Abstract

The linkage of disease gene mapping with DNA sequencing is an essential strategy for defining the genetic basis of a disease. New massively parallel sequencing procedures will greatly facilitate this process, although enrichment for the target region before sequencing remains necessary. For this step, various DNA capture approaches have been described that rely on sequence-defined probe sets. To avoid making assumptions on the sequences present in the targeted region, we accessed specific cytogenetic regions in preparation for next-generation sequencing. We directly microdissected the target region in metaphase chromosomes, amplified it by degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR, and obtained sufficient material of high quality for high-throughput sequencing. Sequence reads could be obtained from as few as six chromosomal fragments. The power of cytogenetic enrichment followed by next-generation sequencing is that it does not depend on earlier knowledge of sequences in the region being studied. Accordingly, this method is uniquely suited for situations in which the sequence of a reference region of the genome is not available, including population-specific or tumor rearrangements, as well as previously unsequenced genomic regions such as centromeres.

Keywords: genomic selection, enrichment, microdissection, next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Despite recent advances in sequencing technologies, present capabilities do not permit routine whole-genome sequencing for mutation detection. In response, enrichment methods have been described to capture specific sequences from genomes that will work well for most screening studies.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

However, these capture-based enrichment methods are limited in some situations; they require an earlier knowledge of the target sequences for array or primer design and are thus restricted to resequencing projects. They will not be suitable when rare sequence rearrangements are in place; for example, inter-individual differences of highly dynamic structures, such as telomere and subtelomere regions, that might be difficult to capture by the mentioned methods but have relevance to ageing, cancer and inherited disease.8, 9, 10, 11 Other regions, such as pericentromeric heterochromatin, were not targeted by the Human Genome Project because they are difficult to clone and to annotate owing to high repeat content and homology.12 However, heterochromatin comprises 20% of the human genome, and seems to have relevance for gene expression and disease.13, 14, 15 In some linkage or association studies, significant results identify regions that contain no known genes.16, 17 Furthermore, even regions with known genes could feature unrecognized rearrangements or insertion of mobile elements with effects on gene regulation and expression.18, 19, 20 Other frequent examples are cryptic rearrangements in promoter regions or fusion genes in cancer development.21, 22 Those dynamics would be missed or difficult to analyze by the above-mentioned capture methods. Genome-wide paired-end sequencing is extremely sensitive,23 but may not be meaningful or practicable for large-scale screening studies when there already is a localized region of interest. However, next-generation sequencing technologies are developing extremely fast and will probably enable whole-genome sequencing at affordable costs in the near future.

To avoid making a priori assumptions on the sequences in the target region, we developed an approach that could directly start with a patient's chromosomal region linked to a disease. The most direct way is to dissect that suspicious piece of chromosome and sequence it. We have done that by coupling conventional cytogenetics (karyotyping), microdissection and high-throughput sequencing (Figure 1). We present data from three experiments, in which we obtained sequences from as few as six chromosomes and present a proof-of-feasibility protocol.

Figure 1.

Microdissection-based enrichment for next-generation sequencing. The figure shows metaphase chromosomes prepared from lymphoblastoid cells and microdissection of chromosomal region 12p. In this experiment, we microdissected and processed 10 short arms of chromosome 12. The microdissected fragments were amplified by DOP-PCR, followed by the processing protocol for 454 sequencing.

Methods

Preparation of metaphase chromosomes, microdissection and degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR

We prepared metaphase chromosomes from lymphoblastoid cells (chromosome 12p) and from peripheral blood (chromosome 1). Microdissection was performed as described.24 For amplification, we used an adapted degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR (DOP-PCR).24, 25 A detailed protocol for microdissection and DOP-PCR is provided in the supplementary material. Before preparing the 454 library, we verified the specificity of the microdissected material by dye-labeling an aliquot of DOP-PCR product and subsequent hybridization on metaphase chromosomes (reverse painting, reverse fluorescence in situ hybridization, FISH).26

Library preparation

The 454 library was prepared according to the manufacturer's instruction, and included adapter ligation, library immobilization, melting and quantification. We performed an additional reamplification of the 454 library to get a measurable amount of library material. For this purpose, we used the normal Roche 454 amplification primer (20 μ final concentration; Roche, Branford, CT, USA) and performed a standard PCR with 35 cycles (50 μl volume). On the basis of the short length of DOP-PCR products (<200 bp) in the starting material for library preparation, we have not used paired-end sequencing.

Sequencing runs carried out with 454/Roche FLX genome sequencer

Runs were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions with the following modification. To increase the number of sequencing reads, we passed the normal AMPure Bead Purification for FLX runs, Agencourt Bioscience Corporation, Beverly, MA, USA. We used 70 × 75 PTPs with 16-region gaskets. To obtain more sequencing information, we loaded the single lanes with more than 70 000 DNA beads. Each experiment was processed in a 1/16 run.

Bioinformatic analyses

We mapped sequences against the genomic reference sequence (hg18, March 2006, build 36.1) using MegaBlast, National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/megablast.shtml. Although usually the aim is to maximize the amount of mapped reads, in our analysis, we put strong emphasis on a stringent discrimination between on- and off-target hits. We determined an optimal e-value threshold that maximizes the number of unique hits, as described in Albert et al.2 Reads with multiple hits and significant e-values were considered as non-unique mappings and were excluded from further analysis. Thus, the amount of not mapped reads is the direct consequence of the stringent regime of parameters, enabling optimal on-target off-target discrimination, and not because of other reasons such as contaminations, gaps or low sequencing quality.

Results

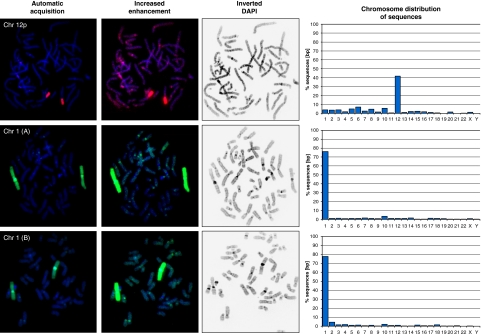

For microdissection, we prepared metaphase chromosomes from human peripheral blood and from lymphoblastoid cells. We targeted human chromosomes 12p and 1. We microdissected 10 short arms from chromosome 12 (experiment Chr 12p) and 6 chromosomes 1. The experiment for chromosome 1 was performed twice (experiments Chr 1(A) and Chr 1(B), respectively). The critical step was amplification from small amounts of starting material, which was successfully done by DOP-PCR. We obtained sufficient amount of DOP-PCR product. Subsequently, we took an aliquot of microdissected and DOP-PCR-amplified material for proof of specificity on control chromosomes (reverse FISH in the left panel of Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Specificity of the microdissected material tested in metaphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and in 454 sequencing. Left panel: specificity of the microdissected material tested on metaphase FISH. On the left, the hybridization signals of the microdissected material are shown as seen under the microscope; material from chromosome 12p and whole chromosome 1 were purified and processed without major contamination. When signal detection was enhanced (middle panel), we saw minor cross-hybridization on other chromosomes, mainly in pericentromeric regions, which have a high degree of homology among chromosomes. The other faint cross-hybridizations might be due to repeat elements and segmental duplications. The inverted DAPI channel shows a GTG-like chromosome banding to unambiguously identify the metaphase chromosomes. Right panel: mappings of sequence reads show enrichment of the targeted chromosomes. A total of 41.8% of reads that uniquely mapped to the whole genome, aligned to targeted chromosome 12p, and 76.2 and 77.6% to targeted chromosome 1 (experiments A and B, respectively). This result documents the feasibility of the microdissection approach. Mapping on other chromosomes might represent repeat elements, transposons, gene families or annotation problems. The higher proportion of off-target hits from the microdissected material from chromosome 12p might result from the lower ratio of specific sequence to repeat-rich heterochromatin, as the microdissected short arm 12p contains a significant amount of pericentromeric heterochromatin. In addition, 12p is known to have been involved in segmental duplications.30, 31, 32, 33 Also, annotation errors due to unclonable genomic regions with subsequent contig gaps might contribute.29 (For each experiments we used 1/16 of a 454/Roche FLX run).

The remaining material was used for the 454 library preparation. Of all obtained sequence reads, about 52, 67 and 55% could be mapped to the human reference genome in experiments chr12p, chr1(A) and chr1(B), respectively (Table 1). For chromosome 12p, ∼42% of sequence reads, that were mapped to the whole genome just once, had their primary BLAST hit in the target region (Table 1, Figure 2 upper right panel, Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 1). In both chromosome 1 experiments, more than 75% of uniquely mapped sequence reads had their hit on chromosome 1 (Table 1, Figure 2 middle and lower right panels, Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1. Analysis of mapped and unmapped sequences regarding the target chromosome and sequence.

| Parameter | Chr 12p | Chr 1(A) | Chr 1(B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obtained sequences (reads; n) | 998 | 1274 | 1416 |

| Unmapped reads (n) | 480 | 423 | 634 |

| Mapped reads (n) | 518 | 851 | 782 |

| Percentage of mapped sequences (%) | 51.9 | 66.8 | 55.2 |

| Reads with unique genomic mapping | 368 | 589 | 550 |

| Mapped sequences on target CHR (n) | 154 | 449 | 427 |

| Percentage of uniquely mapped sequences on target (%) | 41.8 | 76.2 | 77.6 |

| Mapped read sizes on target CHR (bp) | 28 349 | 73 275 | 71 993 |

| Mapped read matches (bp) | 28 243 | 72 856 | 71 579 |

| SNPs (n) | 106 | 419 | 414 |

| SNPs every how many base pairs | 267.44 | 174.88 | 173.90 |

| Mapped sequences outside target (n) | 214 | 140 | 123 |

| Mapped read sizes outside target CHR (bp) | 37 602 | 21 399 | 21 230 |

| Mapped read matches (bp) | 37 481 | 21 285 | 21 156 |

| SNPs (n) | 121 | 114 | 74 |

| Average spacing of detected SNPs (bp) | 310.76 | 187.71 | 286.89 |

It is to be noted that mapped reads contain all mapped reads, that is, unique chromosomal hits and sequences that hit twice or multiple times at different chromosomal positions. (For example, among 851 total-mapped reads in experiment Chr 1(A), 589 reads hit once throughout the genome. Off those 589 sequences, 449 mapped to the target chromosome and 140 outside the target).

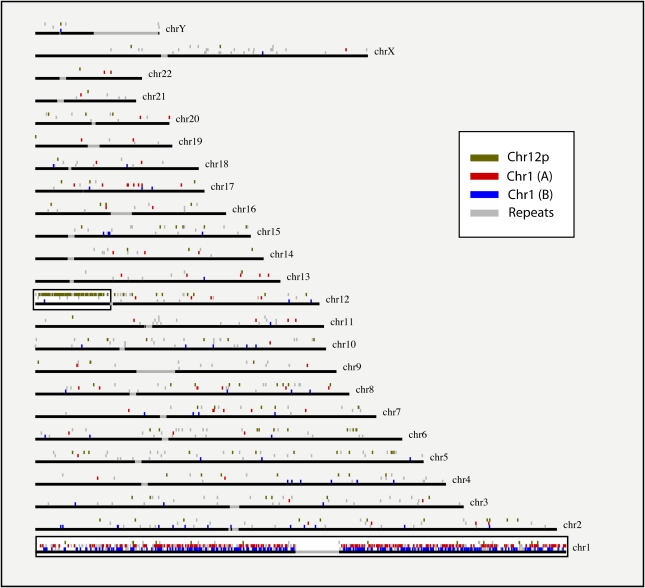

Figure 3.

Distribution of reads mapped to the genome. For each chromosome, we show the unique alignment locations of reads from the three data sets 12p, 1(A) and 1(B) (in olive, red and blue), as well as placements in annotated repeats (gray). The targeted regions (chromosome 1 and the p arm of chromosome 12) are highlighted in white boxes (for a zoom-in of these regions, see Supplemental Figure 1).

The distribution of sequencing coverage (Table 2, Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 1), the number of reads partially containing repeat sequences (Table 3, Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 1) and SNP detection rates (Table 1) were within the expected range for currently available enrichment methods. Although the sequence harvest can be further optimized, we obtained a sufficient number of high-quality reads for a proof of principle. The data show that 454 sequencing, starting from as few as six chromosomes, is feasible.

Table 2. Distribution of multiple sequence coverage (analysis of read clusters).

| Fold coverage | Chr 12p | Chr 1(A) | Chr 1(B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 352 | 579 | 571 |

| 2 | 50 | 76 | 59 |

| 3 | 6 | 20 | 15 |

| 4 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 20 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

In all three experiments, the majority of hit regions was covered only by one read.

Table 3. Analysis of sequence repeat patterns.

| Exp. Chr 12p | Exp. Chr 1(A) | Exp. Chr 1(B) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On target | Off target | On target | Off target | On target | Off target | |

| Sequence reads with | ||||||

| SINE (n) | 16 | 85 | 44 | 10 | 46 | 11 |

| LINE (n) | 48 | 10 | 158 | 41 | 145 | 38 |

| LTR (n) | 29 | 66 | 50 | 12 | 34 | 23 |

| Simple repeat (n) | 2 | 21 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Satellite (n) | 0 | 1 | 6 | 23 | 10 | 4 |

| Total (n) | 95 | 183 | 267 | 87 | 235 | 76 |

| Reads without repeats (n) | 72 | 31 | 182 | 53 | 192 | 47 |

| Total reads (n) | 154 | 214 | 449 | 140 | 427 | 123 |

| Total sequence (bp) | 28 349 | 37 602 | 73 275 | 21 399 | 71 993 | 21 230 |

| Density of repeats (bp) | 298.41 | 205.48 | 274.44 | 245.97 | 306.35 | 279.34 |

SINE, small interspersed repetitive element (such as Alu repeats); LINE, large interspersed repetitive element (such as L1 elements); LTR, long terminal repeat.

The table shows the reads containing repetitive sequences vs those without repeats. On average, we detected one repeat every 300 bp (last line of the table). According to a database analysis, for example, in chromosome 1, there is one repeat every 600 bp on average. Thus, the prevalence of repetitive sequences is slightly overrepresented in our experiments. That might be due to incomplete repeat annotations in the current version of the human genome build as well as to new, not yet annotated private repetitive sequences.

Discussion

We present the feasibility of a cytogenetic-based approach to capture target regions for next-generation sequencing. Direct microdissection of the target region in metaphase chromosomes with subsequent DOP-PCR amplification obtained sufficient material and quality for 454 sequencing from as few as six chromosomes.

We analyzed whether some fragments were sequenced several times by clustering reads. In all three experiments, the majority of hit regions were covered by only one read, indicating a coverage distribution and range for preferential amplification within the expected range. Although the representation of repeat regions in the obtained reads is higher than the average density in the currently available genome annotation, the obtained data seem consistent in light of the many newly detected, probably population-specific or private insertions of repeat elements, as they become available from the Watson and Venter genome or the 1000 Genomes Project, respectively.23, 27 Although it was not the aim of our experiments, analyzing regions with repeat elements might be facilitated by a microdissection approach. However, considering the fact that even more stable regions of the genome, such as exons, require a high sequencing depth,28 exploiting sequence variations in repeat elements will probably warrant an even higher coverage. Their de novo annotation would be facilitated by longer sequencing reads to include sequences adjacent to the repeat.

Making chromosomes visible requires the chromatin to condense and arrange, which happens mainly when cells replicate and prepare to divide (metaphase in cell cycle). Accordingly, direct microdissection of the patient's chromosomes is possible only when dividing cells are available. This state-of-affairs is a limitation. Another point to care for is the risk of contamination, especially during the microdissection process and the first cycles of DOP-PCR. However, single-cell techniques are well established in many pre-implantation diagnostic and tumor microdissection laboratories. The number of generated sequences is probably lower than that in other approaches, but can be increased by optimized loading density and compensated by more runs. Our approach works well for complete chromosomes and partial chromosome arms and regions. Smaller parts can also be microdissected, as was previously shown for microdissection libraries with band-resolutions that were created for chromosome painting.24 Such adaptation might be useful for specific questions. Here, we wanted to cover complete regions, including centromeric regions and repeats. When not required, repeats can be blocked by COT-1 DNA to increase the harvest for unique sequences.

We showed that high-throughput sequencing of microdissected chromosomes is feasible and can be done from a few molecules. The coupling of microdissection and next-generation sequencing is suited for a wide range of applications, including standard mutation detection. Sequencing phase-defined chromosomes allows experimental determination of haplotypes and haplotype blocks. The combination of defined localization information and independency from earlier knowledge of sequence composition in the target region might help in solving annotation problems of repeat rich or non-clonable regions in de novo sequencing.29 The approach might also be relevant in humans, when population-specific insertions are suspected, for tracking down small ‘private' cytogenetic abnormalities in patients or tumor cells and for resequencing of dynamic chromosomal regions, such as telomeres, subtelomeres or pericentromeric heterochromatin.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Kosiura, Isabelle Kühndahl, Christina Roehr and Phillipe Schroeter for their technical expertise. We thank Mathias Meyer for his advice. Friedrich C Luft and Eddy Rubin critically read the manuscript. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG SFB 577 project A4 to KH, LI820/11-1 and LI820/17-1 to TL, Li768/6-1 and 6-2 to THL), the IZKF Jena (Start-up S16), the Stiftung Leukämie and the University Jena supported the study. Katrin Hoffmann received a Rahel Hirsch fellowship from the Charité Medical Faculty.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Bashiardes S, Veile R, Helms C, Mardis ER, Bowcock AM, Lovett M. Direct genomic selection. Nat Methods. 2005;2:63–69. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0105-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert TJ, Molla MN, Muzny DM, et al. Direct selection of human genomic loci by microarray hybridization. Nat Methods. 2007;4:903–905. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges E, Xuan Z, Balija V, et al. Genome-wide in situ exon capture for selective resequencing. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1522–1527. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okou DT, Steinberg KM, Middle C, Cutler DJ, Albert TJ, Zwick ME. Microarray-based genomic selection for high-throughput resequencing. Nat Methods. 2007;4:907–909. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porreca GJ, Zhang K, Li JB, et al. Multiplex amplification of large sets of human exons. Nat Methods. 2007;4:931–936. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman DS, Hovingh GK, Iartchouk O, et al. Filter-based hybridization capture of subgenomes enables resequencing and copy-number detection. Nat Methods. 2009;6:507–510. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis ER. New strategies and emerging technologies for massively parallel sequencing: applications in medical research. Genome Med. 2009;1:40. doi: 10.1186/gm40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird DM, Rowson J, Wynford-Thomas D, Kipling D. Extensive allelic variation and ultrashort telomeres in senescent human cells. Nat Genet. 2003;33:203–207. doi: 10.1038/ng1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemann MT, Strong MA, Hao LY, Greider CW. The shortest telomere, not average telomere length, is critical for cell viability and chromosome stability. Cell. 2001;107:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardopoulou EV, Williams EM, Fan Y, Friedman C, Young JM, Trask BJ. Human subtelomeres are hot spots of interchromosomal recombination and segmental duplication. Nature. 2005;437:94–100. doi: 10.1038/nature04029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmers RJ, Wohlgemuth M, van der Gaag KJ, et al. Specific sequence variations within the 4q35 region are associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:884–894. doi: 10.1086/521986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins RA, Carlson JW, Kennedy C, et al. Sequence finishing and mapping of Drosophila melanogaster heterochromatin. Science. 2007;316:1625–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1139816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernburg AF, Broman KW, Fung JC, et al. Perturbation of nuclear architecture by long-distance chromosome interactions. Cell. 1996;85:745–759. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millington K, Hudnall SD, Northup J, Panova N, Velagaleti G. Role of chromosome 1 pericentric heterochromatin (1q) in pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndromes: report of 2 new cases. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;84:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Spreading of silent chromatin: inaction at a distance. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:793–803. doi: 10.1038/nrg1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316:1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahring S, Rauch A, Toka O, et al. Autosomal-dominant hypertension with type E brachydactyly is caused by rearrangement on the short arm of chromosome 12. Hypertension. 2004;43:471–476. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111808.08715.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunyak VV, Prefontaine GG, Nunez E, et al. Developmentally regulated activation of a SINE B2 repeat as a domain boundary in organogenesis. Science. 2007;317:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1140871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varon R, Gooding R, Steglich C, et al. Partial deficiency of the C-terminal-domain phosphatase of RNA polymerase II is associated with congenital cataracts facial dysmorphism neuropathy syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;35:185–189. doi: 10.1038/ng1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman F, Johansson B, Mertens F. The impact of translocations and gene fusions on cancer causation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrc2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins SA, Laxman B, Dhanasekaran SM, et al. Distinct classes of chromosomal rearrangements create oncogenic ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nature. 2007;448:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nature06024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PJ, Stephens PJ, Pleasance ED, et al. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ng.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise A, Mrasek K, Fickelscher I, et al. Molecular definition of high resolution multicolor banding (MCB) probes: first within the human dna-sequence anchored fish-banding probe set. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:487–493. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.950550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenius H, Carter NP, Bebb CE, Nordenskjold M, Ponder BA, Tunnacliffe A. Degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR: general amplification of target DNA by a single degenerate primer. Genomics. 1992;13:718–725. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90147-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr T, Weise A, Heller A, et al. Multicolor chromosome banding (MCB) with YAC/BAC-based probes and region-specific microdissection DNA libraries. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;97:43–50. doi: 10.1159/000064043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DA, Srinivasan M, Egholm M, et al. The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nature. 2008;452:872–876. doi: 10.1038/nature06884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harismendy O, Ng PC, Strausberg RL, et al. Evaluation of next generation sequencing platforms for population targeted sequencing studies. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R32. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R, Zhu Y, Creevey CJ, Francino MP, Bork P, Rubin EM. Genome-wide experimental determination of barriers to horizontal gene transfer. Science. 2007;318:1449–1452. doi: 10.1126/science.1147112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann J, Valentine M, Kidd VJ, Lahti JM. Localization of chi1-related helicase genes to human chromosome regions 12p11 and 12p13: similarity between parts of these genes and conserved human telomeric-associated DNA. Genomics. 1996;32:260–265. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Gu Z, Clark RA, et al. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science. 2002;297:1003–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1072047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin LG. Evolution of the vertebrate genome as reflected in paralogous chromosomal regions in man and the house mouse. Genomics. 1993;16:1–19. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lu HH, Chung WY, Yang J, Li WH. Patterns of segmental duplication in the human genome. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:135–141. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.