Abstract

Background

Gait difficulty has been reported in essential tremor (ET) although it has been the subject of a limited number of studies. We broadly assessed these clinical correlates, including the association of gait difficulty with a variety of midline tremors (jaw, voice, neck).

Methods

Tandem gait (10 steps) was assessed in 122 ET cases. Cranial tremor score (0-3) was the number of locations (neck, jaw, voice) in which tremor was present.

Results

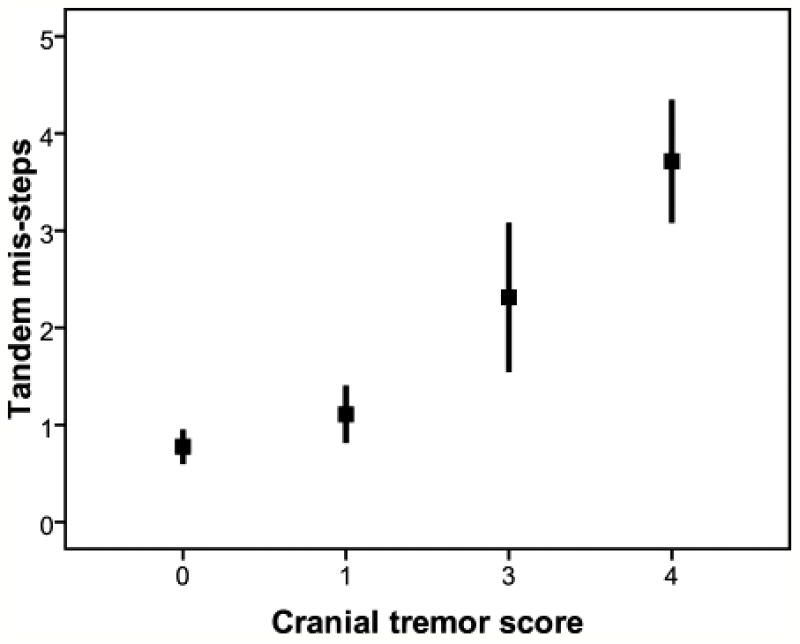

Number of tandem mis-steps positively correlated with age (p<0.001), age of tremor onset (p=0.001), and presence of neck (p<0.001), jaw (p=0.001), and voice tremors (p=0.047). Number of tandem mis-steps increased markedly with cranial tremor score: 0 (0.8±1.2), 1 (1.1±1.6), 2 (2.3±3.0), 3 (3.7±1.6) (p <0.001). It was not correlated with severity of arm or leg tremors.

Conclusions

ET patients with cranial tremors (neck, jaw, voice), those with older age of onset, and those of current older age are more likely to manifest tandem gait difficulty. Tandem gait difficulty was not correlated with severity of limb tremors. Tandem gait difficulty and cranial tremors in ET may both be symptomatic of the same underlying pathophysiology, a disturbance of cerebellar regulation of the midline, which is distinct from its regulation of the limbs.

Keywords: essential tremor, clinical correlate, gait, balance, ataxia, cerebellum, head tremor

Introduction

In recent years, gait and stance difficulties have been reported in patients with essential tremor (ET); these problems with equilibrium and postural control are in excess of those observed in similarly-aged control subjects.1-6 The mechanistic basis for this gait difficulty is not completely clear, although some evidence suggests that it reflects underlying cerebellar dysfunction.4, 7

Several1-5, 7 studies have examined a small handful of the possible clinical correlates of this gait difficulty (e.g., its association with tremor duration, tremor severity and age). Modest sample sizes (16,7 25,4, 5 30,2 36,1 and 603 patients), however, have limited the power of several of these studies to detect such correlates. Identifying these clinical correlates is important. First, these correlates might serve as clinical markers for ET patients who are at increased risk of disequilibrium and, possibly, falls. Second, the correlates themselves can provide novel insights into the mechanistic basis for the gait difficulty, which is not completely understood.

Curiously, two groups recently reported that ET patients with head (i.e., neck) tremor had more gait and balance difficulty than ET patients without such tremor;2, 6 however, two older studies had not observed this assocation.1, 3 While on the one hand, extra head motion itself could render balance more difficult,2 we hypothesize that the association between neck tremor and tandem gait difficulty in ET may be due to a shared pathophysiology, which is likely to be a disturbance of cerebellar regulation of the midline. Aside from neck tremor, tremors of other midline structures (jaw and voice) commonly occur in ET8-11 but these are not likely to make balance more difficult through extra head motion. To test our hypothesis, we predicted that ET patients with any midline tremor (jaw, voice, or neck) would have more tandem gait difficulty than ET patients without these tremors.

Our aims were, first, to broadly assess a full range of clinical correlates of tandem gait difficulty (N = 16 correlates) in a large sample of ET patients enrolled in an epidemiological study (N = 122 patients). Second, to use this sample to revisit the possible association between neck tremor and tandem mis-steps in ET and, further, to explore for the first time the associations between a variety of midline tremors (jaw, voice, neck) and tandem gait difficulty.

Methods

Subjects

Cases were enrolled in an ongoing (2000 – 2009) environmental epidemiological study of ET at the Neurological Institute of New York, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC),12 a tertiary referral center in northern Manhattan, New York. ET patients, age 18 and older, came from two primary sources: patients whose neurologist was on staff at the Institute or patients who were cared for by their local doctor in the tri-state region (New York, New Jersey, Connecticut) and, as members of the International Essential Tremor Foundation, had read advertisements for the study and volunteered. Prior to enrollment, all cases signed informed written consent approved by the CUMC Institutional Review Board. There are 122 cases, each of whom qualified for a diagnosis of ET using published diagnostic criteria (kinetic arm tremor rated ≥2 during at least 3 tests or head tremor)12 none of whom had PD or dystonia.

Evaluation

All cases underwent demographic and medical histories. Data on all current medications were collected and a Folstein Mini Mental Status Test (range = 0 – 30) was administered.13 In addition, a videotaped neurological examination was performed. This included one test for postural tremor and five for kinetic tremor (pouring, using spoon, drinking, finger-nose-finger, drawing spirals) performed with each arm (12 tests total). A neurologist specializing in movement disorders (E.D.L.) used a reliable 14 and validated 15 clinical rating scale, the Washington Heights-Inwood Genetic Study of ET (WHIGET) tremor rating scale, to rate postural and kinetic tremor during each test: 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe). These ratings resulted in a total tremor score (range = 0 – 36), which is an assessment of postural and kinetic tremor.12 In addition, the motor portion of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)16 was videotaped and rest tremor was rated (E.D.L.) using the videotaped motor portion of the UPDRS (ratings = 0 – 4).16 In our sample, all rest tremor ratings were low (0 or 1); hence, this was re-coded in the analyses as absent or present.

The finger-nose-finger maneuver included 10 repetitions per arm, and intention tremor was defined as present when tremor amplitude increased during visually guided movements towards the target.17 We excluded position-specific tremor or postural tremor at the end of movement. Intention tremor was rated (E.D.L.) in the terminal period of the finger-nose-finger test: 0 (no intention tremor); 0.5 (probable intention tremor); 1 (definite intention tremor); 2 (incapacitating intention tremor). The intention tremor score (both arms combined) ranged from 0 to 4. Cases with definite intention tremor in at least one arm or probable intention tremor in both arms were labeled as ET with intention tremor.17

On videotaped examination, jaw and voice tremors were coded as present or absent while cases were seated facing the camera. Jaw tremor was assessed while the mouth was stationary (closed), while the mouth was slightly open, during sustained phonation, and during speech.9 Voice tremor was assessed during sustained phonation, while reading a prepared paragraph, and during speech. Neck tremor in ET was coded as present or absent and was distinguished from dystonic tremor by the absence of twisting or tilting movements of the neck, jerk-like or sustained neck deviation, or hypertrophy of neck muscles; it was distinguished from titubation by its faster speed and the absence of accompanying truncal titubation or ataxia while seated or standing. A cranial tremor score (range = 0 – 3) was calculated for each subject based on the number of locations (neck, jaw, voice) in which tremor was present on examination.

A videotaped assessment of tandem gait was added in August, 2005. Tandem gait was explained and demonstrated to subjects. Each subject was asked to walk tandem (place one foot in front of the other touching toe to heel) and the number of missteps during 10-steps was counted.

During the videotaped tremor examination, kinetic tremor of the legs was assessed with subjects seated in a chair with footwear off during the big toe-to-examiner’s finger maneuver (10 repetitions per leg).18 Subjects fully extended the leg as the big toe approached and touched a fixed target 1.5 feet from the floor then returned the foot to the floor. Leg kinetic tremors were rated separately in each leg using a 0–3 scale: 0, no visible tremor; 0.5, questionably present; 1, low amplitude tremor; 1.5, intermittently moderate amplitude tremor (e.g., during <50% of repetitions); 2, consistently moderate amplitude tremor; and 3, large amplitude tremor. This resulted in a total kinetic leg tremor score (range = 0–6).18 Kinetic tremor was considered present if it received a score of 1 or higher in either leg.

Statistical Analyses

The number of tandem mis-steps was not normally distributed. Therefore, group comparisons used non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests). For linear regression models, we modified the tandem mis-step variable further. First, because in many cases, the number of tandem mis-steps was zero and the number of mis-steps was not normally distributed, we used the following value: log10 (tandem mis-steps + 1). Second, because age was such a strong predictor of the number of tandem mis-steps, we then divided this value by age: log10 (tandem mis-steps + 1)/age.

The clinical correlate of greatest a priori interest was the possible association between number of tandem mis-steps and presence of neck tremor. Power analysis indicated that, with our sample size, we had 88.2% power to detect a doubling of the number of tandem mis-steps in cases with vs. without neck tremor (assuming alpha = 0.05).

Results

Case Characteristics

There were 134 cases. Twelve (mean age = 77.1 ± 10.1 years; 6 [50.0%] with cranial tremor) were excluded because they were unable to attempt the tandem gait task (2 because of pain with ambulation, 1 because of arm and leg weakness after a stroke, and 9 who used canes). One hundred twenty two cases remained. The 122 cases had a mean age of 64.9 ± 15.4 years and 73 (59.8%) were men (Table 1). Approximately one-half of cases (n = 60, 49.2%) had neck, jaw or voice tremor (cranial tremor score ≥1) (Table 1). A similar proportion had one or more tandem mis-steps (n = 63, 51.6%). Twenty-two (18.0%) had 3 or more tandem mis-steps (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 122 ET cases

| Age (years) | 64.9 ± 15.4 |

| Male gender | 73 (59.8) |

| Education (years) | 16.0 ± 2.8 |

| Total tremor score | 18.1 ± 6.3 |

| Tremor duration (years) | 24.7 ± 19.4 |

| Age of tremor onset (years) | 40.5 ± 22.6 |

| Folstein Mini Mental Status Test score | 28.9 ± 1.3 |

| Currently takes a medication that is sedating or is an anticonvulsant | 30 (20.4%) |

| Family history of tremor (first or second degree relative) | 81 (66.4) |

| Neck tremor | 39 (32.0) |

| Jaw tremor | 13 (10.7) |

| Voice tremor | 38 (31.1) |

| Cranial tremor score | |

| 0 | 62 (50.8) |

| 1 | 37 (30.3) |

| 2 | 16 (13.1) |

| 3 | 7 (5.7) |

| Cranial tremor score | 0.7 ± 0.9 |

| Intention tremor | 48 (39.3) |

| Intention tremor score | 1.2 ± 1.3 |

| Rest tremor | 15 (12.3) |

| Kinetic leg tremor | 54 (44.3%) |

| Total kinetic leg tremor score | 1.5 ± 1.0 |

| Tandem mis-steps | |

| 0 | 59 (48.4) |

| 1 | 27 (22.1) |

| 2 | 14 (11.5) |

| 3 | 12 (9.8) |

| 4 | 1 (0.8) |

| 5 | 4 (3.3) |

| 6 | 2 (1.6) |

| 7 | 1 (0.8) |

| 8 | 1 (0.8) |

| 9 | 0 (0.0) |

| 10 | 1 (0.8) |

| Tandem mis-steps | 1.3 ± 1.8 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage).

Clinical Correlates of Tandem Mis-steps in ET

Clinical correlates of tandem gait difficulty are presented in Table 2. The number of tandem mis-steps increased with age (r = 0.61, p < 0.001) and age of tremor onset (r = 0.29, p = 0.001), was greater in women (p = 0.03), and was greater in cases with neck tremor (p < 0.001), jaw tremor (p = 0.001), and voice tremor (p = 0.047). The difference in number of tandem mis-steps between cases with vs. without intention tremor was not significant. The number of tandem mis-steps was not correlated with education or a number of important disease characteristics (total tremor score, tremor duration, presence of rest tremor, kinetic tremor of the legs) as well as other clinical characteristics (family history of tremor, Mini Mental Status Test score, use of sedating medications or anticonvulsants).

Table 2.

Clinical correlates of tandem mis-steps in 122 ET cases

| Age (years) | r = 0.61, p < 0.001 |

| Gender | |

| Men | 1.0 ± 1.7 |

| Women | 1.6 ± 2.0 |

| p = 0.03* | |

| Education (years) | r = -0.06, p = 0.55 |

| Total tremor score | r = 0.01, p = 0.89 |

| Tremor duration (years) | r = 0.13, p = 0.15 |

| Age of tremor onset (years) | r = 0.29, p = 0.001 |

| Folstein Mini Mental Status Test score | r = -0.09, p = 0.35 |

| Currently takes a medication that is sedating or is an anticonvulsant | |

| Yes | 1.4 ± 1.8 |

| No | 1.2 ± 1.8 |

| p = 0.22* | |

| Family history of tremor (first or second degree relative) | |

| Present | 1.3 ± 2.0 |

| Absent | 1.2 ± 1.4 |

| p = 0.46* | |

| Neck tremor | |

| Present | 2.1 ± 2.4 |

| Absent | 0.8 ± 1.3 |

| p < 0.001* | |

| Jaw tremor | |

| Present | 3.2 ± 2.8 |

| Absent | 1.0 ± 1.5 |

| p = 0.001* | |

| Voice tremor | |

| Present | 1.8 ± 2.1 |

| Absent | 1.0 ± 1.6 |

| p = 0.047* | |

| Cranial tremor score | |

| 0 | 0.8 ± 1.2 |

| 1 | 1.1 ± 1.6 |

| 2 | 2.3 ± 3.0 |

| 3 | 3.7 ± 1.6 |

| p < 0.001** | |

| Cranial tremor score | r = 0.32, p < 0.001 |

| Intention tremor | |

| Present | 1.4 ± 2.3 |

| Absent | 1.1 ± 1.4 |

| P = 0.91* | |

| Intention tremor score | r = -0.01, p = 0.96 |

| Rest tremor | |

| Present | 1.3 ± 1.8 |

| Absent | 1.3 ± 1.8 |

| p = 0.97* | |

| Kinetic Leg tremor | |

| Present | 1.5 ± 2.3 |

| Absent | 1.0 ± 1.4 |

| p = 0.51* | |

| Total kinetic leg tremor score | r = -0.04, p = 0.73 |

Column on right shows either the correlation between number of tandem mis-steps and each clinical characteristic (e.g., age) or the difference in number of tandem mis-steps between strata (e.g., men vs. women). All correlation coefficients are Spearman’s rho.

Mann-Whitney test.

Kruskal Wallis test

Neck, Jaw, and Voice Tremor and Tandem Mis-steps

In unadjusted analyses (above), the number of tandem mis-steps was increased in the presence of neck tremor, jaw tremor, or voice tremor (Table 2). In a linear regression model that adjusted for gender and age of tremor onset (each of which had been associated with number of tandem mis-steps in univariate analyses, Table 2), tandem mis-steps (i.e., log10 (tandem mis-steps + 1)/age) were associated with neck tremor (beta = 0.002, p = 0.002), age of tremor onset (beta = 0.00002, p < 0.001) but not gender (beta = 0.001, p = 0.23). In two similarly adjusted models, tandem mis-steps were associated with jaw tremor (beta = 0.004, p < 0.001) and with voice tremor (beta = 0.002, p = 0.026) as well as age of tremor onset and gender.

The absence of cranial tremor was associated with 0.8 ± 1.2 tandem mis-steps (Table 3). While the presence of neck tremor was associated with an increase in tandem mis-steps (1.3 ± 1.6, Table 3), the further addition of jaw or voice tremor was associated with an additional increase (2.5 ± 3.2, Table 3), and the presence of all three cranial tremors, was attended by the largest number of mis-steps (3.7 ± 1.6, Table 3)(p < 0.001). To more fully explore the additive effects of having several types of cranial tremors, we calculated the cranial tremor score. The number of tandem mis-steps increased with increasing cranial tremor score (0 [0.8±1.2], 1 [1.1±1.6], 2 [2.3±3.0], 3 [3.7±1.6][p<0.001], Figure 1 and Table 2) and was correlated with the cranial tremor score (r = 0.32, p <0.001, Table 2). If we included in our analyses the 9 cases who could not attempt the tandem gait task because they used a cane, and assumed that they would have had the maximum number of mis-steps (10), the results were similar (the number of tandem mis-steps increased with increasing cranial tremor score (0 [1.5±2.7], 1 [1.8±2.8], 2 [2.8±3.4], 3 [3.7±1.6][p=0.004]). In a linear regression analysis adjusted for age of tremor onset and gender, tandem mis-steps (i.e., log10 (tandem mis-steps + 1)/age) were associated with the cranial tremor score (beta = 0.001, p < 0.001) as well as age of tremor onset (beta = 0.00002, p < 0.001) but not gender (beta = 0.001, p = 0.16) in the 122 included cases.

Table 3.

Tandem mis-steps and cranial tremor

| No neck, jaw or voice tremor | 0.8 ± 1.2 |

| Neck tremor only | 1.3 ± 1.6 |

| Neck tremor + jaw or voice tremor | 2.5 ± 3.2 |

| Neck tremor + jaw tremor + voice tremor | 3.7 ± 1.6 |

| P < 0.001* |

Kruskal Wallis test

Figure 1.

The number of tandem mis-steps increased with increasing cranial tremor score. Each bar represents one standard error and each box represents the mean number of tandem mis-steps.

Discussion

Gait and balance difficulty have been described in ET patients19 but there are few data on the clinical correlates of this difficulty.1-5, 7 Prior studies have had modest sample sizes and they often report disparate results; none have had as their central focus the study of these clinical correlates. Using a clinical sample of 122 ET cases, we examined a sizable number of clinical and disease characteristics, and reported a number of factors (cranial tremors, older age of tremor onset, older age) that were associated with greater tandem gait difficulty in ET, and other pertinent factors, which were not (tremor severity in the arms and legs).

The presence of neck tremor has been shown to be a predictor of gait and balance difficulty in ET in two recent studies,2, 6 although not in two older studies.1, 3 Although it has been conjectured that extra head motion itself could render balance more difficult,2 we hypothesized that ET patients with any number of midline tremors, including those that are not likely to make balance more difficult through extra head motion (e.g., jaw and voice tremors), would have more tandem gait difficulty than ET patients without these tremors. Therefore, we extended prior analyses by examining different types of cranial tremors, including neck, voice and jaw tremors. Interestingly, tandem gait difficulty was greater in ET cases with each of these types of tremor. Furthermore, the presence of two of these cranial tremors was associated with three times the number of tandem mis-steps (2.3 vs. 0.8) and the presence of three of these cranial tremors, with a nearly five-fold increase (3.7 vs. 0.8).

In contrast to cranial tremor, there was no association between number of tandem mis-steps and severity of limb tremors, including total tremor score (a measure of postural and kinetic arm tremors), intention tremor score (a measure of intentional arm tremor), rest tremor (arms), or kinetic leg tremor score. Three prior studies found no correlation with limb tremor severity.1, 3, 6 One prior study found no correlation with intention tremor,6 although other studies have indicated that greater imbalance occurs in ET patients with intention tremor and other cerebellar signs.4, 5 No prior studies have examined rest tremor.

On a mechanistic level, the set of correlations we observed is consistent with the hypothesis that the association between tandem gait difficulty and cranial tremors (neck, jaw, voice) is not merely a function of simple mechanical factors (i.e., head motion rendering gait more difficult) but rather, indicative of a more profound biological connection (e.g., shared pathophysiology) between the two. This is likely to be a disturbance of cerebellar regulation of the midline, which is distinct from its regulation of the limbs. The midline cerebellar syndrome is, in its fully developed form, associated with severe imbalance and truncal ataxia (e.g., inability to sit or stand without being steadied). Affected are truncal or limb girdle muscles and activities that require the cooperation of homologous bilateral muscles. This involvement of the body’s midline may be the result of midline (vermal) cerebellar pathology but may also be the result of more widespread involvement of the posterior fossa, including the cerebellar hemispheres.20, 21 Hence, we are suggesting that in ET there may be a midline cerebellar syndrome, characterized by imbalance and cranial tremors, which may accompany a cerebellar extremity syndrome that is characterized by kinetic and intentional tremors of the limbs (esp. arms). Whether the anatomic pathology of these two syndromes differs remains unexplored.

A novel observation was that cases with older age of tremor onset had more tandem mis-steps, even accounting for current age. A recent study noted differences between ET cases based on age of onset, noting that cases with older age of tremor onset had faster rates of tremor progression as well as more degenerative pathology in the cerebellum.22 These data raise the possibility that, as in several progressive neurological disorders,23-26 in older onset cases, the disease advances more rapidly and may be more malignant.

The association in ET between age and tandem mis-steps has been reported in two prior studies and is not surprising given the observation that imbalance tends to increase with age in general.1, 3 Although in initial analyses, we observed that women had more tandem mis-steps than men, multivariate models indicated that this was due to the increased preponderance of cranial tremors in women. Two prior studies similarly found no association between tandem mis-steps and gender.1, 3

This study had limitations. We examined the number of tandem mis-steps and did not examine postural sway or tandem gait on a treadmill. Yet even with this relatively limited clinical assessment, we were able to detect significant associations. Although cases underwent medical histories and videotaped neurological examinations, we cannot exclude the possibility that the presence of certain co-morbidities (e.g., neuropathy, myelopathy, or hydrocephalus) could have further impaired gait. Nonetheless, it is not likely to the presence of such co-morbidities was responsible for the observed association between cranial tremor and tandem mis-steps. Strengths of this study included the large sample of patients (N = 122), the examination of a large number of clinical correlates, and the separation of cranial tremor into different types and the examination of their additive effects.

What is the clinical significance of these findings? We have identified several markers for tandem gait difficulty and, possibly falls, in ET. Data indicate that recent falls (i.e., in the past year) are reported to occur in nearly one-third of ET cases, and recent near-misses, in more than one-half of ET cases.2 Identifying markers of greater imbalance might prompt clinicians to suggest precautions to lessen the likelihood of such occurrences.

In summary, ET patients with cranial tremors (neck, jaw, voice), those with older age of tremor onset, and those of current older age are more likely to manifest tandem gait difficulty and, possibly, be at increase risk for falls. Tandem gait difficulty was not correlated with severity of limb tremors. These data suggest that tandem gait difficulty and cranial tremors in ET may both be symptomatic of the same underlying pathophysiology, a disturbance of cerebellar regulation of the midline, which is distinct from its regulation of the limbs. Further studies, using additional clinical assessments as well as measures of postural sway and tandem gait on a treadmill could further define the observed associations.

Acknowledgments

R01 NS39422 and R01 NS42859 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Elan D. Louis: Research project conception, organization and execution; statistical analyses design and execution; manuscript writing (writing the first draft and making subsequent revisions).

Eileen Rios: Research project execution; manuscript writing (making subsequent revisions).

Ashwini Rao: Research project conception; manuscript writing (making subsequent revisions).

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Statistical Analyses: The statistical analyses were conducted by Elan D. Louis.

References

- 1.Singer C, Sanchez-Ramos J, Weiner WJ. Gait abnormality in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1994;9(2):193–196. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parisi SL, Heroux ME, Culham EG, Norman KE. Functional mobility and postural control in essential tremor. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(10):1357–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.07.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubble JP, Busenbark KL, Pahwa R, Lyons K, Koller WC. Clinical expression of essential tremor: effects of gender and age. Mov Disord. 1997;12(6):969–972. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolze H, Petersen G, Raethjen J, Wenzelburger R, Deuschl G. The gait disorder of advanced essential tremor. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 11):2278–2286. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.11.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronenbuerger M, Konczak J, Ziegler W, et al. Balance and motor speech impairment in essential tremor. Cerebellum. 2009;8(3):389–398. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bove M, Marinelli L, Avanzino L, Marchese R, Abbruzzese G. Posturographic analysis of balance control in patients with essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2006;21(2):192–198. doi: 10.1002/mds.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klebe S, Stolze H, Grensing K, Volkmann J, Wenzelburger R, Deuschl G. Influence of alcohol on gait in patients with essential tremor. Neurology. 2005;65(1):96–101. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167550.97413.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benito-Leon J, Louis ED. Clinical update: diagnosis and treatment of essential tremor. Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1152–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louis ED, Rios E, Applegate LM, Hernandez NC, Andrews HF. Jaw tremor: prevalence and clinical correlates in three essential tremor case samples. Mov Disord. 2006;21(11):1872–1878. doi: 10.1002/mds.21069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putzke JD, Uitti RJ, Obwegeser AA, Wszolek ZK, Wharen RE. Bilateral thalamic deep brain stimulation: midline tremor control. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(5):684–690. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.041434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obwegeser AA, Uitti RJ, Turk MF, Strongosky AJ, Wharen RE. Thalamic stimulation for the treatment of midline tremors in essential tremor patients. Neurology. 2000;54(12):2342–2344. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.12.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louis ED, Zheng W, Applegate L, Shi L, Factor-Litvak P. Blood harmane concentrations and dietary protein consumption in essential tremor. Neurology. 2005;65(3):391–396. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172352.88359.2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis ED, Ford B, Bismuth B. Reliability between two observers using a protocol for diagnosing essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1998;13(2):287–293. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis ED, Wendt KJ, Albert SM, Pullman SL, Yu Q, Andrews H. Validity of a performance-based test of function in essential tremor. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(7):841–846. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.7.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahn SER. Members of the UPDRS Development Committee. In: Fahn S, Marsend CD, Goldstein M, Calne DB, editors. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Health Care Information; 1987. pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis ED, Frucht SJ, Rios E. Intention tremor in essential tremor: Prevalence and association with disease duration. Mov Disord. 2009;24(4):626–627. doi: 10.1002/mds.22370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poston KL, Rios E, Louis ED. Action tremor of the legs in essential tremor: prevalence, clinical correlates, and comparison with age-matched controls. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(8):602–605. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benito-Leon J, Louis ED. Essential tremor: emerging views of a common disorder. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2(12):666–678. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umemura K, Ishizaki H, Matsuoka I, Hoshino T, Nozue M. Analysis of body sway in patients with cerebellar lesions. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1989;468:253–261. doi: 10.3109/00016488909139057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurice-Williams RS. Mechanism of production of gait unsteadiness by tumours in the posterior fossa. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38(2):143–148. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.38.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP, et al. Older onset essential tremor: More rapid progression and more degenerative pathology. Mov Disord. 2009;24(11):1606–1612. doi: 10.1002/mds.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alves G, Wentzel-Larsen T, Aarsland D, Larsen JP. Progression of motor impairment and disability in Parkinson disease: a population-based study. Neurology. 2005;65(9):1436–1441. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183359.50822.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kempster PA, Williams DR, Selikhova M, Holton J, Revesz T, Lees AJ. Patterns of levodopa response in Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 8):2123–2128. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klockgether T, Ludtke R, Kramer B, et al. The natural history of degenerative ataxia: a retrospective study in 466 patients. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 4):589–600. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norris F, Shepherd R, Denys E, et al. Onset, natural history and outcome in idiopathic adult motor neuron disease. J Neurol Sci. 1993;118(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90245-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]