by osmotic shock from Escherichia coli in exponential phase. J. Biol. Chem. 1966;241:3055–3062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müh U, Sinskey AJ, Kirby DP, Lane WS, Stubbe J. PHA synthase from Chromatium vinosum: cysteine 149 is involved in covalent catalysis. Biochem. 1999;38:826–837. doi: 10.1021/bi9818319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karr DB, Waters JK, Emerich DW. Analysis of poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate in Rhizobium japonicum bacteroids by ion-exclusion chromatography and UV detection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983;46:1339–1344. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.6.1339-1344.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen ON, Wilm M, Shevchenko A, Mann M. Peptide sequencing of 2-DE gel-isolated proteins by nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999;112:571–588. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saurin W, Hofnung M, Dassa EJ. Getting in or out: early segregation between importers and exporters in the evolution of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Mol. Evol. 1999;48:22–41. doi: 10.1007/pl00006442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan DJ. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;166:558–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selinger DW, Cheung KJ, Mei R, Johansson EM, Richmond CS, Blattner FR, Lockhart DJ, Church GM. RNA expression analysis using a 30 base pair resolution Escherichia coli genome array. Nat.. Biotechnol. 2000;18:1262–1268. doi: 10.1038/82367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somalinga R, Vijayakumar V, Kirchhof MG, Patten CL, Schellhorn HE. RpoS-Regulated Genes of Escherichia coli Identified by Random lacZ Fusion Mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:8499–8507. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8499-8507.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wick LM, Quadroni M, Egli T. Short- and long-term changes in proteome composition and kinetic properties in a culture of Escherichia coli during transition from glucose-excess to glucose-limited growth conditions in continuous culture and vice versa. Environ Microbiol. 2001;3:588–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franchini AG, Egli T. Global gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12 during short-term and long-term adaptation to glucose-limited continuous culture conditions. Microbiol. 2006;15:2111–2127. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28939-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wahab HA, Khairudin A, Samian MR, Najimudin N. Sequence analysis and structure prediction of type II Pseudomonas sp. USM 4–55 PHA synthase and an insight into its catalytic mechanism. BMC Struct. Biol. 2006;6:6–23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia Y, Kappock TJ, Frick T, Sinskey AJ, Stubbe J. Lipases provide a new mechanistic model for polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthases: characterization of the functional residues in Chromatium vinosum PHB synthase. Biochem. 2000;39:3927–3936. doi: 10.1021/bi9928086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ollis DL, Cheah E, Cygler M, Dijkstra B, Frolow F, Franken SM, Harel M, Remington SJ, Silman I, Schrag J, Sussman JL, Verschueren KHG, Goldman A. The alpha/beta hydrolase fold. Protein Eng. 1992;5:197–211. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Loo B, Kingma J, Armand M, Wubbolts MG, Janssen DB. Diversity and biocatalytic potential of epoxide hydrolases identified by genome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:2905–2917. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2905-2917.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reusch RN, Huang R, Bramble LL. Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate/polyphosphate complexes form voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in the plasma membranes of Escherichia coli. Biophys. J. 1995;69:754–766. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79958-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]