Abstract

Protein aggregation is a hallmark of many neuronal disorders, including the polyglutamine disorder spinocerebellar ataxia 3 and peripheral neuropathies associated with the K141E and K141N mutations in the small heat shock protein HSPB8. In cells, HSPB8 cooperates with BAG3 to stimulate autophagy in an eIF2α-dependent manner and facilitates the clearance of aggregate-prone proteins (Carra, S., Seguin, S. J., Lambert, H., and Landry, J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1437–1444; Carra, S., Brunsting, J. F., Lambert, H., Landry, J., and Kampinga, H. H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5523–5532). Here, we first identified Drosophila melanogaster HSP67Bc (Dm-HSP67Bc) as the closest functional ortholog of human HSPB8 and demonstrated that, like human HSPB8, Dm-HSP67Bc induces autophagy via the eIF2α pathway. In vitro, both Dm-HSP67Bc and human HSPB8 protected against mutated ataxin-3-mediated toxicity and decreased the aggregation of a mutated form of HSPB1 (P182L-HSPB1) associated with peripheral neuropathy. Up-regulation of both Dm-HSP67Bc and human HSPB8 protected and down-regulation of endogenous Dm-HSP67Bc significantly worsened SCA3-mediated eye degeneration in flies. The K141E and K141N mutated forms of human HSPB8 that are associated with peripheral neuropathy were significantly less efficient than wild-type HSPB8 in decreasing the aggregation of both mutated ataxin 3 and P182L-HSPB1. Our current data further support the link between the HSPB8-BAG3 complex, autophagy, and folding diseases and demonstrate that impairment or loss of function of HSPB8 might accelerate the progression and/or severity of folding diseases.

Keywords: Autophagy, Chaperone Chaperonin, Drosophila, Mutant, Polyglutamine Disease, Molecular Chaperones, Mutated HSPB8

Introduction

Aggregation of misfolded mutated proteins and neuronal loss are hallmarks of many neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and polyglutamine disorders (e.g. Huntington disease and spinocerebellar ataxia 3), which are often referred to as protein conformational disorders (1, 2). Moreover, aggregation of mutated proteins is also commonly observed in several types of neuromuscular and muscular disorders (e.g. Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A, desmin-related myopathy, and muscular dystrophy), thus further underscoring a causal role for protein misfolding in neuronal and muscular cell degeneration (3–6). Hence, suppression of protein aggregation and acceleration of protein removal are considered to be common therapeutic approaches to treat the protein conformational disorders (7, 8). Both suppression of protein aggregation and degradation of misfolded proteins can be achieved through stimulation of the protein quality control system, which includes molecular chaperones of the heat shock protein (HSP)3 families and degradation systems (proteasome, chaperone-mediated autophagy, and macroautophagy) (8). It has been shown that up-regulation of molecular chaperones and stimulation of autophagy can protect from the toxic effects of aggregating proteins both in cellular and animal (e.g. Drosophila melanogaster) models of protein conformation disorders (9–12). Conversely, impairment of molecular chaperone function may have detrimental effects for cellular viability, and failure of the HSP system with age is a likely relevant factor to the age of onset of protein misfolding diseases and for the aging process itself (13). Intriguingly, mutations in several members of the human small HSP family, which includes 10 members (sHSP/HSPB; HSPB1–HSPB10) (14), have been associated with neuronal and muscular disorders. They include mutated forms of HSPB4 that are associated with congenital cataract, of HSPB5 causing desmin-related myopathy, and of HSPB1 and HSPB8 that lead to peripheral neuropathies (6, 15–18).

Here, we focus on HSPB8 (also named HSP22/H11/E2IG1), for which two mutations (K141E and K141N) have been associated with autosomal dominant distal hereditary motor neuropathy and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2L (16, 17). Hereditary peripheral neuropathies are characterized by dysfunction in either the axon (axonal neuropathies) or in the myelin sheath of the peripheral motor and/or sensory neurons (demyelinating neuropathies) and by progressive muscle weakness and atrophy (19). Other genes (besides HSPB8) that are mutated in these diseases include Rab7, DNM2, and LITAF/SIMPLE, which are involved in protein sorting and lysosome-mediated degradation, thus suggesting that improper protein degradation may participate in the underlying pathogenesis (20–24). For Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1, which is characterized by the aggregation of mutated peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22), a progressive impairment of the proteasome function was found (25–27). Interestingly, mutated PMP22 is mainly targeted to autophagy for degradation (3, 28). As such, these data point to imbalanced protein homeostasis as a possible general event implicated in the pathogenesis and/or progression of neurodegenerative and neuromuscular disorders.

We recently found that, in cells, HSPB8 modulates autophagy-mediated protein degradation. HSPB8 acts in a complex with BAG3 (11), a member of the BAG family of proteins (29–31), and the complex facilitates the clearance of misfolded aggregate-prone proteins (11, 32, 33). In the current study, we first identified HSP67Bc as a D. melanogaster functional ortholog of human HSPB8, and we show that, like HSPB8, Dm-HSP67Bc interacts with Starvin, the sole BAG D. melanogaster protein (34), and that Dm-HSP67Bc stimulates autophagy. Both human HSPB8 and Dm-HSP67Bc reduce aggregation of ataxin-3 containing an expanded polyglutamine tract and of a mutated form of HSPB1 (P182L-HSPB1) that is associated with peripheral neuropathy. Up-regulation of both Dm-HSP67Bc and human HSPB8 protects against mutated polyglutamine protein-induced eye degeneration in an in vivo Drosophila model of spinocerebellar ataxia 3 (35). Moreover, Dm-HSP67Bc down-regulation increased the SCA3-mediated eye degeneration in vivo. Interestingly, the disease-associated K141E and K141N mutated forms of HSPB8 showed a partial loss of function in cells and/or in vivo, suggesting that loss of HSPB8 activity may contribute to protein aggregation-related diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Reagents

The pAc5.1-V5 vector from Invitrogen was used to generate all of the expression constructs for Drosophila Schneider S2 cells. pAc5.1-GFP vector, encoding for GFP; pAc5.1-GFP-Htt74Q vector, encoding for the GFP-tagged huntingtin exon 1 fragment with 74 CAG repeats; and pAc-GFP-LC3 vector, encoding for GFP-tagged LC3 were generated by PCR using pEGFC1 (Clontech), pGFP-HDQ74 (Dr. D. C. Rubinsztein (36)), and pGFP-LC3 (Dr. T. Yoshimori (37)), respectively, as templates. pAc5.1-V5-mRFP-Htt128Q vector encoding for the V5-mRFP-tagged huntingtin exon 1 fragment with 128 CAG repeats was generated by PCR using specific primers. pAc5.1-V5-HSP67Bc, pAc5.1-V5-L(2)efl, pAc5.1-V5-CG14207, pAc5.1-V5-Starvin, and pAc-Myc-GADD34 vectors, encoding for V5-tagged HSP67Bc, L(2)efl, CG14207, Starvin, and Drosophila GADD34, respectively, were obtained by PCR using the Gold cDNA Library (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN) as template. The sequences encoding for the Drosophila small HSPs and for Starvin were subsequently subcloned into the pCDNA5-FRT-TO-V5 vector for expression in mammalian cells. Vectors encoding for Myc-HSPB8, Myc-K141E, Myc-K141N, Myc-BAG3, and Myc-LC3 were described previously (11, 37). P182L-HSPB1 was created by mutagenesis reaction using the pCDNA-HSPB1, expressing human wild-type HSPB1 as template. Rapamycin, pepstatin A, and E64d were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Drosophila Stocks, Genetics

Fly stocks were raised on standard corn meal-agar media. Fly crosses and experiments were carried out according to standard procedures at 25 °C. The GAL4/UAS system was used to drive targeted gene expression (38). For targeting gene expression in eyes, the gmr-GAL4 fly line (stock number 1104) was used, and for ubiquitous gene expression, the actin 5C-GAL4 fly line (stock number 4414) was used; driver stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (Indiana University). All transgenic fly lines were constructed at Genetic Services Inc. (Sudbury, MA), and the background strain w1118 of Genetic Services was used as a control. The transgenic fly line bearing the gmr-GAL4 SCA3trQ78 transgene, expressing a truncated form of human ataxin 3 with 78 glutamine repeats, was kindly provided by Prof. N. Bonini (35). Wild-type HSPB8 and mutant K141E and K141N HSPB8 cDNAs were subcloned into the pUAST vector and sequence-verified. UAS-HSPB8 wild type, UAS-HSPB8 K141E, and UAS-HSPB8 K141N transgenic flies were generated by germ line transformation of w1118 embryos using standard procedures (Genetic Services Inc.). Independent insertions of the human wild-type and mutated forms of HSPB8 were tested. RNAi lines against Dm-HSP67Bc (CG4190) were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi center (VDRC). Genotypes were as follows: gmr-GAL4 UAS-SCA3trQ78/CyO; UAS-CG4190 RNAi#1/TM3 (VDRC ID: 26416); UAS-CG4190 RNAi#2/TM3 (VDRC ID: 26417); UAS-V5-HSP67Bc/TM3; UAS-HSPB8#1/CyO; UAS-HSPB8#2/CyO; UAS-HSPB8#6/TM3; UAS-HSPB8#8/CyO; UAS-K141E#2/CyO; UAS-K141E#4/CyO; UAS-K141E#8/TM3; UAS-K141E#9/TM3; UAS-K141N#1/CyO; UAS-K141N#3/CyO; UAS-K141N#8/CyO.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK-293T (human embryonal kidney) cells were grown at 37 °C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with high glucose (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were cultured at 25 °C in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Both human and Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation as described previously (39).

Microscopy and Immunohistochemistry

To evaluate the effects of molecular chaperone overexpression or knockdown on eye morphology and degeneration in the gmr-GAL4 SCA3(78)Q flies, light microscopic images of the eyes of 1-day-old adult flies were taken using a stereoscopic microscope model SZ40 (Olympus). For immunocytochemistry, cells were grown on coated coverslips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde phosphate buffer, and processed as described previously (39). Third instar larval muscular tissues were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde phosphate buffer, and stained with specific antibodies. Paraffin-embedded human skeletal muscle sections were subjected to immunostaining with specific antibodies. For statistical analysis, at least three independent samples were analyzed using the t test.

Preparation of Protein Extracts and Antibodies

Cells were scraped and homogenized in 2% SDS lysis buffer, whereas protein samples from fly heads were prepared by homogenizing 20 heads from either 1–2-day-old or 20-day-old flies in 100 μl of 2% SDS lysis buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and then processed for Western blotting. For rhodopsin 1 detection, protein samples were not boiled prior to SDS-PAGE. Anti-HSPB8 and anti-BAG3 are rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human HSPB8 and BAG3, respectively (11). The rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-HSP67Bc was raised against the C-terminal peptide CHKEAGPAASASEPEAK of Drosophila melanogaster HSP67Bc coupled to the keyhole limpet hemocyanin.

Mouse monoclonal anti-α-actinin and mouse monoclonal anti-γ-tubulin were from Sigma-Aldrich, whereas mouse monoclonal anti-Myc (9E10) was from the American Type Culture Collection. Mouse monoclonal anti-total-eIF2α and rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-eIF2α were from Cell Signaling and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively. Mouse monoclonal anti-GFP and mouse monoclonal anti-V5 were from Clontech and Invitrogen, respectively. Mouse monoclonal anti-rhodopsin 1 (4C5) was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank.

Immunoprecipitation Technique

For immunoprecipitation from transfected cells, 24 h post-transfection, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 3% glycerol, 1 mm DTT, complete EDTA-free (Roche Applied Science). The cell lysates were centrifuged and cleared with A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) at 4 °C for 1 h. A/G beads complexed with specific antibodies (anti-V5 or anti-Myc antibodies) were added to the precleared lysates. After incubation for 2 h at 4 °C, the immune complexes were centrifuged. Beads were washed four times with the lysis buffer; both co-immunoprecipitated proteins and input fractions were resolved on SDS-PAGE. For the immunoprecipitation of endogenous HSP67Bc from fly head extracts, 100 fly heads for each genotype (gmr-GAL4/+, used as negative control, and gmr-GAL4/V5-Starvin, overexpressing V5-tagged Starvin) were extracted in 400 μl of lysis buffer. The tissue lysates were processed for immunoprecipitation as mentioned above.

RESULTS

D. melanogaster HSP67Bc Is the Closest Functional Ortholog of Human HSPB8

Whereas the human genome encodes for 10 sHSPs (HSPB1-HSPB10) (14) and for six BAG proteins (BAG1–BAG6) (31), the D. melanogaster genome encodes for 11 small heat shock proteins (small HSPs) (40) and for only one BAG protein, Starvin (34). It has already been shown that knockdown of Starvin results in a severe failure to ingest food and in growth defects, most likely due to impairment of muscle maturation and/or function (34). Interestingly, BAG3 knock-out mice show a fulminant myopathy and premature death, due to the progressive degeneration of skeletal muscles (41). These data strongly suggest that Starvin may share some of the key functions of human BAG3 and may represent the D. melanogaster functional ortholog of human BAG3. Among the D. melanogaster sHSPs, only a few have been characterized in the past (e.g. HSP22, HSP23, HSP26, and HSP27) (42–44), and so far their human functional orthologs have not been elucidated. Dm-HSP22 is a mitochondrial protein (45) and Dm-HSP27 is exclusively nuclear (46, 47); thus, it is very unlikely that they could be the functional orthologs of human HSPB8, which is mainly cytosolic. Unlike human HSPB8, but similarly to human HSPB1 and HSPB5 (48), Dm-HSP23 and Dm-HSP26 have protein refolding activities (42). On the basis of sequence homology, one would predict that, among the remaining seven uncharacterized members of the D. melanogaster small HSP family, L(2)efl is the D. melanogaster homolog of human HSPB8 (supplemental Fig. 1A). However, based on a screen previously performed in our laboratory, an alternative candidate could be HSP67Bc, which, similarly to human HSPB8, prevented the aggregation of mutated polyglutamine proteins4 (also see below) (Figs. 3–5). Finally, it was reported that CG14207 mildly protected against mutated ataxin 3-mediated induced degeneration in a fly model of spinocerebellar ataxia 3 (35); in addition, in a yeast two-hybrid screen, CG14207 was reported to interact with the D. melanogaster BAG protein Starvin (49) and to be located, in fly muscles, at the Z band, a structure that is also enriched in Starvin (50). We thus decided to focus on these three proteins, L(2)efl, HSP67Bc, and CG14207, to identify the closest D. melanogaster functional ortholog of human HSPB8.

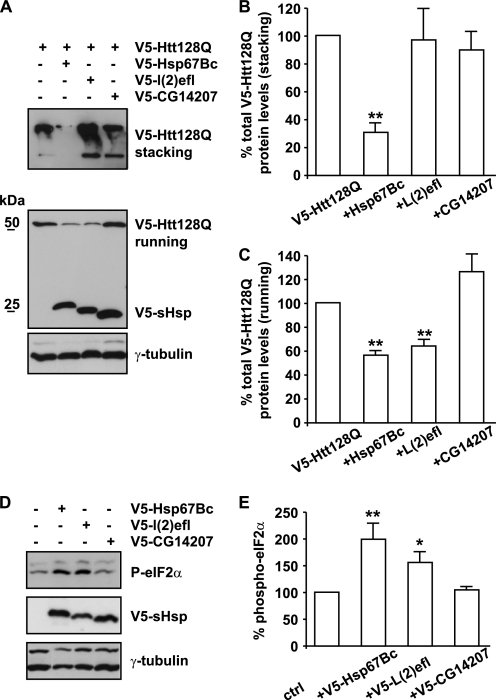

FIGURE 3.

HSP67Bc inhibits the accumulation of both soluble and high molecular weight insoluble mutated huntingtin in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells. A, Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected with vectors encoding for mutated huntingtin with a 128-glutamine repeat (V5-Htt128Q) alone or together with either V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, or V5-CG14207, and total proteins were extracted 48 h post-transfection. Quantification of the effect of the chaperones on the accumulation of the high molecular weight insoluble forms retained in the stacking gel (B) and the soluble monomeric V5-Htt128Q (C) is shown. **, p < 0.001; average values ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 4–6 independent samples. D, HEK-293 cells were transfected with vectors encoding for either mRFP, V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, or V5-CG14207; total proteins were extracted 24 h post-transfection, and levels of phospho-eIF2α were measured by Western blotting. E, quantification of the effect of the chaperones on the levels of phospho-eIF2α. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. of n = 3 independent samples.

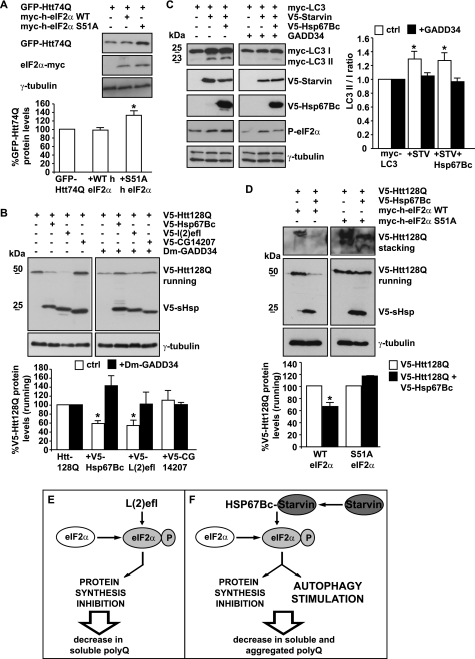

FIGURE 4.

Similarly to human HSPB8, the ability of HSP67Bc to decrease mutated huntingtin accumulation/aggregation and to induce autophagy is eIF2α-dependent. A, impairment of the eIF2α pathway increases mutated polyglutamine protein levels in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected with vectors encoding for GFP-Htt74Q and either Myc-tagged human wild-type eIF2α or Myc-tagged non-phosphorylatable human eIF2α S51A. 48 h post-transfection, the total levels of GFP-Htt74Q were quantified (*, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 3 independent samples). B, HSP67Bc and L(2)efl decrease mutated huntingtin soluble levels via the eIF2α pathway. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected with vectors encoding for V5-Htt128Q alone or together with either V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, or V5-CG14207. Where indicated (+), a vector encoding for D. melanogaster GADD34 (Dm-GADD34) was also co-transfected. Total proteins were extracted 48 h later, and V5-Htt128Q soluble (running) levels were analyzed by Western blotting. *, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. of n = 3 independent samples. C, the induction of LC3 lipidation by HSP67Bc and Starvin is dependent on the phosphorylation of eIF2α. HEK293T cells were transfected with vectors encoding for Myc-LC3 alone or together with V5-Starvin or V5-Starvin and V5-HSP67Bc. Where indicated (+), cells were cotransfected with a vector encoding for the C terminus of GADD34, which inhibits the phosphorylation of endogenous eIF2α. Cell lysates were prepared 44 h post-transfection and analyzed by Western blotting. *, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. of n = 3–4 independent samples. D, S51A eIF2α completely abrogated the ability of HSP67Bc to decrease V5-Htt128Q soluble (running) and insoluble (stacking) levels. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected with vectors for V5-Htt128Q alone or together with V5-HSP67Bc and either human wild-type Myc-eIF2α or the non-phosphorylatable mutant S51A. Total proteins were extracted 48 h later. Quantification of the soluble (running) protein levels of V5-Htt128Q normalized against endogenous γ-tubulin is shown (*, p < 0.01; average values ± S.E. of n = 3 independent samples). E and F, schematic model showing the putative mechanism of action of L(2)efl and HSP67Bc. E, overexpression of L(2)efl leads to the phosphorylation of eIF2α, thereby causing a translational shutdown. This will result in a decrease of the levels of soluble poly(Q) proteins, without affecting significantly the rate of their aggregation. F, overexpression of HSP67Bc, which interacts with Starvin, also leads to the phosphorylation of eIF2α, which, however, causes both translational shutdown and stimulation of autophagy. As a consequence, HSP67Bc-Starvin leads to a decrease of the levels of soluble poly(Q) proteins, but it also facilitates the clearance of aggregated poly(Q) proteins by stimulating autophagy.

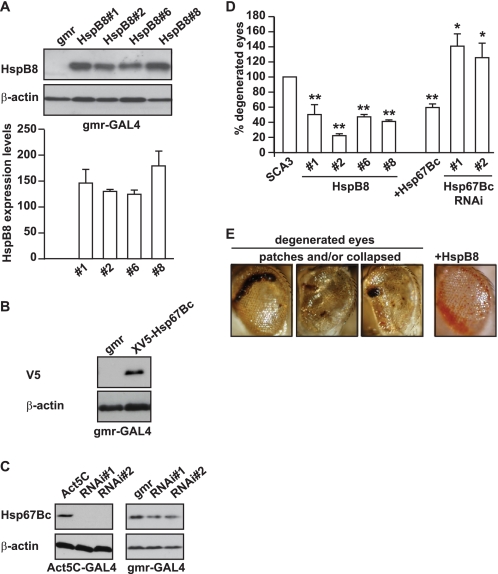

FIGURE 5.

Overexpression of human HSPB8 or Dm-HSP67Bc protects against mutated SCA3-induced eye degeneration in vivo. grm-GAL4-driven expression levels of human HSPB8 (transgenic lines 1, 2, 6, and 8; A) and of V5-HSP67Bc (B). The expression levels of the different transgenic lines expressing human HSPB8 were not significantly different. GMR, gmr-GAL4/+; HSPB8#1, gmr-GAL4/UAS-HSPB8#1, etc.; V5-HSP67Bc, gmr-GAL4/+; UAS-V5-HSP67Bc/+. C, Act5C-GAL4-driven and gmr-GAL4-driven knockdown of Dm-HSP67Bc with two independent UAS RNAi lines (VDRC transformant lines ID 26416 and 26417) grown at 25 °C showing decreased expression of the endogenous protein. Protein levels were measured using protein extracts from 1–2-day-old fly heads. Left, Act5C, Act5C-GAL4/+; RNAi#1, Act5C-GAL4/+; UAS-CG4190 RNAi#1/+; RNAi#2, Act5C-GAL4/+; UAS-CG4190 RNAi#2/+. Right, gmr, gmr-GAL4/+; RNAi#1, gmr-GAL4/+; UAS-CG4190 RNAi#1/+; RNAi#2, gmr-GAL4/+; UAS-CG4190 RNAi#2/+. D, quantification of eye degeneration in flies overexpressing either SCA3(78Q) alone (or in combination with HSPB8 or HSP67Bc). Co-expression of human HSPB8 or V5-HSP67Bc significantly decreases the percentage of flies with degenerated eyes (dark patches and/or collapsed eyes) as compared with control flies, whereas knockdown of endogenous HSP67Bc enhances eye degeneration. SCA3, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/+; HSPB8#1, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/UAS-HSPB8#1, etc.; HSP67Bc, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/+; UAS-V5-HSP67Bc/+; HSP67Bc RNAi#1, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/+; UAS-CG4190 RNAi#1/+; HSP67Bc; RNAi#2, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/+; UAS-CG4190 RNAi#2/+. Total number of eyes scored was 200–400; **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 3 independent experiments. E, representative picture showing SCA3(78Q) flies with degenerated eyes and the partial rescue obtained by overexpression of human HSPB8.

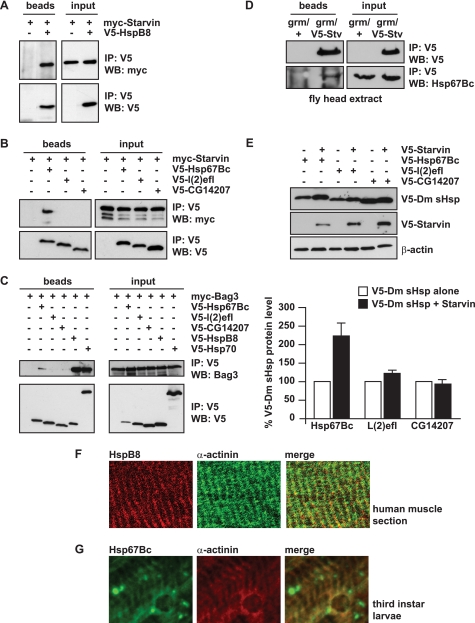

D. melanogaster HSP67Bc Interacts with Starvin and Human BAG3

We previously reported that, in human cells, HSPB8 forms a stable and stoichiometric complex with BAG3 (11). We first investigated whether human HSPB8 can interact with D. melanogaster Starvin. Myc-tagged Starvin and V5-tagged HSPB8 were co-expressed in HEK293 cells. Interestingly, notwithstanding the very low sequence homology between D. melanogaster Starvin and human BAG3 (supplemental Fig. 1B), we found that Starvin co-immunoprecipitates with HSPB8 (Fig. 1A). Thus, we investigated the ability of the three selected D. melanogaster small HSPs to interact with Starvin, in order to identify a D. melanogaster functional ortholog of human HSPB8. Fig. 1B shows that, among the three D. melanogaster sHSPs selected, HSP67Bc interacts with Starvin, whereas L(2)efl and CG14207 showed very weak or no interaction. We next tested the ability of HSP67Bc, L(2)efl, or CG14207 to interact with human BAG3. As expected, BAG3 binds to HSPB8 and human HSP70, both used as positive controls (Fig. 1C); BAG3 also showed a clear interaction with HSP67Bc, whereas no detectable binding of BAG3 to L(2)efl or CG14207 was observed. To further investigate the interaction between endogenous HSP67Bc and Starvin, in vivo, we developed a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for HSP67Bc. Interaction between endogenous HSP67Bc and overexpressed V5-tagged Starvin could be further confirmed in vivo, using fly head protein extracts from a transgenic line expressing V5-Starvin in the eyes under the control of the gmr-GAL4 driver (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

D. melanogaster HSP67Bc is a functional ortholog of human HSPB8. A and B, human HSPB8 and Dm-HSP67Bc co-immunoprecipitate with Dm-Starvin. HEK-293T cells were transfected with vectors encoding for D. melanogaster Myc-Starvin alone or together with either V5-HSPB8, V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, or V5-CG14207. 24 h post-transfection, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an antibody against the V5 tag, and the immunoprecipitated complexes were analyzed by Western blotting (WB) using V5- and Myc-specific antibodies. Among the D. melanogaster sHSPs analyzed, HSP67Bc interacts with Dm-Starvin (B), similarly to human HSPB8 (A). C, like HSPB8, Dm-HSP67Bc also binds to BAG3, the human functional ortholog of Dm-Starvin. HEK293 cells were transfected with vectors encoding for human Myc-BAG3 alone or together with either V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, V5-CG14207, or V5-HSPB8 and V5-HSP70, both used as positive controls and subjected, 24 h post-transfection, to immunoprecipitation with a V5-specific antibody. D, endogenous Hsp67Bc interacts with Starvin in vivo in fly head extracts. V5-starvin was expressed in flies under the control of the grm-GAL4 driver. Immunoprecipitation with a specific V5 antibody was carried out using fly head protein extracts from control flies (grm/+) and flies expressing V5-Starvin (gmr/V5-Stv). Interaction of endogenous Hsp67Bc with V5-Starvin was investigated by Western blotting using a specific rabbit polyclonal Hsp67Bc antibody. E, total levels of HSP67Bc are increased when it is co-expressed with Starvin. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected with vectors encoding for V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, and V5-CG14207 alone or in combination with V5-Starvin. The protein expression levels were analyzed by Western blotting 48 h post-transfection (average values ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 3–4 independent samples). F, human muscle tissue section showing that endogenous HSPB8 colocalizes with α-actinin at the Z band. G, endogenous Dm-HSP67Bc colocalizes with α-actinin at the Z band in third instar larvae muscles.

We also previously showed that HSPB8 stability is dramatically affected by its interaction with BAG3 because HSPB8 protein levels are significantly higher when it is co-transfected with BAG3 (11). Similarly, we show here that, in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells, co-transfection of Starvin with HSP67Bc results in higher steady-state protein levels of HSP67Bc (Fig. 1E). No major differences in L(2)efl or CG14207 expression levels were observed when co-transfecting them with either an empty vector or Starvin (Fig. 1E).

Altogether, these findings suggest that of the three Dm-HSPs tested here, Dm-HSP67Bc mostly resembles the characteristics of human HSPB8. However, while this study was ongoing, it was proposed that CG14207 might be the functional ortholog of human HSPB8 based on the localization of CG14207 at the Z band (50), a structure where also Starvin is found. However, we show here that human HSPB8 also colocalizes with the Z band marker α-actinin in human muscle tissue (Fig. 1F) and that, like CG14207, also endogenous HSP67Bc colocalizes with α-actinin in third instar larvae muscle (Fig. 1G). The localization of both CG14207 and HSP67Bc at the Z band implies that the identification of the D. melanogaster ortholog of human HSPB8 cannot be based only on its expression and distribution in muscle.

HSP67Bc and Starvin Induce LC3 Lipidation

To further identify the D. melanogaster ortholog of human HSPB8, we next used a number of functional end points. We previously showed that overexpression of HSPB8 alone or together with BAG3 results in stimulation of autophagy even in the absence of any other exogenously added misfolded or mutated protein (11). In human cells, HSPB8 overexpression causes both an increase in the total levels of LC3 I and II and an increase in LC3 II/LC3 I ratios (Fig. 2A), the most important indicator of autophagy; such an effect is also observed (although to a lesser extent) upon BAG3 overexpression (data not shown). We thus tested whether HSP67Bc, L(2)efl, or CG14207 also can stimulate autophagy. Similarly to HSPB8, HSP67Bc expression in mammalian cells increases both LC3 II and LC3 I levels (Fig. 2, B and C) and the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio (Fig. 2D). In contrast, expression of L(2)efl or CG14207 did not significantly affect LC3 lipidation (Fig. 2, A–D). Although the reason for the HSPB8- and HSP67Bc-mediated increase in total LC3 I and II levels (and how this may contribute to their role in autophagy) remains unclear, this finding plus the increase in LC3 II/LC I ratios by both proteins further suggests that Dm-HSP67Bc is the closest functional homolog of human HSPB8. In addition, like human BAG3, expression of Starvin alone could stimulate LC3 lipidation (Fig. 2, C and D), further supporting our assumption that Starvin represents the D. melanogaster functional ortholog of human BAG3. The effect of HSP67Bc alone or together with Starvin on the induction of autophagy was further explored by measuring the lipidation turnover (51). In human cells, the HSPB8-BAG3 complex stimulates the turnover of the autophagic vacuoles because levels of LC3 II increased upon inhibition of the final stage of autophagy (fusion of the autophagosomes with lysosomes) (11). Here, we expressed HSP67Bc alone or with Starvin in HEK293T cells. At 36 h after transfection, the lysosomal inhibitors E64d and pepstatin A were added. This led to a further increase in the levels of LC3 II in cells expressing HSP67Bc alone or together with Starvin and confirmed that the turnover of the autophagic vacuoles is stimulated by their ectopic expression (Fig. 2E).

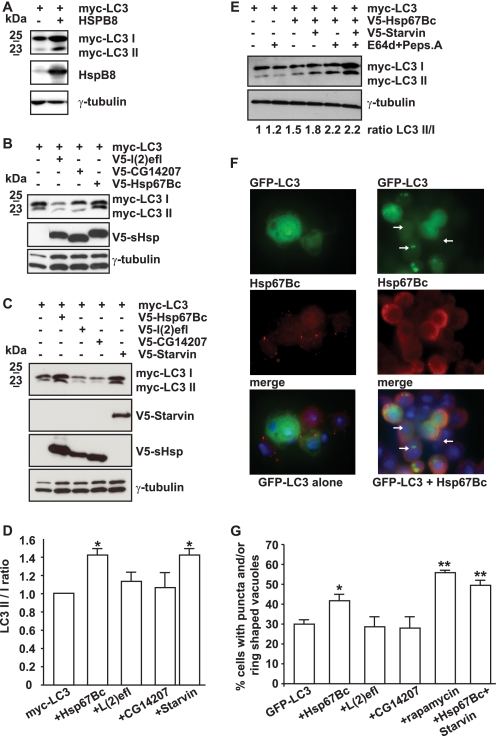

FIGURE 2.

HSP67Bc and Starvin induce LC3 lipidation both in mammalian and Drosophila Schneider S2 cells. A, HSPB8 overexpression leads to an increase in the total LC3 I and LC3 II levels. HEK293T cells were transfected with vectors encoding for Myc-LC3 alone or together with human HSPB8. 44 h post-transfection, the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using Myc- and HSPB8-specific antibodies. B–D, HEK293T cells were transfected with vectors encoding for Myc-LC3 alone or together with either V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, V5-CG14207, or V5-Starvin. 44 h post-transfection, the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using Myc- and V5-specific antibodies. Endogenous levels of γ-tubulin were measured as loading control. B and C, HSP67Bc and Starvin, but not L(2)efl or CG14207, induce LC3 lipidation. D, quantification of the effect of Hsp67Bc, L(2)efl, CG14207, and Starvin on the LC3 II/LC I ratio. *, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 3–4 independent samples. E, overexpression of HSP67Bc alone or together with Starvin induces the turnover of LC3. Where indicated (+), cells were treated for 6 h with the lysosomal inhibitors pepstatin A and E64d prior to extraction. Quantification of the effect of the lysosomal inhibitors on the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio (normalized against γ-tubulin) in cells transfected for 36 h is shown. F and G, overexpression of HSP67Bc alone or together with Starvin significantly increases the number of S2 cells containing GFP-LC3-positive punctae or ring-shaped vacuole-like structures. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected with vectors encoding for GFP-LC3 alone or together with either V5-HSP67Bc, V5-L(2)efl, V5-CG14207, or V5-Starvin or with both V5-HSP67Bc and V5-Starvin. 24 h post-transfection, cells were either left untreated or treated with rapamycin (5 μm) for 180 min and then fixed with formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. F, low magnification image showing the induction of GFP-LC3-positive autophagic vacuoles (white arrows) by HSP67Bc. G, the number of cells containing GFP-LC3-positive punctae and/or vacuole-like structures was counted. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001; average values ± S.E. of n = 4–11 independent samples.

The effects of the three D. melanogaster small HSPs on autophagy were finally tested in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells, using GFP-LC3 as an autophagy marker and counting the number of cells characterized by the presence of GFP-LC3-positive punctae and/or ring-shaped (vacuole-like) structures (52) (Fig. 2, F and G). Again, only HSP67Bc, and neither L(2)efl nor CG14207, increased the fraction of cells with positive punctae and/or ring-shaped structures (Fig. 2, F and G). Cotransfection of Starvin with HSP67Bc even further increased autophagy activation, similar to what we found previously when combining HSPB8 and BAG3 (11). The levels of autophagy induction under such conditions were found to be comparable with what is observed following treatment with the drug rapamycin, a well known stimulator of autophagy (Fig. 2G) (53). All together, these functional data strongly suggest that Dm-HSP67Bc and human HSPB8, with their respective partners Dm-Starvin and human BAG3, form orthologous complexes that play a role in the modulation of the autophagic degradation pathway.

HSP67Bc Decreases Mutated Polyglutamine Protein Total Levels and Aggregation in Cells

We recently showed that HSPB8 decreases the accumulation and aggregation of mutated polyglutamine proteins in mammalian cells (11, 33, 39). This occurs through the activation of the eIF2α pathway (33). Besides stimulating autophagy, activation of this pathway results in protein synthesis inhibition (54–56), and consistently, we found that co-expression of HSPB8 not only reduces the aggregation of the mutated polyglutamine protein huntingtin, but it also decreases its soluble levels (33). To further identify the functional ortholog of human HSPB8, we therefore tested the effect of HSP67Bc, L(2)efl, and CG14207 on the accumulation of soluble and aggregated levels of a mutated form of huntingtin with 128 glutamine residues (V5-Htt128Q) in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells. Surprisingly, both HSP67Bc and L(2)efl significantly reduced the soluble levels of V5-Htt128Q (running gel), whereas CG14207 had no effect (Fig. 3, A and C). In contrast, only HSP67Bc, and not L(2)efl or CG14207, reduced the amount of aggregated high molecular weight V5-Htt128Q retained in the stacking gel (Fig. 3, A and B). These data suggest that both HSP67Bc and L(2)efl may act through the induction of the eIF2α pathway, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis and decreasing the SDS-soluble levels of V5-Htt128Q, whereas only HSP67Bc, which also induces autophagy (Fig. 2), can facilitate V5-Htt128Q degradation and therefore decreases its aggregation. Indeed, overexpression of both HSP67Bc and L(2)efl, but not of CG14207, significantly increased the levels of phospho-eIF2α (Fig. 3, D and E).

In human cells, it was previously shown that impairment of eIF2α phosphorylation decreases the ability of the cells to cope with mutated polyglutamine proteins (57). To further investigate the implication of the eIF2α pathway in the function of HSP67Bc and L(2)efl, we first had to analyze the role of the eIF2α pathway in protein quality control in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells. We co-transfected a form of mutated huntingtin containing 74 glutamine residues (GFP-Htt74Q), which does not significantly aggregate in S2 cells within 72 h, with a vector encoding either Myc-tagged human wild-type (WT) eIF2α or Myc-tagged non-phosphorylatable S51A mutant eIF2α (Fig. 4A). Clearly, expression of the S51A mutant of eIF2α caused a significant increase in the total amount of mutated huntingtin (Fig. 4A), consistent with its dominant negative action. These results indicate that, as in mammalian cells, also in Drosophila Schneider cells, the eIF2α pathway plays a role in protein quality control. Having confirmed this, we next investigated whether the reduction of the soluble levels of V5-Htt128Q (running gel) observed upon expression of HSP67Bc and L(2)efl could be mediated by eIF2α. To efficiently block the activation of the eIF2α pathway, we first used the general inhibitor GADD34, which facilitates phospho-eIF2α dephosphorylation (58). We subcloned the D. melanogaster functional ortholog of GADD34 (here referred to as Dm-GADD34) and co-transfected it with V5-Htt128Q and the three selected small HSPs. Interestingly, both the effect of L(2)efl and HSP67Bc on soluble levels of V5-Htt128Q were largely reduced upon co-expression of Dm-GADD34 (Fig. 4B). Likewise, the effect of both Starvin and HSP67Bc on LC3 lipidation as a marker of autophagy induction was completely blocked by co-expression of GADD34 and inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). As another approach to block the eIF2α pathway, we co-expressed the dominant-negative non-phosphorylatable S51A mutant of eIF2α with HSP67Bc. This completely abrogated the ability of HSP67Bc to decrease both V5-Htt128Q soluble (running) and insoluble (stacking) levels (Fig. 4D).

These combined data show that both HSP67Bc and L(2)efl can activate the eIF2α pathway. However, it is only in the case of HSP67Bc that this leads not only to a block of protein synthesis but also to the induction of autophagy, required to suppress mutated huntingtin aggregation (Fig. 4, E and F). This difference with L(2)efl seems related to the fact that HSP67Bc does and L(2)efl does not form a complex with Starvin (Fig. 1). Thus, based on our functional studies, Dm-HSP67Bc, and not L(2)efl or CG14207, is the closest functional ortholog of human HSPB8.

Both HSP67Bc and HSPB8 Inhibit Mutated Polyglutamine-mediated Eye Degeneration in Vivo

Our results show that in mammalian and Drosophila S2 cells, human HSPB8 and Dm-HSP67Bc decrease mutated polyglutamine aggregation. We next asked whether they could exert a protective effect in vivo, using a well established fly model of spinocerebellar ataxia 3 (35). This fly model expresses a mutated form of ataxin 3 with 78 glutamine repeats (SCA3(78)Q) in the eyes under the control of the eye-specific gmr-GAL4 driver and shows progressive eye degeneration, visualized by the presence of dark patches and collapsed eyes. We then generated transgenic fly lines expressing human HSPB8 or V5-tagged Dm-HSP67Bc under the control of the pUAS promoter and compared the effect on SCA3(78)Q-mediated toxicity. Fig. 5A shows that all of the transgenic fly lines generated express HSPB8 at comparable levels. All fly lines expressing HSPB8 could significantly decrease the SCA3(78)Q-mediated eye degeneration (quantified as the percentage of eyes collapsed and/or with dark patches compared with control flies; Fig. 5, D and E), similar to its D. melanogaster functional ortholog V5-HSP67Bc (see Fig. 5B for expression levels). As an additional control, we included in our study two independent fly lines expressing RNAi sequences that efficiently down-regulated HSP67Bc expression (Fig. 5C). This knockdown of HSP67Bc significantly worsened the SCA3 degenerative eye phenotype (Fig. 5D). Combined with our previous and current in vitro data (11, 33), these in vivo data not only further suggest that HSP67Bc is indeed a functional ortholog HSPB8 but also suggest that increases or decreases of HSP67Bc/HSPB8 activity, respectively, ameliorate or aggravate folding diseases. Moreover, these results also strongly suggest that HSPB8 and HSP67Bc are modifiers of SCA3.

Mutated HSPB8 K141E and, to a Lesser Extent, K141N Show a Partial Loss of Function Phenotype and Impair HSPB8 Protective Role toward Mutated Polyglutamine Proteins in Vitro and/or in Vivo

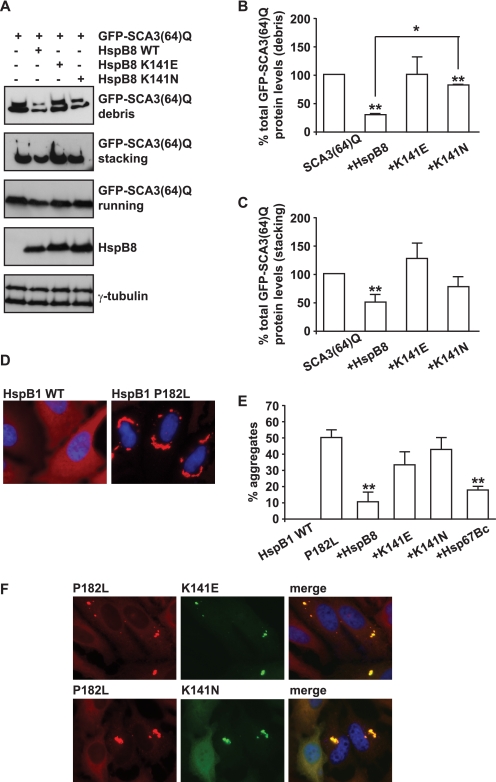

After having established HSPB8 as a possible modifier of a dominant genetic disease like SCA3, we investigated what the consequences are of the missense mutations (K141E and K141N) in human HSPB8, which are associated with peripheral neuropathy (16, 17). First, we used a cell model expressing human ataxin 3 with 64 glutamine residues (SCA3(64)Q). The levels of SCA3(64)Q accumulating in the debris fraction (cellular medium) were used as a measure of ataxin 3-mediated toxicity. Whereas wild-type HSPB8 significantly decreased the amount of mutated ataxin 3 in the debris, the mutated form K141E did not, and the activity of the mutated form K141N was significantly decreased (Fig. 6, A and B). Also, in contrast to wild-type HSPB8, both mutated forms of HSPB8 were unable to significantly decrease the amount of high molecular weight, aggregated SCA3(64)Q (Fig. 6, A and C). These data strongly suggest that both K141E and K141N mutations impair HSPB8 function in protein quality control. This was further analyzed in cells using another aggregate-prone substrate, the P182L mutant of HSPB1, which is associated with peripheral neuropathy (15). As previously described, the P182L mutant of HSPB1 is highly unstable and aggregates in cells (Fig. 6, D and E) (15, 59). Similarly to what was observed using SCA3(64)Q, we found that overexpression of both human wild-type HSPB8 or Dm-HSP67Bc could significantly decrease the aggregation of P182L-HSPB1 (Fig. 6E). In contrast, both K141E and K141N were unable to prevent the aggregation of P182L-HSPB1 (Fig. 6E). Interestingly, K141E and K141N largely colocalized with P182L-HSPB1 aggregates (Fig. 6F), suggesting a failed attempt of K141E and K141N to prevent P182L-HSPB1 aggregation.

FIGURE 6.

In cells, the K141E and K141N mutations show impaired ability to decrease the aggregation of the two misfolded substrates SCA3(64)Q and P182L-HSPB1 as compared with wild-type HSPB8. A–C, K141E and K141N are less efficient than wild-type HSPB8 in decreasing mutated ataxin 3 aggregation and mediated toxicity. HEK293T cells were transfected with vectors encoding for SCA3(64)Q alone or together with either wild-type HSPB8, K141E, or K141N. 48 h post-transfection, the medium (debris) and the cells were collected, and total proteins from both fractions were extracted. SCA3(64)Q soluble (running) and insoluble (stacking) levels were analyzed. B and C, total levels of GFP-SCA3(64)Q were quantified (*, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 3 independent samples). D and E, K141E and K141N are less efficient than wild-type HSPB8 in decreasing mutated P182L-HSPB1 aggregation. HeLa cells were transfected with vectors encoding for wild-type or P182L-HSPB1 or with vectors encoding for P182L-HSPB1 alone or in combination with wild-type Myc-HSPB8, Myc-K141E, Myc-K141N, or wild-type Myc-HSP67Bc. 72 h post-transfection, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and processed for immunofluorescence with specific antibodies. E, the number of cells showing HSPB1 aggregates was counted (*, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. of n = 3–5 independent samples; more than 100 cells/sample were counted). F, mutated K141E and K141N colocalize with aggregated P182L-HspB1.

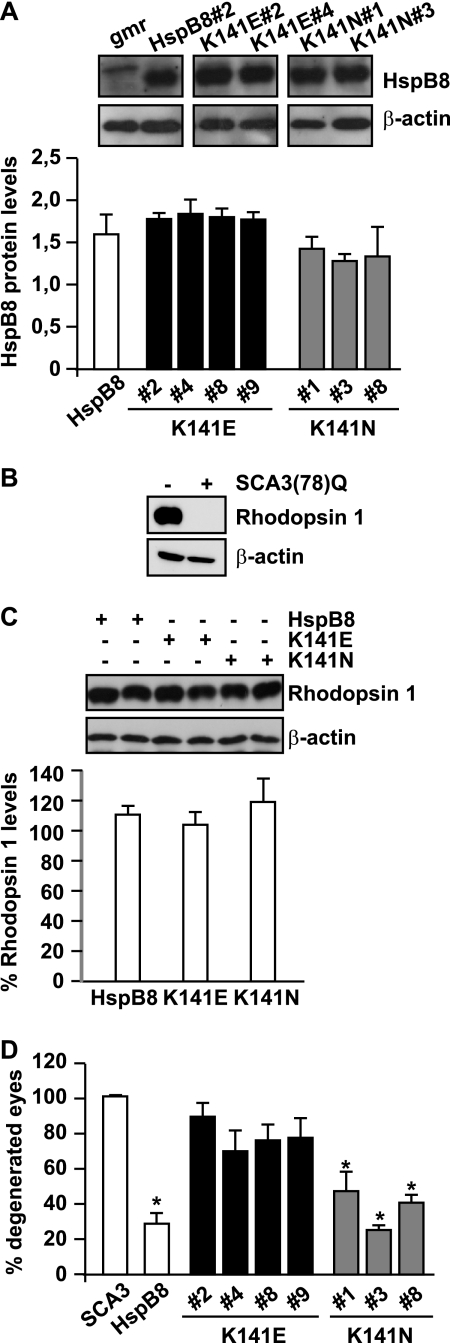

The impact of K141E and K141N mutations on HSPB8 ability to protect against mutated SCA3-induced toxicity was further investigated in vivo, using the SCA3 fly model. We generated transgenic fly lines expressing human K141E or K141N HSPB8 under the control of the pUAS promoter. The gmr-GAL4-driven overexpression of the K141E and K141N mutated forms of HSPB8 was as high as that in flies expressing wild-type HSPB8 (Fig. 7A) and did not by itself induce any detectable morphological sign of degeneration because we observed no rough eye phenotype up to 20 days after eclosion (data not shown). As another end point, we measured expression levels of rhodopsin 1, one of the major proteins expressed in the rhabdomeres of photoreceptor cells (60, 61), the levels of which are affected under degenerative conditions (62), including expression of SCA3(78)Q (Fig. 7B). All fly lines expressing the mutated HSPB8 (K141E or K141N) alone had rhodopsin 1 levels comparable with the ones found in flies expressing wild-type HSPB8. Thus, the sole expression of mutated HSPB8 in the eyes did not cause any detectable sign of toxicity. Knowing that the mutated forms of HSPB8 alone had no effect allowed us to test whether or not they were still able to decrease SCA3-mediated eye degeneration. We thus crossed the fly lines expressing K141E, K141N, or wild-type HSPB8 with flies expressing SCA3(78Q). Whereas wild-type HSPB8 reduced SCA3(78Q)-mediated eye degeneration by over 60% (Fig. 5D), the K141E mutated form of HSPB8 showed an almost complete loss of its protective function (Fig. 7D). The K141N mutated form of HSPB8 retained a significant part of its activity, as compared with wild-type HSPB8, but also for this mutant, a slight decrease in neuroprotective activity could be observed. All of these results are in line with the cellular data obtained using the two aggregate-prone substrates SCA3(64)Q and P182L-HSPB1, where K141E shows a major loss of function, whereas K141N shows only a partial loss of function in protein quality control.

FIGURE 7.

The K141E mutation significantly affects HSPB8 protective effect on SCA3-induced eye degeneration. A, quantification of gmr-GAL4-driven HSPB8 protein expression in 1–3-day-old fly head extracts (mean ± S.E. (error bars); n = 3–7). Expression of human wild-type HSPB8 (transgenic line 2), used as control, mutated HSPB8 K141E (transgenic lines 2, 4, 8, and 9) and K141N (transgenic lines 1, 3, and 8). gmr, gmr-GAL4/+; HSPB8#2, gmr-GAL4/UAS-HSPB8#2; K141E#2, gmr-GAL4/UAS-HSPB8-K141E#2, etc.; K141N#1, gmr-GAL4/UAS-HSPB8-K141N#1, etc. B, rhodopsin 1 levels are decreased below detectable levels in SCA3(78)Q-flies and can be used as a marker for eye degeneration. Protein extracts from 1–2-day-old fly heads, with corresponding genotypes: −, CyO/+; +, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3 (78Q)/+. C, overexpression of mutated HSPB8 alone does not significantly affect rhodopsin 1 levels. Protein extracts were prepared from 20 days old fly heads. Western blotting of two representative samples per group and quantification of rhodopsin 1 levels normalized against β-actin show no significant decrease upon overexpression of mutated HSPB8, as compared with wild-type HSPB8 (rhodospin 1 levels from 3–4 independent lines expressing either wild-type HSPB8 or K141E or K141N were quantified, and measures were pooled; mean ± S.E.; n = 7–13). Genotypes were as described in the legend to Fig. 6A. D, mutations of HSPB8 decrease its ability to protect against mutated SCA3-mediated eye degeneration. Shown is a quantification of eye degeneration in flies overexpressing either SCA3(78Q) alone or in combination with wild-type or mutated, K141E or K141N, HSPB8; total number of eyes scored: 200–300; *, p < 0.05 as compared with SCA3; average values ± S.E. of n = 3 independent experiments. SCA3, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/+; HSPB8, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/UAS-HSPB8#2; K141E#2, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/UAS-HSPB8-K141E#2, etc; K141N#1, gmr-GAL4-UAS-SCA3(78Q)/UAS-HSPB8-K141N#1, etc.

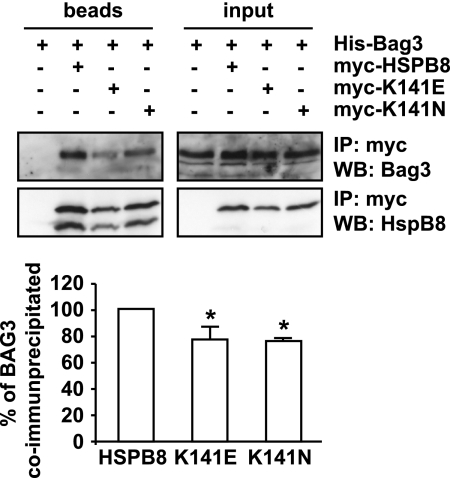

We next asked whether the decreased efficiency of K141E and K141N to inhibit mutated protein aggregation in cells and to protect against mutated SCA3-induced eye degeneration in vivo could be ascribed to a different ability to interact with BAG3 and/or induce autophagy. As shown previously, in cells depleted of BAG3, HSPB8 is unable to clear polyglutamine protein aggregates through the autophagic pathway (11). Consistently, both mutated forms of HSPB8 were found to co-immunoprecipitate less efficiently with BAG3 as compared with wild-type HSPB8 (Fig. 8A). This decrease in K141E and K141N binding to BAG3 could partially explain why the mutated forms of HSPB8 show a partial loss of function.

FIGURE 8.

The K141E and K141N mutated forms bind less strongly to BAG3 than wild-type HSPB8. HEK-293T cells were transfected with vectors encoding for His-BAG3 alone or together with either Myc-HSPB8, Myc-K141E, or Myc-K141N. 24 h post-transfection, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an antibody against the Myc tag, and the immunprecipitated complexes were analyzed by Western blotting using BAG3- and HSPB8-specific antibodies. *, p < 0.05; average values ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Accumulation of aggregated proteins is a pathological hallmark of neurodegenerative disorders, (e.g. Alzheimer disease, spinocerebellar ataxia 3, and Huntington disease) (1, 2), and it is also often observed in muscular disorders (protein aggregate myopathies; e.g. desmin-related myopathy and muscular dystrophy) (4–6) and peripheral neuropathies (e.g. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A) (3, 27). Genetic and molecular studies have shown a causal role of protein misfolding in cellular death, and experimental approaches have demonstrated that inhibition of protein misfolding (by up-regulation of molecular chaperones) and stimulation of aggregated substrate degradation (through autophagy) can decrease degeneration (7–10). These findings underscore the importance of a proper and functional protein quality control system to protein conformation disorders.

In this study, we identified Dm-HSP67Bc as the closest functional ortholog of human HSPB8. Recently, CG14207 was suggested to be the D. melanogaster ortholog of human HSPB8 (50), mainly based on its localization at the Z bands in muscles, a structure in which Starvin is also enriched. However, we show here that also HSP67Bc colocalizes with α-actinin at the Z bands, thus making it difficult to establish functional homology mainly on the basis of subcellular localization. We present here both biochemical and functional evidence that Dm-HSP67Bc, and not CG14207 or L(2)efl, is the closest HSPB8 ortholog; only HSP67Bc interacts with human BAG3, and Dm-Starvin, the sole D. melanogaster BAG protein (34), stimulates autophagy in an eIF2α-dependent manner and decreases mutated polyglutamine protein aggregation in cells. Furthermore, like human HSPB8, Dm-HSP67Bc protected against mutated polyglutamine-mediated eye degeneration in a SCA3 fly model in vivo. Inversely, knockdown of Dm-HSP67Bc worsened the mutated ataxin 3-mediated eye degeneration in vivo, in line with our previous finding that HSPB8-BAG3-deficient cells show a decreased ability to stimulate autophagy and to cope with mutated huntingtin (11). Our results also strongly suggest that up-regulation of HSPB8 activity might be used as a general defense against disease-associated misfolded or aggregation-prone proteins. Thus, induction of HSPB8-BAG3 expression and function may represent a valid therapeutic tool in such diseases. In addition, recent data have revealed that BAG3 expression levels are increased during aging. This was suggested to be an adaptive and compensatory response required during normal aging (63), a condition characterized by the accumulation of misfolded proteins or small aggregates that cannot be handled by the proteasome. This also implies that small decreases in the expression or function of the HSPB8-BAG3 complex, as found here for the two missense mutations of HSPB8 (K141E and K141N) that are associated with dominant hereditary peripheral neuropathy, may contribute to disease progression.

Mutations in several other members of the HSPB family (e.g. HSPB1, HSPB4, and HSPB5) that are associated with a number of neurological and muscular disorders and/or with cataract (6, 15–18), have all been associated with protein aggregation. At least for mutated HSPB5, which is associated with desmin-related myopathy, both a loss and toxic gain of function have been suggested to play a role in disease pathogenesis (6). Our data demonstrate that the K141E mutant and, partially, the K141N mutant of HSPB8 are characterized by a loss of function. The (partial) loss of function may, at least in part, be explained by our observation that both mutated forms of HSPB8 bind less efficiently to BAG3, as compared with the wild-type protein. This hypothesis is supported by our earlier findings that HSPB8 cannot facilitate clearance of protein aggregates in cells lacking BAG3 (11) and is consistent with our current findings that Dm-L(2)efl, which can induce eIF2α phosphorylation but cannot bind to BAG3, is unable to support aggregate clearance by autophagy (Figs. 2–4).

Our findings that the gmr-GAL4-driven expression of mutated HSPB8 in the eye (in the absence of any other exogenous misfolded protein) did not cause any morphological sign of degeneration and did not decrease rhodopsin 1 levels seem not to support a major negative gain of function of the mutated forms of HSPB8. Also, when co-expressed with mutated ataxin 3, neither K141E nor K141N HSPB8 caused an increase in eye degeneration, as could be expected for two independently aggregating proteins. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that the mutated forms of HSPB8 may also have acquired a toxic gain of function that could contribute to disease. One must realize that, in humans, the K141E and K141N mutations of HSPB8 result in peripheral neuropathy and muscular atrophy, without affecting the structure and function of the eyes (16). This suggests that the eyes might be less vulnerable, as compared with peripheral neurons and muscular cells, to the altered activity of mutated HSPB8. Given the relatively high expression levels of HSPB8 in peripheral neurons and muscle, a mild toxic gain of function may indeed also contribute to disease. In fact, a (mild) toxic gain of function even may be linked to the observed partial loss of function, and it can be speculated that such effects are related to the difference in the degree of loss of function of K141E and K141N observed in cells and in vivo. The presence of the mutated forms of HSPB8 in perinuclear aggregates in cells (16) and the association of HSPB8 mutants with aggregates of P182L-HSPB1 (Fig. 6E) may also be taken as further support for a dominant toxic gain of function. However, this may also merely reflect a failed attempt of K141E and K141N to process P182L-HSPB1 toward degradation. In vitro studies on the stability of the mutated forms of HSPB8 and in vivo studies using tissue-specific promoters in Drosophila combined with different read-out systems will be required to further address these questions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. N. Bonini for providing the gmr-GAL4 SCA3trQ78 fly model of SCA3, Dr. F. Bosveld for technical assistance in generation of the fly lines, and Prof. J. Landry and H. Lambert for collaboration and technical assistance in the preparation of the HSP67Bc rabbit polyclonal antibody. We also thank Dr. W. F. A. den Dunnen and Dr. J. Vinet for providing human muscular tissue sections and for technical assistance in their staining.

This work was supported by the National Ataxia Foundation Young Investigator Award, by the Marie Curie International Reintegration and the Prinses Beatrix Foundation/Dutch Huntington Association WAR09-23 (to S. C.), by a VIDI grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research NWO (917-36-400), by NWO Middelgroot Grant 911-06-001 (to O. C. M. S.), by Senter (IOP Genomics Grant IGE03018), and by the Prinses Beatrix Foundation WAR05-0129 (to H. H. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

M. Vos, S. Carra, B. Kanon, F. Bosveld, K. Klouke, O. Sibon, and H. Kampinga, manuscript submitted for publication.

- HSP

- heat shock protein

- SCA3

- spinocerebellar ataxia 3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cummings C. J., Zoghbi H. Y. (2000) Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 1, 281–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross C. A., Poirier M. A. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, (suppl.) S10–S17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortun J., Go J. C., Li J., Amici S. A., Dunn W. A., Jr., Notterpek L. (2006) Neurobiol. Dis. 22, 153–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujita E., Kouroku Y., Isoai A., Kumagai H., Misutani A., Matsuda C., Hayashi Y. K., Momoi T. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 618–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma M. C., Goebel H. H. (2005) Neurol. India 53, 273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vicart P., Caron A., Guicheney P., Li Z., Prévost M. C., Faure A., Chateau D., Chapon F., Tomé F., Dupret J. M., Paulin D., Fardeau M. (1998) Nat. Genet. 20, 92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soto C. (2003) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muchowski P. J., Wacker J. L. (2005) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravikumar B., Vacher C., Berger Z., Davies J. E., Luo S., Oroz L. G., Scaravilli F., Easton D. F., Duden R., O'Kane C. J., Rubinsztein D. C. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36, 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warrick J. M., Chan H. Y., Gray-Board G. L., Chai Y., Paulson H. L., Bonini N. M. (1999) Nat. Genet. 23, 425–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carra S., Seguin S. J., Lambert H., Landry J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1437–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chowdary T. K., Raman B., Ramakrishna T., Rao C. M. (2004) Biochem. J. 381, 379–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morimoto R. I. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 1427–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kappé G., Franck E., Verschuure P., Boelens W. C., Leunissen J. A., de Jong W. W. (2003) Cell Stress Chaperones 8, 53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evgrafov O. V., Mersiyanova I., Irobi J., Van Den Bosch L., Dierick I., Leung C. L., Schagina O., Verpoorten N., Van Impe K., Fedotov V., Dadali E., Auer-Grumbach M., Windpassinger C., Wagner K., Mitrovic Z., Hilton-Jones D., Talbot K., Martin J. J., Vasserman N., Tverskaya S., Polyakov A., Liem R. K., Gettemans J., Robberecht W., De Jonghe P., Timmerman V. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36, 602–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irobi J., Van Impe K., Seeman P., Jordanova A., Dierick I., Verpoorten N., Michalik A., De Vriendt E., Jacobs A., Van Gerwen V., Vennekens K., Mazanec R., Tournev I., Hilton-Jones D., Talbot K., Kremensky I., Van Den Bosch L., Robberecht W., Van Vandekerckhove J., Van Broeckhoven C., Gettemans J., De Jonghe P., Timmerman V. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36, 597–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang B. S., Zhao G. H., Luo W., Xia K., Cai F., Pan Q., Zhang R. X., Zhang F. F., Liu X. M., Chen B., Zhang C., Shen L., Jiang H., Long Z. G., Dai H. P. (2005) Hum. Genet. 116, 222–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litt M., Kramer P., LaMorticella D. M., Murphey W., Lovrien E. W., Weleber R. G. (1998) Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 471–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner L. E., Garcia C. A., Lupski J. R. (1999) Annu. Rev. Med. 50, 263–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saifi G. M., Szigeti K., Wiszniewski W., Shy M. E., Krajewski K., Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I., Kochanski A., Reeser S., Mancias P., Butler I., Lupski J. R. (2005) Hum. Mutat. 25, 372–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Street V. A., Bennett C. L., Goldy J. D., Shirk A. J., Kleopa K. A., Tempel B. L., Lipe H. P., Scherer S. S., Bird T. D., Chance P. F. (2003) Neurology 60, 22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irobi J., Dierick I., Jordanova A., Claeys K. G., De Jonghe P., Timmerman V. (2006) Neuromolecular Med. 8, 131–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verhoeven K., De Jonghe P., Coen K., Verpoorten N., Auer-Grumbach M., Kwon J. M., FitzPatrick D., Schmedding E., De Vriendt E., Jacobs A., Van Gerwen V., Wagner K., Hartung H. P., Timmerman V. (2003) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 722–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Züchner S., Mersiyanova I. V., Muglia M., Bissar-Tadmouri N., Rochelle J., Dadali E. L., Zappia M., Nelis E., Patitucci A., Senderek J., Parman Y., Evgrafov O., Jonghe P. D., Takahashi Y., Tsuji S., Pericak-Vance M. A., Quattrone A., Battaloglu E., Polyakov A. V., Timmerman V., Schröder J. M., Vance J. M. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36, 449–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel P. I., Roa B. B., Welcher A. A., Schoener-Scott R., Trask B. J., Pentao L., Snipes G. J., Garcia C. A., Francke U., Shooter E. M., Lupski J. R., Suter U. (1992) Nat. Genet. 1, 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roa B. B., Garcia C. A., Pentao L., Killian J. M., Trask B. J., Suter U., Snipes G. J., Ortiz-Lopez R., Shooter E. M., Patel P. I., Lupski J. R. (1993) Nat. Genet. 5, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortun J., Dunn W. A., Jr., Joy S., Li J., Notterpek L. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 10672–10680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fortun J., Verrier J. D., Go J. C., Madorsky I., Dunn W. A., Notterpek L. (2007) Neurobiol. Dis. 25, 252–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doong H., Rizzo K., Fang S., Kulpa V., Weissman A. M., Kohn E. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28490–28500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takayama S., Xie Z., Reed J. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 781–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takayama S., Reed J. C. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, E237–E241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carra S., Seguin S. J., Landry J. (2008) Autophagy 4, 237–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carra S., Brunsting J. F., Lambert H., Landry J., Kampinga H. H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5523–5532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coulson M., Robert S., Saint R. (2005) Genetics 171, 1799–1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bilen J., Bonini N. M. (2007) PLoS Genet. 3, 1950–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyttenbach A., Carmichael J., Swartz J., Furlong R. A., Narain Y., Rankin J., Rubinsztein D. C. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2898–2903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabeya Y., Mizushima N., Ueno T., Yamamoto A., Kirisako T., Noda T., Kominami E., Ohsumi Y., Yoshimori T. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 5720–5728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brand A. H., Perrimon N. (1993) Development 118, 401–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carra S., Sivilotti M., Chávez Zobel A. T., Lambert H., Landry J. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 1659–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrow G., Tanguay R. M. (2003) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 14, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Homma S., Iwasaki M., Shelton G. D., Engvall E., Reed J. C., Takayama S. (2006) Am. J. Pathol. 169, 761–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrow G., Heikkila J. J., Tanguay R. M. (2006) Cell Stress Chaperones 11, 51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrow G., Samson M., Michaud S., Tanguay R. M. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 598–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michaud S., Morrow G., Marchand J., Tanguay R. M. (2002) Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 28, 79–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrow G., Inaguma Y., Kato K., Tanguay R. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31204–31210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michaud S., Marin R., Westwood J. T., Tanguay R. M. (1997) J. Cell Sci. 110, 1989–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marin R., Tanguay R. M. (1996) Chromosoma 105, 142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vos M. J., Zijlstra M. P., Kanon B., van Waarde-Verhagen M. A., Brunt E. R., Oosterveld-Hut H. M., Carra S., Sibon O. C., Kampinga H. H. (2010) Hum. Mol. Genet., in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giot L., Bader J. S., Brouwer C., Chaudhuri A., Kuang B., Li Y., Hao Y. L., Ooi C. E., Godwin B., Vitols E., Vijayadamodar G., Pochart P., Machineni H., Welsh M., Kong Y., Zerhusen B., Malcolm R., Varrone Z., Collis A., Minto M., Burgess S., McDaniel L., Stimpson E., Spriggs F., Williams J., Neurath K., Ioime N., Agee M., Voss E., Furtak K., Renzulli R., Aanensen N., Carrolla S., Bickelhaupt E., Lazovatsky Y., DaSilva A., Zhong J., Stanyon C. A., Finley R. L., Jr., White K. P., Braverman M., Jarvie T., Gold S., Leach M., Knight J., Shimkets R. A., McKenna M. P., Chant J., Rothberg J. M. (2003) Science 302, 1727–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arndt V., Dick N., Tawo R., Dreiseidler M., Wenzel D., Hesse M., Fürst D. O., Saftig P., Saint R., Fleischmann B. K., Hoch M., Höhfeld J. (2010) Curr. Biol. 20, 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanida I., Minematsu-Ikeguchi N., Ueno T., Kominami E. (2005) Autophagy 1, 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yano T., Mita S., Ohmori H., Oshima Y., Fujimoto Y., Ueda R., Takada H., Goldman W. E., Fukase K., Silverman N., Yoshimori T., Kurata S. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 908–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blommaart E. F., Luiken J. J., Blommaart P. J., van Woerkom G. M., Meijer A. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2320–2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harding H. P., Novoa I., Zhang Y., Zeng H., Wek R., Schapira M., Ron D. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 1099–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harding H. P., Zhang Y., Ron D. (1999) Nature 397, 271–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harding H. P., Zhang Y., Zeng H., Novoa I., Lu P. D., Calfon M., Sadri N., Yun C., Popko B., Paules R., Stojdl D. F., Bell J. C., Hettmann T., Leiden J. M., Ron D. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 619–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kouroku Y., Fujita E., Tanida I., Ueno T., Isoai A., Kumagai H., Ogawa S., Kaufman R. J., Kominami E., Momoi T. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14, 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Novoa I., Zeng H., Harding H. P., Ron D. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 1011–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ackerley S., James P. A., Kalli A., French S., Davies K. E., Talbot K. (2006) Hum Mol. Genet. 15, 347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Tousa J. E., Baehr W., Martin R. L., Hirsh J., Pak W. L., Applebury M. L. (1985) Cell 40, 839–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuker C. S., Cowman A. F., Rubin G. M. (1985) Cell 40, 851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurada P., O'Tousa J. E. (1995) Neuron 14, 571–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gamerdinger M., Hajieva P., Kaya A. M., Wolfrum U., Hartl F. U., Behl C. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 889–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]