Abstract

Background

H-NS regulates the acid stress resistance. The present study aimed to characterize the H-NS-dependent cascade governing the acid stress resistance pathways and to define the interplay between the different regulators.

Results

We combined mutational, phenotypic and gene expression analyses, to unravel the regulatory hierarchy in acid resistance involving H-NS, RcsB-P/GadE complex, HdfR, CadC, AdiY regulators, and DNA-binding assays to separate direct effects from indirect ones. RcsB-P/GadE regulatory complex, the general direct regulator of glutamate-, arginine- and lysine-dependent acid resistance pathways plays a central role in the regulatory cascade. However, H-NS also directly controls specific regulators of these pathways (e.g. cadC) and genes involved in general stress resistance (hdeAB, hdeD, dps, adiY). Finally, we found that in addition to H-NS and RcsB, a third regulator, HdfR, inversely controls glutamate-dependent acid resistance pathway and motility.

Conclusions

H-NS lies near the top of the hierarchy orchestrating acid response centred on RcsB-P/GadE regulatory complex, the general direct regulator of glutamate-, arginine- and lysine-dependent acid resistance pathways.

Background

In Escherichia coli, complex cellular responses are controlled by networks of transcriptional factors that regulate the expression of a diverse set of target genes, at various hierarchical levels. H-NS, a nucleoid-associated protein, is a top level regulator affecting the expression of at least 250 genes, mainly related to the bacterial response to environmental changes [1]. Among its various targets, it regulates in opposite directions the flagella-dependent motility and the acid stress resistance [1]; the first via the control of flhDC master flagellar operon by acting both directly and indirectly via regulators HdfR and RcsB [2-6]; the second by repressing the genes involved in three amino acid decarboxylase systems, dependent on glutamate, lysine and arginine, via the RcsB-P/GadE regulatory complex [6]. In this regulatory process H-NS represses the expression of gadE (encoding the central activator of the glutamate-dependent acid resistance pathway) both in a direct and an indirect way, via EvgA, YdeO, GadX and GadW [1,7,8], while it decreases rcsD expression, essential to the phosphorylation of RcsB (the capsular synthesis regulator component) required for the formation of the regulatory complex with GadE [6]. In the glutamate pathway, the RcsB-P/GadE regulatory complex controls the expression of two glutamate decarboxylase paralogues GadA and GadB, the glutamate/gamma-aminobutyrate antiporter GadC, two glutamate synthase subunits GltB and GltD, the acid stress chaperones HdeA and HdeB, the membrane protein HdeD, the transcriptional regulator YhiF (DctR) and the outer membrane protein Slp [6]. The complex also induces an arginine decarboxylase, AdiA, and an arginine:agmatine antiporter, AdiC (YjdE), essential for arginine-dependent acid resistance. Finally, the complex regulates a lysine decarboxylase, CadA, and a cadaverine/lysine antiporter, CadB, essential for lysine-dependent acid resistance [1,6,9]. Apart from the gadBC operon, the most important genes involved in acid resistance are present within the acid fitness island (AFI), a 15 kb region both repressed by H-NS and under the control of RpoS [10,11]. Recent global chromatin immunoprecipitation studies revealed that H-NS binds to several loci within this region, including hdeABD [12,13]. However, neither AdiY, the main regulator of the arginine-dependent response that controls adiA and adiC expression [14,15] nor CadC, the main regulator of lysine-dependent response controlling cadBA [16], were yet found among the identified H-NS targets.

In the present study, we aimed at further characterizing the H-NS-dependent cascade governing acid stress resistance pathways to identify the missing intermediary regulator(s) or functional protein(s) controlled by H-NS and to define the interplay between the different regulators and their targets.

Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Mutants were constructed by replacing the entire gene of interest with an antibiotic cassette using the CF10230 strain, as previously described [17]. These mutations, as well as their Miki and Keio collection counterparts from NBRP (NIG, Japan): E. coli [18,19] were subsequently transduced into FB8 hns::Sm derivative strains, using P1vir phage. When required, antibiotics were added: ampicillin (100 μg ml-1), streptomycin (10 μg ml-1), kanamycin (40 μg ml-1), tetracycline (15 μg ml-1).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| JD21162 | KP7600 (F- lacIQ lacZdeltaM15 galK2 galT22 lambda- in (rrnD-rrnE)1, W3110 derivative) ydeP ::Km | [19] |

| JD24946 | KP7600 (F- lacIQ lacZdeltaM15 galK2 galT22 lambda- in (rrnD-rrnE)1, W3110 derivative) yhiM ::Km | [19] |

| JD25275 | KP7600 (F- lacIQ lacZdeltaM15 galK2 galT22 lambda- in (rrnD-rrnE)1, W3110 derivative) hdeA ::Km | [19] |

| JD26576 | KP7600 (F- lacIQ lacZdeltaM15 galK2 galT22 lambda- in (rrnD-rrnE)1, W3110 derivative) ydeO::Km | [19] |

| JD27509 | KP7600 (F- lacIQ lacZdeltaM15 galK2 galT22 lambda- in (rrnD-rrnE)1, W3110 derivative) dps ::Km | [19] |

| JW5594 | BW25113 (rrnB ΔlacZ4787 HsdR514 Δ(araBAD)567 Δ(rhaBAD)568 rph-1) ΔaslB ::Km | [18] |

| JW2366 | BW25113 (rrnB ΔlacZ4787 HsdR514 Δ(araBAD)567 Δ(rhaBAD)568 rph-1) ΔevgA ::Km | [18] |

| EP247 | W3110 cadC1::Tn10 | [41] |

| FB8 | Wild type | [42] |

| BE1411 | FB8 hns::Sm | [43] |

| BE2823 | FB8 hns::Sm ΔrcsB ::Km | [6] |

| BE2825 | FB8 hns::Sm ΔhdfR ::Tet | This study |

| BE2826 | FB8 hns::Sm dps ::Km | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 JD27509 |

| BE2827 | FB8 hns::Sm rpoS 359 ::Km | This study |

| BE2828 | FB8 hns::Sm yhiM ::Km | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 JD24946 |

| BE2829 | FB8 hns::Sm ΔevgA ::Km | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 JW2366 |

| BE2830 | FB8 hns::Sm ΔaslB ::Km | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 JW3772 |

| BE2831 | FB8 hns::Sm ydeP ::Km | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 JD21162 |

| BE2832 | FB8 hns::Sm ydeO ::Km | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 JD26576 |

| BE2836 | FB8 hns::Sm ΔhdeA ::Km | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 JD25275 |

| BE2837 | FB8 hns::Sm ΔadiY ::Tet | This study |

| BE2939 | FB8 hns::Sm cadC1::Tn10 | FB8 hns::Sm × P1 EP247 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDIA640 | pet22b ::hdfR with C terminal His tag | This study |

| pDIA642 | pet16b ::rcsBD56E with N terminal His tag | [6] |

| pDIA645 | pet22b ::gadE with C terminal His tag | [6] |

| pDIA646 | pet16b ::adiY with N terminal strep tag | This study |

Resistance to low pH

The experiment was performed at least twice, as previously described [6].

RNA preparation and Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

The experiment was performed twice, as previously described [6]. Primers used in real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments are listed in Additional file 1.

Protein purification

H-NS-His6 was purified as previously described [20]. Recombinant proteins HdfR-His6, His6-RcsBD56E, GadE-His6 and Strep-AdiY were purified as previously described [6].

Gel mobility shift assays

Gel shift assays were performed with 0.1 ng [γ32P]-labelled probe DNA with purified HdfR-His6, His6-RcsBD56E (mimicking phosphorylated and activated RcsB), GadE-His6 and Strep-AdiY proteins as previously described [6,10]. For competitive gel mobility shift assays with purified H-NS protein 100-200 ng PCR fragments of target promoter regions and 270-200 ng of competitor DNA fragments, obtained by digestion of pBR322 plasmid with TaqI and SspI restriction enzymes, were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with H-NS in the previously described reaction mixture [21]. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on 3% or 4% MetaPhor agarose gel. Primers used in gel mobility shift assays are listed in Additional file 2.

Results

Determination of new H-NS targets involved in the regulation of glutamate-dependent acid resistance

As H-NS strongly represses the glutamate-dependent acid stress response, there is a very low level of survival after acid stress in the FB8 wild-type context [6]. As a consequence, H-NS targets involved in this process are only expressed when hns is removed. To find further H-NS-dependent intermediary actors of glutamate-dependent acid resistance, several of the H-NS induced targets, identified in a previous transcriptome analysis [1] and related either to acid stress resistance or to information pathways, were deleted in an hns-deficient strain. We looked for a decreased glutamate-dependent acid resistance, in comparison to that displayed in the parent hns-deficient strain. Different extent of decrease in resistance to acidic conditions was observed with deletion of several genes known to be related to acid stress response including dps (coding for the Dps protein - DNA-binding protein of starved cells), rpoS (coding for the RNA polymerase sigma-38 factor), yhiM (coding for an inner membrane protein), evgA (coding for a transcriptional activator), ydeP (coding for a putative anaerobic dehydrogenase) and ydeO (coding for a transcriptional regulator, which is a target of sRNA OxyS) (Table 2), suggesting a role in the H-NS-controlled glutamate-dependent acid resistance. Furthermore, a reduced resistance was also observed with genes, not previously associated with acid stress, such as aslB (coding for an anaerobic sulfatase-maturating enzyme homolog) and hdfR (coding for the H-NS-dependent flhDC regulator) (Table 2). However, the single deletion of several genes including evgA, ydeP, ydeO and aslB in hns background only slightly affected the acid stress survival, suggesting their redundant function in this H-NS-dependent process.

Table 2.

Glutamate-dependent acid resistance of E. coli strains

| Strain (relevant genotype) | Glutamate-dependent acid resistance (% survival) |

|---|---|

| FB8 (wild-type) | 0.1 |

| BE1411 (hns::Sm) | 51.7 |

| BE2823 (hns::Sm ΔrcsB) | < 0.001 |

| BE2825 (hns::Sm ΔhdfR) | 12.5 |

| BE2826 (hns::Sm dps::Km) | 20.1 |

| BE2827 (hns::Sm rpoS) | 27.5 |

| BE2828 (hns::Sm yhiM::Km) | 24.2 |

| BE2829 (hns::Sm ΔevgA) | 32.0 |

| BE2831 (hns::Sm ydeP::Km) | 35.6 |

| BE2832 (hns::Sm ydeO::Km) | 38.2 |

| BE2830 (hns::Sm ΔaslB) | 38.6 |

| BE2837 (hns::Sm ΔadiY) | 5.4 |

| BE2939 (hns::Sm cadC1::Tn10) | 58.1 |

Data are the mean values of two independent experiments that differed by less than 20%.

Determination of H-NS targets involved in arginine and/or lysine-dependent acid resistance

We wondered whether the new genes identified as H-NS-controlled, but unrelated to regulation by the RcsB-P/GadE complex, also play a role in the arginine and lysine-dependent acid resistance pathways. We performed acid stress assays in the presence of these amino acids with hns-deficient strains also deleted in these genes. Only the deletion of dps led to dramatically low survival rate in the presence of arginine and lysine, while the deletion of hdeA resulted in a 5-fold decreased survival rate in the presence of arginine and slightly modified survival rate in the presence of lysine (Table 3). Although the arginine and lysine-dependent acid resistance pathways are regulated by H-NS [1], it is not known whether AdiY and CadC, the specific regulators of these pathways respectively, are controlled by H-NS. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments were carried out on adiY and cadC with RNA isolated from FB8 wild-type and hns-deficient strains. We observed that the adiY and cadC RNA level increased five-fold in the hns mutant (Table 4), suggesting that they may mediate the effect of H-NS on arginine and lysine-dependent acid stress resistance. To further investigate the role of adiY and cadC in the H-NS-dependent control of acid resistance, each gene was deleted in an hns background and the acid resistance assays were performed in the presence of arginine, glutamate and lysine. In the absence of adiY, much fewer bacteria survived in the presence of glutamate and arginine, but not in the presence of lysine, while the cadC deletion led to extreme acid stress sensitivity only in the presence of lysine (Table 2 and 3). This suggests a role of CadC regulator in the H-NS regulation of the lysine-dependent acid stress resistance and a role of AdiY regulator in the arginine- and glutamate-dependent pathways.

Table 3.

Arginine and lysine-dependent acid resistance of E. coli strains

| Strain (relevant genotype) | Arginine-dependent acid resistance (% survival) |

Lysine-dependent acid resistance (% survival) |

|---|---|---|

| FB8 (wild-type) | 0.23 | 0.05 |

| BE1411 (hns::Sm) | 24.50 | 7.64 |

| BE2823 (hns::Sm ΔrcsB) | 4.44 | 1.00 |

| BE2826 (hns::Sm Δdps) | 0.11 | 0.28 |

| BE2836 (hns::Sm ΔhdeA) | 5.11 | 5.37 |

| BE2837 (hns::Sm ΔadiY) | 1.80 | 7.30 |

| BE2939 (hns::Sm cadC1::Tn10) | 24.24 | 0.001 |

Percentage survival is calculated as 100 × number of c.f.u. per ml remaining after 2 hours low pH treatment in the presence of arginine or lysine, divided by the initial c.f.u. per ml at time zero. Data are the mean values of two independent experiments that differed by less than 15%.

Table 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis on H-NS targets involved in acid stress resistance

| Expression ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | hns/wild-type | hns gadE/wild-type | hns rcsB/wild-type | hns hdfR/wild-type | hns adiY/wild-type |

| Glutamate-dependent specific pathway | |||||

| gadA1 | 137.21 | nd | Nd | 150.93 | 41.31 |

| dctR1 | 34.66 | nd | Nd | 34.32 | 8.84 |

| yhiM | 10.75 | 3.41 | 3.40 | 10.90 | 11.36 |

| aslB | 12.92 | 0.66 | 1.10 | 0.69 | 1.32 |

| gltD1 | 1.68 | nd | Nd | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| Arginine-dependent specific pathway | |||||

| adiA | 16.89 | nd | Nd | nd | 0.70 |

| adiC | 11.62 | nd | Nd | nd | 1.41 |

| Lysine-dependent specific pathway | |||||

| cadC | 4.62 | 5.77 | 6.38 | nd | nd |

| General acid stress resistance pathway | |||||

| hdeA1 | 32.37 | nd | Nd | 41.20 | 6.55 |

| hdeD | 18.96 | nd | Nd | 17.57 | 5.89 |

| adiY | 5.08 | 5.00 | 5.00 | nd | nd |

nd: non-determined.

1: Since several genes are organized in operon and/or are highly homologous to each other, results obtained with gadA also corresponds to gadBC; with gltD to gltB; with hdeA to hdeB; with dctR to slp.

Quantitative RT-PCR were performed on total RNA isolated from exponential growth phase cultures. Standard deviations were less than 20% of the mean.

Identification of the target genes for major regulators

To decipher the regulatory hierarchy in acid stress resistance involving several new H-NS controlled regulators, the mRNA level of target genes was compared between wild-type and hns, hns rcsB, hns gadE, hns hdfR, hns adiY mutant strains, using real-time quantitative RT-PCR (Table 4). In particular, we compared the expression ratio between a double mutant and the wild-type strain with that for hns-deficient and the wild-type strain. H-NS having negative effect on target genes, these genes are strongly derepressed in hns mutant in comparison with wild-type strain. If this strong H-NS repressive effect is abolished in the absence of a regulator negatively controlled by H-NS, we can conclude that this deleted regulator has positive effect on target gene expression and may be an intermediary actor in H-NS-dependent control for this target, as previously shown [6].

It was found that RcsB and GadE upregulate, at the similar level, newly identified genes involved in acid stress resistance pathways dependent on glutamate (yhiM and aslB), but these two regulators did not affect the expression of regulatory genes, cadC and adiY (Table 4). Neither RcsB nor GadE controlled hdfR regulatory gene expression (data not shown), suggesting that the hdfR is not the target of RcsB-P/GadE complex. We found that HdfR controlled only the expression of aslB and gltBD in the glutamate-dependent acid stress resistance regulon (Table 4). As expected, AdiY strongly affected adiA and adiC expression, and also the expression of some genes related to the glutamate specific pathway (aslB, gadA, gadBC, gltBD, and slp-dctR) and to general acid resistance (hdeAB and hdeD) (Table 4). These results demonstrated a multiple control of several target genes involving different regulators acting independently from each other.

Identification of the new targets directly controlled by RcsB-P/GadE complex

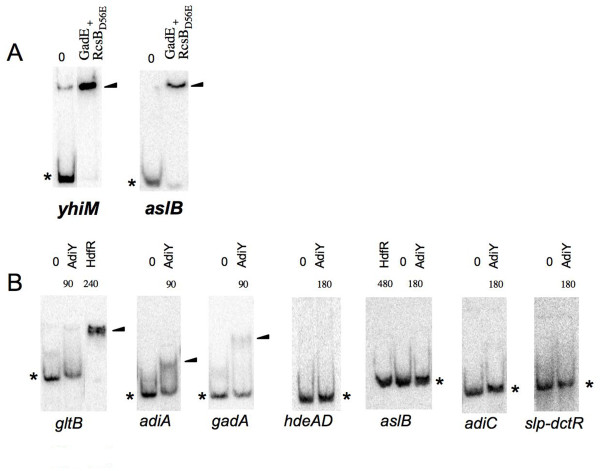

Gel mobility shift assays were performed with a mixture of purified RcsBD56E and GadE proteins to know whether the regulatory complex directly controlled yhiM and aslB. It was established that the RcsBD56E/GadE regulatory complex binds to the promoter regions of the two genes (Figure 1A), demonstrating the direct control by the RcsB-P/GadE complex.

Figure 1.

Gel mobility shift assays with GadE/RcsBD56E complex, HdfR and AdiY. A. Gel mobility shift assays with GadE/RcsBD56E complex and new DNA targets. Proteins were incubated with DNA targets during 30 min at 25°C in the final reaction mixture volume of 15 μl. 900 ng of each GadE and RcsBD56E protein are used for yhiM and aslB. B. Gel mobility shift assays with HdfR or AdiY proteins. Quantities of purified HdfR or AdiY proteins are indicated above each lane (in ng). Gel mobility shift assays (A and B) were performed with 0.1 ng [γ32P]-labelled DNA fragment and loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide native gel. An arrow points out the position of the DNA-regulatory protein complex. An asterisk marks the position of the unbound probe.

Identification of the targets directly controlled by HdfR or AdiY

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that HdfR regulates aslB and gltBD, while AdiY regulates several genes involved in acid stress resistance (adiA, adiC, aslB, gadA, gadBC, gltBD, hdeAB, hdeD and slp-dctR) (Table 4). To establish whether these regulators control the expression of these genes by direct binding to their promoter regions, gel mobility shift assays were performed with purified HdfR and AdiY proteins. It was found that HdfR binds to the promoter region of gltBD and that AdiY binds to the promoter regions of gltBD, adiA and gadABC (Figure 1B). However, no band shift was observed even with higher concentration of regulator with HdfR on the promoter region of aslB and with AdiY on the promoter regions of adiC, aslB, hdeABD and slp-dctR (Figure 1B), suggesting an indirect regulation for these genes.

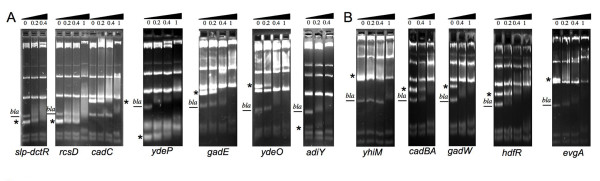

Identification of the targets directly controlled by H-NS

H-NS modulates the expression of several regulators controlling acid stress resistance including HdfR, RcsD, EvgA, YdeO, YdeP, GadE, GadW, GadX, AdiY and CadC. However, the direct control by H-NS has not yet been established for the majority of these regulators, except for GadX [22] and HdfR [3]. Furthermore, slp-dctR and yhiM could also be directly repressed by H-NS, as deletion of their regulators, RcsB-P/GadE complex and/or AdiY, in hns-deficient strain was not sufficient to restore their wild-type mRNA level (Table 4) [6]. Competitive gel mobility shift assays were performed with purified H-NS protein on PCR fragments, corresponding to assayed promoters, and restriction fragments derived from the pBR322 plasmid, used as negative competitors for binding to H-NS protein except for one 217-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the bla promoter used as positive internal control [21]. A preferential binding of H-NS was observed to the promoter regions of adiY, cadBA, cadC, evgA, gadE, gadW, hdfR, rcsD, slp-dctR, ydeO, ydeP, yhiM, confirming the direct control by H-NS of these genes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Competitive gel mobility shift assay with H-NS, target promoter fragments and restriction fragments derived from plasmid pBR322. The cleaved plasmid and promoter fragments were incubated with the indicated concentrations of purified H-NS protein (in μM). After protein-DNA complex formation, the fragments were resolved on a 3% (A) or 4% (B) MetaPhor agarose gel. An asterisk indicates the position of the target promoter fragments. "bla" indicates the bla promoter (positive control), the other fragments of plasmid DNA correspond to negative controls. The specific binding of H-NS is observed when bands corresponding to bla and target promoter disappear with increasing concentration of H-NS, the H-NS-DNA complex being difficult to visualize under these conditions.

Discussion

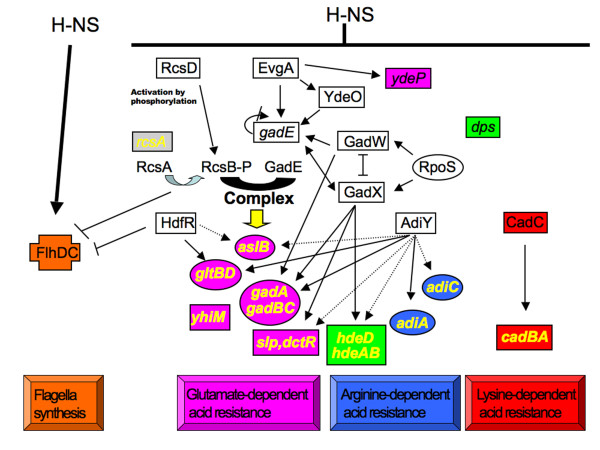

H-NS regulates directly and indirectly the RcsB-P/GadE complex, that is located at the centre of the acid resistance network as well as control of motility (Figure 3). Furthermore, H-NS modulates the level of several regulatory proteins, unrelated to this complex (e.g. CadC, AdiY, HdfR) (Table 4 and Figure 2) [3]. Among them, only HdfR was previously known as a H-NS target [3]. The present study revealed that, in addition to its role in motility control, HdfR regulates the glutamate-dependent acid resistance pathway, directly inducing gltBD and indirectly controlling aslB (Table 4 and Figure 1, 3). All the results presented in this work were integrated together with previously published data, to propose a model of the complex H-NS-dependent regulatory network governing motility and acid stress resistance processes in E. coli (Figure 3). The new characterized H-NS targets, CadC and AdiY, have no effect on motility (data not shown) and are involved in the H-NS-dependent regulation of lysine and arginine-dependent response to acid stress, respectively (Table 3). Furthermore, we found that AdiY is also involved in glutamate-dependent response to acid stress (Table 2). It directly or indirectly regulates several genes specific to this response including aslB, gltBD, gadA, gadBC, slp-dctR or having more global role in acid stress resistance such as hdeAB and hdeD (Table 4). Interestingly, we demonstrated that H-NS has a direct control effect on the cadBA promoter (Figure 2), in accordance with the previous suggestion of a competition between the CadC activator and H-NS for binding to this promoter region [23]. In addition to its role in the repression of major regulators at high levels of the hierarchy, we have shown that H-NS is able to directly affect acid stress circuits repressing the transcription of several structural genes (e.g. yhiM, slp, dctR) (Figure 2). This is in agreement with the proposed competition between activation by specific regulators and repression by H-NS, in several bacterial systems [24,25]. The results of present study point out the essential role for several intermediary players within H-NS-dependent regulatory network and suggest an accessory role for other regulators in acid stress response. Indeed, the EvgA-YdeO regulatory pathway plays a secondary modulator role in the glutamate-dependent acid stress response, in comparison to H-NS. In the same means, AslB and YdeP, two anaerobic enzymes, may have a redundant function in this stress response.

Figure 3.

Model of the H-NS-dependent regulatory network in flagella and acid stress control. At the top, H-NS positively controls motility and represses acid stress resistance. Genes in cross symbol are directly activated by H-NS; in rectangle: directly repressed by H-NS; in circle: indirectly repressed by H-NS. Regulatory proteins are indicated with upper case. Orange filling: flagellum synthesis process; Pink filling: glutamate-dependent acid resistance process; Blue filling: arginine-dependent acid resistance process; Red filling: lysine-dependent acid resistance process; Green filling: genes involved in three different acid resistance processes. Gene names in yellow indicate the direct targets of RcsB-P/GadE complex placed at the centre of this regulatory cascade. A positive effect on transcription is indicated by arrows and a negative regulatory effect is indicated by blunt ended lines. Direct regulation is indicated by solid lines. Indirect regulation is indicated by dashed lines. Previously published results are included in the scheme: [1-3,5-7,10,16,32-40].

Among the H-NS-regulated genes, we showed that the acid stress chaperones HdeA and HdeB that solubilized periplasmic protein aggregates at acid pH [26] are involved in all three pathways of acid stress response. However, their impact is low in the arginine- and lysine-dependent pathways (Table 3), while they are essential in the glutamate-dependent pathway [27]. This could be explained by the fact that arginine and lysine amino acids are able to strongly oppose protein aggregation [28]. By contrast, we found that the expression of the dps gene, directly regulated by H-NS and known to protect cells against multiple stresses [29], is essential to lysine- and arginine-dependent responses to acid stress, while its role is less important during the glutamate-dependent response (Table 2 and 3). This implies that the induced glutamate-dependent response provides sufficient cell protection, restricting Dps to a marginal role. This is consistent with the observation that glutamate is widely distributed amino acid representing approximately 15--45% in the dietary protein content and plays a key physiological role in gastrointestinal tract [30].

Within this frame of thought, the glutamate decarboxylase system would be the most efficient acid resistance mechanism [31]. This could also explain why three regulators H-NS, HdfR and RcsB are directly involved in the control of both glutamate-dependent acid stress response and the flagellum biosynthesis. Indeed, as flagellum is a high consumer of ATP and leads to proton entrance during its motor functioning, it is necessary to stop this process to limit cytoplasmic acidification in bacteria and to redirect energy to mechanisms of resistance to stress. Furthermore, the flagellar filaments bear strong antigenic properties in contact with host. We can suppose that these complex high-organized regulations allow a faster adaptation to environmental variations and an increase in survival under adverse conditions found in gastric environment contributing to the virulence of gastrointestinal bacteria, examplified by enteroinvasive E. coli HN280 [32].

Conclusion

In E. coli, the control of acid stress resistance is achieved by the concerted efforts of multiple regulators and overlapping systems, most of the genes directly involved in acid resistance being both controlled by RcsB-P/GadE complex and by at least one other regulator such as H-NS, HdfR, CadC or AdiY.

Authors' contributions

EK conceived the study, performed all experiments and drafted the manuscript. AD helped to finalize the manuscript and to place it in perspective, OS helped to analyse the data and to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

List of primers used in real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments.

List of primers used for gels retardation assay.

Contributor Information

Evelyne Krin, Email: ekrin@pasteur.fr.

Antoine Danchin, Email: antoine.danchin@normalesup.org.

Olga Soutourina, Email: osoutou@pasteur.fr.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nathalie Sassoon for help in protein purifications and Zeynep Baharoglu for critical reading of the manuscript. Financial support came from the Institut Pasteur, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (URA 2171) and the Probactys NEST European programme, grant CT-2006-029104. OS is assistant professor at the Université Paris 7.

References

- Hommais F, Krin E, Laurent-Winter C, Soutourina O, Malpertuy A, Le Caer JP, Danchin A, Bertin P. Large-scale monitoring of pleiotropic regulation of gene expression by the prokaryotic nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40(1):20–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francez-Charlot A, Laugel B, Van Gemert A, Dubarry N, Wiorowski F, Castanie-Cornet MP, Gutierrez C, Cam K. RcsCDB His-Asp phosphorelay system negatively regulates the flhDC operon in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49(3):823–832. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko M, Park C. H-NS-Dependent regulation of flagellar synthesis is mediated by a LysR family protein. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(16):4670–4672. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.16.4670-4672.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutourina O, Kolb A, Krin E, Laurent-Winter C, Rimsky S, Danchin A, Bertin P. Multiple control of flagellum biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: role of H-NS protein and the cyclic AMP-catabolite activator protein complex in transcription of the flhDC master operon. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(24):7500–7508. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7500-7508.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutourina OA, Krin E, Laurent-Winter C, Hommais F, Danchin A, Bertin PN. Regulation of bacterial motility in response to low pH in Escherichia coli: the role of H-NS protein. Microbiology. 2002;148(5):1543–1551. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-5-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krin E, Danchin A, Soutourina O. RcsB plays a central role in H-NS-dependent regulation of motility and acid stress resistance in Escherichia coli. Res Microbiol. 2010;161(5):363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda N, Church GM. Regulatory network of acid resistance genes in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48(3):699–712. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed AK, Odom C, Foster JW. The Escherichia coli AraC-family regulators GadX and GadW activate gadE, the central activator of glutamate-dependent acid resistance. Microbiology. 2007;153(8):2584–2592. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlung T, Ingmer H. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24(1):7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3151679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommais F, Krin E, Coppee JY, Lacroix C, Yeramian E, Danchin A, Bertin P. GadE (YhiE): a novel activator involved in the response to acid environment in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2004;150(1):61–72. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H, Polen T, Heuveling J, Wendisch VF, Hengge R. Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: sigmaS-dependent genes, promoters, and sigma factor selectivity. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(5):1591–1603. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1591-1603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, Song M, Rhee JH, Hong Y, Kim YJ, Seok YJ, Ha KS, Jung SH, Choy HE. DNA looping-mediated repression by histone-like protein H-NS: specific requirement of Esigma70 as a cofactor for looping. Genes Dev. 2005;19(19):2388–2398. doi: 10.1101/gad.1316305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima T, Ishikawa S, Kurokawa K, Aiba H, Ogasawara N. Escherichia coli histone-like protein H-NS preferentially binds to horizontally acquired DNA in association with RNA polymerase. DNA Res. 2006;13(4):141–153. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsl009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieboom J, Abee T. Arginine-dependent acid resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(15):5650–5653. doi: 10.1128/JB.00323-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stim-Herndon KP, Flores TM, Bennett GN. Molecular characterization of adiY, a regulatory gene which affects expression of the biodegradative acid-induced arginine decarboxylase gene (adiA) of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1996;142:1311–1320. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell CL, Neely MN, Olson ER. Altered pH and lysine signalling mutants of cadC, a gene encoding a membrane-bound transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli cadBA operon. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14(1):7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechold U, Ogryzko V, Ngo S, Danchin A. Oligoribonuclease is a common downstream target of lithium-induced pAp accumulation in Escherichia coli and human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(8):2364–2373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:2006 0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Yamamoto Y, Matsuda H. A novel, simple, high-throughput method for isolation of genome-wide transposon insertion mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;416:195–204. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-321-9_13. full_text. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RM, Rimsky S, Buc H. Probing the structure, function, and interactions of the Escherichia coli H-NS and StpA proteins by using dominant negative derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(15):4335–4343. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4335-4343.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyard S, Bertin P. Characterization of BpH3, an H-NS-like protein in Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24(4):815–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3891753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangrossi M, Zattoni S, Tramonti A, De Biase D, Falconi M. Antagonistic role of H-NS and GadX in the regulation of the glutamate decarboxylase-dependent acid resistance system in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(22):21498–21505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper C, Jung K. CadC-mediated activation of the cadBA promoter in Escherichia coli. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;10(1):26–39. doi: 10.1159/000090346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman CJ. H-NS, the genome sentinel. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(2):157–161. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang FC, Rimsky S. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(2):113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malki A, Le HT, Milles S, Kern R, Caldas T, Abdallah J, Richarme G. Solubilization of protein aggregates by the acid stress chaperones HdeA and HdeB. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(20):13679–13687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman SR, Small PL. Identification of sigma S-dependent genes associated with the stationary-phase acid-resistance phenotype of Shigella flexneri. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21(5):925–940. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau F, Serrano L, Schymkowitz JW. How evolutionary pressure against protein aggregation shaped chaperone specificity. J Mol Biol. 2006;355(5):1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S, Finkel SE. Dps protects cells against multiple stresses during stationary phase. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(13):4192–4198. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4192-4198.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura E, Torii K, Uneyama H. Physiological roles of dietary free glutamate in gastrointestinal functions. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31(10):1841–1843. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gut H, Pennacchietti E, John RA, Bossa F, Capitani G, De Biase D, Grutter MG. Escherichia coli acid resistance: pH-sensing, activation by chloride and autoinhibition in GadB. EMBO J. 2006;25(11):2643–2651. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna B, Casalino M, Fradiani PA, Zagaglia C, Naitza S, Leoni L, Prosseda G, Coppo A, Ghelardini P, Nicoletti M. H-NS regulation of virulence gene expression in enteroinvasive Escherichia coli harboring the virulence plasmid integrated into the host chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(16):4703–4712. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4703-4712.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MH, Takeda S, Yamada H, Ishii Y, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. Characterization of the RcsC--> YojN-- > RcsB phosphorelay signaling pathway involved in capsular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65(10):2364–2367. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger DC, Goldberg MD, Lee DJ, Busby SJ. Selective repression by Fis and H-NS at the Escherichia coli dps promoter. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68(6):1366–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itou J, Eguchi Y, Utsumi R. Molecular mechanism of transcriptional cascade initiated by the EvgS/EvgA system in Escherichia coli K-12. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73(4):870–878. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Richard H, Tucker DL, Conway T, Foster JW. Collaborative regulation of Escherichia coli glutamate-dependent acid resistance by two AraC-like regulators, GadX and GadW (YhiW) J Bacteriol. 2002;184(24):7001–7012. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.7001-7012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramonti A, De Canio M, Delany I, Scarlato V, De Biase D. Mechanisms of transcription activation exerted by GadX and GadW at the gadA and gadBC gene promoters of the glutamate-based acid resistance system in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(23):8118–8127. doi: 10.1128/JB.01044-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramonti A, Visca P, De Canio M, Falconi M, De Biase D. Functional characterization and regulation of gadX, a gene encoding an AraC/XylS-like transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli glutamic acid decarboxylase system. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(10):2603–2613. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.10.2603-2613.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker DL, Tucker N, Ma Z, Foster JW, Miranda RL, Cohen PS, Conway T. Genes of the GadX-GadW regulon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(10):3190–3201. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.10.3190-3201.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Gottesman S. Modes of regulation of RpoS by H-NS. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(19):7022–7025. doi: 10.1128/JB.00687-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely MN, Dell CL, Olson ER. Roles of LysP and CadC in mediating the lysine requirement for acid induction of the Escherichia coli cad operon. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(11):3278–3285. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3278-3285.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni CB, Colantuoni V, Sbordone L, Cortese R, Blasi F. Biochemical and regulatory properties of Escherichia coli K-12 hisT mutants. J Bacteriol. 1977;130(1):4–10. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.4-10.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin P, Benhabiles N, Krin E, Laurent-Winter C, Tendeng C, Turlin E, Thomas A, Danchin A, Brasseur R. The structural and functional organization of H-NS-like proteins is evolutionarily conserved in gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31(1):319–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of primers used in real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments.

List of primers used for gels retardation assay.