Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD), a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons and their terminations in the basal ganglia, is thought to be related to genetic and environmental factors. Although the pathophysiology of PD neurodegeneration remains unclear, protein misfolding, mitochondrial abnormalities, glutamate dysfunction and/or oxidative stress have been implicated. In this study, we report that a rare T1492G variant in GLUD2, an X-linked gene encoding a glutamate dehydrogenase (a mitochondrial enzyme central to glutamate metabolism) that is expressed in brain (hGDH2), interacted significantly with age at PD onset in Caucasian populations. Individuals hemizygous for this GLUD2 coding change that results in substitution of Ala for Ser445 in the regulatory domain of hGDH2 developed PD 6–13 years earlier than did subjects with other genotypes in two independent Greek PD groups and one North American PD cohort. However, this effect was not present in female PD patients who were heterozygous for the DNA change. The variant enzyme, obtained by substitution of Ala for Ser445, showed an enhanced basal activity that was resistant to GTP inhibition but markedly sensitive to modification by estrogens. Thus, a gain-of-function rare polymorphism in hGDH2 hastens the onset of PD in hemizygous subjects, probably by damaging nigral cells through enhanced glutamate oxidative dehydrogenation. The lack of effect in female heterozygous PD patients could be related to a modification of the overactive variant enzyme by estrogens.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease onset, glutamate dehydrogenase, gain-of-function, estrogens

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) affects about 1.8% of people over the age of 65 years.1 It is clinically characterized by tremor, rigidity and bradykinesia, which often occur along with disturbances of posture and gait.2 About 80% of PD cases are sporadic, with males being more frequently affected than females (ratio=1.5:1).

The etiology of PD remains largely unknown, although interplay of environmental toxins with genetic susceptibility may be operational. The genetic hypothesis is supported by community-based studies showing that a substantial number of PD patients have similarly affected relatives.3, 4 This was also revealed by a PD study conducted by us on Crete,5 an island of about 0.6 million people sharing the same genetic and cultural background and a common environment. Moreover, this study suggested an oligogenic model for PD, according to which disease-predisposing alleles from two or more genes need to be present in the same individual for the disorder to be expressed.

With regard to the pathophysiology of PD, several hypotheses have been proposed in an attempt to explain the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in this disorder. One of these suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction is involved,6 a contention supported by the recent discovery of monogenetic forms of PD resulting from mutations of mitochondrial proteins or mitochondria-interacting proteins.7 These mutations, however, are generally not found in the common, mostly sporadic, form of the disease.

Another theory holds that excessive glutamate action on postsynaptic excitatory receptors6 is to blame, but, to this day, the etiological role of glutamate excitotoxicity in human degenerations remains elusive. Abnormalities in glutamate metabolism have been reported in patients with neurodegenerative disorders,8 including PD,9 raising the possibility that metabolic defects involving this amino acid might be operational. Some of these patients had altered activities and increased thermal stability of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH),10 a mitochondrial enzyme expressed in midbrain dopaminergic neurons11 that catalyzes glutamate oxidation.

Whereas no sequence variation has been detected in the GLUD1 gene that encodes the housekeeping mammalian GDH (hGDH1 in the human) in the above disorders, recent studies revealed that humans and apes have additionally acquired an X-linked GLUD2 gene encoding a highly homologous heat-labile isoform of GDH. This novel hGDH2 shows distinct regulatory properties and expression pattern being mainly found in retina, brain and testis.12, 13 In light of these findings, we searched for disease-predisposing alleles in PD by studying the GLUD2 gene in PD patients from two different populations of a diverse genetic background. Results revealed that hemizygous individuals for the Ser445Ala rare polymorphism developed PD 6–13 years earlier than did PD patients with other genotypes. The Ala445-hGDH2 mutant, obtained in recombinant form, showed an increased basal catalytic function and sensitivity to inhibition by estrogens. Results are detailed below.

Patients and methods

Patients

The Greek PD sample consisted of two independent cohorts. The first was from Crete and was recruited through the Neurology Services of the University Hospital of Heraklion,5 whereas the second was from Central Greece and was recruited from the Movement Disorder Clinics of the University Hospitals of Larissa (Thessaly)14 and Patras (Northern Peloponnese).15 The North American PD cohort was from Central California and was recruited through a population-based study16 of the UCLA School of Public Health. When PD was encountered in more than one family member, only the index case was included, as members of the same kindred may share genetic polymorphisms. Written consent was obtained from all participants according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards. Details on the diagnostic criteria17 followed for the recruitment of PD patients in all cohorts participating in this study are provided as Supplementary Information.

Controls

Healthy controls were randomly selected from the local population of Crete (N=521); their age and gender distribution matched those of the PD patient's group. Controls from Central California (N=100) were subjects without PD before or during this study, with an age and gender distribution being comparable with those of the American PD cohort. Both groups of controls underwent a structured interview and were assessed for the presence of cognitive deficits using the mini mental state examination test (MMSE).18 Individuals who had MMSE scores below 25 were excluded. Written consent was obtained from all participants according to the protocols approved by the institutional review board.

DNA sample handling

DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using standard procedures. All samples from the University of Crete were assigned a unique code number, and genotypic analysis was carried out blindly for the individual phenotypes. With regard to the DNA analysis of the PD samples from the collaborating institutions, a predesigned protocol was used for sharing DNA samples and clinical information. According to this, an ID number was assigned to each DNA sample and no additional information was provided to the University of Crete, where the DNA genotypic analyses were performed. After each collaborating center received genotypic data of the samples, details regarding demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were made known to the University of Crete.

Mutation screening and genotypic analysis

Oligonucleotide primers were designed specifically to amplify the intronless GLUD2 gene (NM_012084), including its putative promoter. Primer sequences and PCR amplification conditions are available on request. Mutation analysis of amplimers was performed using the ABI BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit on an ABI Prism 3100-direct automated genetic analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems Inc, Foster City, CA, USA). Chromatograms from PD patients were subsequently analyzed using the software Sequencher v4.0.5 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) to determine the presence of any (known or novel) variation within this gene.

After the identification of the G103A polymorphism, which causes the substitution of Arg for Gly35, we used the SnapShot assay (Applied Biosystems Inc) performed on an Applied Biosystems Prism 3100 Genetic Analyser platform to genotype PD subjects and controls from Crete. Primer sequences for PCR amplification and extension primers for SNaPshot assay are available on request. After the detection of the T1492G change in the coding region of the GLUD2 gene, leading to Ser445Ala substitution, RFLP analysis was used to genotype all PD patients and controls participating in this study. The T1492G variant created a restriction site for the enzyme AciI (New England Biolabs, Inc, Beverly, MA, USA), and the resulting 204 and 323 bp subfragments were visualized on a 3% agarose gel. Putative carriers of the T1492G variant were sequenced to confirm their genotype.

All genotypic analyses were performed blindly using a predesigned protocol (see DNA sample handling).

Production, expression and purification of the variant and wild-type GDHs

Using genomic DNA from a male PD patient carrying the T1492G variant as a template, a 527 bp segment of the GLUD2 gene was PCR amplified (primers: 5′-TGAATGCTGGAGGAGTGACA-3′ and 5′-TGGATTGACTTGAGAATGG-3′). From this amplified segment, a 350 bp fragment containing the T1492G change was cleaved using BsmI and BsrGI restriction endonucleases (New England Biolabs) and inserted into a BsmI/BsrGI-digested GLUD2 cDNA cloned in pBSKII+ vector, replacing the corresponding region of the gene. Cloning of human GLUD2 and GLUD1 genes in pBSKII+ vector has been described elsewhere.12

The variant 1492G-GLUD2 cDNA, along with the wild-type GLUD1 and GLUD2 cDNAs, was subcloned into pVL1393 and pVL1392 vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively, and expressed in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf21) cells using the baculovirus expression system as previously described.19 The virus was amplified by three rounds of infection. Cultured cells expressing the recombinant GDH proteins were harvested 5 days after infection. The produced recombinant hGDHs were purified from Sf21 cell extracts using a previously described method19 that involves ammonium sulfate fractionation, hydrophobic interaction and hydroxyapatite chromatography. Purified hGDHs were used for enzyme assays and for studying their electrophoretic mobility by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentration of samples was determined densitometrically on stained SDS-PAGE gels, using bovine serum albumin as a standard. All hGDH proteins studied were produced and analyzed in parallel.

Functional analyses of recombinant GDH proteins

Glutamate dehydrogenase activity was assayed spectrophotometrically (at 340 nm and 25°C) in the direction of reductive amination of α-ketoglutarate. The standard reaction mixture of 1 ml contained 50 m triethanolamine pH 8.0 buffer, 2.6 m EDTA, 100 m ammonium acetate, 100 μ NADPH and about 1 μg of purified enzyme, unless otherwise indicated. Enzyme reaction was initiated by adding α-ketoglutarate to 8 m. Initial rates (enzyme velocity at the interval during which the change in absorbance maintained linearity) were recorded. Kinetic analyses were performed to determine the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) for α-ketoglutarate, ammonia and glutamate. Regulation of the human recombinant GDHs was studied by adding positive modulator ADP/-leucine to the reaction mixture.19 The effect of diethylstilbestrol (DES) and GTP on the basal catalytic activity of the Ser445Ala variant and the wild-type human GDHs was assayed by adding these allosteric regulators to the reaction mixture, in the absence of ADP, at various concentrations (DES: 0–50 μ, GTP: 0–1000 μ). For heat inactivation studies, samples containing about 50 μg/ml of purified enzyme were incubated at 47.5°C, and aliquots were removed at specified time intervals and assayed immediately for enzyme activity. Details on enzyme assays, kinetic analyses, allosteric regulation and heat inactivation studies are provided elsewhere.19

Statistical analyses

A t-test and χ2-test were performed to assess differences in age and gender distribution, respectively, between patients and controls, with a significance level of P=0.05. Pearson's χ2 and Fisher's exact tests (v. 15.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were used to evaluate differences in allele frequencies between cases and unaffected individuals. Independent samples t-test was used to examine the effect of GLUD-2 Ser445Ala genotypes on age at PD onset. The analysis was performed in the combined, as well as in the stratified by gender, group of patients. Analysis and plotting of enzymatic data were carried out using the Microcal Origin program (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Kinetic constants were calculated by least-square fitting to the hyperbolic Michaelis–Menten function. IC50 and SC50 values were determined from the activation and inhibition curves of the corresponding allosteric regulators. The Hill plot coefficients for GTP inhibition were calculated according to the method described by Cornish-Bowden.20

Results

We studied 808 PD patients: 584 from Greece and 224 from Central California. The Greek group encompassed 281 PD patients from Crete and 303 PD patients from Central Greece. As shown in Table 1, the demographic and clinical data of the combined Greek PD sample and of the American PD cohort were comparable. However, familial PD was more frequently encountered in the Greek than in the American PD sample (Table 1). Moreover, although the ‘mixed-type' PD was more prevalent among Greek patients, the ‘akinetic-rigid' type occurred more often in the American group (Table 1). In this regard, the PD type was ascertained 6–7 years after onset in the Greek group and 1–3 years after diagnosis in the American cohort. As such, these data are consistent with the natural history of PD, which often becomes more of a mixed type over time.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of Parkinson's disease patients in the two independent cohorts.

| Greece | Central California | |

|---|---|---|

| Total (N) | 584 | 224 |

| Males (%) | 335 (57.4) | 119 (53.1) |

| Females (%) | 249 (42.6) | 105 (46.9) |

| Sporadic (%) | 420 (72) | 198 (88.4) |

| Familial (%) | 164 (28)* | 26 (11.6) |

| Age at onset (years; mean±SD) | 63.48±10.8 | 68.0±11.0a |

| PD type | ||

| Tremorogenic (%) | 132 (22.6) | 83 (37.0) |

| Mixed (%) | 284 (48.6) | 25 (11.2) |

| Akinetic-rigid (%) | 168 (28.8) | 116 (51.8) |

*P<0.001 (OR=2.27, 95% CI=1.86–4.77) as compared with the occurrence of familial cases in the American group.

Age at diagnosis (years; mean±SD) refers to the age at which the patient was first diagnosed with PD by his/her physician. For the Greek sample, the mean age (±SD) at disease onset refers to the age at which the patient first experienced symptoms of PD. Age differences at disease diagnosis between the two cohorts were not significant (P=0.719). In the Greek PD group, the type of PD (tremorogenic, mixed or akinetic-rigid) was ascertained 6–7 years after disease onset, whereas in the North American cohort 1–3 years after first diagnosis. It is known that as the disease progresses PD tends to become more of a mixed type over time.

Sequencing of the entire GLUD2 gene, including its promoter region, in 199 PD patients from Crete led to the identification of two single-nucleotide polymorphisms within the coding region. The first, a common nonsynonymous change (G103A) resulting in the substitution of Arg for Gly35 in the leader peptide, was present in 16.7% of PD chromosomes (n=287) and in 18.3% of control chromosomes (n=104; P=0.836). This G103A polymorphism did not interact significantly with the phenotypic features of PD patients, including age at disease onset (data not shown). The second was a nonsynonymous change (T1492G) resulting in the substitution of Ala for Ser445 in the regulatory domain of hGDH2 (Supplementary Figure 1).

Studies on PD subjects from Crete (N=281) revealed that male patients harboring the G allele developed PD at 50.0±6.98 years, whereas patients with other T1492G genotypes experienced disease onset at 64.62±10.2 years (mean±SD; P<0.01). Furthermore, a study of an independent group of PD patients from Central Greece replicated these results by showing that G hemizygotes developed PD at a younger age than did PD patients with other genotypes. In the combined Greek PD cohort (N=584), male PD patients with the G allele experienced onset of PD symptoms 13.1 years earlier than G/T heterozygous females (P<0.001, Table 2). Moreover, male patients with the G allele developed PD 9.4 years earlier than male PD patients with the T allele (P=0.003) and 8.3 years earlier than female PD patients with the T/T genotype (P=0.01). Analysis of the North American PD sample (N=224) also revealed that G hemizygotes developed PD 13.1 years earlier than G/T heterozygotes (P<0.05). However, although American male PD patients with the G allele developed PD 6.1 and 7.4 years earlier than PD patients with the T and T/T genotypes, respectively, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2). As such, the mean age difference was greater (13.1 years) when G hemizygous individuals were compared with G/T heterozygous individuals, both in the combined Greek group and in the American cohort. Stratification of data from the Greek and American PD groups revealed that gender did not affect age at development of PD. Furthermore, clinical type of PD (akinetic, tremorogenic or mixed) showed no significant interaction with the Ser445Ala polymorphism (Table 1).

Table 2. Interaction of T1492G polymorphism with age at onset of Parkinson's disease.

| Genotypes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (total N=335) | Females (total N=249) | |||

| (a) Greek PD patientsa | G | T | G/T | T/T |

| Number of patients (total=584) | 12 | 323 | 18 | 231 |

| Age at onset (years) (mean±SD) | 54.6±11.1 | 64.0±10.7 | 67.7±8.1 | 62.9±11.0 |

| P=0.003 | P<0.001 | P=0.01 | ||

| Genotypes | ||||

| Males (N=119) | Females (N=105) | |||

| (b) North American PD patients | G | T | G/T | T/T |

| Number of patients (total=224) | 6 | 113 | 8 | 97 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) (mean±SD) | 61.3±15.7 | 67.4±10.7 | 74.4±5.8 | 68.7±11.3 |

| P<0.05 | ||||

North American PD patients: P-value refers to comparison between G hemizygotes and G/T heterozygotes.

Greek PD patients: The first and the replication Greek study combined; P-values refer to comparisons between PD patients with the particular genotype (T, G/T or TT) and G hemizygotes.

The frequency of the T1492G polymorphism was rare in all populations studied, with the G allele being present in 3.6% of the combined Greek PD cohort (N=584) and in 4.3% of the American PD group (N=224) (Supplementary Table 1). No significant differences were found in the distribution of this GLUD2 variant among PD patients and controls. Moreover, the frequency of the detected polymorphism (T1492G) was comparable among patients with familial PD and sporadic PD. Among the G hemizygous familial PD cases, we identified a 52-year-old man affected by PD at the age of 40 years, who had inherited the 1492G allele from his unaffected mother. His father (harboring the 1492T allele) had developed typical, L-dopa responsive PD at the age of 62 years and died of his illness at the age of 75 years (Supplementary Figure 2).

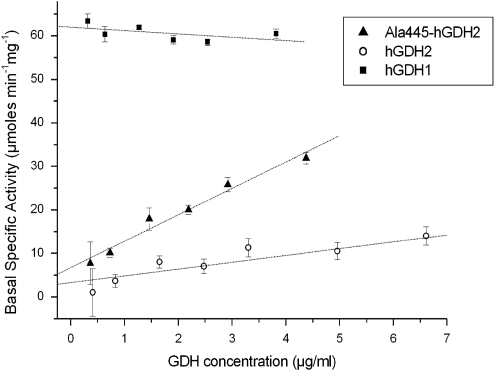

Expression of mutant Ser445Ala GLUD2, as well as of the wild-type GLUD2 and GLUD1 genes in Sf21 cells, produced catalytically active enzymes. A functional analysis of the recombinant proteins, purified to homogeneity (Supplementary Figure 3), revealed that the Ala445-hGDH2 variant showed a basal-specific activity that was substantially greater than that of the wild-type hGDH2 (Figure 1). At enzyme concentrations of about 5 μg/ml, the basal-specific activity of the Ala445-hGDH2 variant approached that of wild-type hGDH1 (Figure 1). However, in contrast to wild-type hGDH1, the basal activity of the Ala445-hGDH2 variant was resistant to suppression by GTP (Table 3). Moreover, unexpectedly, the Ser445Ala hGDH2 variant was markedly sensitive to inhibition by estrogens (IC50±SE=19±5 nmol/l DES) compared with the wild-type housekeeping hGDH1 (IC50±SE=1530±46 nmol/l DES; P<0.001) (Table 3, Supplementary Figure 4). This sensitivity to estrogens was also evident when the variant enzyme was activated by 0.1 m ADP or 1.0 m ADP (Supplementary Figures 5 and 6). In addition, the Ser445Ala change increased the thermal stability of the variant as compared with the wild-type hGDH2 (Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 1.

Basal-specific activities of purified recombinant Ala445-hGDH2, hGDH2 and hGDH1. Assays were performed at 25°C in the absence of allosteric effectors. Each point represents the mean±SEM (bar) of three to five experimental determinations. The slope (±SE) of each regression line is given below as the rate of change of specific activity (in μmol/min/mg) per μg increase in enzyme concentration. The R correlation coefficient and the P-value (probability that R is zero) of the linear regression are given in parentheses. Slope for Ala445-hGDH2: 6.06±0.52 (R=0.986, P=0.0003). Slope for hGDH2: 1.56±0.23 (R=0.940, P=0.0005). Slope for hGDH1: −0.76±0.57 (R=−0.556, P=0.251).

Table 3. Modification of the basal catalytic activity of the Ser445Ala variant and the wild-type human GDHs by diethylstilbestrol (DES), GTP, ADP and -leucine.

| hGDH1 | Ala445-hGDH2 | hGDH2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DES inhibition | |||

| IC50 (μm/l) | 1.53±0.05 | 0.02±0.01 (21)* | 0.09±0.01 |

| Hill coefficient | 1.89±0.01 | 0.40±0.02* | 0.52±0.02 |

| GTP Inhibition | |||

| IC50 (μmol/l) | 0.31±0.03 | 29.06±4.48 (27)* | 40.07±4.46 |

| Hill coefficient | 1.51±0.07 | 0.80±0.05* | 0.72±0.05 |

| ADP Activation | |||

| SC50 (μmol/l) | 22.40±2.10 | 58.20±5.50 (24)* | 68.50±2.30 |

| -leucine activation | |||

| SC50 (mmol/l) | 0.86±0.14 | 0.96±0.05 (24) | 1.02±0.21 |

*P<0.001 as compared with wild-type hGDH1. Number in parentheses represents number of experimental determinations. Purified enzyme preparations were used and assays were performed in 50 m TRA buffer (pH 8.0) in the absence or in the presence of various concentrations of the allosteric regulators. The IC50 values and the Hill coefficients (±SE of the fitted parameters) were calculated from the inhibition curves of the modulators according to the method described by Cornish-Bowden.20 The SC50 values were (±SE of the fitted parameters) derived from the activation curves of the enzymes.

Discussion

In this study, we report that a rare variant (T1492G) in GLUD2, an X-linked gene encoding hGDH2, an isoform expressed in the brain, interacted significantly with age at PD onset in two populations of diverse genetic background. Thus, genotypic analyses of 584 Greek patients showed that 1492G hemizygotes developed PD 8–13 years earlier than did patients harboring the T (P=0.003), the G/T (P<0.001) or the T/T (P=0.01) genotype. In the North American cohort (N=224), 1492G hemizygotes also developed PD earlier than did subjects with other genotypes, but mean age differences reached statistical significance only when G hemizygotes were compared with G/T heterozygotes (mean age difference: 13.1 years, P<0.05). As such, although the present association data are compelling for the Greek sample, they are somewhat weaker for the American cohort. This could be because of the fact that the American sample was smaller, given that the detected polymorphism (T1492G) occurs rather rarely in the populations studied (about 4.0% in both the Greek and American samples). It is unclear whether the weaker effect of the T1492G polymorphism in the American PD group relates to the different methods used for ascertaining the patient's age at PD development in the two cohorts or to their distinct genetic background. Whereas in the Greek sample, age at disease onset was considered to be the age at which the patient first experienced symptoms of PD, in the American cohort, this was the age at which the patient was diagnosed with PD by his/her physician. Our data, showing that the mean age at disease onset in the Greek group was 63.5 years and the mean age at PD diagnosis in the American group was 68 years, are consistent with those from previous community-based studies.21, 22 Although the T1492G polymorphism showed a weaker effect in the American PD sample, the observed mean age differences between males with the 1492G allele and subjects with other genotypes were similar in both PD cohorts (6–13 years). Hence, the detected trend toward an effect of the GLUD2 polymorphism in the smaller American cohort supports the thesis that the T1492G variant interacts with age at PD onset. The observed differences cannot be attributed to gender, as an analysis of the entire PD sample revealed no interaction between gender and age at PD development. The same was true when T hemizygotes were compared with females homozygous or heterozygous for the 1492T allele.

As our study evaluated three PD cohorts recruited independently and analyzed blindly, it is highly unlikely that the detected associations relate to ascertainment and other biases. In the populations studied, the frequencies of all four T1492G genotypes were similarly distributed among PD patients and controls. Hence, these data, showing neither a positive nor a negative association of the G allele with PD, are consistent with the random occurrence of this DNA variant in the PD populations studied.

These genotypic data, revealing that the nonsynonymous T1492G GLUD2 change hastens the commencement of PD (probably in susceptible individuals), suggest that the presence of Ala445-hGDH2 accelerates PD neurodegeneration. The variant enzyme, obtained by substitution of Ala for Ser445, showed increased basal activity and thermal stability, thus suggesting that it has acquired gain-of-function properties. How can these findings reconcile with the known functions of GDH and the prevailing models of PD pathogenesis?

Mammalian GDH, a mitochondrial enzyme showing a wide tissue distribution (housekeeping), is known to be allosterically regulated by chemically heterogeneous compounds.23 Of the known endogenous negative modulators, GTP is important for controlling the flux of glutamate through the GDH pathway, as underscored by the finding that regulatory dominant mutations (that attenuate GTP inhibition) of the GLUD1 gene lead to clinical syndromes as a result of enzyme overactivity (gain-of-function effect).24 Estrogen hormones are also known to act as negative endogenous modulators of mammalian housekeeping GDH (hGDH1 in human), but these effects require micromolar concentrations,25 which are not likely to occur in vivo. However, the wild-type hGDH2, although highly homologous to wild-type hGDH1, is regulated by distinct mechanisms.19 This study unexpectedly revealed that these mechanisms rendered the wild-type hGDH2 and the Ala445-hGDH2 variant sensitive to inhibition by estrogens.

There is evidence26 that GLUD1 was retroposed <23 million years ago to the X chromosome, in which it gave rise to GLUD2 through random mutations and natural selection. These mutations provided the novel enzyme with unique properties that are thought to facilitate its function in the particular milieu of the nervous system. hGDH2, having been dissociated from GTP control (through the Gly456Ala change),27 is mainly regulated by rising levels of ADP/-leucine. Resistance of hGDH2 to GTP may enable the brain enzyme to metabolize neurotransmitter glutamate, even when GTP accumulates as a result of high TCA cycle activity28 in glutamatergic synapses. Conversely, to achieve full-range regulation by these activators, hGDH2 needs to set its basal activity at low levels (about 4–8% of full capacity), a property largely conferred by the evolutionary Arg443Ser change.29 Hence, the detected Ser445Ala change has altered a property that is crucial for the tight regulation of hGDH2.13

Substitution of Ala for Ser445 is predicted by secondary structure prediction programs30 to stabilize the small á-helix of the antenna. A similar stabilizing effect has also been suggested for the Ser445Leu change in hGDH1.31 Both alanine and leucine are considered to be better á-helix formers than serine.32 Stabilization of the α-helix would favor an open mouth conformation, thereby counteracting the capacity of the evolutionary Arg443Ser change of hGDH2 to minimize basal activity. As such, the Ser445Ala change may confer a gain-of-function property to hGDH2.

The mechanism by which the presence of the unduly active hGDH2 variant modifies onset of PD remains unclear, as the normal function of the enzyme is not well understood. The metabolic consequences, however, could be analogous to those observed in HI/HA syndrome, in which enhanced glutamate oxidation (by the overactive hGDH1 mutants) increases ATP production and reduces the glutamate pool involved in urea synthesis.33 In brain, glutamate is distributed in multiple pools,34 the maintenance of which requires the operation of transport systems and metabolizing enzymes, including GDH. Whereas glutamate oxidation in brain proceeds mainly through transamination,35 the GDH-catalyzed reaction assumes importance under conditions of intense excitatory transmission. Under pathological conditions (eg, rotenone toxicity model for PD), glutamate-oxidizing brain mitochondria generate increased amounts of ROS.36 Hence, it is likely that augmentation of glutamate oxidation by Ala445-hGDH2 could accelerate an ongoing degenerative process in PD by altering the compartmented metabolism of glutamate in brain and/or by increasing ROS production.

Although it is difficult for this gain-of-function hypothesis to explain the present data that G/T heterozygotes were not affected by PD at a younger age and that G hemizygotes were, our observations on enzyme modulation unexpectedly showed that estrogen hormones inhibited the enhanced basal activity of the X-linked Ser445Ala variant much more powerfully than that of the widely expressed hGDH1, as noted above. Hence, it seems likely that, in females, estrogens may nullify the gain-of-function effects observed in male patients by blocking the overactive variant enzyme from metabolizing increased amounts of glutamate (and, in the process, damaging nigral cells). Understanding the mechanisms by which the Ser445Ala-hGDH2 variant hastens the commencement of PD symptoms could provide a means for retarding the development of this disorder.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Association for Research and Treatment of Neurologic Disorders of Crete (EY-ZHN) and by the Second Operational Programme for Education and Initial Vocational Training (EPEAEK II) to HL and CS from the Ministry of Education of Greece. We are grateful to PD patients and their families for participating in this study. We also thank Mrs M Rogdaki for her help in genetic studies.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- de Rijk MC, Launer LJ, Berger K, et al. Prevalence of Parkinson's disease in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology. 2000;54:S21–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–424. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz A, Grigoletto F, Baldereschi M, et al. Familial aggregation of Parkinson's disease: a population-based case-control study in Europe. EUROPARKINSON Study Group. Neurology. 1999;52:1876–1882. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood NW. Genetic risk factors in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:S58–S62. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanaki C, Plaitakis A. Bilineal transmission of Parkinson disease on Crete suggests a complex inheritance. Neurology. 2004;62:815–817. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113720.71387.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlante A, Calissano P, Bobba A, et al. Glutamate neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaitakis A, Berl S, Yahr MD. Abnormal glutamate metabolism in an adult-onset degenerative neurological disorder. Science. 1982;216:193–196. doi: 10.1126/science.6121377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y, Ikeda K, Shiojima T, Kinoshita M. Increased plasma concentrations of aspartate, glutamate and glycine in Parkinson disease. Neurosci Lett. 1992;145:175–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaitakis A, Berl S, Yahr MD. Neurological disorders associated with deficiency of glutamate dehydrogenase. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:144–153. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaitakis A, Shashidharan P. Glutamate transport and metabolism in dopaminergic neurons of substantia nigra: implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2000;247:II/25–II/35. doi: 10.1007/pl00007757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashidharan P, Michaelidis TM, Robakis NK, et al. Novel human glutamate dehydrogenase expressed in neural and testicular tissues and encoded by an X-linked intronless gene. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16971–16976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaitakis A, Metaxari M, Shashidharan P. Nerve tissue-specific (GLUD2) and housekeeping (GLUD1) human glutamate dehydrogenases are regulated by distinct allosteric mechanisms: implications for biologic function. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1862–1869. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiromerisiou G, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Gourbali V, et al. Screening for SNCA and LRRK2 mutations in Greek sporadic and autosomal dominant Parkinson's disease: identification of two novel LRRK2 variants. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papapetropoulos S, Ellul J, Paschalis C, et al. Clinical characteristics of the alpha-synuclein mutation (G209A)-associated Parkinson's disease in comparison with other forms of familial Parkinson's disease in Greece. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:281–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang GA, Bronstein JM, Masterman DL, et al. Clinical characteristics in early Parkinson's disease in a Central California Population-Based Study. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1133–1142. doi: 10.1002/mds.20513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanavouras K, Mastorodemos V, Borompokas N, Spanaki C, Plaitakis A. Properties and molecular evolution of GLUD2 (neural and testicular tissue-specific) glutamate dehydrogenase. J Neurosc Res. 2007;85:1101–1109. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish-Bowden A. Fundamentals of enzyme kinetics. London: Butterworth; 1979. pp. 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kuopio AM, Marttila RJ, Helenius H, Rinne UK. Changing epidemiology of Parkinson's disease in Southwestern Finland. Neurology. 1999;52:302–308. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM, Bernstein AL, et al. Incidence of Parkinson's disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:1015–1022. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RC, Daniel RM. L-glutamate dehydrogenases: distribution, properties and mechanism. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1993;106:767–792. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(93)90031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley CA, Lieu YK, Hsu BY, et al. Hyperinsulinism and hyperammonemia in infants with regulatory mutations of the glutamate dehydrogenase gene. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1352–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JC, Carr DO, Grisolia S. Effect of cofactors, estrogens and magnesium ions on the activity and stability of human glutamate dehydrogenase. Biochem J. 1964;93:409–419. doi: 10.1042/bj0930409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki F, Kaessmann H. Birth and adaptive evolution of a hominoid gene that supports high neurotransmitter flux. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1061–1063. doi: 10.1038/ng1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaganas I, Plaitakis A. Single aminoacid substitution (G456A) in the vicinity of the GTP binding domain of human housekeeping glutamate dehydrogenase markedly attenuates GTP inhibition and abolishes the cooperative behaviour of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26422–26428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaitakis A, Spanaki C, Mastorodemos V, Zaganas I. Study of structure-function relationships in human glutamate dehydrogenases reveals novel molecular mechanisms for the regulation of the nerve tissue-specific (GLUD2) isoenzyme. Neurochem Int. 2003;43:401–410. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaganas I, Spanaki C, Karpusas M, Plaitakis A. Substitution of Ser for Arg443 in the regulatory domain of human housekeeping (GLUD1) glutamate dehydrogenase virtually abolishes basal activity and markedly alters the activation of the enzyme by ADP and L-leucine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46552–46558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B, Yachdav G, Liu J.The predict protein server Nucleic Ac Res 200432(web server issue):W321–W326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Schmidt T, Fang J, et al. The Structure of apo human glutamate dehydrogenase details subunit communication and allostery. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:765–777. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branden C, Tooze J.Motifs of Protein Structurein Garland Publishing 2nd edition: Introduction to protein structure. New York; 199913–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley CA. Hyperinsulinism/hyperammonemias syndrome: insights into the regulatory role of glutamate dehydrogenase in ammonia metabolism. Mol Gen Metab. 2004;81:S45–S51. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikhin Y, Yudkoff M. Compartmentation of brain glutamate metabolism in neurons and glia. J Nutr. 2000;130:1026S–1031S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1026S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna MC. The glutamate-glutamine cycle is not stoichiometric: fates of glutamate in brain. J Neurosc Res. 2007;85:3347–3358. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panov A, Dikalov S, Shalbuyeva N, et al. Rotenone model for Parkinson disease. Multiple brain mitochondrial dysfunction after short term systemic rotenone intoxication. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42026–42035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.