Abstract

VIDA is a new virus database that organizes open reading frames (ORFs) from partial and complete genomic sequences from animal viruses. Currently VIDA includes all sequences from GenBank for Herpesviridae, Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae. The ORFs are organized into homologous protein families, which are identified on the basis of sequence similarity relationships. Conserved sequence regions of potential functional importance are identified and can be retrieved as sequence alignments. We use a controlled taxonomical and functional classification for all the proteins and protein families in the database. When available, protein structures that are related to the families have also been included. The database is available for online search and sequence information retrieval at http://www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/bsm/virus_database/VIDA.html.

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge of complete virus genome sequences has helped biologists develop a fundamental understanding of viral replication and host–pathogen interactions. However, the consistent analysis of viral proteins in the absence of many of today’s bioinformatics approaches has resulted in the level of organization and annotation of viral genomic sequences being inferior compared to other genome databases. The number of available viral genomic sequences continues to grow. For example, in the herpesvirus family the number of complete genomes has increased from 10 to 26 in the last 5 years, and partial genomic sequences encoding a range of open reading frames (ORFs) exist for at least another 25 herpesviruses. As a great deal of heterogeneity and redundancy exist for viral sequences in the primary databases, there is a need to create databases that facilitate the retrieval of relevant information. Existing virus sequence databases are mainly focused on the visualization and interpretation of complete virus genomes (1–3) or the detailed study of particular virus proteins (4).

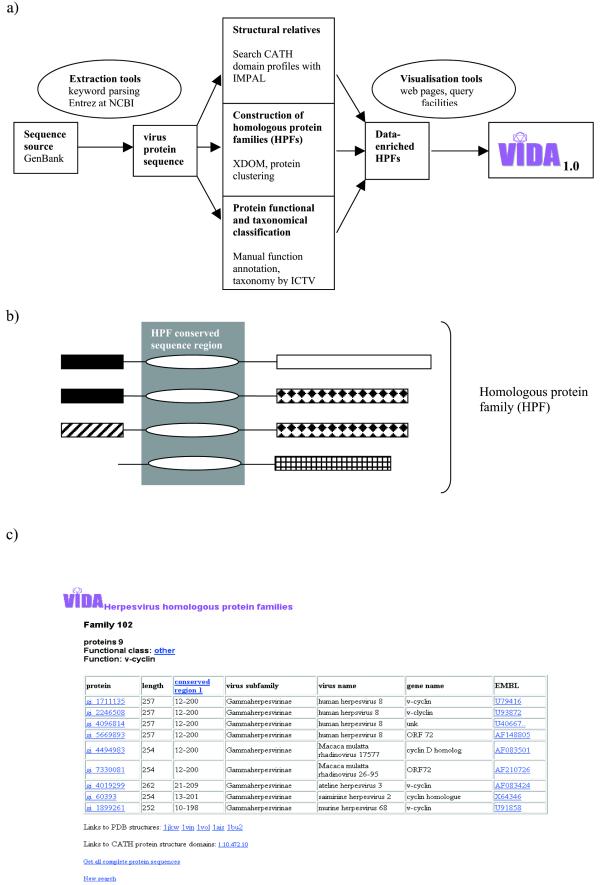

We have developed a virus database, VIDA, that organizes information on viral ORFs from complete or partial genomic sequences derived from GenBank (5). The database is focused on animal viruses. It contains up to date compilations of viral-specific protein families, which are identified on the basis of sequence similarity relationships between the ORFs. The approach resembles that used by Montague and Hutchison (6) to construct clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) from protein sequences from 13 herpesvirus complete genomes. However, in VIDA, homologous protein families include both orthologous and paralogous sequences as long as they have significant sequence similarity. The families within VIDA are automatically derived for all ORFs from a given virus family, e.g. herpesviruses. Viral ORFs can exhibit high mutation rates and can diverge quickly. Therefore the identification of conserved sequence regions is a valuable tool in identifying functionally important protein regions and to cross-compare different virus genomes. For each protein family entry in VIDA it is possible to obtain alignments of the conserved regions. Additionally, complete protein sequences can be retrieved as single FASTA format files for easy import into other sequence analysis programs. Links to the original genomic entries and information on protein folds, when available, are also provided. A simple virus-specific functional classification has been developed and used to classify the protein families into typical viral processes. The procedures used to organize the virus protein sequences are shown in Figure 1a. In addition to keyword searches, facilities exist to browse the protein families in a controlled way using the virus name or functional class. The present release of VIDA includes all ORFs from the Herpesviridae family and the order Nidovirales, containing the Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae families (7).

Figure 1.

(a) Flow of procedures used to build VIDA 1.0. Virus protein sequences are retrieved for a defined virus family from GenBank and fields are parsed [see also (c)]. Three separate procedures are performed on the protein sequences, namely, identification of structural relatives (CATH domain profiles), construction of HPFs and protein functional annotation and virus taxonomical classification. These data are all mapped and visualised through web pages in a searchable format. (b) Schematic representation of an HPF with four protein members and one conserved sequence region, the rectangles and ovals with same filling represent regions of sequence similarity. Initially all sequence domains are identified using XDOM with default parameters. Our own C programs are then used to compile the HPFs based on the fact that all proteins in an HPF must share at least one region of conserved sequence similarity and the HPF should be as large as possible and not fragmented. (c) Example of homologous protein family table showing the virus proteins included in family 102. Within the table information is provided on the proposed function and functional class of the HPF. In addition the proteins, virus family, virus names and GenBank derived gene names are provided. Links to the HPF conserved sequence region, proteins in FASTA format and source EMBL record are included. Where available links to structural PDB files and CATH domains are also provided.

CONSTRUCTION AND ORGANIZATION OF THE VIRUS DATABASE (VIDA)

Homologous protein families (HPFs)

VIDA uses GenBank files as a source for virus sequences. Files relating to a virus family are downloaded using keywords (for example Herpesviridae) and a number of fields within the GenBank files are parsed out into sub-files. The parsed fields include the GenBank accession number, sequence length, protein GenBank identifiers (GI numbers), sequence source, gene name and gene product. Partial ORFs in GenBank entries are not parsed into the database, which should only contain complete protein sequences. The protein sequences are further filtered to eliminate 100% redundancy and a list of synonymous GIs created for further reference.

Analysis of related proteins is often greatly enhanced by determining the sequence relationships between the individual proteins. This has the power of identifying regions of sequence similarity and of possible functional conservation. The clustering of homologous sequences therefore provides a rational way of organizing protein sequence data. We built up HPFs in two steps. Initially we identified all regions of sequence similarity in the viral ORFs using the XDOM program with default parameters (8). XDOM is based on BLASTP (9) and had previously been used to identify regions of protein sequence similarity in different complete genomes from bacteria, archaea and eukarya (10). We then used our own C program (PSCbuilder) to build up families of proteins, by taking those proteins that share at least one region of sequence similarity. These are defined as HPFs (Fig. 1b). PSCbuilder constructs families that contain as many protein members as possible, which prevents fragmentation of HPFs into subgroups of proteins and therefore maximizes the amount of functionally important information content embedded within the protein families. While most of the HPFs are defined by one region of sequence similarity others, for example the herpesvirus DNA-dependent DNA polymerase, contain several consecutive sequence similarity regions which are present in all the proteins.

Protein structure

Whenever possible, we have included information on known viral protein structures or structures homologous to viral proteins and mapped them onto homologous protein families. This was achieved by searching all viral proteins against a library of structural domain profiles derived from the CATH database (11) using PSI-BLAST (12). The search was performed with the IMPALA software (13). In both these programs the expectation value (E) threshold was set at 0.0005. We could detect structural relatives for ~8% of the homologous protein families. Links are available as the original PDB entries and/or CATH domain entries.

Functional annotation

We have developed a simple functional classification schema to assign proteins to broad functional classes that reflect typical virus processes. So far we have defined the following classes: DNA replication, RNA replication, Virus structural proteins, Glycoproteins, Nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism, Transcription and Others. The different homologous protein families have been manually assigned to these classes and given a short functional description. We have mostly used the original ORF annotations in the GenBank files to assign the protein to a functional group.

Virus taxonomy

We have used the nomenclature used in The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (14) to name the species, genus and subfamilies of each of the viruses used in the database. In some cases we needed to create synonymous lists to accommodate the different names used in GenBank entries for the same virus. This enables the users to perform searches using any of the synonymous names while maintaining consistency within the database. In addition, the search by virus name is facilitated by a list of standard virus names from which to choose. Taxon and virus name are integral parts of the HPF tables making it easy for users to assess the virus phylogenetic distribution of the family.

CONTENT OF CURRENT RELEASE

VIDA 1.0 contains entries for the Herpesviridae family and the order Nidovirales (Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae). Herpesviruses have large double stranded DNA genomes, with between 80 and 220 ORFs per genome, while Nidovirales are single stranded RNA viruses that encode 8–12 ORFs. In VIDA 1.0 there are 812 HPF entries (Table 1). The entries are presented in the form of tables that include information on the length of the proteins, start and end of conserved sequence regions, virus taxa and name, gene name and links to EMBL entries (Fig. 1c). In addition it is possible to retrieve the protein sequences, DNA sequences, alignment of conserved sequence regions and follow links to structural folds (CATH and PDB entries) and functional class.

Table 1. VIDA 1.0 summary information.

| Virus family |

Complete genomes |

Protein entriesa |

HPFsb |

Structural relatives |

| Herpesviridae | 26 | 4196 | 756 | 61 |

| Coronaviridae | 7 | 491 | 42 | 3 |

| Arteriviridae | 7 | 790 | 14 | 1 |

| Total | 40 | 5477 | 812 | 65 |

aTotal number of complete protein sequence entries.

bHomologous protein families.

DATABASE ACCESS

VIDA 1.0 is entered through an initial web page (http://www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/bsm/virus_database/VIDA.html) that lists the current virus families within the database. Links to the complete genome sequences of viruses within the family are provided as well as links to other virus sites and general sequence analysis resources. For each virus family, links through the ‘Search homologous protein families’ enable the searching of the HPFs by virus name, function (for example DNA polymerase), GI code (GenBank protein entry) or free text (for example UL6, ORF 20). It is also possible to retrieve all HPFs belonging to a defined functional class. The hits are presented as a list of HPFs with a short description covering number of protein members and function. Following the links results in the specific HPF tables (Fig. 1c).

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

VIDA has been developed to organize viral sequence and annotations from the main sequence database repositories. The sequences are extracted from different animal virus families. Non-redundant complete ORF sequences derived from GenBank are automatically clustered into homologous protein families. The protein families are a rich source of information for functional and evolutionary studies and the alignments of the conserved sequence regions facilitate the direct study of important conserved amino acids or construction of sequence profiles. VIDA 1.0 is particularly relevant to the herpesvirus, coronavirus and arterivirus communities. It will be updated with each new GenBank release and we are committed to incorporate other animal virus families. Its functionality will be gradually improved for example, by providing sequence-based search programs. We also plan to move from the present flat file format to Oracle relational database format. Functional annotation should benefit from contributions and feedback from other experts in the field, which we strongly encourage.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the Medical Research Council for grants to D.L., N.M., C.A.O. and P.K. and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council for grants to M.M.A., F.M.G.P. and A.J.S.

References

- 1.Tamames J. and Tramontano,A. (2000) DANTE: A workbench for sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci., 25, 402–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiscock D. and Upton,C (2000) Viral Genome DataBase: storing and analyzing genes and proteins from complete viral genomes. Bioinformatics, 16, 484–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler D.L., Chappey,C., Lash,A.E., Leipe,D.D., Madden,T.L., Schuler,G.D.,Tatusova,T.A. and Rapp,B.A. (2000) Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 10–14. Updated article in this issue: Nucleic Acids Res. (2001), 29, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shafer R.W., Jung,D.R., Betts,B.J., Xi,Y. and Gonzales,M.J. (2000) Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 346–348. Updated article in this issue: Nucleic Acids Res. (2001), 29, 296–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson D.A., Karsch-Mizrachi,I., Lipman,D.J., Ostell,J., Rapp,B.A. and Wheeler,L.(2000) GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 15–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montague M.G. and Hutchison,C.A.,III (2000) Gene content phylogeny of herpesviruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5334–5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snijder E.J. and Meulenberg,J.J.M. (1998) The molecular biology of arteriviruses. J. Gen. Virol., 79, 961–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouzy J., Eugene,P., Greene,E.A., Khan,D. and Corpet,F. (1997) XDOM, a graphical tool to analyse domain arrangements in any set of protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci., 13, 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altschul S.F., Gish,W., Miller,W., Myers,E.W. and Lipman,D.J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouzy J., Corpet,F. and Kahn,D. (1999) Whole genome protein domain analysis using a new method for domain clustering. Comput. Chem., 23, 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearl F.M.G., Lee,D., Bray,J.E., Sillitoe,I, Todd,A.E., Harrison,A.P., Thomton,J.M. and Orengo,C.A. (2000) Using the CATH domain database to assign structures and functions to the genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 277–282. Updated article in this issue: Nucleic Acids Res. (2001), 29, 223–227.10592246 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schäffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3398–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schäffer A.A., Wolf,Y.l., Ponting,C.P., Koonin,E.V., Aravind,L. and Altschul,S.F.(1999) IMPALA: matching a protein sequence against a collection of PSI-BLAST-constructed position-specific score matrices. Bioinformatics, 15, 1000–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Regenmortel M.H.V., Fauquet,C.M., Bishop,D.H.L., Carstens,E.B., Estes,M.K., Lemon,S.M., Maniloff,J., Mayo,M.A., MeGeoch,D.J., Pringle,C.R. and Wickner,R.B.(2000) Virus taxonomy: The Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. The Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, p. 1167.