Abstract

Monoamine oxidases (MAO-A and MAO-B) have a key role in the degradation of amine neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin. We identified an inherited 240 kb deletion on Xp11.3–p11.4, which encompasses both monoamine oxidase genes but, unlike other published reports, does not affect the adjacent Norrie disease gene (NDP). The brothers who inherited the deletion, and thus have no monoamine oxidase function, presented with severe developmental delay, intermittent hypotonia and stereotypical hand movements. The clinical features accord with published reports of larger microdeletions and selective MAO-A and MAO-B deficiencies in humans and mouse models and suggest considerable functional compensation between MAO-A and MAO-B under normal conditions.

Keywords: monoamine oxidase, MAOA and MAOB, array CGH, X chromosome, abnormal hand movement

Introduction

Monoamine oxidases, MAO-A and MAO-B, catalyse the oxidative deamination of biogenic and dietary amines. Monoamine oxidase (MAO) substrates include neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine, and the neuromodulator phenyleythylamine (reviewed in Shih and Thompson1). The rapid degradation of bioactive monoamines by MAO isoenzymes is essential for appropriate synaptic neurotransmission, and monoaminergic signalling affects motor, perceptual, cognitive and emotional brain functions.2 The MAOA and MAOB genes occur in tandem, suggesting an ancestral duplication event, but lie in opposite orientations on Xp11.23, where they share 70% identity at the amino-acid level and exhibit an identical organization of their 15 exons.3, 4 Despite this sequence similarity, MAO-A and MAO-B have distinct but overlapping substrate specificities and spatial and temporal expression patterns in the brain and peripheral tissues, although most tissues express both isoenzymes.5, 6, 7

Previous reports of MAO gene deletions have always encompassed the adjacent NDP gene and are associated with an atypical presentation of Norrie disease (ND, OMIM no. 310600). ND is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by congenital blindness because of bilateral retinal malformation and lens opacity. To date, over 70 pathogenic NDP mutations have been identified.8, 9, 10 Accessory phenotypes in ‘classical' ND include progressive sensorineural deafness in approximately one-third of cases and some degree of intellectual disability, autism or psychosis in over 50% of cases.11 Atypical ND patients with a contiguous deletion of NDP and both MAO genes present with a more severe neurological involvement, with profound psychomotor and verbal deficits.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Affected individuals have also been noted to have growth retardation, seizures and display manneristic, self-injurious behaviours and often have delayed sexual maturation.

The clinical presentation of rare individuals with selective loss of either MAOA or MAOB offers a marked contrast to the severe phenotype associated with the deletion of both MAO genes and NDP. In a single reported ND family with a deletion spanning NDP and MAOB only, no intellectual impairment or behavioural disturbances were noted.18 Selective MAO-A deficiency has been described in a large Dutch kindred with borderline mental retardation and abnormal behaviour, which manifests specifically as impaired impulse control and increased aggression.19 Affected individuals in this pedigree had a point mutation that prematurely truncated the MAO-A protein.20 Lenders et al18 showed that patients with dual MAOA/B loss (with NDP), selective MAOA deficit and selective MAOB deficit (with NDP) have distinct biochemical profiles of catecholamines and their metabolites, which suggests that this likely explains the different clinical phenotypes of each mutation category.

In this study, we report the clinical and molecular characterization of a submicroscopic deletion of MAOA and MAOB genes without the concomitant deletion of NDP. This mutation affords the opportunity to further dissect the phenotypic consequences of MAO deficiency.

Clinical report

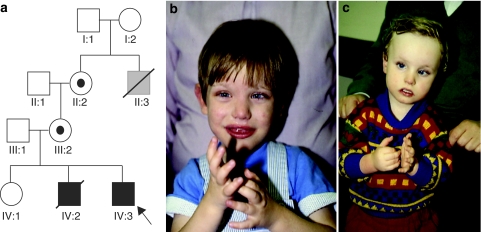

Figure 1a shows an X-linked pedigree in which two brothers (IV:2 and IV:3, pictured in Figure 1b and c, respectively) presented with severe mental retardation, hand wringing, lip smacking and epilepsy. The brothers were born to a healthy non-consanguineous Caucasian couple; the mother was 30-years old and the father was 31-years old at the birth of IV:2; an older daughter was healthy. The maternal grandmother had a male sibling who died around 2 years of age and had slow development, but no further medical records were available.

Figure 1.

(a) Pedigree of the family; IV-2 (b) and IV-3 (c). Both individuals illustrate the typical hand posturing observed.

IV:2 was born by normal delivery with a birth weight of 2.38 kg at about 36 weeks gestation after a normal pregnancy. He was noted to be hypotonic in the newborn period and fed poorly, necessitating tube feeding. In the first 6 months, he had several attacks of sudden profound hypotonia, which was thought to represent seizures; EEG showed short-wave activity in the occipital area and he was treated at 9 months with phenobarbital, followed by sodium valproate. These episodes continued in spite of the medication. A CT scan showed widening of the ventricles and basal spaces. All investigations for metabolic disorders and viral infections were negative. His development was significantly delayed, he sat at 20 months and walked with support at 2 years 6 months; he never walked independently. At 4 years, his OFC was between the 3rd and 10th centiles and his weight and length were just below the 3rd centile. He had recurrent screaming episodes with head banging and hand flapping; he scratched his face and chewed his hands. He had no major dysmorphic features but had inner canthal folds, long eyelashes, an extra upper lateral incisor and an unusual hair whorl on his posterior hairline. He died unexpectedly at 5 years of age. His autopsy did not reveal any abnormalities of his internal organs except for his brain, which was mildly underweight and on microscopy showed small foci of perivascular calcification, occasional haemosiderin granules in the Virchow–Robin spaces, loss of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum and some loss of neurons in the cortex.

IV:3 was born by vertex delivery at 38 weeks gestation after a normal pregnancy and weighed 2.5 kg. In the newborn period, he was noted to make jerky movements when falling asleep or waking up. Soon after, he began to have episodes of hypotonia similar to his brother. He began to purse and smack his lips and had an intermittent convergent strabismus. At 13 weeks he had definite axial hypotonia and from 10 months he developed writhing movements of his hands. His 48 h EEG recording was normal. He sat at 15 months, bottom shuffled at 2 years 8 months and walked independently at 4 years. Facially, he resembled his brother and also had inner canthal folds and long eyelashes. He continued to have episodes of restlessness, followed by hypotonia, eye flickering and loss of consciousness lasting around 30 s. They seemed more frequent when he awoke and when placed on the toilet. He seemed to be able to induce these himself by lying on the floor, staring at a light and shaking his head from side to side. Treatment with lamotrigine 100 mg twice daily was tried between the ages of 6 years and 8 years and, although initially the episodes seemed less frequent, they subsequently increased up to between 20 and 30 times per day, whereby treatment was stopped. The MRI scan of his brain did not reveal any abnormalities. At 15 years, his OFC was between the 3rd and 10th centiles, his height was on the 0.4th centile and his weight was on the 25th centile. He walked independently and could run clumsily. He enjoys social events and company and communicates with many single words and British sign language. His episodes of hypotonia continue. During these episodes, he becomes pale and may drop to the ground. Recently, an EEG was performed during one of these episodes, which showed no focal signs or paroxysmal features. Numerous previous investigations for cytogenetic abnormalities, for mutations in MECP2, FRAXA and ARX and isoelectric focusing screening for CDG deficiency were all normal.

Methods

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and lymphoblastoid cell lines obtained from the proband (IV:3) and his mother using standard protocols. No additional family samples were available for analysis. Appropriate clinical research ethics review board (MREC) approval was obtained for the studies at the University of Cambridge and University of Manchester. Clinical data were obtained from the family with informed consent.

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) was performed using a custom-designed X-chromosome-specific Nimblegen 385K oligonucleotide microarray (full details of array design available on request). Hybridizations were performed by the Roche Nimblegen Inc. service laboratory (Reykjavik, Iceland) according to standard protocols. Hybridization was carried out against a reference normal human male of Caucasian origin (NA10851; obtained from the Coriell Cell Repository, Camden, NJ, USA). A single hybridization experiment was conducted, with patient DNA labelled with Cy5-dCTP and the reference individual with Cy3-dCTP. After data normalization, array analysis was performed using the ADM-1 calling algorithm (Agilent CGH Analytics version 3.4). 250K Nsp GeneChip array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) whole-genome analysis was also performed using standard published protocols.21 Dual-colour fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was carried out on metaphase chromosome spreads with PAC probes selected from the Sanger Institute whole-genome tile path 30k clone set to confirm the deletion in the proband using standard techniques. Metaphases were examined using an Olympus BX61 fluorescent microscope and images were captured using a Hamamatsu ORCA camera and Smartcapture 3 software.

Long-range PCR was used to amplify a PCR product spanning the deletion junction. Primers were designed to flank the deletion: JF_F: 5′-GAGATAATGAAATCTACTCCAAGGGATGGTTG-3′ and JF_R: 5′-TATCAGGGCTTATATGATCAGTCACTGGAGAG-3′. PCR was performed with 150 ng genomic DNA in a 50 μl reaction containing 2.5 U LaTaq (TaKaRa Bio Inc, Otsu, Shiga, Japan), 1 × GC Buffer I, 400 μ each dNTP and 400 n each primer. Thermal cycling, gel purification and direct Sanger sequencing of products were performed using standard protocols. Subsequent rounds of sequencing using nested primers (JF_int1: 5′-TCTTGCTCTCTGGTGCCATTC-3′ and JF_int2: 5′-TTCTTTGAGACGGAGTCTTGCTC-3′) were performed to obtain sequencing reads spanning the deletion junction. The X-inactivation pattern in peripheral blood leukocytes was assessed by PCR analysis of the polymorphic exon 1 CAG repeat of the AR locus, as described in Plenge et al.22

Results

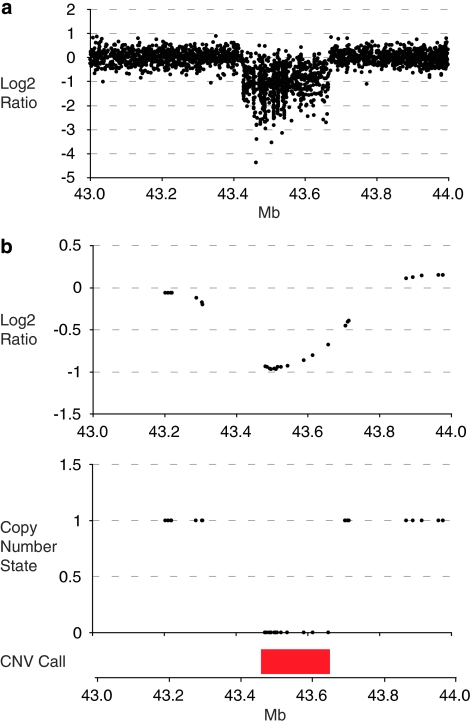

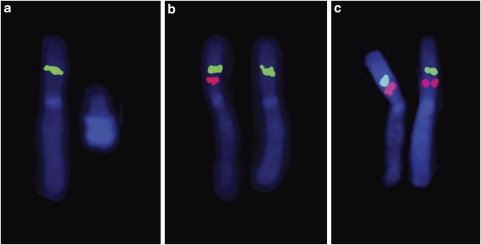

Copy number analyses using the custom X-chromosome array and 250K Nsp GeneChip array were performed in parallel. The X-chromosome array indicated a 240 kb deletion in Xp11.3 that contained exons 2–15 of MAOA and all exons of MAOB. The deletion was reported by 847 probes, with an average log2 ratio of −1.08 (Figure 2a). Using the SNP chip platform, the deletion was reported by 16 SNPs (Figure 2b). No significant deletions or duplications were identified elsewhere in the genome with the 250K SNP array. FISH analysis of a fresh lymphocyte culture from the proband using clones tiled across the region supported the array estimates of the deletion bounds (Figure 3). In addition, the gene content of the deletion was confirmed by PCR amplification of coding regions predicted to be at the flanks of the deletion (data not shown). FISH analysis of the proband's mother revealed that she was a carrier of the deletion (Figure 4). No significant skewing of X-inactivation was noted in maternal leukocytes (41:59 ratio).

Figure 2.

(a) X-chromosome array hybridization log2 ratios for the X-chromosome region 43–44 Mb. Each data point represents the Cy3/Cy5 log2 ratio of a single probe, after data normalization. (b) Copy number analysis of 250K Nsp GeneChip for the X-chromosome region 43–44 Mb. Copy number state and log2 ratios generated using the Affymetrix CN4 algorithm.

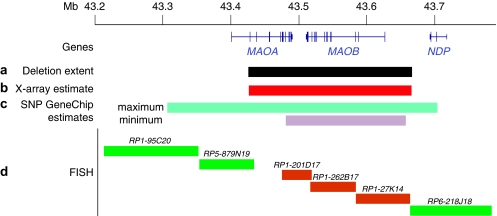

Figure 3.

Scheme showing the deletion location. The numbers are deletion coordinates (hg18). (a) Actual deletion extent. (b) X-chromsome array estimate of deletion extent. (c) Maximum and minimum SNP chip estimates of deletion extent. The minimum extent corresponds to the position of the first and last SNPs reporting the deletion, the maximum extent is defined by the location of the flanking wild-type copy number SNP calls. (d) FISH analysis of the deleted region. Green bars indicate a BAC clone that was detected by FISH, orange bars indicate BAC clones that failed to give a signal in metaphases from the proband.

Figure 4.

Representative dual-colour FISH in metaphases from the proband (a) and his mother (b) and a control female (c). Probe RP1-262B17 (red) is within the deletion and probe RP11-265D20 (green) is adjacent to the deletion (see Figure 3).

The high resolution of the X-chromosome oligo array facilitated the design of primers flanking the deletion. Using a long-range PCR strategy, an amplicon of approximately 9 kb was obtained for the proband sample but not from control individuals. Direct sequence analysis of this PCR product was performed and sequence spanning the deletion break-point junction was obtained (Figure 5). The deletion mapped to the reference sequence nucleotides 43 426 230–43 666 584 (genome build hg18). The proximal break point was contained within an L1PA7 LINE element and the distal break point within an AluY element. A BLAST2 analysis of the 2 kb genomic reference sequence flanking both break points revealed no significant sequence homologies. There was minimal sequence identity in the 30 bp surrounding each break point but there was 2 bp of microhomology at the junction itself. These features are consistent with a deletion mechanism involving a non-homologous end-joining event. No similar deletions are reported in the public access databases of genomic variants either for diseased or normal individuals.

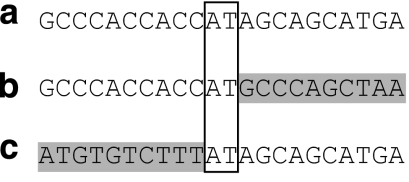

Figure 5.

DNA sequence of the deletion junction fragment. Sequence from the proband (a) is aligned to the wild-type reference sequence from the distal (b) and proximal (c) break points. The 2 bp of microhomology common to the proximal and distal break-point sequences is outlined by the box.

Discussion

We present a family with an inherited partial deletion of MAOA and a complete deletion of MAOB, resulting in loss of function of both genes. Although there are no previous reports of a genomic microdeletion affecting only MAOA and MAOB, the consequences of dual MAO loss of function can be predicted by comparing reports of probands with ND resulting from larger contiguous gene deletions or with selective MAOA loss of function.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 These reports reveal that the presence of either a functional MAOA or MAOB gene product is sufficient to preserve intellectual processing and development to within mild to borderline mental retardation levels. However, as described in this report and in atypical ND patients with dual MAO loss, deletion of both genes results in severe to profound mental retardation apparent shortly after birth, indicating that these genes are critical for early brain development and function.

In males, the loss of MAOA and MAOB is associated with severe mental retardation and unusual stereotypical behaviours of hand wringing and lip smacking. The stereotypical hand movements and lip smacking were also noted in families with loss of function mutations or deletions of MAOA.13, 19 Although these stereotypical behaviours are similar to those seen in Rett syndrome and Angelman syndrome, they have distinctive features that can provide a useful diagnostic aid. The absence of clinical manifestations in the female deletion carrier, coupled with the assumption that the random X-chromosome inactivation pattern in lymphocytes is echoed in the central nervous system itself, suggests that mosaic expression of these genes in the brain is sufficient to sustain normal neural development and function.

In a study of an atypical ND patient, Rodriguez-Revenga et al17 suggested that the co-deletion of EFHC2 underlies the seizures observed in their proband, as the paralogous EFHC1 is associated with autosomal juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.23, 24 Although seizures are uncommon in classical ND, there are examples of seizures in cases with NDP point mutations.25, 26 The occurrence of seizures in the family described here further supports a role for the disruption of several genes in this region being sufficient to cause epilepsy.

MAO inhibitors have been widely used in the past to treat severe depression and, although significant side effects are reported, long-term use is not associated with cognitive decline or with the stereotypical hand movements seen in this family. This suggests that the clinical features we observed are likely to be due to disturbances in the development of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine neuronal populations during early embryogenesis and brain formation, rather than being a reflection of altered neuronal function once normal neuronal connections have been established.

There are interesting parallels to the clinical presentations in MAO-deficient mouse models. MAOA knockout mice exhibit abnormal behaviours, including trembling and increased fearfulness as pups and increased aggression in adult males.27 MAOB knockout mice display increased reactivity to stress but, as with humans, this phenotype is relatively mild compared with MAOA loss.28 The double MAOA and MAOB knockout has an extreme behavioural hyper-reactivity compared with single knockouts, again recapitulating the more severe phenotype seen in humans and indicating partial functional redundancy between MAOA and MAOB.29

In summary, the likely clinical features of patients with dual MAO deficiency have previously been inferred from patients with selective loss of genes within the region of Xp11.2 and this case confirms the predictions. The distinct clinical phenotype of patients without MAO function should be included in the list of conditions associated with abnormal hand postures and movements.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Richard Newton for his clinical contribution to the research and the IGOLD consortium, particularly Patrick Tarpey, Michael Stratton, Gillian Turner, Jozef Gecz, Charles Schwartz and Roger Stevenson, for their continuing efforts to elucidate the genetic basis of inherited learning disability. This work was supported by NIHR through the Cambridge and Manchester Biomedical Research Centres, the Wellcome Trust and Action Medical Research.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shih JC, Thompson RF. Monoamine oxidase in neuropsychiatry and behavior. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:593–598. doi: 10.1086/302562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M, Chen K, Shih JC. Monoamine oxidase inactivation: from pathophysiology to therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1527–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY, Denney RM, Breakefield XO. Norrie disease and MAO genes: nearest neighbors. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1729–1737. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan NC, Heinzmann C, Gal A, et al. Human monoamine oxidase A and B genes map to Xp 11.23 and are deleted in a patient with Norrie disease. Genomics. 1989;4:552–559. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotra A, Pierucci F, Parvez H, Senatori O. Monoamine oxidase expression during development and aging. Neurotoxicology. 2004;25:155–165. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JC, Chen K, Ridd MJ. Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:197–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K. Organization of MAO A and MAO B promoters and regulation of gene expression. Neurotoxicology. 2004;25:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer G, Hanein S, Raclin V, et al. NDP gene mutations in 14 French families with Norrie disease. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:499. doi: 10.1002/humu.9204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveiro-Alvarez R, Trujillo-Tiebas MJ, Gimenez-Pardo A, et al. Genotype-phenotype variations in five Spanish families with Norrie disease or X-linked FEVR. Mol Vis. 2005;11:705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuback DE, Chen ZY, Craig IW, Breakefield XO, Sims KB. Mutations in the Norrie disease gene. Hum Mutat. 1995;5:285–292. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380050403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg M. Norrie's disease. A congenital progressive oculo-acoustico-cerebral degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1966. pp. 1–47. [PubMed]

- Gal A, Wieringa B, Smeets DF, Bleeker-Wagemakers L, Ropers HH. Submicroscopic interstitial deletion of the X chromosome explains a complex genetic syndrome dominated by Norrie disease. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1986;42:219–224. doi: 10.1159/000132282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnai D, Mountford RC, Read AP. Norrie disease resulting from a gene deletion: clinical features and DNA studies. J Med Genet. 1988;25:73–78. doi: 10.1136/jmg.25.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims KB, de la Chapelle A, Norio R, et al. Monoamine oxidase deficiency in males with an X chromosome deletion. Neuron. 1989;2:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu DP, Antonarakis SE, Schmeckpeper BJ, Diergaarde PJ, Greb AE, Maumenee IH. Microdeletion in the X-chromosome and prenatal diagnosis in a family with Norrie disease. Am J Med Genet. 1989;33:485–488. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320330415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FA, Murphy DL, Reiss AL, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and neuropsychiatric evaluation of a patient with a contiguous gene syndrome due to a microdeletion Xp11.3 including the Norrie disease locus and monoamine oxidase (MAOA and MAOB) genes. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:127–134. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Revenga L, Madrigal I, Alkhalidi LS, et al. Contiguous deletion of the NDP, MAOA, MAOB, and EFHC2 genes in a patient with Norrie disease, severe psychomotor retardation and myoclonic epilepsy. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:916–920. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Abeling NG, et al. Specific genetic deficiencies of the A and B isoenzymes of monoamine oxidase are characterized by distinct neurochemical and clinical phenotypes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1010–1019. doi: 10.1172/JCI118492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner HG, Nelen MR, van Zandvoort P, et al. X-linked borderline mental retardation with prominent behavioral disturbance: phenotype, genetic localization, and evidence for disturbed monoamine metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:1032–1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner HG, Nelen M, Breakefield XO, Ropers HH, van Oost BA. Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science. 1993;262:578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.8211186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart J, Black GCM, Clayton-Smith J. 4.5 Mb microdeletion in chromosome band 2q33.1 associated with learning disability and cleft palate. Eur J Med Gen. 2009;52:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plenge RM, Hendrich BD, Schwartz C, et al. A promoter mutation in the XIST gene in two unrelated families with skewed X-chromosome inactivation. Nat Genet. 1997;17:353–356. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Delgado-Escueta AV, Aguan K, et al. Mutations in EFHC1 cause juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2004;36:842–849. doi: 10.1038/ng1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina MT, Suzuki T, Alonso ME, et al. Novel mutations in Myoclonin1/EFHC1 in sporadic and familial juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Neurology. 2008;70:2137–2144. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313149.73035.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev D, Weigl Y, Hasan M, et al. A novel missense mutation in the NDP gene in a child with Norrie disease and severe neurological involvement including infantile spasms. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:921–924. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Limprasert P, Ratanasukon M, et al. Two Thai families with Norrie disease (ND): association of two novel missense mutations with severe ND phenotype, seizures, and a manifesting carrier. Am J Med Genet. 2001;100:52–55. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010415)100:1<52::aid-ajmg1214>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases O, Seif I, Grimsby J, et al. Aggressive behavior and altered amounts of brain serotonin and norepinephrine in mice lacking MAOA. Science. 1995;268:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.7792602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsby J, Toth M, Chen K, et al. Increased stress response and beta-phenylethylamine in MAOB-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1997;17:206–210. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Holschneider DP, Wu W, Rebrin I, Shih JC. A spontaneous point mutation produces monoamine oxidase A/B knock-out mice with greatly elevated monoamines and anxiety-like behavior. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39645–39652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405550200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]