Abstract

Background

Rod-cone dystrophies are heterogeneous group of inherited retinal disorders both clinically and genetically characterized by photoreceptor degeneration. The mode of inheritance can be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-linked. The purpose of this study was to identify mutations in one of the genes, PRPF31, in French patients with autosomal dominant RP, to perform genotype-phenotype correlations of those patients, to determine the prevalence of PRPF31 mutations in this cohort and to review previously identified PRPF31 mutations from other cohorts.

Methods

Detailed phenotypic characterization was performed including precise family history, best corrected visual acuity using the ETDRS chart, slit lamp examination, kinetic and static perimetry, full field and multifocal ERG, fundus autofluorescence imaging and optic coherence tomography. For genetic diagnosis, genomic DNA of ninety families was isolated by standard methods. The coding exons and flanking intronic regions of PRPF31 were PCR amplified, purified and sequenced in the index patient.

Results

We showed for the first time that 6.7% cases of a French adRP cohort have a PRPF31 mutation. We identified in total six mutations, which were all novel and not detected in ethnically matched controls. The mutation spectrum from our cohort comprises frameshift and splice site mutations. Co-segregation analysis in available family members revealed that each index patient and all affected family members showed a heterozygous mutation. In five families incomplete penetrance was observed. Most patients showed classical signs of RP with relatively preserved central vision and visual field.

Conclusion

Our studies extended the mutation spectrum of PRPF31 and as previously reported in other populations, it is a major cause of adRP in France.

Background

Rod-cone dystrophies, also called retinitis pigmentosa (RP), are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of inherited retinal disorders usually primarily affecting rods with secondary cone degeneration [1-4]. It represents a progressive disorder which often starts with night blindness and leads to visual field constriction, abnormal color vision and can eventually lead to loss of central vision and complete blindness. It is the most common inherited form of severe retinal degeneration, with a frequency of about 1 in 4000 births and more than 1 million individuals affected worldwide. The mode of inheritance can be X-linked (5-15%), autosomal dominant (30-40%) or autosomal recessive (50-60%). The remaining patients represent isolated cases for which the inheritance trait cannot be established [5].

To date, mutations in 20 different genes are associated with autosomal dominant RP (adRP) http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet/. The majority of prevalence studies reveal rhodopsin (RHO) being the most frequently mutated gene in adRP [6]. PRPF31 was also proposed to represent a major gene underlying this disorder. It is located on chromosome 19q13.42, encompasses 14 exons and codes for a ubiquitously expressed pre-mRNA splicing factor [7]. According to published reports, PRPF31 mutation prevalence ranges from 1 to 8% in adRP cohorts from various geographical origins, with higher frequencies reported in the United States [8-15].

To date over 40 mutations have been located in different parts of the gene. The mutation spectrum comprises missense, splicing, regulatory and nonsense mutations. In addition small or gross insertions, small insertion-deletions, and small or gross deletions were identified (http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet/, http://www.retina-international.org/sci-news/prp31mut.htm) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previously described PRPF31 mutations in adRP patients.

| Exon/Intron | Nucleotide Exchange | Protein Effect | Publication | Information about penetrance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int1 | c.1-2481G>T (formerly: IVS1+1G>T) | splice defect | [27] | incomplete |

| 2 | c.79G>T | p.Glu27X | [15] | Incomplete |

| Int2 | c.177+1G>A | splice defect | [13] [23] |

Simplex Simplex |

| 3 | c.220C>T | p.Gln74X2 | [13] | Simplex |

| 4 | c.319C>G | p.Leu107Val (interferes with splice site leading to frameshift) | [23] | Simplex |

| Int4 | c.323-2A>G | Splice defect | [23] | Simplex |

| 5 | c.331_342del | p.His111_Ile114del | [22] | High |

| 5 | c.358_359delAA | p.Lys120GlufsX122 | [9] | Simplex |

| 5 | c.390delC | p.Asn131MetfsX67 (formerly p.Asn131fs7ter197) | [13] | segregates in 3 affected |

| 5 | c.413C>A (formerly c.412C>A) | p.Thr138Lys | [15] | Incomplete |

| Int5 | c.421-1G>A | splice defect | [28] | Incomplete |

| 6 | c.421G>T | p.Glu141X | [13] | Simplex |

| Int6 | c.527+1G>T | splice defect | [29] | Incomplete |

| Int6 | c.527+1G>A | splice defect | [9] | Incomplete |

| Int6 | c.527+3A>G | splice defect | [7,16] [15] |

Incomplete incomplete |

| Int6 | c.528-1G>A | splice defect | [15] | not tested |

| Int6 | c.528-3_45del (previous description: IVS6-3 to -45 del) | splice defect | [7,12] | Incomplete |

| 7 | c.581C>A | p.Ala194Glu | [7] | Simplex |

| 7 | Formerly: 580-581dup33bp | formerly: in frame insertion of 11 amino acids | [7] | Simplex |

| 7 | c.636delG | p.Met212IlefsX27 (formerly: Met212fs/ter238) | [13] | segregates in 2 affected |

| 7 | c.646G>C | p.Ala216Pro | [7] | Incomplete |

| 8 | c.732_737delins20bp | p.Met244fsX248 | [11] | segregated in 2 affected |

| 8 | c.758_767del | p.Gly253AlafsX65 (formerly: p.Gly253fs/ter317) | [13] | Simplex |

| 8 | c.769_770insA | p.Thr258AspfsX21 (formerly: frameshift, 20 novel amino acids then STOP) (formerly:Lys257fsX277) | [7] [11] |

Simplex incomplete |

| 8 | c.785delT | p.Phe262SerfsX59 | [10] | |

| 8 | c.828_829delCA | p.His276GlnfsX2 (formerly p.His276fsX237) | [11] | Incomplete |

| Int8 | c.856-2A>G | splice defect | [23] | segregated in 2 affected |

| 9 | c.871G>C | p.Ala291Pro | [13] | Simplex |

| 9 | c.877_910del | p.Arg293_Arg304>ValfsX17 | [23] | Incomplete |

| 9 | c.895T>C | p.Cys299Arg | [13] | Incomplete |

| 10 | c.973G>T | p.Glu325X | [13] | Simplex |

| 10/int10 | 1049_IVS10+20del/insCCCCT | splice defect | [13] | Simplex |

| Int10 | c.1073+1G>A (Formerly:IVS10+1G>A) | splice defect | [13] | segregates in 5 affected |

| 11 | c.1115_1125del | p.Arg372GlnfsX99 (formerly: frameshift, 98 novel amino acids then STOP) | [7] | Incomplete |

| 11 | c.1142delG | p.Gly381GlufsX32 | [12] | Incomplete |

| Int11 | c.1146+2T>C | Splice defect | [15] | Incomplete |

| 12 | c.1155_1159delGGACG/insAGGGATT | p.Asp386GlyfsX28 | [12] | Incomplete |

| Int13 | c.1374+654C>G | Splice defect | [19] | Incomplete |

| ex1/int1 | indel ex1/int1 | Loss of one copy of PRPF31 | [14] | Incomplete |

| 4-8 | 4.8 kb deletion | Loss of one copy of PRPF31 | [14] | simplex |

| 4-13 | 11.3 kb deletion | Loss of one copy of PRPF31 | [14] | incomplete |

| PRPF31: 1-11, TFPT, NDUFA3, partly OSCAR | 59 kb deletion | Loss of one copy of PRPF31 | [30] | incomplete |

| PRPF31, TFPT, NDUFA3, partly OSCAR | 32-42 kb deletion | Loss of one copy of PRPF31 | [14] | simplex |

| PRPF31, TFPT, NDUFA3, OSCAR | > 44.8 kb deletion | Loss of one copy of PRPF31 | [14] | simplex |

| PRPF31 without Stop codon, TFPT NDUFA3, promoter OSCAR | 30 kb deletion | Loss of one copy of PRPF31 | [31] | incomplete |

If possible, mutations are indicated according to NM_015629 by using the recommendations of human genome variation society: http://www.hgvs.org/rec.html and/or the nomenclature of the original publication are given

The phenotype, age of onset and the severity of the disease in adRP patients varied with different PRPF31 mutations. In addition, in some families the same mutation was even associated with a range of phenotypic variations [15]. Furthermore, several studies revealed that incomplete penetrance is a common feature in families showing PRPF31 mutations with an asymptomatic mutation carrier having a carrier child, who fully manifests the disease [16-18].

Our comprehensive study reported here aims to perform for the first time genotype-phenotype correlations in a French adRP cohort with PRPF31 mutations. All patients were recruited from the same clinical center, namely the Quinze-Vingts hospital in Paris. We will present the prevalence of PRPF31 mutations in this cohort and compare our findings with other studies.

Methods

Clinical assessment

Ninety families with a provisional diagnosis of autosomal dominant rod-cone dystrophy, (adRP) were ascertained in the Clinical Investigating Centre of Quinze-Vingts Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and normal controls after explanation of the study and its potential outcome. The study protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee. Each patient underwent full ophthalmic examination with clinical assessment as described earlier [6]. For additional family members who could not come to our centre for examination, ophthalmic records were obtained from local ophthalmologists.

Mutation detection

Total genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes according to manufacturer recommendation (Puregen Kit, Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). Subsequently, direct genomic sequencing of PRPF31 was performed. All 14 exons of which exons 2-14 are coding, and flanking intronic regions of PRPF31 were PCR amplified in 10 fragments (PRPF31 RefSeq NM_015629) using oligonucleotides previously described [7] and a polymerase (HotFire, Solis Biodyne, Estonia) in the presence of 2.5 mM MgCl2 and at an annealing temperature of 60°C. The PCR products were enzymatically purified (ExoSAP-IT, USB Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio, USA purchased from GE Healthcare, Orsay, France) and sequenced with a commercially available sequencing mix (BigDyeTerm v1.1 CycleSeq kit, Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). The sequenced products were purified on a presoaked Sephadex G-50 (GE Healthcare) 96-well multiscreen filter plate (Millipore, Molsheim, France), the purified product analyzed on an automated 48-capillary sequencer (ABI 3730 Genetic analyzer, Applied Biosystems) and the results interpreted by applying a software (SeqScape, Applied Biosystems). At least 192 commercially available control samples were used to validate the pathogenicity of the novel sequence variants (Human random control panel 1-3, Health Protection Agency Culture Collections, Salisbury, United Kingdom).

Multiplex Ligation dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) was performed using a commercially available kit (SALSA MLPA kit P235-B1 Retinitis, MRC Holland). The MLPA reactions were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions and analyzed on an automated 48-capillary sequencer (ABI 3730 Genetic analyzer, Applied Biosystems). MLPA data analysis was performed using GeneMarker (Softgenetics) and additionally Coffalyser (MRC Holland) software. Five control DNAs were included in each MLPA run and the data was interpreted in terms of the ratio of each probe signal between the control and patient DNA samples. Samples with probe ratio values below 0.6 were considered as deletions and values above 1.4 as duplications.

Results and Discussion

Samples included in this study are part of a French cohort of adRP patients that were previously screened for RHO mutations and we noted 16.5% of cases with known or novel RHO mutations [6].

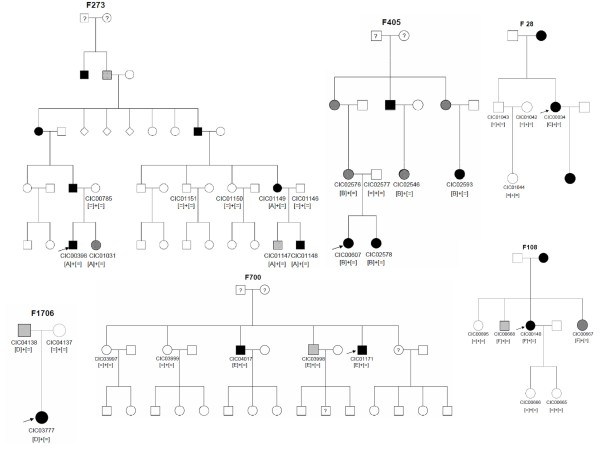

In the current study we report the identification of novel PRPF31 mutations in six of the 90 adRP index patients. In total two deletions, three duplications and a splice site mutation all over the gene were identified (Table 2). The respective deletions and duplications were predicted to lead to premature stop codons. The novel splice site mutation c.527 + 2T>C resides in the highly conserved donor site of exon 6, which is predicted to lead to skipping of exon 6. Co-segregation analysis revealed in all but one family incomplete penetrance (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Novel PRPF31 mutations in a French adRP cohort.

| Index (families) | Exon | Nucleotide Exchange | Protein Effect | Information about Penetrance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIC00398 (F273) | 4 | c.269_273del | p.Tyr90CysfsX21 | incomplete |

| CIC00607 (F405) | Int6 | c.527+2T>C | splice defect | incomplete |

| CIC00034 (F28) | 7 | c.666dup | p.Ile223TyrX56 | segregates (1 affected show mutation, 3 unaffected no mutation) |

| CIC03777 (F1706) | 8 | c.709_734dup | p.Cys247X | incomplete |

| CIC01171 (F700) | 9 | c. 873_897dup | p.Thr300GlyfsX32 | incomplete |

| CIC00140 (F108) | 10 | c.997delG | p.Glu333SerfsX5 | incomplete |

Mutations are indicated according to NM_015629.3 by using the recommendations of human genome variation society: http://www.hgvs.org/rec.html.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of adRP patients with PRPF31 mutations and co-segregation in available family members. Filled symbols represent affected, unfilled unaffected and dotted asymptomatic individuals. Question marks indicate that it is not clear whether the individual is affected or not. Squares depict males, circles females. Arrows mark the index patients. Equation symbols represent unaffected alleles. The identified mutations were abbreviated as followed: A = c.269_273del, B = c.527+2T>C, C = c.666dup, D = c.709_734dup, E = c.873_897dup and F = c.997delG.

To detect large deletions in those patients (60 patients) where no mutations was detected by direct sequencing approaches, MLPA studies were performed. However, no additional deletion was found by this method.

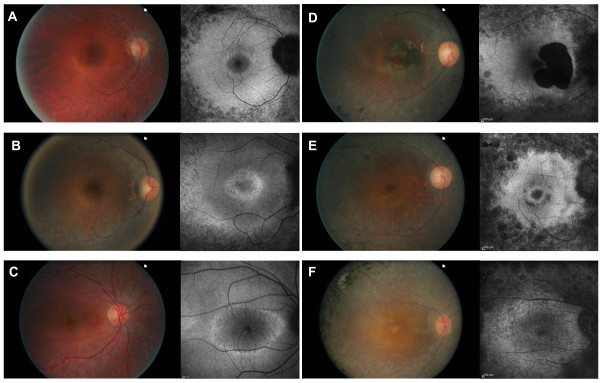

Phenotypic characteristics of the 6 index patients are summarized in table 3 and 4. Four of them were females and two males with age ranging from 23 to 44 years with an average age of 34.5 years. Age at time of diagnosis ranged from 5 to 43 with an average of 19.5 years. Symptoms that led to the diagnosis were dominated by night blindness in all patients but one (CIC01171). Two patients also complained of visual field constrictions (CIC00034 and CIC01171). Refractive errors were variable. Central visual acuity was relatively preserved except in one patient (CIC00140), age 31, who had decreased central vision that just qualified her for legal blindness. Preserved central vision was well correlated with preserved responses to central hexagons in multifocal ERG. All patients showed visual field constriction with some peripheral perception, except for one patient (CIC00607), age 23, who had a relatively normal binocular visual field. This patient was the only one with detectable responses for both scotopic and photopic condition on ERG. Color vision was normal in 3 patients or showed tritan defect in one eye for one patient (CIC00607) and both eyes for patients CIC00140 and CIC03777 who also had low visual acuity. Anterior segment examination showed moderate posterior subcapsular cataract only in one patient (CIC00034), age 42. Fundus examination showed typical peripheral signs of RP with variable posterior pole involvements (Figure 2) including one patient with cystoid macular edema (CIC00607, Figure 2B), one patient with an area of parafoveal well-demarcated atrophy (CIC00034, Figure 2C), two patients with perifoveal atrophic changes (CIC01171, Figure 2D, CIC03777, Figure 2F) and one patient with foveal thinning (CIC00140, Figure 2E). This would suggest that central involvement is not uncommon in the course of the disorders and that central changes can occur as early as age 31 (patient CIC00140, Figure 2E). These cone dysfunction and macular changes can lead to further decrease in central vision and central cone survival should be the major target of future therapeutic intervention.

Table 3.

Clinical data of affected members from families with adRP due to PRPF31 mutations

| Family and PRPF31 mutation | Patient | Age at time of testing | Age at time of diagnosis | Sex | Family history | Symptoms at time of diagnosis | BCVA OD/OS Refraction | Lens | Fundus examination | OCT | FAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F273 | CIC398 | 23 | 5 | M | From North of Brittany Father affected and few |

Night blindness | 20/25 20/20 -6.25(-1.75)20° -5.50(-1.25)175° |

clear | Normal disc color, narrowed retinal vessels, little RPE changes in the periphery, | Preserved foveal lamination | Loss of AF outside the vascular arcades, perifoveal ring of increased AF |

| F405 | CIC00607 | 23 | 20 | F | One sister affected, cousins on maternal side affected Mother not affected incomplete penetrance From French descent |

Night blindness late teens | 20/32 20/32 +0.75(-2.75)15° Plano(-1.75)175° |

clear | Bilateral ERM Normal disc color; no narrowing of blood vessels; little changes in the periphery with few bone spicules | Bilateral ERM Bilateral CME | Perifoveal ring of increased AF; foveal changes due to CME |

| F28 | CIC00034 | 42 | 18 | F | Family from Cameroun, daughter mother and one brother affected, no notion of incomplete penetrance | Night blindness and visual field constriction | 20/32 20/32 -3.25(-0.75)65° -3.25(-0.75)130° |

Small posterior subcapsular opacities | Disc pallor narrowed, blood vessels, RPE changes in periphery, bilateral atrophic lesion off the fovea | Preserved foveal lamination | Loss of AF outside the vascular arcades, round eccentric parafoveal area of loss of AF, no ring of AF |

| F1706 | CIC03777 | 44 | 8 | F | Paternal grand-mother, great-grand mother and one great-uncle on father side affected, French family from Jewish Ashkenazi ancestry | Night blindness since age 7 | 20/125 20/160 +0.5(-1.25)40° +0.25(-1.50)155° |

pseudophakic | Pale optic disc, narrowed retinal vessels | Preserved foveal lamination | Loss of AF outside the vascular arcades, patchy loss of AF within the posterior pole with no ring of AF |

| F700 | CIC01171 | 44 | 43 | M | One elder brother affected, one niece affected from one of his unaffected sister, one uncle on father side Incomplete penetrance family originating from the Mauritius Island |

Visual field constriction, no real night blindness | 20/32 20/25 -0.50(-3.75)15° -0.25(-3.75)175° |

clear | Normal disc color, narrowed retinal vessels, RPE changes in the periphery | Preserved foveal lamination | Loss of AF outside the vascular arcades; small perifoveal ring of increased autofluorescence with some perifoveal areas of loss of AF |

| F108 | CIC00140 | 31 | 23 | F | Mother, maternal grand-mother affected; family from Ivory Coast | Night blindness since birth | 20/500 20/200 +1.50(-1.25)95° +1.50(-1.25)75° |

clear | No pale optic disc; narrowed retinal vessels, some RPE changes in the periphery | Foveal thinning | Loss of AF outside the vascular arcades, increased AF within the foveal region associated with some patchy loss of AF |

BCVA Best Corrected Visual Acuity; CME: Cystoid Macular Edema; ERM: Epi Retinal Membrane; AF: autofluorescence; OCT: optic coherence tomography OD: Oculis dextra (right eye); OS: Oculis Sinistra (center eye); RPE: Retinal Pigment Epithelium.

Table 4.

Functional data.

| Patient | Color vision | Binocular Goldman visual field, III4 isopter | Full field ERG | Multifocal ERG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIC00398 | ODS normal at 28 saturated Farnworth Hue | 20° both horizontally and vertically with a large island of perception in temporal and inferior periphery | Only residual cone responses | Relatively well preserved central responses |

| CIC00607 | OD tritan defect; OS normal at Farnsworth 15Desaturated Hue | 180° horizontally ×110° vertically | Rod-cone dysfunction with 80% of normal for scotopic 3.0cd.s/m2 ERG amplitude and 50% of normal for photopic 3.0cd.s.m2 | Relatively well preserved central responses |

| CIC00034 | ODS normal at 28 saturated Farnworth Hue | 20° both horizontally and vertically with 2 bitemporal island of perception in periphery | ND | Only preservation of responses to central hexagons |

| CIC03777 | ODS tritan defext at 28 saturated Farnworth Hue | 20° both horizontally and vertically | ND | Only residual responses to central hexagons |

| CIC01171 | ODS normal at 28 saturated Farnworth Hue | 20° both horizontally and vertically | ND | Only preservation of responses to central hexagons |

| CIC00140 | ODS tritan defext at 28 saturated Farnworth Hue | 30° both horizontally and vertically with a large island of perception in temporal and inferior periphery | ND | Only residual responses to central hexagons |

NP: not performed; ND: not detectable, OD: Oculus Dexter; OS: Oculus Sinister

Figure 2.

Color fundus photograph and autofluorescence imaging of the right eye for each index patient: A: CIC0398; B: CIC00607; C: CIC00034; D: CIC01171; E CIC00140; F: CIC03777.

Due to the small number of index patients included in this study, it is difficult to draw general conclusions on phenotypic variability and phenotype/genotype correlation. However, our cohort still shows on one hand one patient with reduced but still detectable rod-cone responses and well preserved central vision (CIC00607) at age 23 and on the other hand one legally blind patient with undetectable ERG (CIC00140), at age 31, suggesting variable severity of the disorder. This variable severity of the disorder is in accordance with previous reports, which also mentioned the possible role of unknown modifier genes [15]. Further longitudinal studies are required to document retinal degeneration kinetics and especially macular involvement in order to prepare the patients for future treatment.

With the study presented here we report 6 novel mutations in a French cohort leading to variable severity of adRP. To our knowledge, this is the first report on PRPF31 mutation screening and prevalence in the French population and it further expands the mutation spectrum causing adRP. In total two deletions, three duplications and a splice site mutation were identified (Table 2). To date only few PRPF31 variations have been reported to be recurrent (Table 1). This holds also true for our study. Consistent with previous reports, we propose that these mutations also lead to loss of function of PRFP31 and thus to haploinsufficiency [19-21]. In five of our families incomplete penetrance was observed. Only in one family (family 28) no asymptomatic mutation/or obligate carriers were reported. This was confirmed on three unaffected family members who did not reveal a mutation. However, due to the small size of the family, incomplete penetrance cannot be formally excluded for this mutation. To our knowledge, to date only one large Chinese family was reported with high penetrance [22], suggesting that most of the PRPF31 mutations are indeed associated with incomplete penetrance. Although the presumed mechanism to explain this phenomenon is allelic imbalance with over-expression of the wild-type allele, compensating for the non-functional allele in asymptomatic carriers [21,23], the exact mechanism how this over-expression happens remains to be solved.

Patient data and mouse in vivo studies strongly suggest that the disease mechanism is caused by haploinsufficiency rather than dominant negative effect. A recent study in mice demonstrated that p.A216P mutation as well as deletion of Prpf31 exon 7 in mice lead to null alleles [24]. Mice heterozygous for these mutations did not reveal signs of retinal degeneration in histological, ERG and fundus examination, however in homozygous state they were embryonic lethal, demonstrating lack of function of the mutant Prpf31 alleles. In a number of studies a cytotoxic effect of PRPF31 mutations has been suggested [25,26]. We believe that this toxicity plays a minor role in the development of the disease since asymptomatic mutation carriers do not develop retinal degeneration.

The study presented here reveals a prevalence of 6.7% in adRP cases due to PRPF31 mutations. This is higher than in another study from UK with 5% [15], in a study from India (4%), from Japan with 3% [12], from Spain with 1.7% [11] and from China with 1% [10]. A prevalence study by Sullivan and co-workers (2006) in 200 US families of presumably UK origin revealed 5.5% of cases with PRPF31 mutations. However, these numbers were corrected to 8% when MLPA studies revealed larger deletions, which were not detectable by direct sequencing approaches [14]. In contrast to these findings, our MLPA studies did not reveal any large deletions or duplications in this cohort. Therefore, we conclude that genomic rearrangements in the PRPF31 gene are not common in the French adRP cohort.

Conclusions

With the study presented here we report six novel mutations in a French cohort leading to variable severity of adRP in families with mainly incomplete penetrance. In 6.7% of this cohort PRPF31 mutations were detected, rendering this gene a major gene for adRP in France. Consistent with previous reports, we propose that mutations in PRPF31 are mainly not recurrent, lead to loss of function of PRFP31 and thus to haploinsufficiency.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

IA contributed to the design of the study, the acquisition and interpretation of clinical data, and drafted the manuscript. KB contributed to the design and interpretation of the MLPA studies. S MS contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of clinical data. M-E L, V M-D, NH W and A A performed the DNA extraction and sequence analysis. J-A S contributed to the design of the study. SSB contributed to the design of the study, and helped to draft the manuscript. CZ contributed to the design of the study, the acquisition and interpretation of molecular genetic data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Isabelle Audo, Email: isabelle.audo@inserm.fr.

Kinga Bujakowska, Email: kinga.bujakowska@inserm.fr.

Saddek Mohand-Saïd, Email: mohand@quinze-vingts.fr.

Marie-Elise Lancelot, Email: marie-Elise.Lancelot@inserm.fr.

Veselina Moskova-Doumanova, Email: veselina.doumanova@inserm.fr.

Naushin H Waseem, Email: n.waseem@ucl.ac.uk.

Aline Antonio, Email: aline.antonio@inserm.fr.

José-Alain Sahel, Email: j.sahel@gmail.com.

Shomi S Bhattacharya, Email: smbcssb@ucl.ac.uk.

Christina Zeitz, Email: christina.zeitz@inserm.fr.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to patients and family members described in this study, to Thierry Léveillard, Dominique Santiard-Baron, Christine Chaumeil and clinical staff for their help in clinical data and DNA collection. The project was financially supported by the Department of Paris, Foundation Fighting Blindness (I.A. FFB Grant N°: CD-CL-0808-0466-CHNO and the CIC503 recognized as an FFB center, FFB Grant No: C-CMM-0907-0428-INSERM04), ANR NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology and The Special Trustees of Moorfields Eye Hospital London, Foundation Voir et Entendre (C.Z), EU FP6, Integrated Project 'EVI-GENORET' (LSHG-CT-2005-512036) and Ville de Paris et Région Ile de France.

References

- Birch DG, Fish GE. Rod ERGs in retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:140–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM, Sidman RL. Differential effect of the rd mutation on rods and cones in the mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978;17:489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Hood DC, Huang Y, Banin E, Li ZY, Stone EM, Milam AH, Jacobson SG. Disease sequence from mutant rhodopsin allele to rod and cone photoreceptor degeneration in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7103–7108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam AH, Li ZY, Fariss RN. Histopathology of the human retina in retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17:175–205. doi: 10.1016/S1350-9462(97)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audo I, Manes G, Mohand-Said S, Friedrich A, Lancelot ME, Antonio A, Moskova-Doumanova V, Poch O, Zanlonghi X, Hamel CP. et al. Spectrum of rhodopsin mutations in French autosomal dominant rod-cone dystrophy patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3687–3700. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vithana EN, Abu-Safieh L, Allen MJ, Carey A, Papaioannou M, Chakarova C, Al-Maghtheh M, Ebenezer ND, Willis C, Moore AT. et al. A human homolog of yeast pre-mRNA splicing gene, PRP31, underlies autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa on chromosome 19q13.4 (RP11) Mol Cell. 2001;8:375–381. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiger SP, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS. Perspective on genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:151–158. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandra M, Anandula V, Authiappan V, Sundaramurthy S, Raman R, Bhattacharya S, Govindasamy K. Retinitis pigmentosa: mutation analysis of RHO, PRPF31, RP1, and IMPDH1 genes in patients from India. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1105–1113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KP, Yip SP, Cheung SC, Leung KW, Lam ST, To CH. Novel PRPF31 and PRPH2 mutations and co-occurrence of PRPF31 and RHO mutations in Chinese patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:784–790. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gimeno M, Gamundi MJ, Hernan I, Maseras M, Milla E, Ayuso C, Garcia-Sandoval B, Beneyto M, Vilela C, Baiget M. et al. Mutations in the pre-mRNA splicing-factor genes PRPF3, PRPF8, and PRPF31 in Spanish families with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2171–2177. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Wada Y, Itabashi T, Nakamura M, Kawamura M, Tamai M. Mutations in the pre-mRNA splicing gene, PRPF31, in Japanese families with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:537–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Birch DG, Hughbanks-Wheaton D, Heckenlively JR, Lewis RA, Garcia CA, Ruiz RS, Blanton SH, Northrup H. et al. Prevalence of disease-causing mutations in families with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa: a screen of known genes in 200 families. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3052–3064. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Seaman CR, Blanton SH, Lewis RA, Heckenlively JR, Birch DG, Hughbanks-Wheaton D, Daiger SP. Genomic rearrangements of the PRPF31 gene account for 2.5% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4579–4588. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waseem NH, Vaclavik V, Webster A, Jenkins SA, Bird AC, Bhattacharya SS. Mutations in the gene coding for the pre-mRNA splicing factor, PRPF31, in patients with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1330–1334. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maghtheh M, Vithana E, Tarttelin E, Jay M, Evans K, Moore T, Bhattacharya S, Inglehearn CF. Evidence for a major retinitis pigmentosa locus on 19q13.4 (RP11) and association with a unique bimodal expressivity phenotype. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:864–871. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K, al-Maghtheh M, Fitzke FW, Moore AT, Jay M, Inglehearn CF, Arden GB, Bird AC. Bimodal expressivity in dominant retinitis pigmentosa genetically linked to chromosome 19q. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:841–846. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.9.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee TL, Devoto M, Ott J, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Evidence that the penetrance of mutations at the RP11 locus causing dominant retinitis pigmentosa is influenced by a gene linked to the homologous RP11 allele. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1059–1066. doi: 10.1086/301614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio Frio T, McGee TL, Wade NM, Iseli C, Beckmann JS, Berson EL, Rivolta C. A single-base substitution within an intronic repetitive element causes dominant retinitis pigmentosa with reduced penetrance. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1340–1347. doi: 10.1002/humu.21071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio Frio T, Wade NM, Ransijn A, Berson EL, Beckmann JS, Rivolta C. Premature termination codons in PRPF31 cause retinitis pigmentosa via haploinsufficiency due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1519–1531. doi: 10.1172/JCI34211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vithana EN, Abu-Safieh L, Pelosini L, Winchester E, Hornan D, Bird AC, Hunt DM, Bustin SA, Bhattacharya SS. Expression of PRPF31 mRNA in patients with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa: a molecular clue for incomplete penetrance? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4204–4209. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ribaudo M, Zhao K, Yu N, Chen Q, Sun Q, Wang L, Wang Q. Novel deletion in the pre-mRNA splicing gene PRPF31 causes autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa in a large Chinese family. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;121A:235–239. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivolta C, McGee TL, Rio Frio T, Jensen RV, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Variation in retinitis pigmentosa-11 (PRPF31 or RP11) gene expression between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with dominant RP11 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:644–653. doi: 10.1002/humu.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujakowska KM, Maubaret C, Chakarova CF, Tanimoto N, Beck SC, Fahl E, Humphries MM, Kenna P, Makarov E, Makarova O, Paquet-Durand F, Ekström PA, van Veen T, Leveillard T, Humphries P, Seeliger MW, Bhattacharya SS. Study of gene targeted mouse models of splicing factor gene Prpf31 implicated in human autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5927–5933. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huranova M, Hnilicova J, Fleischer B, Cvackova Z, Stanek D. A mutation linked to retinitis pigmentosa in HPRP31 causes protein instability and impairs its interactions with spliceosomal snRNPs. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2014–2023. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Kawada M, Havlioglu N, Tang H, Wu JY. Mutations in PRPF31 inhibit pre-mRNA splicing of rhodopsin gene and cause apoptosis of retinal cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:748–757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2399-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JY, Dai X, Sheng J. et al. Identification and functional characterization of a novel splicing mutation in RP gene PRPF31. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia K, Zheng D, Pan Q. et al. A novel PRPF31 splice-site mutation in a Chinese family with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2004;367(10):361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakarova CF, Cherninkova S, Tournev I. et al. Molecular genetics of retinitis pigmentosa in two Romani (Gypsy) families. Mol Vis. 2006;12:909–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn L, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS. et al. Breakpoint characterization of a novel approximately 59 kb genomic deletion on 19q13.42 in autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa with incomplete penetrance. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:651–655. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Safieh L, Vithan EN, Mantel I. et al. A large deletion in the adRP gene PRPF31: evidence that haploinsufficiency is the cause of disease. Mol Vis. 2006;12:384–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]