Abstract

Casein kinase 2 (CK2) is a typical serine/threonine kinase consisting of α and β subunits and has been implicated in many cellular and developmental processes. In this study, we demonstrate that CK2 is a positive regulator of the Hedgehog (Hh) signal transduction pathway. We found that inactivation of CK2 by CK2β RNAi enhances the loss-of-Hh wing phenotype induced by a dominant negative form of Smoothened (Smo). CK2β RNAi attenuates Hh-induced Smo accumulation and down-regulates Hh target gene expression, whereas increasing CK2 activity by coexpressing CK2α and CK2β increases Smo accumulation and induces ectopic Hh target gene expression. We identified the serine residues in Smo that can be phosphorylated by CK2 in vitro. Mutating these serine residues attenuates the ability of Smo to transduce high level Hh signaling activity in vivo. Furthermore, we found that CK2 plays an additional positive role downstream of Smo by regulating the stability of full-length Cubitus interruptus (Ci). CK2β RNAi promotes Ci degradation whereas coexpressing CK2α and CK2β increases the half-life of Ci. We showed that CK2 prevents Ci ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Thus, CK2 promotes Hh signaling activity by regulating multiple pathway components.

Keywords: Development, G Protein-coupled Receptor (GPCR), Phosphorylation Enzymes, Signal Transduction, Transcription Factors, CK2, Ci, Hh, Smo

Introduction

The Hedgehog (Hh)3 pathway is one of the major signaling pathways that control animal development. Hh signaling has also been implicated in stem cell maintenance and tissue regeneration and repair, and its malfunction causes several types of cancer (1, 2). The Hh signal is transduced through a reception system at the plasma membrane that includes the receptor complexes Patched (Ptc)-Ihog and the signal transducer Smoothened (Smo) (3–5). Binding of Hh to Ptc-Ihog relieves the inhibition of Smo by Ptc, which allows Smo to activate the Cubitus interruptus (Ci)/Gli family of zinc finger transcription factors. In the past three decades, many Hh pathway components have been identified, including those that control sending, propagating, receiving, and transducing the Hh signal. Among these components, multiple kinases have been identified to play either positive, negative, or dual roles in transducing the Hh signal (6). In Drosophila, the absence of Hh allows the full-length Ci to undergo proteolytic processing to generate a truncated form, Ci75, which blocks the expression of Hh-responsive genes such as decapentaplegic (dpp) (7, 8). Ci processing requires extensive phosphorylation by multiple kinases, including PKA, GSK3, and members of CK1 family (9), which promotes Ci binding to the SCF ubiquitin ligase containing the F-box protein Slimb (10, 11). Efficient phosphorylation of Ci requires the kinesin-like protein Costal 2 that functions as a molecular scaffold to bring Ci and its kinases in close proximity (12). Hh signaling leads to the inhibition of Ci processing by dissociating the Costal 2-Ci kinase complex (12). The seven-transmembrane protein Smo belongs to the serpentine family of G protein-coupled receptors. Interestingly, Smo activation by Hh also requires phosphorylation by PKA and CK1 (13–15). Phosphorylation of Smo promotes its cell surface accumulation (14–16) and induces dimerization of its C-terminal cytoplasmic tail (17). In addition, it has been shown that G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 has a positive role in Hh signaling (18, 19) by regulating Smo through kinase-dependent and kinase-independent mechanisms (20).

Casein kinase 2 (CK2) is a ubiquitously expressed and highly conserved Ser/Thr kinase participating in a wide variety of cellular processes and is frequently activated in human cancers. It is a stable tetrameric complex consisting of two catalytic α subunits and two regulatory β subunits. CK2 holoenzyme normally phosphorylates Ser/Thr at a consensus sequence of E/D/X-S/T-D/E/X-E/D/X-E/D-E/D/X, and its β subunits play a role in anchoring substrates (21). It has been shown that CK2 phosphorylates components in a variety of signaling pathways including Wnt, Akt, and NFκB pathways. However, it is unknown whether CK2 is involved in Hh signal transduction.

It has been shown that that the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of Smo has 26 Ser/Thr sites phosphorylated in response to Hh (15). Several phosphorylated sites in the Smo C-terminal cytoplasmic tail match the consensus of CK2 sites (see below); however, the link among CK2, Smo phosphorylation, and Hh signaling is lacking. In this study, we find that Smo is indeed phosphorylated by CK2 at multiple Ser residues in the Smo C-terminal cytoplasmic tail. Mutating these CK2 sites in Smo attenuates the ability of Smo to rescue the smo−/− phenotype fully. We also find that CK2 is required for Hh-induced Smo accumulation as knockdown of CK2β by RNAi blocked the accumulation Smo that is induced by Hh in wing discs. In contrast, overexpressing CK2α with CK2β enhances Smo phosphorylation and elevates Smo levels. We also find that CK2 has an additional positive role in Hh signaling downstream of Smo by regulating the stability of Ci. We further provide evidence that CK2 regulates Ci by preventing its ubiquitination and thus attenuating its degradation through the proteasome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly Mutants and Transgenes

CK2αTik bears the M161K mutation in its catalytic loop thus homozygous lethal (22). smo3 is a null allele (23). Flies of C765-Gal4; ptc-Gal4, MS1096 Gal4, act>CD2>Gal4, ap-Gal4, GMR-Gal4, UAS-HA-Ci, UAS-HA-Ci-3P, UAS-Smo-PKA12, UAS-Myc-Gli1, UAS-Myc-Gli2, UAS-Dicer, have been described (Flybase) (14, 24–27). The making of attB-UAST and attB-UAST-Myc-Smo constructs and the generation of transgenes at 75B1 attP locus (resulting VK5 lines) have been described (25). CK2 site-mutated Smo variants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis, and their transgenes were generated at 75B1 attP locus resulting series of VK5 lines. For the rescue experiment, tubulinα promoter was inserted in between NotI and Asp-718 sites of attB-UAST upstream of Smo cDNA fragment containing 5′- and 3′-UTR, and VK5 lines were generated. Genotypes for generating smo clones were smo clones expressing VK5-Smo variants, yw MS1096 hsp-flp/+ or Y; smo3 FRT40/hs-GFP FRT40; UAS-VK5-Myc-Smo variants or UAS-VK5-tub-Smo variants; smo clones expressing UAS-HA-Ci or coexpressing UAS-HA-Ci with UAS-FLAG-CK2α and UAS-FLAG-CK2β, y MS1096 hsp-flp1/yw or Y; smo3 FRT40/hs-GFP FRT40; UAS-HA-Ci or UAS-HA-Ci with UAS-FLAG-CK2α+β/hh-lacZ. To construct UAS-CK2βRNAi, a genomic DNA fragment with coding sequence for CK2β nucleotide 91–239 was cloned into pUAST with the corresponding cDNA fragment inserted into a reverse orientation. UAS-CK2βRNAi transgenes were generated by standard P-element-mediated transformation. Multiple independent transformants were generated and examined. Additional Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC) CK2β RNAi lines were ordered, including v32377, v32378, and v106845. The results from VDRC CK2β RNAi lines were consistent with those from the CK2β RNAi lines generated by ourselves. UAST-FLAG-CK2α and UAST-FLAG-CK2β were generated by subcloning the cDNA fragments into the pUAST-FLAG vector, and their transformants were generated with P-element-mediated protocol. UAS-CK2β and UAS-FLAG-CK2β behave similarly in this study. For Figs. 2 M–M″, 2N–N′, and 4A–A′, a recombinant of CK2α and CK2β on the third chromosome was used. The activity of this recombinant is much weaker than other combinations with CK2α and CK2β on either the second or the third chromosomes. In Fig. 2L–L", the strong CK2α and CK2β combination was used.

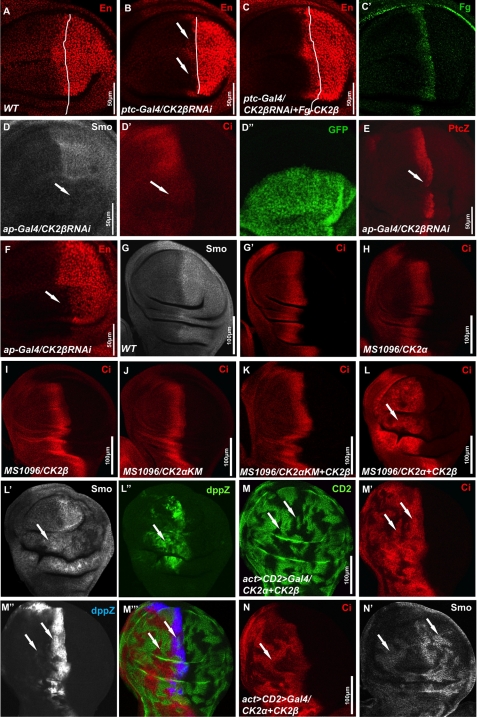

FIGURE 2.

CK2 stabilizes Smo and Ci and up-regulates Hh target gene expression. A, wild-type (WT) wing disc was stained with anti-En antibody. B, wing disc expressing UAS-CK2βRNAi by ptc-Gal4 was stained for En. C and C′, wing disc coexpressing UAS-CK2βRNAi with UAS-CK2β by ptc-Gal4 was stained for En (C) and FLAG (C′). White lines in A–C indicate the A/P boundaries that are defined by Ci staining (data not shown). D–F, wing discs coexpressing UAS-CK2βRNAi with UAS-GFP by ap-Gal4 were stained for Smo (D), Ci (D′), Ptc-lacZ (E), or En (F). GFP expression in D″ marks the RNAi cells. G and G′, wild-type wing imaginal disc was immunostained for endogenous Smo and Ci. H–K, wing discs from flies expressing UAS-FLAG-CK2α (H), UAS-FLAG-CK2β (I), UAS-FLAG-CK2αKM (J), or UAS-FLAG-CK2αKM plus UAS-CK2β (K) by MS1096 Gal4 were stained for Ci. L–L″, wing disc coexpressing UAS-FLAG-CK2α with UAS-CK2β by MS1096 Gal4 was stained for Ci, Smo, and dpp-lacZ. M–N′, wing discs coexpressing UAS-FLAG-CK2α with UAS-CK2β by act>CD2>Gal4 were stained for CD2 (green), Ci (red), Dpp-lacZ (blue), or Smo (gray). Clones were marked by the lack of CD2 staining (M) or by the elevation of Ci (N). Arrows in M′ and N indicate the stabilization of Ci, arrows in M″ indicate the elevated dpp-lacZ expression, and arrows in N′ indicate the accumulation of Smo in both A- and P-compartment cells that was induced by overexpressing CK2α with CK2β. All wing imaginal discs shown in this study were oriented with anterior on the left and ventral on the top.

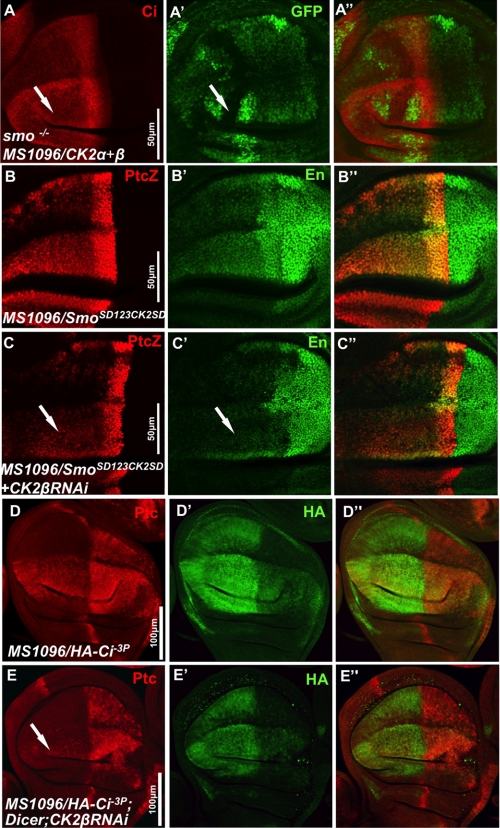

FIGURE 4.

CK2 has an additional role downstream of Smo in Hh pathway. A–A″, wing disc bearing smo clones and expressing FLAG-CK2α and FLAG-CK2β by MS1096 Gal4 stained to show the expression of GFP and Ci. Arrow in A′ indicates a smo clone that is marked by the lack of GFP expression. B–C″, wing discs expressing VK5-Myc-SmoSD123CK2SD alone or along with CK2βRNAi by MS1096 Gal4 immunostained for ptc-lacZ and En. D–E″, wing discs expressing UAS-HA-Ci-3P alone or along with UAS-Dicer and UAS-CK2βRNAi by MS1096 Gal4 immunostained for Ptc and HA.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

For the in vitro kinase assay, GST-Smo and GST-SmoCK2SA fusion proteins containing the fragment of Smo amino acids 808–899 were expressed in bacteria and purified with standard protocols. Ser-114 of GST was mutated to Ala to abolish background phosphorylation by CK2. All of the five CK2 sites in Smo (Ser-816, Ser-817, Ser-818, Ser-819, and Ser-843) were mutated into Ala in GST-SmoCK2SA. The purified fusion proteins were subjected to a kinase assay with commercial CK2 kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP followed by autoradiography.

Cell Culture, Transfection, Immunoprecipitation, Western Blotting, and in Vivo Ubiquitination Assay

S2 cells were cultured as described (28). Transfection was carried out using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen). Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis were performed with standard protocol. CK2β dsRNA was synthesized against the region of nucleotide 91–239 of CK2β cDNA coding sequence. HIB dsRNA, Debra dsRNA, and Hyd dsRNA were synthesized against the regions of nucleotides 397–1089, 121–729, and 181–810, respectively. GFP dsRNA synthesis and the method of treating S2 cells with dsRNAs have been described (28). The uses of cycloheximide (Sigma), okadaic acid (OA) (Calbiochem), and MG132 (Calbiochem) have been described (25, 28). TBB (Calbiochem) treatment was used to inhibit CK2 activity at a final concentration of 40 μm for 4 h before harvesting the cells. Myc-Smo, Myc-Ci, HA-Ci, HA-Cim1–6, and FLAG-HIB constructs have been described (28, 29). An amount of 1/5 CK2α or CK2β cDNA were used when cotransfecting with Myc-Smo, Myc-Ci, or HA-Ci. FLAG-Debra was constructed by inserting the full-length cDNA coding sequence (LD26519) into 2×FLAG-UAST vector. FLAG-Hyd-S was constructed by subcloning Hyd coding sequence 1–921 (isolated by RT-PCR from fly embryo RNA) into 2×FLAG-UAST. To examine the level of Ci-bound ubiquitin, S2 cells transfected with Myc-Ci were lysed with denaturing buffer (1% SDS, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT) and incubated at 100 °C for 5 min. The lysates were then diluted 10× with regular lysis buffer plus 1.5 mm MgCl2 and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibody, separation with 8% gel, and immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody. For Myc-Gli protein analysis, 25 wing discs were dissected from third instar larvae with a specific genotype, lysed with regular S2 cell lysis buffer, and subjected to direct Western blotting with anti-Myc antibody. Antibodies used in this study were mouse anti-Myc, 9E10 (1:5000; Santa Cruz), anti-CK2β (1:250, Calbiochem), anti-FLAG, M2 (1:10,000; Sigma), anti-β-tubulin (1:2000; DSHB), anti-ubiquitin, P4D1 (1:500; Santa Cruz). For quantification analysis, autoradiography densitometric analysis was performed using Metamorph software. Where appropriate, experimental groups were compared using Student's two-tailed t test, with significance defined as p < 0.05.

Immunostaining

Standard protocol was used for wing and eye imaginal disc immunostaining. Antibodies used in this study were mouse anti-Myc, 9E10 (1:50; Santa Cruz), anti-CK2β (1:50; Calbiochem), anti-FLAG, M2 (1:150; Sigma), anti-SmoN (1:10; DSHB), anti-Ptc (1:10; DSHB), anti-En (1:20; DSHB); rabbit anti-FLAG (1:150; ABR), anti-HA, Y-11 (1:50; Santa Cruz), anti-β-galactosidase (1:1500; Cappel), anti-GFP (1:500; Clontech); rat anti-Ci, 2A (1:10; gift from R. Holmgren). 100 μm MG132 (Calbiochem) in M3 medium (Sigma) was used to treat wing discs for up to 6 h (MG132) before immunostaining.

RESULTS

CK2 Is a Positive Regulator of Hh Signaling

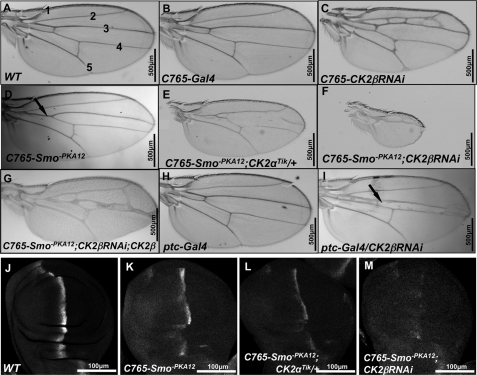

To explore whether CK2 plays a role in Hh signaling, we used a sensitized genetic background to test whether inactivating CK2 could modify the wing phenotype resulted from partial loss of Hh signaling activity. Our previous study indicated that mutating two PKA sites in Smo (Smo-PKA12, Smo-PKA13, or Smo-PKA23) reduced Smo signaling activity and turned Smo into weak dominant negative forms4 (14). Expressing Smo-PKA12 by C765-Gal4 resulted in a reproducible wing phenotype with partial fusion between Vein 3 and Vein 4 (arrow in Fig. 1D), a phenotype similar to that caused by weak fu mutations (30). We reasoned that mutating genes that regulate Smo activity may dominantly modify this phenotype. We found that expressing Smo-PKA12 in the background of CK2α heterozygotes, CK2αTik/+, enhanced the Smo-PKA12 phenotype (Fig. 1E), even though CK2αTik/+ alone produced wild-type wings (not shown). Knockdown of CK2β by RNAi (CK2β RNAi) in Smo-PKA12 expressing wing discs resulted in small wings that consist of anterior- and posterior-most wing structures (Fig. 1F), a phenotype resembling that caused by severe loss of Hh signaling (31), although CK2β RNAi using the C765 driver in otherwise wild-type background did not exhibit loss-of-Hh phenotype (Fig. 1C). Of note, the ectopic veins between Vein 2 and 3 associated with C765-CK2βRNAi could be due to a role of CK2 in the other pathway. Coexpressing FLAG-CK2β with CK2βRNAi in Smo-PKA12-expressing wing discs rescued the small wing phenotype (Fig. 1G), confirming that the loss-of-Hh wing phenotype induced by RNAi was due to the loss of CK2 activity. Furthermore, we found that Hh target gene expression was modified. For example, C765-Smo-PKA12 caused a reduction in ptc expression in A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary (Fig. 1K). Loss of one copy of CK2α further reduced whereas CK2βRNAi nearly abolished ptc expression in C765-Smo-PKA12 background (Fig. 1, L and M).

FIGURE 1.

Inactivation of CK2β produces loss of Hh phenotype in fly adult wing. A, A wild-type (WT) adult wing showing interveins 1–5. B, C765-Gal4 fly with a WT wing. C, wing expressing CK2βRNAi by C765-Gal4. The phenotype assembles the effects of CK2βRNAi on multiple developmental pathways. D, wing from flies expressing Smo-PKA12 by C765-Gal4. E, wing from flies expressing Smo-PKA12 by C765-Gal4 in the background of CK2αTik/+. F, wing coexpressing Smo-PKA12 with CK2βRNAi by C765-Gal4. G, wing coexpressing Smo-PKA12 with CK2βRNAi and CK2β. H, ptc-Gal4 flies with WT wings. I, adult wing expressing CK2βRNAi by ptc-Gal4. J–M, wing discs expressing Smo-PKA12 alone (K), along with CK2αTik/+ (L), or along with CK2βRNAi (M) by C765-Gal4 stained for Ptc.

To explore the role of CK2 in Hh signaling further, we employed CK2 RNAi and overexpression of CK2 in otherwise wild-type background to examine their effects on Hh signaling. We found that knockdown of CK2β by RNAi with ptc-Gal4 inhibited Hh signaling activity, as indicated by attenuated en expression in Hh-responding cells (arrows in Fig. 2B) and fused wing phenotype (arrow in Fig. 1I). Coexpressing FLAG-CK2β with CK2βRNAi rescued en expression (Fig. 2C) and abolished fused wing phenotype (data not shown), indicating that the phenotype observed in Fig. 2B was due to the loss of CK2β. We further found that knockdown of CK2β by RNAi blocked the accumulation of Smo and Ci (Fig. 2, D and D′), attenuated Ptc-lacZ (Fig. 2E), and abolished en expression (Fig. 2F) in A-compartment cells near the A/P boundary when UAS-CK2βRNAi was expressed via the wing-specific ap-Gal4 that expresses Gal4 in the dorsal compartment of the wing disc. These findings suggest that CK2 plays a positive role in Hh signaling likely by stabilizing Smo and Ci.

To investigate the consequence of elevated CK2 activity on Hh signaling in vivo, we coexpressed the catalytic α-subunit and the regulatory β-subunit of CK2 using the wing-specific Gal4 driver, MS1096, that expresses Gal4 in the whole wing pouch (with the dorsal compartment exhibiting stronger expression than the ventral compartment) (26). We found that expressing CK2α or CK2β alone had no effect on the levels of Ci (Fig. 2, H and I) and did not cause any change in Hh target gene expression (not shown). However, coexpressing CK2α with CK2β dramatically elevated the levels of Ci (Fig. 2L), highly accumulated Smo (Fig. 2L′), and ectopically induced dpp expression (Fig. 2L″). In contrast, expressing either CK2αKM, a kinase-dead form of CK2α (32), or coexpressing CK2αKM with CK2β did not affect Ci (Fig. 2, J and K) and Smo (data not shown) and had no effects on Hh target gene expression (data not shown), suggesting that the CK2 kinase activity is required for Smo and Ci accumulation and Hh signal transduction. In addition, we found that A-compartment cells overexpressing CK2α with CK2β accumulated Ci (Fig. 2, M′ and N) and Smo (Fig. 2N′) in a cell-autonomous fashion, which elevates dpp expression in cells near the A/P boundary and induces low dpp expression in cells away from the A/P boundary (Fig. 2M″). Taken together, our data indicate that CK2 is a positive regulator of Hh signaling and is required for Smo and Ci accumulation.

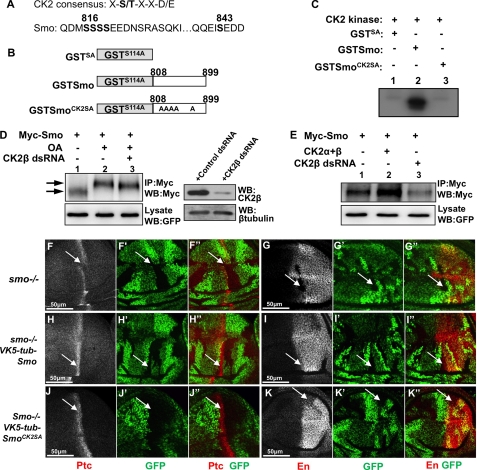

CK2 Regulates Smo Activity by Phosphorylating Multiple Serine Residues in the Smo C-terminal Cytoplasmic Tail

In our previous studies we found that PKA and CK1 site-mutated Smo still showed a mobility shift on the SDS gel and that phosphorylation-mimicking Smo (with PKA and CK1 sites substituted to Asp) showed further cell surface accumulation in response to Hh (14). These observations suggest that Smo is likely phosphorylated at additional sites by unknown kinase(s). Indeed, Zhang et al. showed that Smo was phosphorylated, in response to Hh, at many other sites in addition to the PKA and CK1 sites (15), some of which match the CK2 consensus sites (Fig. 3A) (33). We then asked whether CK2 could be a Smo kinase, and, if so, what role CK2-mediated Smo phosphorylation could play. To determine whether CK2 can phosphorylate Smo directly, we carried out an in vitro kinase assay using purified GST-Smo fusion protein and recombinant CK2. Two GST-Smo fusion proteins were used as substrate: one contains wild-type sequence from amino acids 808–899 (GST-Smo) and the other contains the same region of Smo with all five putative CK2 sites mutated to Ala (GST-SmoCK2SA) (Fig. 3B). To abolish background phosphorylation, we also mutated Ser-114 in GST to Ala, which is a putative CK2 site. As shown in Fig. 3C, GST-Smo was phosphorylated by CK2 (lane 2); mutating five Ser residues in GST-Smo abolished phosphorylation by CK2 (lane 3), suggesting that CK2 can directly phosphorylate these Ser residues.

FIGURE 3.

Smo is phosphorylated by CK2. A, CK2 consensus sequence and Smo sequence indicating putative CK2 phosphorylation sites. B, schematic drawing of GST-Smo constructs that were expressed in bacteria. C, CK2 phosphorylates Smo in vitro. Shown here is an in vitro kinase assay by using the purified GST-Smo fusion proteins and the commercial CK2 kinase. D, S2 cells transfected with Myc-Smo and treated with OA or with OA and CK2β dsRNA. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated and blotted with anti-Myc antibody to detect Smo phosphorylation indicated by its mobility shift on the SDS gel. Arrow indicates hyperphosphorylated forms of Smo, and arrowhead indicates hypophosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms. GFP served as transfection control. Special lysis buffer containing NaF and Na3VO4 was used to examine Smo phosphorylation. The efficiency of CK2β RNAi is shown in the right panel where β-tubulin served as loading control. E, Myc-Smo transfected into S2 cells either with FLAG-CK2α and FLAG-CK2β or with the treatment of CK2β dsRNA. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc and blotted (WB) with anti-Myc to examine the levels of Smo. Regular lysis buffer was used to examine Smo levels. GFP served as transfection control. F–G′, wing discs carrying smo mutant clones immunostained for Ptc (red), En (red), or GFP (green). H–I′, wing discs containing smo mutant clones and expressing VK5-Myc-Smo by tubulinα promoter immunostained to show Ptc, En, and GFP. J–K′, wing discs containing smo mutant clones and expressing VK5-Myc-SmoCK2SA by tubulinα promoter immunostained to show Ptc, En, and GFP. smo mutant clones are recognized by the lack of GFP expression.

We next turned to cell-based assays to determine whether CK2 regulates Smo phosphorylation and accumulation. S2 cells were transfected with Myc-Smo expression construct alone or together with CK2α and CK2β, or CK2β RNAi. Myc-Smo was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts with an anti-Myc antibody followed by Western blotting with the anti-Myc antibody. Consistent with our previous findings (28), the phosphatase inhibitor OA induced an electronic mobility shift of Myc-Smo, indicative of Smo phosphorylation (Fig. 3D, lane 2, top panel). The OA-induced Smo mobility shift was attenuated by CK2βRNAi (lane 3, top panel) but not by GFP RNAi (data not shown). In addition, we found that, in S2 cells, coexpressing CK2α and CK2β with Myc-Smo accumulated Smo (Fig. 3E, lane 2, compared with lane 1, top panel) whereas knocking down CK2β by RNAi severely decreased Smo (lane 3, compared with lane 1, top panel), which are consistent to the findings in wing discs (Fig. 2, D, L′, and N′). These data indicate that CK2 phosphorylates Smo and regulates Smo accumulation.

We reasoned that if CK2 phosphorylation of Smo promotes Smo activity, mutating the CK2 sites in Smo should attenuate Smo activity. We generated a Myc-tagged Smo mutant construct in which CK2 sites were mutated to Ala (SmoCK2SA). To examine the precise activity of Smo, we generated transgenes at the 75B1 VK5 attP locus, which ensures equal expression of different forms of Smo (25). In addition, we use the tubulinα promoter that drove gene expression at a level close to endogenous gene expression (34). We found that expressing Myc-Smo using the tubulinα promoter (VK5-tub-Myc-Smo) was able to fully rescue ptc and en expression in smo mutant cells (arrows in Fig. 3, H–I″), whereas the expression of VK5-tub-Myc-SmoCK2SA fully rescued ptc but partially rescued en expression (arrows in Fig. 3, J–K″), suggesting that mutating CK2 sites in Smo slightly affected Smo activity. Phosphorylation does not seemingly contribute to all aspects of CK2 regulating Smo because inactivating CK2 caused a dramatic change in Smo levels but mutating the phosphorylation sites in Smo only slightly down-regulates its activity. CK2 could have other role(s) in regulating Smo. In fact, the levels of both Myc-SmoCK2SA and Myc-SmoCK2SD, in which SA mutation blocks phosphorylation and SD mutation mimics phosphorylation, were increased by the overexpression of CK2 and decreased by CK2βRNAi (supplemental Fig. S1).

CK2 Has an Additional Positive Role Downstream of Smo

We found that overexpression of CK2 caused Ci elevation (Fig. 2, L, M′, and N). One possibility is that Ci stabilization is due to ectopic activation of Smo by CK2. However, it is also possible that CK2 may play an additional role downstream of Smo to regulate other pathway component(s) of the Hh pathway such as Ci. To test this, we coexpressed CK2α with CK2β by MS1096 Gal4 in wing discs carrying smo mutant clones induced by FRT/FLP-mediated mitotic recombination. We observed that CK2-induced Ci elevation still persisted in smo mutant cells (arrow in Fig. 4A), indicating that CK2 acts downstream of Smo to induce Ci elevation. We also generated Myc-SmoSD123CK2SD with CK2 sites mutated to Asp (CK2SD) to mimic phosphorylation in the context of SmoSD123 in which the three PKA/CK1 phosphorylation clusters were mutated to Asp (14). VK5-Myc-SmoSD123CK2SD had constitutive signaling activity and induced ectopic ptc-lacZ and en expression (Fig. 4, B and B′). Knockdown of CK2β by RNAi attenuated the ectopic ptc-lacZ expression (arrow in Fig. 4C) and greatly reduced the ectopic en expression (arrow in Fig. 4C′). Similar results were achieved by using act>CD2>Gal4 to generate clones that express Myc-SmoSD123CK2SD with or without CK2βRNAi (supplemental Fig. S2). These data suggest that CK2 might have additional positive role(s) in Hh signaling by regulating Smo through means other than phosphorylating Smo at the sites identified, or by regulating other component(s) downstream of Smo.

We then examined whether CK2 could regulate Ci activity. As shown in Fig. 4D, expression of Ci-3P, a mutant form of Ci in which three PKA sites were mutated to Ala to abolish PKA phosphorylation and thus Ci processing (26), induced high levels of ectopic ptc expression. Coexpression of CK2βRNAi with Ci-3P severely reduced the ectopic ptc expression induced by Ci-3P (arrow in Fig. 4E), suggesting that CK2 positively regulates Ci-3P activity. Of note, the levels of HA-Ci-3P (indicated by HA staining) were significantly reduced by CK2βRNAi, suggesting that CK2 promotes Ci activity by increasing its level.

CK2 Regulates Ci Turnover

One possibility that CK2 increases endogenous Ci levels is to enhance ci transcription. To test this, we monitored ci transcription using ci-lacZ, a ci enhancer trap line that expresses lacZ. We found that coexpressing CK2α and CK2β stabilized Ci without affecting ci-lacZ expression (arrow in Fig. 5A), suggesting that CK2 does not regulate ci transcription.

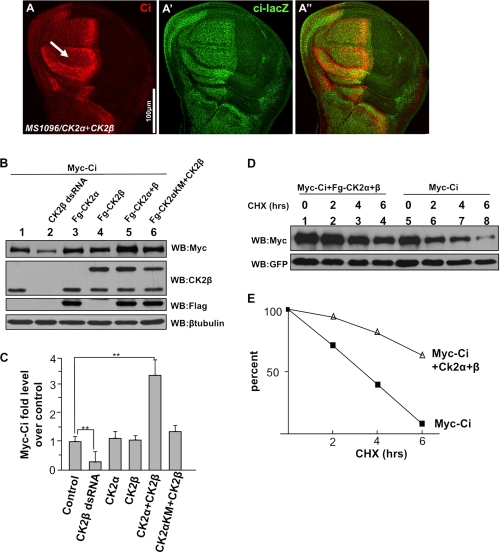

FIGURE 5.

CK2 up-regulates Ci by blocking Ci degradation. A–A″, wing disc coexpressing FLAG-CK2α and FLAG-CK2β immunostained for Ci and Ci-lacZ. Of note, Ci, but not Ci-lacZ, was elevated by CK2. B, CK2 kinase activity required for Ci stabilization. Myc-Ci was transfected into S2 cells with either the indicated CK2 constructs or the treatment of CK2β dsRNA. Cell extracts were subjected to direct Western blotting (WB) with anti-Myc antibody to detect the levels of Myc-Ci, with anti-CK2β antibody to detect the exogenous CK2β expression and the endogenous CK2β level that indicates the efficiency of CK2β RNAi, with anti-FLAG antibody to detect the FLAG-tagged CK2α, with anti-β-tubulin antibody to detect β-tubulin that served as loading control. C, quantification of Myc-Ci relative levels. The level of Ci from cells transfecting Myc-Ci alone was set as 1. **, p < 0.01 (Student's t test). D, S2 cells cotransfected with Myc-Ci and GFP, or with Myc-Ci, GFP, and FLAG-CK2α plus FLAG-CK2β, followed by treatment with cycloheximide for the indicated times. GFP expression served as transfection control. E, quantification of Ci levels from Western blot analysis performed in D. CHX, cycloheximide.

Another possibility is that CK2 might block Ci processing, thus leading to the accumulation of full-length Ci. However, in our in vivo function assay, in which HA-Ci was coexpressed with FLAG-CK2α and CK2β in the P-compartment wing discs carrying smo mutant clones and hh-lacZ reporter gene, we found that P-compartment smo mutant cells coexpressing HA-Ci with CK2α and CK2β fully suppressed hh-lacZ expression, similar to the effect caused by expressing HA-Ci alone (supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that CK2 does not block Ci processing. This is consistent with the finding that HA-Ci-3P was still regulated by CK2.

A third possibility is that CK2 increases Ci levels by regulating its turnover. To test this, we examined whether CK2 regulates the turnover of Ci in cultured S2 cells. We found that Myc-tagged full-length Ci (Myc-Ci) was stabilized by coexpression of FLAG-tagged CK2α and CK2β (Fig. 5B, lane 5, top panel) whereas Myc-Ci levels remained nearly unchanged when coexpressing either FLAG-CK2α or CK2β alone (lanes 3 and 4, top panel). The ability of CK2 to induce Ci stabilization depended on its kinase activity, as coexpressing the kinase-dead FLAG-CK2αKM with FLAG-tagged CK2β did not stabilize Ci (lane 6, top panel). In addition, CK2βRNAi in cultured S2 cells reduced Myc-Ci levels (lane 2, top panel). Fig. 5C shows the quantification of these data. We further carried out a time course experiment to examine Myc-Ci half-life. S2 cells were transfected with Myc-Ci with or without FLAG-tagged CK2α and CK2β, and Myc-Ci protein levels were monitored at different time points after treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide. We found that Myc-Ci was barely detected after 6 h of incubation with cycloheximide (Fig. 5D, lane 8, top panel). In contrast, coexpression of CK2α with CK2β increased the half-life of Myc-Ci (Fig. 5D, E). Taken together, our data support the idea that CK2 regulates Ci activity by preventing its degradation.

CK2 Down-regulates Ci Ubiquitination and Prevents Its Degradation by Proteasome

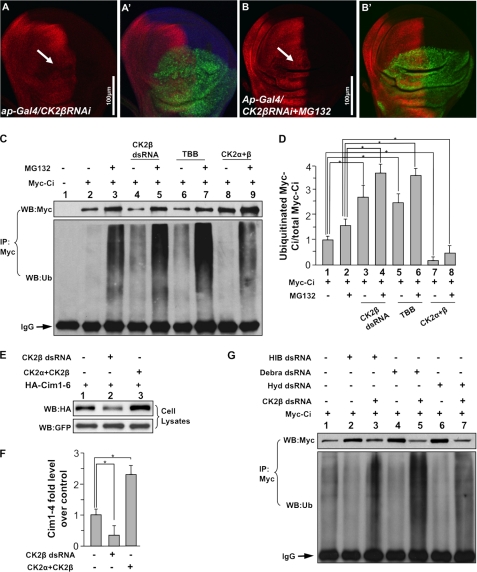

We then determine whether CK2 regulates Ci stability through proteasome. Expressing CK2βRNAi by ap-Gal4 destabilized Ci in dorsal compartment cells of wing discs (arrow in Fig. 6A). However, down-regulation of Ci by CK2βRNAi was prevented by treatment with the proteasome-specific inhibitor MG132 (arrow in Fig. 6B), suggesting that Ci is degraded by proteasome when CK2 is inactivated. As proteasome degrades proteins after they are ubiquitinated, we asked whether CK2 regulates Ci ubiquitination. In S2 cells transfected with Myc-Ci, ubiquitinated Ci could be detectable by Western blot analysis with an anti-ubiquitin antibody following immunoprecipitation of Myc-Ci with a Myc antibody (Fig. 6C, lane 2, bottom panel). MG132 treatment stabilized Myc-Ci and accumulated ubiquitinated Ci (lane 3, top and bottom panel, respectively). CK2βRNAi destabilized Ci but enhanced Ci ubiquitination (lane 4, compared with lane 1, top and bottom panels). Similarly, the treatment of a specific CK2 inhibitor, TBB, down-regulated the levels of Ci but promoted Ci ubiquitination (lane 6 compared with lane 1, top and bottom panels). MG132 treatment further accumulated ubiquitinated Ci that was promoted by either CK2βRNAi or TBB (lane 5 and 7 compared with lane 3, bottom panel). In contrast, overexpressing CK2α with CK2β dramatically stabilized Ci but down-regulated Ci ubiquitination (compare lane 8 with lane 2, and lane 9 with lane 3). Our quantification analysis showed that CK2 decreases the ratio of ubiquitinated Ci versus total Ci (Fig. 6D). These data indicate that CK2 regulates Ci stability through the ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated pathway.

FIGURE 6.

CK2 down-regulates Ci ubiquitination and prevents the proteasome-mediated Ci degradation. A–B′, wing discs expressing UAS-CK2βRNAi by ap-Gal4 were treated with or without MG132 and immunostained for Ci. The treatment of MG132 restored Ci that was down-regulated by CK2β RNAi. GFP marks the RNAi cells. C, CK2 down-regulates Ci ubiquitination. S2 cells were transfected with Myc-Ci and incubated with CK2β dsRNA, or TBB, or cotransfected with FLAG-CK2α and FLAG-CK2β, followed by the treatment with or without MG132. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc antibody and blotted (WB) with anti-Myc antibody to determine the levels of Ci, or blotted with anti-ubiquitin antibody to examine the Ci-bound ubiquitin. IgG served as loading control. D, quantification analysis shows the ratio of ubiquitinated Ci to total Ci in C. Myc-Ci in lane 1 of C was set as 1. *, p < 0.05 (Student's t test). E, Cim1–6, with HIB-interacting sites mutated, is still regulated by CK2. S2 cells were cotransfected with HA-Cim1–6 and GFP, with either CK2α+CK2β or CK2β dsRNA treatment. Cell lysates were subjected to direct Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. F, quantification of HA-Cim1–6 relative levels from E is shown. The level of Cim1–6 from cells transfecting HA-Cim1–6 alone was set as 1. *, p < 0.05 (Student's t test). G, knockdown of the known E3s does not affect Ci ubiquitination that is induced by CK2 inactivation. S2 cells were transfected with Myc-Ci and treated with HIB dsRNA, Debra dsRNA, or Hyd dsRNA, with or without CK2β dsRNA. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and blotted with anti-Myc or anti-ubiquitin antibodies. IgG served as loading control.

It has been reported that multiple E3 ligases regulate Ci stability via the proteasome (35). As CK2 does not regulate Ci processing (supplemental Fig. S3) and Ci-3P, which is no longer regulated by Slimb, is still regulated by CK2 (Fig. 4, E and E′), it is unlikely that CK2 regulates Ci via SCFSlimb/β-Trcp. It has also been shown that other E3 ligases, such as HIB (27, 36), Hyd (37), and Debra (38), are involved in Ci degradation under different circumstances. However, we found that the stability of Cim1–6, a mutant form of Ci that could bypass its regulation by HIB (29), was up-regulated by overexpressing CK2 and down-regulated by CK2βRNAi (Fig. 6, E and F). Furthermore, activation of CK2 did not significantly stabilize Ci in eye discs posterior to the morphogenetic furrow where Ci is degraded by HIB (supplemental Fig. S4) (27, 36). These observations suggest that CK2 may regulate Ci in a manner independent of HIB. RT-PCR analysis indicated that Debra, HIB, and Hyd are expressed in cultured S2 cells (supplemental Fig. S5C). To determine whether CK2 could stabilize Ci by attenuating Ci ubiquitination by the above E3s, Myc-Ci was transfected into S2 cells treated with Debra RNAi, HIB RNAi, or Hyd RNAi, and with or without CK2βRNAi. RNAi efficiencies were examined by Western blotting (supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). Consistent with previous findings (27, 38), RNAi of HIB and Debra down-regulated Ci ubiquitination (Fig. 6G, compare lanes 2 and 4 with lane 1, bottom panel). We also found that RNAi of Hyd attenuated Ci ubiquitination (lane 6). However, knockdown of CK2β by RNAi still elevated Ci ubiquitination even in the presence of RNAi of either HIB (lane 3 compared with lane 2, bottom panel), Debra (lane 5 compared with lane 4, bottom panel), or Hyd (lane 7 compared with lane 6, bottom panel), suggesting that CK2 may regulate Ci ubiquitination and stability through ubiquitin ligase(s) other than the known E3s.

CK2 Regulates Gli Proteins

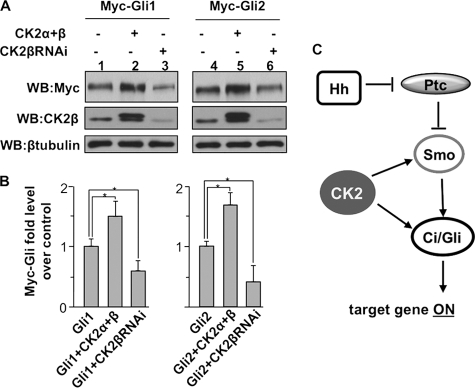

To determine whether CK2 plays similar roles in regulating Gli proteins, we expressed Myc-Gli1 or Gli2 in wing discs expressing either CK2βRNAi or FLAG-CK2α and CK2β. Wing imaginal discs were collected and subjected to direct Western blot analysis with anti-Myc antibody to examine the levels of Gli proteins. We found that expressing FLAG-CK2α and CK2β enhanced the levels of Gli1 and Gli2 (Fig. 7A, lane 2 and 5, compared with lane 1 and 4, respectively) whereas CK2β RNAi decreased both Gli1 and Gli2 (lane 3 and 6, compared with lane 1 and 4, respectively). These data are consistent with the finding of CK2 stabilizing Ci. Taken together, our observations suggest that CK2 may play a conserved role in regulating Ci/Gli stability.

FIGURE 7.

CK2 stabilizes Gli proteins in Drosophila wing imaginal discs. A, Western blot (WB) analysis of protein extracts from wing discs expressing UAS-Myc-Gli1 or UAS-Myc-Gli2, either with UAS-CK2α and UAS-CK2β or with UAS-CK2βRNAi, under the MS1096 Gal4 driver. 25 wing discs were used for each sample. CK2β levels detected by anti-CK2β antibody indicated CK2β RNAi efficiency. β-Tubulin served as loading control. B, quantification analysis of the levels Gli protein from the experiment in A. The levels of Gli1 and Gli2 in lanes 1 and 4 were set as 1, respectively. *, p < 0.05 (Student's t test). C, model for the involvement of CK2 in Hh signaling. CK2 is positively involved in Hh signal transduction by phosphorylating and activating Smo and by preventing Ci ubiquitination thus attenuating its degradation by the proteasome.

DISCUSSION

The regulation of Smo and Ci/Gli is a critical event in Hh signal transduction, and Smo and Ci/Gli are two major targets for developing diagnostic and therapeutic treatments of cancers (2). A comprehensive understanding of Hh signaling at the levels of Smo and Ci/Gli will undoubtedly shed light into the mechanism of Hh in cancer progression and into identification of potential drugs for therapeutic intervention. CK2 has long been shown, in most cases, to act as a positive regulator in different signaling pathways and tumorigenesis. For example, CK2 phosphorylates many transcription factors, proto-oncoproteins, and tumor suppressor proteins, which regulates the access of these proteins to the proteasome (39). However, it is unknown whether CK2 is also involved in Hh signal transduction. In this study, we have identified CK2 as a novel component in Hh signaling. By using both the Drosophila wing imaginal disc and the cultured cells, we provide the first genetic and biochemical evidence for a physiological function of CK2 in Hh signal transduction. In addition, we provide evidence that CK2 exerts multiple roles by regulating both Smo and Ci/Gli. Thus, it would be interesting to determine whether the drugs targeting CK2 could be used as treatments for cancers that are caused by activation of Smo or Ci/Gli.

It has been shown previously that Hh-induced Smo phosphorylation requires PKA and CK1, and Smo phosphorylation promotes its cell surface accumulation and dimerization (4, 40). Here, we show that CK2 acts as an additional kinase to phosphorylate Smo and promote Smo signaling activity, even though the function of CK2 is not as potent as the functions of PKA and CK1. We think that phosphorylation of Smo by CK2 might not be absolutely required for Smo activation but rather plays a fine-tuning role in modulating Smo activity.

Knockdown of CK2β by RNAi in wing discs caused severe reduction of Smo accumulation both in A-compartment cells where there is no Hh and in P-compartment cells where there is Hh stimulation (Fig. 2D). Consistently, CK2βRNAi in cultured S2 cells severely down-regulated Smo levels (Fig. 3E). Coexpressing CK2α with CK2β accumulates Smo in both A- and P-compartment cells (Fig. 2, L′ and N′). However, mutating CK2 sites in Smo did not affect its cell surface accumulation in S2 cells (data not shown), and the levels of Smo mutant forms lacking CK2 phosphorylation or mimicking CK2 phosphorylation were still regulated by CK2 (supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that CK2 may regulate Smo accumulation indirectly through other mechanism(s).

We provide evidence that CK2 regulates Ci stability through the ubiquitination/proteasome pathway; however, the precise mechanism awaits further investigation. It is possible that CK2 regulates Ci stability by directly phosphorylating Ci as sequence analysis identified 14 Ser/Thr residues that confirm CK2 phosphorylation consensus sites (supplemental Fig. S6). However, simultaneously mutating four optimal sites (supplemental Fig. S6) neither affected Ci stability in S2 cells nor changed Ci activity in wing discs (data not shown). CK2 could phosphorylate Ci at other sites. It is also possible that CK2 might regulate component(s) in the ubiquitination/proteasome pathway and thus prevent Ci/Gli degradation, which may account for the ability of CK2 to regulate the stability of many proteins. We found that Ci ubiquitination was up-regulated when CK2 was inactivated. However, knockdown of the known E3 ligases that regulate Ci did not affect Ci ubiquitination induced by CK2 inactivation (Fig. 6G). In addition, the misexpression of CK2 does not phenocopy loss of HIB. For example, overexpressing CK2α with CK2β did not dramatically up-regulate the levels of Ci in posterior cells of the eye discs where HIB plays a major role in degrading Ci in the presence of Hh (supplemental Fig. S4). These data suggest that CK2 may regulate Ci ubiquitination and stability through a novel E3. The identification of such E3 awaits further investigation in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Robert Holmgren for the Ci 2A antibody, Dr. Ravi Allada for the CK2αTik allele, the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center for CK2β RNAi fly strains, Drosophila Genomics Resource Center for cDNA clones, and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies. We also thank Dr. Haining Zhu for help with some of the quantification analysis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM079684 (to J. Jia) and GM067045 and GM061269 (to J. Jiang). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Grant 0830009N (to J. Jia) and Welch Foundation Grant I-1603 (to J. Jiang).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

H. Jia, Y. Liu, R. Xia, and J. Jia, unpublished data.

- Hh

- Hedgehog

- Ci

- Cubitus interruptus

- CK

- casein kinase

- dpp

- decapentaplegic

- OA

- okadaic acid

- Ptc

- Patched

- Smo

- Smoothened

- TBB

- 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole

- DSHB

- Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ingham P. W., McMahon A. P. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 3059–3087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang J., Hui C. C. (2008) Dev. Cell 15, 801–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng X., Mann R. K., Sever N., Beachy P. A. (2010) Genes Dev. 24, 57–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia J., Jiang J. (2006) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1249–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lum L., Beachy P. A. (2004) Science 304, 1755–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aikin R. A., Ayers K. L., Thérond P. P. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 330–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aza-Blanc P., Ramírez-Weber F. A., Laget M. P., Schwartz C., Kornberg T. B. (1997) Cell 89, 1043–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Méthot N., Basler K. (1999) Cell 96, 819–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang J. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2315–2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smelkinson M. G., Kalderon D. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16, 110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia J., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Tong C., Wang B., Hou F., Amanai K., Jiang J. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 819–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W., Zhao Y., Tong C., Wang G., Wang B., Jia J., Jiang J. (2005) Dev. Cell 8, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apionishev S., Katanayeva N. M., Marks S. A., Kalderon D., Tomlinson A. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia J., Tong C., Wang B., Luo L., Jiang J. (2004) Nature 432, 1045–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C., Williams E. H., Guo Y., Lum L., Beachy P. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17900–17907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denef N., Neubüser D., Perez L., Cohen S. M. (2000) Cell 102, 521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y., Tong C., Jiang J. (2007) Nature 450, 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng S., Maier D., Neubueser D., Hipfner D. R. (2010) Dev. Biol. 337, 99–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molnar C., Holguin H., Mayor F., Jr., Ruiz-Gomez A., de Celis J. F. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7963–7968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y., Li S., Tong C., Zhao Y., Wang B., Liu Y., Jia J., Jiang J. (2010) Genes Dev. 24, 2054–2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litchfield D. W. (2003) Biochem. J. 369, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J. M., Kilman V. L., Keegan K., Paddock B., Emery-Le M., Rosbash M., Allada R. (2002) Nature 420, 816–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y., Struhl G. (1998) Development 125, 4943–4948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W., Yang J., Liu Y., Chen X., Yu T., Jia J., Liu C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22649–22656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia H., Liu Y., Yan W., Jia J. (2009) Development 136, 307–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang G., Wang B., Jiang J. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 2828–2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q., Zhang L., Wang B., Ou C. Y., Chien C. T., Jiang J. (2006) Dev. Cell 10, 719–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Cao X., Jiang J., Jia J. (2007) Genes Dev. 21, 1949–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Q., Shi Q., Chen Y., Yue T., Li S., Wang B., Jiang J. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21191–21196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alves G., Limbourg-Bouchon B., Tricoire H., Brissard-Zahraoui J., Lamour-Isnard C., Busson D. (1998) Mech. Dev. 78, 17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basler K., Struhl G. (1994) Nature 368, 208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penner C. G., Wang Z., Litchfield D. W. (1997) J. Cell. Biochem. 64, 525–537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo G. L., Vandenberg M. T., Yu I. J., Bae Y. S., Franza B. R., Jr., Marshak D. R. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 20317–20325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zecca M., Struhl G. (2002) Development 129, 1357–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang J. (2006) Cell Cycle 5, 2457–2463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kent D., Bush E. W., Hooper J. E. (2006) Development 133, 2001–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J. D., Amanai K., Shearn A., Treisman J. E. (2002) Development 129, 5697–5706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dai P., Akimaru H., Ishii S. (2003) Dev. Cell 4, 917–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres J., Pulido R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y., Tong C., Jiang J. (2007) Fly 1, 333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]