Abstract

Autoimmune diseases are chronic disorders initiated by a loss of immunologic tolerance to self-antigens. They cluster within families, and patients may be diagnosed with more than one disease, suggesting pleiotropic genes are involved in the aetiology of different diseases. To identify potential loci, which confer susceptibility to autoimmunity independent of disease phenotype, we pooled results from genome-wide linkage studies, using the genome scan meta-analysis method (GSMA). The meta-analysis included 42 independent studies for 11 autoimmune diseases, using 7350 families with 18 291 affected individuals. In addition to the HLA region, which showed highly significant genome-wide evidence for linkage, we obtained suggestive evidence for linkage on chromosome 16, with peak evidence at 10.0–19.8 Mb. This region may harbour a pleiotropic gene (or genes) conferring risk for several diseases, although no such gene has been identified through association studies. We did not identify evidence for linkage at several genes known to confer increased risk to different autoimmune diseases (PTPN22, CTLA4), even in subgroups of diseases consistently found to be associated with these genes. The relative risks conferred by variants in these genes are modest (<1.5 in most cases), and even a large study like this meta-analysis lacks power to detect linkage. This study illustrates the concept that linkage and association studies have power to identify very different types of disease-predisposing variants.

Keywords: genetics, pleiotropy

Introduction

Autoimmune diseases are common disorders, affecting around 5–10% of the population, with female subjects generally having a higher disease incidence than male subjects.1 Evidence for genetic contributions is strong, with increased concordance rates observed in monozygotic twins (ranging from 30–70%) when compared with dizygotic twins.2 A feature of these disorders is their tendency to co-occur in the same individuals and in families. For example, a cluster of rheumatoid arthritis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and autoimmune thyroid disease has long been recognized.3 Further, shared susceptibility loci identified for different diseases have also been observed,4 supporting the hypothesis that clinically distinct disorders share a common genetic background controlled by pleiotropic susceptibility genes. In support of a shared genetic basis, genes in three regions have been consistently associated with multiple autoimmune diseases: the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II region on chromosome 6p21, the gene encoding cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated 4 (CTLA4) on chromosome 2q33 and the PTPN22 gene encoding lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase on chromosome 1p13,5 although the role of these genes in some diseases remains unclear.

Genome-wide association studies for autoimmune diseases are identifying novel genes that were not previously considered as candidates, and genes with effects that would be difficult to detect in linkage studies.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Meanwhile, much effort has been expended in family collections and genotyping of linkage studies, and it is therefore valuable to extract all possible information from these resources. In this study, we present a meta-analysis of all genome-wide linkage screens performed on autoimmune diseases, using the genome scan meta-analysis (GSMA) method.12 GSMA is a widely used approach to combine linkage results from non-overlapping studies, and has previously been applied to many diseases, including specific autoimmune diseases.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 In this study, we analysed 42 independent studies with complete genome-wide results in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), juvenile RA (JRA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis, IBD), psoriasis (PS), autoimmune thyroid disease (Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease, AITD), vitiligo (VIT), multiple sclerosis (MS), type 1 diabetes (T1D) and celiac disease (CD). We also investigated linkage to various clusters, such as diseases associated with PTPN22 or CTLA4 and diseases found to co-occur more frequently in the same families or patients.

Materials and methods

We identified all published genome-wide linkage studies performed in any autoimmune disease using Medline and PubMed searches. Genome-wide association studies were excluded, as were candidate region and follow-up linkage studies, which considered only specific regions of the genome. Linkage studies overlapping in patient samples, or extended versions of previous publications were identified, and only independent and most recent studies were included. Where studies had performed a two-stage analysis, genotyping markers in targeted regions in the second stage, only the first stage results were used, as the GSMA requires a uniform distribution of markers and families across the genome. Finally, linkage studies performed on single consanguineous families, usually from isolates or specific ethnic groups, were excluded.

In total, 56 independent genome-wide linkage studies were found. 14 studies were excluded as they presented linkage results only at the most significant regions, which reduces the power of the GSMA.19 The remaining 42 studies with complete genome-wide results were included in the meta-analysis, and comprise 7350 families with 18 291 affected individuals from 11 diseases (Table 1 and Supplementary Table A). Most studies (37 out of 42) used populations of European ancestry, and these were also analysed separately. Results from the X chromosome were available in 29 studies.

Table 1. Summary of the genome-wide linkage studies included in the GSMA for each disease.

| Autoimmune disease | Number of studies | Total number of families | Total number of affecteds | References |

| Type 1 diabetes (T1D) | 1 | 1435 | 3109 | 20 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | 9 | 1257 | 3096 | 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 |

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) | 7 | 1144 | 2485 | 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 |

| Autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD) | 3 | 773 | 2476 | 37, 38, 39 |

| Psoriasis (PS) | 7 | 703 | 2333 | 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | 4 | 928 | 1976 | 47, 48, 49, 50 |

| Celiac disease (CD) | 4 | 308 | 965 | 51, 52, 53, 54 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) | 2 | 365 | 869 | 55, 56 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | 3 | 259 | 563 | 57, 58, 59 |

| Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) | 1 | 121 | 247 | 60 |

| Vitiligo (VIT) | 1 | 57 | 172 | 61 |

| Total | 42 | 7350 | 18291 |

GSMA performs meta-analysis pooling results across the genome and does not require individual level genotype data. It is a rank-based meta-analysis method, which assesses the strongest evidence for linkage within prespecified genomic regions, termed bins, usually of 30 cM width. For each study, the maximum linkage statistic within a bin is identified (eg, maximum LOD or NPL score, or minimum P-value). Bins are then ranked, and ranks (or weighted ranks) for each bin are summed across studies, with the summed rank (SR) forming a test statistic. The significance of the SR in each bin is assessed using Monte Carlo simulations, permuting the bin location of ranks within each study, to obtain an empirical P-value. Analysis was performed using the GSMA software (http://www.kcl.ac.uk/mmg/research/gsma/) with 10 000 simulations.62

The traditional 30 cM bin definition gives a total of 118 bins on the autosomes and an additional six bins on the X chromosome, on the basis of the Marshfield genetic map (http://research.marshfieldclinic.org/genetics/home/index.asp).63 To assess how bin width and location affects the significance and localization of linkage signals, we also applied the GSMA using different bin definitions (20 and 40 cM wide, and shifted 30 cM bins obtained by moving bin boundaries by 15 cM).15 To control for multiple testing, we used a Bonferroni correction for the number of bins across the genome: for 30 cM bins, a P-value of 0.05/118=0.00042 was necessary for genome-wide significant evidence of linkage and a P-value of 1/118=0.00847 for suggestive evidence of linkage. Corresponding P-values were calculated for other bin sizes.

We performed both unweighted GSMA analysis (which assumes an equal contribution from each study) and weighted analyses. Three weighting functions were used (Supplementary Table A): firstly, controlling only for study size (wts1, with a weighting factor for each study equal to the square root of the number of affected individuals), secondly controlling partially for the number and size of studies in each disease (wts2, where the sum of the weights for each disease depended on the square root of total number of affected individuals of each disease) and thirdly allowing each disease to contribute equally to the analysis, regardless of the number of studies or their sample size (wts3, using the weighted summed ranks from for each disease). For weighting functions wts2 and wts3, within each disease, studies contributed in proportion to the square root of the total number of affected individuals. An X-chromosome GSMA was performed on the 29 studies for which these results were available. GSMA was performed genome-wide, and then X-chromosome P-values extracted.

We also examined different autoimmune-disease clusters on the basis of identified familial aggregation, defining clusters of T1D+AITD+RA (nine studies) and AITD+SLE+VIT (seven studies,) and on the basis of common pathophysiological characteristics, such as the seronegative spondyloarthropathies group (IBD+PS+AS, 18 studies). Finally, as genetic association provides direct evidence for common aetiological pathways, we considered two clusters of diseases, which show association with PTPN22 (T1D+AITD+RA+SLE+JRA+VIT, 13 studies) and with CTLA4 (T1D+ AITD+CD+SLE, 11 studies), although conflicting evidence has been observed in other autoimmune diseases.64

We estimated the power of linkage studies to identify PTPN22 and CTLA4 at suggestive and genome-wide significance levels, assuming non-parametric linkage analysis with affected sibling pairs.65, 66 For sample size, we used the total number of families in each cluster, as simulation shows that the GSMA has similar power to individual genotyping to detect linkage.67 We extracted genotypic relative risks of the PTPN22 and the CTLA4 risk variants from the literature, and then calculated the locus-specific recurrence risks.

Results

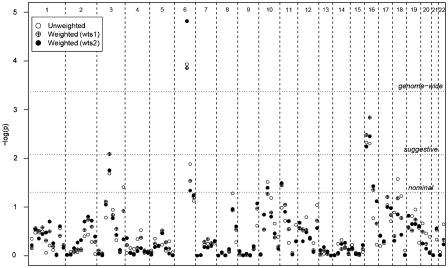

Genetic regions showing at least nominally significant evidence for linkage (P-value<0.05) in the weighted and unweighted meta-analyses of 30 cM bins are shown in Table 2, with weighted (wts1 and wts2) and unweighted results illustrated in Figure 1. No evidence for linkage was detected on chromosome X. As expected, the most significant results were obtained at the HLA region (bin 6_2), with a strong effect also seen in flanking bins (6_1, 6_3, and to some extent in bins 6_4 and 6_5). This linkage evidence in 6q may be a carry-over effect from the HLA region, as multipoint linkage scores can be elevated across 30–50 cM, but we cannot exclude the possibility that it indicates a novel susceptibility locus on chromosome 6q. Although there is considerable variation across diseases in associated alleles/haplotypes and risks conferred,69 strong linkage to HLA in this GSMA was observed, with maximum ranks obtained at bin 6_2 for all diseases, except VIT (showing a rank above the 90th percentile) and AITD (∼75th percentile).

Table 2. Bins showing nominally significant evidence for linkage for all diseases and the PTPN22- and CTLA4-associated disease clusters, using bins of 30 cM widths.

| All autoimmune diseases (42 studies) | PTPN22-associated (13 studies) | CTLA4-associated (11 studies) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighting | — | wts1 | wts2 | wts3 | — | wts1 | — | wts1 | |||

| Chr | Bina | cMb | Mbc | ||||||||

| 1 | 1_9 | 232–261 | 208–235 | — | — | — | — | 0.0298 | 0.0301 | — | — |

| 2 | 2_8 | 209–239 | 213–233 | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0322 | — | — |

| 3 | 3_4 | 86–114 | 63–102 | 0.0205 | 0.0082 | 0.0177 | 0.0475 | — | — | — | 0.0423 |

| 3_8 | 200–228 | 187–199 | 0.0391 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 6 | 6_1 | 0–32 | 0–16 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0011 | 0.0051 |

| 6_2 | 32–64 | 16–42 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 6_3 | 64–97 | 42–89 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | |

| 6_4 | 97–129 | 89–129 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0010 | — | 0.0341 | |

| 6_5 | 129–161 | 129–156 | 0.0132 | 0.0289 | 0.0459 | 0.0037 | — | — | — | — | |

| 6_6 | 161–193 | 156–171 | — | — | — | 0.0180 | — | — | — | — | |

| 8 | 8_5 | 112–140 | 100–129 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0486 | — |

| 10 | 10_2 | 29–58 | 9–30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0394 | 0.0194 |

| 10_3 | 58–87 | 30–69 | 0.0307 | — | 0.0400 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 11 | 11_1 | 0–30 | 0–26 | — | 0.0357 | 0.0319 | — | — | — | — | 0.0182 |

| 12 | 12_6 | 142–171 | 124–132 | — | — | — | — | 0.0319 | — | — | — |

| 14 | 14_3 | 55–83 | 52–74 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0192 | — |

| 14_4 | 83–111 | 74–93 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0103 | 0.0295 | |

| 14_5 | 111–138 | 93–105 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0397 | |

| 16 | 16_1 | 0–34 | 0–18 | 0.0047 | 0.0033 | 0.0058 | 0.0106 | 0.0261 | 0.0218 | — | 0.0275 |

| 16_2 | 34–67 | 18–62 | 0.0050 | 0.0014 | 0.0035 | 0.0220 | 0.0065 | 0.0050 | — | 0.0268 | |

| 16_3 | 67–101 | 62–78 | — | 0.0446 | 0.0372 | — | 0.0418 | 0.0296 | — | — | |

| 16_4 | 101–134 | 78–88 | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0279 | 0.0490 | 0.0144 | |

| 18 | 18_2 | 32–63 | 10–38 | 0.0268 | — | — | — | — | — | 0.0127 | 0.0243 |

Bold, underlined P-values indicate genome-wide evidence of linkage (P<0.00042); bold P-values indicate suggestive evidence of linkage (P<0.00847). ‘—' indicates non-significant.

Bins are labelled chr_bin, so that bin 1_4 indicates the fourth bin on chromosome 1.

On the basis of the Marshfield genetic map.

Corresponding physical intervals were derived from the Mb positions on the basis of the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map (Build 36, http://compgen.rutgers.edu/maps/b36.shtml),68 after matching Marshfield and Rutgers genetic locations.

Figure 1.

Evidence for linkage in meta-analysis of 42 genome-wide linkage studies by chromosome (X-axis). Y-axis shows –log10 (P-value) for unweighted and weighted (wts1 and wts2) summed ranks against bin location (30 cM bins), with a single point plotted for each bin, omitting HLA region showing strong linkage. Thresholds for nominal, suggestive and genome-wide significant evidence for linkage are shown.

On chromosome 16, suggestive evidence for linkage was consistently detected in bins 16_1 and 16_2 for weighting factors wts1, wts2 and for unweighted analysis, with nominal significance for wts3. Further analysis using different bin widths showed suggestive evidence for linkage (Figure 2). The strongest result was obtained with a 20 cM bin (18.1–38.5 cM and 10.0–19.8 Mb); the original 30 cM analysis splits this bin, with a consequent slight reduction in significance for bins 16_1 and 16_2.

Figure 2.

Linkage to chromosome 16 using different bin widths (20 cM, 30 cM and 40 cM) and shifted 30 cM bins for the weighted GSMA (wts2) on 42 studies. The Y-axis is –log10 (P-value) multiplied by the total number of bins, to give consistent thresholds for genome-wide and suggestive evidence for linkage for all bin widths.

On chromosome 3, bin 3_4 attained suggestive significance in the weighted analysis when controlling for the study size (wts1), but only nominal significance in other analyses. We also analysed the studies excluding chromosome 6, to ensure that the assignment of high study ranks to this region was not obscuring linkage elsewhere in the genome. No additional regions reached suggestive evidence for linkage, and only nine bins achieved nominally significant (a non-significant increase compared to 5.6 bins expected by chance). The analyses of only European ancestry studies showed similar evidence for linkage on chromosomes 6, 16 and 3, and failed to identify any novel linked regions.

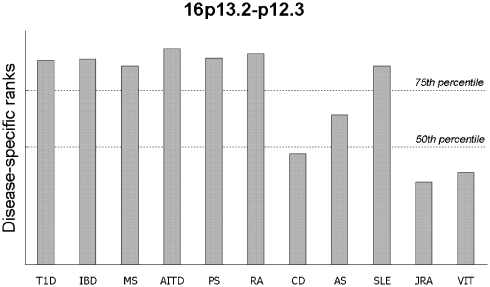

The contribution of each disease to the chromosome 16-linked region in Figure 3 shows that 7 of the 11 diseases attained ranks above the 75th percentile of ranks across the genome, and three diseases (CD, JRA and VIT) had contributions below the 50th percentile, suggesting that this region may harbour a pleiotropic gene (or genes) conferring risk for several, but not all, autoimmune disorders.

Figure 3.

Contribution of each autoimmune disease to the most strongly linked 20 cM bin on 16p13.2-p12.3, with 50 and 75th percentile of ranks for the whole genome shown.

Two clusters showed suggestive evidence of linkage to bin 16_2: the seronegative spondyloarthropathies (IBD, PS and AS), with P-value=0.0046 for weighting factor wts1, and the PTPN22-associated cluster (Table 2). In the seronegative spondyloarthropathies, suggestive evidence for linkage was also detected on chromosome 3 (bins 3_4 and 3_8, P-value=0.0025 and 0.0010, with wts1) and in AITD-SLE-VIT cluster on the chromosome 18 (bin 18_1, P-value=0.0056, with wts1; full results not shown).

Focusing on bins containing genes associated with autoimmune diseases, no evidence for linkage was detected in bin 1_6 (which contains PTPN22) or bin 2_7 (CTLA4), in either the full analysis of all diseases, or in the focused analysis of only those associated with these genes (Table 2). Similarly, IL23R (bin 1_4) would not have been detected, despite its potential role in IBD, MS, PS, CD and AS. The relative risks conferred by variants in these genes are modest, but differ across diseases (Table 3), and our study might lack power to detect linkage. The power to detect linkage at PTPN22 and CTLA4 in a study of affected sibling pairs with the same number of affected individuals as in the disease-associated clusters is 12 and 3% for PTPN22, with 1 and <0.1% for CTLA4 for genome-wide and suggestive levels of significance, respectively.

Table 3. Genotype relative risks and frequency of PTPN22 and CTLA4 risk variants, showing inferred sibling relative risk accounted for by each locus, the sample size in number of families from the GSMA study in each gene-associated cluster and the power to detect linkage at suggestive and genome-wide levels of significance.

| PTPN22 | HapMap frequencya | Genotypic RR | References | λS | Sample size | Power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1858C>T (rs2476601) | 0.142 | T/C (g1) | T/T (g2) | (suggestive/genomewide) | |||

| T1D | 1.84 | 3.56 | 70 | ||||

| AITDb | 1.66 | 2.14 | 70 | ||||

| RA | 1.66 | 2.89 | 70 | ||||

| SLE | 1.41 | 3.25 | 70 | ||||

| JRA | 1.27 | 1.89 | 70 | ||||

| VIT | 2.35 | 3.42 | 71 | ||||

| PTPN22-associated clusterc | 1.69 | 2.89 | 1.05 | 3573 | 12/3% | ||

| CTLA4 | |||||||

| +6230G>A (CT60) (rs3087243) | 0.542 | A/G (g1) | G/G (g2) | (suggestive/ genome-wide) | |||

| T1D | 1.14 | 1.50 | 9 | ||||

| AITD | 1.59 | 2.32 | 72 | ||||

| CD | 1.31 | 1.44c | 73 | ||||

| SLE | 1.67 | 1.82 | 74 | ||||

| CTLA4-associated clusterd | 1.47 | 1.89 | 1.02 | 2775 | 1/<0.1% | ||

In CEU samples, HapMap frequencies for the associated variants were considered to reduce variability from individual study estimates.

Estimated for Graves disease.

Calculated as g12.

Weighted average for the square root of the total number of affected for each disease.

Discussion

This meta-analysis of all genome-wide linkage screens performed on autoimmune diseases is the first attempt to combine evidence from linkage studies to identify loci which confer susceptibility to autoimmunity independent of disease phenotype. With 42 genome-wide linkage searches included, this forms the largest GSMA study performed to date. We detected highly significant evidence for linkage in the HLA region and flanking bins, confirming that the most potent genetic influence on susceptibility to autoimmunity is the major histocompatibility complex (MHC).

Outside this region, suggestive evidence of linkage was consistently observed only on chromosome 16p. Further, we detected no excess of regions achieving nominally significant evidence for linkage, implying that no loci exist with large sibling relative risk (eg, λS>1.15) acting across a substantial subset of the diseases. Other large GSMA studies, such as BMI and obesity (37 studies)75 and schizophrenia (32 studies; MY Ng, personal communication), showed a similar pattern of results with few strongly linked regions. The failure of our study to detect PTPN22 and CTLA4, and the fact that strong GWA findings in complex diseases are rarely located in regions highlighted in linkage studies, illustrates the different profiles of risk variants that can be identified in association studies and in linkage studies. Most disease alleles identified through association are common and confer modest increased risk to disease; in contrast, large linkage studies, such as this meta-analysis with over 7300 families, lack power to detect these common low-risk genes. There is growing evidence that multiple rare variants and structural variations have a function in the susceptibility of common diseases,76, 77 Some rare variants might be more easily detected in linkage studies, which can have higher power to detect rare, high penetrance variants or where allelic heterogeneity within genes exists.

The chromosome 16 region (16p13.2-p12.3) provided suggestive evidence for linkage across diseases and weighting functions, so may harbour a pleiotropic gene (or genes) conferring risk for several autoimmune diseases. This region has not been highlighted in individual linkage studies or previous meta-analyses of specific diseases, which may reflect the power of the GSMA method to identify novel linked chromosomal regions that were not detected in the contributing studies. Analysis of different bin widths delineated a minimal linkage region of ∼20 cM (18.1–38.5 cM; 10.0–19.8 Mb), which contains several candidate genes potentially involved in autoimmune diseases. In particular, TNFRSF17 (MIM 109545), the tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17, is a receptor preferentially expressed in mature B lymphocytes, and may be important for B-cell development and autoimmune response; CIITA class II (MIM 60005) is an MHC transactivator, encoding a protein located in the nucleus and acting as a positive regulator of class II MHC gene transcription; and the IGSF6 gene (MIM 60622), immunoglobulin superfamily member 6. A recently published genome-wide association study identified the KIAA0350 gene on chromosome 16p13.13 (10.9–11.2 Mb) as a potential locus for T1D.8, 9, 10 Power calculations on the basis of the identified associated variant show that this gene is unlikely to account for the linkage signal (power to detect suggestive linkage was <0.1%), suggesting either the presence of other risk variants not yet identified at KIAA0350, other susceptibility genes in the region, or a coincidental result.

Although the pathogenic mechanisms responsible for the initiation of autoimmunity remain poorly understood, studies clearly demonstrate that genetic predisposition is a major factor in autoimmune diseases susceptibility. It has been hypothesized that certain immunological pathways are common to multiple diseases, whereas other pathophysiological mechanisms are specific to a particular disease. Indeed, familial clustering of autoimmune diseases has been observed, and loci identified for a specific disease often overlap with loci implicated in other autoimmune diseases, suggesting the presence of pleiotropic genes. Many different approaches (including linkage, association and functional studies) will be needed to dissect the genetic contribution to autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the UK MRC to CML (G0400960) and from the US NIH (K24 AR02175) and a Kirkland Scholar Award to LAC. We thank the following investigators who contributed original genome-wide linkage results or provided additional unpublished information: Susan Neuhausen (funded by NIH DK50678), Christopher Amos, Christopher Mathew, David van Heel and Richard Houlston.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Vyse TJ, Todd JA. Genetic analysis of autoimmune disease. Cell. 1996;85:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heward J, Gough SC. Genetic susceptibility to the development of autoimmune disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;93:479–491. doi: 10.1042/cs0930479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torfs CP, King MC, Huey B, Malmgren J, Grumet FC. Genetic interrelationship between insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, the autoimmune thyroid diseases, and rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;38:170–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KG, Simon RM, Bailey-Wilson JE, et al. Clustering of non-major histocompatibility complex susceptibility candidate loci in human autoimmune diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9979–9984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand O, Gough S, Heward J. HLA, CTLA-4 and PTPN22: the shared genetic master-key to autoimmunity. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405009981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA, et al. A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21. Nat Genet. 2007;39:827–829. doi: 10.1038/ng2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WTCCC Genome-wide association study of 14 000 cases of seven common diseases and 3000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD, et al. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:857–864. doi: 10.1038/ng2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakonarson H, Grant SF, Bradfield JP, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature. 2007;448:591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature06010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. 2008;40:204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise LH, Lanchbury JS, Lewis CM. Meta-analysis of genome searches. Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63:263–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1999.6330263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heel DA, Fisher SA, Kirby A, Daly MJ, Rioux JD, Lewis CM. Inflammatory bowel disease susceptibility loci defined by genome scan meta-analysis of 1952 affected relative pairs. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:763–770. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forabosco P, Gorman JD, Cleveland C, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies of systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2006;7:609–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanowski J, Bouzigon E, Forabosco P, Ng MY, Fisher SA, Lewis CM. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies for multiple sclerosis, using an extended GSMA method. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:703–710. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SJ, Rho YH, Ji JD, Song GG, Lee YH. Genome scan meta-analysis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:166–170. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagoo GS, Tazi-Ahnini R, Barker JW, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide studies of psoriasis susceptibility reveals linkage to chromosomes 6p21 and 4q28-q31 in Caucasian and Chinese Hans population. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1401–1405. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babron MC, Nilsson S, Adamovic S, et al. Meta and pooled analysis of European coeliac disease data. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:828–834. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forabosco P, Ng MY, Bouzigon E, Fisher SA, Levinson DF, Lewis CM. Data acquisition for meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies using the genome search meta-analysis method. Hum Hered. 2007;64:74–81. doi: 10.1159/000101425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concannon P, Erlich HA, Julier C, et al. Type 1 diabetes: evidence for susceptibility loci from four genome-wide linkage scans in 1,435 multiplex families. Diabetes. 2005;54:2995–3001. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada MM, Brant SR, Nicolae DL, et al. A genome scan in 260 inflammatory bowel disease-affected relative pairs. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:513–520. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Nicolae DL, Gold LH, et al. Identification of novel susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease on chromosomes 1p, 3q, and 4q: evidence for epistasis between 1p and IBD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7502–7507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampe J, Schreiber S, Shaw SH, et al. A genomewide analysis provides evidence for novel linkages in inflammatory bowel disease in a large European cohort. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:808–816. doi: 10.1086/302294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Ohmen JD, Li Z, et al. A genome-wide search identifies potential new susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:271–278. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavola-Sakki P, Ollikainen V, Helio T, et al. Genome-wide search in Finnish families with inflammatory bowel disease provides evidence for novel susceptibility loci. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:112–120. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, et al. Genomewide search in Canadian families with inflammatory bowel disease reveals two novel susceptibility loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1863–1870. doi: 10.1086/302913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heel DA, Dechairo BM, Dawson G, et al. The IBD6 Crohn's disease locus demonstrates complex interactions with CARD15 and IBD5 disease-associated variants. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2569–2575. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Van Steen K, et al. Genome wide scan in a Flemish inflammatory bowel disease population: support for the IBD4 locus, population heterogeneity, and epistasis. Gut. 2004;53:980–986. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CN, Kocher K, Lander ES, Daly MJ, Rioux JD. Using a genome-wide scan and meta-analysis to identify a novel IBD locus and confirm previously identified IBD loci. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:375–381. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadley S, Sawcer S, D'Alfonso S, et al. A genome screen for multiple sclerosis in Italian families. Genes Immun. 2001;2:205–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coraddu F, Sawcer S, D'Alfonso S, et al. A genome screen for multiple sclerosis in Sardinian multiplex families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:621–626. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyment DA, Sadovnick AD, Willer CJ, et al. An extended genome scan in 442 canadian multiple sclerosis-affected sibships: a report from the canadian collaborative study group. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1005–1015. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraksoy M, Kurtuncu M, Akman-Demir G, et al. A whole genome screen for linkage in Turkish multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;143:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenealy SJ, Babron MC, Bradford Y, et al. A second-generation genomic screen for multiple sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:1070–1078. doi: 10.1086/426459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuokkanen S, Gschwend M, Rioux JD, et al. Genomewide scan of multiple sclerosis in Finnish multiplex families. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1379–1387. doi: 10.1086/301637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawcer S, Ban M, Maranian M, et al. A high-density screen for linkage in multiple sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:454–467. doi: 10.1086/444547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Shirasawa S, Ishikawa N, et al. Identification of susceptibility loci for autoimmune thyroid disease to 5q31-q33 and Hashimoto's thyroiditis to 8q23-q24 by multipoint affected sib-pair linkage analysis in Japanese. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1379–1386. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.13.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JC, Gough SC, Hunt PJ, et al. A genome-wide screen in 1119 relative pairs with autoimmune thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:646–653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer Y, Barbesino G, Greenberg DA, Concepcion E, Davies TF. A new Graves disease-susceptibility locus maps to chromosome 20q11. 2. International Consortium for the Genetics of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1749–1756. doi: 10.1086/302146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asumalahti K, Laitinen T, Lahermo P, et al. Psoriasis susceptibility locus on 18p revealed by genome scan in Finnish families not associated with PSORS1. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:735–740. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karason A, Gudjonsson JE, Jonsson HH, et al. Genetics of psoriasis in Iceland: evidence for linkage of subphenotypes to distinct Loci. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1177–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YA, Ruschendorf F, Windemuth C, et al. Genomewide scan in german families reveals evidence for a novel psoriasis-susceptibility locus on chromosome 19p13. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1020–1024. doi: 10.1086/303075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli-Richard C, Zouali H, Said-Nahal R, et al. Significant linkage to spondyloarthropathy on 9q31–34. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1641–1648. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair RP, Henseler T, Jenisch S, et al. Evidence for two psoriasis susceptibility loci (HLA and 17q) and two novel candidate regions (16q and 20p) by genome-wide scan. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1349–1356. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.8.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson L, Enlund F, Torinsson A, et al. A genome-wide search for genes predisposing to familial psoriasis by using a stratification approach. Hum Genet. 1999;105:523–529. doi: 10.1007/s004399900182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal CD, Clough RL, Barber RC, et al. Identification of a novel psoriasis susceptibility locus at 1p and evidence of epistasis between PSORS1 and candidate loci. J Med Genet. 2001;38:7–13. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos CI, Chen WV, Lee A, et al. High-density SNP analysis of 642 Caucasian families with rheumatoid arthritis identifies two new linkage regions on 11p12 and 2q33. Genes Immun. 2006;7:277–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S, Shephard N, Liu G, et al. Whole-genome scan, in a complex disease, using 11 245 single-nucleotide polymorphisms: comparison with microsatellites. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:54–64. doi: 10.1086/422195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio YFJ, Bukulmez H, Petit-Teixeira E, et al. Dense genome-wide linkage analysis of rheumatoid arthritis, including covariates. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2757–2765. doi: 10.1002/art.20458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa S, Hayashi S, Tsukamoto Y, et al. Identification of the gene loci that predispose to rheumatoid arthritis. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1891–1895. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.12.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner CP, Ding YC, Steele L, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis of 160 north american families with celiac disease. Genes Immun. 2007;8:108–114. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naluai AT, Nilsson S, Gudjonsdottir AH, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis of Scandinavian affected sib-pairs supports presence of susceptibility loci for celiac disease on chromosomes 5 and 11. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:938–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popat S, Bevan S, Braegger CP, et al. Genome screening of coeliac disease. J Med Genet. 2002;39:328–331. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.5.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux JD, Karinen H, Kocher K, et al. Genomewide search and association studies in a Finnish celiac disease population: Identification of a novel locus and replication of the HLA and CTLA4 loci. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130:345–350. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laval SH, Timms A, Edwards S, et al. Whole-genome screening in ankylosing spondylitis: evidence of non-MHC genetic-susceptibility loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:918–926. doi: 10.1086/319509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Luo J, Bruckel J, et al. Genetic studies in familial ankylosing spondylitis susceptibility. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2246–2254. doi: 10.1002/art.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Selby SA, et al. Genome screening in human systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a second Minnesota cohort and combined analyses of 187 sib-pair families. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:547–556. doi: 10.1086/302767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskenmies S, Lahermo P, Julkunen H, Ollikainen V, Kere J, Widen E. Linkage mapping of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in Finnish families multiply affected by SLE. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e2–e5. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.009977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath SK, Quintero-Del-Rio AI, Kilpatrick J, Feo L, Ballesteros M, Harley JB. Linkage at 12q24 with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is established and confirmed in hispanic and european american families. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:73–82. doi: 10.1086/380913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SD, Moroldo MB, Guyer L, et al. A genome-wide scan for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in affected sibpair families provides evidence of linkage. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2920–2930. doi: 10.1002/art.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Huang W, Gui JP, et al. A novel linkage to generalized vitiligo on 4q13-q21 identified in a genomewide linkage analysis of chinese families. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:1057–1065. doi: 10.1086/430279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardi F, Levinson DF, Lewis CM. GSMA: software implementation of the genome search meta-analysis method. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4430–4431. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, White RL, Weber JL. Comprehensive human genetic maps: individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:861–869. doi: 10.1086/302011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos LF, Kamdar BB, Ramsay PP, et al. Clustering of autoimmune diseases in families with a high-risk for multiple sclerosis: a descriptive study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:924–931. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70552-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N. Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits. III. The effect of marker polymorphism on analysis of affected relative pairs. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:242–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E, Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DF, Levinson MD, Segurado R, Lewis CM. Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part I: Methods and power analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:17–33. doi: 10.1086/376548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Murphy K, Raj T, He C, White PS, Matise TC. A combined linkage-physical map of the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:1143–1148. doi: 10.1086/426405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando MM, Stevens CR, Walsh EC, et al. Defining the role of the MHC in autoimmunity: a review and pooled analysis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Rho YH, Choi SJ, et al. The PTPN22 C1858T functional polymorphism and autoimmune diseases—a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:49–56. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge GS, Bennett DC, Fain PR, Spritz RA. PTPN22 is genetically associated with risk of generalized vitiligo, but CTLA4 is not. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1757–1762. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavvoura FK, Akamizu T, Awata T, et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 gene polymorphisms and autoimmune thyroid disease: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3162–3170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belzen MJ, Mulder CJ, Zhernakova A, Pearson PL, Houwen RH, Wijmenga C. CTLA4 +49 A/G and CT60 polymorphisms in Dutch coeliac disease patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:782–785. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres B, Aguilar F, Franco E, et al. Association of the CT60 marker of the CTLA4 gene with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2211–2215. doi: 10.1002/art.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders CL, Chiodini BD, Sham P, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies in BMI and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2263–2275. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlov IP, Gorlova OY, Sunyaev SR, Spitz MR, Amos CI. Shifting paradigm of association studies: value of rare single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:100–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T, McClellan JM, McCarthy SE, et al. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.