Abstract

In humans, septal defects are among the most prevalent congenital heart diseases, but their cellular and molecular origins are not fully understood. We report that transcription factor Tbx5 is present in a subpopulation of endocardial cells and that its deletion therein results in fully penetrant, dose-dependent atrial septal defects in mice. Increased apoptosis of endocardial cells lacking Tbx5, as well as neighboring TBX5-positive myocardial cells of the atrial septum through activation of endocardial NOS (Nos3), is the underlying mechanism of disease. Compound Tbx5 and Nos3 haploinsufficiency in mice worsens the cardiac phenotype. The data identify a pathway for endocardial cell survival and unravel a cell-autonomous role for Tbx5 therein. The finding that Nos3, a gene regulated by many congenital heart disease risk factors including stress and diabetes, interacts genetically with Tbx5 provides a molecular framework to understand gene–environment interaction in the setting of human birth defects.

Keywords: heart development, Holt–Oram syndrome

In humans, the incidence of congenital heart disease (CHD) is now estimated to be nearly 5% of live births (1), and CHD is the major noninfectious cause of death in infants within the first year of life. Moreover, undiagnosed less severe defects increase the risks of morbidity and premature mortality and constitute risk factors for stroke, ischemic heart disease, and sudden death (2). Secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) is the third most common congenital heart malformation (3) and occurs as an isolated defect or as a feature of more complex syndromes (4). A complex multifactorial inheritance model involving alterations in multiple genes and interactions with environment factors has been suggested to account for the lower penetrance and variable expressivity of familial ASDs (5). Heart development requires differentiation, proliferation and cell–cell communication between two cell layers composed of myocardial and endocardial cells. Significant progress was accomplished in the past decade in identifying the molecules and mechanisms involved in myocardial cell differentiation (reviewed in refs. 6, 7). Several key regulators of myocardial patterning and chamber specification have been identified. They include transcription factors GATA4, NKX2.5, and TBX5, mutations of which have been associated with human ASDs (4). In contrast, molecular pathways involved in differentiation of the endocardium are only beginning to be elucidated. Valvuloseptal tissues arise from endocardial cells that undergo an epithelial mesenchymal transformation; this process is regulated by myocardial-derived growth factors such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP-2/-4) and VEGF (8, 9). Because genes linked to septal defects (in human or animal models of disease) are either expressed predominantly in myocardial cells or are coexpressed in myocytes and endocardial cells, the cellular basis of septal defects remains undefined.

The molecular pathways underlying endocardial development remain incompletely understood (10–13). A recent report identifies the Ets-related protein-71 as obligatory for endothelial/endocardial specification (14). Consistent with this, FoxC and Ets transcription factors are sufficient to induce ectopic endothelial gene expression and their knockdown in fish disrupted vascular development (15). Others like the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor SCL (16) or Tbx20 (17) and Twist1 (18) are involved in early migration or proliferation of endocardial progenitors. Transcription factors associated with later stages of endocardial cell differentiation include Sox9 (19), Gata5 (20), and NFATc (8, 21, 22). Last, GATA4 is expressed in early endocardial progenitors and persists therein throughout development (20, 23). The exact role of Gata4 in the endocardium is not fully understood but is thought to involve proliferation and remodeling of the endocardial cushion (24). In this study, we show that the transcription factor Tbx5, a member of the Tbox family of important developmental regulators, is expressed in endocardial cells destined to form the atrial septum, where it plays a cell-autonomous role in endocardial cell survival, thus identifying a regulatory pathway in endocardial growth and differentiation. In human, TBX5 mutations are linked to Holt–Oram syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by upper-limb defects and a large spectrum of cardiac malformations ranging from simple arrhythmia to complex structural malformations (25, 26). Conduction defects are thought to be a consequence of Cx40 dysregulation. ASDs are the most common cardiac malformations found in patients with Holt–Oram syndrome (27) and in Tbx5+/− mice (28), but the cellular origin of the defects remains unknown. We now show that endocardial-specific mutation of Tbx5 causes dose-dependent ASDs and that endocardial Tbx5 interacts genetically with Gata4 and endocardial NOS (Nos3) to regulate cell survival and atrial septum formation. The data provide a mechanism to explain synergy between a transcription factor and an enzyme in CHD.

Results

Loss of Tbx5 from the Endocardium Leads to CHD.

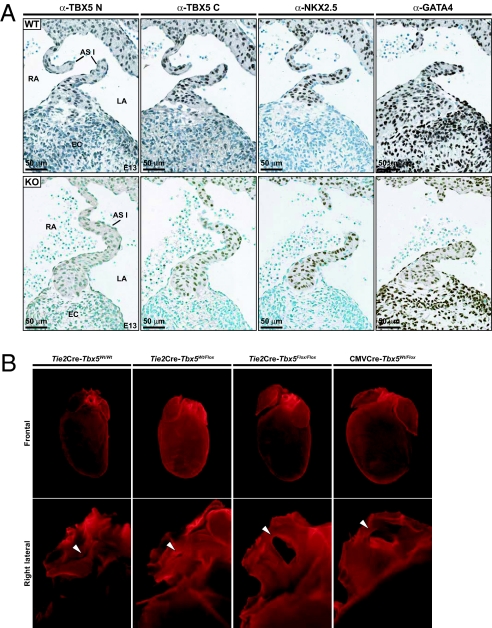

To better identify the cellular distribution of TBX5 within the heart, we performed high-resolution immunohistochemical analysis of TBX5 protein in the developing heart. Labeling with two different TBX5-specific antibodies revealed strong nuclear labeling in atrial and left ventricular myocytes, consistent with previous reports on the distribution of Tbx5 transcripts (27, 28). In addition, labeling was found in cells of the endocardial cushions and in endocardial cells lining the atrial septal walls starting at approximately embryonic day 12.5. In contrast to GATA4, whose expression marked all cells of the endocardial cushion, TBX5 localized in only a subset of EC cells (Fig. S1). To assess the role of Tbx5 in endocardial cells, mice with endocardium-specific deletion of Tbx5 were generated by breeding Tbx5 flox mice (28, 29) with Tie2-cre transgenic mice (30). This breeding removes Tbx5 alleles from all endothelial cells, but because Tbx5 is not expressed in vascular endothelium, the loss of Tbx5 function is restricted to the endocardium. Genotyping of resulting offspring showed that all the expected genotypes were present in a Mendelian ratio, indicating that removal of Tbx5 from endocardial cells is not embryonic-lethal. This contrasts with the embryonic lethality of Tbx5 null mice (28). Immunohistochemistry of tissue sections confirmed loss of TBX5 from EC but not myocardial cells (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Tbx5 expression in endocardial cells. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis of Tbx5 in WT and eTbx5-null mice (KO) at embryonic day 13. Note the absence of Tbx5 from endocardial (negative for α-NKX2.5) but not myocardial cells (positive for αNKX2.5) of eTbx5−/− hearts (LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; AS, atrial septum). (B) Anatomical analysis of eTbx5+/− and eTbx5−/− mice. Different orientation of fixed hearts showing, in frontal view (Top), right atrial dilation and cardiac hypertrophy of the eTbx5−/− and CMV-Cre. Lower Tbx5+/− image is a right lateral view that reveals, after partial excision of the right and left atria, secundum-type ASD (ASD II), indicated by the arrow.

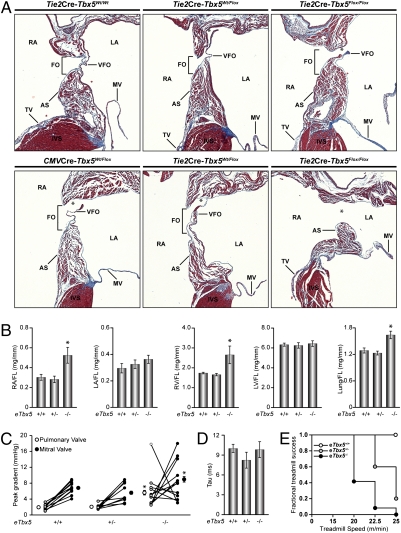

Anatomical examination of adult mice with homozygous deletion of Tbx5 from the endocardium (eTbx5−/−) revealed a cardiac phenotype. At first sight, a right atrial dilation was evident (Fig. 1B, Top) and heart size appeared increased mostly as a result of right ventricular enlargement. A lateral view of the hearts revealed the presence of a secundum type ASD in eTbx5−/− mice and a patent foramen ovale (PFO) in the heterozygote mice (Fig. 1B, Bottom, and Movies S1, S2, and S3). Dissection of more than 20 hearts for each genotype revealed a 65% penetrance of PFOs in eTbx5+/− and 100% penetrance of ASDs (mostly total absence of atrial septum) in eTbx5−/− mice (Fig. 2A). By comparison, the frequency of ASD was 3% (one of 40) in control and Tie2Cre-Tbx5wt/wt mice. Direct measurements of chamber mass confirmed right heart enlargement with increased weight of the right atrium and ventricle in eTbx5−/− mice, whereas no change was found in the left atrium and ventricle (Fig. 2B). Mice lacking Tbx5 in the endocardium were compared with mice lacking one Tbx5 allele in all cell types produced by crossing with CMV-Cre transgenic mice. Tbx5+/−mice (n = 20) showed an intermediary phenotype between eTbx5+/− and eTbx5−/−. Consistent with previously published work (28), they displayed right atrial hypertrophy, ASD, and larger hearts (Fig. 1B, Right). Histologic analysis (Fig. 2A) revealed ASDs and thinning of the valvula foramen ovalis (VFO). These results suggest that myocardial Tbx5 also contributes to proper formation of the atrial septum.

Fig. 2.

Histologic analysis of secundum-type ASDs in eTbx5+/−, eTbx5−/−, and CMV-Cre.Tbx5Wt/Flox mice. (A) Trichrome staining of the atrial septum of control (Tie2Cre.Tbx5Wt/Wt), eTbx5+/−, eTbx5−/−, and CMV-Cre.Tbx5Wt/Flox hearts. Note the severity of the ASD II in eTbx5−/− (Right) compared with the eTbx5+/− hearts (Middle); CMV-Cre.Tbx5Wt/Flox hearts (Lower Left) show an intermediate ASD II between eTbx5+/− and eTbx5−/− hearts. (B) Weighed mass of dissected cardiac chambers and lung, corrected by femur length [RA/LA, right/left atrium; RV, right ventricle; FL, femur length; FO, fossa ovalis; VFO, valvula foraminis ovalis (embryological septum primum or flap valve; TV, tricuspid valve; AS, atrial septum; asterisk depicts secundum type ASDs (ASD II)]. (C) PV and MV pressure gradient. Pulse wave Doppler echography of control (eTbx5+/+), eTbx5+/−, and eTbx5−/− mice revealed an increase in PV pressure gradient in 10 of 13 adult eTbx5−/− mice. Three of 13 eTbx5−/− mice presented an increase in MV pressure gradient but a normal PV pressure gradient that might be caused by the reversal of left-to-right shunting to right-to-left shunting. (D) No change is seen in LV diastolic function. The time constant (τ) of LV isovolumetric pressure was determined by using intracardiac catheterization with a 1.4-F Millar pressure catheter. (E) Fractional treadmill success graph showing the fraction of mice from each genotype that completed each step of the exercise test. Note the dramatically impaired exercise endurance of eTbx5−/− mice. (B and D) Data are presented as mean ± SEM of n = 5–10 per group. (C) Pressure gradient data of each individual mouse are by an open circle (PV) linked to a closed circle (MV); the mean ± SEM is also shown. In B–D, *P < 0.05 vs. eTbx5+/+.

As heterozygote Tbx5 mice have conduction defects (28), electrophysiology of eTbx5−/− mice was assessed using both surface and ambulatory ECG. In young (120 d) mice, there was no significant difference between eTbx5−/− mice and their littermate controls. In aging (450 d) mice, cardiac arrhythmias corresponding to ventricular bigeminism and compensatory pauses were observed in 20% of older eTbx5−/− mice (Fig. S2). This was probably a result of early ventricular depolarization, which could originate in the hypertrophied right ventricle; the sinus rhythm was normal as indicated by equally spaced PP intervals in eTBX5−/− mice (Fig. S2).

Cardiac hemodynamic of eTbx5+/− and eTbx5−/− mice was evaluated by pulse-wave Doppler echography. As expected in the presence of ASD with left-to-right shunting, the pulmonary valve (PV) pressure gradient was increased in eTBX5−/− mice (Fig. 2C). The increased flow to the right atrium caused a volume overload on the right ventricle, which resulted in increased pulmonary flow. Pulmonary volume overload was also evident from increased lung weights in eTbx5+/− and eTbx5–/– mice (Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, 23% (three of 13) of the eTBX5−/− mice presented an increased mitral valve (MV) but normalized PV pressure gradient (Fig. 2C) that could be caused by a reversal of the left-to-right shunting. This has been observed in humans with right ventricle failure or stiffness in which the left-to-right shunting decreases and right-to-left shunting may occur and increase the flow in the left atrium, causing the increase in MV flow (31, 32). Other causes explaining the increased MV pressure gradient were eliminated. Upon close examination of MV, no stenosis was observed except in a few eTbx5−/− mice with the MV appearing thickened. Furthermore, no ductus arteriosus was observed in the eTbx5−/− mice. Left ventricle (LV) diastolic function, which could also affect the MV pressure gradient, was examined by intracardiac catheterization using a 1.4-F Millar pressure catheter, but no alterations were detected. The time constant (τ) of LV isovolumetric pressure decline was not changed in eTbx5+/− and eTbx5−/− mice (Fig. 2D). The impact of the cardiac defect on exercise tolerance using treadmill evaluation revealed an exquisite eTbx5 dose dependence (Fig. 2E). A fractional treadmill success graph shows that none of the eTbx5−/− mice were able to complete the exercise protocol whereas 100% of control littermates succeeded. Mice with one eTbx5 allele had an intermediate profile. Together, these data indicate that endocardial Tbx5 is essential for proper atrial septal formation and point to a primary role for the endocardium in the pathogenesis of ASDs.

Nos3 Is a Genetic Modifier of Tbx5 in Atrial Septal Formation.

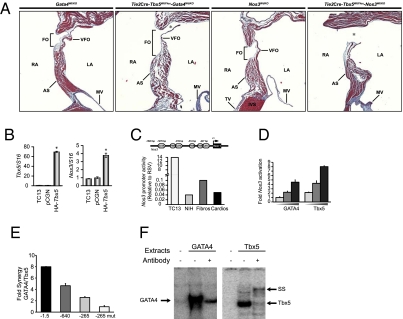

We used eTbx5+/− to identify genetic modifiers of endocardial Tbx5 that contribute to CHD. Two endocardially expressed genes, Gata4 and Nos3 (which encodes endothelial NOS), were tested. GATA4 physically and functionally interacts with TBX5 (33) and a mutation in GATA4 that inhibits in vitro interaction with TBX5 has been linked to human ASD (34). We tested whether disruption of this interaction in the endocardium is linked to ASDs. eTbx5+/− mice were crossed with Gata4+/− mice (35). Compound haploinsufficiency of Gata4 and eTbx5 resulted in reduced viability as double heterozygote mice were born at a lower frequency than expected (16% vs. 25%). Postnatally, 40% of double heterozygotes were lost before weaning; surviving pups displayed severe ASDs that were consistently far more pronounced than in their parents or littermates with only a single deleted allele (Fig. 3A). These results provide genetic evidence that Gata4 and Tbx5 cooperatively regulate cardiac development. Furthermore, they indicate that Gata4/Tbx5 interaction in endocardial cells is essential for proper heart morphogenesis and that mutations in their genes or a decrease in their level or activity may increase the susceptibility for CHD. Next, we tested whether Nos3, a GATA-regulated gene (36), may be a target/effector of TBX5 and GATA4 in endocardial cells. Mice with null deletion of Nos3 display ASDs with very high incidence, but heterozygous littermates have no overt cardiac defects (37). Nos3+//eTbx5+/− mice had reduced viability (by 60%) and the vast majority of the ones who survived to weaning showed type 2 overt ASDs (Fig. 3A, Right), whereas mice lacking a single Nos3 allele presented an intact atrial septum. These results suggest genetic interaction between Nos3 and Tbx5. The possibility that Nos3 may be a downstream TBX5 target was examined. Transient transfection of Tbx5 in the TC13 endocardial progenitor line (20) resulted in 3.5-fold up-regulation of endogenous Nos3 transcripts (Fig. 3B). Bioinformatic analysis of the murine Nos3 locus revealed the presence of three canonical TBX5 binding sites, two of which are flanked by a conserved GATA binding site with the proximal pair being part of an evolutionary conserved composite element that binds both GATA4 and TBX5 with high affinity (Fig. 3F). The ability of TBX5 and GATA4 to activate individually and cooperatively Nos3 transcription was directly tested by using a well studied NOS3-Luc reporter (36). As shown in Fig. 3C, this promoter is highly active in the endocardial TC13 cell line (150 times higher than in cardiomyocytes or fibroblasts). Transfection of Tbx5 or Gata4 enhanced Nos3 promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). Additionally, cotransfection with limiting amounts of both proteins produced cooperative transcriptional enhancement (Fig. 3E); a GATA4 mutant (G295S) that abrogates physical interaction with TBX5 (34) failed to cooperatively activate the Nos3 promoter. Mutation of the composite TBE-GATA element abrogated Tbx5/GATA4 effects (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that Nos3 is a common TBX5/GATA4 target in endocardial cells. They also show that compound haploinsufficiency of eTbx5 and Nos3 exacerbates the cardiac phenotype caused by deletion of a single Tbx5 allele from endocardial cells, suggesting that Nos3 may be a genetic modifier of Tbx5. Given that expression and/or activity of Nos3 is regulated by growth factors including insulin as well as hormonal and mechanical stimuli (38), genetic interaction between Tbx5 and Nos3 may provide a molecular paradigm for understanding gene–environment interactions in CHD.

Fig. 3.

Genetic interaction between Tbx5 and Gata4 and Nos3. (A) Trichrome staining of the atrial septum of eTbx5+/−.Gata4Wt/KO and eTbx5−/−.Nos3Wt/KO mice along with hearts of their Gata4Wt/KO and Nos3Wt/KO littermates. Note the severity of the ASD II in eTbx5+/−.Gata4Wt/KO and eTbx5+/−.Nos3Wt/KO hearts. Abbreviations are as in Fig. 2. (B) Enhanced Nos3 transcripts in TC13 cells transiently overexpressing TBX5 as revealed by quantitative PCR (qPCR). (C) Nos3 promoter activity in various cell types. A schematic representation of the conserved cis-regulatory binding sites upstream of the Nos3 gene is also shown. The results are the mean of four and are expressed relative to RSV-Luc used as external control. (D) Transient transactivation of Nos3 promoter by TBX5 and GATA4 in NIH 3T3 cells. Fifty, 150, and 250 ng of each expression vector were cotransfected with 500 ng of reporter in NIH 3T3. The results are from one representative experiment carried out in duplicate. (E) Fold synergy of GATA4 (50 ng) and Tbx5 (100 ng) on different deletion or point mutants of the Nos3 promoter in NIH 3T3 cells. (F) DNA binding of GATA4 or Tbx5 expressing HEK298 cells on the proximal GATA and TBE elements of the Nos3 promoter.

Loss of eTbx5 Causes Excessive Apoptosis in the Septum Primum.

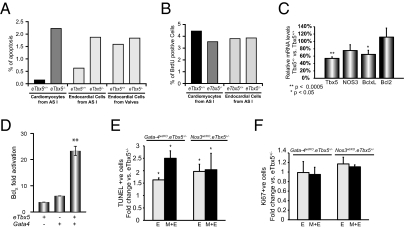

In endothelial/endocardial cells, Nos3 is the main producer of NO, which protects cells from apoptosis by inhibiting caspase activity through S-nitrosylation of an essential cysteine residue (39). Nos3-null fetal hearts display increased apoptosis (37). The finding that Nos3 is a downstream TBX5 target raised the possibility that increased apoptosis may be the mechanism underlying ASDs in eTbx5−/ mice. TUNEL assays indicated excessive apoptosis of the septum primum in eTbx5−/ mice. To facilitate localization of endocardial cells and determine the exact cell types undergoing apoptosis within the septum primum, eTbx5−/− mice were crossed into the Rosa26 transgenic line. Embryo tissue sections were costained with anti-β-Gal (LacZ) antibody to label endocardial cells and antisarcomeric actin to label myocardial cells (Fig. S3). eTbx5−/− showed increased apoptosis of both endocardial and myocardial cells of the septum primum (Fig. 4A). No increase of apoptosis in myocardial or endocardial cells in other regions of the heart was noted. BrdU labeling showed no detectable differences in cell proliferation on consecutive sections (Fig. 4B and Fig. S3). These data suggest that TBX5 is required for endocardial cell survival and endocardial-myocardial cross talk. The effect of TBX5 on cell survival may be mediated by its activation of Nos3, which can also explain how loss of Tbx5 from endocardial cells affects survival of neighboring Tbx5-expressing myocytes through the production of NO. Additionally, we found that TBX5 regulates the antiapoptotic gene BclXL. In Tbx5+/− hearts, BclXL transcripts were significantly decreased by 40% and NOS3 levels were consistently found reduced by 25% (Fig. 4C). Transient overexpression of Tbx5 in the TC13 endocardial progenitor cell line resulted in 60% increase in endogenous BclXL levels. Cotransfection of the BclXL-luciferase reporter with a Tbx5 expression vector resulted in threefold enhancement of BclXL promoter activity. When GATA4 [an upstream activator of BclXL (35)] was added, synergistic activation of BclXL-dependent transcription was produced (Fig. 4D). Thus, BclXL appears to be a target of a TBX5/GATA4 transcription complex and a common effector of their cell survival function.

Fig. 4.

Excessive apoptosis of the septum primum in eTbx5−/− mice. (A) Quantification of apoptotic cells observed in mutant and control mice at embryonic day 14.5. (B) Quantification of BrdU-positive cells in mutant and control mice at embryonic day 14.5 reveal undetectable change of endocardial cell proliferation. (C) Relative mRNA levels of Tbx5, NOS3, BclXL, and Bxl2 in eTbx5 hearts versus their WT littermates (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001). (D) Transient cotransfections of TBX5 and GATA4 expression vectors and with the BclXL-luciferase reporter in NIH 3T3 cells showing synergistic activation of the BclXL promoter. The results are mean ± SEM of six experiments. (E) Fold change in apoptotic cells in the septum primum of Gata-4wt/KO.eTbx5+/− and Nos3wt/KO.eTbx5+/− mice versus their eTbx5+/− littermates in embryonic day 12.5 embryos. “E” stands for endocardial cells only. “M+E” represents the total cells of the septum (myocardial and endocardial). (F) Fold change in the percent of Ki67-positive cells in the septum primum of Gata-4wt/KO.eTbx5+/− and Nos3wt/KO. eTbx5+/− versus their eTbx5+/− littermates in embryonic day 12.5 embryos.

To ascertain whether apoptosis or altered proliferation were the mechanism of ASD in eTbx5/GATA4 and eTbx5/NOS3 double heterogenic mice, immunohistochemistry was carried out on tissue sections from embryonic day 12.5 embryos. As shown in Fig. 4E, TUNEL assays revealed significantly increased apoptosis of both endocardial and myocardial cells of the atrial septum in eTbx5/GATA4 and eTbx5/NOS3 double heterogenic mice compared with either single heterogenic mouse. However, there was no detectable difference in Ki67-positive cells between the different genotypes (Fig. 4F). Together, the results indicate that Nos3 and BclXL are independent effectors of TBX5 in endocardial cell survival and unravel a cell autonomous role for TBX5 in differentiation/survival of septum primum endocardial cells; moreover, they suggest that TBX5 activates therein a system(s) involved in survival of neighboring myocytes that could involve, at least in part, endocardial Nos3-generated NO.

Discussion

Formation of the cardiac septa and valves is essential for proper blood flow and is vital for the human organism and our day-to-day activities. These delicate leaflets develop through a complex multistage process involving highly regulated interactions among different cell types. The results presented here identify a transcription pathway required for differentiation and survival of a subpopulation of endocardial cells involved in interatrial septal formation and suggest early patterning within the endocardial lineage. This insight will facilitate identification of the molecular circuits that underlie the various developmental stages of the endocardial lineage. The work also identifies a cellular pathway to one of the most common forms of CHD. Last, the finding that Nos3, a gene regulated by conditions known to be risk factors for CHD, interacts genetically with Tbx5, provides a framework for understanding gene–environment interactions in the setting of human CHD.

Patterning, Differentiation, and Apoptosis in the Endocardial Lineage.

During recent years, lineage tracing experiments, expression analysis of early myocardial markers, as well as genetic manipulations in several experimental models have established the anteroposterior patterning of the developing myocardium. Although it is clear that the outer myocardial layer of the heart tube is already patterned, little is known about the spatial specification of the inner endocardial layer. Moreover, early markers of the endocardial lineage such as Gata4 and Tbx20 are broadly expressed in all endocardial cells (23, 40). Others, like Gata5 or Sox9, are expressed later in endocardial development but do not show regionalization (19, 20). Reports of regionalized expression in the endocardium are limited. Transcription factor SOX4 was shown to be present only in endocardial ridges and mouse embryos with null Sox4 alleles have impaired semilunar valve development and a common arterial trunk and die at embryonic day 14 of circulatory failure (41). Additionally, a 250-bp NFatc1 enhancer was shown to be expressed in a subpopulation of presumed provalve endocardial cells of the atrioventricular canal and outflow tract (42). Interestingly, mutation of a Hox site therein derepressed expression in other endocardial cells, suggesting that regionalization may result from the interplay of positive and negative regulatory pathways. Of note NFatc1 inactivation in mice leads to embryonic lethality and valve but not septal defects (22). In the present article, we show that Tbx5 is expressed in specific cells of the septum primum and that its deletion therein causes excessive apoptosis and fully penetrant ASDs. Thus, Tbx5 appears to be an exquisite marker of a subset of endocardial cells destined to form the atrial septum. This finding could help further characterize the differentiation pathway and genetic profile of these cells. Aberrant apoptosis accompanies many structural cardiac defects but the molecules and pathways regulating endocardial cell survival are not fully understood (43–45). Here, we show that Tbx5 is a critical survival factor for endocardial cells. Moreover, we provide biochemical and genetic evidence for interaction between Tbx5 and Gata4, whose mutation in human causes septal defects (34). Cooperative TBX5/GATA4 interaction was previously shown to regulate the myocardial Nppa gene (33, 34). The work presented here extends this interaction to the endocardium and identifies two Tbx5 target genes, BclXL and Nos3.

During the finalization of the manuscript, Maitra et al. reported that mice heterozygous for Gata4 and Tbx5 are embryonic or neonatal lethal with severe septal and valve defects (46). These results are consistent with the existence of genetic interaction between Gata4 and Tbx5 in several heart structures but must be interpreted in the context of the phenotype of Tbx5+/− mice who have a broad spectrum of CHD, including ASD, VSD, AVSD, and conduction defects (28). They nevertheless support our results, which further identify the endocardium as a cellular target for TBX5/GATA4 interactions. Interestingly, whereas Maitra et al. (46) found decreased proliferation in Tbx5/Gata4 double heterozygotes, we found only evidence of increased apoptosis, suggesting distinct roles for Tbx5 in endocardial and myocardial cells. This was further supported by gain of Tbx5 function in cultured cells. Finally, the fully penetrant dose-dependent phenotype of eTbx5-null mice is noteworthy. This essential cell autonomous role in atrial septal formation suggests that mutations in Tbx5 may be found in patients with isolated ASDs. Consistent with this, several recent reports have found mutations in Tbx5 in nonsyndromic cases of ASDs (47, 48).

Genetic Predisposition and Environmental Risk Factors in CHD.

The variable expressivity of CHD and the complex pattern of inheritance, together with the identification of environmental risk factors, have led to the conclusion that phenotypic manifestation of most CHDs is likely the result of genetic and environmental factors. This is even the case with an autosomal-dominant syndrome like Holt–Oram syndrome, in which variable expressivity of the same mutation among affected family members remains unexplained (49). Conversely, a number of environmental factors and maternal conditions have been linked to increased risks of CHD. They include, among others, nutrition, cigarette smoking, vitamin deficiencies, hypertension, and diabetes (50). The finding that Nos3 and Tbx5 genetically interact and that Nos3 haploinsufficiency contributes to Tbx5-dependent CHD development is especially noteworthy as it provides a molecular framework for understanding gene–environment interaction in development and disease. Nos3 activity is regulated by numerous conditions and extracellular stimuli including growth factors, histamine, adrenergic agonists, stress, and diabetes, many of which have been linked to increased risks of developmental defects (51). Interestingly, a G894T polymorphism causing decreased enzyme activity and NO production (52) has been associated with increased risks of CHD (53). Our results show that mice with heterozygous mutation in Nos3 have no overt cardiac phenotype. However, compound eTbx5 and Nos3 heterozygous mice have large ASDs, thus providing a molecular understanding for the increased CHD risk in humans with the G894T Nos3 genotype and direct evidence for a role of Nos3 as a Tbx5 modifier in CHD. It also explains the synergistic relationship between a transcription factor and a highly regulated enzyme in cardiac pathogenesis. Finally, the finding that PFO and ASD occur in an eTbx5 dose-dependent manner suggests common genetic determinants and may explain the lower than expected penetrance of familial ASDs. The fact that compound haploinsufficiency of another gene leads to overt ASDs in the offspring of a PFO carrier lends experimental proof to the emerging view that CHD is the result of multiple genetic alterations and points to the importance of careful cardiac evaluation in the stratification of human subjects in genetic studies.

Materials and Methods

Animal Experimentation.

Mice handling and experimentation were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and were approved by the animal care committee. Mice studied were maintained in 129Sv/B6 mixed background. More details of these procedures are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Statistics.

The data are presented as mean ± SEM. For comparison of multiple groups of five to 10, Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric statistical tests were used.

Cell and Molecular Manipulation.

Details on cell and molecular manipulation are included in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Georges Nemer for his advice and contributions to this study, Nathalie Bouchard for technical assistance, Annie Vallée for help with histology, and Lise Laroche and Hélène Touchette for expert secretarial work. G.A. is a clinician scientist of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. M. Nemer was the recipient of a Canada Research Chair. This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grants MOP13057 and GMH79045 (to G.A. and M. Nemer) and by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.0914888107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pierpont ME, et al. American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: Endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007;115:3015–3038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warnes CA. The adult with congenital heart disease: Born to be bad? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruneau BG. The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature. 2008;451:943–948. doi: 10.1038/nature06801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson DW, et al. Reduced penetrance, variable expressivity, and genetic heterogeneity of familial atrial septal defects. Circulation. 1998;97:2043–2048. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.20.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson LE, et al. Homeodomain-mediated beta-catenin-dependent switching events dictate cell-lineage determination. Cell. 2006;125:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemer M. Genetic insights into normal and abnormal heart development. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang CP, et al. A field of myocardial-endocardial NFAT signaling underlies heart valve morphogenesis. Cell. 2004;118:649–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okagawa H, Markwald RR, Sugi Y. Functional BMP receptor in endocardial cells is required in atrioventricular cushion mesenchymal cell formation in chick. Dev Biol. 2007;306:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee RK, Stainier DY, Weinstein BM, Fishman MC. Cardiovascular development in the zebrafish. II. Endocardial progenitors are sequestered within the heart field. Development. 1994;120:3361–3366. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kattman SJ, Huber TL, Keller GM. Multipotent flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Dev Cell. 2006;11:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keegan BR, Meyer D, Yelon D. Organization of cardiac chamber progenitors in the zebrafish blastula. Development. 2004;131:3081–3091. doi: 10.1242/dev.01185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lough J, Sugi Y. Endoderm and heart development. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:327–342. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200004)217:4<327::AID-DVDY1>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferdous A, et al. Nkx2-5 transactivates the Ets-related protein 71 gene and specifies an endothelial/endocardial fate in the developing embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:814–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807583106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Val S, et al. Combinatorial regulation of endothelial gene expression by ets and forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2008;135:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bussmann J, Bakkers J, Schulte-Merker S. Early endocardial morphogenesis requires Scl/Tal1. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shelton EL, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 regulation of endocardial cushion cell proliferation and extracellular matrix gene expression. Dev Biol. 2007;302:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelton EL, Yutzey KE. Twist1 function in endocardial cushion cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation during heart valve development. Dev Biol. 2008;317:282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akiyama H, et al. Essential role of Sox9 in the pathway that controls formation of cardiac valves and septa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6502–6507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemer G, Nemer M. Cooperative interaction between GATA5 and NF-ATc regulates endothelial-endocardial differentiation of cardiogenic cells. Development. 2002;129:4045–4055. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.17.4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer A, et al. Combined loss of Hey1 and HeyL causes congenital heart defects because of impaired epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Circ Res. 2007;100:856–863. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260913.95642.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de la Pompa JL, et al. Role of the NF-ATc transcription factor in morphogenesis of cardiac valves and septum. Nature. 1998;392:182–186. doi: 10.1038/32419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nemer G, Nemer M. Transcriptional activation of BMP-4 and regulation of mammalian organogenesis by GATA-4 and -6. Dev Biol. 2003;254:131–148. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivera-Feliciano J, et al. Development of heart valves requires Gata4 expression in endothelial-derived cells. Development. 2006;133:3607–3618. doi: 10.1242/dev.02519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori AD, Bruneau BG. TBX5 mutations and congenital heart disease: Holt-Oram syndrome revealed. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:211–215. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchhoff S, et al. Reduced cardiac conduction velocity and predisposition to arrhythmias in connexin40-deficient mice. Curr Biol. 1998;8:299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruneau BG, et al. Chamber-specific cardiac expression of Tbx5 and heart defects in Holt-Oram syndrome. Dev Biol. 1999;211:100–108. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruneau BG, et al. A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease. Cell. 2001;106:709–721. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori AD, et al. Tbx5-dependent rheostatic control of cardiac gene expression and morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;297:566–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlaeger TM, et al. Uniform vascular-endothelial-cell-specific gene expression in both embryonic and adult transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3058–3063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256–263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minagoe S, et al. Noninvasive pulsed Doppler echocardiographic detection of the direction of shunt flow in patients with atrial septal defect: Usefulness of the right parasternal approach. Circulation. 1985;71:745–753. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Georges R, Nemer G, Morin M, Lefebvre C, Nemer M. Distinct expression and function of alternatively spliced Tbx5 isoforms in cell growth and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4052–4067. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02100-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg V, et al. GATA4 mutations cause human congenital heart defects and reveal an interaction with TBX5. Nature. 2003;424:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature01827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aries A, Paradis P, Lefebvre C, Schwartz RJ, Nemer M. Essential role of GATA-4 in cell survival and drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6975–6980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401833101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang R, Min W, Sessa WC. Functional analysis of the human endothelial nitric oxide synthase promoter. Sp1 and GATA factors are necessary for basal transcription in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15320–15326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng Q, et al. Development of heart failure and congenital septal defects in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;106:873–879. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000024114.82981.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Massion PB, Balligand JL. Modulation of cardiac contraction, relaxation and rate by the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS): Lessons from genetically modified mice. J Physiol. 2003;546:63–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dimmeler S, Haendeler J, Nehls M, Zeiher AM. Suppression of apoptosis by nitric oxide via inhibition of interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme (ICE)-like and cysteine protease protein (CPP)-32-like proteases. J Exp Med. 1997;185:601–607. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeuchi JK, et al. Tbx20 dose-dependently regulates transcription factor networks required for mouse heart and motoneuron development. Development. 2005;132:2463–2474. doi: 10.1242/dev.01827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schilham MW, et al. Defects in cardiac outflow tract formation and pro-B-lymphocyte expansion in mice lacking Sox-4. Nature. 1996;380:711–714. doi: 10.1038/380711a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou B, et al. Characterization of Nfatc1 regulation identifies an enhancer required for gene expression that is specific to pro-valve endocardial cells in the developing heart. Development. 2005;132:1137–1146. doi: 10.1242/dev.01640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdelwahid E, Rice D, Pelliniemi LJ, Jokinen E. Overlapping and differential localization of Bmp-2, Bmp-4, Msx-2 and apoptosis in the endocardial cushion and adjacent tissues of the developing mouse heart. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;305:67–78. doi: 10.1007/s004410100399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keyes WM, Sanders EJ. Regulation of apoptosis in the endocardial cushions of the developing chick heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1348–C1360. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00509.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zwerts F, et al. Lack of endothelial cell survivin causes embryonic defects in angiogenesis, cardiogenesis, and neural tube closure. Blood. 2007;109:4742–4752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maitra M, et al. Interaction of Gata4 and Gata6 with Tbx5 is critical for normal cardiac development. Dev Biol. 2009;326:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reamon-Buettner SM, Borlak J. TBX5 mutations in non-Holt-Oram syndrome (HOS) malformed hearts. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:104. doi: 10.1002/humu.9255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faria MH, Rabenhorst SH, Pereira AC, Krieger JE. A novel TBX5 missense mutation (V263M) in a family with atrial septal defects and postaxial hexodactyly. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brassington AM, et al. Expressivity of Holt-Oram syndrome is not predicted by TBX5 genotype. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:74–85. doi: 10.1086/376436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins KJ, et al. American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: Endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007;115:2995–3014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tyagi SC, Hayden MR. Role of nitric oxide in matrix remodeling in diabetes and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2003;8:23–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1022138803293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cherney DZ, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms and the renal hemodynamic response to L-arginine. Kidney Int. 2009;75:327–332. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Beynum IM, et al. Common 894G>T single nucleotide polymorphism in the gene coding for endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and risk of congenital heart defects. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:1369–1375. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel VV, et al. Electrophysiologic characterization and postnatal development of ventricular pre-excitation in a mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:942–951. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00850-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iglarz M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and receptor-gamma activators prevent cardiac fibrosis in mineralocorticoid-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:737–743. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000083511.91817.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.