Abstract

Serosorting, the practice of selectively engaging in unprotected sex with partners of the same HIV serostatus, has been proposed as a strategy for reducing HIV transmission risk among men who have sex with men (MSM). However, there is a paucity of scientific evidence regarding whether women engage in serosorting. We analyzed longitudinal data on women’s sexual behavior with male partners collected in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study from 2001 to 2005. Serosorting was defined as an increasing trend of unprotected anal or vaginal sex (UAVI) within seroconcordant partnerships over time, more frequent UAVI within seroconcordant partnerships compared to non-concordant partnerships, or having UAVI only with seroconcordant partners. Repeated measures Poisson regression models were used to examine the associations between serostatus partnerships and UAVI among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. The study sample consisted of 1,602 HIV-infected and 664 HIV-uninfected women. Over the follow-up period, the frequency of seroconcordant partnerships increased for HIV-uninfected women but the prevalence of UAVI within seroconcordant partnerships remained stable. UAVI was reported more frequently within HIV seroconcordant partnerships than among serodiscordant or unknown serostatus partnerships, regardless of the participant’s HIV status or types of partners. Among women with both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected partners, 41% (63 HIV-infected and 9 HIV-uninfected) were having UAVI only with seroconcordant partners. Our analyses suggest that serosorting is occurring among both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in this cohort.

Keywords: HIV, Unprotected sex, Serosorting, Risk reduction, Condom use

Introduction

The concept of serosorting was first described by Suerez et al. [1] and Suarez and Miller [2] as an HIV risk reduction strategy whereby individuals choose to engage in unprotected sex only with those whom they believe are of the same HIV serostatus. To date, most research addressing serosorting has been conducted among men who have sex with men (MSM). In these studies, the evidence of serosorting was inferred by: (1) an increasing rate of unprotected sexual intercourse with HIV seroconcordant partners over time [3-5]; (2) an elevated risk of unprotected sex among HIV seroconcordant versus serodiscordant or unknown sexual partnerships [6-8]; or (3) individuals reporting unprotected sex only with their seroconcordant partners, but not with other partners [9-11]. Other studies have examined serosorting directly by asking study participants whether they selectively had unprotected sex with partners of seroconcordant status [12-14].

Although the practice of serosorting has been used as an alternative for condom use, it is not risk-free. For example, the risk for HIV infection exists in sexual partnerships where the perceptions of the partner’s serostatus are inaccurate [11, 15, 16]. Since unprotected heterosexual intercourse accounts for 80% of new HIV diagnoses among women in the United States [17] and there is very little information available regarding the practice of serosorting among women, we examined the relationships between condom use practices and partner HIV serostatus among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The WIHS is a longstanding prospective cohort study of HIV/AIDS among women in the United States.

Methods

Study Design

The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) is a multi-center prospective cohort study that was established in 1994 to investigate the progression of HIV in women with or at risk for HIV. A total of 3,766 women (2,791 HIV-infected and 975 HIV-uninfected) were enrolled in either 1994–1995 (n = 2,623) or 2001–2002 (n = 1,143) from six United States cities [New York (Bronx and Brooklyn), Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington DC] [18]. Every 6 months, participants complete a comprehensive physical examination, provide blood specimens for CD4 cell count and HIV RNA determination, and complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire, which collects data on demographics, disease characteristics, and specific antiretroviral therapy use. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each site and written informed consent to participate in study activities was obtained from each participant.

For this study, we restricted our analysis to study visits between October 2001 and September 2005, when detailed questions were asked about each woman’s sexual behavior. All sexually active participants who completed at least two study visits during the observation period were included. The index visit was defined as the first visit observed in or after October 2001 for each participant.

Variable Definitions

At each study visit, every participant was asked detailed questions about sexual behavior with each of her 5 most recent male sexual partners in the past 6 months, including whether the partner was a husband, boyfriend or lover (characterized as a ‘main’ partner in our analysis). Other types of partners were codified as being ‘casual’ partners. We also assessed whether the partner was new (defined as a sexual relationship initiated since the last study visit). In addition, each woman was asked whether she had disclosed her HIV status to her partner and whether the partner had disclosed his HIV status (HIV-infected, HIV-uninfected, or unknown) to her. For this analysis, we categorized each partnership based on the woman’s HIV serostatus and the perceived HIV serostatus of her partner as seroconcordant, serodiscordant, or unknown serostatus. Unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse (UAVI) was defined as using condoms either ‘sometimes’ or ‘never’ (versus ‘always’). We examined the following as indicative of serosorting: (1) increasing trend of UAVI within seroconcordant partnerships over time [3-5]; (2) UAVI reported more frequently with partners of the same HIV status than with partners of a different or unknown HIV status (i.e., non-concordant HIV status) [6-8]; or (3) the observation that participants with sexual partners of different HIV status had UAVI only with their seroconcordant partners [9-11];

Demographic variables such as age, race/ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Latina/Hispanic and Other), educational achievement (less than high school, completed high school, and some college and above), and annual gross income (≤$12,000 vs. >$12,000 per year) were determined at the index visit. The following covariates were reported at each study visit and were dichotomized as ‘yes’ vs ‘no’: use of cocaine (including crack) or heroin (CCH), having a HIV-positive partner, having a new partner or having a casual partner since last study visit. The number of male sexual partners and consistency of condom use with all partners were also included. In order to ascertain perception of HIV risk in the HAART era, the women were also asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale to the following statement: “Because of combination drug treatments for HIV, I am less concerned about getting HIV or infecting someone else” [19, 20]. Responses were re-categorized as strongly agree/agree, uncertain and disagree/strongly disagree. At each study visit, total CD4+ T cells/mm3 were determined using standardized three or four color flow cytometry [21]. AIDS diagnosis was determined using the CDC 1993 criteria, and HAART was defined following the Department of Health and Human Service/Kaiser Panel guidelines [22].

Statistical Analyses

Central tendency statistics such as percentage and mean were used to describe participant characteristics. Since UAVI was not a rare event in this longitudinal study, estimated odds ratios from logistic regression might have been biased [23]. Thus, a repeated-measures Poisson regression model (generalized estimating equations method) was used. The probability of UAVI within seroconcordant partnerships was estimated and its trend was examined. Associations between serostatus partnership and UAVI with all partners were assessed separately for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. We further examined each model stratified by subgroups of partners such as main, casual or new partners. Adjusted prevalence ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were determined after taking into account within-individual correlations and adjusting for age, educational achievement, income, CCH use and perception of HIV risk in the HAART era. These covariates were selected based on their associations with sexual risk behavior established in previous studies [24, 25]. Statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05 in our analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

A total of 2,266 women (1,602 HIV-infected and 664 HIV-uninfected) met the selection criteria and contributed 11,931 person visits. Participants had a median follow-up of 2.5 years (interquartile range: 1.8–3.4 years) during this period. Characteristics of the study participants at the index visit by HIV status are shown in Table 1. Of these participants, about 57% were Black, 33% had some college education, 50% had annual income below $12,000 per year and 75% were still concerned about the risk of HIV transmission in the era of HAART. While HIV-uninfected participants were younger and less likely to report having had an HIV-infected partner, they reported higher numbers of male sexual partners, a larger percentage of casual or new partners, a higher level of inconsistent condom use, and more CCH use. Among the HIV-infected women at the index visit, 58% were using HAART, 38% had received an AIDS diagnosis and their median CD4+ T cell count was 447 cells/mm3.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics at study index visit

| Characteristics | HIV-uninfected women (N = 664) | HIV-infected women (N = 1602) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years): n(mean) | 664 (33.9) | 1602 (37.7) |

| Race/ethnicity: n(%) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 80 (12.0) | 192 (12.0) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 380 (57.2) | 918 (57.3) |

| Hispanic | 179 (27.0) | 433 (27.1) |

| Others | 25 (3.8) | 58 (3.6) |

| Education level: n(%) | ||

| Less than high school | 226 (34.4) | 619 (38.8) |

| High school | 209 (31.9) | 460 (28.8) |

| College and above | 221 (33.7) | 518 (32.4) |

| Income ≤$12,000 per year: n(%) | 322 (49.6) | 807 (51.3) |

| Number of male sexual partners (>1): n(%) | 237 (35.7) | 254 (15.9) |

| Having a HIV+ sexual partner: n(%) | 42 (6.7) | 442 (27.9) |

| Having a new partner: n(%) | 255 (38.4) | 413 (25.8) |

| Having a casual partner: n(%) | 243 (36.6) | 343 (21.4) |

| Consistent condom use: n(%) | 127 (19.1) | 877 (54.7) |

| Crack, cocaine and heroine use: n(%) | 121 (18.2) | 184 (11.5) |

| Because of combination drug treatments for HIV, I am less concerned about getting HIV or infecting someone else: n(%) | ||

| Agree | 116 (17.5) | 240 (15.0) |

| Uncertain | 58 (8.8) | 114 (7.1) |

| Disagree | 488 (73.7) | 1244 (77.9) |

| CD4+ T cell counts: n(median) | N/A | 1563 (447) |

| HAART use: n(%) | N/A | 936 (58.4) |

| AIDS diagnosis: n(%) | N/A | 606 (37.8) |

HIV human immunodeficiency virus, HAART highly active antiretroviral therapy, AIDS acquired immunodeficiency syndromes

Trends in HIV Status Communication, HIV Seroconcordance and UAVI

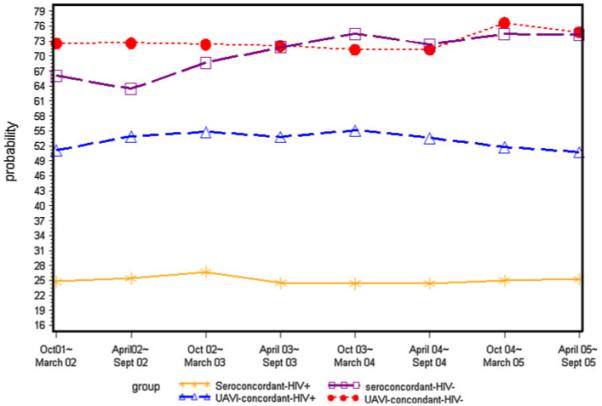

On average, 86% of women disclosed their HIV status to partners across study visits. However, only 76% of male partners disclosed their status. Communication of HIV status between women and their partners increased significantly over time. Furthermore, prevalence of seroconcordant partnership steadily increased (P < 0.01) for HIV-uninfected women, but remained stable (P = 0.62) for HIV-infected women (Fig. 1). In addition, the prevalence of UAVI within seroconcordant partnerships remained relatively stable over time for both HIV-infected (P = 0.51) and HIV-uninfected women (P = 0.20).

Fig. 1.

Trends in seroconcordant partnership and unprotected anal or vaginal sex within seroconcordant partnership among women with or at risk of HIV Infection, October 2001–September 2005

UAVI as a Function of HIV Seroconcordant Partnership

In the multivariate analyses, after adjusting for age, education, income, CCH use and perception of HIV risk in the HAART era, both HIV-infected (prevalence ratio (PR): 1.62; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.53-1.71) and HIV-uninfected (PR: 2.30; 95% CI: 1.86-2.85) women had substantially more UAVI with their seroconcordant partners than with partners of opposite HIV status (Table 2). Further analyses stratified by main, casual or new partners showed similar results, except that for HIV-uninfected women, no significant associations were observed between serostatus partnerships and UAVI with their new or casual partners. Since this lack of association was likely due to small number of serodiscordant partners, we repeated the analyses using non-concordant (discordant and unknown serostatus) partnership as reference group. We found similar results; for both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women and all types of partners, seroconcordant partnerships was significantly associated with more frequent UAVI compared to non-concordant partnerships (data not shown).

Table 2.

Associations between HIV serostatus partnership and unprotected vaginal or anal sexual intercourse by participant HIV status and by types of partners in the multivariate poisson regression modelsa

| Type of partners |

Serostatus partnership |

HIV-uninfected women (N = 664) |

HIV-infected women (N = 1602) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of partner-ships |

% of UAVI | PR | 95% CI | # of partner-ships |

% of UAVI | PR | 95% CI | ||

| All partners | Seroconcordantb | 3668 | 70.8 | 2.30 | (1.86,2.85)c | 2417 | 53.3 | 1.62 | (1.53,1.71)c |

| Unknown | 1884 | 45.1 | 1.53 | (1.22,1.91)d | 2792 | 35.7 | 1.05 | (0.98,1.13) | |

| Serodiscordant | 194 | 32.0 | 1.00 | 4666 | 32.8 | 1.00 | |||

| Main partners | Seroconcordant | 2859 | 78.8 | 2.32 | (1.89,2.86)c | 2247 | 53.5 | 1.56 | (1.47,1.65)c |

| Unknown | 729 | 64.8 | 1.93 | (1.56,2.39)c | 1628 | 42.6 | 1.21 | (1.13,1.31)c | |

| Serodiscordant | 180 | 33.3 | 1.00 | 4086 | 34.3 | 1.00 | |||

| Casual partners | Seroconcordant | 807 | 42.4 | 3.20 | (0.87,11.75) | 170 | 49.4 | 2.27 | (1.81,2.84)c |

| Unknown | 1142 | 32.0 | 2.34 | (0.64,8.60) | 1137 | 24.4 | 1.04 | (0.84,1.28) | |

| Serodiscordant | 14 | 14.3 | 1.00 | 579 | 21.8 | 1.00 | |||

| New partners | Seroconcordant | 778 | 51.3 | 1.28 | (0.79,2.08) | 255 | 52.2 | 1.79 | (1.52,2.12)c |

| Unknown | 912 | 34.3 | 0.82 | (0.50,1.34) | 869 | 22.8 | 0.76 | (0.63,0.91)d | |

| Serodiscordant | 26 | 42.3 | 1.00 | 703 | 28.7 | 1.00 | |||

UAVI unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse, PR Prevalence ratio, CI Confidence interval

GEE method was used to account for within individual correlation due to different partners of the same woman, and adjusted for age, education, income, CCH use and perception of HIV risk in the HAART era

having the same HIV serostatus between partners

P < 0.0001

P < 0.05

UAVI among Women with both HIV Seroconcordant and Nonconcordant Partners

To further examine possible serosorting in this study, we restricted our analysis to those study visits (from 154 HIV-infected and 23 HIV-uninfected) where a participant reported both HIV seroconcordant and nonconcordant sexual partners. For these women, about 41% (63 HIV-infected and 9 HIV-uninfected) reported they had UAVI only with seroconcordant partners, but not with serodiscordant or unknown partners. Furthermore, 44 women (39 HIV-infected and 5 HIV-uninfected) reported having UAVI only with seroconcordant partners during the entire follow-up period.

Discussion

We found a high prevalence of HIV status disclosure among WIHS women and their partners, which is consistent with findings from previous studies [7, 26, 27]. In addition, trends in HIV status communication increased steadily over time. Prevalence of seroconcordant partnerships has increased for HIV-uninfected women but remained stable for HIV-infected women. However, trends in UAVI remained stable within seroconcordant partnerships, which is not congruent with results from some studies among MSM [3-5]. For HIV uninfected women, this pattern of increased seroconcordant partnership, but no change in UAVI over time is important to note, because inaccurate perception or reporting of a partner’s HIV status could put them at risk of HIV infection.

Both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women had more frequent UAVI with HIV seroconcordant partners than with partners of opposite or unknown status regardless of whether the partners are main, casual or new partners. These findings are consistent with those observed among MSM [6-8]. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that about 41% of women with both HIV seroconcordant and non-concordant partners reported having UAVI only with their seroconcordant partners, but not with other types of partners. These findings are consistent with the original serosorting definition by Suerez et al. [1], Suarez and Miller [2] and the condom serosorting concept recently proposed by Snowden et al. [28].

Although the practice of limiting unprotected sex to HIV seroconcordant relationships has been suggested as an effective risk reduction strategy [3, 29], methods for ascertaining a partner’s serostatus are often faulty. Partners may not be aware of their serostatus or may not choose to disclose it, thereby placing those sexually engaged with them at risk for infection [11, 15, 16]. Our analysis showed that women in the WIHS might be at risk of HIV transmission due to perceived serosorting. In addition, HIV-uninfected women in the WIHS remained vulnerable to HIV infection as a result of having unprotected sexual intercourse with serodiscordant partners.

The strengths of our study include a longitudinal cohort design, a large sample size and well characterized high quality data. However, there are some limitations. First, we collected data only on women’s sexual behavior with her 5 most recent partners in the past 6 months. However, at 94% of study visits, women in this cohort reported no more than 5 partners and these reported partners likely account for most of these women’s sexual episodes. Second, we did not measure serosorting directly, in that we did not assess whether relationships between HIV partner concordance and condom use were mediated by decision making regarding the risk of HIV transmission/acquisition given the serostatus of a woman’s sexual partner. Hence, the women’s decision making as it pertained to having UAVI among the seroconcordant, discordant or unknown status of sexual partnerships remains unexplained in this study. Our observation of what appears to be serosorting practice warrant further investigation. Third, the accuracy of the perceived HIV status of the partner is unknown.

Conclusion

In summary, both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in the WIHS practice serosorting. Future studies on serosorting among women should explore the intent and perceived effectiveness of serosorting to prevent HIV infection, so that targeted, resilient interventions can be developed for those populations most at risk.

Acknolwedgements

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases with supplemental funding from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590). Funding is also provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632) and the National Center for Research Resources (MO1-RR-00071, MO1-RR-00079, MO1-RR-00083).

Contributor Information

Chenglong Liu, Department of Medicine, Georgetown University, 2233 Wisconsin Ave NW, Suite 214, Washington, DC 20007, USA.

Haihong Hu, Department of Medicine, Georgetown University, 2233 Wisconsin Ave NW, Suite 214, Washington, DC 20007, USA.

Lakshmi Goparaju, Department of Medicine, Georgetown University, 2233 Wisconsin Ave NW, Suite 214, Washington, DC 20007, USA.

Michael Plankey, Department of Medicine, Georgetown University, 2233 Wisconsin Ave NW, Suite 214, Washington, DC 20007, USA.

Peter Bacchetti, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Kathleen Weber, Hektoen Institute of Medicine and The CORE Center at John H. Stroger Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, IL, USA.

Nereida Correa, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA.

Marek Nowicki, Department of Pediatrics, University of South California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Tracey E. Wilson, Department of Community Health Sciences, State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

References

- 1.Suarez TP, Kelly JA, Pinkerton SD, Stevenson YL, Hayat M, Smith MD, et al. Influence of a partner’s HIV serostatus, use of highly active antiretroviral therapy, and viral load on perceptions of sexual risk behavior in a community sample of men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(5):471–7. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200112150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suarez T, Miller J. Negotiating risks in context: a perspective on unprotected anal intercourse and barebacking among men who have sex with men—where do we go from here? Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30(3):287–300. doi: 10.1023/a:1002700130455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truong HM, Kellogg T, Klausner JD, Katz MH, Dilley J, Knapper K, et al. Increases in sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk behaviour without a concurrent increase in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: a suggestion of HIV serosorting? Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):461–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao L, Crawford JM, Hospers HJ, Prestage GP, Grulich AE, Kaldor JM, et al. “Serosorting” in casual anal sex of HIV-negative gay men is noteworthy and is increasing in Sydney, Australia. Aids. 2006;20(8):1204–6. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226964.17966.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elford J, Bolding G, Sherr L, Hart G. No evidence of an increase in serosorting with casual partners among HIV-negative gay men in London, 1998–2005. Aids. 2007;21(2):243–5. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280118fdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons JT, Schrimshaw EW, Wolitski RJ, Halkitis PN, Purcell DW, Hoff CC, et al. Sexual harm reduction practices of HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men: serosorting, strategic positioning, and withdrawal before ejaculation. Aids. 2005;19(Suppl 1):S13–25. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167348.15750.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia Q, Molitor F, Osmond DH, Tholandi M, Pollack LM, Ruiz JD, et al. Knowledge of sexual partner’s HIV serostatus and serosorting practices in a California population-based sample of men who have sex with men. Aids. 2006;20(16):2081–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247566.57762.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Bij AK, Kolader ME, de Vries HJ, Prins M, Coutinho RA, Dukers NH. Condom use rather than serosorting explains differences in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(5):574–80. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180959ab7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osmond DH, Pollack LM, Paul JP, Catania JA. Changes in prevalence of HIV infection and sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men in San Francisco: 1997 2002. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1677–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golden MR, Stekler J, Hughes JP, Wood RW. HIV serosorting in men who have sex with men: is it safe? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(2):212–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin F, Crawford J, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, Imrie J, Kippax SC, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. Aids. 2009;23(2):243–52. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb51a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golden MR, Wood RW, Buskin SE, Fleming M, Harrington RD. Ongoing risk behavior among persons with HIV in medical care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(5):726–35. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Cain DN, Cherry C, Stearns HL, Amaral CM, et al. Serosorting sexual partners and risk for HIV among men who have sex with men. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6):479–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton LA, West TV, Kenny DA, Kalichman SC. HIV transmission risk among HIV seroconcordant and serodiscordant couples: dyadic processes of partner selection. AIDS Behav. 2008 Oct 25; doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9480-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons JT, Severino J, Nanin J, Punzalan JC, von Sternberg K, Missildine W, et al. Positive, negative, unknown: assumptions of HIV status among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(2):139–49. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler DM, Smith DM. Serosorting can potentially increase HIV transmissions. Aids. 2007;21(9):1218–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32814db7bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC . HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005. Vol. 17. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; Atlanta: [Accessed April 27, 2010]. 2007. pp. 1–46. Revised. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, et al. WIHS collaborative study group The women’s interagency HIV study. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review. Jama. 2004;292(2):224–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phair JP, Ostrow DG. Risk-taking in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2001;3(2):101–2. doi: 10.1007/s11908-996-0030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvelli T, Denny TN, Paxton H, Gelman R, Kagan J. Guideline for flow cytometric immunophenotyping: a report from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS. Cytometry. 1993;14(7):702–15. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990140703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DHHS [Accessed March 1, 2006];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. 2005 DHHS/Henry J. Kaiser family foundation panel on clinical practices for the treatment of HIV infection. April 2005 revision. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov.

- 23.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson TE, Gore ME, Greenblatt R, Cohen M, Minkoff H, Silver S, et al. Changes in sexual behavior among HIV-infected women after initiation of HAART. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1141–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson TE, Feldman J, Vega MY, Gandhi M, Richardson J, Cohen MH, et al. Acquisition of new sexual partners among women with HIV infection: patterns of disclosure and sexual behavior within new partnerships. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(2):151–9. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niccolai LM, Dorst D, Myers L, Kissinger PJ. Disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners: predictors and temporal patterns. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(5):281–5. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zablotska IB, Imrie J, Prestage G, Crawford J, Rawstorne P, Grulich A, et al. Gay men’s current practice of HIV seroconcordant unprotected anal intercourse: serosorting or seroguessing? AIDS Care. 2009;21(4):501–10. doi: 10.1080/09540120802270292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snowden J, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Prevalence of seroadaptive behaviors of men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2004. Sex Transm Infect. 2009 Jun 7; doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morin SF, Shade SB, Steward WT, Carrico AW, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. A behavioral intervention reduces HIV transmission risk by promoting sustained serosorting practices among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(5):544–51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5def. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]