Abstract

Trypanosomatid parasites cause serious diseases among humans, livestock, and plants. They belong to the order of the Kinetoplastida and form, together with the Euglenida, the phylum Euglenozoa. Euglenoid algae possess plastids capable of photosynthesis, but plastids are unknown in trypanosomatids. Here we present molecular evidence that trypanosomatids possessed a plastid at some point in their evolutionary history. Extant trypanosomatid parasites, such as Trypanosoma and Leishmania, contain several “plant-like” genes encoding homologs of proteins found in either chloroplasts or the cytosol of plants and algae. The data suggest that kinetoplastids and euglenoids acquired plastids by endosymbiosis before their divergence and that the former lineage subsequently lost the organelle but retained numerous genes. Several of the proteins encoded by these genes are now, in the parasites, found inside highly specialized peroxisomes, called glycosomes, absent from all other eukaryotes, including euglenoids.

Trypanosomatidae form a serious threat to the health of almost half a billion people, particularly those living in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, where the species Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi cause African sleeping sickness and American Chagas' disease, respectively. In most tropical and subtropical areas of the world, Leishmania spp. are responsible for various manifestations of leishmaniasis. Because of their medical importance, these human parasites have been studied extensively and the sequencing of their entire genomes has been undertaken. All Kinetoplastida, the order to which the trypanosomatids belong, share a unique form of metabolic compartmentation. The majority of the enzymes of the glycolytic pathway are sequestered inside specialized peroxisomes, which have therefore been named glycosomes (1, 2). In addition, these organelles contain a number of enzymes of the hexose-monophosphate pathway as well as enzymes involved in other pathways (2, 3). Here we report the presence, in two trypanosomatids (T. brucei and Leishmania mexicana), of several genes coding for proteins of glycosomes, whereas in each case their nearest nonkinetoplastid homolog codes for either a chloroplast or a cytosolic plant/algal enzyme. Plant-like enzymes with other subcellular localization were also identified in trypanosomatids. Despite the absence in these organisms of any trace of an organelle that resembles a chloroplast, there are a number of reports in the literature of plant-like traits associated with these organisms (4–10), but thus far no attempt has been made to explain these observations by an early acquisition of an algal endosymbiont.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning and Sequencing.

The cloning of the T. brucei genes for fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase) and sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase) and the L. mexicana genes for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) and 6-phosphogluconolactonase (6PGL) was performed as follows. A search in the nucleic acid databases using a query of bacterial and mammalian FBPases revealed the Leishmania major FBPase gene sequence (GenBank/EMBL accession no. AL034389) and a 344-bp T. cruzi EST sequence (accession no. AI110494) that appeared to have most identity with plant SBPases (40% with Arabidopsis thaliana) on a tblastn search in the GenBank database. Based on this latter sequence, two degenerate oligonucleotides were designed. PCR amplification was performed by using genomic DNA from T. brucei stock 427. A major amplified 211-bp product was cloned, sequenced, and used to screen an available genomic library of T. brucei constructed with λGEM11 (Promega) in Escherichia coli (11). A 6-kb PstI fragment from one of the hybridizing phages was subcloned and sequenced (accession no. AJ315077). A 500-bp fragment of the T. brucei FBPase gene was amplified by using two degenerate oligonucleotides specified on the basis of the L. major FBPase sequence. The T. brucei genomic DNA library was screened with this PCR fragment. A 5-kb EcoRV fragment from one of the hybridizing phages was subcloned and sequenced (accession no. AJ315078). A genomic library of L. mexicana strain NHOM/B2/84/BEL46 constructed in E. coli MB406 by using the phage vector λGEM11 (12) was screened with the T. brucei G6PDH gene (13) as a probe. The gene was subcloned and sequenced (accession no. AF374270). Initial attempts to clone the L. mexicana 6PGL gene by screening the library with the corresponding T. brucei gene as a probe were unsuccessful. However, an in silico search in the database of the L. major genome sequence project allowed us to identify the complete 6PGL gene of this species (AL160493). Subsequently, with two degenerate oligonucleotides as primers a 450-bp fragment was amplified by PCR from L. mexicana DNA, subcloned, and sequenced. It was then used to screen the DNA library. A 5.5-kb XhoI fragment was subcloned and the complete ORF of the 6PGL was sequenced (accession no. AF374271). Sequencing was performed using the Beckman CEQ dye terminator cycle sequencing kit and a Beckman Coulter CEQ 2000 DNA Analyzer.

Database Screening.

Sequences generated in the Trypanosome Genome Project (www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/T_brucei/GSS.shtml) were translated in the six reading frames. Sufficiently long ORFs were than compared with all of the protein sequences available in the SWISS-PROT and SwissAll databanks of the EBI server at Hinxton, U.K. (www.ebi.ac.uk), using the blastp program in a search of potential trypanosome enzymes with typical plant-like traits. Trypanosomatid sequences used in the phylogenetic analyses (other than those whose cloning and sequencing is described above), were taken from the SWISS-PROT database where possible. In the remaining cases they were taken from the translated EMBL database. Accession numbers are as follows: adenylate kinase (ADK), AL474359; aldolase, ALF_TRYBB; GAPDH, G3PG_TRYBB; alternative oxidase, AOX_TRYBB; G6PDH, AJ249254 (T. brucei); 6PGL, AJ249255 (T. brucei); AF374271 (L. mexicana); 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGDH), X65623; phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK), PGKC_TRYBB; phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM), AJ243593; α-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase (AHADH), Q9NJT1; glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH), GPDA_ TRYBB; ω-6-fatty acid desaturase, AC007862:101200-102000; acyl carrier protein (ACP), AZ217514; vacuolar H+ pyrophosphatase(V-H+PPase), VATA_TRYCO; and Fe-superoxide dismutase, U90722.

Phylogenetic Analyses.

To identify a “plant affiliation,” positive hits obtained in the blast output were aligned with the translated query sequence using the program clustalw (14). Neighbor-joining and maximum-likelihood trees were constructed for each multiple alignment after the removal of all positions with gaps. For calculation of neighbor-joining trees, clustalx or the programs protdist and neighbor of the phylip package (15) were used. The program treepuzzle (16), employing the jtt (17) correction as an evolutionary model, was used to create maximum-likelihood trees.

Results and Discussion

FBPase and SBPase.

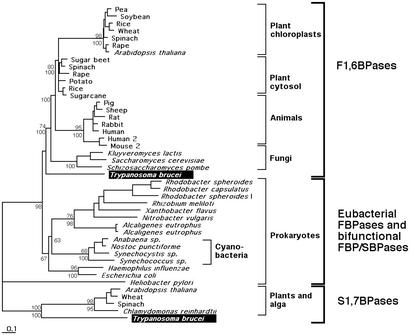

We have used genomic information to search for the presence of genes coding for potential glycosomal proteins as identified by the presence of so-called peroxisome-targeting signals (PTSs), either at their C terminus (PTS1) or near their N terminus (PTS2). Most strikingly, we identified in T. brucei, a gene with a complete ORF for a homolog of SBPase, an enzyme typical of the Calvin cycle of photosynthetic organisms and has been thus far encountered only in the chloroplasts of green algae and plants (18). The inferred protein sequence has a PTS1 (-SKL) at its C terminus, suggestive of a glycosomal localization. In addition, we identified an ORF encoding a FBPase with both a C-terminal PTS1 and an N-terminal PTS2. FBPase is a gluconeogenic enzyme that shares a common ancestry with the SBPases (18). Alignment of the two parasite protein sequences with plant and algal SBPases and with FBPases from bacteria and eukaryotes (Fig. 1) indicated that all residues essential for catalysis have been conserved in both trypanosome enzymes, suggesting that both genes still encode functional proteins. Whereas the T. brucei FBPase branches at the bottom of the eukaryotic clade of the FBPases, indicative of its truly protist nature (Fig. 2), the trypanosome SBPase robustly clusters with the plant and algal (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) SBPases (100% bootstrap support). The trypanosome SBPase gene, therefore, must have been acquired by a horizontal transfer event.

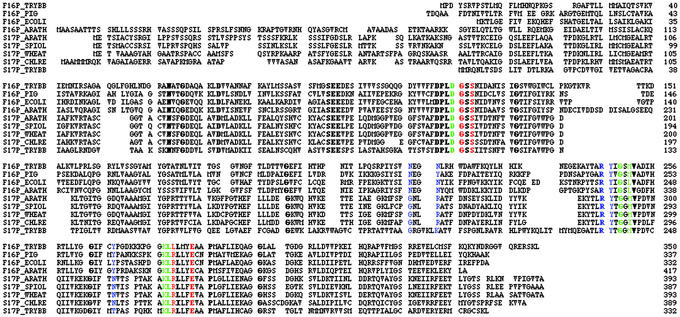

Figure 1.

Alignment of the T. brucei FBPase (F16P_TRYBB) and SBPase (S17P_TRYBB) sequences with three representative FBPases and all of the other SBPases in the SWISS-PROT database. Bold letters mark positions entirely conserved in a full alignment of all of the SWISS-PROT database entries containing the FBPase/SBPase family PROSITE signature. Red, green, and blue shading mark residues interacting with the 1-phosphate, sugar, and 6/7-phosphate moieties of substrate, respectively, as observed by crystallographic analysis of pig liver FBPase (40). Both T. brucei sequences carry a PTS1 (C-terminal -SKL), and the FBPase carries a potential PTS2 (residues 6–13, RVxxxxxQF).

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining tree of SBPases and FBPases. The T. brucei SBPase and FBPase sequences were compared with the complete SWISS-PROT database for homologous sequences by using the BLASTP algorithm. The best scoring 43 homologous protein sequences were aligned by using the program clustalw (14). The alignment, after removal of all regions with insertions and deletions, was used for the creation of a neighbor-joining tree. A maximum-likelihood tree was created by using the program treepuzzle (16) with 1,000 puzzle steps and the JTT correction as an evolutionary model (17). Bootstrap values (1,000 samplings) obtained by the neighbor-joining method are indicated above the branches, while the puzzle frequencies (1,000 puzzle steps) are indicated below the branches. The horizontal bar represents the equivalent of 10 substitutions per 100 residues.

Aldolase.

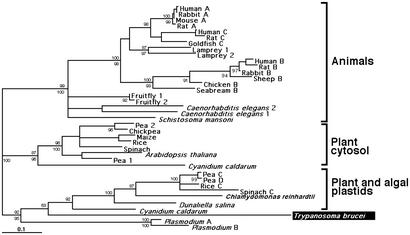

Because there is no evidence for the presence of a functional Calvin cycle in any of the Trypanosomatidae, this SBPase can find its function only in a modified hexose-monophosphate pathway, where it hydrolyzes SBPase, synthesized from erythrose 4-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate through the action of a bifunctional aldolase. Such bifunctional aldolases, capable of forming both FBPase and SBPase by using either glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate or erythrose 4-phosphate as substrate in the condensation reaction with dihydroxyacetone phosphate, have been described only for chloroplasts (19). We then analyzed whether the trypanosomatid aldolases could have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer from a chloroplast as well (Fig. 3). Indeed, Trypanosoma and Leishmania aldolases (20, 21) appear to form a robust (92–95% bootstrap support) monophyletic group with the chloroplast aldolases from both algae and plants. The trypanosomatid enzymes are most closely related to the enzymes of the rhodophyte alga Cyanidium caldarum, the chlorophyte algae Dunaliella salina, and C. reinhardtii. Moreover, the A and B isoenzymes of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, form a sister group of both the trypanosomatid and the chloroplast aldolases. Here it should be noted that the Apicomplexa, to which P. falciparum belongs, still contains the remnant of a plastid, called the apicoplast (22).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of FBPase aldolases. The T. brucei FBPase aldolase sequence was compared with the complete SWISS-PROT database for homologous sequences using the blastp algorithm. The best scoring 37 protein sequences were aligned by using the program clustalw (14). Neighbor-joining and maximum-likelihood trees were prepared as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Neighbor-joining bootstrap values are indicated above the branches, and puzzle frequencies (1,000 puzzle steps) are indicated below the branches. The horizontal bar represents the equivalent of 10 substitutions per 100 residues.

Horizontal Transfer of Other Genes.

These findings prompted us to investigate whether trypanosomatids contain other genes that could have been acquired by horizontal transfer. The genes present in the database, or referred to in the literature (4–10), for which a plant, chloroplast, or cyanobacterial affiliation could be inferred, are summarized in Table 1 (see also www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html). Krepinsky et al. (8) recently reported that the first enzyme of the hexose–monophosphate pathway (HMP) in trypanosomes, G6PDH, is most related to homologs found in the plant cytosol. In trypanosomes, this enzyme is present in both the cytosol and in glycosomes (23). The second HMP enzyme, 6PGL, which in T. brucei is partly present in glycosomes, which carries a PTS1 (13) and the L. mexicana enzyme, which carries a putative PTS2 consisting of a nonapeptide close to its N terminus, by contrast, seem to be of bacterial origin and cluster with cyanobacteria (www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html). Krepinsky et al. (8) also demonstrated a relationship between plastid and the T. brucei 6PGDH (24), and our analyses confirmed a bacterial origin. The T. brucei 6PGDH branched closely to its homolog from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. (www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html), but such a relationship was not recovered in a different analysis (25). Cyanobacteria are considered to be closely related to the precursor of all chloroplasts in plants and algae.

Table 1.

Plant-like enzymes and enzymes of possible cyanobacterial origin in Trypanosomatidae

| Enzyme | Function in alga | Location in alga (plastid or cytosol) | Function in trypanosomatid | Glycosomal location in trypanosomatid | Ref(s). |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBPase | Calvin cycle | P | HMP? | + | |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) | HMP | C | HMP | + | 13 |

| 6PGL | HMP | P | HMP | + | 13 |

| 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGDH) | HMP | P | HMP | 24 | |

| Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (ALD) | Calvin cycle | P | Glycolysis | + | 20, 21 |

| GAPDH | Calvin cycle | P | Glycolysis | + | 28, 29 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) | Calvin cycle | P | Glycolysis | + | 23 |

| PGAM | Glycolysis | C | Glycolysis | 7 | |

| α-Hydroxyacid dehydrogenase (AHADH) | Glyoxylate cycle | C | Aromatic amino acid metabolism | 5 | |

| G3PDH | Glycerol metabolism | P | Glycerol metabolism | + | 31 |

| Alternative oxidase | Respiration | Mitochondrion | Respiration | 9 | |

| Vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase (V-H+-PPase) | H+ pump | Vacuole | H+ pump | 6 | |

| ω-6-Fatty acid desaturase | Fatty acid synthesis | ER? | Fatty acid synthesis | 4 | |

| Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | ROS protection | P | ROS protection | + | |

| ACP | Fatty acid synthesis | P | Fatty acid synthesis | 26, 27 | |

| Adenylate kinase (ADK) | Energy balance | P | Energy balance | + |

HMP, hexose-monophosphate pathway; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ROS, reactive oxygen species. Supplementary material is available at www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html.

A 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3BPGA)-independent PGAM, typically found in the cytosol of plants, and unrelated to the 2,3BPGA-dependent enzyme normally found in most nonphotosynthetic eukaryotes, has a homolog in T. brucei as well (ref. 7 and www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html). This cofactor-independent enzyme clusters with the plant cytosolic PGAMs, rather than with the prokaryotic PGAMs.

Phylogenetic analysis showed a robust affinity (92% bootstrap support in neighbor-joining analysis) of a T. brucei adenylate kinase bearing a PTS1 with that of maize chloroplasts. A T. cruzi aromatic α-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase, a member of the family of malate dehydrogenases (MDHs) (5) but distinct from the mitochondrial and glycosomal MDHs of trypanosomatids, was most closely related to the MDH homologs from plant cytosol. A T. brucei cyanide-insensitive alternative oxidase, homologous to the alternative oxidases of plants and fungi (9), also clustered robustly with the oxidase of plants (see www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html).

Lipid metabolism in the Trypanosomatidae has plant-like traits as well. Like Euglena, trypanosomatids synthesize polyunsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid (4). Enzymes involved in the synthesis of these fatty acids are ω-3 and ω-6 fatty-acid desaturases, the genes of which have so far been described only for plants and fungi. We searched the T. brucei genome database and found a gene for an ω-6 fatty-acid desaturase homologous to that of soybean (www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html), whereas homologs from organisms other than plants could not be detected in the protein database. T. brucei also has an ACP involved in the type II fatty acid-biosynthetic pathway, typical of plants and bacteria (26, 27). This T. brucei ACP branched with the ACP of A. thaliana (www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html).

Both Trypanosomatidae and the Apicomplexa contain subcellular organelles, rich in calcium and pyrophosphate, called acidocalcisomes (6, 10). These organelles share properties with the vacuoles of plants and they all are characterized by the presence in their membranes of a typical proton pump, the vacuolar proton-dependent pyrophosphatase (V-H+PPase). The trypanosomatid V-H+PPase enzymes were robustly monophyletic with those of the plastid-bearing apicomplexans Toxoplasma gondii and P. falciparum, plants (6), and the chlorophyte C. reinhardtii (www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html).

Results from analyses for several other genes also provide indications toward events of horizontal transfer, but are only suggestive of a possible relationship with algae, chloroplasts, or cyanobacteria. Trypanosomatid GAPDH and its counterpart from Euglena gracilis are close relatives of the GAPDH isoenzyme 1 from cyanobacteria, but are clearly distinct from the plastid GAPDH of plants, which has been derived from the cyanobacterial isoenzyme 3 (28, 29). The three closely related trypanosomatid PGK isoenzymes (30) are clearly distinct from their eukaryotic homologs, including those of protists such as the ciliates Tetrahymena and Euplotes and the apicomplexan Plasmodium, in that they lack a typical eukaryotic 11-aa insertion (www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html), and in a phylogenetic analysis they clustered robustly with the prokaryotic sequences, including the cyanobacterial ones. For the trypanosomatid G3PDH, while also of clear prokaryotic origin (31), the phylogenetic signal of the data set did not allow the identification of the prokaryote from which the gene could have been derived. A similar observation was made for a PTS1-containing Fe-superoxide dismutase (SOD) which clustered with the Fe- and Mn-SODs from bacteria and those of chloroplasts (www.icp.ucl.ac.be/∼opperd/Supplementary/table.html).

Did Trypanosomatidae Secondarily Acquire an Algal Endosymbiont?

Trypanosomatids apparently bear a considerable number of plant-like enzymes. Some of them are related to their cyanobacterial and chloroplast homologs, whereas others more closely resemble their homologs that are found in the plant cytosol. Because the free-living Kinetoplastida such as the bodonids are phagotrophic predators that feed on bacteria, our observations may be explained by Doolittle's “You are what you eat” hypothesis (32). However, keeping in mind that the closely related Euglenida have chloroplasts surrounded by three membranes, which are supposed to have been acquired by a mechanism of secondary endosymbiosis, in the case of the Trypanosomatidae, the most parsimonious explanation would be that the genes of all these enzymes have entered the ancestor through a single event of endosymbiosis with an alga. Because chloroplasts, or remnants thereof, have not been detected in any of the extant members of the Kinetoplastida, it is most likely that a common ancestor of both the Euglenida and the Kinetoplastida had already acquired this endosymbiont. Whereas in the Euglenida, the chloroplast was retained as the only remnant of the alga, in the ancestor of the Kinetoplastida the endosymbiont, with its chloroplast, was lost, but only after many of its nuclear and chloroplast genes had been transferred to the host's nucleus.

The acquisition of plastids by secondary endosymbiosis, and the subsequent loss of an entire organelle, or parts of it, is not unprecedented. Several groups of eukaryotes are believed to have secondarily lost their plastids, of which the oomycetes are probably the most notable example (33). Remnants of a plastid have also been discovered in the Apicomplexa (Plasmodium and Toxoplasma; cf. ref. 22). This so-called apicoplast still contains a small genome reminiscent of that found in chloroplasts. The organelle is bounded by four membranes, thus providing additional evidence that it arose from a secondary endosymbiosis event.

What Is the Origin of the Glycosome?

A relatively large part of the enzymes described above, and that seem to have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer (9 of 16), are found in glycosomes (Table 1). These organelles, which are unique to the Kinetoplastida, are absent from Euglenida (34). However, it is unlikely that these glycosomes could represent the remnant of the plastid supposed to be originally present in the kinetoplastid ancestor. Glycosomes are bounded by a single membrane and they bear no DNA. Moreover, glycosomal proteins enter their organelle with the help of targeting signals that are shared with other members of the microbody family, such as peroxisomes and glyoxysomes (35). This finding suggests that glycosomes are true peroxisomes and thus are not the relics of a plastid.

The loss of the algal endosymbiont must have been accompanied by the recruitment of part of the algal metabolic enzymes by the host. A relatively high proportion of plant-like enzymes, including those of the glycolytic pathway, were sequestered inside peroxisomes, which then became glycosomes. We assume that this transfer of enzymes from the endosymbiont has occurred “en bloc,” because the formation of a functional pathway through a successive transfer of individual enzymes to the organelle is highly unlikely. As argued (36, 37), intermediate stages would not be an advantage to the host organism but, rather, would be a burden. The mechanism by which such en bloc transfer would have taken place is not clear. Genes from the endosymbiont, from either its nucleus or its chloroplast, were transferred either to the host nucleus or were lost. A direct fusion between a peroxisome and the alga or its chloroplast could have triggered the transfer of enzymes and the subsequent acquisition of a PTS by the encoded polypeptides would have been a relatively minor step in evolution. The glycosomal enzymes of the extant trypanosomatids involved in glycolysis and HMP may have originated from the endosymbiont's cytosolic enzymes involved in similar processes, or from those of its chloroplast, where similar reactions are catalyzed by enzymes of the Calvin cycle. The acquisition of a PTS either by enzymes encoded by the transferred genes from the endosymbiont or by original host genes may have resulted in the organelles' present-day mosaic appearance (Table 1). The relocation of a large number of algal enzymes has drastically changed the metabolic functions of the original peroxisome and has been a crucial step toward the formation of the present-day glycosome, an organelle that has carbohydrate catabolism as its major function.

In Plasmodium the discovery of the apicoplast has led to the identification of new targets for the treatment of malaria such as the enzymes required for the synthesis of isoprenoids (38) and a plant-like type II fatty acid-biosynthetic pathway (39). Similarly, in the case of T. brucei it has recently been reported (40) that thiolactomycin effectively retarded cell growth by inhibition of a similar type II-biosynthetic pathway. The identification of a plant-like ACP, likely to be involved in this pathway, agrees well with these reports. The presence in trypanosomatids of enzymes and, perhaps, complete pathways of algal origin opens new perspectives for the identification of targets for new therapeutics. A wide range of agricultural herbicides are available for screening of activity against trypanosomes and leishmanias.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathalie Blondeel, Petra Slanc, Nathalie Chevalier, and Joris van Roy for help with some of the cloning, sequencing, and sequence analysis work. This work was supported by grants from the Belgian Prime Minister's Inter-University Attraction Poles program and the European Union 4th Framework International Cooperation with Developing Countries (INCO-DC) Program.

Abbreviations

- ACP

acyl carrier protein

- 6PGL

6-phosphogluconolactonase

- FBPase

fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase

- PGAM

phosphoglycerate mutase

- PTS

peroxisome-targeting signal

- PTS1

PTS at the C terminus

- PTS2

PTS near the N terminus

- SBPase

sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase

- G3PDH

glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases [accession nos. AJ315077 (T. brucei SBPase), AJ315078 (T. brucei FBPase), AF374270 (L. mexicana G6PDH), and AF374271 (L. mexicana 6PGL)].

See commentary on page 765.

References

- 1.Opperdoes F R, Borst P. FEBS Lett. 1977;80:360–364. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)80476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opperdoes F R. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:127–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michels P A M, Hannaert V, Bringaud F. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:482–489. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01810-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korn E D, Greenblatt C L. Science. 1963;142:1301–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.142.3597.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cazzulo Franke M C, Vernal J, Cazzulo J J, Nowicki C. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:903–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drozdowicz Y M, Rea P A. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:206–211. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01923-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chevalier N, Rigden D J, Van Roy J, Opperdoes F R, Michels P A M. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:1464–1472. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krepinsky K, Plaumann M, Martin W, Schnarrenberger C. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2678–2686. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhuri M, Hill G C. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;83:125–129. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Docampo R, Moreno S N J. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;114:151–159. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michels P A M, Marchand M, Kohl L, Allert S, Wierenga R K, Opperdoes F R. Eur J Biochem. 1991;198:421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannaert V, Blaauw M, Kohl L, Allert S, Opperdoes F R, Michels P A M. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;55:115–126. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffieux F, Van Roy J, Michels P A M, Opperdoes F R. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27559–27565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein J. phylip (Phylogeny Inference Package) (Univ. of Washington, Seattle), Version 3.5c. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strimmer K, von Haeseler A. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:964–969. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones D T, Taylor W R, Thornton J M. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin W, Abdel-Zaher M, Henze K, Schnarrenberger C. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:485–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00019100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flechner A, Gross W, Martin W F, Schnarrenberger C. FEBS Lett. 1999;447:200–202. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchand M, Poliszczak A, Gibson W C, Wierenga R K, Opperdoes F R, Michels P A M. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;29:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Walque S, Opperdoes F R, Michels P A M. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;103:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson R J M. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:257–274. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heise N, Opperdoes F R. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;99:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett M P, Le Page R W F. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;57:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90247-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson J O, Roger A J. Curr Biol. 2002;12:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita Y S, Paul K S, Englund P T. Science. 2000;288:140–143. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul K S, Jiang D, Morita Y S, Englund P T. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(01)01984-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figge R M, Schubert M, Brinkman H, Cerff R. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:429–440. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fast N M, Kissinger J C, Roos D S, Keeling P J. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adjé C, Opperdoes F R, Michels P A M. Gene. 1998;217:91–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohl L, Drmota T, Do Thi C-D, Callens M, Van Beeumen J, Opperdoes F R, Michels P A M. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;76:159–173. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doolittle W F. Trends Genet. 1998;14:307–311. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavalier-Smith T. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:174–182. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opperdoes F R, Nohynkova E, Van Schaftingen E, Lambeir A M, Veenhuis M, Van Roy J. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;30:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clayton C, Haüsler T, Blattner J. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:325–344. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.325-344.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borst P, Swinkels B W. In: Evolutionary Tinkering in Gene Expression. Grunberg-Manago M, Clark B F C, Zachau M G, editors. New York: Plenum; 1989. pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michels P A M, Opperdoes F R. Parasitol Today. 1991;7:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90167-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Sanderbrand S, Altincicek B, Weidemeyer C, Hintz M, Türbachova I, Eberl M, Zeidler J, Lichtentahler H K, et al. Science. 1999;285:1573–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridley R G. Science. 1999;285:1502–1503. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Liang J Y, Huang S, Ke H, Lipscomb W N. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1844–1857. doi: 10.1021/bi00058a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]