Abstract

Léri-Weill Dyschondrosteosis (LWD) is a dominant skeletal disorder characterized by short stature and distinct bone anomalies. SHOX gene mutations and deletions of regulatory elements downstream of SHOX resulting in haploinsufficiency have been found in patients with LWD. SHOX encodes a homeodomain transcription factor and is known to be expressed in the developing limb. We have now analyzed the regulatory significance of the region upstream of the SHOX gene. By comparative genomic analyses, we identified several conserved non-coding elements, which subsequently were tested in an in ovo enhancer assay in both chicken limb bud and cornea, where SHOX is also expressed. In this assay, we found three enhancers to be active in the developing chicken limb, but none were functional in the developing cornea. A screening of 60 LWD patients with an intact SHOX coding and downstream region did not yield any deletion of the upstream enhancer region. Thus, we speculate that SHOX upstream deletions occur at a lower frequency because of the structural organization of this genomic region and/or that SHOX upstream deletions may cause a phenotype that differs from the one observed in LWD.

Keywords: SHOX, short stature, Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis, enhancer, homeobox gene

Introduction

Léri-Weill Dyschondrosteosis (LWD) is a dominantly inherited skeletal dysplasia characterized by disproportionate short stature and a symptomatic bowing of the radius known as Madelung deformity.1, 2 Depending on the population analyzed, between 60–90% of LWD cases are caused by haploinsufficiency of the short stature homeobox gene (SHOX), which is situated in the pseudoautosomal region of the human sex chromosomes.3, 4, 5 SHOX encodes a homeodomain transcription factor and is strongly expressed in developing limb buds and in fetal and prepubertal growth plates, suggesting a role in bone development. In addition to its function underlying the growth and skeletal deficits of LWD and Langer syndrome,1, 2 SHOX haploinsufficiency is also the primary cause of short stature in Turner Syndrome6 and in about 5–15% of patients diagnosed clinically as having idiopathic short stature.7, 8, 9 On the basis of screening studies published to date, the overall prevalence of SHOX deficiency in the normal population is estimated to be approximately 1–3 in 1000 individuals.

Recently, convincing evidence for an enhancing function of a 100–300 kb region downstream of the SHOX gene was provided by the analysis of patients with an intact SHOX coding region but with deletions downstream of the gene.7, 9, 10, 11, 12 Comparative genomic analyses identified several highly conserved non-coding DNA elements within the deleted interval, which were subsequently shown to act as enhancers in the chicken limb bud.10 Enhancer elements are necessary for the temporal and tissue-specific expression of developmentally important genes such as SHOX.

Several studies reported deletions downstream of SHOX at a frequency of roughly 15–45% in LWD patients;7, 9, 11 however, information about upstream deletions in LWD patients is lacking. In our study, we investigated the functional relevance of the upstream region of SHOX using two different in vivo enhancer assays in chicken limb and cornea and screened LWD patients for deletions in this interval.

Methods

Comparative genomic analysis

Vertebrate sequences orthologous to the human SHOX locus were retrieved from the ECR browser (http://ecrbrowser.dcode.org). The criteria for the identification of conserved elements were the following: minimal length of 100 bp and minimal sequence identity of 70%. For all alignments, the human DNA sequence (NCBI build 36.1; Hg 18) served as a reference.

Highly Conserved Non-coding Elements (CNEs) upstream of SHOX were numbered serially from −1 to −5. Four CNEs (CNE-2, CNE-3, CNE-4 and CNE-5) were selected for functional analysis, all of which were also conserved in distantly related species such as chicken, fugu or zebrafish.

Plasmid constructs

The conserved non-coding sequences of CNE-2, CNE-3, CNE-4 and CNE-5 were amplified by PCR out of human genomic DNA as a template with the following primers:

CNE-2 for: AATAGATCTACATGACAGCCGGGCCTCTG

CNE-2 rev: AGCGAATTCGCGAGCCATAAAACAAGCTG

CNE-3 for: GCCAGATCTCGAGGTGGATCAAAGTGTCA

CNE-3 rev: GGCGAATTCTGCTCTGCCATATCCTCAATC

CNE-4 for: GCGAGATCTTAGATAAGGGACCTCCTCTG

CNE-4 rev: CGCGGAATTCGATTTTCTGGCTGGAAATGG

CNE-5 for: CGCGGATCCCAAACACGGAACAGCACACT

CNE-5 rev: GGCGAATTCTCTCCGCCTCTTCGGCAGA

PCR products were cloned into the pSTBlue-1/Acceptor vector (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) and then subcloned into the vector Bg-EGFP13 after digestion with EcoRI and BglII or BamHI.

Chicken in ovo electroporations and enhancer reporter expression analysis (in ovo enhancer assay)

For the enhancer assay, selected conserved non-coding elements were cloned into a reporter construct (vector Bg-EGFP) upstream of the β-globin promoter driving the expression of green fluorescent protein (Figure 2B). The β-globin promoter is weak and has no basal activity in the absence of an enhancer element. Thus, the β-globin promoter is only active if the vector contains a functional enhancer element. The activity of the promoter and hence the activity of the enhancer can be monitored by the detection of GFP expression. As a control for electroporation efficiency, an RFP reporter construct was co-electroporated. The exact procedure and conditions for electroporations of developing chicken limb buds are described in Sabherwal et al.10

For the functional analysis of CNEs in developing chick cornea, stage HH25 embryos were electroporated with the respective GFP reporter constructs for CNE-2 to CNE-5. Platinum electrodes were positioned with the cathode placed adjacent to the cornea of the right eye and the anode behind the head. A Hamilton needle with a blunt syringe was used to dispense 0.5 μl of a DNA-glycerol mix (containing 17% GFP reporter construct, 17% RFP expression construct, 65% glycerol, 1% fast green) onto the cornea of the right eye of the embryo. The needle was quickly withdrawn and an electric current of 65 V for 50 ms was immediately applied five times. Corneas were analyzed as whole mounts for GFP and RFP expression 24 h after electroporation.

Collection of patients' material

LWD patients were recruited by experienced endocrinologists. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their parents. Mutations/deletions of the coding region of SHOX and deletions of the downstream region of SHOX were ruled out in previous studies.8, 9, 10

Structural analyses of the genomic regions upstream and downstream of SHOX

The SHOX upstream and downstream regions were analyzed for interspersed repeats and GC content using the RepeatMasker platform (http://www.repeatmasker.org based on genome assembly hg18). For the SHOX upstream region, the entire distal part of the X/Y chromosome from the telomere to the promoter region of SHOX (chrX/Y: 0–500 000) was included. For the SHOX downstream region, the same number of basepairs was analyzed, encompassing the majority of the downstream deletion break points reported so far (chrX/Y: 550 000–1 050 000).7, 10, 11, 12

Deletion screening of the SHOX upstream region in patients

In total, 60 patients were screened for deletions of the SHOX upstream region. Screening methods were chosen according to the availability of patients' material.

Genomic DNA for SNP analysis was available for 52 patients. Fifty-eight SNPs spanning the region chrX/Y: 269.722–504.956 were analyzed for sequence heterozygosity (Supplementary Table 1). For eight patients, only metaphase spreads were available. We therefore performed FISH using the following cosmids to screen for upstream deletions: H032 (LLNLc110H032; chrX/Y: 217 700∼252 000), 25D05 (LLN0YCO3′M'25D5; chrX/Y: 297 700∼334 000), 43C11 (LLN0YCO3′M'43C11; chrX/Y: 405 400∼439 000) and 15D10 (LLN0YCO3′M'15D10; chrX/Y: 489 000∼527 000). Genomic cosmid locations are given according to NCBI build 36.1; Hg 18.

For 15 of the above mentioned patients, both genomic DNA and metaphase spreads were available. In these patients, both FISH and SNP screening led to the same results.

In situ hybridizations on chicken embryos

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was carried out as reported.14 Sections of whole-mount in situ hybridizations were produced using a vibratome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Results

Identification and functional analysis of conserved elements within the upstream region of the SHOX gene

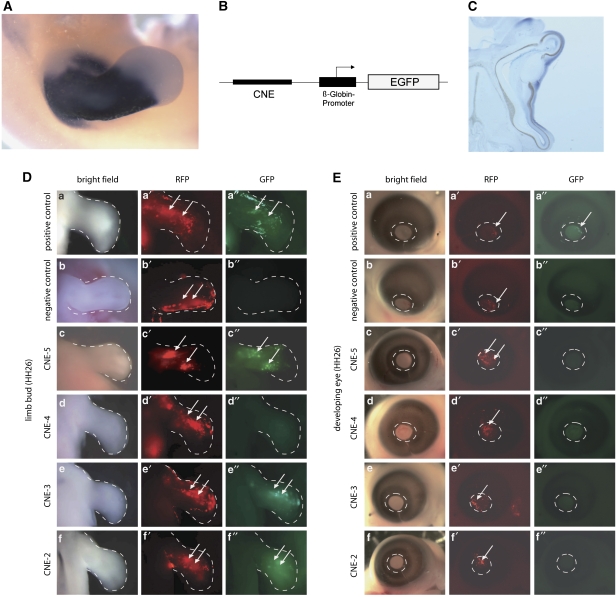

To investigate the functional relevance of the upstream region of SHOX, the entire 500 kb interval adjacent to the telomere was analyzed for conserved non-coding elements (CNEs) using the ECR browser. Multiple sequence alignments revealed a region between chrX: 300 000 and 500 000, with several sequences that are conserved throughout all vertebrate organisms analyzed, including chicken, amphibia and fish. The content of conserved elements in this genomic interval is similar to the downstream region of SHOX, which has a proven enhancer function (Figure 1). Four of the most highly conserved non-coding elements (CNE-2, CNE-3, CNE-4 and CNE-5) were selected for functional analysis in chicken embryos using an in ovo enhancer assay (Figure 2; Table 1). This technique allows the introduction of exogenous DNA into the desired region of the developing chicken embryo.10 The chicken is therefore a valuable model for the study of Shox, especially as there is no Shox homolog in the mouse. Enhancer reporter constructs were electroporated into the limb bud of developing chicken embryos at stage HH19. The expression of GFP (reporting enhancer activity of the tested CNE) and RFP (control for electroporation efficiency) was monitored 2 days later at a developmental stage (HH26) in which Shox was found to be expressed endogenously in the chicken limb bud (Figure 2A and Tiecke et al15). RFP expression was detected throughout the limb, indicating expression of the electroporated construct. GFP expression was detected in limb buds electroporated with the positive control (Figure 2D a–a′′) but was not present in limbs electroporated with the negative control (Figure 2D b–b′′), indicating that the β-globin promoter was functional but only in the presence of an enhancer. GFP expression was detected for CNE-2, CNE-3 and CNE-5, but not for CNE-4 (Figure 2D c′′–f′′). This shows that the region upstream of SHOX contains at least three elements with enhancer activity in the developing limb.

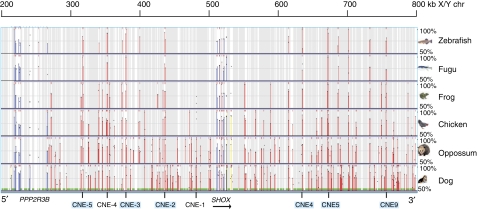

Figure 1.

Comparative genomic analysis of the SHOX genomic region using the ECR browser (data according to the March 2006 human reference sequence hg 18, NCBI Build 36.1). Conserved coding elements are shown as blue or yellow bars, conserved non-coding elements are given as red bars. The height of the bars indicates the degree of conservation between the different species, the width of the bars indicates the size of the conserved elements. Four highly conserved elements in the upstream region (CNE-2, CNE-3, CNE-4 and CNE-5) were selected for analysis in the enhancer assays. The CNEs found to act as enhancers in the limb bud are highlighted in light blue.

Figure 2.

Functional analysis of upstream conserved non-coding elements (CNEs) in chicken limb bud and eye. (A) Shox expression pattern in developing chicken limb (HH26). Whole-mount in situ hybridization shows a strong and specific staining pattern excluding the most distal third of the limb bud. (B) Schematic representation of the vector constructs used to analyze enhancer activity of CNEs in chicken embryos. (C) Shox expression in developing eye (HH26) with specific staining in the cornea. (D) Results of the enhancer assay in chicken limb bud. Pictures show whole mounts of stage HH26 chicken limbs. RFP expression (red) indicates the area electroporated. GFP signal (green) indicates enhancer activity of the tested CNE. A vector containing an SV40 enhancer served as a positive control (a′′, note GFP expression), an empty Bg-EGFP vector served as a negative control (b′′, note lack of GFP expression despite good RFP expression). GFP was detected for three of the four tested CNEs (c′′, e′′, f′′). (E) Result of the enhancer assay in developing chicken eye. Pictures show whole mounts of stage HH26 chicken eyes, circle outlines the cornea. A GFP signal was only detected for the positive control (a′′). As a further control, enhancer activity of non-conserved non-coding elements with comparable CG content was monitored in chicken limb buds (NCE 1: 661 bp, 41% CG; NCE2: 850 bp, 41% NCE3: 480 bp, 43% CG; NCE4: 600 bp, 47% CG). None of these electroporations (23 in total) resulted in a GFP signal, confirming that enhancer activity of CNEs is necessary to evoke a positive signal (control data published in Sabherwal et al10).

Table 1. Summary of the size and position of the tested CNEs (NCBI build 36.1), their homology to chick and the results of the enhancer assay.

| Human | CNE-5 | CNE-4 | CNE-3 | CNE-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 550 | 181 | 386 | 620 |

| Position in the genome | chrX: 318 357–318 906 | chrX: 353 488–353 668 | chrX: 380 279–380 664 | chrX: 436 610–437 229 |

| GC content | 57% | 44% | 44% | 46% |

| Homology to chick | 72% | 83% | 71% | 76% |

| GFP expression in the limb bud | +(18/18) | −(0/13) | +(6/7) | +(5/9) |

| GFP expression in the cornea | −(0/7) | −(0/6) | −(0/7) | −(0/4) |

The results are stated as enhancer activity detected (+) or no enhancer activity detected (−). Number of positive cases/total number of cases are given in brackets.

Patient screening and subsequent structural and functional analysis of the SHOX upstream region

Using FISH and SNP analysis, we screened a cohort of 60 LWD patients for deletions upstream of the SHOX-coding region, in which mutations or deletions of the SHOX coding region and SHOX downstream deletions had been ruled out in previous studies.8, 9, 10 No deletion was found that exclusively affected the upstream region of SHOX. Compared with the high overall frequency of SHOX downstream deletions in LWD, this result was surprising.

One possible explanation for this phenomenon could be that deletions of the upstream region occur less frequently because of structural genomic differences between the two regions. A comparative analysis of the SHOX upstream and downstream region using the RepeatMasker platform revealed the overall content of interspersed repeats of the SHOX downstream region to be considerably higher than that of the upstream region, which could contribute to the high deletion frequency found in the SHOX downstream region. Moreover, the GC content is notably different in the two regions (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the SHOX upstream and downstream region.

| Upstream region of SHOX (ChrX/Y: 0–500 000) (%) | Downstream region of SHOX (ChrX/Y: 550 000–1 050 000) (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Interspersed repeats | 32.94 | 41.43 |

| -SINE | 21.63 | 26.45 |

| -LINE | 4.79 | 6.69 |

| -Others | 6.52 | 8.29 |

| Satellites | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Simple repeats | 3.63 | 5.79 |

| Low complexity | 2.57 | 2.73 |

| GC content | 51.34 | 45.84 |

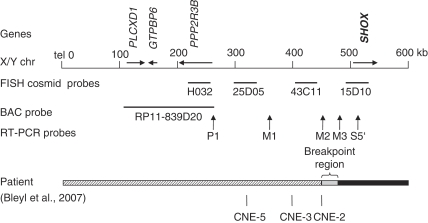

Another explanation for the lack of identified SHOX upstream deletions could be that the limb phenotype in patients with upstream deletions differs from LWD so that these patients were not included in the LWD screening. Support for this idea comes from a recent report on a patient with a unique severe skeletal dysplasia similar to, but yet distinct, from LWD, and an additional eye phenotype (Peters anomaly). In the index patient, a pericentric inversion of the X chromosome led to the disruption of the upstream region of SHOX.16 The telomeric part of the X chromosome distal to SHOX was translocated to a different chromosomal context, resulting in the loss of all three upstream enhancers (CNE-2, CNE-3 and CNE-5), whereas the coding region of the SHOX gene was preserved (Figure 3). The skeletal dysplasia was suggested to result from a misexpression of SHOX due to the loss of unknown putative regulatory elements. The data obtained with the in ovo enhancer assays verify this assumption (Figure 2D). The additional eye symptoms of the patient were explained as being due to the second break point of the pericentric inversion, which affected the SOX3 gene.16 As in situ hybridization revealed that SHOX is also expressed in the developing eye and cornea (Figure 2C) and therefore could also be considered to cause the eye phenotype, we decided to reassess this hypothesis and analyze the SHOX upstream CNEs for potential enhancer function in the developing cornea. We carried out an in ovo enhancer assay in the developing cornea (HH25-26) using the same reporter constructs that we previously used in limb bud experiments (Figure 2 and Table 1). Although we obtained GFP expression for the positive control, we could not detect GFP expression for any of the CNE constructs after electroporation (Figure 2E). This indicates that CNEs −2 to −5 upstream of SHOX do not function as enhancers in the chicken cornea at this stage of development.

Figure 3.

The upper part of the figure shows a schematic representation of the telomeric region of the X chromosome with all known genes. The middle part of the figure depicts different markers that were used to define the position of the deletion break point in the patients (index patient and her son) as reported by Bleyl et al (2007).16 In the son, BAC RP11-839D20 was found to be deleted in a comparative genomic hybridization experiment (CGH). Higher resolution mapping of the break point region was carried out by genomic RT-PCR. Probes P1, M1 and M2 mapped within the deleted region, probes M3 and S5′ in the non-deleted region. The lower part of the figure shows the situation in the index patient's DNA (black bar = present, hatched = translocated to Xq, gray = break-point region) and the position of enhancers identified in our study. CNE-5, CNE-3 and CNE-2 are situated in the translocated region. The lack of these enhancers could explain the skeletal phenotypes observed in the patient (figure adapted from Bleyl et al16). Cosmids H032, 25D05, 43C11 and 15D10 represent the FISH probes that were used to screen 15 of the 60 LWD patients for upstream enhancer deletions.

In summary, all four upstream CNEs tested showed no enhancer activity in the developing cornea, whereas three out of four CNEs showed enhancer activity in the developing limb.

Discussion

Conserved non-coding elements can pinpoint enhancer sequences that have an important role in regulating the expression of developmental genes. Disruptions of cis-regulatory elements are associated with a number of different disorders such as polydactyly, aniridia and Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis.10, 17, 18 For several genes, including PAX6 and SOX9, functional enhancers have been shown to reside both upstream and downstream of the coding region.19, 20, 21 We have analyzed the upstream region of SHOX for its regulatory relevance and have identified three CNEs that have enhancer activity in the developing chicken limb bud but not in the developing cornea.

These enhancers next to SHOX are likely to be involved in regulating the specific SHOX expression pattern during development; however, we cannot totally exclude the possibility that the limb bud enhancers we identified act as regulators of another gene, for instance the nearby gene PPP2R3B, encoding a subunit of a Ser/Thr phosphatase. However, enhancers are typically found next to genes involved in development, where they regulate the temporal and spatial expression patterns required during development. Therefore, the identified limb enhancers are more likely to be involved in the regulation of the developmental gene SHOX than in the more abundantly expressed Ser/Thr phosphatase PPP2R3B.

Deletions downstream (3′) of SHOX have frequently been reported to occur in LWD patients and thus are of diagnostic relevance; however, no upstream (5′) deletions have been reported so far. Using FISH and SNP analysis, we screened a cohort of 60 LWD patients with an intact SHOX-coding region for deletions upstream of the SHOX gene, but could not find any deletion that exclusively affected this interval. Here, we offer two possible explanations for the differing frequency of deletions found in the downstream region compared with the upstream region.

First, the considerably higher repeat content of the downstream region compared with that of the upstream region could lead to an increased deletion frequency in this area (Table 1). Alu and LINE elements are architectural features that lead to a higher susceptibility to genomic rearrangements and therefore could be involved in the occurrence of the observed deletions.22 Furthermore, the relatively low GC content of the downstream region could argue for an increased deletion frequency, as AT-rich sequences are more likely to denature and form secondary structures because of their decreased melting temperatures. Similarly, it is known that especially AT-rich palindromic sequences can lead to genomic rearrangements by forming hairpin structures or by generating double-strand breaks.23

Second, symptoms in patients with upstream deletions may differ from the symptoms observed in LWD. Thus, these patients might not have been diagnosed for LWD and therefore were not part of the LWD cohort screened. As described for other disorders, the symptoms observed in patients with disruptions of the regulatory regions of a gene can sometimes differ from the symptoms caused by deletions of the gene itself.18 As the upstream enhancers of SHOX are active in the limb bud (but not in the cornea), a deletion of these enhancers may cause a limb phenotype. However, this limb phenotype possibly differs from the one observed for deletions of the SHOX coding region or of the SHOX downstream region, as the regulatory region upstream of SHOX may control slightly different expression domains in the limb bud. Indeed, the skeletal anomalies seen in the patient described by Bleyl et al,16 in whom the SHOX upstream region is translocated away and therefore separated from the SHOX gene, overlap with but are more severe and partly distinct from those seen in LWD. The patient's distal limbs are notably short and radiographs showed a shortened bowed radius and a short thickened ulna, consistent with the symptoms typically seen in LWD. Presumably, the translocation of enhancers leads to a reduction in SHOX expression, resulting in some typical LWD symptoms. In addition, the patient has talipes equinovarus (club feet) and the lower limbs show decreased muscle mass, both symptoms not normally associated with LWD. Possibly, one or more of the upstream enhancers are responsible for the accurate expression in the respective region of the developing limb so that the loss of these enhancers might lead to these additional symptoms. It also cannot be excluded that the translocated region contains silencer elements in addition to the identified enhancer elements that cannot be functionally identified by our in ovo enhancer assay. A lack of these silencers could evoke ectopic SHOX expression, thus providing another possible explanation for the additional symptoms observed in the patient. In the patient described by Bleyl et al,16 misexpression of SHOX may also be a consequence of a gain of enhancer elements translocated from Xq during the inversion event.

Despite the fact that SHOX expression is found in the eye, the patient's additional eye phenotype (Peters Anomaly) is not likely to be caused by the translocation of SHOX enhancers, as none of the upstream CNEs showed any activity in the chicken enhancer assay in the eye. These symptoms may be explained by the second break point (near SOX3) of the X-chromosome inversion.16

Taken together, we have shown that not only the region downstream of SHOX contains active limb enhancers7, 10, 11, 12 but also the region upstream of the gene. We also provide an explanation for the discrepancy between the number of deletions up- and downstream of the SHOX gene found in LWD patients. Owing to the structural differences of the two regions, the total number of upstream deletions is presumably lower; however, it seems likely that deletions exist, yet they might lead to a phenotype that is typically not diagnosed as LWD and therefore excluded from current screening studies. We therefore suggest that the upstream enhancer region of SHOX should be considered in severe skeletal dysplasia with mesomelic shortening of upper and lower limbs.

Acknowledgments

C Durand is funded by a fellowship from Landesgraduiertenförderung Baden-Württemberg. We thank Ralph Roeth for technical assistance and valuable support and Katja Schneider for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Belin V, Cusin V, Viot G, et al. SHOX mutations in dyschondrosteosis (Leri-Weill syndrome) Nat Genet. 1998;19:67–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shears DJ, Vassal HJ, Goodman FR, et al. Mutation and deletion of the pseudoautosomal gene SHOX cause Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. Nat Genet. 1998;19:70–73. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao E, Weiss B, Fukami M, et al. Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:54–63. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller S, Spranger S, Schechinger B, et al. Phenotypic variation and genetic heterogeneity in Leri-Weill syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:54–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier-Daire V, Huber C, Munnich A. Allelic and nonallelic heterogeneity in dyschondrosteosis (Leri-Weill syndrome) Am J Med Genet. 2001;106:272–274. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement-Jones M, Schiller S, Rao E, et al. The short stature homeobox gene SHOX is involved in skeletal abnormalities in Turner syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:695–702. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C, Rosilio M, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. High incidence of SHOX anomalies in individuals with short stature. J Med Genet. 2006;43:735–739. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.040998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappold G, Blum WF, Shavrikova EP, et al. Genotypes and phenotypes in children with short stature: clinical indicators of SHOX haploinsufficiency. J Med Genet. 2007;44:306–313. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.046581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wildhardt G, Zhong Z, et al. Enhancer mutations of the SHOX gene as a frequent cause of short stature – the essential role of a 250 kb downstream regulatory domain. J Med Genet. 2009;46:834–839. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabherwal N, Bangs F, Roth R, et al. Long-range conserved non-coding SHOX sequences regulate expression in developing chicken limb and are associated with short stature phenotypes in human patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:210–222. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito-Sanz S, Thomas NS, Huber C, et al. A novel class of Pseudoautosomal region 1 deletions downstream of SHOX is associated with Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:533–544. doi: 10.1086/449313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami M, Kato F, Tajima T, Yokoya S, Ogata T. Transactivation function of an approximately 800-bp evolutionarily conserved sequence at the SHOX 3′ region: implication for the downstream enhancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:167–170. doi: 10.1086/499254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer J, Johnson J, Niswander L. The use of in ovo electroporation for the rapid analysis of neural-specific murine enhancers. Genesis. 2001;29:123–132. doi: 10.1002/gene.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belo JA, Bouwmeester T, Leyns L, et al. Cerberus-like is a secreted factor with neutralizing activity expressed in the anterior primitive endoderm of the mouse gastrula. Mech Dev. 1997;68:45–57. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiecke E, Bangs F, Blaschke R, Farrell ER, Rappold G, Tickle C. Expression of the short stature homeobox gene Shox is restricted by proximal and distal signals in chick limb buds and affects the length of skeletal elements. Dev Biol. 2006;298:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyl SB, Byrne JL, South ST, et al. Brachymesomelic dysplasia with Peters anomaly of the eye results from disruptions of the X chromosome near the SHOX and SOX3 genes. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2785–2795. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjan DA, van Heyningen V. Long-range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:8–32. doi: 10.1086/426833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettice LA, Hill RE. Preaxial polydactyly: a model for defective long-range regulation in congenital abnormalities. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammandel B, Chowdhury K, Stoykova A, Aparicio S, Brenner S, Gruss P. Distinct cis-essential modules direct the time-space pattern of the Pax6 gene activity. Dev Biol. 1999;205:79–97. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin C, Kleinjan DA, Doe B, van Heyningen V. New 3′ elements control Pax6 expression in the developing pretectum, neural retina and olfactory region. Mech Dev. 2002;112:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benko S, Fantes JA, Amiel J, et al. Highly conserved non-coding elements on either side of SOX9 associated with Pierre Robin sequence. Nat Genet. 2009;41:359–364. doi: 10.1038/ng.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CJ, Lupski JR. Implications of human genome architecture for rearrangement-based disorders: the genomic basis of disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13 (Spec No 1:R57–R64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann L, Spiteri E, Koren K, et al. AT-rich palindromes mediate the constitutional t(11;22) translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1–13. doi: 10.1086/316952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.