Abstract

The 6p21-p22 chromosomal region has been identified as a developmental dyslexia locus both in linkage and association studies, the latter generating evidence for the doublecortin domain containing 2 (DCDC2) as a candidate gene at this locus (and also for KIAA0319). Here, we report an association between DCDC2 and reading and spelling ability in 522 families of adolescent twins unselected for reading impairment. Family-based association was conducted on 21 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in DCDC2 using quantitative measures of lexical processing (irregular-word reading), phonological decoding (non-word reading) and spelling-based measures of dyslexia derived from the Components of Reading Examination test. Significant support for association was found for rs1419228 with regular-word reading and spelling (P=0.002) as well as irregular-word reading (P=0.004), whereas rs1091047 was significantly associated (P=0.003) with irregular-word reading (a measure of lexical storage). Four additional SNPs (rs9467075, rs9467076, rs7765678 and rs6922023) were nominally associated with reading and spelling. This study provides support for DCDC2 as a risk gene for reading disorder, and suggests that this risk factor acts on normally varying reading skill in the general population.

Keywords: dyslexia, DCDC2, reading ability, spelling ability

Introduction

Dyslexia is a common neurobehavioral disorder of reading1 and likely represents the low tail of a reading ability distribution in the population.2, 3 Linkage analyses have identified at least 11 distinct chromosomal regions4, 5 contributing to the disorder, and one of the earliest reported linkages for reading, 6p21-p22,6 has yielded two of the candidate genes: KIAA03197 and doublecortin domain containing 2 (DCDC2).8

Support for DCDC2 as a candidate dyslexia gene was first reported by Deffenbacher et al8 in a linkage and association study of the chromosome 6p21.3 quantitative trait loci (QTL) in 349 families collected through the Colorado Learning Disabilities Center (CLDRC). Linkage was observed in a subsample of families selected for severity, suggesting that the QTL was specific for severe reading disability rather than normal reading variation. Deffenbacher et al found evidence of association between measures of reading ability for 13 of 31 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) tested, eight of which were located within DCDC2. Two intronic SNPs (rs793862 and rs870601) were associated with three of five reading phenotypes examined, including orthographic coding (the ability to read aloud irregular words), phonological decoding (the ability to read aloud non-words) and overall reading ability. Following this study, Meng et al9 typed 147 SNPs, including 32 DCDC2 SNPs, spanning chromosome 6p22 in a subset of 153 CLDRC dyslexic families. The strongest associations reported were between two DCDC2 SNPs (rs807724 and rs1087266) and overall reading ability, with eight additional SNPs (including rs793862) reaching nominal significant levels of association. Schumacher et al10 also found evidence of association between multiple DCDC2 SNPs and dyslexia in two independent German samples using transmission disequilibrium, with the strongest evidence for association at SNPs rs793862 and rs807701 in individuals with severely affected spelling ability. By contrast, three studies7, 11, 12 have failed to replicate associations reported by Meng et al and Schumacher et al in samples of affected families recruited in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada.

A candidate mechanism for a functional effect of DCDC2 on dyslexia is indicated by the finding that downregulation of DCDC2 disrupts neuronal migration,9 a process hypothesized to have a role in dyslexia13 and consistent with function in other members of the DCX family, where mutations in DCX, the doublecortin gene, have an established effect on neuron migration.14 Interestingly, a 2455-bp deletion identified by Meng et al9 and located between the exons encoding the two doublecortin domains contained a simple tandem repeat (STR) with putative brain-related transcription factor binding sites. The authors concluded that loss of these transcription sites could affect DCDC2 function. Although this deletion in conjunction with the STR was significantly associated with reading performance in US families,9 the association was either weak or absent in United Kingdom and German cohorts.7, 15 However, a recent voxel-based morphometry study16 showed a positive correlation between the deletion and variation in gray matter volume in brain regions previously associated with language.

At the level of association, then, support for DCDC2 as a candidate dyslexia gene is mixed, and the strength and phenotypic target of the association requires clarification. We therefore tested for association between 21 SNPs spanning DCDC2 and a battery of reading and spelling component processes plus a principal component factor score derived from the Components of Reading Examination (CORE)17 in a sample of adolescent twins and their families (N=1067) unselected for reading impairment. Evidence of association in our study would provide further support for this gene as a dyslexia candidate, and extend its potential role into the realm of normal variation in reading and spelling.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twins were initially recruited into ongoing studies of melanoma risk factors18 and cognition.19 Data were also gathered from non-twin siblings, with families comprising up to four non-twin siblings. The sample was 98% Caucasian and predominantly of Anglo-Celtic (82%) descent and representative of the Queensland population for intellectual ability.20 Blood samples for DNA extraction were obtained from twins, non-twin siblings and 85.1% of parents. Zygosity was assessed using nine polymorphic DNA microsatellite markers (AmpF1STR Profiler Plus Amplification Kit, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and three blood groups (ABO, MNS and Rh), giving a probability of correct assignment >99.99%.21 Ethics approval for this study was received from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research. Before administration of the reading, spelling and cognition tests and blood collection, written informed consent was obtained and for those under 18 years, consent was also obtained from their parent/guardian.

Measures and procedure

Reading, spelling and cognition phenotypes were available for 1067 participants (48.8% males) from 522 families comprising 90 monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs (57 female and 33 male), 305 dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs (80 female, 75 male and 150 opposite sex), 117 unpaired twins and 160 non-twin siblings. Participants ranged in age from 12 to 25 years (mean age was 17.7±2.8 years for twins; 18.4±2.6 years for siblings).

Regular-word, irregular-word and non-word readings were assessed using CORE,17 a 120-word extended version of the Castles and Coltheart22 test with additional items added to increase the difficulty of this test for an older sample and to extend the test into the domain of spelling. Measures were administered over the telephone by trained researchers with written materials delivered in separate sealed envelopes, opened in the audible presence of the tester, and read aloud. If the envelope had been opened before testing, the subject was excluded from the study. Inter-rater reliability of scoring (based on rescoring of a subset by the last author from the digital recordings) was near 100%. Test–retest reliability for a subset of 60 subjects was also high, and the reading scores have been validated in previous behavior genetic23 and linkage4 papers. Regular and irregular-word spelling were tested using 18 regular words and 18 irregular words, respectively, from the CORE. These were presented verbally, untimed and in mixed order, the dependent variable being the number of words spelled correctly to oral challenge. Non-lexical spelling was assessed by having subjects produce a regularized spelling for each of the 18 words given in the irregular spelling test. Words were repeated on request. For a full description of the test protocols and the list of words used, see Bates et al.17 Test scores on each of the three reading and three spelling subtests were calculated as a simple sum of correct items (see Table 1 for means and SDs). Before analysis, all raw data were log-odds transformed to approximate normality. A previous multivariate linkage study of six reading and spelling phenotypes showed that each measure contributed to the linkage at 6p.24 Therefore, we derived a principal component factor score (CORE-PC) from our measures. The CORE-PC explained 66.3% of the variance and loadings on each of six reading and spelling subtests are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Six measures of reading and spelling derived from the Components of Reading Examination test.

| Task | Mean (% correct) | Standard deviation | Range (% correct) | CORE-PC loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading | ||||

| Irregular words | 80.0 | 11.8 | 33–100 | 0.855 |

| Regular words | 93.8 | 7.2 | 43–100 | 0.808 |

| Non-words | 76.8 | 18.0 | 0–100 | 0.845 |

| Spelling | ||||

| Irregular words | 55.3 | 21.3 | 0–100 | 0.870 |

| Regular words | 84.9 | 14.5 | 11–100 | 0.811 |

| Non-words | 50.7 | 19.7 | 0–94 | 0.682 |

CORE-PC, principal component factor score derived from the Components of Reading Examination test.

IQ was assessed using the brief Multi-dimensional Aptitude Battery comprising three verbal (information, vocabulary, arithmetic) and two performance (spatial, object assembly) subtests.25 Scaled scores for overall intelligence quotient (full-scale IQ) as well as measures of verbal IQ and performance IQ (PIQ) were compiled following manual instructions and were normally distributed. Intelligence was used as a covariate in all analyses as general cognitive ability has been shown to increase sensitivity for reading ability.26 Performance IQ rather than verbal ability was used as the covariate to avoid confounds with reading ability.

Genotyping

Twenty-nine SNPs across the 211.5-kb DCDC2 locus were selected on the basis of available data: 12 SNPs from DCDC2 association studies;8, 9, 10 and 17 haplotype-tagging SNPs chosen from the International HapMap Project public database (Phase II dbSNP Build 124)27 using Haploview28 software (version 3.2) for complete coverage of DCDC2. Assays were designed using MassARRAY Assay Design (version 3.0) software (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and typed using iPLEX chemistry on a Compact MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometer (Sequenom Inc.). Forward and reverse PCR primers and primer extension probes were purchased from Bioneer Corporation (Daejeon, Korea). Genotyping was carried out in standard 384-well plates with 12.5 ng genomic DNA used per sample. Allele calls were reviewed using the cluster tool in the SpectroTyper software (Sequenom Inc.) to evaluate assay quality. Genotype error checking, sample identity and zygosity assessment and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium analyses were completed in PEDSTATS29 and Merlin.30 Eight SNPs failed during the assay design or provided unreliable genotype data and were excluded from further analysis. The 2455-bp deletion and STR in intron 2 were not genotyped because they required specific typing that was not available.

Statistical analyses

Tests of total association with each of the reading and spelling subtests and the CORE-PC score were conducted in the program QTDT.31 Total association considers transmission within and between families, specifying an additive model against the null hypothesis of no linkage and no association. Standardized residuals of the seven measures were adjusted for sex, age, interviewer and PIQ effects before submission to QTDT. MZ twins are modeled as such by adding zygosity status to the data file. The between-family association component is not robust to population admixture, whereas the within-family component is unaffected by spurious associations because of population structure. Thus, if population structure creates a false association, the test for association using the within-family component is still valid, though usually less powerful. Therefore, additional analyses were performed in QTDT to check for population stratification by: (1) using a variant of the orthogonal model, which evaluates population stratification by comparing the between- and within-family components of association (Supplementary Table S1) and (2) restricting analysis to individuals who reported at least 75% Anglo-Celtic ancestry (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, allelic odds ratios (ORs) and 95% Wald confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated by dividing the data set into unrelated individuals with above average reading ability (CORE-PC scores >1 SD from the covariate corrected mean) and below average reading ability (<1 SD from the covariate corrected mean). Allelic frequency differences between the two groups were analyzed in Haploview (version 3.31)28 and empirical P-values were determined by running 1000 permutations.

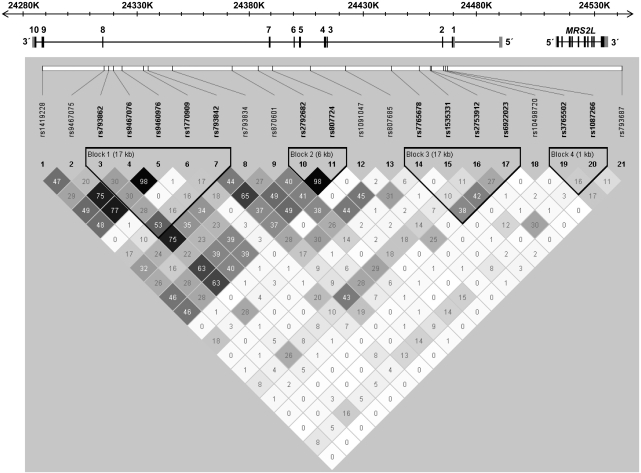

Inter-marker linkage disequilibrium (LD) was assessed in Haploview (version 3.31).28 Reflecting moderate LD across DCDC2 (Figure 1), many SNPs were correlated, and as a result the effective number of statistical tests done was substantially less than the actual number of tests. The effective number of independent SNPs was 14.03, as determined by SNPSpD.32 In addition, principal component factor analysis indicates that the six reading and spelling subtests accounted for one independent phenotypic factor. Therefore, a P-value <0.0036 (0.05/14) is required for study-wide significance. We have ∼90% power (α=0.05) to detect overall association with an SNP with minor allele frequency above 0.05, which explains 1% of variance in our trait under an additive model and against a background sibling correlation of 0.30.33

Figure 1.

The location of SNPs genotyped across the 253-kb region spanning DCDC2. The gene structure of DCDC2 is shown with exons numbered from 1 to 10, and the relative exon size is denoted by the width of the vertical bars. Gray bars denote untranslated regions. The structure of MRS2L is also represented. Pairwise marker–marker linkage disequilibrium (LD; shown below the gene structure) and LD blocks were generated using Haploview 3.31.28 Regions of low-to-high LD, as measured by the r2 statistic, are represented by light gray to black shading, respectively. LD blocks were analyzed using an algorithm by Gabriel et al.34

Results

Descriptive

The means and SDs of the raw scores for each of the reading and spelling subtests from the CORE battery are given in Table 1. Twenty-one SNPs spanning DCDC2 were genotyped in 3834 individuals comprising the 1067 phenotyped participants plus 925 twins, 324 siblings and 1518 parents without reading, spelling and cognition phenotypes available. Genotype frequencies for all SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Mendelian inconsistencies made up 0.09% of the data; a further 0.56% of the data were probable genotyping errors and removed from analysis. The physical locations of and inter-marker LD between the 21 SNPs are schematically presented in Figure 1. Four haplotype blocks spanning small clusters of SNPs were observed in our sample according to the criteria of Gabriel et al.34 Although the major haplotype block detected contained 6 SNPs spanning intron 7 to exon 8, the other blocks were detected in intron 1, intron 2 and a region spanning intron 6 to intron 7. This is consistent with LD data from the HapMap database27 for CEPH families of European origin (Supplementary Figure S1).

Single SNP association analyses

SNP marker information and total association results for the CORE-PC factor score and the six reading and spelling measures are given in Table 2. Evidence of population stratification (P<0.05) was observed between rs807685 and non-word spelling, rs2753912 and non-word reading and spelling, and between rs10498720 and regular-word spelling (Supplementary Table S1). Tests of within-family association, which is robust to population stratification, at these SNPs and phenotypes were nominally significant (P≈0.02) for rs10498720 and rs807685 and non-word spelling and for rs10498720 and regular-word spelling (Supplementary Table S3). The strongest evidence of association with the CORE-PC measure of general reading ability was observed with rs1419228 in intron 9 (P=0.0016), where the minor C-allele related to poorer general reading performance with a (covariate-corrected) mean effect of 0.177 SD, that is, explaining 0.87% of variance in the CORE-PC score (Table 2). Another intronic SNP (rs1091047) was significantly associated with general reading ability with the major G-allele conferring a general reading disadvantage of 0.151 SD. In addition, unrelated participants with a below average reading ability (N=126), as defined by scores <1 SD from the mean CORE-PC score, were 2.2-fold more likely to carry the rs1091047 G-allele (OR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.31–3.54, P=0.002, empirical P=0.04) than individuals scoring >1 SD from the mean (N=134).

Table 2. DCDC2 gene marker information and total association results for the standardized principal component factor score (CORE-PC) derived from the Components of Reading Examination (CORE) test, plus the six CORE reading and spelling measures.

| Alleles | Reading (P-values) | Spelling (P-values) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | SNP IDa | Chromosomal location (bp)b | Gene position | Minorg | Major | MAFc | CORE-PC (P-value) | Risk alleled | Effect sizee (SD) | Variancef (%) | Irreg | Reg | NW | Irreg | Reg | NW |

| rs1419228 | D4, M20, S | 24 286 285 | Intron 9 | C | T | 0.167 | 0.0016 | C | 0.177 | 0.87 | 0.0038 | 0.0018 | 0.034 | 0.039 | 0.0021 | 0.12 |

| rs9467075 | 24 313 215 | Exon 8 | T | C | 0.124 | 0.036 | T | 0.127 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.038 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.045 | 0.59 | |

| rs793862 | D6, M26, S | 24 315 179 | Intron 7 | T | C | 0.265 | 0.70 | T | 0.018 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.35 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 0.25 |

| rs9467076 | S | 24 317 234 | Intron 7 | G | A | 0.101 | 0.035 | G | 0.136 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.028 | 0.42 |

| rs9460976 | S | 24 321 099 | Intron 7 | T | C | 0.102 | 0.11 | T | 0.103 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| rs1770909 | 24 330 431 | Intron 7 | T | C | 0.115 | 0.79 | T | 0.018 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.91 | 0.84 | |

| rs793842 | M27 | 24 332 467 | Intron 7 | A | G | 0.405 | 0.80 | G | 0.011 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 0.43 |

| rs793834 | S | 24 342 912 | Intron 7 | T | C | 0.244 | 0.16 | T | 0.068 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.67 |

| rs870601 | D7 | 24 369 039 | Intron 7 | A | G | 0.324 | 0.88 | A | 0.007 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| rs2792682 | 24 380 363 | Intron 7 | G | T | 0.222 | 0.68 | G | 0.021 | 0.02 | 0.90 | 0.49 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 0.41 | |

| rs807724 | D8, M33 | 24 386 848 | Intron 6 | G | A | 0.219 | 0.45 | G | 0.037 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.12 | 0.51 |

| rs1091047 | 24 403 235 | Intron 4 | C | G | 0.169 | 0.0076 | G | 0.151 | 0.64 | 0.0034 | 0.0083 | 0.022 | 0.045 | 0.20 | 0.27 | |

| rs807685 | D10, S | 24 418 623 | Intron 2 | T | A | 0.123 | 0.31 | T | 0.064 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.87 | 0.08 | 0.59 |

| rs7765678 | 24 438 523 | Intron 2 | G | A | 0.083 | 0.044 | A | 0.172 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.0099 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.41 | |

| rs1535331 | S | 24 450 591 | Intron 2 | C | T | 0.090 | 0.20 | T | 0.101 | 0.17 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.50 |

| rs2753912 | M45 | 24 455 603 | Intron 2 | T | C | 0.456 | 0.50 | T | 0.029 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.54 |

| rs6922023 | M46 | 24 456 096 | Intron 2 | A | G | 0.187 | 0.046 | G | 0.115 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.047 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.57 |

| rs10498720 | 24 461 415 | Intron 2 | C | A | 0.042 | 0.64 | A | 0.052 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.19 | 0.72 | |

| rs3765502 | 24 462 024 | Intron 1 | C | T | 0.120 | 0.92 | T | 0.007 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.80 | 0.82 | |

| rs1087266 | D12, M49 | 24 463 129 | Intron 1 | A | G | 0.458 | 0.23 | A | 0.051 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.69 |

| rs793687 | D15, M72 | 24 539 037 | Intron 20h | G | T | 0.340 | 0.31 | T | 0.045 | 0.09 | 0.84 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.30 |

bp, base-pair; CORE-PC, principal component factor score derived from the Components of Reading Examination test; Irreg, irregular word; MAF, minor allele frequency; NW, non-word; Reg, regular word; SD, standard deviation; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Bold P-values indicate P-value <0.05 (P-values are uncorrected for multiple testing). A total of 1067 phenotyped twins and siblings from 522 families were included in the analyses.

Indicates whether the SNP has been previously genotyped by Deffenbacher et al8 (the equivalent number of the reported SNP is assigned as ‘D#'), Meng et al9 (the equivalent number of the reported SNP is assigned as ‘M#') or Schumacher et al10 (listed as ‘S').

Base-pair position on NCBI Genome Build 130.

Minor allele frequency in the parents of our twin sample.

Allele that confers a lower CORE-PC factor score for each SNP.

Effect size of the at-risk allele in standard deviations from the mean CORE-PC score.

Percentage of the CORE-PC score variance explained by the SNP.

Allele with the lowest frequency.

Location in the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase D1 gene (GPLD1).

Secondary analyses of the CORE reading and spelling subtests indicated that rs1419228 was also significantly associated with the ability to read and spell regular-words as well as irregular-word reading, whereas rs1091047 was significantly associated with irregular-word reading. Four other SNPs were nominally associated with the CORE-PC score and one or more of the reading and spelling subtests. However, given the effective number of independent tests (∼14, giving a threshold level of significance of 0.0036), only the CORE-PC and regular-word reading and spelling results for rs1419228 and the irregular-word reading finding with rs1091047 remain significant after correcting for multiple testing. Additional analyses restricted to 895 individuals from 441 families who reported at least 75% Anglo-Celtic ancestry resulted in minor changes to the overall results (eg, the association between rs1419228 and the CORE-PC score was reduced from 0.0016 to 0.014), consistent with the lower power of the smaller sample (Supplementary Table S3). As DCDC2 and another candidate dyslexia gene, KIAA0319, are in close proximity (∼200 kb apart), long-range LD between rs1419228 and rs1091047 and variants in surrounding genes (KIAA0319, VMP, THEM2, TTRAP) was investigated in ssSNPer.35 In each analysis, low levels of LD (r2<0.35) were observed beyond the DCDC2 locus, suggesting that the reported association signals were located within DCDC2.

Discussion

We tested for association between 21 SNPs spanning DCDC2 and seven reading and spelling measures, including a general reading ability factor, in a large sample of adolescent and young adult twins and siblings, representative of the general population for reading and spelling ability. After correcting for multiple testing, rs1419228 remained significantly associated with the CORE-PC factor score, with the C-allele conferring a general reading and spelling disadvantage of 0.177 SD. This result is supported by the independent report of a haplotypic association with irregular-word reading (orthographic coding) and an overall measure of reading ability8 in CLDRC dyslexic families stratified for severity where a haplotype spanning VMP/DCDC2 that carried the rs1419228 C-allele was over-transmitted to affected probands. Two subsequent studies10, 12 did not find evidence for association between rs1419228 and dyslexia in German and Canadian samples, respectively. There are distinguishing factors that may explain these differences – German, of course, places distinct demands on the reading system compared with English, and phenotypes have differed between studies, but more research is required to understand the role of rs1419228 in reading and the location of the disease mutation. Interactions with population-specific background genetics may be relevant.

In addition to rs1419228, the G-allele of intronic SNP rs1091047 was significantly associated with orthographic coding and with the broader CORE-PC phenotype. This polymorphism has not been previously studied, and, as it is not in LD (r2≈0) with rs1419228 or indeed with SNPs in neighboring genes (r2<0.35), it represents a potential novel risk allele. Replication of this SNP, along with expression and/or sequencing analyses to uncover its associated functional effects, would be desirable. We did not find significant support for association of reading and spelling with rs793862, the most widely genotyped polymorphism in DCDC2 association studies; though we did observe the same at-risk allele as in earlier studies10, 11, 36, 37 (the T-allele conferred a reading disadvantage of just 0.02 SD). Contradictory findings have been reported for this SNP: from nominally significant associations,8, 9 to associations specific only in the most severely affected families,10 to the reverse effect (a nominally significant association in independent UK samples that disappeared when the sample was restricted to individuals with severe spelling difficulties7), to no support for association of rs793862 to dyslexia in a cohort of US families.11 On balance then, evidence for rs793862 is mixed, perhaps favoring an association with severe disorder only at best.

The strong association between rs1419228 and the CORE-PC measure of common variance across the six components of reading and spelling indicates that the causative gene in this region affects biological processes common to both major forms of dyslexia, rather than being restricted to one subtype of dyslexia.3 This conclusion is further supported by the series of phenotypes previously studied8, 9, 10, 11 and recent findings that both shared and separate genetic factors influence the non-lexical and lexical routes of reading,3 as well as multivariate molecular evidence that converge on the notion that genes on 6p influence both orthographic and phonological decoding38 and that the QTL affects multiple reading-related measures.39

The mechanism of DCDC2's involvement in reading remains unclear. However, several lines of evidence,40, 41 including a recent study that investigated the effects of knocking down DCDC2,42 suggest a plausible role for DCDC2 in neuronal migration, which is postulated as a basic mechanism in dyslexia and related to the function of other genes associated with reading,13, 43 including the nearby gene KIAA0319.44 We have previously reported an association of KIAA0319 with reading, which was made when only 80.1% of this sample had been phenotyped (855 of the twins and their non-twin siblings).26 These observed associations for both DCDC2 and KIAA0319, together with their shared roles in neuronal migration, suggest that both genes may have a role in dyslexia. As yet, the biological mechanism relating DCDC2 to reading is unknown. Neither rs1419228 nor rs1091047 is a coding variant (although rs9467075 in exon 8 showed a trend toward association with general reading ability). As rs1419228 and rs1091047 are not in significant LD with SNPs typed in intron 2, it seems unlikely that they are related to the ungenotyped 2455 bp deletion located in intron 2, and their location relative to the 5′ end of exon 9 does not support a role in alternative splicing.10

Finally, the results of this study have important implications for the study of reading disability. Our results show that this association is present with a comparable effect size to that found in severely affected clinical samples, in normally varying participants. This further supports the hypothesis that dyslexia represents the low tail of a continuous distribution of reading ability.2 The implication is that the same genes influence poor and exceptional reading ability, and that genetic studies can maximize power by retaining this normal variation through the use of quantitative scores, as we have done.

Acknowledgments

We thank the twins and their parents for their cooperation; Anjali Henders and Megan Campbell for managing sample processing and DNA extraction; Alison Mackenzie and Thanuja Gunasekera for coordinating the reading test battery mail-out; and the many research interviewers for data collection. This research was supported by the Scottish Chief Scientists Office (TCB) and the Australian Research Council (#: A79600334, A79906588, A79801419, DP0212016 and DP0343921). ML was supported by an Australian Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship (grant # DP0449598).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Dyslexia (specific reading disability) Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz SE, Escobar MD, Shaywitz BA, Fletcher JM, Makuch R. Evidence that dyslexia may represent the lower tail of a normal distribution of reading ability. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:145–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201163260301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates TC, Castles A, Luciano M, Wright MJ, Coltheart M, Martin NG. Genetic and environmental bases of reading and spelling: a unified genetic dual route model. Read Writ. 2007;20:147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bates TC, Luciano M, Castles A, Coltheart M, Wright MJ, Martin NG. Replication of reported linkages for dyslexia and spelling and suggestive evidence for novel regions on chromosomes 4 and 17. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:194–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, O'Donovan MC. The genetics of developmental dyslexia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:681–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardon LR, Smith SD, Fulker DW, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF, DeFries JC. Quantitative trait locus for reading disability on chromosome 6. Science. 1994;266:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.7939663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold D, Paracchini S, Scerri T, et al. Further evidence that the KIAA0319 gene confers susceptibility to developmental dyslexia Mol Psychiatry 2006111085–1091.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher KE, Kenyon JB, Hoover DM, et al. Refinement of the 6p21.3 quantitative trait locus influencing dyslexia: linkage and association analyses. Hum Genet. 2004;115:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Smith SD, Hager K, et al. DCDC2 is associated with reading disability and modulates neuronal development in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17053–17058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508591102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J, Anthoni H, Dahdouh F, et al. Strong genetic evidence of DCDC2 as a susceptibility gene for dyslexia. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:52–62. doi: 10.1086/498992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brkanac Z, Chapman NH, Matsushita MM, et al. Evaluation of candidate genes for DYX1 and DYX2 in families with dyslexia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:556–560. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto JM, Livne-Bar I, Huang K, et al. Association of reading disabilities with regions marked by acetylated H3 histones in KIAA0319 Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2009. e-pub ahead of print 8 July 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Galaburda AM, Sherman GF, Rosen GD, Aboitiz F, Geschwind N. Developmental dyslexia: four consecutive patients with cortical anomalies. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:222–233. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Lin PT, Flanagan LA, Walsh CA. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:257–271. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig KU, Schumacher J, Schulte-Korne G, et al. Investigation of the DCDC2 intron 2 deletion/compound short tandem repeat polymorphism in a large German dyslexia sample. Psychiatr Genet. 2008;18:310–312. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283063a78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Gelernter J, Gruen JR, et al. Polymorphism of DCDC2 reveals differences in cortical morphology of healthy individuals-a preliminary voxel based morphometry study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2008;2:21–26. doi: 10.1007/s11682-007-9012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates TC, Castles A, Coltheart M, Gillespie N, Wright MJ, Martin NG. Behaviour genetic analyses of reading and spelling: a component processes approach. Aust J Psychol. 2004;56:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Duffy DL, Eldridge A, et al. A major quantitative-trait locus for mole density is linked to the familial melanoma gene CDKN2A: a maximum-likelihood combined linkage and association analysis in twins and their sibs. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:483–492. doi: 10.1086/302494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MJ, Martin NG. Brisbane Adolescent Twin Study: outline of study methods and research projects. Aust J Psychol. 2004;56:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Wright MJ, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, Smith GA, Martin NG. A genetic investigation of the covariation among inspection time, choice reaction time, and IQ subtest scores. Behav Genet. 2004;34:41–50. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000009475.35287.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholt DR. On the probability of dizygotic twins being concordant for two alleles at multiple polymorphic loci. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:194–197. doi: 10.1375/183242706776382383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castles A, Coltheart M. Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition. 1993;47:149–180. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(93)90003-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NW, Hansell NK, Wainwright MA, et al. Genetic covariation between the Author Recognition Test and reading and verbal abilities: what can we learn from the analysis of high performance. Behav Genet. 2009;39:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9275-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow AJ, Fisher SE, Richardson AJ, et al. Investigation of quantitative measures related to reading disability in a large sample of sib-pairs from the UK. Behav Genet. 2001;31:219–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1010209629021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN. Manual for the Multidimensional Aptitude Battery. Port Huron, MI: Research Psychologists Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Lind PA, Duffy DL, et al. A haplotype spanning KIAA0319 and TTRAP is associated with normal variation in reading and spelling ability. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International HapMap Consortium The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton JE, Abecasis GR. PEDSTATS: descriptive statistics, graphics and quality assessment for gene mapping data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3445–3447. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin – rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Cookson WO. A general test of association for quantitative traits in nuclear families. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:279–292. doi: 10.1086/302698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholt DR. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:765–769. doi: 10.1086/383251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:149–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholt DR. ssSNPer: identifying statistically similar SNPs to aid interpretation of genetic association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2960–2961. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto JM, Gomez L, Wigg K, et al. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with a candidate region for reading disabilities on chromosome 6p. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcke A, Weissfuss J, Kirsten H, Wolfram G, Boltze J, Ahnert P. The role of gene DCDC2 in German dyslexics. Ann Dyslexia. 2009;59:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11881-008-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DE, Gayan J, Ahn J, et al. Evidence for linkage and association with reading disability on 6p21.3-22. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1287–1298. doi: 10.1086/340449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow AJ, Fisher SE, Francks C, et al. Use of multivariate linkage analysis for dissection of a complex cognitive trait. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:561–570. doi: 10.1086/368201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Allen KM, Fox JW, et al. Doublecortin, a brain-specific gene mutated in human X-linked lissencephaly and double cortex syndrome, encodes a putative signaling protein. Cell. 1998;92:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Bai J, Wang Y, et al. Disruption of neuronal migration by RNAi of Dyx1c1 results in neocortical and hippocampal malformations. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2562–2572. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbridge TJ, Wang Y, Volz AJ, et al. Postnatal analysis of the effect of embryonic knockdown and overexpression of candidate dyslexia susceptibility gene homolog Dcdc2 in the rat. Neuroscience. 2008;152:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM, LoTurco J, Ramus F, Fitch RH, Rosen GD. From genes to behavior in developmental dyslexia. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1213–1217. doi: 10.1038/nn1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paracchini S, Thomas A, Castro S, et al. The chromosome 6p22 haplotype associated with dyslexia reduces the expression of KIAA0319, a novel gene involved in neuronal migration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1659–1666. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.