Abstract

Alterations in the metabolism of amyloid precursor protein (APP) are believed to play a central role in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Burgeoning data indicate that APP is proteolytically processed in endosomal-autophagic-lysosomal compartments. In this study, we used both in vivo and in vitro paradigms to determine whether alterations in macroautophagy affect APP metabolism. Three mouse models of glycosphingolipid storage diseases, namely Niemann-Pick type C1, GM1 gangliosidosis, and Sandhoff disease, had mTOR-independent increases in the autophagic vacuole (AV)-associated protein, LC3-II, indicative of impaired lysosomal flux. APP C-terminal fragments (APP-CTFs) were also increased in brains of the three mouse models; however, discrepancies between LC3-II and APP-CTFs were seen between primary (GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff disease) and secondary (Niemann-Pick type C1) lysosomal storage models. APP-CTFs were proportionately higher than LC3-II in cerebellar regions of GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff disease, although LC3-II increased before APP-CTFs in brains of NPC1 mice. Endogenous murine Aβ40 from RIPA-soluble extracts was increased in brains of all three mice. The in vivo relationship between AV and APP-CTF accumulation was also seen in cultured neurons treated with agents that impair primary (chloroquine and leupeptin + pepstatin) and secondary (U18666A and vinblastine) lysosomal flux. However, Aβ secretion was unaffected by agents that induced autophagy (rapamycin) or impaired AV clearance, and LC3-II-positive AVs predominantly co-localized with degradative LAMP-1-positive lysosomes. These data suggest that neuronal macroautophagy does not directly regulate APP metabolism but highlights the important anti-amyloidogenic role of lysosomal proteolysis in post-secretase APP-CTF catabolism.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Amyloid, Autophagy, Endocytosis, Lysosomal Storage Disease, Lysosomes, Neurobiology, Neuron, Secretases, Storage Diseases

Introduction

Neurodegenerative proteinopathies such as Alzheimer disease (AD),4 Parkinson disease, and Huntington disease are defined by progressive accumulation of protein aggregates. In AD, aggregation of the amyloid-β (Aβ) protein and Tau is believed to play a central role in AD pathogenesis (1, 2). A role for endosomal-autophagic-lysosomal (EAL) dysfunction in AD is supported by the presence of enlarged endosomes and increased amounts of lysosomal proteases in AD and Down syndrome brain (3, 4). Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a constitutively active branch of the wider EAL system, involved in the sequestration of cytosolic regions into characteristic double-membrane or multimembrane autophagosomes that are delivered to lysosomes for degradation (5, 6). The term “autophagic vacuole” (AV) is used to describe a spectrum of autophagic structures that include nascent autophagosomes and post-fusion autophagic organelles such as amphisomes (autophagosomes fused with endosomes) and autolysosomes (autophagosomes fused with lysosomes). AVs are identifiable by the protein, LC3-II (phospho-lipidated form of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3-I, MAP1 LC3-I), which is associated with both luminal and cytosolic surfaces of AV membranes (7). Classical autophagy activation is regulated through PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways, although alternative mTOR-independent pathways also exist (5, 8). In neurons, lysosomal processing is highly efficient, and under basal conditions the amounts of AVs are low (9–11). However, in the AD brain, AVs accumulate in degenerating neurons and resemble those seen when AV processing is impaired (9, 12).

Several rare hereditary lysosomal storage diseases also exhibit autophagic dysfunction with pathological changes reminiscent of features seen in AD, such as dystrophic axons, ectopic dendrites, neurofibrillary tangles, and amyloid aggregation (13–16). Glycosphingolipidoses are a subset of lysosomal storage diseases characterized by an accumulation of glycosphingolipids (GSLs), a class of lipids containing at least one monosaccharide linked to a ceramide backbone. GSLs are particularly prevalent in neurons and are required for effective lipid raft functioning (17, 18). Altered neurodevelopment and progressive neurodegeneration are common among GSL storage diseases (19, 20). GM1 gangliosidosis and the GM2 gangliosidosis, Sandhoff disease, are primary GSL storage diseases caused by an absence of active lysosomal enzymes, acid β-galactosidase and β-hexosaminidase (21, 22), respectively. Niemann-Pick type C1 (NPC1) disease is a secondary lysosomal storage disease, caused by defects in the transmembrane NPC1 protein of late endosomes/lysosomes. Its function remains controversial (23), but mutations cause impaired fusion of late endosomes with lysosomes, leading to the storage of multiple lipids, including GSLs (24–26). Mouse models of lysosomal storage disorders recapitulate many facets of the human diseases and provide useful in vivo models for studying EAL dysfunction.

In this study, we investigated the effects of perturbing two separate components of lysosomal flux (27), namely substrate degradation within lysosomes (primary lysosomal flux) and substrate delivery to lysosomes (secondary lysosomal flux) on autophagy and APP metabolism. This was done using mouse models of NPC1, GM1 gangliosidosis, and Sandhoff diseases. mTOR-independent AV accumulation and increased APP-C-terminal fragments (APP-CTFs) were detected in all three mouse models. However, APP-CTF increases were disproportionately higher than AV accumulation in primary storage (GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff) brains, whereas AV accumulation preceded APP-CTF accumulation in secondary storage (NPC1) brains. Total Aβ40 was increased in both NPC1 and GM1 gangliosidosis brains but not Sandhoff brains; however, lipid-associated Aβ40 was increased in all three mouse brains. In cultured neurons, impairments of both primary and secondary lysosomal flux produced similar patterns of AV and APP-CTFs as those seen in mouse models of GSL storage diseases. Interestingly, neither autophagy activation nor impairment of autophagic flux affected the secretion of endogenous murine Aβ. Also, rapamycin-induced generation of nascent autophagosomes did not alter levels of APP or APP-CTFs, suggesting that APP is not directly metabolized in the autophagic pathway. Consistent with the idea that neuronal autophagy is highly efficient, LC3-II-positive AVs predominantly localized to lysosomes and not early or late endosomes. Although these findings indicate that macroautophagy does not play a direct role in the metabolism of APP, it highlights the requirement of efficient lysosomal function in preventing the accumulation of AVs and amyloidogenic APP metabolites.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Primary Antibodies

Unless otherwise stated, all chemical reagents were supplied by Sigma. Primary antibodies were supplied by the following sources: APP/APP-CTF antibody (C1/6.1, anti-mouse, a generous gift from Dr. Paul Mathews, Nathan Kline Institute, New York); LC3 (2G6, anti-mouse, nanotools GmbH, Germany); LC3 (anti-rabbit, Cell Signaling); EEA1 (anti-rabbit, Cell Signaling); CI-MPR (anti-rabbit, Abcam, UK); LAMP-1 (anti-mouse, Abcam, UK); phospho-p70S6 kinase specific for Thr-389 (anti-mouse, Cell Signaling); total p70S6 kinase (anti-rabbit, Cell Signaling); and NPC1 (anti-rabbit, Novus Biologicals, CO).

Mouse Models of GSL Storage Diseases

Three mouse models of GSL storage diseases that recapitulate many of the neuropathological features of the human diseases were used in this study. Niemann-Pick type C1 mice (hereafter referred to as NPC1 mice) were from an established colony of npc1NIH spontaneous mutant mice on a BALB/cJ background that do not translate mRNA for NPC1 into protein (28). GM1 gangliosidosis mice (hereafter referred to as GM1 mice) were from an established colony of β-galactosidase (−/−) mice on a C57BL/6J background (29) generously provided by Dr. Sandra d'Azzo (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). Sandhoff disease mice were from an established colony of β-hexosaminidase (−/−) mice also on a C57BL/6J background (30) and were generously provided by Dr. Rick Proia (National Institutes of Health). Genotypes for each mouse strain were confirmed by PCR as described previously (28–30). Genotypes for NPC1 mice were also confirmed by Western blot. Humane end points were applied in agreement with the United Kingdom Home Office (9–12 weeks for NPC1 mice, 7–9 months for GM1 mice, and 14–16 weeks for Sandhoff mice). Animals were housed in a 12 h light/dark cycle, with food and water provided ad libitum. All animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation using protocols approved by the United Kingdom Home Office (Animal Scientific Procedures Act, 1986). Brains were rapidly removed, and cortical, hippocampal, and cerebellar regions were isolated, flash-frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C pending biochemical analysis. Age-matched wild type littermates were used as controls for each mouse strain.

Preparation of Regional Brain Extracts for Immunoblot Analysis

Frozen brain regions were weighed frozen and homogenized in 10 volumes of RIPA buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% IGEPAL-CA630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitors (5 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin, 120 μg/ml Pefabloc, 2 mm 1,10-phenanthroline), using 10 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer connected to an overhead stirrer (Wheaton, NJ) set to speed 4. The resulting suspension was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. Total protein content of samples was estimated using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce) and equalized to 1 mg/ml using RIPA buffer. Samples were frozen as 1 ml aliquots at −80 °C or boiled for 3 min at 100 °C in 4× Tris-Tricine sample buffer (1× concentration: 750 mm Tris base, pH 8.45, 10% glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.01% phenol red) and subsequently used for Western immunoblot. Optimal LC3-II measurement was achieved using freshly homogenized tissue that was consecutively processed for Western immunoblotting without freezing; therefore, all tissue was analyzed for LC3-II before other proteins.

Culturing, Treatment, and Harvesting of Primary Cortical Neurons

Rat primary cortical neurons were prepared as described previously (9). Briefly, brain cells were isolated from the neocortex of embryonic day 18 (E18) Wistar rat embryos and plated at a density of 100,000 cells/cm2 in 6-well dishes pre-coated with poly-d-lysine (50 μg/ml; Sigma) and incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, 95% atmosphere at 37 °C. One-half of the plating medium was replaced with fresh penicillin/streptomycin-free medium every 3 days until cultures reached 14 days in vitro (DIV14). Neurons were treated at DIV14 with U18666A (2 μg/ml), vinblastine (10 μm), chloroquine (10 μm), leupeptin (20 μm), pepstatin (20 μm), or rapamycin (0.1 μm). Treatments were synchronized so that cultures could be harvested at the same time, i.e. the 48 h interval was initiated first and 1 h interval last. Culture media were removed, and cells were washed once in ambient phosphate-buffered saline solution (1 ml/well) and then lysed and scraped into ice-cold RIPA buffer. Thereafter, neuronal lysates were processed in the same manner as outlined for brain tissue extracts.

Preparation of Mouse Brain Extracts and Conditioned Media from Primary Neurons for Aβ ELISA

Brain extracts were prepared for Aβ ELISA in accordance with protocols described previously (31–33), with some modifications. Whole mouse brain without the brainstem was Dounce-homogenized (10 strokes) at 40% w/v (wet weight) in Tissue Homogenization Buffer (THB, 250 mm sucrose, 20 mm Tris base) containing protease inhibitors (5 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin, 120 μg/ml Pefabloc, 2 mm 1,10-phenanthroline). Homogenates were then diluted 1:1 in diethylamine (DEA) buffer (0.4% diethylamine, 100 mm NaCl) and re-homogenized (6 strokes), and 1 ml aliquots were centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4 °C for 1 h. DEA-containing supernatants were removed and neutralized by addition of 1/10th volume of Tris base (0.5 m, pH 6.8) to 1 volume of DEA supernatant and stored at −80 °C pending analysis. Pellets were solubilized by probe sonication (23 kHz, 10 μm amplitude, 5 s) using a Soniprep 150 (MSE Instruments, Sussex, UK) in RIPA buffer (40% w/v of initial wet weight) with protease inhibitors and centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant, referred to as the RIPA extract, was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until needed.

In primary cortical neurons, the effect of pharmacological agents on Aβ production and secretion was assessed by fully replacing existing culture media with fresh media (1.5 ml/well of a 6-well dish) containing the appropriate drug and incubated for 24 h. Thereafter, the entire conditioned media from each 6-well dish was collected in 15-ml tubes and centrifuged at 200 × g at 4 °C for 10 min to remove cellular debris. Conditioned media were then concentrated ∼9-fold to 1 ml using YM-3 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore, MA).

Murine Aβ Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Aβ from mouse brain extracts and conditioned media was measured using ELISA methods described previously (33, 34), with some modifications. Stock solutions of 1 mg/ml murine Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) peptides (American Peptide Company, Inc., Sunnydale, CA) were made up in 0.1% NH4OH. Thereafter, working stock solutions of 5 pmol/ml were prepared by diluting stock solutions of Aβ in ELISA Capture (EC) Buffer (20 mm sodium phosphate, 2 mm EDTA, 400 mm NaCl, 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.05% CHAPS, 0.4% Block Ace (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan), 0.05% NaN3, pH 7.0) and stored at −80 °C. Capture antibodies (C-terminal specific antibodies for Aβ40 and Aβ42, JRF/cAβ40/10 and JRF/cAb42/26, from Centocor Inc., Radnor, PA) were used at 2.5 μg/ml, and an HRP-conjugated detection antibody (JRF/rAb/2, Centocor Inc.) that recognizes amino acids 1–17 of Aβ was used at a dilution of 1:2500. 100 μl/well of tetramethylbenzidine two-component microwell peroxidase substrate kit (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) was used to develop ELISAs, and colorimetric development was stopped by adding 100 μl/well of o-phosphoric acid (5.7%). Absorbance for plates were read at 450 nm using a Spectra Max M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Immunocytochemistry

Neurons treated as described above were washed (three times) in PBS at room temperature, fixed in ice-cold methanol (−20 °C) for 5 min, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in Blocking Buffer (1% BSA, 2% normal goat serum (Dako, CA), 0.05% NaN3). Neurons were incubated with primary antibodies (5 μg/ml in Blocking Buffer) either overnight (LC3) or for 2 h (EEA1, NPC1, CI-MPR, and LAMP-1) at room temperature. Cells were washed (three times) in PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:1000 in Blocking Buffer, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse, and Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit, Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. To visualize nuclei, cells were washed (three times) in PBS and stained with Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen, 1:10,000 in PBS) for 3 min. Coverslips were mounted onto microscope slides with antifade Gelmount (Biomeda, CA) and cells visualized using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Lactate Dehydrogenase Sequestration Assay

The autophagic sequestration of lactate dehydrogenase in primary cortical neurons was determined using a method previously described by Kopitz et al. (35), with minor modifications. Neurons were harvested in ice-cold Sucrose Buffer (PBS, 10% sucrose, 0.1% BSA, 0.01% Tween 20, 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin, 120 μg/ml Pefabloc, 2 mm 1,10-phenanthroline, pH 7.4). The volume of Sucrose Buffer used was 0.25 ml per well of a 6-well dish. Three wells were pooled for each experimental point, and cell suspensions were probe-sonicated (23 kHz, 5 μm amplitude, 5 s) using a Soniprep 150 (MSE Instruments, Sussex, UK). This suspension was then layered onto 3 ml of an 8% (w/v) Histodenz/Sucrose Buffer and centrifuged at 7,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation, the top 1 ml of each sample was collected and designated as the cytosolic LDH fraction. The resulting pellets were washed twice by resuspending and centrifuging (10,000 × g for 5 min) in Sucrose Buffer. Pellets were then resuspended in Sucrose Buffer containing 0.5 μg/ml digitonin, using a hand held biovortexer (BioSpec Products, OK), and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C to permeabilize AVs and release sequestered LDH. Samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min, and the supernatant was referred to as the sequestered LDH fraction. LDH activity was determined using a formazan-producing assay kit from Innoprot (Derio, Spain).

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblot Analyses

Proteins from brain tissue and primary neuron lysates were analyzed using Tris-glycine and Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE systems. 7% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels were used for NPC1 protein, full-length APP (Fl-APP), phospho- and total p70S6 kinase. 14% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels were used for LC3-II detection, and 16% polyacrylamide Tris-Tricine gels were used for the detection of APP-CTFs. Tris-glycine gel solutions were made from a 30% T (total w/v %), 2.6% C (cross-linker w/v %) acrylamide/bisacrylamide stock solution (National Diagnostics, GA) and run on a triple-wide gel system (C.B.S. Scientific, CA) that allowed for running 31 samples at a time, which made inter-regional comparisons between wild type and NPC1 mice possible. Tris-Tricine gels were made from a 49.5% T, 5% C stock (separating gel) and a 49.5% T, 3.3% C (stacking gel) and run on a vertical electrophoresis unit (width × height, 16.5 × 14.5 cm; Sigma). Samples containing 50 μg of protein were loaded onto gels and run at 150 V. Proteins were transferred onto Optitran reinforced nitrocellulose membrane (0.2 μm pore size; Schleicher & Schuell) at 400 mA for 2 h at 4 °C. Uniform transfer of proteins onto nitrocellulose was confirmed by reversible staining with Ponceau S (0.1% w/v, 1% acetic acid, Sigma). Membranes were then blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% skimmed milk/TBS-T (Tris-buffered saline solution containing 0.1% Tween 20), then washed (three times for 5 min) in TBS-T, and incubated with appropriate primary antibodies in a 1% BSA/TBS-T solution for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed (three times for 5 min) in TBS-T before horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (sheep anti-mouse HRP (Amersham Biosciences) and donkey anti-rabbit (Amersham Biosciences) made in 2.5% milk/TBS-T) were added for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed (three times for 20 min) in TBS-T, and the proteins of interest were visualized using chemiluminescent substrates (Pierce). Fuji Super RX film (FujiFilm, Dusseldorf, Germany) band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.43q) from the National Institutes of Health.

Data Analysis

Statistical significance for percentage comparisons was determined using a Wilcoxon-signed rank test with a theoretical mean of 100%. An unpaired Student's t test was used for experiments where quantitative values were obtained. Prism software (version 4.0c) was used for all statistical analyses, where a p value < 0.05 was deemed significant. Statistical significance is annotated in figures accordingly: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

RESULTS

Autophagic Vacuole Accumulation Is a Common Feature of GSL Storage Diseases

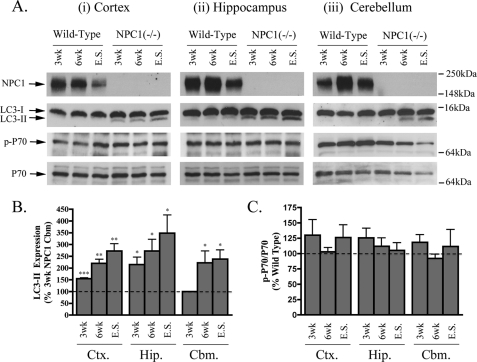

The progressive neurodegeneration that occurs in NPC1 affects specific brain regions differentially. The cerebellum is known to undergo the earliest and most severe degeneration, but cortical and hippocampal regions are also affected (36, 37). To confirm that dysfunctional autophagy is present in brains of mice lacking NPC1 protein (38–40), we measured levels of LC3-II, a marker of both nascent and undegraded AVs. This approach aimed to determine when and in which brain regions the dysfunctional autophagy develops in the NPC1 mouse. As expected (41), basal levels of LC3-II were consistently low in all regions of wild type mouse brain (Fig. 1A). In contrast, a sustained increase in LC3-II was evident in the cortex and hippocampus of NPC1 mice at 3 weeks and in the cerebellum at 6 weeks. LC3-II amounts were highest at end stage in the cortex (273 ± 30%), hippocampus (349 ± 77%), and cerebellum (239 ± 39%), indicating progressive AV accumulation (Fig. 1, A and B). These results highlight the early involvement and widespread nature of dysfunctional autophagy in the NPC1 brain.

FIGURE 1.

Progressive LC3-II accumulation in NPC1 mouse brains. A, representative immunoblots of NPC1, LC3-I/II, p-p70, and total p70 expression in cortical (Ctx, panel i), hippocampal (Hip., panel ii), and cerebellar (Cbm., panel iii) regions of wild type and NPC1 brains at 3 and 6 weeks and end stage (9–12 weeks). B, histogram of LC3-II expression in NPC1 brain regions relative to 3-week NPC1 cerebellar levels (n = 5, mean ± S.E.). Note: comparisons with corresponding wild type mice was not possible due to undetectable basal levels of LC3-II in healthy mice. Considering 3-week NPC1 regions had the lowest expression of LC3-II among the NPC1 mice, their levels were used as a base line for comparing LC3-II changes in other NPC1 brain regions. C, histogram of phospho-p70/total p70 expression in NPC1 brain relative to corresponding brain regions in age-matched wild type controls (n = 6, mean ± S.E.).

AVs can accumulate in neurons due to increased autophagosome production or impaired processing by lysosomes (9). To determine whether AV accumulation in the NPC1 mouse brain is caused by an mTOR-mediated induction of autophagy, mTOR activity was assessed by measuring the extent of mTOR-specific phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase (Fig. 1, A and C). We found no change in the ratio of phospho-/total p70S6 kinase in any of the regions or time points studied. At end stage, the total level of p70S6 kinase in all NPC1 brain regions was decreased relative to age-matched wild type control mice, but the phospho-p70/total p70 ratio was unaffected. These results indicate that the increased expression of LC3-II seen in the NPC1 mouse brain does not require an mTOR-mediated induction of autophagy but may arise from an impaired clearance of constitutively produced autophagosomes by lysosomes (autophagic flux).

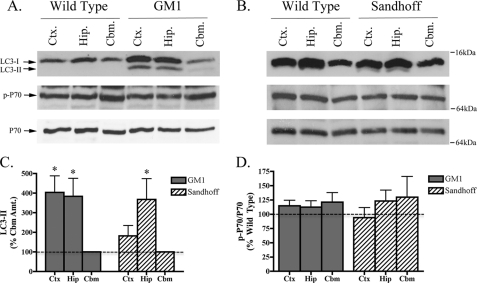

The classification of GSL storage disorders depends on whether gene defects affect GSL metabolism directly (primary storage disease) or indirectly (secondary storage disease). Considering the nonenzymatic nature of NPC1 protein, which facilitates fusion between late endosomes and lysosomes, NPC1 is classed as a secondary GSL storage disease. On the other hand, GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff disease are considered primary GSL storage diseases because they are caused by an absence of functional lysosomal enzymes, acid β-galactosidase and β-hexosaminidase, respectively (21, 22). Thus, having characterized the development of autophagic dysfunction in a mouse model of secondary GSL storage, we were interested to know if impaired autophagic flux also occurred in mouse models of primary GSL storage diseases. Again, this was assessed by measuring both LC3-II expression and mTOR activity. Similar to the situation in NPC1 mouse brain, LC3-II expression was increased in an mTOR-independent manner in brains from both GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff brains (Fig. 2, A–D). However, unlike NPC1 mice, which had similarly high levels of LC3-II expression in the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, LC3-II expression in both GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff mice was higher in the cortex and hippocampus than the cerebellum. As with NPC1 mice, the ratio of phospho-/total p70S6 kinase was unaltered in both GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff brains (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the evident autophagic dysfunction was not mediated by mTOR. Inter-regional LC3-II differences in NPC1, GM1, and Sandhoff mice highlights the fact that although autophagic dysfunction is present in these mouse models, certain brain regions are affected differentially depending on whether the mutant mice have a primary or secondary GSL storage defect. It is also of note that inter-regional differences in LC3-I expression was a general feature seen in the mouse brain, with higher expression found in the hippocampus and cortex compared with cerebellum. This may be due to the proportional expression of LC3-I in cell types of these regions.

FIGURE 2.

LC3-II is increased in GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff disease mouse brains. Representative immunoblots of LC3-I/II, p-p70, and total p70 expression in the cortex (Ctx.), hippocampus (Hip.), and cerebellum (Cbm.) of GM1 gangliosidosis (A) and Sandhoff disease (B) mouse model brains at end stage. C, histogram depicting LC3-II expression as a percentage of cerebellar LC3-II levels in GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff mouse brain regions. D, histogram of phospho-p70/total p70 expression in GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff brains relative to age-matched wild type controls (n = 5 for GM1 mice, n = 5 for Sandhoff mice, mean ± S.E.).

Although the underlying cause of dysfunctional autophagy in mouse models of NPC1, GM1, and Sandhoff disease is likely to stem from impaired processing of constitutively produced AVs (autophagic flux), it is possible that different types of AVs accumulate in each disease depending on direct (autophagosome-lysosome) or indirect (autophagosome-endosome-lysosome) routes affected in each. We therefore sought to utilize these differences to determine whether autophagy plays a direct or indirect role in the metabolism of APP.

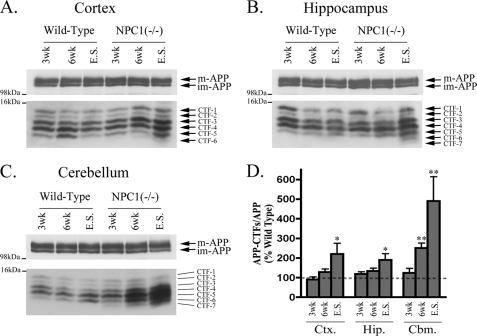

APP-CTFs Levels Do Not Always Correlate with LC3-II in Mouse Models of GSL Storage Diseases

Given the believed importance of APP in AD pathogenesis and the identification of autophagic compartments as important sites for APP metabolism (42, 43), we sought to determine whether autophagic dysfunction in mouse models of GSL storage diseases coincided with altered APP metabolism. We therefore measured amounts of APP holoprotein and its C-terminal fragments (APP-CTFs) in brain extracts from age-matched wild type controls and the three GSL storage disease mouse models. Using Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE and a C-terminal-specific antibody (C1/6.1) that recognizes the last 20 amino acids of APP, at least five CTFs were consistently detected in wild type brain (Fig. 3, A–C). The estimated molecular weights of the APP-CTF species detected were as follows: 13.2 kDa (CTF-1); 12.5 kDa (CTF-2); 12 kDa (CTF-3); 11.6 kDa (CTF-4); and 11.1 kDa (CTF-5). Because these species all have a common C terminus, the observed molecular weight differences likely result due to variations in the N terminus and/or phosphorylation state (44–46). For the purpose of this study, we chose to focus on total APP-CTF levels and normalized these relative to Fl-APP. Relative to wild type mice, 6-week-old NPC1 mice had higher levels of APP-CTFs in cortical and hippocampal regions, but in end stage NPC1 brain, the relative amounts of APP-CTFs were dramatically increased in both cortex (220 ± 54%) and hippocampus (190 ± 31%; Fig. 3D). Accumulation of APP-CTFs occurred earlier in the NPC1 cerebellum, being 2-fold higher at 6 weeks (250 ± 25%) and almost 5-fold higher (489 ± 124%) at end stage. Thus APP-CTFs accumulated earlier and to a greater extent in cerebellum than in either the cortex or hippocampus. Interestingly, at least two additional APP-CTFs, CTF-6 (10.3 kDa) and CTF-7 (10 kDa), which were not present in wild type brain, were detected in hippocampal and cerebellar regions of end stage NPC1 mice. Similar APP-CTFs were also detected in rat primary cortical neurons, and their levels were dramatically increased when neurons were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor, DAPT (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 3.

Progressive APP-CTF accumulation in NPC1 mouse brains. Representative immunoblots of full-length APP (immature (im-APP) and mature (m-APP)), and APP-C-terminal fragments (CTFs 1–7) in cortical (Ctx.) (A), hippocampal (Hip.) (B), and cerebellar (Cbm.) C, regions of wild type and NPC1 brains at 3 and 6 weeks (wk) and end stage (E.S.). D, histogram of APP-CTF/Fl-APP expression in NPC1 brain regions as a percentage of corresponding wild type levels (n = 6 for 3- and 6-week samples, n = 12 for end stage samples, mean ± S.E.).

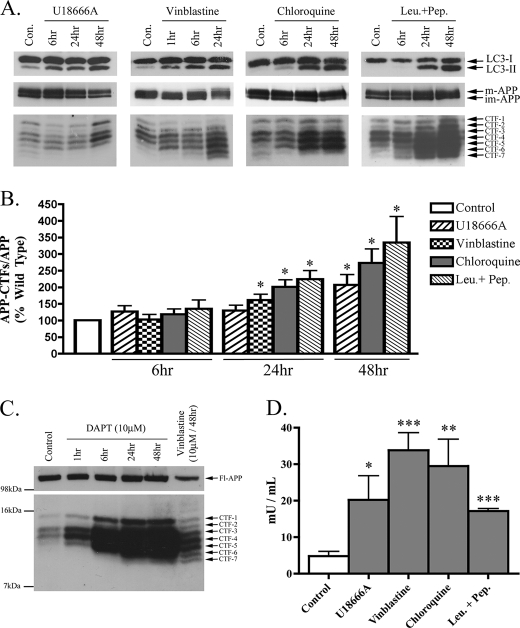

FIGURE 6.

Impaired lysosomal flux causes AV and APP-CTF accumulation in primary cortical neurons. Rat primary cortical neurons (DIV14) were treated with U18666A (2 μg/ml), vinblastine (10 μm), chloroquine (10 μm), and leupeptin + pepstatin (Leu.+Pep.) (each at 20 μm) for the times shown. A, representative immunoblot images of LC3-I/II, APP, and APP-CTF expressions for each treatment condition are shown. B, histogram of APP-CTF/Fl-APP expression in primary neurons treated as in A, n = 6 for all conditions, mean ± S.E.). C, immunoblot confirming the specificity of the APP-CTFs detected in primary cortical neurons using the γ-secretase inhibitor, DAPT (10 μm). Importantly, the CTFs detected in vinblastine (10 μm, 48 h)-treated neurons perfectly co-migrated with those detected in cells treated with DAPT. D, histogram representing amounts of sequestered LDH activity in neurons treated for 24 h, n = 4, mean ± S.E.

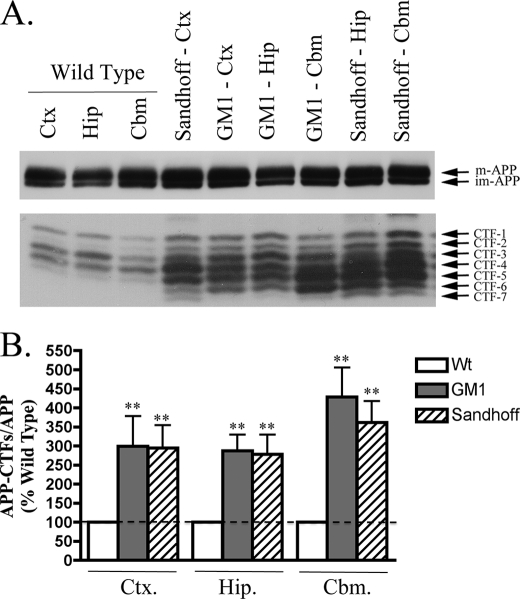

As in NPC1 mouse brain, the levels of Fl-APP in GM1 and Sandhoff disease mice were highly similar to those in wild type brain, whereas the levels of APP-CTFs in cortical, hippocampal, and cerebellar regions were significantly elevated (Fig. 4, A and B, p < 0.01 for GM1 and Sandhoff mice). The extent of APP-CTF accumulation in both GM1 and Sandhoff brain was similar across all three brain regions, with an almost 3-fold increase in the cortex (GM1, 299 ± 79%; Sandhoff, 295 ± 60%) and hippocampus (GM1, 287 ± 42%; Sandhoff, 278 ± 51%), and a 4-fold increase in the cerebellum (GM1, 428 ± 78%; Sandhoff, 361 ± 56%). Considering cerebellar regions of GM1 and Sandhoff mice did not have increased levels of LC3-II (Fig. 2), the observed increase in APP-CTFs may reflect an autophagy-independent mechanism or a mild impairment in autophagy not detectable by monitoring LC3-II.

FIGURE 4.

APP-CTFs accumulate in GM1 and Sandhoff mouse brains. A, representative immunoblot images of full-length APP (immature (im-APP) and mature (m-APP)) and APP-C-terminal fragments (CTFs 1–7) in cortical (Ctx), hippocampal (Hip), and cerebellar (Cbm) regions of wild type and end stage GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff mice. B, histogram of APP-CTF/Fl-APP expression in GM1 and Sandhoff mouse brain regions as a percentage of corresponding wild type levels (n = 8 for GM1 and n = 6 for Sandhoff mice, mean ± S.E.).

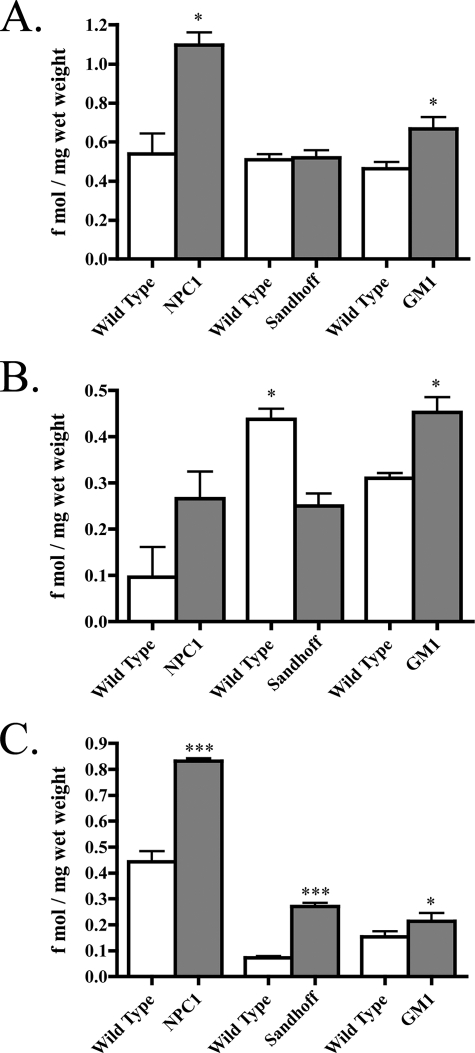

Lipid-associated Aβ Is Increased in Brains of NPC1, Sandhoff, and GM1 Mice

Considering APP-CTF levels were elevated in all three storage mouse brains, and the 99-amino acid-long APP-CFTβ serves as a direct substrate for production of Aβ, we investigated if Aβ was also increased. For this we used an established sequential extraction procedure that allows for the isolation of (a) cytosolic and interstitial Aβ and (b) lipid-associated Aβ (32, 33) First, brains were extracted in a DEA-containing buffer, followed by RIPA buffer extraction. Aβ40 was reliably detected in both the DEA and RIPA extracts; however, Aβ42 was below detectable levels so was not included in the analysis. Total amounts of Aβ40 were determined from the sum of DEA and RIPA soluble extracts and were comparable between wild type mice from each background and age (Fig. 5A). Total Aβ40 was almost 2-fold higher in NPC1 brain (1.1 ± 0.06 fmol/mg wet weight) compared with wild type levels (0.54 ± 0.1 fmol/mg wet weight, p < 0.05; Fig. 5A). Although there was a trend indicating DEA-soluble Aβ40 was raised in NPC1 mice, this was not significant (Fig. 5B); however, Aβ40 from RIPA-soluble extracts was almost 2-fold higher in NPC1 brains (0.83 ± 0.01 compared with 0.44 ± 0.04 fmol/mg, wet weight, p < 0.001, Fig. 5C), suggesting lipid-associated Aβ contributes largely to increased total Aβ40 in NPC1. Although total Aβ40 was not altered in Sandhoff mice (Fig. 5A), RIPA-extractable Aβ40 was increased almost 3-fold (0.073 ± 0.006 fmol/mg wet weight) compared with wild type brain (0.27 ± 0.01 fmol/mg wet weight, p < 0.001; Fig. 5C). Decreased DEA-soluble Aβ40 in Sandhoff mice (Fig. 5B) may explain why total Aβ40 amounts were unchanged. Similar to NPC1 mice, total Aβ40 was significantly raised in brains of GM1 mice (0.67 ± 0.06 fmol/mg wet weight) compared with age-matched wild type mice (0.46 ± 0.03, fmol/mg wet weight, p < 0.05; Fig. 5A). Although RIPA soluble Aβ40 was only marginally increased in GM1 mice (0.21 ± 0.23 fmol/mg wet weight, compared with wild type, 0.15 ± 0.02 fmol/mg wet weight, p < 0.05; Fig. 5C), GM1 mice were the only mice to have significantly higher DEA-soluble Aβ40 (p < 0.05; Fig. 5B). Preliminary studies using a formic acid extraction of post-RIPA pellets did not reveal any indication of insoluble aggregated Aβ in any of the mouse models. Considering the low propensity for murine Aβ to aggregate (47), this was not unexpected. Therefore, it is unlikely that the relative increases in Aβ contribute significantly to the extent of neurodegeneration seen in these mice.

FIGURE 5.

Lipid-associated Aβ accumulates in NPC1, Sandhoff and GM1 mouse brains. Endogenous murine Aβ40 was measured in the brains of NPC1, Sandhoff, and GM1 mice. A, histogram of total Aβ40 measured from the sum of DEA and RIPA extracts in each mouse model (n = 4, mean ± S.E.). B, histogram of DEA soluble Aβ40 measured in each mouse model (n = 4, mean ± S.E.). C, histogram of RIPA soluble Aβ40 measured from each mouse model (n = 4, mean ± S.E.).

Impairments of Primary and Secondary Lysosomal Flux in Cultured Neurons Recapitulate Trends Seen in Brains of GSL Storage Disease Mice

Having characterized temporal and regional changes in LC3-II and APP-CTFs in primary and secondary GSL storage disease mice, we proceeded to investigate the effects of pharmacological agents that impair primary and secondary lysosomal flux in cultured primary neurons. Direct inhibition of primary lysosomal flux was achieved using chloroquine, a lysomotropic agent that neutralizes endosomal-lysosomal pH and their hydrolase activity, and a combination of leupeptin + pepstatin, inhibitors of cysteine- and aspartic acid-cleaving lysosomal hydrolases. Impairment of secondary lysosomal flux was achieved using U18666A, a class II amphiphile that impairs late endosomal delivery to lysosomes by inhibiting NPC1, and vinblastine, an agent that causes depolymerization of microtubules and prevents vesicular transport. As expected, all four drugs caused a time-dependent increase in LC3-II indicative of AV accumulation (Fig. 6, A and B). No change in the ratio of phospho-p70/total p70 was found under any of these treatments, with the exception of vinblastine, which decreased phospho-p70/total p70 at 24 h (data not shown). Overall, the observed AV accumulation under these treatments was mTOR-independent and likely due to an impaired processing of constitutively produced autophagosomes. Neuronal LC3-II amounts rapidly increased upon treatment with U18666A (6 h) and vinblastine (1 h), but chloroquine and leupeptin + pepstatin (24 h) took longer to induce a detectable increase. In addition to all four drugs causing an increase in LC3-II, a concomitant increase in APP-CTF amounts was also observed under these conditions. However, agents that acted directly on lysosomal inhibition (chloroquine, leupeptin + pepstatin) produced higher increases in APP-CTFs than agents that indirectly impaired lysosomal flux (U18666A, vinblastine; Fig. 6B).

In addition to using LC3-II levels as a marker of AV accumulation in primary neurons, we also measured the autophagic sequestration of the long lived cytosolic enzyme LDH (35). Similar to trends seen with LC3-II expression, sequestered LDH was significantly increased by all treatments at the 24-h time point (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, the large amounts of sequestered LDH seen in vinblastine-treated neurons indicate that autophagosome formation is independent of microtubule integrity (48).

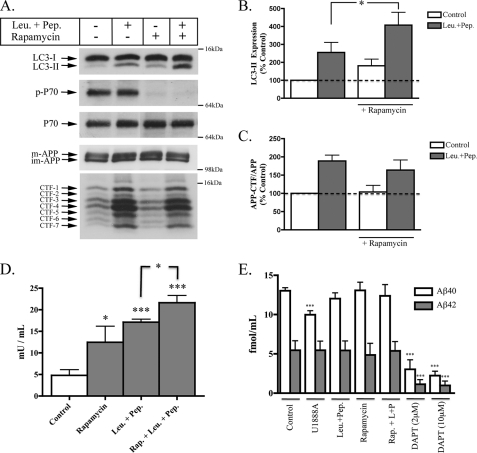

Nascent Autophagosomes Do Not Contribute to APP Metabolism

Considering lysosomes are the terminal destination for cargo delivered by both autophagic and endosomal routes, we applied a method used to measure autophagic flux (49), to determine whether an increased production of nascent autophagosomes directly affects APP metabolism. After 24 h of treatment with rapamycin, LC3-II was significantly increased, but APP-CTF levels were unaffected (Fig. 7, A–C). In agreement with our earlier observation, neurons from the same culture treated with leupeptin + pepstatin had higher levels of LC3-II and APP-CTFs (Fig. 6). Co-treatment with both rapamycin and leupeptin + pepstatin caused a further increase in LC3-II levels but did not significantly increase APP-CTF levels above those of neurons treated with leupeptin + pepstatin alone. Changes in LC3-II expression in autophagic flux experiments were also observed in LDH sequestration studies (Fig. 7D). These data suggest that the extra autophagosomes generated by rapamycin-induced autophagy activation did not significantly alter APP metabolism. Moreover, it seems likely that the accumulation of APP-CTFs seen under conditions of impaired lysosomal flux does not result due to the accumulation of nascent autophagosomes but rather is due to an impaired clearance of endosome-derived APP or APP-CTFs.

FIGURE 7.

Increased formation of nascent autophagosomes does not alter APP metabolism. Rat primary cortical neurons (DIV14) were treated with rapamycin (0.1 μm) in the absence and presence of leupeptin + pepstatin (Leu.+Pep.) (20 μm) for 24 h. A, representative immunoblot images of LC3-I/II, p-p70, p70, APP, and APP-CTF expressions for each treatment condition. B, histogram of LC3-II expression expressed as a percentage of control under each treatment (n = 6, mean ± S.E.). C, histogram of APP-CTF/Fl-APP expression in primary neurons treated with each condition shown in A, n = 6 for all conditions, mean ± S.E. D, histogram representing amounts of sequestered LDH activity in neurons treated for 24 h, n = 4, mean ± S.E. E, histogram depicting the measurements of soluble Aβ from conditioned medium of primary cortical neurons. Treatments used included U18666A (2 μg/ml), leupeptin + pepstatin (Leu.+Pep.) (20 μm), rapamycin (0.1 μm), and the γ-secretase inhibitor, DAPT (2 μm and 10 μm). n = 5 for all conditions, mean ± S.E.

Further evidence that autophagy does not directly contribute to increased amyloidogenic processing of APP comes from experiments where secreted Aβ was measured in conditioned media of the same neurons used to assess effects of LC3-II and APP-CTFs (Fig. 7D). Rapamycin-induced autophagy activation did not alter secretion of murine Aβ40 or Aβ42. However, in two prior studies conflicting effects on Aβ secretion were reported during autophagy activation (42, 50). It is worth noting that the results obtained from our study differ from previous reports in that the levels of Aβ we detected are representative of the endogenously secreted levels from rat neurons that do not overexpress APP. Thus, it would appear that in the absence of APP overexpression, autophagy does not contribute to an increase or decrease in the production of secreted Aβ. Interestingly, treatments that impaired lysosomal flux and caused significant increases in intracellular APP-CTFs did not affect Aβ secretion, with the exception of a minor decrease in Aβ40 secretion seen in U18666A-treated neurons. This suggests that basal production of Aβ from APP and subsequent secretion of monomeric Aβ occurs upstream of the lysosomal catabolism of APP-CTFs. However, evidence that the intracellular accumulation of Aβ can lead to oligomerization (51) allows for the possibility that cellular compartments containing undegraded Aβ or APP-CTFs may act as seeding zones for early amyloid formation. Attempts were made to measure intraneuronal Aβ from cultured neurons; however, amounts produced under all conditions were below the limit of detection of our ELISA (1 fmol/ml). This was expected, considering the amount of available material from neuronal lysates was far less than those used for brain tissue analysis.

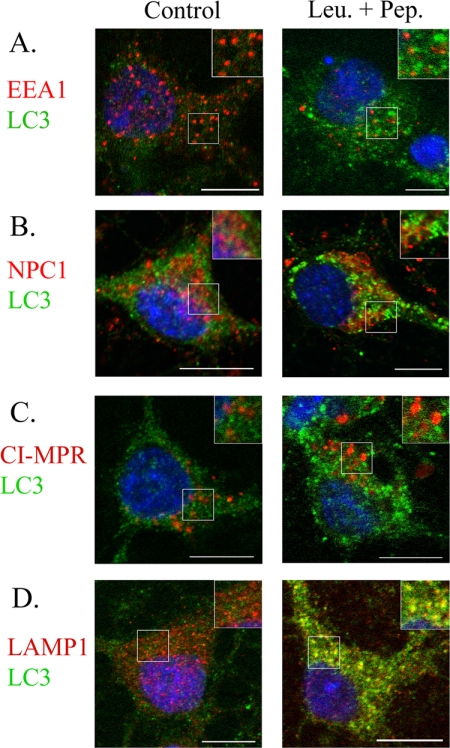

Neuronal AVs Predominantly Fuse with Lysosomes

AVs are known to deliver their cargo to lysosomes either directly through the formation of autolysosomes or indirectly through amphisomes (52, 53). In this study, we considered the likelihood that normal autophagosome trafficking may be altered under conditions where lysosomal AV clearance is impaired. Co-localization between LC3-II and early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), NPC1, the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR), and LAMP1 was performed in leupeptin- and pepstatin-treated neurons to determine the extent of fusion between autophagosomes with early endosomes, late endosomes, and lysosomes under conditions where AV clearance was impaired. There was little or no co-localization between LC3-II and markers of early or late endosomes (Fig. 8, A–C). However, LC3-II and the late endosome/lysosome marker, LAMP1, showed extensive overlap (Fig. 8D). An absence of AV-endosome fusion but predominant AV-lysosome fusion was also seen in with rapamycin-, U18666A-, chloroquine-, and vinblastine-treated neurons (data not shown). Considering these data indicate that neuronal autophagosomes largely fuse with lysosomes, and autophagy activation did not affect APP metabolism, we believe that macroautophagy does not directly regulate the metabolism of APP.

FIGURE 8.

LC3-II positive AVs mainly fuse with lysosomes compared with early or late endosomes. Rat primary cortical neurons (DIV14) were cultured in the absence and presence of leupeptin + pepstatin (Leu.+Pep.) (20 μm) for 24 h to compare LC3-II co-localization with early endosomes, late endosomes, and lysosomes under normal and impaired lysosomal flux conditions. LC3-II-positive AVs (green) rarely co-localized with markers of the early endosomes (EEA1, red, A, inset) and late-endosomes/lysosomes (NPC1, CI-MPR, red, B and C, inset). However, AVs mainly co-localized with LAMP1-positive lysosomes (red, D, inset), indicating autophagosomes predominantly fuse with lysosomes in neurons. Scale bar, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Central to the pathogenesis of AD is the metabolism of APP, which undergoes proteolytic processing and degradation in endosomal-lysosomal compartments (54–56). In light of previous reports that propose a role for autophagy in APP metabolism (42, 43), and evidence that APP metabolism is altered in NPC1 and GM1 brains (14, 57–60), we assessed states of autophagy and APP metabolism in three mouse models of GSL storage diseases to gain a better understanding of the role of autophagy in APP metabolism.

In accordance with previous studies (39, 40, 61), we found substantially higher amounts of the AV membrane marker, LC3-II, in NPC1, GM1 gangliosidosis, and Sandhoff disease mice. In NPC1 mice, LC3-II accumulation was present at 3 weeks, before APP-CTF levels increased. However, substantial increases in both were observed at the end stage of disease. Interestingly, mouse models of GM1 gangliosidosis and Sandhoff disease had disproportionately higher amounts of APP-CTFs than LC3-II in the cerebellum, highlighting an obvious disparity between AV amounts and APP metabolism in this region. Considering AV accumulation in all three mouse models was mTOR-independent, and APP-CTFs accompanied AV increases, we propose that AV accumulation in these diseases is likely to stem from impaired autophagic flux (38) and not from autophagy activation (40).

Although lipid-associated Aβ40 was increased in brains of NPC1, Sandhoff, and GM1 gangliosidosis mice, the amounts were very low and unlikely to contribute to the extensive neurodegeneration seen in these mice. The propensity for human Aβ to aggregate may lead to larger Aβ increases in human forms of these diseases. However, the main emphasis of this study is more concerned with understanding how alterations in normal EAL function impacts on intracellular mechanisms that regulate APP metabolism.

Although the in vivo data demonstrate different relationships between autophagy and APP metabolism in primary and secondary GSL storage diseases, specific manipulations of the EAL system in cultured neurons made it possible to delineate the involvement of primary and secondary lysosomal flux. Similar to results obtained from brain tissue of NPC1 mice, neurons treated with agents that affected secondary lysosomal flux (U18666A and vinblastine) effectively uncoupled AV and APP-CTF accumulation, with AV accumulation preceding APP-CTF accumulation. Alternatively, inhibition of primary lysosomal flux caused by chloroquine, leupeptin + pepstatin caused APP-CTF increases before AV accumulation. Thus in vivo and in vitro data confirm that lysosomes are required for the processing of AVs and APP-CTFs but that APP-CTF accumulation occurs prior to AV accumulation when primary lysosomal flux is impaired. In contrast, AV accumulation induced by secondary lysosomal flux impairment is more sensitive than APP-CTF processing.

The lack of involvement of autophagy in APP metabolism was most apparent in rapamycin-treated neurons, which had increased amounts of LC3-II but did not show any alteration in full-length APP, APP-CTFs, or Aβ secretion. Also, the absence of changes in full-length APP or Aβ secretion, under conditions where primary and secondary lysosomal flux was impaired, suggests that that lysosomes are mainly involved in the catabolism of post-secretase APP-CTFs and are not involved in the constitutive regulation of Aβ secretion. However, this does not exclude an important role for lysosomes in AD pathogenesis, as the amount of APP-CTFs that accumulated in neurons when lysosomal flux was impaired suggests lysosomes play a major role in the catabolic disposal of APP-CTFs that are not degraded by canonical secretase-mediated cleavage. Of particular note in this study was the characterization of five common APP-CTF bands (13.2–11.1 kDa) detected in all brain samples and in primary neurons. The observed molecular weights, immunoreactivity, and increase in the species following inhibition of γ-secretase indicate that they are true γ-secretase substrates. Two additional γ-secretase APP-CTFs (CTF-6, 10.3 kDa; CTF-7, 10 kDa) were also detected in brains of GSL storage disease mice and in primary neurons treated with agents that impair lysosomal flux. The appearance of these two additional APP-CTFs suggests an ineffective attempt by lysosomes to clear the accumulated longer APP-CTFs or that these fragments are produced by noncanonical processing of APP. Interestingly, the biggest proportional increase in CTF-6 and -7 was seen in neurons treated with leupeptin + pepstatin. This indicates that either cysteine or aspartyl hydrolases are responsible for the normal turnover of CTF-6 and -7 or that inhibition of these hydrolases leads to an increase in their production through an alternative pathway. Considering β-CTFs can exert both direct and indirect neurotoxicity through the formation of Aβ (62–65), the alternative cleavage of β-CTFs into lower molecular weight APP-CTFs that lack the Aβ domain may represent an innate defense mechanism that could be utilized for therapeutic benefit.

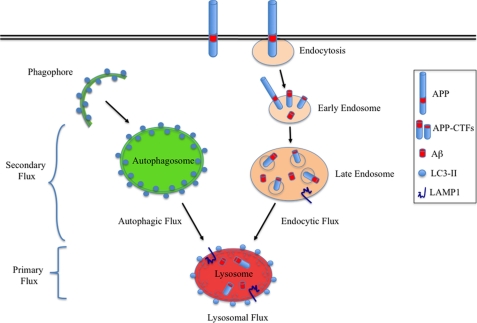

Considering the many roles lipids serve in neurons, there is a growing interest in understanding their involvement in the aging brain and disease. From the regulation of APP processing under different lipid environments (66, 67), to the binding and aggregation of Aβ to different lipids (68–70), AD research has moved beyond proteomics when considering the underlying pathogenesis of this disease. Lipids play an important role as both regulators and cargo of the EAL system, with cholesterol being a classic example of a lipid whose correct trafficking, esterification, and integration within membranes serve vital roles in cell function (18, 71). In this study, all three mouse models of GSL storage had significant alterations in their ability to process AVs and APP-CTFs. Whether these dysfunctions are caused by the nature of primary and secondary lysosomal storage itself or whether specific lipids contribute significantly to autophagic and APP pathology remains to be examined. However, the disparities observed between levels of LC3-II and APP-CTFs, lack of alteration in Aβ secretion caused by modulation of autophagy, and the predominant co-localization of LC3-II with lysosomes indicate that autophagy largely bypasses endosomal compartments in neurons on their way to the lysosome, thus making it unlikely that autophagy is directly involved in the metabolism of APP (Fig. 9). This study emphasizes the anti-amyloidogenic role of lysosomal catabolism and suggests that improving the lysosomal clearance of accumulated AVs and APP metabolites may offer therapeutic benefit to patients with AD.

FIGURE 9.

The Catabolism of APP-CTFs is independent of macroautophagy but dependent on lysosomal flux. Following its partial proteolysis at or close to the plasma membrane, a significant amount of APP-CTFs are delivered to lysosomes for degradation. Under conditions of efficient lysosomal flux, the generation of nascent autophagosomes did not directly alter the expression of full-length APP, APP-CTFs, or the secretion of Aβ, thus indicating that autophagy does not directly influence APP metabolism. However, APP-CTFs and Aβ accumulated under conditions where either primary (Sandhoff and GM1 gangliosidosis) or secondary (NPC1) lysosomal flux was impaired. Considering autophagic and endocytic cargo converge at the lysosome, efficient lysosomal flux is essential for degrading cargo from both routes. Note: the lysosome depicted here represents an active lysosome receiving cargo from autophagic and endocytic routes. LC3-II is present on autolysosomal but not lysosomal membranes.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the generous donation of the APP antibody (C1/6.1) by Dr. Paul Mathews from the Nathan Kline Institute, New York. We also thank Dr. Ian Williams (Oxford, United Kingdom) and Dr. Carlo Sala Frigerio (University College Dublin) for useful discussions and technical advice.

This work was supported by Health Research Board of Ireland Grant PD/2008/40, University College Dublin Seed Fund, Wellcome Trust Grant 069883/B/02/Z, and Science Foundation Ireland Grant 08/1N.1/B2033.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- AV

- autophagic vacuole

- Aβ

- amyloid-β protein

- EAL

- endosomal-autophagic-lysosomal

- GSL

- glycosphingolipid

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- RIPA

- radioimmunoprecipitation assay

- CTF

- C-terminal fragment

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- LDH

- lactate dehydrogenase

- DIV14

- 14 days in vitro

- DEA

- diethylamine

- Fl-APP

- full-length APP.

REFERENCES

- 1. Irvine G. B., El-Agnaf O. M., Shankar G. M., Walsh D. M. (2008) Mol. Med. 14, 451–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Querfurth H. W., LaFerla F. M. (2010) N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 329–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cataldo A. M., Barnett J. L., Mann D. M., Nixon R. A. (1996) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 55, 704–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cataldo A. M., Peterhoff C. M., Troncoso J. C., Gomez-Isla T., Hyman B. T., Nixon R. A. (2000) Am. J. Pathol. 157, 277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. He C., Klionsky D. J. (2009) Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 67–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eskelinen E. L. (2005) Autophagy 1, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noda T., Fujita N., Yoshimori T. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 984–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sarkar S., Ravikumar B., Floto R. A., Rubinsztein D. C. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boland B., Kumar A., Lee S., Platt F. M., Wegiel J., Yu W. H., Nixon R. A. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 6926–6937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hara T., Nakamura K., Matsui M., Yamamoto A., Nakahara Y., Suzuki-Migishima R., Yokoyama M., Mishima K., Saito I., Okano H., Mizushima N. (2006) Nature 441, 885–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Komatsu M., Waguri S., Chiba T., Murata S., Iwata J., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Tanaka K. (2006) Nature 441, 880–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nixon R. A., Wegiel J., Kumar A., Yu W. H., Peterhoff C., Cataldo A., Cuervo A. M. (2005) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 64, 113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walkley S. U., Suzuki K. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1685, 48–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saito Y., Suzuki K., Nanba E., Yamamoto T., Ohno K., Murayama S. (2002) Ann. Neurol. 52, 351–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohmi K., Kudo L. C., Ryazantsev S., Zhao H. Z., Karsten S. L., Neufeld E. F. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8332–8337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nixon R. A., Yang D. S., Lee J. H. (2008) Autophagy 4, 590–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ariga T., McDonald M. P., Yu R. K. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 49, 1157–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lingwood D., Simons K. (2010) Science 327, 46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Futerman A. H., van Meer G. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 554–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jeyakumar M., Dwek R. A., Butters T. D., Platt F. M. (2005) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 713–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Okada S., O'Brien J. S. (1968) Science 160, 1002–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sandhoff K., Andreae U., Jatzkewitz H. (1968) Pathol. Eur. 3, 278–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lloyd-Evans E., Platt F. M. (2010) Traffic 11, 419–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lloyd-Evans E., Morgan A. J., He X., Smith D. A., Elliot-Smith E., Sillence D. J., Churchill G. C., Schuchman E. H., Galione A., Platt F. M. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neufeld E. B., Wastney M., Patel S., Suresh S., Cooney A. M., Dwyer N. K., Roff C. F., Ohno K., Morris J. A., Carstea E. D., Incardona J. P., Strauss J. F., 3rd, Vanier M. T., Patterson M. C., Brady R. O., Pentchev P. G., Blanchette-Mackie E. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9627–9635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang M., Dwyer N. K., Love D. C., Cooney A., Comly M., Neufeld E., Pentchev P. G., Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Hanover J. A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4466–4471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gordon P. B., Høyvik H., Seglen P. O. (1992) Biochem. J. 283, 361–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Loftus S. K., Morris J. A., Carstea E. D., Gu J. Z., Cummings C., Brown A., Ellison J., Ohno K., Rosenfeld M. A., Tagle D. A., Pentchev P. G., Pavan W. J. (1997) Science 277, 232–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hahn C. N., del Pilar Martin M., Schröder M., Vanier M. T., Hara Y., Suzuki K., Suzuki K., d'Azzo A. (1997) Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sango K., Yamanaka S., Hoffmann A., Okuda Y., Grinberg A., Westphal H., McDonald M. P., Crawley J. N., Sandhoff K., Suzuki K., Proia R. L. (1995) Nat. Genet. 11, 170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schmidt S. D., Jiang Y., Nixon R. A., Mathews P. M. (2005) Methods Mol. Biol. 299, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Savage M. J., Trusko S. P., Howland D. S., Pinsker L. R., Mistretta S., Reaume A. G., Greenberg B. D., Siman R., Scott R. W. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 1743–1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burns M. P., Igbavboa U., Wang L., Wood W. G., Duff K. (2006) Neuromolecular Med. 8, 319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmidt S. D., Nixon R. A., Mathews P. M. (2005) Methods Mol. Biol. 299, 279–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kopitz J., Kisen G. O., Gordon P. B., Bohley P., Seglen P. O. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111, 941–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Taniguchi M., Shinoda Y., Ninomiya H., Vanier M. T., Ohno K. (2001) Brain Dev. 23, 414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ong W. Y., Kumar U., Switzer R. C., Sidhu A., Suresh G., Hu C. Y., Patel S. C. (2001) Exp. Brain Res. 141, 218–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liao G., Yao Y., Liu J., Yu Z., Cheung S., Xie A., Liang X., Bi X. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 171, 962–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ko D. C., Milenkovic L., Beier S. M., Manuel H., Buchanan J., Scott M. P. (2005) PLoS Genet. 1, 81–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pacheco C. D., Kunkel R., Lieberman A. P. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 1495–1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mizushima N., Yamamoto A., Matsui M., Yoshimori T., Ohsumi Y. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1101–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu W. H., Cuervo A. M., Kumar A., Peterhoff C. M., Schmidt S. D., Lee J. H., Mohan P. S., Mercken M., Farmery M. R., Tjernberg L. O., Jiang Y., Duff K., Uchiyama Y., Näslund J., Mathews P. M., Cataldo A. M., Nixon R. A. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171, 87–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pickford F., Masliah E., Britschgi M., Lucin K., Narasimhan R., Jaeger P. A., Small S., Spencer B., Rockenstein E., Levine B., Wyss-Coray T. (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2190–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee M. S., Kao S. C., Lemere C. A., Xia W., Tseng H. C., Zhou Y., Neve R., Ahlijanian M. K., Tsai L. H. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 163, 83–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suzuki T., Nakaya T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29633–29637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kimberly W. T., Zheng J. B., Town T., Flavell R. A., Selkoe D. J. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 5533–5543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bush A. I., Pettingell W. H., Multhaup G., d Paradis M., Vonsattel J. P., Gusella J. F., Beyreuther K., Masters C. L., Tanzi R. E. (1994) Science 265, 1464–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Punnonen E. L., Autio S., Kaija H., Reunanen H. (1993) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 61, 54–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. (2010) Cell 140, 313–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jaeger P. A., Pickford F., Sun C. H., Lucin K. M., Masliah E., Wyss-Coray T. (2010) PLoS One 5, e11102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Walsh D. M., Tseng B. P., Rydel R. E., Podlisny M. B., Selkoe D. J. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 10831–10839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Berg T. O., Fengsrud M., Strømhaug P. E., Berg T., Seglen P. O. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21883–21892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gordon P. B., Seglen P. O. (1988) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 151, 40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cole G. M., Bell L., Truong Q. B., Saitoh T. (1992) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 674, 103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Siman R., Mistretta S., Durkin J. T., Savage M. J., Loh T., Trusko S., Scott R. W. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 16602–16609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Haass C., Koo E. H., Mellon A., Hung A. Y., Selkoe D. J. (1992) Nature 357, 500–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Burns M., Gaynor K., Olm V., Mercken M., LaFrancois J., Wang L., Mathews P. M., Noble W., Matsuoka Y., Duff K. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 5645–5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yamazaki T., Chang T. Y., Haass C., Ihara Y. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4454–4460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jin L. W., Shie F. S., Maezawa I., Vincent I., Bird T. (2004) Am. J. Pathol. 164, 975–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van der Voorn J. P., Kamphorst W., van der Knaap M. S., Powers J. M. (2004) Acta Neuropathol. 107, 539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takamura A., Higaki K., Kajimaki K., Otsuka S., Ninomiya H., Matsuda J., Ohno K., Suzuki Y., Nanba E. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 367, 616–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nalbantoglu J., Tirado-Santiago G., Lahsaïni A., Poirier J., Goncalves O., Verge G., Momoli F., Welner S. A., Massicotte G., Julien J. P., Shapiro M. L. (1997) Nature 387, 500–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kozlowski M. R., Spanoyannis A., Manly S. P., Fidel S. A., Neve R. L. (1992) J. Neurosci. 12, 1679–1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chang K. A., Suh Y. H. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 97, 461–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kim J. H., Anwyl R., Suh Y. H., Djamgoz M. B., Rowan M. J. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 1327–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hartmann T., Kuchenbecker J., Grimm M. O. (2007) J. Neurochem. 103, Suppl. 1, 159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Osenkowski P., Ye W., Wang R., Wolfe M. S., Selkoe D. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22529–22540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ariga T., Kobayashi K., Hasegawa A., Kiso M., Ishida H., Miyatake T. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 388, 225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dante S., Hauss T., Dencher N. A. (2002) Biophys. J. 83, 2610–2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Matsuzaki K., Noguch T., Wakabayashi M., Ikeda K., Okada T., Ohashi Y., Hoshino M., Naiki H. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768, 122–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mukherjee S., Maxfield F. R. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1685, 28–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]