Abstract

Background

New values and practices associated with medical professionalism have created an increased interest in the concept. In the United Kingdom, it is a current concern in medical education and in the development of doctor appraisal and revalidation.

Objective

To investigate how final year medical students experience and interpret new values of professionalism as they emerge in relation to confronting dying patients and as they potentially conflict with older values that emerge through hidden dimensions of the curriculum.

Methods

Qualitative study using interpretative discourse analysis of anonymized student reflective portfolios. One hundred twenty-three final year undergraduate medical students (64 male and 59 female) from the University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine supplied 116 portfolios from general practice and 118 from hospital settings about patients receiving palliative or end of life care.

Results

Professional values were prevalent in all the portfolios. Students emphasised patient-centered, holistic care, synonymous with a more contemporary idea of professionalism, in conjunction with values associated with the ‘old’ model of professionalism that had not be directly taught to them. Integrating ‘new’ professional values was at times problematic. Three main areas of potential conflict were identified: ethical considerations, doctor-patient interaction and subjective boundaries. Students explicitly and implicitly discussed several tensions and described strategies to resolve them.

Conclusions

The conflicts outlined arise from the mix of values associated with different models of professionalism. Analysis indicates that ‘new’ models are not simply replacing existing elements. Whilst this analysis is of accounts from students within one UK medical school, the experience of conflict between different notions of professionalism and the three broad domains in which this conflict arises are relevant in other areas of medicine and in different national contexts.

KEY WORDS: medical professionalism, medical education, qualitative research, students’ reflections

INTRODUCTION

Internationally, medical professionalism is changing1–6. Shifting priorities, including a focus on the importance of patient choice, issues of governance and the altering nature of expert knowledge, accompanying the rejection of old notions of unquestioned ‘autonomy’ and ‘privilege’, are transforming the doctor-patient relationship and stimulating debate about the concept of professionalism7. For instance, the National Health Service in the UK now urges doctors to be less paternalistic and to actively engage with patients’ preferences for treatment. In line with this debate, Tomorrow’s Doctors, the recently revised requirements of the regulatory body for UK medical schools, includes the introduction of ‘medical professionalism’ within undergraduate curricula8–11.

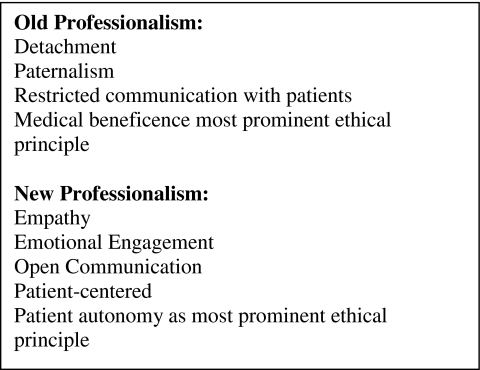

However, ‘medical professionalism’ remains an ambiguous term12–16. Definitions vary in their emphasis on values, attitudes, knowledge, skills and behaviours. An ‘old’ model, characterised by paternalism, emotional disengagement and establishing certainty, is being replaced by a ‘new’ one emphasising patient-centredness and collaboration (Box 1)17. Accordingly, whilst in the old variant detachment was viewed as a key feature of patient encounters17,18, empathy and shared decision-making now require doctors to consider their own emotions as a resource for providing more holistic forms of care19.

Box 1.

Examples of attributes associated with ‘old’ and ‘new’ professionalism

Reflective practice that incorporates critical learning is claimed to foster these new qualities20. Consequently, both written and verbal exercises designed to encourage this are becoming part of medical education, doctor appraisal and revalidation in the UK21–23. This study investigates how professionalism is understood and experienced via one such initiative for medical students training in Cambridge, England, and highlights the conflicts between ‘new’ and ‘old’ values. Encounters with dying patients and reflection on professional practice particularly illuminate such issues, since they are personally challenging, contest the notion of death as a medical failure24,25 and call the role of the doctor into question.

Despite recent reforms in the curriculum of UK medical students, it has been suggested that because relatively few physicians are formally trained in teaching or education, a more entrenched traditional ‘hidden curriculum’ is taught alongside the new elements26. The idea of a ‘hidden curriculum’ generally refers to those aspects of organisation and culture taken for granted that nevertheless exert a powerful influence on the norms and values imparted to students. For many years sociological studies have highlighted such cultural dimensions of medical education that influence the ways in which the next generation of doctors are socialised, including issues of hierarchy and working in teams27–29, detachment30,31, features of authority and dealing with uncertainty32,33. Indeed, it has been noted that for decades attempts to reform the medical curriculum have always been held back by the resistant nature of the overall ‘learning environment’, which is always far harder to change than the simple introduction of the formal curriculum34. We consequently take this argument as our starting point by looking at the ways features of the hidden curriculum lag behind and are experienced as conflicting with the new values underpinning education reform.

METHODS

Final year medical students in Cambridge meet patients approaching the end of life during general practice (GP) and hospital attachments. As required coursework they write portfolio items on two patients, one from each attachment. Key to this exercise is integrating issues arising from the interview with reflections of their own personal experiences. This study focuses on how different ideas are received and reproduced by a relatively young (typically early 20s) cohort of soon-to-be qualified doctors during the academic year 2007–2008. The University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics committee approved the study, and 86% of students (n = 123; 64 male, 59 female) gave informed consent for 234 reflective items: 116 from the GP and 118 from hospital settings. Each student was assigned a random identification number (ID), which is included with the quotes to demonstrate the breadth of the dataset presented.

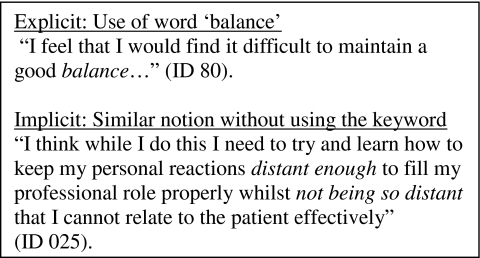

Analysis focused on the topic of ‘professionalism’, viewing the content of the portfolios as representative of general values imparted to students throughout their education. All items were coded and analysed in NVivo 8 using an interpretative approach. Following the social science traditions of two of the authors (EB and SC), the methodology employed a hermeneutic approach, striving to find meaning beyond straightforward discrete references35. Accordingly, rather than assuming the meaning of isolated sections of text in a reductive manner, they were always analysed in context and in relation to one another. Given the difficulty many students had in addressing the topic of end of life care, and consequently the very discursive descriptions of their observations, the authors were committed to code more than just those phrases in which a theme was referred to explicitly, and so included concerns that were expressed less directly. A coding scheme was derived from initial independent item analysis (EB, SC and SB) and adjusted through discussion. It was initially applicable to explicit statements by drawing on key words and then was augmented to include the more implicit references that potentially alluded more to the hidden dimensions of their teaching (see Box 2). The inclusion of these required careful interpretative readings of the entire text but provided an essential contribution to our overall analysis. The first author (EB) then led on-going analysis, with regular meetings to discuss emerging themes.

Box 2.

Examples of explicit and implicit references

RESULTS

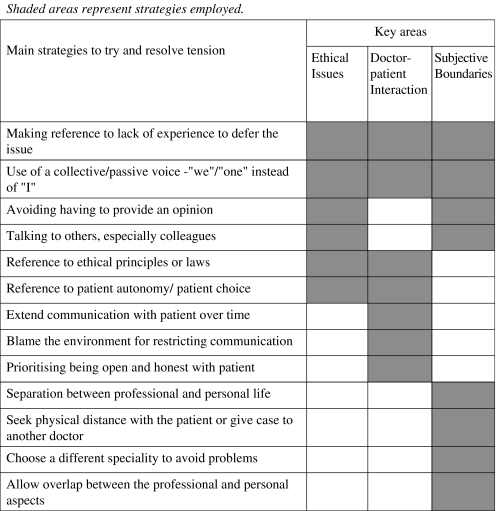

Reference to professional values was prevalent in all the portfolios; students emphasised the importance of choice and patient-centered care as well as values more associated with the ‘old’ model of professionalism, such as detachment and the importance of extensive technical knowledge. Reflections on practice-based experiences however frequently highlighted instances in which such values proved challenging. We consequently not only found that values of the old professionalism existed alongside new, but that students experienced their juxtaposition as problematic. Students made no distinction or applied any obvious hierarchy between what might be considered old and new values, or hidden versus formal teaching. Overall, we identified three main areas of potential conflict: ethical considerations, interactional issues and unease around establishing subjective boundaries. Tables 1 and 2 summarise the tensions experienced and the strategies used to address them.

Table 1.

Examples of Tensions

| Area of tension | Illustrative quotation | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical concerns | Pain-relief at end-of-life | “There remains a grey area between acceptable symptom control and actively hastening death” (ID 81) |

| Place of care/death | “Although many people wish to die at home, this cannot always be accommodated or is not felt to be consistent with best care, and this can create difficulties” (ID 58) | |

| Withholding/withdrawing treatment including DNAR and PEG tubes | “Once active treatment of an illness is not working, we have a responsibility not to cause our patients discomfort by unnecessary or fruitless intervention… [but the] diagnosis of dying is difficult, and that too often the default position for doctors is to say—‘Of course we go on’” (ID 97) | |

| Patient capacity—questioning patient autonomy | “Mrs. X is currently not lacking capacity; however… [there may be] a time when she may not be…. This raises the questions of whether she needs to consider issues like assigning the power of attorney over to her daughter….” (ID 87) | |

| Doctor-patient interaction | (Fear of) causing patient to be upset | “We must balance the benefits of discussion to the upset and anguish that may result” (ID 143) |

| Patient refuses information | “Evidently there are advantages to a position of open awareness… However, if Mr X does not wish to consider a poor prognosis, then it is disrespecting his wishes to impose information on him…” (ID 37) | |

| Confidentiality—breaking bad news in front of others and discussing care with family members | “… communicating a diagnosis in front of relatives could well be a breach of confidentiality; however, breaking news to a lone patient could be seen as lacking in compassion” (ID 26) | |

| Managing subjective boundaries | Attachment versus detachment | “…you do begin to imagine yourself and your family in the same situation as the patients or recall similar situations from your past…. However, it is also important not to become too emotionally attached to the patient. Keeping a balance between these two is very difficult” (ID 63) |

| Expressing emotion | “I also learned that one needs to be careful to express the right amount of emotion when such details are revealed by a patient. One should certainly show empathy, but at the same time the patient should certainly not be left feeling that they need to comfort you” (ID 67) | |

| Situations that bring up one’s personal experiences | “… whenever I deal with a patient receiving palliative care in the future I will take with me my own thoughts, emotions and experiences …[these] will influence my clinical practice in so many ways. Whether this will be for better or for worse I cannot say” (ID 57) |

Table 2.

Examples of Strategies

Ethics as a Source of Tension

“It made me realise how medical professionals have to face difficult decisions at times, balancing patients’ best medical interests, while respecting their wishes” (ID 110).

Although examining ethical and legal issues was an integral part of their assignment, the majority of students describe them as a key aspect of being a good modern doctor. However, they frequently highlighted conflicts between patient autonomy and medical beneficence (Table 1), reflecting their increased emphasis in health care policy36. For example, one wrote: “Patients receiving palliative care have very few choices they are able to make, so their autonomy in deciding where they would like to die is important” (ID 28).

In their accounts, autonomy is often thought to be jeopardised when patient capacity is in question; one student commented on the “difficult balance that must be reached when competency is fading” (ID 81). Many students resolved this by suggesting patients maintain a role in decision making through creating Advanced Directives; without these, in circumstances when treatment is withdrawn, “the decision is a little more difficult and we [doctors] have to balance…beneficence and non-maleficence” (ID 45). Here, older ideas of authority and expertise came to the fore.

Table 2 lists strategies used to address these ethical tensions. Some students drew on policy or legal principles as a key resource to provide a solution. For example, with reference to the taught notion of ‘the doctrine of double effect’, one described how “if you are giving analgesia in order to relieve pain [which] might have the foreseeable result of shortening life, but without intention, then you are acting in the best interests of the patient and this is not illegal” (ID 94). Others tried to establish a position of authority or certainty using what can be termed a collective voice. By altering pronouns and stating “we…” rather than using the first person, they adopted a de-personalised stance that also subtly distributes responsibility across the profession as a whole. This tactic was indicative of a more general value alluded to that is no longer a feature of their formal training: that as doctors a detached, clear and rational approach both benefits the patient most and best befits the profession as a whole.

Nevertheless, many students felt tensions remained unresolved and the application of abstract, external criteria insufficient. Some referred to their general lack of experience or status as a student, stating that although at the moment they felt ill-equipped, in time they could “work on” (ID 63) the problems. The aspiration that in the future they would have greater skills and resources to resolve what currently was encountered as problematic was nevertheless doubted by others who described how core contradictions were intrinsic to contemporary medical practice and required them to individually discover their “own ethical absolutes” (ID 37).

Interacting with Patients

“It is a delicate balancing act: you do not want to shy away from difficult areas, but then equally you must not cause psychological harm by forcing the issue when the patient is not ready to do so” (ID 145).

Interacting with patients proved to be a further area of tension between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ values communicated to the students within their entire learning environment. Whilst Cambridge medical students receive extensive communication skills training37, they nonetheless worry about the possible harm information can cause (Table 1). Their main concern was trying to be frank but not upsetting patients. It was also evident that students struggled with their own emotional reactions. Although some explicitly described how the doctor should ideally strike “an intuitive balance between being sensitive on the one hand and being open and honest on the other” (ID 120), students invariably struggled with this in their own attempts to find equilibrium between knowing what and how much to say, and when and where discussions should take place.

Issues of confidentiality and informed consent around instances of breaking bad news or discussing a patient’s care with others further complicated students’ evaluations. In an attempt to resolve such difficult experiences, one student wrote that “By gaining patient consent to postponing a discussion until family arrive, one can both respect autonomy of the patient and allow the close family to feel engaged” (ID 26). Some employed strategies that referred to external principles to establish how much, and what kind, of information should be provided (Table 2). However, the immediacy of actual encounters frequently forced them to make decisions instantly. As a consequence, a proportion discussed giving patients with what they called “warning shots” (ID 112), a technique learnt in class to indicate that bad news is about to come. Yet, the strategy also serves the students deferring the issue, and having to know what the appropriate amount to say might be.

Finally, many reported that medical environments, such as the hospital wards, were rarely conducive to distressing conversations. Although described ostensibly in terms of patient experience, this quite clearly was also relevant for how they dealt with things themselves. Concern was raised over the physical space not being sufficiently private or appropriate—“pulling the curtain…did little to provide a sense of confidentiality or privacy” (ID 98). Others concentrated less on the physical and more on the general work environment, predicting that in the future they simply “will not have the time I want for each patient” (ID 61) since already consultations provide “hardly even enough time for a full examination, let alone a decent talk” (ID 132). Attributing the physical environment and pressures of workload to generating tensions placed blame on unavoidable external factors that were therefore not their responsibility to resolve.

Managing Subjective Boundaries

“In medicine we face a difficult balance. We have a professional duty to the patient and their family. However, we are also individuals and carry with us our own experiences… We cannot be automatons, suppressing our experiences, nor is it good for clinical practice. Combining professional and personal aspects brings humanity… where it matters most” (ID 129).

In line with the new values promoted in their lectures, students acknowledge that their personal experiences both influence and can provide a valuable resource for their professional practice. One described how meeting the patient “made me realise that it may not be possible to keep personal and professional feelings separate” (ID 87). Unlike past generations that upheld a more distinct divide between their professional and personal selves38, and a clear distinction between knowledge and emotion, new doctors are now encouraged to show empathy and engage with their feelings. The ability to maintain an unambiguous subjective boundary consequently becomes blurred (Table 1), generating a further source of uncertainty.

The student portfolios, however, reveal how they receive mixed messages, even within the formal curriculum, to be sensitive and that it is “ok to sometimes be emotional with patients and their families” (ID 70), but never to breakdown in front of them. They internalised and reiterated these mixed values, stating such things as, “one should certainly show empathy, but at the same time the patient should not be left feeling that they need to comfort you” (ID 67). The resulting tension is further exacerbated by the hidden curriculum, in which some clinicians continue to exemplify what students report as “the need for self-preservation” (ID 68) and provide an objective approach even when dealing with very emotional situations. By overtly stating that they try to find a balance between providing care yet ensuring they protect themselves, many students mix ‘old’ and ‘new’ ways of relating to patients and guarding boundaries. One reported having developed “the art of being empathetic” without being “emotionally affected” (ID 45), while others described how they adopt a modern professional persona by nevertheless physically distancing themselves from patients.

Strategies for Handling Tensions

“I learnt that there is far more too [sic] a good doctor than medical knowledge and I should never be afraid of feeling sad for someone in this [end of life] situation” (ID 30).

As described, students employed a variety of strategies for handling the various tensions they encountered (Table 2). Whilst some drew on explicitly taught elements, such as ethical principles or specific communication skills, these were rarely sufficient in themselves. Moreover, although some referred to their status as a student or lack of experience to explain the difficulties encountered, this tactic was rarely regarded as straightforward, as the following statement captures:

“As a medical student it is very easy to hide behind the ‘I’m sorry, I’m only a student, why don’t you ask the doctor when they come round’ excuse… However, if I imagine myself as a patient asking a doctor a direct question I am almost certain that I would want a straight answer” (ID 99).

Although several of the strategies observed are derived from taught skills, reflecting how negotiating dilemmas is now an expected aspect of being a modern-day doctor, other significant tensions are derived from the mixed messages they receive and the inability of didactic training to provide straightforward solutions. Whilst students took comfort from the fact that this exercise was merely part of their education, some recognised that a simple accumulation of knowledge was never going to provide entire solutions. They describe how a range of other attitudes, including engaging with their own emotional reactions and sensibilities, would be at the centre of successfully dealing with such issues in the future. To that end, some explicitly stated that they wanted more experience, or simply have sufficient time to “step back and have a clearer view of the situation one is in, and to reassess the situation” (ID 131). This general insight is worth noting; the potential conflict experiences between old and new, and hidden and formal curricula, might only ever be resolved through on-going experience. This further suggests that many of the new values might not be easily ‘taught’ in a traditional way and can only ever be promoted through practice itself.

DISCUSSION

All of the students encountered challenges that required them to try and balance values characteristics of ‘old’ and ‘new’ forms of medical professionalism. Ethics, interaction and managing subjective boundaries all generated areas of conflict that they wrestled with in their assignments. Students addressed these tensions in a variety of ways, with strategies drawn from both formally taught skills and personal resources.

This study benefits from its large dataset and the inclusion of more implicit references in our analysis alongside explicit mention of issues identified as key themes. In combination, this provides a rich and detailed account of the students’ overall experience of professional values when confronting people at the end of life. The high response rate suggests the potential for non-participation bias was small. In practice, the majority of those who did not give their consent are likely to be students who were absent during the recruitment session, although this cannot be ascertained because of issues of anonymity. A potential criticism is that the data were taken from required coursework and students might have just written what was expected of them. Acknowledging this, we view the items submitted as illustrative of the extent to which the values of a ‘new’ professionalism have been absorbed and then actively reiterated in their submissions.

Despite being limited to one medical school, the study describes students confronted with many of the ethical and personal dilemmas of modern medicine. Students in other medical schools appear to identify similar issues20,25,39–41. However, unlike other studies that focus on the severity or frequency of dilemmas10 or view the conflicts as an effect of students struggling not to lose personal engagement42, we focused on the nature of the tensions, linking the challenges students face with the inherent conflicts in the nature of medical professionalism today43.

In parallel with shifts from ‘old’ to ‘new’ values of professionalism, conflicts between the formal and the hidden curricula may also generate tensions44. In our study, the formal curricula is explicitly designed to embrace the ‘new’, leaving the ‘old’ to be communicated through more informal and hidden aspects of teaching. Yet for the students trying to personally reflect on their experiences and summatively draw from their entire educational experience for the exercise, no distinction is made between these two domains. Large organisations like the University of Cambridge Clinical School and the National Health Service have institutional memories45—collective experiences and concepts. These are communicated imperceptively through teaching elements as well as the very structures and policies that shape the educational environment. This feature serves to complicate understandings of medical education; it emphasises the extent to which values are embedded in the routines and practices of the organisation, and cannot therefore be simply addressed through redesigning curricula or individuals championing change.

Our study suggests that tensions arise primarily because of different values that underlie the concept of professionalism throughout their education, rather than anything that is specific to end of life care. Whilst topics central to the everyday practice of medicine are particularly evident in palliative care46, they are made highly visible by students who see themselves on the cusp of becoming members of the profession themselves. Whilst it is likely that the concept of professionalism always has contained a wide variety of underlying values and principles that are not always commensurate with each other, we have argued that a more widespread shift in values over recent years has generated greater variance and hence more contradictory positions around what it means to be a good doctor. Our findings add to the literature on medical professionalism, which is rich in doctors’ anecdotal experiences47,48, highlights the stresses and conflicts doctors face44,49,50 and illustrates a current amalgamation of definitions with conflicting values51. Specific national and local contexts are likely to generate differently nuanced versions of these issues, which might only be identified through comparative work.

CONCLUSION

The integration of ‘new’ professional values taught in medical school is at times problematic for students in any health care system that maintains elements, whether overtly or not, of the ‘old’ paradigm. The areas of potential conflicts outlined—ethics, patient interaction and managing subjective boundaries—are not limited to medical school or end of life care. Our analysis suggests that ‘old’ variants of professionalism are not simply being replaced by ‘new’ ones delivered by a redesigned curriculum, but rather that values from each can emerge in a range of medical contexts. As a result, professionalism does not consist of a set of fixed or abstract concepts, but rather surfaces through medical practice.

If individual reflection is now heralded as an essential component of the ‘new’ professionalism, as indicated by the compulsory student exercise we have drawn on here, it should be acknowledged that it demands a dynamic engagement with the wide range of often contradictory and shifting ideas and beliefs from both formal and more hidden aspects of their education. This study illustrates that overt commitment to more empathic and patient-centered approaches to medical care do not necessarily replace other more prescribed values and behaviours that remain part of a hidden curriculum embedded in institutional practices. Integration of ‘new’ core values and skills into good medical practice is not a smooth or simple transition. Additionally, it seems any simple attempt to communicate them through formal teaching is unlikely to prepare students for the reality of medical encounters. Instead, the experience of tension and the individual desire to seek balance and resolution across a wide range of issues may themselves be key and lasting features of medical professionalism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the students who gave their consent for their portfolios to be in this study. We are grateful to the students and other colleagues who have provided feedback on previous drafts, including Diana F. Wood, John Benson, Thelma Quince and James Brimicombe. We further thank the James Knott Family Trust for funding this research, with additional funding from the General Practice and Primary Care Research Unit at the University of Cambridge.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Ethical Approval The study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics committee. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Footnotes

Contributors

SB, SC, Diana F. Wood (Clinical Dean), John Benson, Thelma Quince and James Brimicombe were involved in the initial planning and ethics application. SB obtained consent from students. James Brimicombe managed and anonymized the data. SC and SB further developed the research with EB, who then led the analysis and reporting with support from SC and SB. DFW reviewed early versions of the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to and approve of the final version. SB is the guarantor.

Funding

This study was funded by the James Knott Family Trust. The funders had no part in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the report, and the decision to submit the article for publication. SB is a Trustee of the James Knott Family Trust: his work as a researcher in the University of Cambridge is independent from the funders. SB is funded by Macmillan Cancer Support as a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, and is a member of the NIHR CLAHRC for Cambridge and Peterborough (Collaborations for Applied Health Research and Care). Additional funding was received from the General Practice and Primary Care Research Unit at the University of Cambridge.

References

- 1.Mook WNKA, Grave WS, Wass V, O'Sullivan H, Zwaveling JH, Schuwirth LW, et al. Professionalism: evolution of the concept. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:e81–e84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Southon G, Braithwaite J. The end of professionalism? Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:23–28. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levenson R, Dewar S, Shepherd S. Understanding Doctors: Harnessing Professionalism. London: King's Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medical Professionalism Project Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physicians' charter. Lancet. 2002;359:520–522. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doctors in Society: Medical Professionalism in a Changing World. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Project Professionalism. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Board of Internal Medicine; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith R. Medical professionalism: out with the old and in with the new. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:48–50. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.2.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's Doctors: Outcomes and Standards for Undergraduate Medical Education. GMC; 2009.

- 9.Stern DT, Papadakis M. The developing physician—becoming a professional. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1794–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mook WNKA, Grave WS, Luijk SJ, O'Sullivan H, Wass V, Schuwirth LW, et al. Training and learning professionalism in the medical school curriculum: current considerations. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:e96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldie J. Integrating professionalism teaching into undergraduate medical education in the UK setting. Med Teach. 2008;30:513–527. doi: 10.1080/01421590801995225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen R, Dewar S. On Being a Doctor: Redefining Medical Professionalism for Better Patient Care. London: King's Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mook WNKA, Luijk SJ, O'Sullivan H, Wass V, Zwaveling JH, Schuwirth LW, et al. The concepts of professionalism and professional behaviour: conflicts in both definition and learning outcomes. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:e85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erde EL. Professionalism's facets: ambiguity, ambivalence, and nostalgia. J Med Philos. 2008;33:6–26. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones L, Green J. Shifting discourses of professionalism: a case study of general practitioners in the United Kingdom. Sociol Health Illn. 2006;28:927–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Hatala R, McNaughton N, Frohna A, Hodges B, et al. Context, conflict, and resolution: a new conceptual framework for evaluating professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75:S6–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lief HI, Fox RC. Training for “detached concern” in medical students. In: Lief HI, Lief VF, Lief NR, editors. The Psychological Basis of Medical Practice. New York: Harper and Row; 1963. pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLeod RD. On reflection: doctors learning to care for people who are dying. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1719–1727. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halpern J. From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medical Practice. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feest K, Forbes K. Today's Students, Tomorrow's Doctors: Reflections from the Wards. Oxon: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004;79:351–356. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane U. Revalidation: Project Initiation Document. 2009. Available at: www.gmc-uk.org/Project_Initiation_document.pdf_25397052 Accessed July 8, 2010.

- 23.Irvine D. The relationship between teaching professionalism and licensing and accrediting bodies. In: Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y, editors. Teaching Medical Professionalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams CM, Wilson CC, Olsen CH. Dying, death, and medical education: student voices. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:372–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Rosenbaum ME, Lobas J, Ferguson K. Using reflection activities to enhance teaching about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1186–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. Br Med J. 2004;329(7469):770–773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merton R, Reader G, Kendall P. The Student-Physician: Introductory Studeies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker HS, Geer B, Hughes HC, Strauss AL. Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinclair S. Making Doctors. Oxford: Berg; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helman C. The dissection room. In: Body Myths. London: Chatto and Windus; 1991:114-23

- 31.Good BJ. Medicine, Rationality, and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloom S. The medical school as a social organisation: the source of resistance to change. Med Educ. 1989;23:228–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1989.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brosnan C. Pierre Bourdieu and the theory of medical education: thinking ‘relationally’ about medical students and medical curricula. In: Brosnan C, Turner B, editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Medical Education. Oxon: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403–407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lock M, Gordon D, editors. Biomedicine Examined. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacKenzie CR. What would a good doctor do? Reflections on the ethics of medicine. HSS J. 2009;5:196–199. doi: 10.1007/s11420-009-9126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, Draper J. Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Acad Med. 2003;78:802–809. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Block SD, Billings JA. Becoming a Physician: Learning from the Dying. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:1313–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Rabow MW, Wrubel J, Remen RN. Promise of professionalism: personal mission statements among a national cohort of medical students. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):336–342. doi: 10.1370/afm.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer MA, Harrell HE, Haley H, Cifu AS, Alper E, Johnson KM, et al. Between two worlds: a multi-institutional qualitative analysis of students’ reflections on joining the medical profession. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:958–963. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0508-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howe A, Barrett A, Leinster S. How medical students demonstrate their professionalism when reflecting on experience. Med Educ. 2009;43:942–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Branch WT. Small-group teaching emphasizing reflection can positively influence medical students' values. Acad Med. 2001;76:1171–1172. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wear D. "Face-to-face with it": medical students' narratives about their end-of-life education. Acad Med 2002;77:271–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Hafferty FW. Into the Valley: Death and the Socialization of Medical Students. New Haven: Yale University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linde C. Working the Past—Narrative and Institutional Memory. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doyle D. Foreword. In: Randall F, Downie RS, editors. Palliative Care Ethics: A Good Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. vii–ix. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lelonek M, Zink T. First code. Minn Med. 2007;90(8):31–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brainard AH, Brislen HC. Learning professionalism: a view from the trenches. Acad Med. 2007;82:1010–1014. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285343.95826.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2005;80:1613. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Caplan RP. Stress, anxiety, and depression in hospital consultants, general practitioners, and senior health service managers. Br Med J. 1994;309:1261–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Van De Camp K, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Grol RPTM, Bottema BJAM. How to conceptualize professionalism: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2004;26:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed]