Abstract

Peripheral activation can cause bystander thymocyte death by eliciting a “cytokine storm.” This event complicates in vivo studies using exogenous ligand-induced models of negative selection. A stable transgenic model that selectively eliminates peripheral CD4 cells has allowed us to analyze negative selection as direct cognate events in two T cell receptor transgenic mice, OT-II and DO11. Whereas cognate peptide induced a massive deletion in double-positive (DP) cells in mice with peripheral CD4 cells, this DP deletion was modest in mice lacking peripheral CD4 cells. Using BrdUrd and annexin V staining, we found that negative selection primarily occurs in a cohort of DP cells and the absence of single-positive (SP) cells is largely caused by reduction in the cohort of DP precursors. Moreover, the fates of DP cells and SP cells after antigen exposure were vastly different. Whereas SP cells up-regulated uniformly their CD69 and CD44 levels, increased their cell size, and survived after antigen exposure, DP cells had less CD69 and CD44 up-regulation, no size change, and promptly died. Thus, negative selection represents an “abortive” activation different from activation-induced cell death of mature T cells.

Negative selection in the thymus is a term describing clonal deletion of T cells that bear high avidity for endogenous peptide–MHC complexes. Because the frequency of antigen (Ag)-specific T cells or their precursors for any given Ag is rare in normal animals, the use of T cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic mice and the use of polyclonal stimuli in non-TCR transgenic animals have been popular for studying thymic negative selection. These in vivo models used either endogenous or exogenous Ag. Examples of the first model include male H-Y-specific TCR transgenic mice (1), MHC Ag-specific TCR transgenic mice (2), endogenous superantigen (Mls)-selecting strains of mice (3, 4), and mice transgenic for both TCR and specific Ag (5–7). These in vivo models have been instrumental in our current understanding of negative selection. However, these models cannot be manipulated easily to test, for example, the dose, variant ligands, and exposure time of ligands in the system. Furthermore, the processes of negative selection such as cell activation and cell death are difficult to visualize. Rather, only the end results of negative selection are facilely visualized. Also, as a result of negative selection, functional mature T cells for negative selecting ligands are absent, and thus comparison of the fate of mature cells and immature cells on ligand exposure becomes difficult.

The second type of in vivo models of negative selection is when selecting ligands are exogenous. Delivery of ligands normally is achieved by injecting superantigen or anti-CD3/TCR Ab into WT mice (8, 9) or Ag into TCR-transgenic mice (7, 10–13). The fate of selecting populations exposed to selecting ligands can be more easily determined. Indeed, as the negative selectable cohort of cells remains intact before encountering selecting ligands, cell death caused by negative selection can be visualized easily on the delivery of ligands (7, 10). It also allows the study of double-positive (DP) cells as well as single-positive (SP) cells (including mature peripheral T cells) in the same system. However, thymocyte deletion in these systems can also be caused nonspecifically by the concomitant widespread activation of the peripheral T cell compartment and subsequent cytokine release (11), which seriously encumbers the interpretation of many studies of negative selection.

We recently established an anti-CD4 Ab transgenic mouse (GK) that lacks peripheral CD4 cells but retains normal thymic profiles (14). To study negative selection in the absence of peripheral activation, GK Ab transgenic mice were bred to two types of TCR transgenic mice: OT-II mice (15) and DO11 mice (10). Negative selection as a cell-autonomous event was investigated in these TCR transgenic mice free of the influence of cytokines made by peripheral activation and of any mature SP cells that migrate back to the thymus.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Peptide.

OVA323–339 peptide (OVAp) was purchased from Mimotopes, Melbourne. We have produced mice transgenic for the anti-CD4 Ab, GK1.5 (14); these GK mice produce the Ab mainly from their pancreata (16). OVAp-specific, I-Ab-restricted TCR transgenic mice (OT-II mice; 425-2) and OVAp-specific, I-Ad-restricted TCR transgenic mice (DO11.10) have been described (10, 15). OT-II/GK mice were produced by crossing OT-II to GK mice. DO11/GK mice were used after back-crossing for >4 generations. Mice were given daily i.p. 0.5–1 mg of OVAp and killed at various times after injection.

Phenotypic Analysis of Thymocytes and Splenocytes.

Abs used for staining include FITC- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated-H129 (anti-CD4; Caltag, South San Francisco, CA), CyChrome- or Percp-conjugated Abs 53-6.7 (anti-CD8; PharMingen); FITC-conjugated IM7 (anti-CD44; PharMingen), FITC- or biotin-conjugated H1.2F3 (anti-CD69, PharMingen), and J11D and M1/69 for staining heat-stable antigen (HSA)/CD24. PE-conjugated H57-597 (anti-TCR β chain), PE-conjugated MR9-4 (anti-TCR Vβ5.1/5.2), and biotinylated KJ1-26 (for DO11; from Gayle Davey, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research) were used to stain TCR of WT and transgenic thymocytes. Cells were usually subjected to three-color staining with propidium iodide (PI) to exclude dead cells. Cells (106) were incubated with Ab conjugates in 50 μl of FACS buffer (2% FCS/25 mM EDTA) for 30 min on ice and analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) with cellquest or weasel software.

Apoptosis Detection by Flow Cytometry.

Annexin V/PI double staining were used to detect apoptosis (17). After surface staining in 2% FCS-PBS and washing with PBS, 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in binding buffer (10 mM Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4/140 mM NaCl/2.5 mM CaCl2). FITC-annexin V (PharMingen) was added (1 μg/ml final), with or without PI (1 μg/ml). The mixtures were incubated for 10 min in the dark at room temperature and analyzed immediately.

In Vivo BrdUrd Labeling.

For evaluating thymocyte turnover, WT and GK mice were given BrdUrd (Sigma) as two i.p. injections of 0.25 mg (4-h interval) and simultaneously in drinking water (1 mg/ml BrdUrd plus 2% glucose). Cells were evaluated for BrdUrd staining at various times. For BrdUrd “pulse–chase,” OT-II/GK mice were given two i.p. injections of BrdUrd and BrdUrd in drinking water for 3 days (by then the majority of DP and minority of SP thymocytes were labeled). After withdrawal of oral BrdUrd, half of the mice were injected i.p. with 0.5 mg of OVAp daily. Cells were analyzed for surface markers and BrdUrd staining (18).

Mixed Bone Marrow (BM) Chimeras.

Irradiated GK mice (2 doses of 5.5 Gy) were given i.v. 107 BM cells each from OT-II mice (ly5.2) and WT B6 mice (ly5.1). Mice were tested for reconstitution after 8 weeks. For experimentation, chimera mice were treated with OVAp as above.

Results and Discussion

Normal Thymocyte Development in GK Mice.

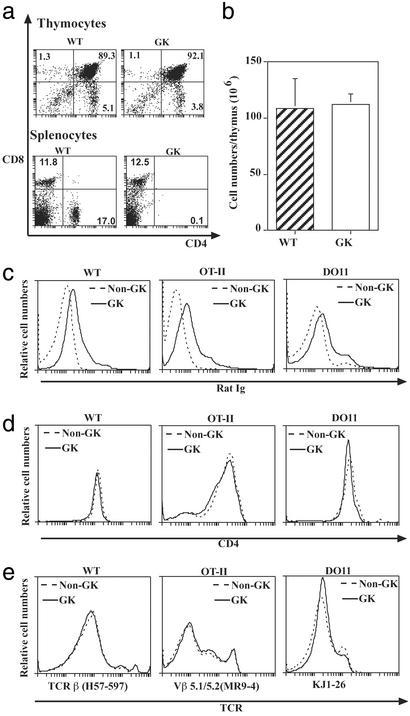

GK mice (transgenic for the rat anti-mouse CD4 Ab, GK1.5) completely lacked peripheral CD4 cells. Nevertheless, the GK thymus was unperturbed as shown by a normal distribution of subpopulations (Fig. 1a) and normal cellularity (Fig. 1b). Thymocyte turnover in GK mice was also similar to that in WT mice (data not shown). Furthermore, the population of CD69hiTCRhi DP cells appeared similar between WT and GK mice; HSA expression on SP cells also appeared similar between WT and GK mice (data not shown). To study Ag-induced negative selection that is independent of peripheral activation, we crossed GK mice to two types of TCR transgenic mice: OT-II and DO11 mice whose transgenic TCRs recognize the same OVAp on IAb and IAd, respectively.

Figure 1.

Normal thymocyte development in GK mice. (a) Cell surface expression of CD4 and CD8 on thymocyte and splenocytes. (b) Thymocyte numbers between WT and GK mice. (c) Binding of transgenic anti-CD4 Ab to thymocytes. Anti-CD4 Ab bound was detected by anti-rat Ig. Solid line, GK thymocytes; dotted line, non-GK thymocytes. (d) CD4 expression by thymocytes in anti-CD4 transgenic mice using the YTA 3.1 Ab that does not compete with GK1.5 (44). Plots show that CD4 expression on WT, OT-II, and DO11 mice was comparable in GK (solid line) and non-GK (dotted line) mice. (e) TCR expression by thymocytes in anti-CD4 transgenic mice. Plots show that TCR expression on WT, OT-II, and DO11 mice was comparable in GK (solid line) and non-GK (dot line) mice. Experiments were performed three times with similar results.

In vivo injection of Ab to CD4 and CD8 has been reported to influence CD4 and TCR expression on thymocytes and so influence CD4 T cell development (19–21). Hence, it was important to show that the transgenic anti-CD4 Ab in our system had no direct influence on T cell development. In GK mice, small amounts of transgenic anti-CD4 Ab did reach the thymus and bind to cells (Fig. 1c). However, CD4 expression by thymocytes was indistinguishable between GK and non-GK mice for both non-TCR transgenic as well as TCR transgenic OT-II and DO11 mice (Fig. 1d). TCRβ expression on thymocytes of WT mice and transgenic TCR expression (Vβ5.1/5.2) on OT-II thymocytes and clonotypic TCR KJ1-26 on DO11 thymocytes were also not influenced by residual amounts of transgenic Ab (Fig. 1e).

How Many Cells Die Through Negative Selection?

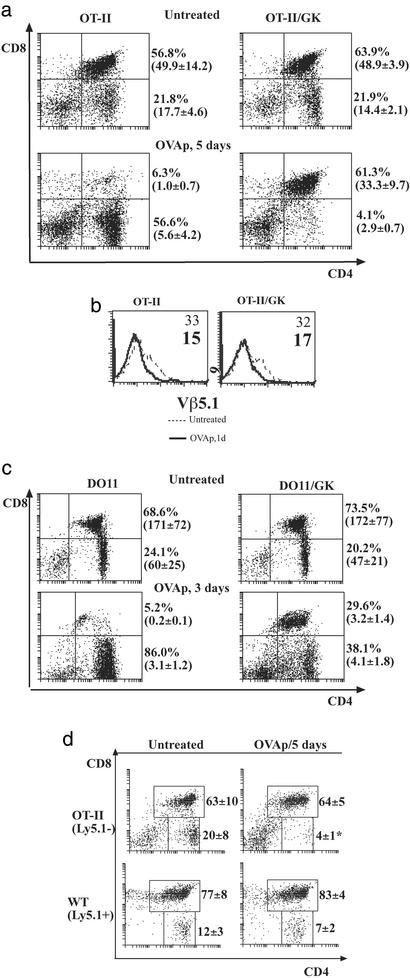

The number of thymocytes that undergo negative selection in normal animals is unclear (22). The magnitude of this deletion often varied in different in vivo models of negative selection. In the case of peptide Ag in TCR transgenic mice or anti-CD3 in WT mice, deletion is characterized by the disappearance of immature DP cells. However, much of this deletion may be caused by peripheral T cell activation via tumor necrosis factor and other cytokines (11, 23). Using GK mice, we could differentiate cell death via intrinsic TCR signaling from death resulting from peripheral effects in OT-II mice. When OT-II mice and OT-II/GK mice were given OVAp, a striking difference in thymocyte profiles was observed. OT-II mice had reduced cell numbers from 2 days after Ag injection. By day 5, DP cells were reduced 50-fold compared with those of untreated mice (Fig. 2a). We interpreted the massive DP loss in OT-II mice as the result of Ag-induced peripheral activation. Not surprisingly, the spleen in OT-II mice increased in weight after Ag injection and splenic CD4 cells in OT-II mice increased in cell size and up-regulated their CD44 expression (data not shown). In contrast, DP cells in OT-II/GK mice were only slightly reduced (e.g., from 49 million to 33 million cells; Fig. 2a) and deletion occurred mainly in TCRhi DP cells (Fig. 2b). We argue that without a peripheral CD4 compartment in OT-II/GK mice this modest depletion of DP cells represents true negative selection.

Figure 2.

OVAp-induced thymocyte deletion in TCR transgenic mice with or without peripheral T cells. (a) OVAp induced thymocyte death in OT-II and OT-II/GK mice. OT-II and OT-II/GK mice (three mice per group) were given daily doses of OVAp (0.5 mg). Plots show the thymic profiles of untreated and OVAp-treated mice. Percentages and absolute numbers (mean and SD in parentheses) of DP cells and SP cells are shown. Experiments were repeated five times with similar results. (b) Thymocytes from a were stained for CD4, CD8, and Vβ5.1/5.2. Plots show the TCR expression of DP cells in 1-day-treated and untreated OT-II and OT-II/GK mice. Numbers in the plots indicated the mean fluorescence. (c) OVAp induced thymocyte death in DO11 and DO11/ GK-mice. Mice were given daily doses of OVAp (0.5 mg). Plots show the percentages and absolute numbers (mean and SD in parentheses) of DP cells and SP cells in treated and untreated mice. Experiments were performed three times with similar results. (d) Thymocyte deletion in mixed BM chimera GK mice. GK mice were lethally irradiated and then reconstituted with 107 BM cells (mix of Ly5.1−OT-II BM cells and Ly5.1+ WT BM cells). Eight weeks after reconstitution, mice (three mice per group) were given daily i.p. injection of OVAp and thymocytes were stained for CD4, CD8, and Ly5.1. Plots show thymic profiles of OT-II origin (Ly5.1−) and WT origin (Ly5.1+). Mean percentage and SD of subsets are indicated. Three similar experiments were performed.

CD4 SP cells in OT-II/GK mice reduced gradually in numbers and by day 5 after Ag injection, the population had reduced 4-fold (Fig. 2a). By 9 days after daily Ag treatment, there were very few SP cells (<0.1%). The data suggest that as each cohort of DP cells with substantial levels of TCR is deleted in OT-II/GK mice, the numbers of their derivative SP cells were thus reduced (even though there was no massive DP cell death). Our conclusion that only a cohort of DP cells is negatively selected is consistent with some early studies (24, 25).

The size of DP cohort that is deleted probably depends on the number of cells with a high enough level of TCR-to-ligand interaction to deliver death signals (reflecting both the density and avidity of the interacting surface molecules). In OT-II/GK mice, the fraction of DP cells bearing at least moderate levels of TCR was small and so the numbers of cells negatively selected were similar to those found in some endogenous Ag/TCR transgenic systems (13). In other endogenous systems (1, 26), death of DP cells can be very prominent. We surmised that this circumstance could occur without peripheral influence, when the proportion of DP cells expressing substantial TCR levels is large, e.g., DO11 mice (although the TCR levels are still lower than those of SP cells); compare in OT-II mice, only a small proportion of DP cells has medium levels of TCR (Fig. 1e). Moreover, mature DO11 cells require 10 times less Ag for optimal stimulation than mature OT-II cells (27), and we would extrapolate that the avidity threshold to stimulate DO11 DP cells would also be less. Indeed, when the DO11/GK mice were given the same dose of the same peptide, there was a more severe reduction in the DP population (Fig. 2c) compared to the mild reduction in OT-II/GK mice (Fig. 2a). As was found for the OT-II mice, peripheral activation greatly influenced DP cell fate; DP deletion was much greater by day 3 in DO11 compared with DO11/GK mice (Fig. 2b).

In GK mice where there is no peripheral influence the number of DP cells that were deleted cell-autonomously by cognate recognition of specific Ag can be clearly revealed. We found that the magnitude depends on the abundance of the DP cohort that has high enough TCR avidity, e.g., this effect is less for OT-II compared with DO11 (27). It should be noted that the levels of TCR on DP cells in WT mice are similar to those in OT-II mice and considerably less than for DO11 mice when thymocytes from all strains were stained for TCR by using the same pan-TCRβ Ab H57-597 (data not shown); hence, the size of the cohort that is negatively deleted in OT-II mice may be more representative of normal.

Does Activation Within the Thymus Cause Noncell-Autonomous Deletion?

There was a remote possibility that activation of cells within the thymus may also elicit a bystander effect. To determine whether activation of SP CD4 thymocytes could do this, we constructed mixed BM chimera in GK mice. Thymocytes of mixed chimera mice were uniformly composed of 10% OT-II originated cells (Ly5.1−) and 90% WT originated cells (Ly5.1+). In reconstituted GK mice, OVAp-induced reduction of DP cells occurred only for OT-II-derived cells (from 3.9 ± 0.6 to 2.2 ± 0.5 × 106 by 5 days after peptide injection) but not for WT DP cells (Fig. 2d). Likewise, numbers of OT-II-derived SP cells in these double BM-reconstituted GK mice were reduced on Ag exposure (from 1.4 ± 0.2 to 0.1 ± 0.1 million) after 5 days of Ag treatment, whereas numbers of CD4 SP cells of WT origin was not significantly reduced by Ag treatment. These findings confirm that the Ag-induced deletion in GK mice is a TCR-mediated intrinsic event, and that in contrast to peripheral activation, activation of SP thymocytes does not induce massive death of bystander cells.

Which Cells Die Through Negative Selection?

Negative selection has been described to occur at various stages of thymic development: throughout (28), at the SP stage (9), or most commonly at the DP stage (1, 7, 10–13, 26). There are at least three explanations for these conflicting conclusions: (i) the variation in TCR density and synapse avidity in the system used, (ii) peripheral activation not taken into account in many of these systems (therefore not solely looking at cell-autonomous events), and (iii) reduction of SP cell numbers as a consequence of death of DP precursors.

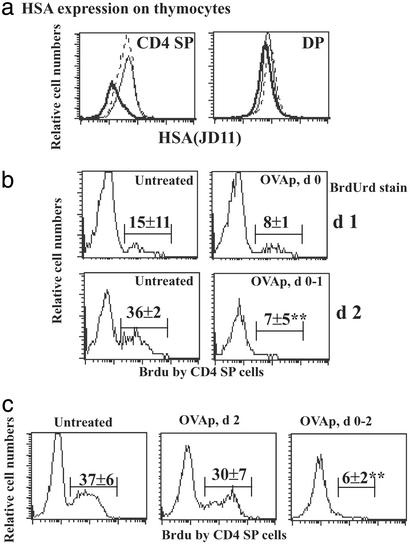

We have already discussed the first two possibilities but wanted to address the third further, especially given the Sprent laboratory's findings that thymocyte deletion by anti-TCR Ab was shown to occur in HSAhigh “semimature” CD4 SP cells (9) such that by day 1 this population was 50% reduced. Using two anti-HSA Abs, J11D as used in the original report (9) and M1/69 (29), we could not delineate two distinct populations in the SP CD4 compartment in our TCR transgenic mice (OT-II, OT-II/GK, DO11, and DO11/GK) although peptide exposure did result in overall reduction in HSA on CD4 SP cells (Fig. 3a and data not shown).

Figure 3.

(a) HSA expression on thymocytes of OT-II/GK mice. OT-II/GK mice were either untreated (dot line) or treated with OVAp (0.5 mg) for 1 day (solid line) or 3 days (thick solid line). All mice were killed at the same time, and thymocytes were stained for CD4, CD8, and HSA. Plots show HSA expression on gated CD4 SP cells and DP cells. (b) BrdUrd labeling of thymic CD4 SP cells. OT-II/GK mice were fed with BrdUrd for 3 days (between day −3 and day 0). After withdrawal of BrdUrd, mice were treated with daily doses of 1 mg of OVAp (days 0 and 1) or left untreated. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting for CD4, CD8, and BrdUrd was done on days 1 and 2. Plots show the BrdUrd labeling of CD4 SP cells; percentage means and SD of BrdUrd+ SP cells out of total SP cells from three mice per group are annotated. Three similar experiments were performed. (c) Similar to b except that one group of three mice was given 1 mg of OVAp on day 2 (Center) and all mice were analyzed together on day 3.

To distinguish between DP deletion resulting in subsequent reduction of SP cells, or direct SP deletion during the negative selection process, we identified newly derived SP cells from the existing pool, by using an in vivo BrdUrd pulse–chase technique. OT-II/GK mice were given BrdUrd i.p. at day −3 and orally on days −3 to 0. Like others (30), we have found that it takes 3 days of labeling before SP cells are BrdUrd-positive (consistent with the 3 days required for DP cells to mature into SP cells) (24, 30). By day 0, the majority of DP cells (>95%) were labeled (data not shown). After BrdUrd withdrawal at day 0, mice were i.p.-injected daily with 1 mg OVAp and cells were analyzed at 1–2 days after peptide treatment. In untreated mice, BrdUrd+ CD4 SP cells (representing newly derived SP from BrdUrd+ DP cells) gradually appeared so that by day 2 36% (3.3 ± 1.1 × 106) were BrdUrd+ (Fig. 3b). Peptide treatment for 2 days reduced BrdUrd+ SP cells dramatically to 7% (0.6 ± 0.5 × 106). In contrast, the total number of BrdUrd− CD4 SP cells reduced only modestly (from 7.0 ± 1.8 × 106 in untreated to 4.5 ± 1.3 × 106 in mice treated with OVAp for 2 days). Thus, reduction was more prominent in the newly derived SP cells rather than in the existing SP pool. To test whether reduction in newly derived (BrdUrd+) SP cells was caused by direct deletion at the SP cell stage, BrdUrd-pulsed (between day −3 and day 0) mice were untreated, given peptide once on day 2, or given peptide each day on days 0–2 (Fig. 3c). All mice were analyzed on day 3. Whereas there was only minor reduction in BrdUrd+ CD4 SP cell numbers after 24 h (from 37% to 30%; Fig. 3b), 3 days of Ag exposure reduced BrdUrd+ SP cells dramatically (from 37% to 6%). We argue that the reason it takes >1 day (compare death within 1 day in DP cells) to see significant reduction in newly derived SP numbers is that this is the time required to see the effect of eliminating the cohort of DP precursors and that the bulk of newly derived BrdUrd+ SP cells are not sensitive to Ag-induced cell death.

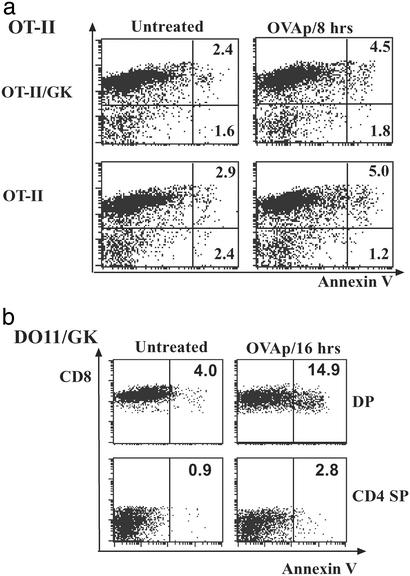

To confirm that Ag-induced death occurs primarily in the DP stage, we directly detected in vivo apoptosis by annexin V staining (excluding PIhi cells). In OT-II/GK mice, there was increased annexin V staining in DP cells (about double) but no change in SP cells 24 h after Ag injection (Fig. 4a). As expected from the larger population of DP cells that expressed TCR, apoptosis of DP cells was even more prominent in DO11/GK mice (Fig. 4b). Cell death in DO11/GK mice was readily detectable within 6 h after Ag injection (data not shown). Although annexin does detect dying cells very early, a caveat to our findings is that a proportion of dying cells may have already been engulfed by macrophages or other cells and hence rendered undetectable.

Figure 4.

(a) Annexin V staining of OT-II thymocytes. OT-II and OT-II/GK mice were given OVAp i.p. and killed 8 h later. Thymocytes were stained for CD4, CD8, annexin V, and PI. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was performed immediately. Plots show the annexin V staining of subpopulations after gating out cells with high PI; also shown are the percentages of annexin+ cells of corresponding populations (CD8+ representing DP cells, CD8− cells representing SP cells). (b) Annexin V staining of DO11/GK thymocytes. Thymocyte death was then analyzed as for a 16 h after OVAp injection. Experiments were performed three times with similar results.

If reduction of SP cells was caused by death of the immediate DP precursors, more pronounced depletion of CD4 SP cells should have been observed in mice where the DP cell death was more severe. This effect is clearly evident for both DO11 and DO11/GK mice. Although this effect is less clear for OT-II mice, we think this result is partly because the deletion in DP is far less dramatic and so one would expect less depletion in the SP cells. Moreover, with the lower cell numbers involved in the OT-II mice, it becomes difficult to make comparisons between OT-II and OT-II/GK mice as the contribution of SP from the migration of activated peripheral CD4 cells into the thymus may now become proportionately substantial in OT-II mice. This complication of the thymocyte profile does not happen in GK mice, because there are no peripheral CD4 T cells. Thus, the combined findings support our tenet that negative selection occurs mainly at the DP cell stage.

How Do Thymocytes Die Through Negative Selection?

Activation-induced cell death has been ascribed to both negative selection and death of activated peripheral T cells (31, 32). However, the two follow different kinetics. Death of DP cells occurs very early after encountering Ag or anti-CD3/TCR Ab (by day 1) whereas death of mature T cells was much delayed (3–5 days), usually after proliferation (12, 33, 34). Only under very restricted conditions, can TCR engagement render mature naïve T cells to die early (35). In our models without peripheral CD4 cells, death of a DP cohort but not SP cells occurred within a few hours after Ag injection. It raises the question of why the fate of DP cells differs from SP cells? We propose that the signal quality may be different between immature and mature T cells.

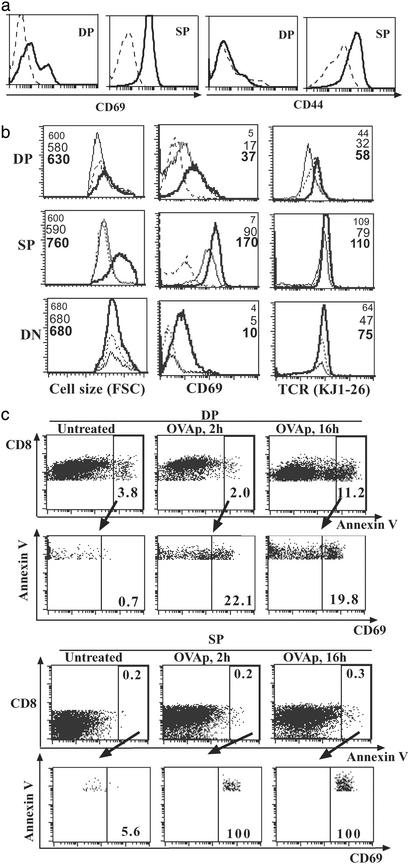

Several in vitro studies have indicated that DP cells become activated by ligation of TCR during negative selection. Apoptotic DP cells were found to increase their TCR and CD69 expression in an in vitro system, with or without TCR ligation (9, 36). Subsequently, Ag was found to induce CD69 up-regulation by TCR transgenic DP thymocytes in vitro (22). We wanted to investigate cell-autonomous activation in vivo by looking early after Ag injection (before the cells were deleted). In OT-II/GK as well as OT-II mice, CD69 and CD44 were up-regulated in SP CD4 cells within a few hours after Ag injection (data not shown). However, there was no appreciable increase in CD69 and CD44 expression on DP cells. This result may in part be biased by the small TCR+ DP population in the OT-II system. Therefore we looked in DO11/GK mice. Like in the OT-II system, the CD69 up-regulation on DP cells in DO11/GK mice was also not as marked as on SP cells (Fig. 5a), and expression of CD44 was up-regulated on SP cells but not on DP cells (Fig. 5a) in DO11/GK mice after Ag injection. The same pattern was observed in DO11 mice without GK transgene (data not shown).

Figure 5.

(a) Expression of activation markers CD69 and CD44 by thymocyte subpopulation. DO11/GK mice were given 1 mg of OVAp, and thymocytes were analyzed 16 h later for CD4, CD8, and CD69 or CD44. Histogram plots show the CD69 or CD44 expression on gated thymic populations. Dotted lines represent untreated mice and solid lines represent OVAp-treated mice. Three experiments were performed with similar results. (b) Kinetic changes of CD69, cell size, and TCR expression on thymocyte subsets after OVAp injection. Thymocytes of DO11 mice were analyzed at 0 h (untreated) or 2 or 16 h after OVAp injection. Gated thymic subpopulations [DP, SP, and double negative (DN)] from untreated (dotted line), 2-h-treated (thin solid line), and 16-h-treated (thick solid line) mice were shown for their relative size, CD69 expression, and TCR expression; the mean fluorescence intensities are also annotated in corresponding order. Experiments were performed three times with similar results. (c) Activation marker expression by dying thymocytes. Thymocytes of DO11 mice at 0 h (untreated) or 2 or 16 h after OVAp injection were stained for CD8, CD69, and annexin V; cells with high PI were gated out. Dying DP and SP cells were gated as annexin V+CD8+ and V+CD8− cells. These cells were then shown for their CD69 expression. The percentage of each framed population is indicated.

Subsequently, DO11 mice were used to study the kinetic change of activation marker, cell size, and TCR expression of thymocyte subsets. By CD69 and CD44 phenotyping, the level of activation of DP cells would seem to be less than that of SP cells. This effect was highlighted by the lack of increase in cell size in DP cells after peptide injection, whereas SP cells uniformly increased in size by 16 h (Fig. 5b). Despite CD69 up-regulation, DP cells did not increase in cell size between 2 and 16 h after peptide injection. To determine how activation was linked to cell death, we compared annexin V staining as a marker of early apoptosis and CD69 expression at 2 and 16 h after peptide injection. As expected, at 16 h the majority of dying (annexin Vhigh) cells were found in the DP compartment (Fig. 5c). However, only a modest proportion (20%) of annexin Vhigh (dying) DP cells had increased levels of CD69, whereas 100% of annexin Vhigh SP cells had very high levels of CD69 (Fig. 5c) at 2 or 16 h after peptide injection.

We conclude that the selective death of DP cells is not necessarily associated with classical signs of activation: there is no up-regulation of CD44, the majority of dying DP cells do not have up-regulated CD69, and there is no increase in cell size. With respect to activation status, SP cells would seem to receive a stronger signal than DP cells and yet the former are not deleted per se. Therefore, this result seems to argue against any simplistic proposition that negative selection is solely caused by “too strong a signal.” We favor the view that as well as TCR avidity some intrinsic property of that stage of thymocytes also determined their fate.

TCR density on DP cells is usually lower than on SP cells. The difference in TCR density/avidity might somewhat decide cell fate (37–40). However, it is hard to differentiate whether the differences in sensitivity/activation between DP cells and SP cells are caused by TCR density/avidity effects or intrinsic effects. For example, TCR/CD28 engagement on DP cells did not induce lipid raft polarization (41) and CD3 molecules of negative selecting DP cells did not form a stable central aggregation that is associated with activation of mature T cells (42); in both of these cases, TCR or intrinsic effects cannot be differentiated. However, there are some studies that shed light on events independent of TCR density/avidity. Mature CD4 cells whose available TCR numbers have been reduced (by monovalent Ab blockade) to below the levels of mature DP cells still proliferated perfectly in response to cognate peptide (40). In another way of looking at intrinsic properties independent of TCR, one study (43) showed that NF-AT binding activity was not induced in response to phorbol myristate acetate/lonomycin (or Ag) in DP cells, whereas it was induced in SP cells.

From the above, we opine that negative selecting populations (primarily DP) have a low capacity to undergo full activation compared with mature cells. This abortive activation may selectively direct the response to a death pathway. Comparison of the different behaviors of DP cells and SP cells induced by agonists may aid to dissect negative selection processes.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the memory of Dr. Tom Mandel (who died May 28, 2002), a jocular friend and colleague who taught A.M.L. how to graft thymuses. We thank Prof. K. Shortman and A/Prof F. Carbone for reading this manuscript and Dr. C. Benoist for early talks while on sabbatical at The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Support was granted from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, National Institutes of Health, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Diabetes Australia, and Appel Estate.

Abbreviations

- Ag

antigen

- TCR

T cell receptor

- DP

double-positive

- SP

single-positive

- OVAp

OVA323–339 peptide

- PI

propidium iodide

- BM

bone marrow

- HSA

heat-stable antigen

References

- 1.Kisielow P, Bluthmann H, Staerz U D, Steinmetz M, von Boehmer H. Nature. 1988;333:742–746. doi: 10.1038/333742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viret C, Sant'Angelo D B, He X, Ramaswamy H, Janeway C A., Jr J Immunol. 2001;166:4429–4437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappler J W, Staerz U, White J, Marrack P C. Nature. 1988;332:35–40. doi: 10.1038/332035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald H R, Schneider R, Lees R K, Howe R C, Acha-Orbea H, Festenstein H, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. Nature. 1988;332:40–45. doi: 10.1038/332040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foy T M, Page D M, Waldschmidt T J, Schoneveld A, Laman J D, Masters S R, Tygrett L, Ledbetter J A, Aruffo A, Claassen E, et al. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1377–1388. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams C B, Engle D L, Kersh G J, Michael White J, Allen P M. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1531–1544. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wack A, Ladyman H M, Williams O, Roderick K, Ritter M A, Kioussis D. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1537–1548. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.10.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page D M, Roberts E M, Peschon J J, Hedrick S M. J Immunol. 1998;160:120–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kishimoto H, Sprent J. J Exp Med. 1997;185:263–271. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy K M, Heimberger A B, Loh D Y. Science. 1990;250:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.2125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin S, Bevan M J. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2726–2736. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liblau R S, Tisch R, Shokat K, Yang X, Dumont N, Goodnow C C, McDevitt H O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3031–3036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zal T, Volkmann A, Stockinger B. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2089–2099. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan Y, Corbett A J, Brady J L, Sutherland R M, Lew A M. J Immunol. 2000;165:3612–3619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnden M J, Allison J, Heath W R, Carbone F R. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhan Y, Brady J L, Johnston A M, Lew A M. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19:639–645. doi: 10.1089/10445490050199045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermes I, Haanen C, Steffens-Nakken H, Reutelingsperger C. J Immunol Methods. 1995;184:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00072-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tough D F, Sprent J. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1127–1135. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy S A, Kruisbeek A M, Uppenkamp I K, Sharrow S O, Singer A. Nature. 1988;336:76–79. doi: 10.1038/336076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuniga-Pflucker J C, McCarthy S A, Weston M, Longo D L, Singer A, Kruisbeek A M. J Exp Med. 1989;169:2085–2096. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDonald H R, Hengartner H, Pedrazzini T. Nature. 1988;335:174–176. doi: 10.1038/335174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merkenschlager M, Graf D, Lovatt M, Bommhardt U, Zamoyska R, Fisher A G. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1149–1158. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer J A, Kanagawa O, Sleckman B P, Muglia L J. J Immunol. 2002;169:1837–1843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egerton M, Scollay R, Shortman K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2579–2582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hugo P, Boyd R L, Waanders G A, Petrie H T, Scollay R. Int Immunol. 1991;3:265–272. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bogen B, Dembic Z, Weiss S. EMBO J. 1993;12:357–363. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson J M, Jensen P E, Evavold B D. J Immunol. 2000;164:4706–4712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldwin K K, Trenchak B P, Altman J D, Davis M M. J Immunol. 1999;163:689–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alterman L A, Crispe I N, Kinnon C. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1597–1602. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huesmann M, Scott B, Kisielow P, von Boehmer H. Cell. 1991;66:533–540. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green D R, Bissonnette R P, Glynn J M, Shi Y. Semin Immunol. 1992;4:379–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton K, Harris A W, Bath M L, Smith K G, Strasser A. EMBO J. 1998;17:706–718. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sytwu H K, Liblau R S, McDevitt H O. Immunity. 1996;5:17–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renno T, Hahne M, MacDonald H R. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2283–2287. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kishimoto H, Sprent J. J Immunol. 1999;163:1817–1826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kishimoto H, Surh C D, Sprent J. J Exp Med. 1995;181:649–655. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashton-Rickardt P G, Bandeira A, Delaney J R, Van Kaer L, Pircher H P, Zinkernagel R M, Tonegawa S. Cell. 1994;76:651–663. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hogquist K A, Jameson S C, Heath W R, Howard J L, Bevan M J, Carbone F R. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sebzda E, Wallace V A, Mayer J, Yeung R S, Mak T W, Ohashi P S. Science. 1994;263:1615–1618. doi: 10.1126/science.8128249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McNeil L K, Evavold B D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4520–4525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072673899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebert P J, Baker J F, Punt J A. J Immunol. 2000;165:5435–5442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richie L I, Ebert P J, Wu L C, Krummel M F, Owen J J, Davis M M. Immunity. 2002;16:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon A K, Auphan N, Schmitt-Verhulst A M. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1421–1428. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.9.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darby C R, Morris P J, Wood K J. Transplantation. 1992;54:483–490. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199209000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]