Abstract

Necrosis is associated with an increase in plasma membrane permeability, cell swelling, and loss of membrane integrity with subsequent release of cytoplasmic constituents. Severe redox imbalance by overproduction of reactive oxygen species is one of the main causes of necrosis. Here we demonstrate that H2O2 induces a sustained activity of TRPM4, a Ca2+-activated, Ca2+-impermeant nonselective cation channel resulting in an increased vulnerability to cell death. In HEK 293 cells overexpressing TRPM4, H2O2 was found to eliminate in a dose-dependent manner TRPM4 desensitization. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments revealed that the Cys1093 residue is crucial for the H2O2-mediated loss of desensitization. In HeLa cells, which endogenously express TRPM4, H2O2 elicited necrosis as well as apoptosis. H2O2-mediated necrosis but not apoptosis was abolished by replacement of external Na+ ions with sucrose or the non-permeant cation N-methyl-d-glucamine and by knocking down TRPM4 with a shRNA directed against TRPM4. Conversely, transient overexpression of TRPM4 in HeLa cells in which TRPM4 was previously silenced re-established vulnerability to H2O2-induced necrotic cell death. In addition, HeLa cells exposed to H2O2 displayed an irreversible loss of membrane potential, which was prevented by TRPM4 knockdown.

Keywords: Calcium, Mutant, Necrosis (Necrotic Death), Oxidative Stress, TRP Channels, Hydrogen Peroxide, TRPM4

Introduction

The transient receptor potential (TRP)5 ion channel superfamily comprises a broad variety of cation-selective channels key to many physiological processes, including sensation, cell proliferation, and cell death (1, 2). TRPM4 is a Ca2+-activated and voltage-dependent monovalent cation selective channel corresponding to the melastatin subfamily of TRP channels (3). A distinct feature of TRPM4, as well as TRPM5 channels is that upon activation by intracellular Ca2+, currents exhibit a fast decay due to a decrease in the sensitivity to Ca2+ (3–6). In addition, these channels have been shown to depend on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) (7, 8), suggesting that the current decay or desensitization of TRPM4 can be explained partially by a loss of PI(4,5)P2 from the channels.

TRPM4 features similar biophysical and pharmacological properties to Ca2+-activated, Ca2+-impermeable nonselective cation channels (CAN) described in many excitable and nonexcitable cells (9, 10). CAN channels are widely expressed among different tissues exhibiting several common characteristics, such as a low open probability when studied in situ, a conductance of 15–30 pS under symmetrical Na+ conditions, and a weak voltage-dependent gating. In addition, these channels are activated by intracellular Ca2+ and blocked by ATP, suggesting that their activation may be coupled to the metabolic status of the cell. Furthermore, some CAN channels have been found to be activated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) in a number of cell types (11–17). Because of their ion selectivity, an unregulated activation of CAN channels may have detrimental consequences for cell homeostasis, expressed by a collapse of the Na+ and K+ transmembrane gradients, a reduction of the membrane potential, and an increased turnover rate of the Na+/K+-ATPase pump and thus, increased ATP consumption. Several of these conditions observed under oxidative stress may lead to necrotic cell death. Thus, distinctive and necessary events are membrane depolarization and cell swelling, a phenomenon known as necrotic volume increase (18, 19). Indeed, pharmacological inhibition of these channels prevents cytosolic Na+ and Ca2+ overload, cell volume increase, and death of liver and neuronal cells exposed to oxidative damage (15, 20). More recently, Gerzanich et al. (21) demonstrated that in vitro expression of TRPM4, a molecular candidate for CAN channels as previously suggested (10, 22), predisposes to cell death upon ATP depletion.

In this work we addressed the question whether TRPM4 is modulated by ROS. Here we show that the Cys1093 residue participates in mediating the effect of H2O2 on TRPM4 current desensitization. As a result, the transmembrane potential collapses eventually leading to severe metabolic derangement and subsequent cell death.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Cells

T-REx-293 cells, a HEK 293-derived cell line, were obtained from Invitrogen and cultured in DMEM/F-12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2 mm glutamine. HeLa cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in DMEM, low glucose supplemented with 5% FBS and 2 mm glutamine. Both cell lines were maintained in a 95% air, 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C, passaged twice a week and used from passages 5–10.

Tetracycline-inducible T-REx-293 hTRPM4 Cells

The full-length human TRPM4b cDNA containing a FLAG epitope tag in the N terminus was cloned into a modified version of the pcDNA4/TO vector (Invitrogen) and transfected into T-REx-293 cells that stably express plasmid pcDNA6/TR for Tet-repressor expression (Invitrogen). Cells were placed under zeocin selection and zeocin-resistant clones were screened for tetracycline-inducible expression of the FLAG-tagged TRPM4 protein. The medium was supplemented with blasticidin (5 μg/ml, Invitrogen) and zeocin (0.4 mg/ml, Invitrogen). For most experiments, cells were resuspended in medium containing 1 μg/ml of tetracycline (Invitrogen) 18–24 h before experiments. For electrophysiological experiments cells were plated on coverslips and 1 μg/ml of tetracycline was added for 16–24 h before performing experiments.

shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa Cell Clones

A short-hairpin RNA for TRPM4 was constructed according to Ref. 23. Briefly, 64-mer primers were designed to include a 19-mer TRPM4 sequence (24), its complement, a spacer region, 5′ BglII site and 3′ HindIII sites. A scrambled duplex was used as a control. The annealed double-stranded DNA was cloned into the pSUPER.retro.neo vector (Oligoengine, Seattle, WA) and HeLa cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and placed under G418 (Sigma) selection. G418-resistant clones were screened for TRPM4 mRNA reduction and clones were kept in a medium supplemented with G418 (0.5 mg/ml; Invitrogen).

Quantitative PCR

RT and qPCR were performed to measure TRPM2, TRPM4, TRPM7, and the housekeeping gene GADPH mRNA levels in HeLa cells using the primers described in Ref. 25. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). DNase I-treated RNA was used for reverse transcription using the SuperScript II kit (Invitrogen). Equal amounts of RNA were used as templates in each reaction. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (AB Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Data are presented as relative mRNA levels of the gene of interest normalized to relative levels of GADPH mRNA. These values were calculated from a standard curve generated with HeLa wild type cDNA.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Mutagenesis (C1093A) of the recombinant human TRPM4 cDNA in the pcDNA4/TO vector was performed using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions, using the primers: forward, 5′-TGCTCAGGCAATTGGCTAGGCGACC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGTCGCCTAGCCAATTGCCTGAGCA-3′. The nucleotide sequence of the mutant was verified by DNA sequencing.

Electrophysiology

Whole cell patch clamp experiments on T-REx-293 hTRPM4 cells were performed 16–24 h after tetracycline induction. In acute overexpression experiments, HEK 293 cells were transfected with the plasmid containing the C1093A mutation using Lipofectamine 2000 and electrophysiological experiments were conducted 48 h post transfection. For whole cell experiments, the internal pipette solution contained (in mm) CsCl 140, NaCl 5, MgCl2 1, BAPTA 1, CaCl2 0.83, and pH 7.2 adjusted with CsOH. The bath solution (in mm) was: NaCl 140, CsCl 5, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1, glucose 10, HEPES 10, tamoxifen 0.01, and pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH. For current clamp experiments, the pipette solution contained (in mm): KCl 140, NaCl 5, HEPES 10, CaCl2 0.01, MgCl2 1, pH 7.2, adjusted with KOH and the bath solution contained (in mm), NaCl 140, KCl 5, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1, glucose 10, HEPES, 10, tamoxifen, 0.01, and pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. In inside-out experiments, the pipette solution contained (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, adjusted with KOH. The bath solution contained (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.01 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 1 HEDTA, pH 7.2, adjusted with NaOH. Free [Ca2+] of the solutions was calculated using the program WinMaxc, version 2.50 with the appropriate Ca2+ buffers. Patch clamp experiments were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Data were digitized at 10 kHz and low-pass filtered at 1 kHz. The pClamp 9.2 software (Molecular Devices Corp.) was used for data acquisition and analysis. Patch electrodes (∼3 MΩ resistance) were pulled from borosilicate glass (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) using a BB-CH puller (Mecanex SA, Geneva, Switzerland). When applicable, voltages were corrected for liquid junction potentials. All experiments were conducted at 22 ± 2 °C.

Cell Death Determination by LDH Release

T-REx-293 hTRPM4 cells were exposed to experimental conditions in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin instead of FBS. Cells were exposed to H2O2 (Merck KgaA-Chemicals, Darmstad, Germany) for 4 h and viability was determined 20 h later. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in cell supernatants was determined by a colorimetric end point kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). A calibration curve was produced to ensure linearity in the range studied. Background was subtracted and data were expressed as the fraction of maximum release measured in the presence of 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma).

Cell Death Determination by FACS

T-REx-293 hTRPM4 or HeLa cells were exposed to experimental conditions in DMEM/F-12 or DMEM-low glucose, respectively, supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin instead of FBS. Cells were exposed to H2O2 for 4 h and viability was determined 20 h later. In selected experiments, DMEM was made following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) and reagents to facilitate Na+ replacement. HEPES (25 mm) was used as a buffer instead of NaHCO3 and cells were kept at 37 °C without CO2. Sodium was replaced equimolarly by N-methyl-d-glucamine or sucrose. Osmolarity was kept constant across different solutions. Osmolarity was measured with a micro-osmometer (Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min and the pellet was suspended in 200 μl of PBS. Afterward, cells were washed once with PBS and stained with propidium iodide (PI, 10 μg/ml, Sigma) for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. DNA content was analyzed with a flow cytometry system (FACSCanto, BD Biosciences). A minimum of 10,000 cells/sample were analyzed. PI intensity analysis was performed using FACSDiva software version 4.1.1 (BD Biosciences). Cell death was determined according to a previously described method (26). In brief, PI enters the cell upon plasma membrane disruption thus binding to DNA. Because its fluorescence is proportional to the DNA content, live cells (M0) present a low fluorescence, whereas in necrotic cells (M2) PI binds mainly to intact DNA showing a high fluorescence. Apoptotic cells with degraded DNA (M1) bind less PI than necrotic cells but its fluorescence is higher than M0.

Cell Volume Measurements

shRNA-TRPM4 and shRNA-SS HeLa cells cultured on 25-mm glass coverslips were put into a recording chamber mounted on a confocal spinning disk system (DSU Olympus, Germany) and changes in cell water volume of individual cells were assessed by measuring variations in the concentration of the intracellularly trapped fluorescent dye red calcein (Invitrogen), with an excitation wavelength of 555 nm and emission wavelength between 580 and 620 nm recorded with a band pass filter, similar as previously described (27, 28). Briefly, cells were loaded with 5 μm calcein-AM for 5 min and then superfused with an isosmotic solution for 15 min before adding H2O2. Images were obtained at 10-s intervals and the fluorescence of a ∼10-μm2 area in the center of a cell was measured. Data are presented as Vt/V0 values, where V0 is the cell water volume in isosmotic solution at time 0 and Vt is the cell water volume at time t. Vt/V0 was calculated from the fluorescence intensity ratio F0/Ft.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were harvested and collected by centrifugation (3,000 × g at 4 °C) and lysed in a lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 5 mm NaF, 1 mm PMSF, 1.5 μg/ml of aprotinin, 10 μg/ml of antipain, 10 μg/ml of leupeptin, 0.1 mg/ml of benzamidine, pH 7.4). Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and proteins from the supernatants were size-fractionated in 6 and 12% SDS-PAGE (29) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG and anti-β-actin polyclonal antibodies (Sigma), respectively.

Reagents

Unless stated, all chemicals and reagents were from Merck KgaA-Chemicals (Darmstad, Germany) and Sigma.

Data Analysis

All results are presented as mean ± S.E. from 3 or more independent experiments. Statistical analysis of the data were performed using Statgraphics Plus 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni or Dunns post hoc tests and Student's t test were used and considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Hydrogen Peroxide Removes TRPM4 Desensitization in a Heterologous Overexpression Model

To address the role of TRPM4 in ROS-mediated cell death, we first explored whether TRPM4 would be sensitive to ROS. Fig. 1A shows an averaged time course of currents measured at 100 mV activated by 600 nm Ca2+ in the pipette solution in T-REx-293 hTRPM4 cells overexpressing TRPM4 under the control of a tet inducible system (HEK-TRPM4 tet+) (24) (supplemental Fig. S1A). As expected for heterologously overexpressed TRPM4 channels, the current was transient and appeared to be completely abolished after 2 min and showed no reactivation even at 20 min (supplemental Fig. S1B) (7, 30). To discard that the recorded current was carried by Cl− ions, experiments were performed in which the extracellular NaCl concentration was reduced to 40 mm. As predictable for a cation current, the reversal potential shifted to −31 mV, close to the expected value of −29 mV (n = 8). There was no influence of H2O2 on the reversal potential of the currents. Fig. 1B depicts representative control whole cell current traces at −100 and 100 mV recorded at 30 (peak) and 120 s after breaking into the cell. The I-V curves obtained from representative voltage ramps, measured at the peak and 120 s, display the typical rectification found for TRPM4 currents (Fig. 1C) (4). To study the effect of H2O2 on TRPM4 currents, HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells were exposed to 200 μm H2O2 throughout the recording. In the experiments with H2O2, tamoxifen was used to avoid contamination with volume-activated Cl− currents (31). As depicted in Fig. 1D, the current (measured at 100 mV) remained activated and showed very little desensitization. The loss of desensitization was also evident when observing traces recorded at −100 and 100 mV (Fig. 1E). The I-V relationship was comparable with control conditions at the peak and at later times during the experiment, yet showed less inward rectification (Fig. 1F). The effect of H2O2 was dose-dependent and became apparent at concentrations ≥50 μm without significant modification of the voltage dependence (supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). The effect of H2O2 on TRPM4 currents was also observed in whole cell (supplemental Fig. S1E) and inside-out recordings (supplemental Fig. S1F) upon exposure to H2O2 after current desensitization. Flufenamic acid (100 μm) or glibenclamide (10 μm), two known inhibitors of TRPM4 (32) significantly reduced this non-desensitizing current from 148 ± 15.8 to 5 ± 2.1 and 9.6 ± 5.6 pA/pF, respectively (not shown).

FIGURE 1.

H2O2 removes desensitization of TRPM4 currents. A, time course of averaged (mean ± S.E., n = 10) TRPM4 currents recorded at 100 mV evoked by 600 nm Ca2+ in the pipette solution from tetracycline-induced (1 μg/ml) (HEK-TRPM4 tet+) cells. The voltage protocol consisted in a 400-ms step to −100 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV followed by a 400-ms step to 100 mV applied at 0.4 Hz (only positive currents are shown). The depicted current corresponds to the mean current recorded during the 20-ms final pulse. B, representative whole cell current traces at −100 and 100 mV obtained with the same protocol as described above. C, representative I-V relationship of TRPM4 currents using a voltage ramp from −100 to 120 mV. The ramp protocol consisted of an 800-ms ramp from −100 to 120 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV. D, time course of averaged (mean ± S.E., n = 8) TRPM4 currents from HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells exposed to 200 μm H2O2 recorded at 100 mV with 600 nm Ca2+ in the pipette solution. E, representative whole cell current traces from HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells exposed to 200 μm H2O2 and dialyzed with 600 nm Ca2+. F, representative I-V relationship as in B from HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells challenged with 200 μm H2O2. In all panels, a indicates the peak currents (30 s after establishing the whole-cell configuration) and b denotes the current after 120 s of cell dialysis.

The Cys1093 Residue Participates in Mediating the Effect of H2O2

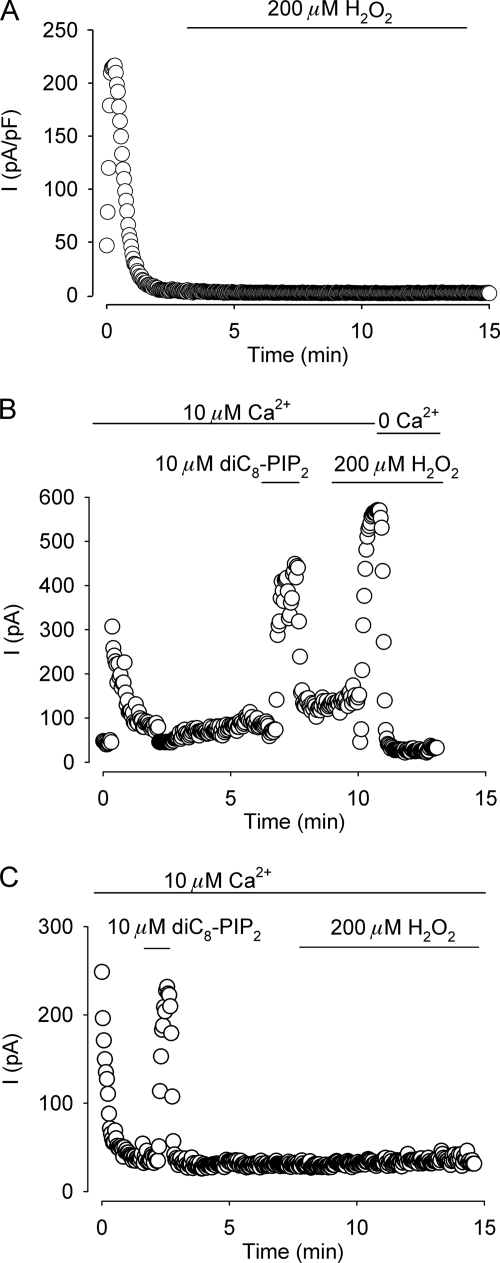

Because of the striking similarity between the effect of H2O2 and an increased calmodulin binding at the C terminus region on whole cell current desensitization (30), we focused our interest in the cysteine residue located at position 1093 in the C terminus next to the beginning of the third CaM binding motif spanning the Arg1095-Thr1151 sequence (30). It should be noted that no cysteine residues were found close to the other predicted CaM binding motif located at the C terminus of the protein. To that end, this cysteine residue was mutated to alanine and the effect of H2O2 on HEK 293 cells overexpressing the mutation was explored electrophysiologically. Fig. 2A shows a representative time course experiment of whole cell currents measured at 100 mV activated by 600 nm Ca2+ in the pipette solution. In contrast to wild type TRPM4 currents (Fig. 1D), exposure to 200 μm H2O2 had no effect on current desensitization, suggesting that for H2O2 to be effective requires the Cys1093 residue. Because of the complexity of the processes and the variety of factors that apparently govern the desensitization of TRPM4 currents, we next asked the question whether the rescue from desensitization by PI(4,5)P2 of this mutant was hindered. Fig. 2 depicts representative time course experiments of inside-out patches from HEK 293 cells overexpressing wild type TRPM4 channels (B) or channels carrying the C1093A mutation (C). The current was activated in the presence of 10 μm Ca2+ in the bath solution and recorded at 100 mV. As shown, the C1093A mutant retains the sensitivity to PI(4,5)P2, indicating that H2O2 does not hamper the action of PI(4,5)P2.

FIGURE 2.

C1093A mutant channels do not respond to H2O2. A, representative time course of TRPM4 whole cell currents from HEK 293 cells overexpressing the C1093A mutant exposed to 200 μm H2O2 (indicated by the bar) recorded at 100 mV with 600 nm Ca2+ in the pipette solution (n = 12). B and C, representative time course of inside-out recordings from membrane patches from HEK 293 cells overexpressing wild type TRPM4 channels (B) or C1093A mutants (C) recorded at 100 mV and activated by 10 μm Ca2+ in the bath solution. Bars indicate exposure to the water-soluble form of PI(4,5)P2 (dioctanoyl-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (diC8-PIP2), Echelon Biosciences Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) or 200 μm H2O2 (n = 10 for wild type TRPM4 channels and n = 12 for C1093A mutants).

Overexpression of TRPM4 Increases H2O2-dependent Cell Death

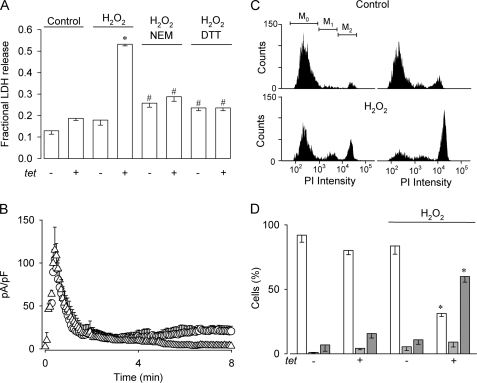

To study whether a persistent, non-desensitizing TRPM4-mediated current would have an impact on cell viability, we measured LDH release of HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells subjected to H2O2. To that purpose, cells were incubated with 200 μm H2O2 for 4 h and LDH release was assessed 20 h after H2O2 removal. As seen in Fig. 3A, H2O2 did not alter significantly the proportion of live cells in HEK-TRPM4 tet− cells. In contrast, HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells exhibited a significant increase in cell death that was reduced by preincubation with NEM or DTT. As shown in Fig. 3B, the effect of NEM on cell death was correlated with the inhibition by NEM of the effect of H2O2 on TRPM4 currents. The thiol-alkylating agent NEM was used to prevent H2O2-mediated oxidation of cysteine residues. On the other hand, DTT was used to block H2O2-induced thiol modifications, maintaining these groups in a reduced state. To characterize further the H2O2-mediated cell death, flow cytometer experiments were performed. Fig. 3C displays representative histograms of PI incorporation for untreated HEK-TRPM4 tet− and HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells and cells were exposed to 200 μm H2O2 using the same protocol as described for the LDH release experiments. As shown, H2O2 induced an increase in the M2 population (∼5.5-fold) corresponding to necrotic cells along with a decrease in the M0 population (∼2.7-fold), corresponding to live cells, both compared with untreated HEK-TRPM4 tet− and HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells (Fig. 3D). However, the proportion of apoptotic cells (M1) was not affected by H2O2.

FIGURE 3.

Heterologous TRPM4 expression renders HEK 293 cells vulnerable to H2O2-induced cell death. A, bars show the fraction of LDH released (mean ± S.E., n = 3) comparing HEK-TRPM4 tet+ and HEK-TRPM4 tet− cells in the absence or presence of 200 μm H2O2, as well as cells exposed to H2O2 preincubated with 5 mm NEM by 1 h or 5 mm DTT by 3 h. Statistical differences were assessed by ANOVA and Dunns post hoc tests, *, p < 0.05 compared with control conditions, #, p < 0.05 compared with tet+ plus H2O2. B, averaged (mean ± S.E., n = 4 for each condition) time course of TRPM4 whole cell currents recorded at 100 mV in HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells with 600 nm Ca2+ in the pipette solution preincubated with 200 μm NEM for 10 min (△) and 200 μm NEM for 10 min followed with an exposure to 200 μm H2O2 (○). Voltage protocol as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. C, representative PI incorporation histograms of HEK-TRPM4 tet− (top panel, left) and HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells (top panel, right) under control conditions (control) and in the presence of 200 μm H2O2 (H2O2) (bottom panels, left and right, respectively). Cells were analyzed by FACS and markers M0, M1, and M2 indicate live, apoptotic, and necrotic cell populations, respectively. D, bars show the percentage (mean ± S.E.) of live (empty bars), apoptotic (light gray bars), and necrotic (dark gray bars) cells from HEK-TRPM4 tet+ and HEK-TRPM4 tet− cells in the absence or presence of 200 μm H2O2 for 4 h; n = 5 independent experiments as those depicted in C. Cell populations were determined by PI incorporation measured 20 h after the removal of H2O2. Statistical differences were assessed by ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests, *, p < 0.05 against either live or necrotic populations.

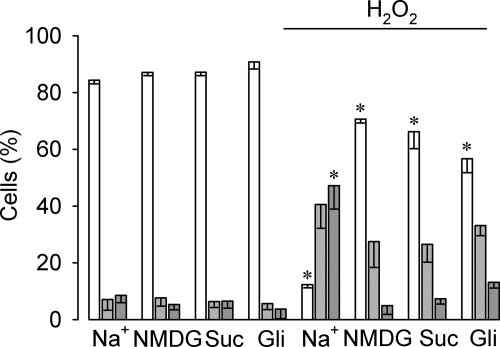

H2O2-induced Cell Death in HeLa Cells

Next, we explored whether native TRPM4 might play a role in H2O2-induced epithelial cell necrosis. Because TRPM4 mRNA has been detected in several cell lines, including HeLa cells (33), we used these cells as a model. To address this issue we performed extracellular cation replacement experiments and evaluated cell viability with flow cytometry upon exposure to H2O2. In contrast to HEK-TRPM4 tet+ cells, HeLa cells appeared to be more resistant to H2O2 and thus, cell death was detected at concentrations ≥0.8 mm (not shown). As depicted in Fig. 4, a 4-h long exposure to 1 mm H2O2 in the presence of extracellular Na+ triggered a ∼7-fold decrease in viable cells, a ∼5.7-fold increase in apoptotic cells, and a ∼9-fold increase in the necrotic population. Extracellular Na+ replacement by the impermeant cation N-methyl-d-glucamine or sucrose during H2O2 exposure reduced the necrotic (M2) population to control values, yet the apoptotic (M1) population did not differ significantly from that observed under conditions of normal extracellular Na+. In line with these results, the unspecific TRPM4 blocker glibenclamide decreased H2O2-induced necrotic cell death.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of extracellular Na+ and glibenclamide on H2O2-induced cell death in HeLa cells. Bars show the percentage (mean ± S.E., n = 3) of live (empty bars), apoptotic (light gray bars), and necrotic (dark gray bars) HeLa wild type cells in the absence or presence of 1 mm H2O2 for 4 h. Cells were cultured in DMEM with normal extracellular NaCl or modified DMEM (Na+-free) in which NaCl was replaced with N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG)-Cl or sucrose (suc). For the glibenclamide experiments, the drug (100 μm) was added to the medium 1 h before H2O2 addition and maintained throughout the entire experiment. Cell populations were determined by PI incorporation and measured 20 h after H2O2 removal. Statistical differences were assessed by ANOVA and Dunns post hoc tests, *, p < 0.05 against either live or necrotic populations.

TRPM4 Is Important for H2O2-induced Necrosis in HeLa Cells

Because of the lack of specific pharmacological tools available to block TRPM4 as well as to rule out the participation of other ROS-sensitive TRPM4-related channels, such as TRPM2 and TRPM7 in H2O2-induced necrosis in HeLa cells, the participation of endogenous TRPM4 channels in cell death was explored by knocking down the expression of TRPM4 with RNAi tools. For that purpose, HeLa cell lines stably expressing a shRNA against TRPM4 (shRNA-TRPM4) or a scramble sequence (shRNA-SS) (24) were generated. To test the efficiency and specificity of the shRNA, we conducted qPCR experiments. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, expression of TRPM4 was reduced by ∼80% in shRNA-TRPM4 cells compared with cells transfected with shRNA-SS. Additionally, shRNA-TRPM4 proved to be specific for TRPM4 as observed by the lack of effect on TRPM2 and TRPM7 transcripts.

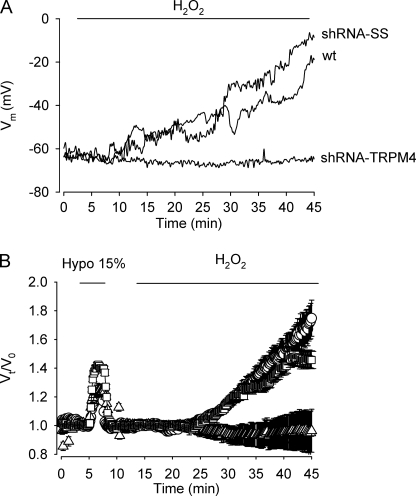

Given that a persistent activity of nonselective cation channels would eventually reduce membrane potential, we studied the effect of H2O2 on the membrane potential in HeLa cells. To that end, current clamp recordings were performed. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, the resting membrane potential of wild type, shRNA-SS, and shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells under basal conditions were similar, however, upon continuous exposure to 1 mm H2O2, shRNA-SS HeLa cells as well as wild type HeLa cells gradually depolarized reaching values close to 0 mV. In contrast, shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells maintained their resting membrane potential. The progressive collapse of the membrane potential observed in wild type and shRNA-SS HeLa cells exposed to H2O2 was paralleled by a significant increase in cell volume (Fig. 5B). Loss of membrane potential and thus, normal ion gradients would have a profound impact on cell function, particularly cell viability. Therefore, if TRPM4 plays a role in H2O2-induced necrosis, it can be anticipated that shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells would become relatively resistant to H2O2. As shown in Fig. 6A, necrosis was significantly (∼3.6-fold) reduced in shRNA-TRPM4 cells compared with wild type or shRNA-SS cells and not significantly different from necrosis detected in untreated shRNA-TRPM4 cells. In contrast, H2O2-induced apoptosis remained unaffected in shRNA-TRPM4 cells. To define whether the reduction in cell viability observed after H2O2 exposure is caspase-dependent, a generic caspase inhibitor was used. As depicted in Fig. 6B, the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD exerted its effect by mainly reducing H2O2-induced apoptosis in wild type and shRNA-SS cells. However, in shRNA-TRPM4 cells, Z-VAD was protected from H2O2-induced apoptosis and, to a lesser extent necrosis.

FIGURE 5.

TRPM4 participates in H2O2-induced cell depolarization and volume increase. A, representative current clamp recording of WT, shRNA-SS, and shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells exposed to 1 mm H2O2. B, experiments showing the effect of 1 mm H2O2 on cell volume in shRNA-SS HeLa cells (circles), shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells (triangles), and WT HeLa cells (squares). For calibration purposes, cells were briefly exposed to a 15% hypotonic solution. Each point represents the mean ± S.E. of values obtained from 12 to 15 cells (n = 4 independent experiments).

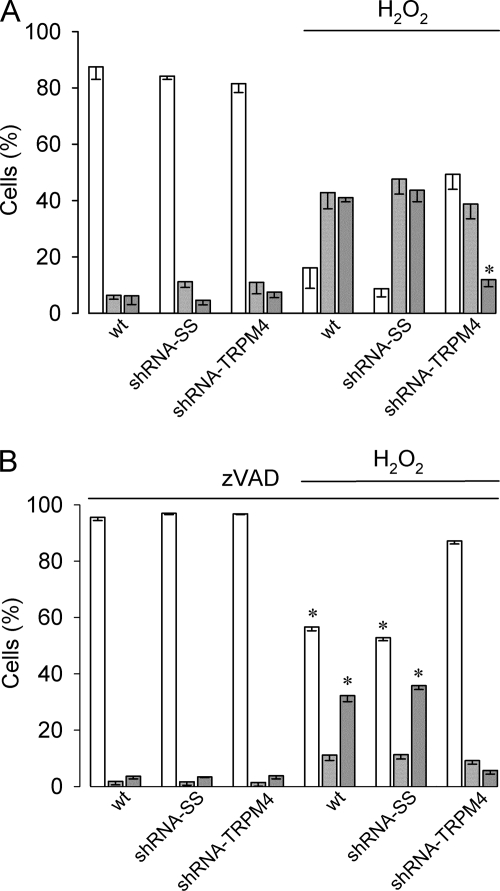

FIGURE 6.

Interference RNA against TRPM4 protects HeLa cells from H2O2-induced necrotic cell death. A, bars show the percentage (mean ± S.E., n = 9) of live (empty bars), apoptotic (light gray bars), and necrotic (dark gray bars) cells from wild type HeLa cells and HeLa cell clones stably expressing shRNA-SS (shRNA-SS) and shRNA-TRPM4 (shRNA-TRPM4) cultured in the absence or presence of 1 mm H2O2 for 4 h. Cell populations were determined by PI incorporation and measured 20 h after H2O2 removal. Statistical differences were assessed by ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests, *, p < 0.05 indicates a significant change respect to necrosis in wild type (wt) and TRPM4-SS (TRPM4-SS) cells in the presence of H2O2. B, same experiment described in A except that cells were preincubated (1 h) and maintained throughout with Z-VAD (10 μm), mean ± S.E., n = 6. Statistical differences were assessed by ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests, *, p < 0.05 against either live or necrotic populations.

Re-expression of TRPM4 Sensitizes HeLa Cells to H2O2-induced Necrosis

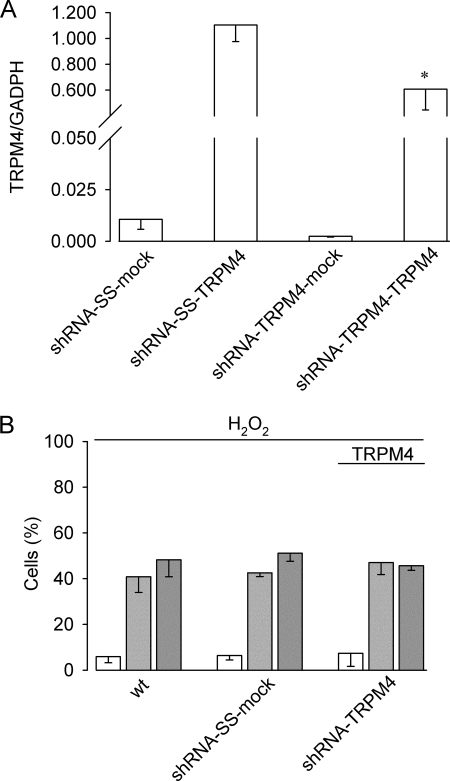

To prove that TRPM4 expression is sufficient to sustain H2O2-induced necrosis in HeLa cells and to discard siRNA off-target effects, shRNA-TRPM4, shRNA-SS, and wild type HeLa cells were acutely transfected with a cDNA-hTRPM4 expression plasmid or mock transfected with an empty plasmid. Because we used a non-mutated hTRPM4 cDNA, we determined first the efficiency of re-expression of the mRNA. As shown in Fig. 7A, acute transfection of the hTRPM4-containing plasmid into shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells restored ∼60% TRPM4 mRNA levels compared with shRNA-SS acutely transfected with the hTRPM4 plasmid. We next exposed the cells to H2O2 and measured PI incorporation. As seen in Fig. 7B, shRNA-TRPM4 cells transfected with TRPM4 were found to be as sensitive as wild type and shRNA-SS cells to H2O2-induced necrosis.

FIGURE 7.

TRPM4 re-expression in TRPM4-deficient HeLa cells re-establishes H2O2-induced necrosis. A, real time quantitative PCR analysis (mean ± S.E., n = 3) of HeLa cell clones stably expressing shRNA-SS or shRNA-TRPM4 transfected with an empty vector (shRNA-SS-mock and shRNA-TRPM4-mock) or the pcDNA4/TO-TRPM4 expression plasmid (shRNA-SS-TRPM4 or shRNA-TRPM4-TRPM4). Data are expressed as relative levels to GADPH transcript. Statistical differences were assessed by Student't t test, *, p < 0.05. B, bars show the percentage (mean ± S.E., n = 4) of live (empty bars), apoptotic (light gray bars), and necrotic (dark gray bars) of wt HeLa cells, shRNA-SS (shRNA-SS-mock) and shRNA-TRPM4 (shRNA-TRPM4) HeLa cell clones cultured in the presence of 1 mm H2O2 for 4 h. shRNA cells were transfected with the pcDNA4/TO-TRPM4 expression plasmid 48 h before the experiment.

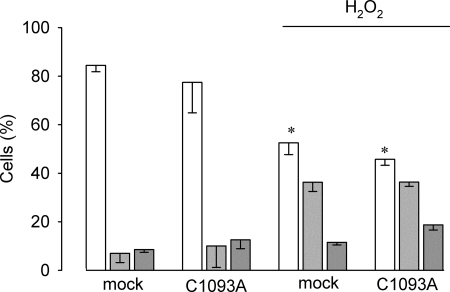

Finally, we tested whether shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells transfected with a plasmid encoding the C1093A mutation would remain insensitive to H2O2-induced necrotic cell death. As depicted in Fig. 8 transient transfection of shRNA-TRPM4 cells with the mutated TRPM4 did not restore vulnerability to H2O2-induced necrotic cell death.

FIGURE 8.

TRPM4-C1093A expression in TRPM4-deficient HeLa cells does not re-establish H2O2-induced necrosis. shRNA-TRPM4 cells were transiently transfected with empty plasmid (mock) or a plasmid containing the mutated (C1093A) version of TRPM4. Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 1 mm H2O2 for 4 h. Bars show the percentage (mean ± S.E., n = 4) of live (empty bars), apoptotic (light gray bars), and necrotic (dark gray bars). Statistical differences were assessed by ANOVA, *, < 0.05 against either live or necrotic populations.

DISCUSSION

Necrosis is hallmarked by a non-compensated increase in cell volume, in part due to unregulated osmotically driven water flux. Although several studies have shown that Na+ permeability is increased in various cell types under oxidative stress, the molecular identity of the channel(s) responsible remain unknown. In the present work we show that H2O2-induced necrotic cell death in HEK 293 and HeLa cells is dependent on the expression and activity of TRPM4. The experiments reported here indicate that H2O2 abolishes, in a concentration-dependent manner, the desensitization usually observed for heterologously expressed TRPM4 channels, giving rise to a sustained current.

The effect of H2O2 on TRPM4 was prevented by DTT and thiol-alkylating agents, suggesting the involvement of cysteine residues in this phenomenon. Reversible oxidation of cysteine side chains to sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH) and its wide ranging biological relevance has come into view during the last decade (34) (for review, see Ref. 35). Using functional site profiling and electrostatic analysis, Salsbury et al. (36) identified common features found in redox-sensitive cysteine residues. We hypothesized that Cys1093 could be a putative redox-modifiable cysteine residue due to its close proximity to a proline residue (Pro1096) and several arginine residues (Arg1090, Arg1094, and Arg1095) that may lower the pKa of Cys1093, enhancing its reactivity to ROS (36). As reported here, H2O2 specifically modulates channel desensitization, yet does not affect channel activation as the sustained current induced by H2O2 remains strictly dependent on Ca2+. TRPM4 desensitization has been related to PI(4,5)P2 depletion (7). Our results show that PI(4,5)P2 is able to rescue from desensitization both the wild type TRPM4, as well as the C1093A mutated TRPM4 channels, suggesting that the effect of H2O2 is likely to be independent of PI(4,5)P2. Although a definitive demonstration of the mechanisms for H2O2 action remains to be settled, a plausible interpretation of our data is that redox modifications of this residue could increase CaM binding to the channel, therefore reducing current desensitization.

The involvement of TRP channels in hypoxia/reperfusion-mediated damage is not without precedent. In smooth muscle cells of the pulmonary artery, hypoxia has been shown to augment several times TRPC1 and TRPC6 mRNA and protein levels (37, 38). Increased oxidative stress levels are associated with reperfusion and evidence suggests that Ca2+ influx via redox-modulated TRP channels is a relevant mechanism through which oxidative stress mediates cell death. TRPM7, a member of the TRPM subfamily, was associated with oxygen glucose deprivation currents in cortical neurons and its suppression prevented anoxic death (39). Furthermore, TRPM2 was found to be activated by micromolar levels of H2O2 through a cADPR-dependent mechanism (40, 41). In contrast to TRPM2 and TRPM7, which are ROS-sensitive and known to participate in cell death, TRPM4 is Ca2+-impermeant cation channel and thus, its effects on cell death cannot be simply explained by Ca2+ influx and subsequent intracellular Ca2+ overload. Of note, overexpression of TRPM4 in COS-7 cells was found to render these cells susceptible to oncotic cell death in the absence of ATP (21), a phenomenon that could be additionally explained in view of our results by the direct effect of H2O2 on TRPM4 activity.

The effect of H2O2 on TRPM4 currents was accompanied with a substantial increase mainly in H2O2-mediated necrosis in HEK 293 cells. At variance, H2O2 induced both apoptosis and necrosis cell death in HeLa cells that endogenously express TRPM4 and exhibited both, apoptosis and necrosis. However, only necrosis was found to be dependent on the extracellular cation. Sodium removal and replacement with non-permeant cations significantly decreased necrosis, suggesting that intracellular Na+ overload and thus, cell volume increase is an important factor for H2O2-induced necrosis in HeLa cells. In line with this finding, H2O2-induced necrosis but not apoptosis was prevented in HeLa cells stably expressing a shRNA against TRPM4. Of note, the generic caspase inhibitor Z-VAD in addition to reducing apoptosis, also decreased H2O2-induced necrosis in shRNA-TRPM4 cells, reflecting a caspase-dependent component of necrosis (42). Consistent with a sustained activity of a non-selective cation channel, H2O2 induced a significant cell depolarization in both wild type and shRNA-SS HeLa cells, whereas shRNA-TRPM4 HeLa cells maintained a normal resting potential. Thus, we propose that prolonged activity of TRPM4 channels plays a significant role in oxidative stress-mediated changes of membrane potential and transmembrane ionic gradients contributing to necrotic cell death.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Heidi Pérez for technical assistance and P. Launay for kindly providing the pcDNA4/TO-FLAG human TRPM4 plasmid, as well as Finn Jørgensen and Luis F. Barros for suggestions and critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by Grant 15010006 from FONDAP (Fondo de Financiamiento de Centros de Excelencia en Investigación), Chile.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- TRP

- transient receptor potential

- TRPM4

- transient receptor potential channel melastatin 4

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- PI(4,5)P2

- phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

- PI

- propidium iodide

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- BAPTA

- 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxyl)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- HEDTA

- N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediaminetriacetic acid

- Z

- benzyloxycarbonyl

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Venkatachalam K., Montell C. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 387–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller B. A. (2006) J. Membr. Biol. 209, 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Launay P., Fleig A., Perraud A. L., Scharenberg A. M., Penner R., Kinet J. P. (2002) Cell 109, 397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilius B., Prenen J., Droogmans G., Voets T., Vennekens R., Freichel M., Wissenbach U., Flockerzi V. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30813–30820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilius B., Prenen J., Voets T., Droogmans G. (2004) Pflügers Arch. 448, 70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmann T., Chubanov V., Gudermann T., Montell C. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 1153–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z., Okawa H., Wang Y., Liman E. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39185–39192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilius B., Mahieu F., Prenen J., Janssens A., Owsianik G., Vennekens R., Voets T. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 467–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen M., Simard J. M. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 6512–6521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen O. H. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, R520–R522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue M., Fujishiro N., Imanaga I. (1999) J. Physiol. 519, 385–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlenker T., Feranchak A. P., Schwake L., Stremmel W., Roman R. M., Fitz J. G. (2000) Gastroenterology 118, 395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koliwad S. K., Kunze D. L., Elliott S. J. (1996) J. Physiol. 491, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herson P. S., Ashford M. L. (1997) J. Physiol. 501, 59–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barros L. F., Stutzin A., Calixto A., Catalán M., Castro J., Hetz C., Hermosilla T. (2001) Hepatology 33, 114–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeulin C., Dazy A. C., Marano F. (2002) Pflügers Arch. 443, 574–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon F., Varela D., Eguiguren A. L., Díaz L. F., Sala F., Stutzin A. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C963–C970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barros L. F., Hermosilla T., Castro J. (2001) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 130, 401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okada Y., Maeno E., Shimizu T., Dezaki K., Wang J., Morishima S. (2001) J. Physiol. 532, 3–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang D., Bhatta S., Gerzanich V., Simard J. M. (2007) Neurosurg. Focus 22, E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerzanich V., Woo S. K., Vennekens R., Tsymbalyuk O., Ivanova S., Ivanov A., Geng Z., Chen Z., Nilius B., Flockerzi V., Freichel M., Simard J. M. (2009) Nat. Med. 15, 185–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simard J. M., Chen M., Tarasov K. V., Bhatta S., Ivanova S., Melnitchenko L., Tsymbalyuk N., West G. A., Gerzanich V. (2006) Nat. Med. 12, 433–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brummelkamp T. R., Bernards R., Agami R. (2002) Science 296, 550–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Launay P., Cheng H., Srivatsan S., Penner R., Fleig A., Kinet J. P. (2004) Science 306, 1374–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonfria E., Murdock P. R., Cusdin F. S., Benham C. D., Kelsell R. E., McNulty S. (2006) J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res. 26, 159–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hetz C., Bono M. R., Barros L. F., Lagos R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 2696–2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowe W. E., Altamirano J., Huerto L., Alvarez-Leefmans F. J. (1995) Neuroscience 69, 283–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stutzin A., Torres R., Oporto M., Pacheco P., Eguiguren A. L., Cid L. P., Sepúlveda F. V. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 277, C392–C402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilius B., Prenen J., Tang J., Wang C., Owsianik G., Janssens A., Voets T., Zhu M. X. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6423–6433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varela D., Simon F., Riveros A., Jørgensen F., Stutzin A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13301–13304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guinamard R., Demion M., Magaud C., Potreau D., Bois P. (2006) Hypertension 48, 587–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prawitt D., Monteilh-Zoller M. K., Brixel L., Spangenberg C., Zabel B., Fleig A., Penner R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15166–15171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Claiborne A., Yeh J. I., Mallett T. C., Luba J., Crane E. J., 3rd, Charrier V., Parsonage D. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 15407–15416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poole L. B., Karplus P. A., Claiborne A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 44, 325–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salsbury F. R., Jr., Knutson S. T., Poole L. B., Fetrow J. S. (2008) Protein Sci. 17, 299–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J., Weigand L., Lu W., Sylvester J. T., Semenza G. L., Shimoda L. A. (2006) Circ. Res. 98, 1528–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin M. J., Leung G. P., Zhang W. M., Yang X. R., Yip K. P., Tse C. M., Sham J. S. (2004) Circ. Res. 95, 496–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aarts M., Iihara K., Wei W. L., Xiong Z. G., Arundine M., Cerwinski W., MacDonald J. F., Tymianski M. (2003) Cell 115, 863–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hara Y., Wakamori M., Ishii M., Maeno E., Nishida M., Yoshida T., Yamada H., Shimizu S., Mori E., Kudoh J., Shimizu N., Kurose H., Okada Y., Imoto K., Mori Y. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolisek M., Beck A., Fleig A., Penner R. (2005) Mol. Cell 18, 61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galluzzi L., Maiuri M. C., Vitale I., Zischka H., Castedo M., Zitvogel L., Kroemer G. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14, 1237–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]