Abstract

Though the most recognizable symptoms of Parkinson's disease (PD) are motor-related, many patients also suffer from debilitating affective symptoms that deleteriously influence quality of life. Dopamine (DA) loss is likely involved in the onset of depression and anxiety in PD. However, these symptoms are not reliably improved by DA replacement therapy with L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA). In fact, preclinical and clinical evidence suggests that L-DOPA treatment may worsen affect. Though the neurobiological mechanisms remain unclear, recent research contends that L-DOPA further perturbs the function of the norepinephrine and serotonin systems, already affected by PD pathology, which have been intimately linked to the development and expression of anxiety and depression. As such, this review provides an overview of the clinical characteristics of affective disorders in PD, examines the utility of animal models for the study of anxiety and depression in PD, and finally, discusses potential mechanisms by which DA loss and subsequent L-DOPA therapy influence monoamine function and concomitant affective symptoms.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, L-DOPA, anxiety, depression, affect, animal models, serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine

1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects dopamine (DA) neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc). The loss of DA from nigral projections leads to difficulty with movement, including slowness or lack of movement, rigidity, postural instability, and resting tremor. Though less acknowledged, PD patients also suffer from a variety of non-motor symptoms, including significant changes in affect that deleteriously impact their quality of life (Carod-Artal et al., 2008; McKinlay et al., 2008; Schrag, 2006). L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) has been the gold standard for PD pharmacotherapy and the majority of patients will receive it at some point during their treatment. However, there may be an association between DA replacement therapy and psychological symptoms that extend beyond disease state and DA cell loss. In support, affective disorders may manifest prior to the onset of motor symptoms (Aarsland et al., 2009; Nilsson et al., 2001; Schuurman et al., 2002), neither anxiety nor depression is reliably improved by L-DOPA treatment (Kim et al., 2009; Nègre-Pagès et al., 2010), and L-DOPA may exacerbate affective symptoms in later stages of PD when its efficacy is compromised (Richard et al., 2004).

The NE and 5-HT systems are also substantially affected by the PD process in most patients (Frisina et al., 2009; Kish et al., 2008) and may be implicated in primary affective symptoms or those that result from L-DOPA treatment. For example, recent studies in animal models of PD suggest that L-DOPA may interfere with NE and 5-HT function in affect-related brain structures and induce symptoms of anxiety and depression (Eskow Jaunarajs et al., in press; Navailles et al., 2010a, 2010b). As such, this review provides an overview of the clinical characteristics of anxiety and depression in PD, examines the utility of animal models for the study of affective disorders in PD, and finally, discusses potential mechanisms by which DA loss and subsequent L-DOPA therapy influence monoamine function and concomitant affective symptoms.

2. Affective disorders in PD

Reported prevalences of affective disorders in PD are disparate, with studies reporting rates anywhere from 2% (Hantz et al., 1994) to 76% (Happe et al., 2001) for depression and 5% (Lauterbach & Duvoisin, 1991) to 69% (Kulisevsky et al., 2008) for anxiety. Nuti and colleagues (2004) observed that ~30% of patients suffering from depression in PD also experienced panic disorder and an additional 11% expressed generalized anxiety, compared to 5.5% of control populations. As notable, depression is the single most important factor in PD patients' reported quality of life, above disease severity and motor complications of L-DOPA therapy (Schrag, 2006). Furthermore, while anxiety is perhaps one of the least studied psychiatric complications diagnosed in PD patients, it is also associated with reduced quality of life (McKinlay et al., 2007).

2.1. Depression

Depressive symptoms overlap with PD symptoms and are often assumed to be synonymous with motor impairment: psychomotor retardation, attention deficit, day-night sleep reversal, weight loss, fatigue, and reduced facial expression (often called facial “masking”). In contrast to major depressive disorder, suicidal tendencies or expressions of guilt and self-blame are rarely observed in PD patients (Brooks & Doder, 2001; Lemke, 2008; Starkstein et al., 2008). Depression in PD is commonly treatment refractory, although it is possible that PD patients receive insufficient dosage of antidepressants in order to ensure that drug interactions to not worsen parkinsonism (Weintraub et al., 2003). As with anxiety symptoms, primary care physicians and caregivers either do not recognize affective symptoms or assume that PD with depression is merely a psychological side effect of chronic disease state. However, comorbidity of depression in PD (~1 in 2) exceeds that found in the general population (1 in 50; Beekman et al., 1999) or in other chronic and/or neurodegenerative diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (Chwastiak et al., 2002), Alzheimer's disease (Wragg & Jeste, 1989), and rheumatoid arthritis (Cantello et al., 1986). Furthermore, affective symptoms in PD are not influenced by the severity of motor symptoms. Multiple groups have confirmed that neither depression nor anxiety are correlated with motor disability (Huber et al., 1988; Mondolo et al., 2007; Nègre-Pagès et al., 2010; Santangelo et al., 2009; Starkstein et al., 2008; Witt et al., 2006). In fact, patients often report depression and anxiety even when their motor status is improved by pharmacotherapy or neurosurgery (Kostic et al., 1987; Marsh & Markham, 1973; Wang et al., 2009). Depression is frequently the presenting symptom before significant motor symptoms are observed, and therefore, may be considered a risk factor for PD (Aarsland et al., 2009; Nilsson et al., 2001; Schuurman et al., 2002; Tandberg et al., 1996; Ziemssen & Reichmann, 2007). As such, depression is more likely a consequence of the disease process, and not simply the result of psychological distress due to the development of a chronic disease.

2.2. Anxiety

A number of subtypes of anxiety are observed in the PD patient population, especially panic disorder, simple and social phobias, and generalized anxiety (Lauterbach et al., 2004; Pontone et al., 2009). In a recent study by Mondolo and colleagues (2007), PD patients with anxiety equated their symptoms to an inability to relax, restlessness, and feeling tense. Most investigations suggest that anxiety is more prevalent in the OFF phase of L-DOPA treatment, when the patient is lacking the beneficial effects of treatment on motor symptoms of PD (Racette et al., 2002; Stein et al., 1990; Siemers et al., 1993) and is traditionally correlated with stress due to the onset of parkinsonism. However, anxiety rates in PD populations exceed those in normal and chronic disease affected populations (Richard et al., 1996) and has been posited as a risk factor for PD, since it, like depression, may manifest before the onset of motor symptoms (Shiba et al., 2000). In fact, more severe anxiety was highly associated with onset of PD after a 12-year follow-up in patients originally suffering from simple phobias (Weisskopf et al., 2003). Such findings suggest that anxiety is not simply a factor of motor impairment alone, but reflects a neuropathological, disease-related susceptibility.

3. Effects of L-DOPA treatment on affective disorders in PD

Traditionally, L-DOPA has been reported to improve affect (Yahr et al., 1969). However, as shown in Table 1, contemporary research has been conflicting. Indeed, the only investigations in de novo PD patients have revealed that L-DOPA either does not influence (Kim et al., 2009; Marsh & Markham, 1973) or exacerbates (Choi et al., 2000; Damasio et al., 1971) depression, while even less is known of the effects of L-DOPA on anxiety.

Table 1.

Investigations of effects of L-DOPA treatment on symptoms of anxiety and depression in Parkinson's disease patients.

| Reference | Rating Scale | n | Dose of L-DOPA (mg/day) | De novo? | Treatment Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-DOPA Improves Anxiety and Depression | ||||||

| Fung et al., 2009 | PDQ-8a | 184 | 300–800 | No | 3 months | L-DOPA/carbidopa/entacapone improved mood |

| Cantello et al., 1986 | BDIb | 18 | 780h | No | NA | BDI scores improved during ON phase of treatment |

| Witt et al., 2006 | BDIb | 15 | 915h | No | Acute | Treatment improved BDI and apathy scores during ON phase |

| Funkiewiez et al., 2006 | ARCIc | 22 | 1420h | No | NA | Treatment improved anxiety and well-being during ON phase |

| Stacy et al., 2010 | WOQ-9d | 216 | NA | No | NA | Treatment improved anxiety and depression during ON phase |

| L-DOPA Does Not Affect Anxiety and Depression | ||||||

| Kim et al., 2009 | NMSSe | 23 | 376h | Yes | 3 months | Treatment did not improve anxiety or mood |

| Marsh & Markham, 1973 | MMPIf | 27 | 4440h | Yes | 3 and 15 months | Treatment did not change depression scores |

| L-DOPA Exacerbates Anxiety and Depression | ||||||

| Choi et al., 2000 | BDIb | 34 | 560h | Yes | 6–28 months | More patients were depressed after onset of treatment |

| Negre-Pages et al., 2009 | HADSg | 422 | 957h | No | NA | Treatment associated with depression |

| Damasio et al., 1970 | BDIb | 48 | 2000–5000h | Yes | >3 months | Treatment associated with exacerbation of depression and psychosis |

Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (8 question version)

Beck Depression Inventory

Addiction Research Center Inventory

Wearing-Off Questionnaire (9 question version)

Non-Motor Symptom Subscale

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory

Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale

not methyl ester form

average dose

3.1. Depression

Historically, L-DOPA treatment has been attributed to a profound recovery in mood in PD patients (Yahr et al., 1969). However, few studies have been conducted in order to confirm the effects of L-DOPA treatment on depression. Of these, slight improvements in mood have been shown in some instances (Funkiewicz et al., 2006; Growdon et al., 1998). For example, acute L-DOPA treatment was shown to reduce scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and apathy in a small group of PD patients (Witt et al., 2006). However, other studies have not confirmed the antidepressant effects of L-DOPA. In a classic study by Marsh and Markham (1973), depression was not improved even after 15 months of L-DOPA treatment in 27 de novo PD patients. A more recent study in initially de novo PD patients revealed that 3 months of L-DOPA treatment did not significantly alter mood (Kim et al., 2009). Furthermore, Choi and colleagues (2000) treated 34 de novo patients with L-DOPA for 6 and 28 months. They observed that 11 patients suffered from depression prior to L-DOPA treatment, while 14 were clinically depressed following L-DOPA treatment. In corroboration, depression was correlated with receiving L-DOPA therapy in a sample of over 400 PD patients (Nègre-Pagès et al., 2010) and depressed PD patients consistently receive higher doses of L-DOPA (Palhagen et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 2008; Weintraub et al., 2006; but see Starkstein et al., 1990).

3.2. Anxiety

While some groups have reported significant improvements in anxiety upon L-DOPA treatment (Funkiewicz et al., 2003; Maricle et al., 1995; Stacy et al., 2010), others have asserted that there is no such improvement or that L-DOPA exacerbates anxiety (Damasio et al., 1971; Richard et al., 1996; Vazquez et al., 1993). Such disparate findings may be due to the cyclic pharmacokinetic nature of chronic L-DOPA treatment, consisting of several ON/OFF phases within a 24 h period. Subtypes of anxiety due to a specific motor deficit (ie. fear of falling, agoraphobia) are substantially reduced upon onset of motor improvement due to L-DOPA treatment during the ON phase (Maricle et al., 1995, Pontone et al., 2009). Though panic attacks are usually observed in the OFF phase, they can manifest during the ON phase along with agitation and mania (Damasio et al., 1971; Pontone et al., 2009; Vazquez et al., 1993). Thus, it appears that chronic L-DOPA treatment may have enduring effects on anxiety disorders in PD. In support, Vazquez and colleagues (1993) observed that PD patients who experienced regular panic attacks were on a higher dose of L-DOPA and were more likely to experience dyskinesias and motor fluctuations than non-anxious PD patients. Though the collective data suggests that L-DOPA may be associated with exacerbation of anxiety, no placebo-controlled studies have been conducted in de novo PD patients in order to adequately determine its effects.

Collectively, these findings suggest that the effects of chronic L-DOPA on affective symptoms of PD are limited and that pharmacotherapy may even aggravate them. However, no blinded, placebo-controlled studies on the effects of DA replacement therapy on anxiety and depression have been completed in de novo patients to date. This is likely due to ethical constraints and highlights the need for preclinical models of the affective symptoms in PD.

4. Animal models of depression and anxiety symptoms in PD

There are several neurotoxin-related animal models of PD which mimic the nigrostriatal DA cell loss characteristic of the disease process, including nigrostriatal lesions with the neurotoxin, 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), and peripheral injection of N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) or rotenone. Such models have been used extensively to investigate the motor symptoms of PD since the 1970s. For example, Tadaiesky and colleagues (2008) observed that partial, bilateral 6-OHDA lesions induced symptoms of depression and anxiety using several well established behavioral measures (depression: forced swim test, sucrose consumption; anxiety: elevated plus maze; see also Branchi et al., 2008). Though no studies have investigated the effects of MPTP administration in non-human primates on affect, MPTP-treated mice show profound increases in immobility in the tail-suspension test, a sensitive behavioral measure of depression-like symptoms (Mori et al., 2005; but see Vuckovic et al., 2008).

In addition, genetic mouse models have more recently been developed which address abnormalities associated with familial PD, including mutations in Parkin, PINK1, and DJ1. Though research on the affective symptoms induced within these models has been scarce, a few studies have reported anxiety and depression symptoms. For instance, Zhu and colleagues (2007) reported increased anxiety-like behavior in open field and light-dark box in Parkin null mice, though the effects on anxiety in a mouse model which overexpressed A53T synuclein were contradictory (George et al., 2008). In a novel vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2) deficient mouse model of PD, mice displayed enhanced anxiety and depression-like behaviors, which became more severe with advancing age (Taylor et al., 2009).

As in the human clinical literature, the effect of L-DOPA on affective symptoms is equally unclear in animal models. While chronic L-DOPA treatment in intact rats has been shown to increase immobility in the forced swim test (Borah & Mohanakumar, 2007), only two studies have attempted to address the effects of L-DOPA treatment on affective symptoms in animal models of PD. Winter and colleagues (2007) observed an increase in learned helplessness behaviors in rats following unilateral 6-OHDA lesions of the substantia nigra pars compacta, which was partially alleviated by acute L-DOPA treatment. In contrast, no benefits of chronic L-DOPA treatment in unilateral, 6-OHDA-lesioned rats were imbued in several measures of anxiety and depression in our laboratory, though mild anxiogenic effects of L-DOPA were detected (Eskow Jaunarajs et al., in press).

The utility of animal models to study affective disorders in PD is evident, since such research allows for precise control over L-DOPA dosage, DA depletion, genetic variability, and countless other variables that are a challenge to human PD research. However, an additional value of animal models is the multiple methods available to assess the behavioral, neurophysiological, and neurochemical effects of both DA cell loss and subsequent L-DOPA therapy. In fact, recent research using 6-OHDA-lesioned rats has hinted that L-DOPA treatment perturbs monoaminergic systems and could induce the development of affective disorders (Eskow Jaunarajs et al., in press; Navailles et al., 2010a, 2010b).

5. Possible monoaminergic mechanisms of anxiety and depression in PD

Traditionally, PD is thought of as a disorder associated with nigrostriatal DA cell loss and as such dopaminergic influences are more widely studied in the expression of affective disorders in PD. However, it is almost certain that dopaminergic depletion only hints at the collective monoaminergic dysfunction that is evident in the Parkinsonian brain. According to Braak staging of PD pathology, NE dysfunction likely occurs prior to significant degradation of DA neurons (Braak et al., 2004). Serotonergic cell loss in the raphe nuclei is also evident prior to nigral DA neuron death (Braak et al., 2004; del Tredici et al., 2002). Furthermore, recent research suggests that the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems may play a more significant role in the manifestation of PD-related anxiety and depression than previously thought.

5.1. Dopamine

Several studies have noted that the onset of affective disorders predates the emergence of Parkinsonian motor symptoms in a subset of PD patients (Nilsson et al., 2001; Schuurman et al., 2002) and in preclinical animal models of PD (Branchi et al., 2008; Mori et al., 2005; Tadaiesky et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2009). Since motor symptoms typically do not manifest until ~70% of nigral DA neurons have been lost, affective behaviors may be more sensitive to such depletion. Furthermore, DA has been linked to the development and treatment of affective disorders in the general population and in animal models of depression and anxiety (Chen & Skolnick, 2007; Dunlop & Nemeroff, 2007). Thus, anxiety and depression may be linked to the progressive loss of DA neurons that is the cardinal feature of PD pathophysiology. Indeed, Remy and colleagues (2005) found an association between decreased binding to DA transporters in the left ventral striatum and depressive and anxious symptoms (see also Weintraub et al., 2004). In corroboration, nigral neuronal loss was 7 times greater in postmortem brains of PD patients with depression compared to non-depressed PD patients (Frisina et al., 2009), suggesting that depression may be the result of more severe DA-depletion.

If the enhanced prevalence of affective disorders in PD were solely due to DA cell loss, DA replacement therapy with L-DOPA should reliably reduce anxiety and depression. However, de novo patients exposed to L-DOPA have not shown consistent improvement despite substantial reductions in the motor symptoms of PD (Choi et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2009), as described previously. Furthermore, DA-depleted rats expressed enhanced learned helplessness behaviors that were only partially alleviated by DA replacement therapy with L-DOPA (Winter et al., 2007). The inability of L-DOPA treatment to reliably improve affect may be associated with the supraphysiological release of DA into brain regions related to affect, such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, as observed by Navailles and colleagues (2010a) in unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Supraphysiological release of DA is purported as a trigger for psychosis and agitation, which may contribute to anxiety and depression in PD patients. These findings suggest that DA depletion may induce a susceptibility to affective disorders, but does not fully account for the onset of anxiety and depression in PD.

5.2. Norepinephrine

The NE system has been implicated in the expression of affective disorders and evidence for their involvement stems predominantly from the effectiveness of compounds that enhance NE release (Delgado & Moreno, 2000; Ressler & Nemeroff, 2000). In fact, noradrenergic antidepressants, such as nortriptyline have recently proven to be more effective than selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors in PD patients with depression (SSRIs; Menza et al., 2009), and may suggest a more prominent role for NE. In support, the NE system is certainly affected by the disease process, as evidenced by the profound loss of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus that occurs prior to DA cell loss within the substantia nigra (Braak et al., 2004; Frisina et al., 2009). Due to NE loss, significant changes in the expression of NE receptors and transporters may prompt the development or exacerbation of anxiety. For example, PD patients exhibit susceptibility to panic attacks induced by yohimbine, an α2-adrenergic antagonist, similar to those in psychiatric patients with panic disorder (Richard et al., 1999). Furthermore, lower DA/NE transporter binding in the locus coeruleus is correlated with increased incidence of anxiety and depression in PD patients (Remy et al., 2005). While plasma NE is actually elevated in de novo PD patients (Ahlskog et al., 1996), lower levels of dopamine β-hydroxylase, the enzyme responsible for hydroxylation of DA to NE, have been observed in the cerebrospinal fluid of L-DOPA-treated PD patients (Nagatsu & Sawada, 2007; O'Connor et al., 1994) and imply that L-DOPA treatment may alter NE levels.

NE levels should intuitively increase upon DA replacement therapy with L-DOPA as NE is catabolized from DA via dopamine β-hydroxylase. However, acute L-DOPA treatment does not appear to bolster NE levels (Chia et al., 1993; Everett & Borcherding, 1970). In fact, Nicholas and colleagues (2008) reported that NE levels in the striatum and olfactory bulb were reduced upon L-DOPA administration in MPTP-treated mice. These findings were recently corroborated in a unilateral, 6-OHDA-lesioned rat model of PD where we reported reduced tissue NE levels in the striatum, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Eskow Jaunarajs et al., in press).

A possible mechanism underlying these effects has been suggested through studies which propose that DA is co-released with NE (Devoto et al., 2005, 2008). Indeed, DA levels are enhanced approximately 5-fold, while NE is almost undetectable in human cases of congenital dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency (Man in `t Veld et al., 1988; Timmers et al., 2004). Following DA cell loss, studies have shown that L-DOPA is converted to DA within noradrenergic neurons and released into forebrain areas (Arai et al., 2008; Nishi et al., 1991). While beneficial to movement and other DA-related functions, L-DOPA-induced DA release from NE terminals may usurp NE release, leading to a paucity of this crucial neurotransmitter at traditionally noradrenergic synapses. In support, Vardi and colleagues (1979) observed that L-DOPA administration to PD patients resulted in significant reductions in dopamine β-hydroxylase activity. However, future studies are necessary to determine the exact mechanism of L-DOPA's interference with dopamine β-hydroxylase and other aspects of NE function.

5.3. Serotonin

The 5-HT system has been the focus of a large proportion of research on affective disorders and is also affected by the PD process in most patients (Albin et al., 2008; Guttman et al., 2007; Halliday et al., 1990a,b; Kish et al., 2008) and in some animal models of PD (Nayyar et al., 2009; Ren & Feng, 2007; Vuckovic et al., 2008). However, in a recent neuroanatomical study, Frisina and colleagues (2008) found neuronal loss and gliosis in the substantia nigra pars compacta and locus coeruleus of PD patients with depression but did not observe any pathophysiology in the raphe nuclei, the densest region of 5-HT neurons within the brain. Moreover, acute tryptophan depletion in a small group of human PD patients has not been shown to exacerbate or induce depression or anxiety (Leentjens et al., 2006). In contrast, others have observed increased pathology in the raphe of depressed compared to non-depressed PD patients (Becker et al., 1997; Paulus & Jellinger, 1991). Tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) activity and tetrahydrobiopterin, a necessary cofactor for 5-HT catabolism, are also reduced (Nagatsu et al., 1981; Sawada et al., 1985; Yamaguchi et al., 1983) and levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), a metabolite of 5-HT, were found to be lower in the cerebrospinal fluid of depressed PD patients in several studies (Kostic et al., 1987; Mayeux et al., 1984, 1986). Conversely, these effects were not observed in depressed “de novo” patients that had not yet begun DA replacement therapy with L-DOPA, suggesting that treatment or disease progression may somehow lead to a reduction in 5-HT release (Kuhn et al., 1996).

Like NE, L-DOPA treatment has been implicated in 5-HT dysfunction. In intact rats, Borah and Mohanakumar (2007) observed that DA and its metabolites were increased at the expense of reduced 5-HT release in the dorsal raphe nucleus, striatum, and prefrontal cortex after 60 days of L-DOPA administration. This effect appears to hold true in the parkinsonian brain. Maruyama and colleagues (1992) observed a significant reduction in 5-HT metabolism (reduced 5-HIAA/TPH ratio) in PD patients and DA-depleted rats receiving L-DOPA treatment. Other preclinical investigations have maintained that rats chronically treated with L-DOPA show reduced striatal and amygdalar 5-HT and 5-HIAA levels (Carta et al., 2007; Eskow Jaunarajs et al., in press). These results were recently bolstered by studies with in vivo microdialysis by Navailles and colleagues (2010a) as significant dose-dependent reductions in 5-HT release within the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex ipsilateral to the lesion were observed following acute L-DOPA treatments in anaesthetized, hemiparkinsonian rats.

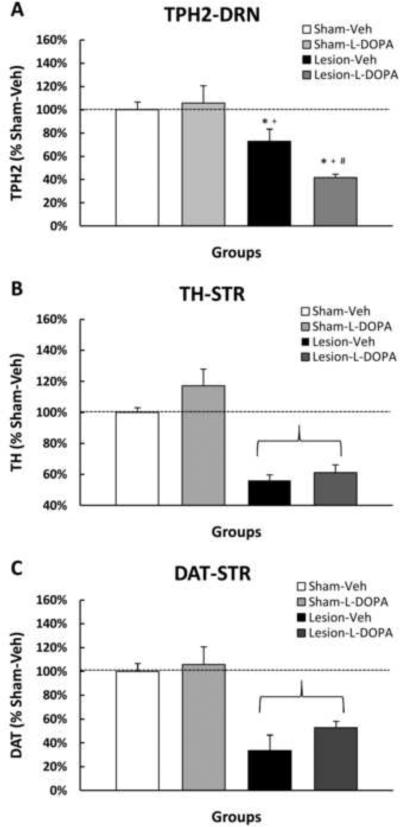

The mechanistic link between L-DOPA administration and 5-HT dysfunction has yet to be discerned, though there are several possibilites. First, L-DOPA may be competing with the serotonin precursor, 5-hydroxytryptophan for conversion via AADC. However, no reports have suggested that this enzyme is rate-limiting. Second, L-DOPA may inhibit tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH; Hashiguti et al., 1993). Since DRN 5-HT neurons lack the protective antioxidant mechanisms of SNpc DA neurons, they may be more vulnerable to interference from byproducts of L-DOPA/DA synthesis and metabolism, such as quinones formed from L-DOPA or DA. In support, Kuhn and Arthur (1998, 1999) found that in vitro exposure of TPH to L-DOPA-quinones results in inactivation of the catalytic core of the TPH enzyme, substantially reducing 5-HT catabolism. We recently demonstrated that chronic L-DOPA for 8 weeks resulted in a marked reduction in TPH expression within the dorsal raphe nucleus in rats lesioned bilaterally with 6-OHDA (Figure 1A), despite no difference in the extent of the DA-lesion measured by TH and dopamine transporter (DAT) versus vehicle-treated rats (Figure 1B). Finally, much like the NE system, 5-HT neurons may also act as surrogates for the DA system following severe DA loss by taking up exogenous L-DOPA, converting it to DA, and releasing it in forebrain areas at the expense of their normal serotonergic function. For example, NE and 5-HT fibers form functional synapses that have been shown to take up exogenously administered L-DOPA and convert and release L-DOPA-derived DA into the striatum as a “false neurotransmitter” (Arai et al., 2008; Carta et al., 2007; Eskow et al., 2009; Kannari et al., 2001; Ng et al., 1970). This phenotypic alteration has been suggested to result in reductions in 5-HT following L-DOPA treatment in hemiparkinsonian rats (Carta et al., 2008; Navailles et al., 2010a, 2010b). Such inhibition could be the driving force behind changes in 5-HT neuronal function following chronic L-DOPA treatment, which may spur development of affective symptoms.

Figure 1.

Effect of bilateral, intracerebroventricular 6-OHDA lesion and subsequent L-DOPA treatment on A) tryptophan hydroxylase-2 (TPH-2), and B) tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and C) dopamine transporter (DAT) expression in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) and striatum, respectively. Animals were injected bilaterally with either vehicle (0.1% ascorbic acid in 0.9% NaCl) or 6-OHDA (200 μg in 10 μL) into the lateral ventricles. Three weeks later, rats received either Vehicle (0.1% ascorbic acid in 0.9% NaCl) or L-DOPA methyl ester (12 mg/kg + benserazide, 15 mg/kg, sc) once daily for approximately 75 days resulting in 4 groups: Sham-VEH, Sham-L-DOPA, Lesion-VEH, Lesion-L-DOPA. Rats were killed 1 h after their last treatment and the DRN and striatum were microdissected and flash-frozen for Western blot analysis of TPH-2 and TH, respectively. Bars represent percentage of TPH-2, TH, and DAT expression versus Sham-VEH (100%) + SE (n=4–6/group). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of 6-OHDA lesion (TPH-2: F1,14=29.40, p<0.05; TH: F1,14=73.27,  p<0.05; DAT: F1,14=39.90,

p<0.05; DAT: F1,14=39.90,  p<0.05) and a lesion by treatment interaction (TPH-2: F1,14=4.78, p<0.05). Significant differences between groups were determined via LSD post hoc comparisons (*p<0.05 vs. Sham-VEH, +p<0.05 vs. Sham-LD, #p<0.05 vs. Lesion-VEH).

p<0.05) and a lesion by treatment interaction (TPH-2: F1,14=4.78, p<0.05). Significant differences between groups were determined via LSD post hoc comparisons (*p<0.05 vs. Sham-VEH, +p<0.05 vs. Sham-LD, #p<0.05 vs. Lesion-VEH).

6. Conclusion

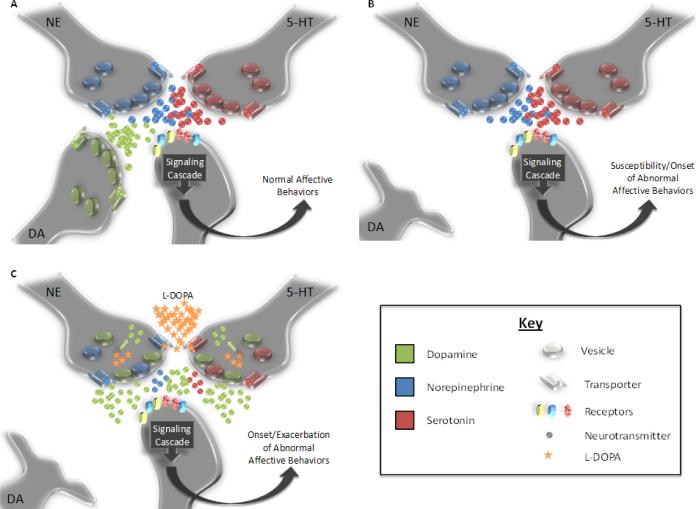

A number of unconfirmed hypotheses exist for the neural correlates of affective disorders in PD. Depletion of NE and 5-HT levels as the neurons are appropriated by dopaminergic processes could explain the worsening or development of anxiety and depression observed in PD patients undergoing chronic DA replacement therapy (Figure 2), as well as other non-motor symptoms including sleep disturbances, cognitive deficit and autonomic dysfunction. DA release from non-dopaminergic neurons may also be unregulated by appropriate autoreceptor mechanisms and may lead to the expression of other complications of L-DOPA treatment, including L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia (de la Fuente-Fernandez et al., 2004; Jenner, 2008), compulsions (Voon & Fox, 2007), and psychosis (Fenelon et al., 2008). Though it may be difficult to directly test in human patients, several distinct animal models for PD exist that could potentially address these questions. However, these methods have only recently been employed to explore the psychiatric effects of both DA depletion and subsequent L-DOPA treatment and more investigation is essential. In all, discovering the mechanisms behind affective complications in PD may be an exciting new avenue for researchers. Furthermore, additional depiction of these mechanisms in the compromised brain may extend their application to the underlying origin of affective disorders in the general population.

Figure 2.

Representation of possible effects of PD and subsequent L-DOPA treatment on the forebrain monoaminergic synapses. A) In the normal brain, balance is maintained between NE, 5-HT, and DA release among forebrain post-synaptic neurons that ensures normal affective behaviors. B) Following the loss of SNc neurons, DA loss modifies synaptic neurotransmission and may induce either the onset or a susceptibility to affective disorders. C) While exogenous L-DOPA treatment replaces DA within the synapse, it may supplant non-dopaminergic neurotransmission. For example, 5-HT and NE neurons take up L-DOPA via their respective transporters, convert it to DA via AADC, and release it in forebrain regions following DA depletion (Arai et al., 2008; Kannari et al., 2001). Such mechanisms have preliminarily been shown to usurp NE and/or 5-HT function (Eskow Jaunarajs et al., in press; Navailles et al., 2010a, 2010b). The reduction in 5-HT and NE function may portend the onset or exacerbation of anxiety and depression in PD patients undergoing L-DOPA treatment.

Research Highlights.

Parkinson's disease patients have high incidences of affective disorders

L-DOPA treatment does not reliably improve affective symptoms

L-DOPA is taken up by NE and 5-HT neurons and released as a false neurotransmitter

L-DOPA may worsen or induce anxiety and depression by perturbing NE and 5-HT systems

Table 2.

Investigations of effects of DA depletion and L-DOPA treatment on anxiety and depression symptoms in animal models of Parkinson's disease.

| Reference | Species | PD model | L-DOPA dosea | Treatment Length | Behavioral Tests | Effect of Model | Effect of L-DOPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tadaiesky et al., 2008 (see also Branchi et al., 2008) | Rat | Striatal 6-OHDA (bilateral) | -- | -- | Elevated Plus Maze | Anxiogenic | -- |

| Forced Swim Test | Depressogenic | -- | |||||

| Sucrose Consumption | Depressogenic | -- | |||||

| Vuckovic et al., 2008 | Mouse | MPTP | -- | -- | Tail Suspension Test | No effect | -- |

| Sucrose Preference | No effect | -- | |||||

| Light-Dark Box | No effect | -- | |||||

| Hole-Board Test | No effect | -- | |||||

| Zhu et al., 2007 | Mouse | Parkin null | -- | -- | Open Field | Anxiogenic | -- |

| Light-Dark Box | Anxiogenic | -- | |||||

| George et al., 2008 | Mouse | A53T synuclein trangenic | -- | -- | Elevated Plus Maze | Anxiolytic | -- |

| Open Field | Anxiogenic | -- | |||||

| Taylor et al., 2009 | Mouse | VMAT-2 deficiency | -- | -- | Forced Swim Test | Depressogenic | -- |

| Tail Suspension Test | Depressogenic | -- | |||||

| Elevated Plus Maze | Anxiogenic | -- | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Mori et al., 2005 | Mouse | MPTP | 30/100 | Acute | Tail Suspension Test | Depressogenic | Antidepressant |

| Borah & Mohanakumar, 2007 | Rat | -- | 250 | 60 days | Forced Swim Test | -- | Depressogenic |

| Winter et al., 2007 | Rat | SNpc 6-OHDA (unilateral) | 25 | 3 days | Learned Helplessness | Depressogenic | Antidepressant |

| Eskow Jaunarajs et al., 2010 | Rat | MFB 6-OHDA (unilateral) | 12 | 75 days | Locomotor Chambers | Anxiogenic | Anxiogenic |

| Forced Swim Test | Depressogenic | No effect | |||||

| Social Interaction | Anxiogenic | Anxiogenic | |||||

| Sucrose Consumption | No effect | No effect | |||||

mg/kg/day

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kristin B. Dupre and Dr. Terrence Deak for their helpful discussion.

Supported by NINDS grant NIH NS059600 (CB) and the Center for Development and Behavioral Neuroscience at Binghamton University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarsland D, Brønnick K, Alves G, Tysnes OB, Pedersen KF, Ehrt U, Larsen JP. The spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with early untreated Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2009;80:928–30. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.166959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlskog JE, Uitti RJ, Tyce GM, O'Brien JF, Petersen RC, Kokmen E. Plasma catechols and monoamine oxidase metabolites in untreated Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. J. Neurol. Sci. 1996;136:162–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00318-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Bohnen NI, Wernette K, Kilbourn MA, Frey KA. Spared caudal brainstem SERT binding in early Parkinson's disease. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow Metab. 2008;28:441–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabia G, Grossardt BR, Geda YE, Carlin JM, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Maraganore DM, Rocca WA. Increased risk of depressive and anxiety disorders in relatives of patients with Parkinson disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:1385–92. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai A, Tomiyama M, Kannari K, Kimura T, Suzuki C, Watanabe M, Kawarabayashi T, Shen H, Shoji M. Reuptake of L-DOPA-derived extracellular DA in the striatum of a rodent model of Parkinson's disease via norepinephrine transporter. Synapse. 2008;62:632–5. doi: 10.1002/syn.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T, Becker G, Seufert J, Hofmann E, Lange KW, Naumann M, Lindner A, Reichmann H, Riederer P, Beckmann H, Reiners K. Parkinson's disease and depression: evidence for an alteration of the basal limbic system detected by transcranial sonography. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1997;63:590–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.5.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1999;174:307–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah A, Mohanakumar KP. Long-term L-DOPA treatment causes indiscriminate increase in dopamine levels at the cost of serotonin synthesis in discrete brain regions of rats. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2007;27:985–96. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9213-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson's disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:121–34. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchi I, D'Andrea I, Armida M, Cassano T, Pèzzola A, Potenza RL, Morgese MG, Popoli P, Alleva E. Nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson's disease: investigating early-phase onset of behavioral dysfunction in the 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rat model. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:2050–61. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DJ, Doder M. Depression in Parkinson's disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2001;14:465–70. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantello R, Gilli M, Riccio A, Bergamasco B. Mood changes associated with “end-of-dose deterioration” in Parkinson's disease: a controlled study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1986;49:1182–90. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.10.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal FJ, Ziomkowski S, Mourão Mesquita H, Martínez-Martin P. Anxiety and depression: main determinants of health-related quality of life in Brazilian patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2008;14:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta M, Carlsson T, Kirik D, Björklund A. Dopamine released from 5-HT terminals is the cause of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in parkinsonian rats. Brain. 2007;130:1819–33. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta M, Carlsson T, Muñoz A, Kirik D, Björklund A. Involvement of the serotonin system in L-dopa-induced dyskinesias. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2008;14:S154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Skolnick P. Triple uptake inhibitors: therapeutic potential in depression and beyond. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2007;16:1365–77. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.9.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia LG, Cheng FC, Kuo JS. Monoamines and their metabolites in plasma and lumbar cerebrospinal fluid of Chinese patients with Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1993;116:125–34. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90316-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C, Sohn YH, Lee JH, Kim J. The effect of long-term levodopa therapy on depression level in de novo patients with Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000;172:12–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Sullivan M, Bowen JD, Kraft GH. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1862–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, 3rd, Vialou V, Nestler EJ. From synapse to nucleus: novel targets for treating depression. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR, Lobo-Antunes J, Macedo C. Psychiatric aspects in Parkinsonism treated with L-DOPA. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat. 1971;34:502–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.34.5.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Fernández R, Sossi V, Huang Z, Furtado S, Lu JQ, Calne DB, Ruth TJ, Stoessl AJ. Levodopa-induced changes in synaptic dopamine levels increase with progression of Parkinson's disease: implications for dyskinesias. Brain. 2004;127:2747–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Moreno FA. Role of norepinephrine in depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 1):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Tredici K, Rüb U, De Vos RA, Bohl JR, Braak H. Where does parkinson disease pathology begin in the brain? J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2002;61:413–26. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto P, Flore G, Saba P, Castelli MP, Piras AP, Luesu W, Viaggi MC, Ennas MG, Gessa GL. 6-Hydroxydopamine lesion in the ventral tegmental area fails to reduce extracellular dopamine in the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:1647–58. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto P, Flore G, Saba P, Fà M, Gessa GL. Stimulation of the locus coeruleus elicits noradrenaline and dopamine release in the medial prefrontal and parietal cortex. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:368–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:327–37. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskow KL, Dupre KB, Barnum CJ, Dickinson SO, Park JY, Bishop C. The role of the dorsal raphe nucleus in the development, expression, and treatment of L-dopa-induced dyskinesia in hemiparkinsonian rats. Synapse. 2009;63:610–20. doi: 10.1002/syn.20630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskow Jaunarajs KL, Dupre KB, Ostock CO, Button T, Deak T, Bishop C. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of chronic L-DOPA treatment on non-motor sequelae in the hemiparkinsonian rat. Behav. Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833e7e80. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett GM, Borcherding JW. L-Dopa: Effect on Concentrations of Dopamine, Norepinephrine, and Serotonin in Brains of Mice. Science. 1970;168:849–850. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3933.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fénelon G. Psychosis in Parkinson's disease: phenomenology, frequency, risk factors, and current understanding of pathophysiologic mechanisms. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:S18–25. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900017284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina PG, Haroutunian V, Libow LS. The neuropathological basis for depression in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2009;15:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funkiewiez A, Ardouin C, Cools R, Krack P, Fraix V, Batir A, Chabardès S, Benabid AL, Robbins TW, Pollak P. Effects of levodopa and subthalamic nucleus stimulation on cognitive and affective functioning in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2006;21:1656–62. doi: 10.1002/mds.21029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growdon JH, Kieburtz K, McDermott MP, Panisset M, Friedman JH. Levodopa improves motor function without impairing cognition in mild non-demented Parkinson's disease patients. Parkinson Study Group. Neurology. 1998;50:1327–31. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard BP, El Mansari M, Merali Z, Blier P. Functional interactions between dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine neurons: an in-vivo electrophysiological study in rats with monoaminergic lesions. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:625–39. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Boileau I, Warsh J, Saint-Cyr JA, Ginovart N, McCluskey T, Houle S, Wilson A, Mundo E, Rusjan P, Meyer J, Kish SJ. Brain serotonin transporter binding in non-depressed patients with Parkinson's disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007;14:523–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday GM, Li YW, Blumbergs PC, Joh TH, Cotton RG, Howe PR, Blessing WW, Geffen LB. Neuropathology of immunohistochemically identified brainstem neurons in Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1990a;27:373–85. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday GM, Blumbergs PC, Cotton RG, Blessing WW, Geffen LB. Loss of brainstem serotonin- and substance P-containing neurons in Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 1990b;510:104–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90733-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantz P, Caradoc-Davies G, Caradoc-Davies T, Weatherall M, Dixon G. Depression in Parkinson's disease. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;151:1010–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe S, Schrödl B, Faltl M, Müller C, Auff E, Zeitlhofer J. Sleep disorders and depression in patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2001;104:275–80. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguti H, Nakahara D, Maruyama W, Naoi M, Ikeda T. Simultaneous determination of in vivo hydroxylation of tyrosine and tryptophan in rat striatum by microdialysis-HPLC: relationship between dopamine and serotonin biosynthesis. J. Neural Transm. Gen. Sect. 1993;93:213–23. doi: 10.1007/BF01244998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber SJ, Paulson GW, Shuttleworth EC. Relationship of motor symptoms, intellectual impairment, and depression in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1988;51:855–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. Molecular mechanisms of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:665–77. doi: 10.1038/nrn2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannari K, Yamato H, Shen H, Tomiyama M, Suda T, Matsunaga M. Activation of 5-HT(1A) but not 5-HT(1B) receptors attenuates an increase in extracellular dopamine derived from exogenously administered L-DOPA in the striatum with nigrostriatal denervation. J. Neurochem. 2001;76:1346–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Park SY, Cho YJ, Hong KS, Cho JY, Seo SY, Lee DH, Jeon BS. Nonmotor symptoms in de novo Parkinson disease before and after dopaminergic treatment. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009;287:200–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318:876–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostić VS, Djuricić BM, Covicković-Sternić N, Bumbasirević L, Nikolić M, Mrsulja BB. Depression and Parkinson's disease: possible role of serotonergic mechanisms. J. Neurol. 1987;234:94–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00314109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn DM, Arthur R., Jr. Dopamine inactivates tryptophan hydroxylase and forms a redox-cycling quinoprotein: possible endogenous toxin to serotonin neurons. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:7111–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07111.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn DM, Arthur RE., Jr. L-DOPA-quinone inactivates tryptophan hydroxylase and converts the enzyme to a redox-cycling quinoprotein. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1999;73:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn W, Müller T, Gerlach M, Sofic E, Fuchs G, Heye N, Prautsch R, Przuntek H. Depression in Parkinson's disease: biogenic amines in CSF of “de novo” patients. J. Neural Transm. 1996;103:1441–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01271258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulisevsky J, Pagonabarraga J, Pascual-Sedano B, García-Sánchez C, Gironell A, Trapecio Group Study Prevalence and correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson's disease without dementia. Mov. Disord. 2008;23:1889–96. doi: 10.1002/mds.22246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach EC, Duvoisin RC. Anxiety disorders in familial parkinsonism. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1991;148:274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach EC, Freeman A, Vogel RL. Differential DSM-III psychiatric disorder prevalence profiles in dystonia and Parkinson's disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004;16:29–36. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leentjens AF, Scholtissen B, Vreeling FW, Verhey FR. The serotonergic hypothesis for depression in Parkinson's disease: an experimental approach. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1009–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke MR. Depressive symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2008;15:21–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man in 't Veld A, Boomsma F, Lenders J, vd Meiracker A, Julien C, Tulen J, Moleman P, Thien T, Lamberts S, Schalekamp M. Patients with congenital dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency. A lesson in catecholamine physiology. Am. J. Hypertens. 1988;1:231–8. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricle RA, Nutt JG, Valentine RJ, Carter JH. Dose-response relationship of levodopa with mood and anxiety in fluctuating Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 1995;45:1757–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.9.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh GG, Markham CH. Does levodopa alter depression and psychopathology in Parkinsonism patients? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1973;36:925–35. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.6.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama W, Naoi M, Takahashi A, Watanabe H, Konagaya Y, Mokuno K, Hasegawa S, Nakahara D. The mechanism of perturbation in monoamine metabolism by L-dopa therapy: in vivo and in vitro studies. J. Neural. Transm. Gen. Sect. 1992;90:183–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01250960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux R, Stern Y, Cote L, Williams JB. Altered serotonin metabolism in depressed patients with parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1984;34:642–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.5.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux R, Stern Y, Williams JB, Cote L, Frantz A, Dyrenfurth I. Clinical and biochemical features of depression in Parkinson's disease. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1986;143:756–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.6.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay A, Grace RC, Dalrymple-Alford JC, Anderson T, Fink J, Roger D. A profile of neuropsychiatric problems and their relationship to quality of life for Parkinson's disease patients without dementia. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2008;13:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menza M, Dobkin RD, Marin H, Mark MH, Gara M, Buyske S, Bienfait K, Dicke A. The impact of treatment of depression on quality of life, disability and relapse in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2009;24:1325–32. doi: 10.1002/mds.22586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondolo F, Jahanshahi M, Granà A, Biasutti E, Cacciatori E, Di Benedetto P. Evaluation of anxiety in Parkinson's disease with some commonly used rating scales. Neurol. Sci. 2007;28:270–5. doi: 10.1007/s10072-007-0834-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori A, Ohashi S, Nakai M, Moriizumi T, Mitsumoto Y. Neural mechanisms underlying motor dysfunction as detected by the tail suspension test in MPTP-treated C57BL/6 mice. Neurosci. Res. 2005;51:265–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T, Sawada M. Biochemistry of postmortem brains in Parkinson's disease: historical overview and future prospects. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2007;72:113–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-73574-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T, Yamaguchi T, Kato T, Sugimoto T, Matsuura S, Akino M, Nagatsu I, Iizuka R, Narabayashi H. Biopterin in human brain and urine from controls and parkinsonian patients: application of a new radioimmunoassay. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1981;109:305–11. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(81)90316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navailles S, Benazzouz A, Bioulac B, Gross C, De Deurwaerdère P. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus and L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine inhibit in vivo serotonin release in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2010a;30:2356–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5031-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navailles S, Bioulac B, Gross C, De Deurwaerdère P. Serotonergic neurons mediate ectopic release of dopamine induced by l-DOPA in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010b;38:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayyar T, Bubser M, Ferguson MC, Neely MD, Shawn Goodwin J, Montine TJ, Deutch AY, Ansah TA. Cortical serotonin and norepinephrine denervation in parkinsonism: preferential loss of the beaded serotonin innervation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;30:207–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nègre-Pagès L, Grandjean H, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL, Fourrier A, Lépine JP, Rascol O, DoPaMiP Study Group Anxious and depressive symptoms in Parkinson's disease: the French cross-sectionnal DoPaMiP study. Mov. Disord. 2010;25:157–66. doi: 10.1002/mds.22760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng KY, Chase TN, Colburn RW, Kopin IJ. L-Dopa-induced release of cerebral monoamines. Science. 1970;170:76–7. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3953.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson FM, Kessing LV, Bolwig TG. Increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease for patients with major affective disorder: a register study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001;104:380–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissenbaum H, Quinn NP, Brown RG, Toone B, Gotham AM, Marsden CD. Mood swings associated with the `on-off' phenomenon in Parkinson's disease. Psychol. Med. 1987;17:899–904. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuti A, Ceravolo R, Piccinni A, Dell'Agnello G, Bellini G, Gambaccini G, Rossi C, Logi C, Dell'Osso L, Bonuccelli U. Psychiatric comorbidity in a population of Parkinson's disease patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2004;11:315–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DT, Cervenka JH, Stone RA, Levine GL, Parmer RJ, Franco-Bourland RE, Madrazo I, Langlais PJ, Robertson D, Biaggioni I. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase immunoreactivity in human cerebrospinal fluid: properties, relationship to central noradrenergic neuronal activity and variation in Parkinson's disease and congenital dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 1994;86:149–58. doi: 10.1042/cs0860149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pålhagen SE, Carlsson M, Curman E, Wålinder J, Granérus AK. Depressive illness in Parkinson's disease--indication of a more advanced and widespread neurodegenerative process? Acta Neurol. Scand. 2008;117:295–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus W, Jellinger K. The neuropathologic basis of different clinical subgroups of Parkinson's disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1991;50:743–55. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontone GM, Williams JR, Anderson KE, Chase G, Goldstein SA, Grill S, Hirsch ES, Lehmann S, Little JT, Margolis RL, Rabins PV, Weiss HD, Marsh L. Prevalence of anxiety disorders and anxiety subtypes in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2009;24:1333–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.22611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racette BA, Hartlein JM, Hershey T, Mink JW, Perlmutter JS, Black KJ. Clinical features and comorbidity of mood fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2002;14:438–42. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, Griffin HJ, Quinn NP, Jahanshahi M. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease: the relative importance of the symptoms. Mov. Disord. 2008;23:1428–34. doi: 10.1002/mds.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy P, Doder M, Lees A, Turjanski N, Brooks D. Depression in Parkinson's disease: loss of dopamine and noradrenaline innervation in the limbic system. Brain. 2005;128:1314–22. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Feng J. Rotenone selectively kills serotonergic neurons through a microtubule-dependent mechanism. J. Neurochem. 2007;103:303–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Nemeroff CB. Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2000. 2000;12:S2–19. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1+<2::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard IH, Frank S, McDermott MP, Wang H, Justus AW, Ladonna KA, Kurlan R. The ups and downs of Parkinson disease: a prospective study of mood and anxiety fluctuations. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2004;17:201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard IH, Schiffer RB, Kurlan R. Anxiety and Parkinson's disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1996;8:383–92. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard IH, Szegethy E, Lichter D, Schiffer RB, Kurlan R. Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study of yohimbine challenge in patients with anxiety. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1999;22:172–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo G, Vitale C, Trojano L, Longo K, Cozzolino A, Grossi D, Barone P. Relationship between depression and cognitive dysfunctions in Parkinson's disease without dementia. J. Neurol. 2009;256:632–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M, Nagatsu T, Nagatsu I, Ito K, Iizuka R, Kondo T, Narabayashi H. Tryptophan hydroxylase activity in the brains of controls and parkinsonian patients. J. Neural Transm. 1985;62:107–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01260420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag A. Quality of life and depression in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006;248:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman AG, van den Akker M, Ensinck KT, Metsemakers JF, Knottnerus JA, Leentjens AF, Buntinx F. Increased risk of Parkinson's disease after depression: a retrospective cohort study. Neurology. 2002;58:1501–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.10.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba M, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Peterson BJ, Ahlskog JE, Schaid DJ, Rocca WA. Anxiety disorders and depressive disorders preceding Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Mov. Disord. 2000;15:669–77. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200007)15:4<669::aid-mds1011>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemers ER, Shekhar A, Quaid K, Dickson H. Anxiety and motor performance in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 1993;8:501–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.870080415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy MA, Murck H, Kroenke K. Responsiveness of motor and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease to dopaminergic therapy. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;34:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein SE, Merello M, Jorge R, Brockman S, Bruce D, Petracca G, Robinson RG. A validation study of depressive syndromes in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2008;23:538–46. doi: 10.1002/mds.21866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein SE, Preziosi TJ, Forrester AW, Robinson RG. Specificity of affective and autonomic symptoms of depression in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1990;53:869–73. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.10.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Heuser IJ, Juncos JL, Uhde TW. Anxiety disorders in patients with Parkinson's disease. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1990;147:217–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Miyamoto M, Miyamoto T, Okuma Y, Hattori N, Kamei S, Yoshii F, Utsumi H, Iwasaki Y, Iijima M, Hirata K. Correlation between depressive symptoms and nocturnal disturbances in Japanese patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2008;15:15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadaiesky MT, Dombrowski PA, Figueiredo CP, Cargnin-Ferreira E, Da Cunha C, Takahashi RN. Emotional, cognitive and neurochemical alterations in a premotor stage model of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 2008;156:830–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Aarsland D, Cummings JL. The occurrence of depression in Parkinson's disease. A community-based study. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:175–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550020087019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TN, Caudle WM, Shepherd KR, Noorian A, Jackson CR, Iuvone PM, Weinshenker D, Greene JG, Miller GW. Nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease revealed in an animal model with reduced monoamine storage capacity. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:8103–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1495-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers HJ, Deinum J, Wevers RA, Lenders JW. Congenital dopamine-beta-hydroxylase deficiency in humans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1018:520–3. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi J, Flechter S, Oberman Z, Allelov M, Rabey JM, Hertzberg M, Streifler M. Plasma dopamine beta hydroxylase (D.B.H.) activity in Parkinsonian patients under L-dopa, and 2-bromo-alpha-ergocriptine loading. J. Neural Transm. 1979;46:71–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01243430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez A, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Garcia-Ruiz P, Garcia-Urra D. `Panic attacks' in Parkinson's disease. A long-term complication of levodopa therapy. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1993;87:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Fox SH. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviors in Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:1089–96. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucković MG, Wood RI, Holschneider DP, Abernathy A, Togasaki DM, Smith A, Petzinger GM, Jakowec MW. Memory, mood, dopamine, and serotonin in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse model of basal ganglia injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008;32:319–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Hong Z, Cheng Q, Xiao Q, Wang Y, Zhang J, Ma JF, Wang XJ, Zhou HY, Chen SD. Validation of the Chinese non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson's disease: results from a Chinese pilot study. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2009;111:523–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D, Moberg PJ, Duda JE, Katz IR, Stern MB. Recognition and treatment of depression in Parkinson's disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16:178–83. doi: 10.1177/0891988703256053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D, Moberg PJ, Duda JE, Katz IR, Stern MB. Effect of psychiatric and other nonmotor symptoms on disability in Parkinson's disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004;52:784–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D, Morales KH, Duda JE, Moberg PJ, Stern MB. Frequency and correlates of co-morbid psychosis and depression in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2006;12:427–31. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Chen H, Schwarzschild MA, Kawachi I, Ascherio A. Prospective study of phobic anxiety and risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2003;18:646–51. doi: 10.1002/mds.10425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, von Rumohr A, Mundt A, Petrus D, Klein J, Lee T, Morgenstern R, Kupsch A, Juckel G. Lesions of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and in the ventral tegmental area enhance depressive-like behavior in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;184:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt K, Daniels C, Herzog J, Lorenz D, Volkmann J, Reiff J, Mehdorn M, Deuschl G, Krack P. Differential effects of L-dopa and subthalamic stimulation on depressive symptoms and hedonic tone in Parkinson's disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006;18:397–401. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Wren PB. Serotonin-dopamine interactions: implications for the design of novel therapeutic agents for psychiatric disorders. Prog. Brain Res. 2008;172:213–30. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wragg RE, Jeste DV. Overview of depression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1989;146:577–87. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahr MD, Duvoisin RC, Schear MJ, Barrett RE, Hoehn MM. Treatment of parkinsonism with levodopa. Arch. Neurol. 1969;21:343–54. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480160015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Nagatsu T, Sugimoto T, Matsuura S, Kondo T, Iizuka R, Narabayashi H. Effects of tyrosine administration on serum biopterin in normal controls and patients with Parkinson's disease. Science. 1983;219:75–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6849120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemssen T, Reichmann H. Non-motor dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13:323–32. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]