Abstract

Since the first clinical orthotopic liver transplant was performed 13 years ago, approximately 275 patients have undergone this procedure. The Denver series constitutes about 40% of this total experience. In our series, the overall 1-year survival has been 29%; the longest survivor is now 62/3 years posttransplantation. Most of the early deaths have been caused by technical complications, frequently related to difficulties in establishing and maintaining adequate biliary drainage. The late deaths have been from a variety of causes, including recurrent tumor, hepatitis, bile duct obstruction, and chronic rejection.

Favorable indications for liver transplantation include biliary atresia, chronic aggressive hepatitis, inborn errors of metabolism, and certain other benign hepatic diseases. Alcoholic cirrhosis is a less favorable indication and primary hepatic malignancy is a relative contraindication. The immunologic criteria for donor-recipient selection are much less rigid than for renal transplantation.

Biliary reconstruction is the principal technical problem encountered with orthotopic liver transplantation. Guidelines for the establishment of biliary drainage, its evaluation, and the management of postoperative biliary complications are discussed.

The first orthotopic liver transplant in man was performed on March 1, 1963 at the University of Colorado [1]. Since then, approximately 275 patients have been treated with this procedure throughout the world. The Denver series now includes 114 patients or about 40% of the total experience. The second most active group in the field has been composed of personnel at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, and at King's College Hospital, London. The British inter-university effort has involved the fruitful collabo- ration of the surgeon. Professor Roy Calne, and the gastroenterologist, Professor Roger Williams, and has resulted in approximately 50 orthotopic liver transplantations. The numerous and important contributions [2–4] from the United Kingdom group should be perused by anyone deeply interested in this subject.

Six months ago, we described in detail the results in our first 93 cases [5], In this article, we will discuss our present views regarding liver transplantation based largely on the conclusions of that report, emphasizing our results with the procedure, the question of candidacy for liver transplantation, and certain technical problems that have been encountered, particularly the problem of biliary reconstruction.

Results of Liver Transplantation: University of Colorado Series

Of the 114 patients in the University of Colorado series, 103 were transplanted a year or more ago. Thirty of them, or 29%, have survived for at least 1 year after liver replacement (Table 1). In recent years, the 1-year survival figures have been generally somewhat better, fluctuating in the 25 to 45% range.

Table 1.

Survival after liver transplantation at the University of Colorado

| No. | Lived |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 2 years | 3 years | 4 years | 5 years | Alive now | ||

| 1963–1966 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1967 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1968 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1969 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 0 |

| 1970 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1971 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 1972 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1973 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1974 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 1975 | 8 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| 103 | 30 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 15 | |

Only patients at risk for 1 year are included.

Died after 5 11/12 years.

Alive 6 2/3 years.

If this heavy early mortality were to continue after the first year, there would be significant cause to question the validity of the procedure. Fortunately, most of the patients who reach the 1-year mark continue to do well thereafter. For example, half of all our 1-year survivors are still alive. A total of 15 patients have reached the 2-year mark, 8 have reached 3 years, and 4 are 5-year survivors (Table 1). The longest survivor in our series (and in the world) is now 62/3 years post-transplantation. She is living at home, attending school, and has normal liver function. Two other 5-year survivors are also entirely well, but the fourth one died a few days short of the 6-year mark of chronic rejection and partial biliary obstruction.

The causes of death after 1 year are given in Table 2. In retrospect, at least some of these late deaths might have been avoided, either by better patient selection (in the case of recurrent tumor) or by improved management, particularly of biliary tract problems.

Table 2.

Present status of 30 one-year survivors of liver transplantation

| Alive 15/30 — | 12 months to 80 months |

| Dead 15/30 — | 12 months to 71 months |

| Recurrent cancer—4 | |

| Chronic rejection—5 | |

| Chronic hepatitis—2 | |

| Bile duct obstruction—2 | |

| Other infections—2 |

Selection of Candidates for Liver Transplantation

Influence of Age

Not surprisingly, younger patients have had a better prognosis after liver transplantation than older ones; for patients over 40 years of age, the 1-year survival has been less than 10%. The much increased mortality in the older recipients has largely been the consequence of pulmonary or other infectious complications, problems with maintaining adequate nutrition, or neurologic complications. We believe that candidacy for this formidable undertaking generally should be limited to those under 45 years of age, and that potential recipients toward the upper end of this spectrum should be carefully evaluated preoperatively.

Influence of the Original Hepatic Disease

Primary Hepatic Malignancies

A number of the early recipients of liver homografts were transplanted for nonresectable hepatic malignancies, such as hepatoma, cholangiocarcinoma, or hemangioendothelial sarcoma. Of our 12 patients in this category, 7 died soon after transplantation of complications not related to their malignancy. The other 5 patients, however, all developed tumor recurrence and died from 87 to 432 days after transplantation. Widespread metastases were found at autopsy, and, interestingly, the homograft livers almost always contained tumor.

Because of this proclivity to develop tumor recurrence after transplantation, we view patients with large, nonresectable primary hepatic malignancies as highly questionable candidates for liver replacement. Exceptions to this policy have been made if a tumor is an incidental finding in a liver afflicted with another disease. For example, one of our recipients with biliary atresia also had a small hepatoma in the excised specimen. Not only has she had no evidence of tumor recurrence, but she is our longest survivor after liver transplantation.

Initially we thought the so-called Klatskin tumors [6], duct cell carcinomas arising at the bifurcation of the hepatic ducts, might be an exceptionally good indication for liver transplantation. These tumors, because of their strategic location, usually become symptomatic while still quite small and usually kill by obstruction rather than by widespread disease. Four patients with this malignancy have been treated by liver replacement. Two died early after operation. The other 2 patients survived 2 years postoperatively; 1 died at that time of recurrent tumor in, his transplanted liver, and the other is alive and clinically free of recurrent malignancy. Although the long-term prognosis in such cases is still in doubt, further trials in younger patients are certainly warranted.

Biliary Atresia

Children with biliary atresia are generally good candidates for liver transplantation. These patients usually enjoy relatively good health until late in the course of the disease and their livers often retain adequate synthetic function. In individual cases, however, it may prove difficult or even impossible to revascularize the homgoraft livers, either because of congenital anomalies of the hepatic blood supply, which are not uncommon in patients with biliary atresia, or because of technical problems posed by the small size of the vessels. The latter difficulties have largely been overcome by employing microsurgical techniques in reconstructing the hepatic blood supply.

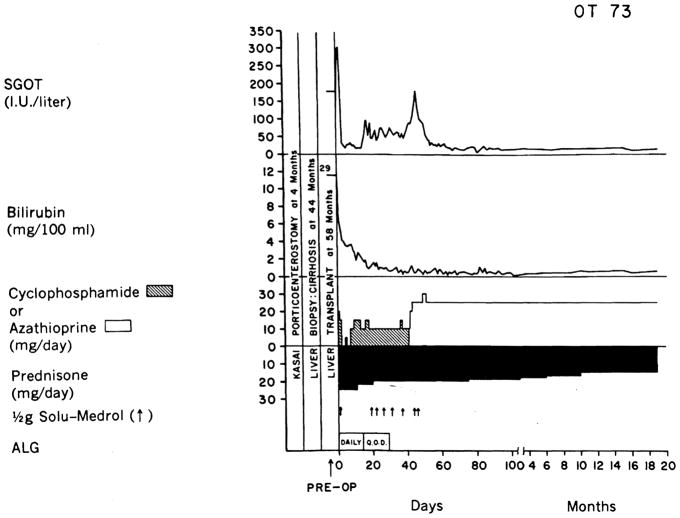

Several of our patients transplanted for biliary atresia have had prior Kasai porticoenterostomy procedures. The previous operative intervention has not precluded successful transplantation [7], and in several cases the Kasai procedure has successsfully "bought time" for the patient, thus lengthening the period of potential candidacy for transplantation (Figure 1). This is obviously of particular importance in these youngsters for whom potential donors are few and far between.

Fig. 1.

The course of a child who had a failed Kasai operation but who ultimately was effectively treated with liver replacement. (From ref. 7 with permission.)

Alcoholic Cirrhosis

The results of transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis have been much less satisfactory. Of 11 such patients transplanted so far, only 1, a former professional football player, has achieved long-term survival. Another patient is alive less than 2 months after the procedure. If the patient has repudiated the use of alcohol, there should be no intrinsic contraindication to his candidacy. In practice, the uncertain course of this disease has frequently resulted in procrastination in referring patients for the procedure. By the time of referral, one or more complications has usually supervened. Most commonly, gastrointestinal bleeding, pneumonitis or other infectious complications, or hepatic encephalopathy are present, thereby severely jeopardizing the chances for recovery. Improvement in the results after transplantation in this group of candidates will require that these patients be referred for transplantation before these complications arise.

Chronic Aggressive Hepatitis

Postnecrotic cirrhosis or chronic aggressive hepatitis are favorable indications for transplantation. Patients with these diseases are usually younger than those with alcoholic cirrhosis and the downhill course of their disease is generally more predictable. If the hepatitis B antigen is not present preoperatively, the recipient does not seem to be at significant risk of developing recurrent hepatitis postoperatively. When antigenemia predates transplantation, antigen-positive hepatitis postoperatively may prove to be a major threat. Indeed, one of our patients who was transplanted for this indication developed acute antigen-positive hepatitis postoperatively, which progressed to chronic aggressive hepatitis from which she eventually died [8]. Retrospective analysis of serum samples during the early postoperative period showed that trace amounts of the antigen were still present and probably caused infection of the homograft liver. Two patients with antigen-positive hepatitis treated subsequently have received high-titer anti-HBs Ag antiserum intra- and postoperatively. This therapy appeared to be successful in eliminating the residual serum antigen remaining after removal of the infected liver. Unfortunately, both patients died early after operation, 3 and 7 weeks post-operatively, before clinical hepatitis could be expected to appear. Thus, the effectiveness of antiserum therapy in preventing the subsequent occurrence of hepatitis will be determined only by further trials.

Inborn Errors of Metabolism

Our best results with liver transplantation have been in patients with hepatic-based inborn errors of metabolism. We have treated 3 such diseases: Wilson's disease, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, and tyrosinemia. In addition, Daloze, Corman and their associates in Montreal [9] have successfully transplanted a patient with Niemann-Pick disease.

In Wilson's disease, there is progressive accumulation of copper in the body. The characteristic Kayser-Fleischer rings are an external manifestation of this, representing discoloration of the corneas by the metal deposits. More importantly, deposition of copper in the liver and brain may cause subsequent degenerative changes. We have treated 2 children for this disorder [10, 11]. Both survived for 5 years after transplantation; one is alive and entirely well, but the other died of chronic rejection and partial biliary obstruction unrelieved by late reoperation. Metabolic studies in these patients showed that the copper-containing ceruloplasmin, which was low or virtually absent preoperatively, became normal postoperatively. There was a prolonged cupriuresis postoperatively, which reduced the tremendously elevated total body copper content. Neither of the homografts showed any tendency to reaccumulate the metal. One of the patients had severe neurologic impairment preoperatively which gradually improved after transplantation, becoming normal over the next 3 years.

Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency is a hereditary disease which predisposes to congenital infantile cirrhosis [12] and occasionally adult cirrhosis, as well as pulmonary emphysema of early onset in adults. The homozygous PiZZ phenotype is not terribly rare; its incidence is estimated to be about 1 in 2,500 live births. Approximately 20 to 30% of children who have this phenotype will develop cirrhosis [12].

In November, 1973, we transplanted a 16-year-old girl with cirrhosis caused by alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, PiZZ phenotype [13]. Postoperatively, she developed normal levels of alpha1-antitrypsin which had the donor phenotype, PiMM (Table 3). Two years after transplantation her graft failed from chronic rejection. A second transplantation was performed, the donor for which by coincidence had the heterozygous PiMZ phenotype and a correspondingly reduced serum alpha1-antitrypsin concentration (heterozygotes, however, have no predilection to develop liver disease). Following retransplantation the recipient again adopted the donor's phenotype, this time PiMZ (Table 3). Unfortunately, the patient died a month later of pulmonary infection, but the validity of the metabolic correction by liver transplantation was established.

Table 3.

Serum alpha1-antitrypsin concentration and phenotypes before and after liver transplantation

| Pretransplant | First donor | Post-transplant |

Second donor | After retransplant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 months | 27 months | |||||

| Phenotype | ZZ | MM | MM | MM | MZ | MZ |

| Enzyme Concentration (mg%) (normal 140–470) | 55 | — | 256 | 264 | 176 | 270 |

Daloze, Corman, and their associates [9] have treated a 2-year-old child with Niemann-Pick disease. In this disorder, deposits of sphingomyelin within the liver cause hepatic failure. After transplantation, the homograft liver showed no tendency to reaccumulate sphingomyelin, and sphingomyelinase, the deficient enzyme, could be found in normal concentrations in the blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, and the graft itself. Unfortunately, there was severe neurologic impairment preoperatively which did not improve after transplantation and the child died of respiratory complications 2 years later.

The fourth inborn error of metabolism which has been treated by liver transplantation is tyrosinemia. Two months ago we transplanted a 10-year-old child with this disorder who also had a multifocal hepatoma within her severely cirrhotic liver. Postoperatively, the serum and urine tyrosine concentrations rapidly became normal and the urinary excretion of p-hydroxyphenyl pyruvic acid products gradually declined. These findings suggest that this disorder was corrected by transplantation; further metabolic studies are now in progress.

Other Benign Hepatic Diseases

Prolonged survival has been achieved after liver replacement in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and the Budd-Chiari syndrome [14]. However, we have not yet successfully treated patients with acute liver failure from fulminant hepatitis or other toxic agents, largely because of the logistic problems in obtaining an appropriate cadaveric organ during the brief time span in which such patients are satisfactory candidates for transplantation.

Criteria for Donor-Recipient Selection

Since no artificial support system comparable to hemodialysis is available to potential recipients of liver transplants, their period of candidacy is necessarily much shorter than that of patients with end-stage renal disease. Therefore, a relaxation of criteria for donor-recipient selection is necessary if they are to be treated at all. Indeed, if the pace of deterioration of the recipient warrants doing so, all ordinary immunologic restrictions may be ignored and an ABO-incompatible or crossmatch-positive organ inserted. Under less pressing circumstances, of course, the guidelines described below are observed.

ABO Compatibility

The rules for ABO matching of donor to recipient are identical to those used for transplantation of other organs, such as the kidney. If these barriers are violated in renal transplantation, hyperacute rejection of the organ is the usual although not invariable consequence. This does not appear to be the case after liver transplantation, since 7 of our patients have received such ABO-incompatible organs without any evidence of hyperacute rejection. However, it is not yet clear whether these organs may be more susceptible to late rejection than ABO-compatible ones.

Cytotoxic Antibody Crossmatch

Hyperacute rejection of renal homografts is also an extremely common occurrence if the recipient possesses preformed cytotoxic antibodies against donor cells. Again, the liver is quite resistant to this immunologic complication; the fate of hepatic homografts placed in such an immunologically hostile environment does not seem to be any different than in crossmatch-negative cases.

HL-A Typing

Although HL-A typing is routinely performed, the results are not used to guide the selection of donor-recipient pairs. As a consequence of this policy, most of the HL-A matches have been poor ones (Table 4). With such a skewed spectrum of histocompatibility, conclusions about the predictive validity of the technique cannot be drawn. Clearly, there is no definable correlation between the quality of match and survival in this limited series (Table 4).

Table 4.

HL-A typing of primary hepatic grafts in 103 cases

| Match* | No. | Survival I year |

|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 1† |

| B | 3 | (33%) |

| C | 15 | 3(20%) |

| D | 27 | 5(19%) |

| E | 44 | 16(36%) |

| F | 6 | 1(17%) |

| Not done | 7 |

1(14%) |

| Total | 103 | 28 (29%) |

A match, HL-A identity between recipient and donor; B match, compatibility between donor and recipient, but fewer antigens determined in the donor; C match, one antigen incompatible; D match, two antigens incompatible; E match, three or four antigens incompatible; F match, ABO violation or positive crossmatch to cytotoxic antibodies.

Retransplanted after 68 days with C-match graft. Thus, the I-year survival was due mainly to the second, less well matched organ.

Techniques of Orthotopic Liver Transplantation

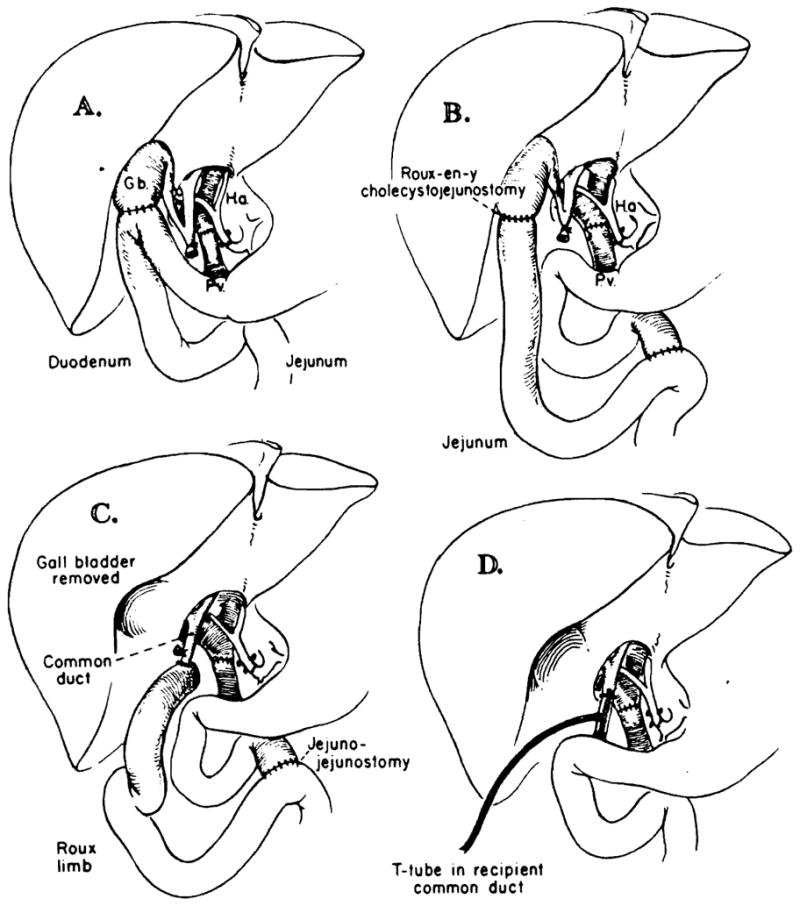

The vascular reconstruction of the orthotopic liver homograft has largely become standardized. The graft vena cava is anastomosed to the analogous host vessels above and below the liver. The portal vein of the graft is anastomosed end-to-end to the host portal vein, and the hepatic artery is usually revascularized with the common hepatic artery of the recipient (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

A–D. Techniques of biliary duct reconstruction used for most of the transplantation recipients. A. Cholecystoduodenostomy. B. Cholecysto-jejunostomy. C. Choledochojejunostomy after removal of gallbladder. D. Choledochocholedochostomy. Note that the T-tube is placed, if possible, in recipient common duct. (From ref. 5 with permission.)

Most of the technical problems with this procedure have arisen from failure to maintain satisfactory biliary drainage. Until 1973, biliary reconstruction was usually with cholecystoduodenostomy (Figure 2A). The weak link of this technique is the cystic duct, which becomes obstructed in about one-third of the cases in which the gallbladder is used for anastomosis. In the first few cases in which this occurred, the correct diagnosis was not made until autopsy. Subsequently, several cases were diagnosed during life by operative cholangiography, but reoperation was still usually too late. In 1973, a policy of performing transhepatic cholangiography whenever recurrent jaundice appeared was adopted. For this study, the very thin needle developed in Chiba, Japan, was used. This technique proved to be quite safe and immensely helpful.

At about the same time, an appreciation of the role of hepatic sepsis in these cases led to the adoption of Roux-en-y biliary drainage to avoid gastrointestinal contamination of the biliary system. The strategy that evolved was to perform cholecysto-Roux-en-y-jeju-nostomy (Figure 2B) as the primary reconstruction. If jaundice reappeared and transhepatic cholangiography confirmed cystic duct obstruction, the gallbladder was removed and a choledochojejunostomy created (Figure 2C). Alternative techniques which share the advantage of placing the biliary system out of the direct continuity with the gastrointestinal tract include choledochocholedochostomy with T-tube drainage (Figure 2D) and primary choledochojejunostomy.

It is apparent that no one technique of biliary reconstruction will be satisfactory for all patients; each case must be individualized. Certain principles of reconstruction, however, have emerged. Ideally, the biliary reconstruction should avoid using the cystic duct with its inherently high risk of obstruction. Secondly, the liver should be protected from the bacterially contaminated gastrointestinal contents either with a defunctionalized Roux-en-y limb of jejunum or by the sphincter of Oddi. Thirdly, radiographic visualization of the biliary tree, either by tube cholangiography or by the transhepatic approach, must be obtained whenever jaundice reappears after transplantation. Finally, if obstruction is detected, prompt reoperation is vital.

Future Prospects

The procedure of orthotopic liver transplantation is a formidable one, particularly when the patient has significant portal hypertension and a major coagulopathy. Moreover, problems with biliary reconstruction have plagued this venture during its infancy and, indeed, continue to do so. The necessary preoccupation with the technical requirements of liver replacement has obscured the fact that rejection has been much less of a problem [5] than after cadaveric renal homotransplantation. Yet only by the precise management of technical details will the benefits afforded by this immunologic advantage be accrued. Despite this advantage, liver homografts will still be lost from rejection. Rather than pursuing aggressive immunosuppression in an attempt to prolong graft survival, investigators may have to show a greater willingness to accept the need for retransplantation, despite the obvious technical obstacles.

Acknowledgments

Supported by research grants MRIS 8118-01 and 7227-01 from the Veterans Administration; by United States Public Health Service Grants AM-I7260 and AM-07772; and by Grants RR-00051 and RR-00069 from the General Clinical Research Centers Program of the Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Starzl TE, Putnam CW. Experience in Hepatic Transplantation. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calne RY, Williams R, Dawson JL, Ansell ID, Evans DE, Flute PT, Herbertson PM, Joysey V, Keates GHW, Knill-Jones RP, Masow SA, Millard PR, Pena JR, Pentlow BD, Salaman JR, Sells RA, Cullum PA. Liver transplantation in man. II. A report of two orthotopic liver transplants in adults recipients. Br Med J. 1968;4:541. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams R, Smith M, Shilkin KB, Herbertson B, Joysey V, Calne RY. Liver transplantation in man; the frequency of rejection, biliary tract complications, and recurrence of malignancy based on an analysis of 26 cases. Gastroenterology. 1973;64:1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calne RY. Clinical and experimental liver grafting. Guys Hosp Rep. 1974;123:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starzl TE, Porter KA, Putnam CW, Schroter GPJ, Halgrimson CG, Weil R, III, Hoelseher M, Redi HAS. Orthotopic liver transplantation in ninety-three patients. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1976;142:487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klatskin G. Adenocarcinoma of the hepatic duct at its bifurcation within the porta hepatis: an unusual tumor with distinctive clinical and pathological features. Am J Med. 1965;38:241. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(65)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starzl TE, Porter KA, Putnam CW, Beart RW, Halgrimson CG, Gadir AFA. Liver replacement in children. Proceedings of the Josiah Macy, Jr., Foundation International Conference on Liver Disease in Infancy and Childhood; June 26–28, 1975; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corman JL, Putnam CW, Iwatsuki S, Redeker AG, Porter KA, Peters RL, Schroter G, Starzl TE. Liver homotransplantation for chronic aggressive hepatitis, Australia antigen positive. Gastroenterology. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daloze P, Corman J, Bloch P, Delvin EE, Glorieux FH. Enzyme replacement in Niemann-Pick disease by liver homotransplantation. Transplant Proc. 1975;7:607. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DuBois RS, Giles G, Rodgerson DO, Lilly J, Martineau G, Halgrimson CG, Schroter G, Starzl TE, Sternlieb I, Sheinberg IH. Orthotopic liver transplantation for Wilson's disease. Lancet. 1971;1:505. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groth CG, DuBois RS, Corman J, Gustafsson A, Iwatsukis S, Rodgerson DO, Halgrimson CG, Starzl TE. Metabolic effects of hepatic replacement in Wilson's disease. Transplant Proc. 1973;5:829. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp HL. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Hosp Prac. 1971;6:83. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Putnam CW, Porter KA, Peters RL, Ashcavai M, Redeker AG, Starzl TE. Liver replacement for alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Surgery. (in press) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putnam CW, Porter KA, Weil R, Reid HAS, Starzl TE. Liver transplantation for the Budd-Chiari syndrome. JAMA. 1976;236:1142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]