Abstract

Nuclear processes such as transcription, DNA replication, and recombination are dynamically regulated by chromatin structure. Transcription is known to be regulated by chromatin-associated proteins containing conserved protein domains that specifically recognize distinct covalent post-translational modifications on histones. However, it has been unclear whether similar mechanisms are involved in mammalian DNA recombination. Here, we show that RAG2 – an essential component of the RAG1/2 V(D)J recombinase, that mediates antigen receptor gene assembly1 – contains a plant homeodomain (PHD) finger that specifically recognizes histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me3). The high-resolution crystal structure of the RAG2 PHD finger bound to H3K4me3 reveals the molecular basis of H3K4me3-recognition by RAG2. Mutations that abrogate RAG2's recognition of H3K4me3 severely impair V(D)J recombination in vivo. Reducing the level of H3K4me3 similarly leads to a decrease in V(D)J recombination in vivo. Notably, a conserved tryptophan residue (W453) that constitutes a key structural component of the K4me3-binding surface and is essential for RAG2's recognition of H3K4me3 is mutated in patients with immunodeficiency syndromes. Together our results identify a novel function for histone methylation in mammalian DNA recombination. Furthermore, our results provide the first evidence suggesting that disrupting the read-out of histone modifications can cause an inherited human disease.

Many studies suggest that V(D)J recombination is regulated by modulating the chromatin structure of antigen receptor loci during lymphoid development2. Several studies have analyzed the pattern of histone modifications present at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus during B cell development3-5. However, mechanisms linking histone modifications to the function of the RAG recombinase have remained elusive.

Since RAG2 contains a noncanonical plant homeodomain (PHD) finger6,7 – a module that can mediate interactions with chromatin8-10 – we asked whether a polypeptide encompassing the RAG2 PHD finger (RAG2PHD: aa 414-527) can recognize modified histone proteins. In an in vitro screen of peptide microarrays containing ~70 distinct modified histone peptides, we found that RAG2PHD specifically binds to histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) (Fig. 1a; Fig. S1; data not shown). The specificity of this interaction was confirmed by peptide pull-down assays (Fig. 1b; Fig. S2; Fig. S3). RAG2 has a C-terminal extension of 40 aa that is essential for phosphoinositide (PtdInsP)-binding7 (aa 488-527), but this region is dispensable for H3K4me3-binding as the minimal PHD finger alone (aa 414-487) is sufficient for H3K4me3-recognition (Fig. 1c). In addition, the acidic hinge region of RAG2 (aa 388-412), previously implicated in histone-binding11, is dispensable for recognition of H3K4me3 (Fig. 1d). Moreover, mutations in the acidic hinge region, which had previously been shown to interfere with histone binding11, had no effect on the H3K4me3 interaction (Fig. 1d). Using calf thymus histone protein pull-down assays, we confirmed that the interaction between RAG2PHD and H3K4me3 occurs in the context of full-length histone proteins (Fig. 1e). Further, RAG2PHD bound to native mononucleosomes purified from HeLa cells, but not mononucleosomes reconstituted from bacterially-expressed recombinant histones, indicating that the RAG2PHD-nucleosome interaction is dependent upon post-translational histone modifications (Fig. 1f). Although full-length RAG2 binds H3K4me3 peptides, core RAG2 (aa 1-387) – the minimal portion of RAG2 required for V(D)J cleavage in vitro – which lacks the PHD finger, does not (Fig. 1g). Consistent with the pull-down results, tryptophan fluorescence measurements using RAG2PHD determined dissociation constants (Kd) of ~4 μM for H3K4me3, ~60 μM for H3K4me2, ~120 μM for H3K4me1, and ~500 μM for H3K4me0 (Fig. S5). Thus, the RAG2 PHD finger is a chromatin-binding module that recognizes H3K4me3.

Fig. 1. The RAG2 PHD finger is a novel H3K4me3-binding module.

a, RAG2PHD preferentially binds H3K4me3 peptides. Peptide microarrays containing the indicated histone peptides were probed with Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-RAG2414-527 (RAG2PHD). Red spots indicate peptide binding by RAG2PHD. Integrity of peptides was previously confirmed9,17 (Fig. S4). H3, histone H3; H4, histone H4; aa, amino acids; me, methylation, ac, acetylation; ph, phosphorylation, s, symmetric, a, asymmetric b, Western blot analysis of histone peptide pull-downs with RAG2PHD and indicated biotinylated peptides. c, RAG2414-487 is sufficient for recognition of H3K4me3 in histone peptide pull-down assay as in b. GST alone is shown as a negative control. d, The RAG2 hinge region (aa 388-412) is dispensable for H3K4me3-recognition. Peptide pull-down assays as in b, with the indicated proteins. e, Western blot of RAG2PHD and GST control pull-downs from calf thymus histones. f, Gel shift comparing RAG2PHD binding to purified native HeLa nucleosomes (left panel) or nucleosomes reconstituted from recombinant, bacterially-expressed histone proteins (right panel). Ethidium-bromide stain of nucleosomal DNA on a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. g, Full-length RAG2, but not RAG2core recognizes H3K4me3. Peptide pull-down assays as in b, with the indicated proteins.

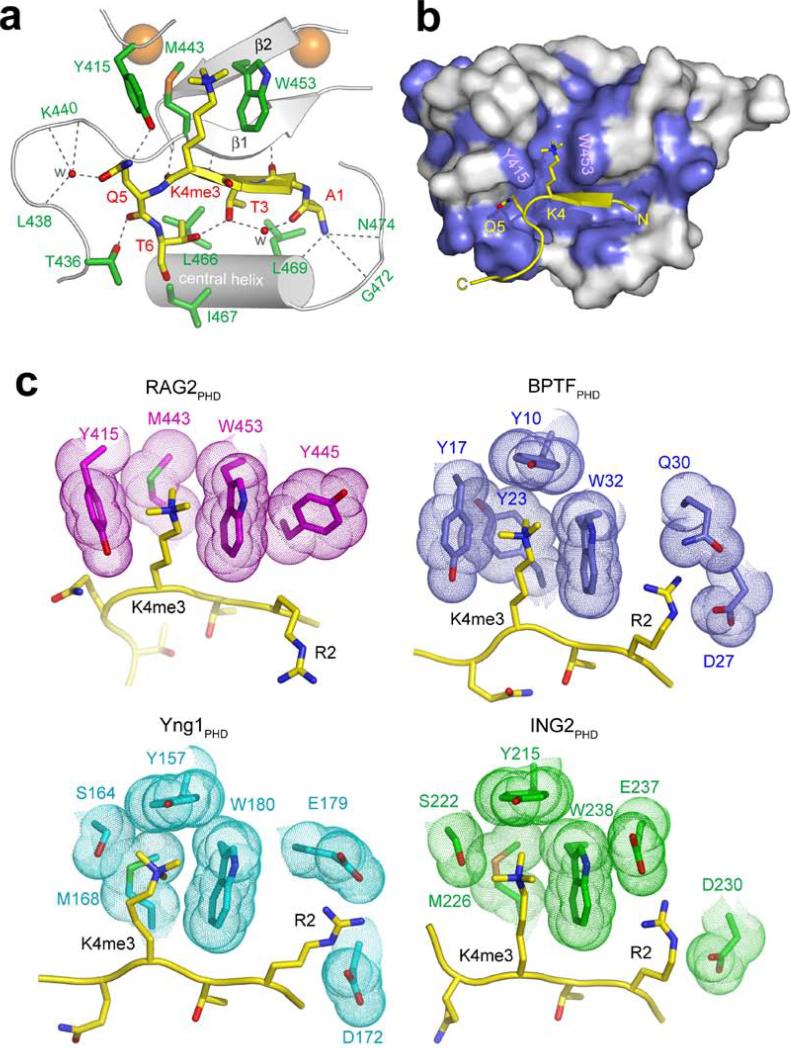

To understand the molecular basis of the interaction between the RAG2 PHD finger and H3K4me3, we determined the crystal structure of the RAG2PHD-H3K4me3 complex at 1.15 Å resolution (Fig. 2; Fig. S6; Table S1). In three previously published PHD-H3K4me3 structures12-14, the H3 peptide extends straight through the peptide-binding groove. However, in the RAG2PHD-H3K4me3 structure, the H3 peptide is kinked by ~90° at Q5. The K4me3 sidechain is recognized by cation-π interactions within an aromatic channel delimited by Y415 on the left, M443 on the back, and W453 on the right (Fig. 2a). Despite not revealing any primary sequence conservation with the K4me3-binding residues of ING2, BPTF and YNG1 (Fig. S7), RAG2 forms a similar K4me3-binding pocket (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, RAG2PHD lacks the canonical “aromatic cage” often employed to bind trimethylated lysine residues15 (Figs. 2b and 2c). Instead of being closed on both sides, the back, and the top (as observed with other PHD fingers12-14) the RAG2PHD K4me3-binding surface is open on the top, and resembles an “aromatic channel” rather than an “aromatic cage” (Figs. 2b and 2c). This “channel” conformation may provide a mechanism to modulate histone binding16. Aside from the K4me3 and Q5 residues, the remaining side chains of H3 form no specific interactions with RAG2PHD. Finally, unlike other H3K4me3-binding PHD fingers9,12-14,17, RAG2PHD does not have acidic residues (Asp or Glu) positioned to electrostatically interact with H3R2 (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2. Molecular Basis of H3K4me3-recognition by RAG2PHD.

a, b, 1.15 Å crystal structure of RAG2414-487 complexed with H3K4me3 peptide. a, Ribbon diagram of the complex. For clarity, only the central portion of RAG2414-487 is shown (silver). Residues whose side chains interact with the H3 peptide are shown in green sticks with blue (nitrogen) and red (oxygen) highlights. Residues whose main chain atoms interact with the peptide are labeled in green. The peptide is shown in yellow. With the exception of R2, the side chains of A1 to T6 all interact with RAG2 and are shown in stick models. Zn2+ ions are shown as orange spheres and water molecules mediating protein-peptide interactions are shown as red spheres. Grey dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds. RAG2PHD consists of two unorthodox, interdigitated zinc fingers, linked by a pair of anti-parallel β-strands and a central α-helix. The backbone of the first four residues of the histone H3 peptide are hydrogen bonded with one of the β-strands of RAG2PHD, forming a 3-stranded antiparallel β-sheet. b, The H3 peptide binding surface is conserved among RAG2 proteins. Residues of RAG2 that are conserved through evolution (see Fig. S5) are colored blue on the molecular surface. c, Structural comparison of the PHD fingers from RAG2, BPTF, Yng1 and ING2. Side chains in the PHD fingers that interact with H3K4me3 and H3R2 are highlighted with molecular surface.

The three residues in RAG2 that form the aromatic channel critical for trimethyl-lysine recognition are completely conserved through evolution (Fig. S8). As expected, mutating any one of these residues (Y415A, M443A, W453A/R) abrogated H3K4me3-binding by RAG2PHD (Fig. 3a) and by full-length RAG2 (Fig. 3b). Since the W453R mutation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Omenn's Syndrome18 – a rare severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)19 – and the molecular mechanism linking this mutation to Omenn's Syndrome remains unknown7, we further characterized W453R's role in histone binding. Consistent with the critical role of this residue in forming the recognition surface for H3K4me3, introducing this mutation into the RAG2 PHD finger (RAG2PHD-W453R) abolished the ability of RAG2PHD to bind either full-length histone H3 (Fig. 3c) or intact nucleosomes (Fig. 3d). Thus, the interaction of RAG2 with histone proteins in vitro is dependent upon H3K4me3-binding. We note that RAG2PHD-W453R is properly folded, as indicated by a comparison of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of RAG2PHD and RAG2PHD-W453R (Fig. S9). In addition, the Y415A and M443A substitutions had no effect on PtdInsP-binding by RAG2PHD (Fig. S10), and W453R-associated recombination defects were previously demonstrated to be independent of the PtdInsP-binding activity of RAG27. Thus, the identification of multiple different point mutations that selectively abrogate RAG2's recognition of H3K4me3 allowed us to study the functional significance of this interaction.

Fig. 3. Recognition of H3K4me3 by RAG2PHD is dispensable for RAG2 in vitro enzymatic activity, but essential for RAG2 binding to native histones.

a, Identification of RAG2 PHD finger mutations that specifically disrupt H3K4me3-recognition. Western blot analysis of histone peptide pull-downs with the indicated GST fusion proteins and biotinylated peptides. b, RAG2PHD mutations specifically disrupt binding of full-length RAG2 to H3K4me3. Western blot analysis of histone peptide pull-downs with wild-type and mutant full-length RAG2 proteins and the indicated biotinylated histone peptides. c, The interaction of RAG2 with histone H3 is dependent upon H3K4me3-binding. Western analysis of GST-RAG2PHD, GST-RAG2PHD-W453R, and GST control pull-downs from calf thymus histones. d, The interaction of RAG2 with native nucleosomes requires H3K4me3-binding activity. Nucleosome-binding assays as in Figure 1f with wild-type (RAG2PHD) and mutant (RAG2PHD-W453R) GST-fusion proteins. e, Wild-type and mutant RAG2 proteins express and purify equally well. Anti-FLAG Western analysis of the indicated FLAG-tagged full-length RAG2 proteins purified from 293T cells. f, Mutant RAG2 proteins catalyze wild-type V(D)J cleavage in vitro. The indicated recombinant proteins were tested for in vitro V(D)J cleavage activity. The positions of the substrate (S) and cleavage products (hairpin (H) and nick (N)) are indicated.

Before analyzing the effect of H3 methylation on V(D)J recombination in vivo, we first wanted to confirm that RAG2Y415A, RAG2M443A, and RAG2W453R disrupt H3K4me3-binding without affecting protein folding or the inherent catalytic properties of RAG2. We tested the ability of recombinant wild-type and mutant RAG2 proteins to catalyze V(D)J cleavage in vitro on a naked DNA substrate. In these assays, the recombinant proteins, which all expressed and purified equally well (Fig. 3e), were incubated with core RAG1 (aa 384−1008), and a DNA substrate. All three H3K4me3-binding mutants catalyzed V(D)J cleavage at wild-type levels (Fig. 3f). Therefore, the H3K4me3-binding mutants – RAG2Y415A, RAG2M443A, and RAG2W453R – are properly folded and catalytically active and thus, can be utilized for in vivo functional analyses.

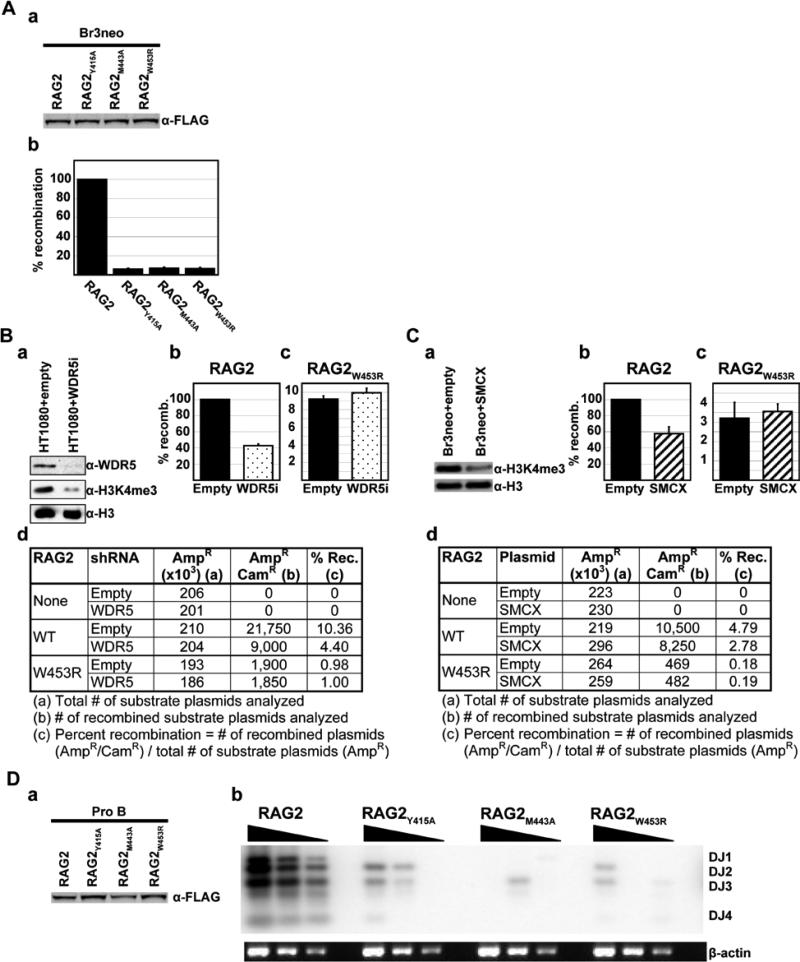

Next, to address whether the recognition of methylated H3 by RAG2PHD plays a role in regulating RAG2 function in vivo, we performed extrachromosomal V(D)J recombination assays with the H3K4me3-binding mutants. Fibroblast cell lines were transfected with an exogenous recombination substrate that becomes partially chromatinized when introduced into cells and has nucleosomes positioned over the recombination signal sequences20, along with full-length RAG1, and either full-length wild-type RAG2, RAG2Y415A, RAG2M443A, or RAG2W453R. Strikingly, despite being expressed at comparable levels to wild-type RAG2 (Fig. 4A-panel a), all three H3K4me3-binding mutants exhibited a profound decrease (>90%) in recombination activity (Fig. 4A-panel b). Thus, the H3K4me3-recognition activity of RAG2 is required for V(D)J recombination in vivo.

Fig. 4. Recognition of H3K4me3 is crucial for RAG1/2 recombinase activity in vivo.

A, The H3K4me3-recognition activity of RAG2 is required for extrachromosomal V(D)J recombination in vivo. (a) Western analysis of FLAG-tagged full-length RAG2 proteins expressed in Br3neo human fibroblast cells confirms that wild-type and mutant RAG2 proteins are expressed at comparable levels in vivo. (b) The indicated constructs were used for transient V(D)J recombination assays in Br3neo cells. Recombination activity was normalized to wild-type activity (RAG2), which was defined as 100%. Wild-type RAG2 consistently gave recombination frequencies of ~5-6%. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of six independent experiments. B, Reducing H3K4 methylation levels specifically impairs V(D)J recombination by wildtype RAG2. (a) Western analysis demonstrates that the WDR5 shRNA vector reduces H3K4me3 levels. (b-c) Transient V(D)J recombination assays performed with wild-type (b) or mutant (c) RAG2 in HT1080 human fibroblast cells in the presence (stippled) or absence (filled) of a WDR5 shRNA vector. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of six independent experiments. (d) Representative recombination data. C, Reducing H3K4me3 levels by demethylation specifically reduces V(D)J recombination by wildtype RAG2. (a) Western analysis confirms that SMCX expression reduces H3K4me3 levels. (b-c) Transient V(D)J recombination assays were performed with wild-type (b) or mutant (c) RAG2 in Br3neo cells in the presence (hatched) or absence (filled) of SMCX. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of six independent experiments. (d) Representative recombination data. D, The H3K4me3-recognition activity of RAG2 is required for chromosomal V(D)J recombination at the endogenous murine IgH locus. (a) Western analysis of FLAG-tagged full-length RAG2 proteins expressed in lentivirally transduced RAG2-/- Pro-B cells confirms that wild-type and mutant RAG2 proteins are expressed at comparable levels in vivo. (b) Endogenous V(D)J recombination assays in Pro-B cells transduced as in (a). Southern blot analysis of PCR-amplified genomic DNA on an agarose gel. Serial dilutions represent PCR-amplification of 400, 200, and 100 ng of genomic DNA. Results shown are representative of four independent experiments.

To directly test the importance of H3K4 methylation and the interaction between RAG2 and H3K4me3 for V(D)J recombination in vivo, we used two different methods to reduce endogenous H3K4 methylation levels, and then repeated the extrachromosomal V(D)J recombination assays. First, H3K4 methylation levels were reduced (Fig. 4B-panel a) by knocking down expression of the common histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase component WDR515,21 with shRNA. Consistent with the decreased recombination observed with the H3K4me3-binding mutants, we observed a marked reduction in the recombination activity of wildtype RAG2 (~60%) in cells carrying the WDR5 shRNA (Fig. 4B-panels b, d). Significantly, V(D)J recombination by RAG2W453R – which does not recognize H3K4me3 – was unaffected by the presence of WDR5 shRNA (Fig. 4B-panels c, d), indicating that the reduction observed for wildtype RAG2 is specifically due to reduced H3K4me3-binding. In a second independent method, we reduced H3K4me3 levels by transiently expressing the H3K4me3 demethylase SMCX22. As with WDR5 shRNA, we observed that decreases in H3K4me3 levels (Fig. 4C-panel a) resulted in a significant reduction in recombination (~45%) in cells expressing SMCX (Fig. 4C-panels b, d). V(D)J recombination by RAG2W453R was unaffected by SMCX expression (Fig. 4C-panels c, d). Thus, reducing either the levels of H3K4 methylation or the ability of RAG2 to bind H3K4me3, impairs V(D)J recombination.

Since H3K4me3 is observed at actively rearranging gene segments23 (Fig. S12), we assayed the ability of the H3K4me3-binding mutants to perform chromosomal V(D)J recombination at the endogenous murine IgH locus. RAG2-/- Pro-B cells were transduced with lentiviruses encoding either RAG2, RAG2Y415A, RAG2M443A, or RAG2W453R and the extent of DH-to-JH recombination in the transduced cell populations was measured using a standard semi-quantitative PCR strategy. Despite being expressed at comparable levels to wild-type RAG2 (Fig. 4D-panel a), all three H3K4me3-binding mutants exhibited a dramatic reduction in DH-to-JH recombination (Fig. 4D-panel b). Thus, we conclude that recognition of H3K4me3 by RAG2PHD is crucial for V(D)J recombination at the endogenous immunoglobulin locus.

Our findings provide the first direct molecular link between histone methylation and mammalian DNA recombination. Prior to this study, H3K4me3 had only been demonstrated to function in the regulation of gene expression15. Our results, demonstrating a novel function for this mark in V(D)J recombination, highlight that chromatin structure can be coupled to diverse nuclear processes via protein modules that recognize modified histones. We have also provided the first evidence that disrupting the read-out of histone modifications can cause an inherited human disease. Omenn's Syndrome has been observed in patients carrying a W453R mutation in RAG218. Since RAG2W453R exhibits wildtype enzymatic activity in vitro7 (Fig. 3f), it has been unclear how this mutation causes immunodeficiency. Here, we have shown that the W453R mutation disrupts the read-out of H3K4me3, thereby providing a molecular explanation of how RAG2W453R causes Omenn's Syndrome. While the W453R, M443A, and Y415A point mutations – which selectively disrupt H3K4me3-recognition – severely disrupt V(D)J recombination, complete deletion of the RAG2 C-terminus (including the PHD finger) only partially compromises V(D)J recombination activity24-27 (Fig S11). We propose that the RAG2-H3K4me3 interaction serves two functions: (1) increases the stable association of RAG1/2 complexes at target sites and (2) might relieve an inhibitory activity present in the C-terminal portion of RAG27 (Fig S13). Taken together with other studies that have demonstrated a link between the writing of histone modifications and human disease15,28,29, our results highlight the fundamental role chromatin plays in human health. We postulate that in the coming years other naturally occurring mutations that cause inherited human diseases will be linked to disruption of lysine methylation signaling pathways.

Methods Summary

Biotinylated peptides were synthesized at Stanford or Yale Protein and Nucleic Acid facilities. Peptide microarray experiments were performed essentially as described17. Biotinylated peptide pull-down assays, calf thymus histone binding assays, and mononucleosome gel shift assays were performed as described9. Tryptophan fluorescence assays were performed essentially as described13. NMR structure determination was performed as described7. The structure determination is described in Methods. In vitro V(D)J cleavage assays were performed as described31. The extrachromsomal V(D)J recombination assays and the endogenous V(D)J recombination assay are described in Methods. Information about antibodies is available in Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Karim-Jean Armache and Ji-Joon Song for the generous gift of recombinant mononucleosomes; Robert Kingston and members of the Kingston lab for helpful discussions; and Nelson Lau, Ji-Joon Song, and Martin Gellert for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants to M.A.O., O.G., D.I., and T.G.K. as well as a Korea Research Foundation grant to S.H. O.G. is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Career Award in Biomedical Sciences and a Kimmel Scholar Award. S.R.-M. has been the recipient of a fellowship from the Human Frontier Science Program. A.J.K. is funded by Stanford University through a Genentech Foundation Predoctoral Fellowship. A.G.W.M. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Predoctoral Fellow.

Methods

Materials and plasmids

Antibodies used in the study: Histone H3 (Abcam); Flag M5 (Sigma); Flag M2 (Sigma); GST (Santa Cruz); donkey anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked F(ab')2 fragment (GE Healthcare); sheep anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked whole Ab (GE Healthcare); and Alexa Fluor 647 chicken anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen). GST-RAG2PHD (aa 414-487), GST-RAG2PHD (aa 414-527), and FLAG-tagged RAG2 were described previously7. Point mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis PCR using Pfu turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The GST-PHD finger of hING2 (aa 200-281) was described previously9.

Peptide microarray

Peptide microarray experiments were performed as described previously17. Briefly, biotinylated histone peptides were printed in 6 replicates onto a streptavidin-coated slide (ArrayIt) using a VersArray Compact Microarrayer (Bio-Rad). After a short blocking incubation with biotin (Sigma), the slides were incubated with GST-fused RAG2PHD in peptide binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 20% fetal bovine serum) overnight at 4 °C with gentle agitation. After washing with the same buffer, slides were probed first with anti-GST antibody and then fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized with GenePix 4000 scanner (Molecular Devices).

Biotinylated peptide binding assays

Biotinylated peptide pull-down assays were performed as described previously9. Briefly, 1μg of biotinylated peptides were incubated with 1 μg of GST-PHD fingers in peptide binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40) overnight at 4°C. After 1h incubation with streptavidin beads (Amersham), complexes were washed 3 times with the binding buffer, and the bound proteins were subjected to either Western or Coomassie analysis.

Calf thymus histone binding assays

Calf thymus histone binding assays were performed as described previously9. Briefly, 10 μg of GST-RAG2PHD was incubated with 25 μg of calf thymus histones (Worthington) in binding buffer (50mM Tris-Hcl 7.5, 1M NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40) overnight at 4°C. After being incubated with glutathione beads for 1h, complexes were washed 3 times with binding buffer, and bound proteins were subjected to Western analysis.

Mononucleosome shift assay

Mononucleosome gel shift assays were performed as described previously9. Briefly, 1.5 μg of mononucleosomes isolated from HeLa cells or assembled from recombinant histones32 were incubated with GST-RAG2PHD in binding buffer (20mM HEPES 7.9, 80mM KCl, 0.1mM, ZnCl2, 0.1% EDTA and 10% glycerol) at 30°C for 30 minutes. The reaction was then subjected to 5% TBE native gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium-bromide staining.

Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy

The fluorescence spectra were recorded at 25°C on Fluoromax3 spectrofluorometer. The samples of 10 μM RAG2PHD containing progressively increasing concentrations (up to 2 mM) of histone H3 peptides (aa 1-12) were excited at 295 nm. Emission spectra were recorded between 305 and 405 nm with a 0.5 nm step size and a 1 s integration time and averaged over 3 scans. The Kd's were determined by a nonlinear least-squares analysis using the equation: ΔI=(ΔImax*L)/(KD+L), where L is concentration of the histone peptide, ΔI is observed change of signal intensity, and ΔImax is the difference in signal intensity of the free and bound states of the RAG2 PHD finger. The Kd value was averaged over two experiments for the H3K4me3 binding and over three separate experiments for the binding of H3K4me0, H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 peptides.

Data collection and structure determination

The RAG2 PHD finger (residues 414-487) was prepared as described16. Crystals of its complex with H3K4me3 were obtained at 3 mg/ml protein concentration and 1:1.5 molar ratio of protein to peptide with a precipitant solution of 26 % PEG 3350 and 0.18 M potassium thiocyanate. X-ray diffraction data were collected from a single crystal of RAG2-PHD - H3K4me3 complex on a Mar225 CCD detector at ID-22 1 Å beamline in Advanced Photon Source (APS) at -160°C. The crystal belongs to the C2 space group with 2 RAG2-PHD-H3K4me3 complexes per asymmetric unit (Table S1). Ramachandran statistics: 93.3% allowed region, 6.7% additionally allowed region. The data set was processed and scaled at 1.15 Å using HKL200033. Crystallographic phases were obtained by molecular replacement with PHASER34, using as a model the 2.4 Å resolution structure of RAG2-PHD-H3K4me3 determined previously35. The model was traced using COOT36 and refined using CNS37 and SHELX38. Individual anisotropic displacement parameters were refined for all atoms, and hydrogens were added in the late stages of refinement.

In vitro V(D)J cleavage assays

FLAG-tagged RAG2 and derivatives were used for in vitro V(D)J cleavage assays as described previously39. Briefly, V(D)J cleavage assays were initiated by the addition of R1 (~80 ng) and R2 (~10 ng) proteins to a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 0.25 pmol of 32P-labeled, uncleaved 12-RSS substrate (VDJ100/101) in 60 mM KGlu, 1 mM MnCl2, 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), and 2mM DTT. After a 2-hr incubation at 30°C, the reactions were stopped by addition of 95% formamide loading dye. The samples were denatured by heating at 95°C for 5 minutes and reaction products were visualized by autoradiography of samples separated by denaturing electrophoresis.

Extrachromosomal V(D)J recombination assays

Extrachromosomal V(D)J recombination assays were performed as described previously40 in either Br3neo40 or HT10809 human fibroblastoid cells, and the plasmid pGG49 was used as the reporter41. Full-length RAG1 was transiently expressed using the pcDNA6-myc-hisA vector (Invitrogen). RAG2 and derivatives were transiently expressed using the p3xFLAG-CMV vector (Sigma). Expression of all proteins was confirmed by Western analysis. For the WDR5 shRNA experiments, HT1080 cells were first stably transfected with either a WDR5 shRNA vector or a control vector that lacks the shRNA insert. These cells were subsequently transfected with RAG1, RAG2, and a recombination substrate. Activity was normalized to that of wild-type RAG2 in the absence of WDR5, which was defined as 100%. For the SMCX experiments, Br3neo cells were simultaneously co-transfected with RAG1, RAG2, a recombination substrate, and either an SMCX mammalian expression vector, or a control vector that lacks the SMCX insert. Activity was normalized to that of wild-type RAG2 in the absence of SMCX, which was defined as 100%.

Endogenous V(D)J recombination assays

Endogenous V(D)J recombination assays were performed essentially as described previously26,42, except that RAG2-/- Pro B cells were lentivirally transduced with RAG2 and derivatives. Expression of all proteins was confirmed by Western analysis.

Footnotes

Note added in proof: While this work was under review, another study also reported that the RAG2 PHD finger binds to methylated H3K430.

Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the RAG2PHD-H3K4me3 peptide complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession code of 2v89. Reprints and permissions information is available at npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Gellert M. V(D)J recombination: RAG proteins, repair factors, and regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:101–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.150203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oettinger MA. How to keep V(D)J recombination under control. Immunol Rev. 2004;200:165–81. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhury D, Sen R. Stepwise activation of the immunoglobulin mu heavy chain gene locus. Embo J. 2001;20:6394–403. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson K, Angelin-Duclos C, Park S, Calame KL. Changes in histone acetylation are associated with differences in accessibility of V(H) gene segments to V-DJ recombination during B-cell ontogeny and development. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2438–50. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2438-2450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morshead KB, Ciccone DN, Taverna SD, Allis CD, Oettinger MA. Antigen receptor loci poised for V(D)J rearrangement are broadly associated with BRG1 and flanked by peaks of histone H3 dimethylated at lysine 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11577–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932643100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callebaut I, Mornon JP. The V(D)J recombination activating protein RAG2 consists of a six-bladed propeller and a PHD fingerlike domain, as revealed by sequence analysis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:880–91. doi: 10.1007/s000180050216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkin SK, et al. A PHD finger motif in the C terminus of RAG2 modulates recombination activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28701–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragvin A, et al. Nucleosome binding by the bromodomain and PHD finger of the transcriptional cofactor p300. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:773–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi X, et al. ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature. 2006;442:96–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wysocka J, et al. A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature. 2006;442:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature04815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West KL, et al. A direct interaction between the RAG2 C terminus and the core histones is required for efficient V(D)J recombination. Immunity. 2005;23:203–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, et al. Molecular basis for site-specific read-out of histone H3K4me3 by the BPTF PHD finger of NURF. Nature. 2006;442:91–5. doi: 10.1038/nature04802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pena PV, et al. Molecular mechanism of histone H3K4me3 recognition by plant homeodomain of ING2. Nature. 2006;442:100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature04814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taverna SD, et al. Yng1 PHD finger binding to H3 trimethylated at K4 promotes NuA3 HAT activity at K14 of H3 and transcription at a subset of targeted ORFs. Mol Cell. 2006;24:785–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramon-Maiques S, et al. The PHD finger of RAG2 recognizes histone H3 methylated at both lysine-4 and arginine-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709170104. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi X, et al. Proteome-wide analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies several PHD fingers as novel direct and selective binding modules of histone H3 methylated at either lysine 4 or lysine 36. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2450–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600286200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez CA, et al. Mutations in conserved regions of the predicted RAG2 kelch repeats block initiation of V(D)J recombination and result in primary immunodeficiencies. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5653–64. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5653-5664.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villa A, et al. Partial V(D)J recombination activity leads to Omenn syndrome. Cell. 1998;93:885–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumann M, Mamais A, McBlane F, Xiao H, Boyes J. Regulation of V(D)J recombination by nucleosome positioning at recombination signal sequences. Embo J. 2003;22:5197–207. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims RJ, 3rd, Reinberg D. Histone H3 Lys 4 methylation: caught in a bind? Genes Dev. 2006;20:2779–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.1468206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwase S, et al. The X-linked mental retardation gene SMCX/JARID1C defines a family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. Cell. 2007;128:1077–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkins EJ, Kee BL, Ramsden DA. Histone 3 lysine 4 methylation during the pre-B to immature B-cell transition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1942–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akamatsu Y, et al. Deletion of the RAG2 C terminus leads to impaired lymphoid development in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1209–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237043100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corneo B, et al. Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature. 2007;449:483–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirch SA, Rathbun GA, Oettinger MA. Dual role of RAG2 in V(D)J recombination: catalysis and regulation of ordered Ig gene assembly. Embo J. 1998;17:4881–6. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang HE, et al. The “dispensable” portion of RAG2 is necessary for efficient V-to-DJ rearrangement during B and T cell development. Immunity. 2002;17:639–51. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00448-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Y, Whetstine JR. Dynamic regulation of histone lysine methylation by demethylases. Mol Cell. 2007;25:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tenney K, Shilatifard A. A COMPASS in the voyage of defining the role of trithorax/MLL-containing complexes: linking leukemogensis to covalent modifications of chromatin. J Cell Biochem. 2005;95:429–36. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Subrahmanyam R, Chakraborty T, Sen R, Desiderio S. A Plant Homeodomain in Rag-2 that Binds Hypermethylated Lysine 4 of Histone H3 Is Necessary for Efficient Antigen-Receptor-Gene Rearrangement. Immunity. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews AG, Elkin SK, Oettinger MA. Ordered DNA release and target capture in RAG transposition. Embo J. 2004;23:1198–206. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–60. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minor ZOAW. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collection in oscillation mode. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramon-Maiques S, et al. The PHD finger of RAG2 recognizes histone H3 methylated at both lysine-4 and arginine-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709170104. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheldrick GM, Schneider TR. SHELXL: High-resolution refinement. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:319–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elkin SK, Matthews AG, Oettinger MA. The C-terminal portion of RAG2 protects against transposition in vitro. Embo J. 2003;22:1931–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dai Y, et al. Nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination require an additional factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2462–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437964100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gauss GH, Lieber MR. Unequal signal and coding joint formation in human V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3900–6. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlissel MS, Corcoran LM, Baltimore D. Virus-transformed pre-B cells show ordered activation but not inactivation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and transcription. J Exp Med. 1991;173:711–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.