Abstract

Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, is a proven biological weapon. In order to study this threat, a number of experimental surrogates have been used over the past 70 years. However, not all surrogates are appropriate for B. anthracis, especially when investigating transport, fate and survival. Although B. atrophaeus has been widely used as a B. anthracis surrogate, the two species do not always behave identically in transport and survival models. Therefore, we devised a scheme to identify a more appropriate surrogate for B. anthracis. Our selection criteria included risk of use (pathogenicity), phylogenetic relationship, morphology and comparative survivability when challenged with biocides. Although our knowledge of certain parameters remains incomplete, especially with regards to comparisons of spore longevity under natural conditions, we found that B. thuringiensis provided the best overall fit as a non-pathogenic surrogate for B. anthracis. Thus, we suggest focusing on this surrogate in future experiments of spore fate and transport modelling.

Background

Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, has received much attention in the past decade due to its use in 2001 as a biological weapon distributed through the USA mail system. However, B. anthracis spores have been used as a weapon for close to 100 years and, historically, this pathogen was an important disease model [1]. This bacterium also provides a nearly perfect model of prokaryotic clonal evolution, with rare genomic recombination and extremely low levels of homoplasy [2]. The body of research acquired for B. anthracis provides key insights into its biology, epidemiology and the risks associated with its release into a civilian environment [3]. However, an important gap still remains in our empirical understanding of B. anthracis spore survival and mobility. As a result, it is necessary to examine and develop more accurate fate and transport models of anthrax spores in order to better understand public health risks and develop methods for emergency response to a mass release.

Mathematical fate and transport models provide a means of predicting the distribution of pathogenic particles after their release into air or water. Clearly, such information is an important asset in risk assessment following a terrorist attack or a biological accident. Scenarios for intentional release into a civilian area include infecting the water supply or releasing aerosolized spores [4,5]. In a 1970 report, the World Health Organization predicted that 50 kg of spores released upwind of 500,000 civilians would result in 95,000 fatalities; likewise, a single subway attack could lead to over 10,000 deaths if carried out during rush hour [6]. Model scenarios and the 2001 events demonstrate that non-targeted individuals are also vulnerable. However, models may lack predictive power if their critical parameters are not based on real world values. Therefore, it is necessary to collect experimental data that will lead to greater model accuracy of spore behaviour. For example, our laboratory group is performing experiments to measure attenuation values for spore survivability in natural and artificial environments (such as water, soil and fomites). These and other experiments will help to validate the predictions of current mathematical models, thereby increasing model accuracy and improving our response to natural, accidental or intentional releases of anthrax.

Fully virulent B. anthracis must be handled under biosafety level (BSL)-3 conditions and requires secure containment. Therefore, we cannot experimentally release this organism into the environment nor use it in experiments outside of a BSL3 facility. In order to conduct experiments that inform release models, we must use a non-pathogenic bacterium that can accurately represent B. anthracis. Surrogates of this type have been used for many years in military release experiments, water supply studies and food protection assessment. However, little attention has been focused on the criteria used to select surrogates. Our synthesis makes use of existing empirical evidence to present an informed decision for the best choice of a B. anthracis surrogate.

History of surrogate use for B. anthracis

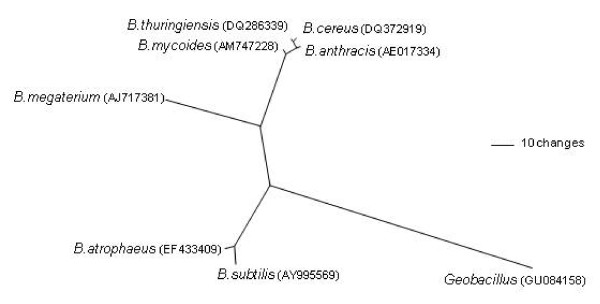

Before selecting an appropriate surrogate for B. anthracis, it is useful to review the history of surrogate use for this organism. This information, though anecdotal in some cases, provides valuable information useful for surrogate selection such as (1) comparative survival and behavioural data, (2) an initial list of potential surrogate candidates and (3) baseline data to compare against current experiments. Over the years a number of surrogates have been used, including an attenuated B. anthracis strain (Sterne) and several phylogenetic relatives: B. atrophaeus (formerly B. globigii and B. subtilis niger [7,8]), B. cereus, B. megaterium, B. mycoides, B. subtilis, B. thuringiensis and Geobacillus (Figure 1). Table 1 indicates the number of times each has been utilized in published studies. B. atrophaeus has been employed most frequently; B. cereus, B. subtilis and B. thuringiensis have been used moderately; and the others have been used just a few times (B. megaterium, B. mycoides and Geobacillus).

Figure 1.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree of Bacillus anthracis and potential near-neighbour surrogates. Reconstruction is based on neighbour-joining analysis of 16 s rRNA gene sequences using Jukes-Cantor correction. GenBank accession numbers are provided in parentheses.

Table 1.

Number of historical uses for each potential surrogate with references.

| Species* | No. of uses† | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus atrophaeus | 40 | [15,17,18,27,29,34,40-42,48,50,52,54,68,71,72,75,76,78,83,86-88,94,95,101,102,104,107,109,112-115,174,208,219-222] |

| B. cereus | 29 | [22,26,40-43,48,54,58,59,65,66,68-70,72,73,77,82,88,95,103,104,174,213,223-226] |

| B. subtilis | 26 | [19,37,40,42-44,48,60,70,82,84,85,88,94,96,100,104-106,174,209,213,216,219,224,226] |

| B. thuringiensis | 26 | [16,22,26,27,40-43,48,58,60,66,68,72,81,82,88,94,95,99,100,111,174,192,227,228] |

| B. anthracis Sterne | 20 | [25,26,40,43,48,49,58-60,68,72,75,81,103,174,213,223,224,226,229] |

| B. megaterium | 8 | [40-42,48,94,102,104,174] |

| B. mycoides | 4 | [43,60,72,226] |

| Geobacillus | 3 | [37,174,209] |

*Strains not identified.

†References through January 2010.

Both the USA and Japanese governments used pathogenic simulants in biological warfare test studies. For example, Yoshi Iishi of Japan confessed after World War II to using B. anthracis surrogates in his biological warfare programme, which was initiated in 1935 [9]. The USA began using B. atrophaeus as their major non-pathogenic surrogate for B. anthracis in July of 1943 at Camp Detrick [9]. This surrogate has been used for many experiments in order to ascertain potential outcomes of using anthrax as a biological weapon [10-12]. In 1949 the USA Army experimentally sprayed B. atrophaeus and Serratia marcescens over the coastal population centers of Hampton, Virginia and San Francisco, California [9]. B. atrophaeus was also disseminated in Greyhound bus and New York subway terminals via covert spray generators hidden in briefcases during the mid-1960 s [11]. More recent work at national laboratories has emphasized the detection and identification of spores in the environment.

The earliest in-depth comparison of related Bacillus species was done by Schneiter and Kolb [13,14], who tested heat processing methods to destroy 'industrial' spores of B. anthracis, B. subtilis and B. cereus found on shaving brush bristles. Brazis et al. [15] made a direct comparison of the effect of free available chlorine on B. anthracis and B. atrophaeus spores and found that B. atrophaeus was more resistant to chlorine. In these early works, no mention is made of the potential for these species to be used as B. anthracis surrogates. However, their results provide valuable comparative data (for example, B. atrophaeus is more resistant to chlorine and therefore is a conservative surrogate for estimating B. anthracis survival in tap water).

More recent experiments have examined the effects of various environmental challenges and disinfectants on B. anthracis surrogates, including studies of food protection or decontamination in the wake of a release event. Faille et al. [16] used B. thuringiensis as a non-pathogenic representative for B. cereus and indicated that B. thuringiensis has been used in this capacity for many years. Others have used B. atrophaeus, B. thuringiensis, B. cereus and B. subtilis to examine decontamination strategies using various bactericidal compounds such as chlorine, hydrogen peroxide, dyes, neutral oxone chloride, formaldehyde, gluteraldehyde and antibiotics [15,17-43]. Additional decontamination methods used against these surrogates include ultraviolet irradiation [39,44-50], plasma [51], electron beam radiation [52,53] and heat [39,54-63].

B. anthracis stand-ins have also played an important role in evaluating the broad arsenal of techniques used to detect and identify bio-threat agents in the environment. At least 17 methods have been employed to detect spores of B. anthracis and its relatives, including: electron microscopy [64], atomic force microscopy [65-68], photothermal spectroscopy [69], microcalorimetric spectroscopy [70], biochip sensors [71,72], Raman spectroscopy [73], polymerase chain reaction methods [74-80], optical chromatography [81], differential mobility spectroscopy [82], laser induced breakdown spectroscopy [83-86], flow cytometry sorting [87], mass spectroscopy [88-96], proteomics [97,98], luminescence analysis [99], long-wave biosensors [100], lytropic liquid sensors [101] and fluorescent labelling [102-105]. Although most of these studies used B. anthracis directly, some included close relatives for comparisons of detectability across species.

Lastly, surrogates have played an important role in several types of aerosol studies. They have been used to evaluate electrical forces [106,107], examine the effect of filter material on bioaerosol collection [108] and to determine if bees could be deployed to detect anthrax spores in the air [109]. Other studies have used stand-ins such as B. thuringiensis to test spore movement in aerial spray [4,110,111], transport and deposition efficiency of spores in ventilation ducts [112], engineered aerosol production [113] and re-aerosolization of spores [114]. B. atrophaeus has been used to reproduce an anthrax letter event, demonstrating how an individual swine located 1.5 m from an opened letter inhaled >21,000 spores [115]. This is a lethal dose for humans exposed to B. anthracis and validates the significant biothreat of passive spore dispersion.

From the diverse experimental uses of anthrax surrogates during the last 70 years, it is obvious that non-pathogenic representatives are indispensable for conducting safe inquiries into the behaviour and mobility of pathogen spores. However, not all species are equally appropriate stand-ins for B. anthracis. In the remainder of this review we outline our selection criteria, present pertinent literature for surrogate selection in B. anthracis and identify gaps in our knowledge of a surrogate's ability to mimic the behaviour of this pathogen. Whenever possible, we present quantified values to provide robust justification of any surrogate to be used in future fate and transport experiments.

Selection criteria

We used several criteria for selection, including (1) the risk of use (pathogenicity), (2) genetic similarity to B. anthracis, (3) morphology and (4) response to various chemical and environmental challenges. Our initial list began with microbes in the family Bacillaceae that have been used as surrogates in the past. Practical attributes of potential surrogates are summarized in Table 2. It is important to select appropriate representatives with regard to the specific experiments one wishes to conduct. As an example, if we were interested in studying the disinfectant capacity of a substance we would use a surrogate that has greater survivability than our target organism. The results would then provide conservative estimates of appropriate disinfectant levels. In our case, we are interested in physical experiments of mobility in water and air media. Hence, we determined that the physical properties of the spores are of greatest interest, including size, shape, density, surface morphology, surface structure and surface hydrophobicity. Behavioural responses to stress and natural conditions are also relevant to spore survival.

Table 2.

Practical attributes in surrogate selection

| Attribute | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Safety | Should not cause illness or infection in animals or plants |

| Ease of culture | Able to produce with standard microbiological methods in a reasonable timeframe and have reproducibility |

| History of use | Possibility of attaining comparative information from the literature and judging surrogate behaviour |

| Ease and speed of detection | Allows large numbers of samples to be processed for rapid feedback of results |

| Cost | Surrogate production and detection should not be excessive |

| Stability or persistence | No long-term persistence, or easily decontaminated |

| Practical for industrial testing | Should not damage equipment or processes |

Surrogate pathogenicity

The risks associated with surrogate use are of critical concern. Table 3 lists the biosafety designations for the potential surrogates. Surrogates are typically used to replace a pathogen that, if used, would present a potential threat to public health. B. anthracis is classified as a BSL-3 organism and work must be conducted under highly contained conditions not suitable for fate and transport experiments. Ideally, an attenuated strain of B. anthracis would be a good surrogate because it should behave similarly to the pathogenic strains and pose little risk. However, our knowledge of plasmid exchange rates and the environmental effects of these strains remains very limited - they may still pose a risk despite being classified as BSL-2 organisms. In addition, detection of B. anthracis in the environment, even of an attenuated strain, could cause a public relations issue. Worse, released surrogates might mask a real attack or create high background positives and unnecessary emergency responses. Therefore, we feel that non-pathogenic B. anthracis strains are not good surrogates for fate and transport experiments.

Table 3.

Biosafety levels for the potential Bacillus anthracis surrogates (from the Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository)

| Species | Biosafety laboratory rating |

|---|---|

| Bacillus anthracis Ames | BSL 3 |

| B. anthracis Sterne | BSL-2 |

| B. cereus | BSL-2 |

| B. megaterium | BSL-2 |

| B. atrophaeus | BSL-1 |

| B. subtilis | BSL-1 |

| B. thuringiensis | BSL-1 |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus | BSL-2 |

BSL, biosafety level.

Another surrogate of interest is B. cereus. This species is an opportunistic food-borne pathogen that can infect humans [116,117] and the CDC recommends the handling of the organism at BSL-2 standards. Although it is naturally found in the environment, additional releases of this potential pathogen are deemed unsafe. As such, this organism cannot be used as a replacement for B. anthracis in spore release studies. The same is true for B. megaterium and Geobacillus stearothermophilus, which are treated as BSL-2 organisms.

The other potential surrogates, including B. atrophaeus, B. mycoides, B. subtilis and B. thuringiensis, are not typically regarded as potential human pathogens or select agents. They are BSL-1 organisms and are safe candidates. B. thuringiensis is used as an insecticide throughout the world, and has been shown to pose no health risk to humans in some studies [118,119]. Infections do occasionally occur, however. These include a case from using commercial B. thuringiensis var. kurstaki [120], a wound infection identified as B. thuringiensis strain 97-27 [74,121], and an isolate recovered from a gastrointestinal illness [122]. That said, the overall the use of most B. thuringiensis strains appears to be safe and this species provides a good potential surrogate for B. anthracis [118,119]. B. atrophaeus is commonly found in soil throughout the world, is considered non-pathogenic and has been used extensively as a surrogate for B. anthracis [40,123]. B megaterium and B. subtilis are also found in the soil and are non-pathogenic to humans. Based on safety concerns, most candidates except B. cereus could serve as a surrogate for B. anthracis.

Genetics of the potential surrogates

Genetic relationships are important when selecting a surrogate because, theoretically, a phylogenetic relative should be morphologically and behaviorally more similar and have comparable physical characteristics to the target organism. There have been many genetic studies that elucidate the phylogenetic relationships of organisms related to B. anthracis [74,98,124-143]. The results of these studies indicate that B. anthracis is most closely related to B. cereus, B. thuringiensis and B. mycoides, which are grouped together as the B. cereus group (Figure 1). In contrast, B. subtilis, B. atrophaeus, B. megaterium, and Geobacillus are more distant relatives of B. anthracis. As their chromosomal genomes are very similar, some authors have suggested that B. cereus, B. thuringiensis and B. anthracis are actually a single species separated only by different plasmid composition [130]. However, highly informative genetic markers such as single nucleotide polymorphisms can resolve B. anthracis from these near neighbor species [144,145]. The identification of closely related surrogates does not present a problem when these powerful genetic tools are used. The importance of genetic similarity on spore composition is demonstrated by the BclA gene, which is unique to the B. cereus group. This protein is found in the exosporium and helps determine the adhesive properties of the spore [146,147]. As B. atrophaeus and B. megaterium are lacking this gene, we would expect important changes in behavior compared to B. anthracis.

Morphology of the potential surrogates

Morphological characters are important to consider when choosing a surrogate because physical behaviours are the foundation of transport models. As stated earlier, genetic relatedness is a good indicator of morphological similarity, so we expect organisms within the B. cereus group to be morphologically similar to B. anthracis. Microscopy examination reveals few morphological features that can be used to definitively distinguish the various species from one another [64,65,68]. However, spores present measurable differences among surrogates, including the structure of the exosporium, the presence/absence of filamentous appendages and size variation.

The spores of the B. cereus group all possess a specific type of exosporium surrounding the outer spore coat. It is a balloon-like sac that envelopes the spore, is made of crystal lattices and, typically, has a short nap of hair-like projections extending off the surface [64-68,146,148-154]. The exosporium can be highly variable, both among B. anthracis relatives [155-157] and within B. anthracis, as shown by differences between the Vollum and Sterne strains [158]. Some species also have long appendages that extend off the exosporium, known as filaments. B. cereus, B. megaterium and B. thuringiensis all possess filaments, whereas B. anthracis has none [64,149-152,158-161]. More distant relatives such as B. atrophaeus and B. subtilis have neither a nap nor filaments [67,68,152,162]. Likewise, B. atrophaeus and B. megaterium have an atypical exosporium-like layer that is distinct but does not extend off the surface of the outer coat [64,67,148,152,162-165]. B. thuringiensis has a similar nap to B. anthracis but the presence or absence of filaments in B. thuringiensis is variable [152,166-168]. It is important to note that the exosporium is strongly hydrophobic [169] and that this chemical property may influence flow dynamics in aqueous solutions. Therefore, species with less hydrophobic spores (B. subtilis) are probably not appropriate simulants compared to the B. cereus group. As differences in exterior morphology will influence the mobility of pathogen spores in air and water, the investigation of these dynamics is a much-needed focus of future research.

Size, shape and density of the spore are also considered important factors that can influence surrogate behavior in release experiments. The spores of the B. cereus group have similar ratios of length to width and similar diameters, whereas the spores of B. atrophaeus are smaller and those of B. megaterium are larger [65,68,170,171]. Although the difference in size is not great, it does exist and may require different coefficients for various model parameters (such as, Reynolds number, diffusion coefficient and sedimentation velocity) [172,173]. Spore volume is strongly correlated to density (R = 0.95) when spores are wet and in a moistened state the smaller spores of B. atrophaeus and B. subtilis are much more dense than B. anthracis [174]. Such differences are likely to affect the behaviour of these particles in air or water. Wet B. thuringiensis spores have densities and volumes within the range of B. anthracis, making this simulant a better match for the measurement of liquid dispersion. Interestingly, dry spore density is similar among the surrogates listed in Table 1, despite volume differences [174]. Thus, the right choice of surrogate appears to depend on the dispersion medium under consideration.

Comparative survivability among surrogates

Previous experiments comparing the survivability of various spore-formers provide valuable information to the surrogate selection process. Comparative experiments of spore survival under natural conditions or exposure to heat, ultraviolet and chemical disinfectants can illuminate which species may behave similarly to B. anthracis in experiments. In this section we review the literature for comparative spore survival.

Quantitative data relating inactivation kinetics of the natural survival of spores would be of great value when comparing potential surrogates. Unfortunately, most of the available data are qualitative. Past studies with B. anthracis have revealed that spores may survive for years under natural conditions [175-190]. The data are mostly qualitative, not directly comparable, and primarily exist only for B. anthracis. Experimental evidence that quantifies survival rates in both the short and long term are missing. Several studies examined the attenuation rate of B. thuringiensis spores on leaves, soil and snow [191-197]; B. cereus was included in a survival study measuring the effects of soil pH, moisture, nutrients and presence of other microbes [198]. In addition to two aerosol field studies [110,199], we found no other studies that investigated natural attenuation rates of the potential surrogates for B. anthracis or that compared several species at once. Another drawback to using these data is that spore behaviour is variable due to factors such as purification method, sporulation conditions and strain type, and in many of these studies different purification protocols and strains are used, which makes direct comparisons of the values mostly pointless. Nevertheless these values do have some comparative information that can be used for surrogate selection. For example, natural attenuation values have been quantified for B. cereus and B. thuringiensis demonstrating that, after 135 days, the number of viable B. thuringiensis spores falls to about a quarter of the original inoculum [194]. The same may be true for B. anthracis but data are lacking. Although some spores remain active for a long time, the rate at which they lose viability is unknown, which suggests that additional experimental evidence is required to confirm the decay rates for B. anthracis spores and the potential surrogates.

Many experiments have been conducted that examine the effects of heat on spores [39,54,57,63,200-208]. However, very few studies have focused on quantifying differences in the survival of spores with regards to surrogate selection. More recent studies have compared the affect of heat on spores with the intention to understand differences among species. The main focus of most of these experiments is related to industrial sanitation, particularly disinfection in the food industry [58-60,62,209-211]. Montville and coworkers [60] have published the only study that specifically compares attenuation values among several surrogates. Whitney et al. [39] review some of the studies on the thermal survival of B. anthracis, whereas Mitscherlich and March [212] provide a very comprehensive review on the overall survival of B. anthracis and many of the potential surrogate candidates. However, it is apparent that the variability of D values (decimal reduction times) within species is large enough that we cannot make any robust decisions based upon this comparative information [60]. Rather, from these data we realize that each strain may behave differently with regards to survivability. As a result, each potential surrogate species should be compared directly with B. anthracis in future experimental studies.

Experiments to compare the effect of disinfectants can also be useful for examining parallels in spore resilience. Whitney et al. [39] reviewed many of the studies that have performed disinfectant trials on B. anthracis. Brazis et al. [15] compared the effects of chlorine on B. atrophaeus and B. anthracis spores and found B. atrophaeus survival to be a conservative indicator for B. anthracis survival. B. cereus spores reasonably simulate B. anthracis spore inactivation by peroxyacetic acid-based biocides, but are less reliable for hydrogen peroxide, sodium hypochlorite, and acidified sodium chlorite [213]. Rice et al. [26] examined the affect of chlorine on several B. anthracis strains and potential surrogates and found that B. thuringiensis behaviour was most similar to a virulent B. anthracis strain. However, they also found a difference between the attenuated and virulent B. anthracis strains, indicating that even very close organisms may behave differently when conditions vary. More recently, Sagripanti et al. [40] investigated the effects of various chlorides and other decontaminants on virulent B. anthracis and several potential surrogates on glass, metal, and polymeric surfaces.

Over the years many studies have focused on different bactericidal techniques for B. anthracis and their comparative effect on survival, including ultraviolet [44,48-50,214] and various chemicals [15,34,39,215]. Two of the ultraviolet studies were geared toward surrogate selection. Nicholson and Galeano [44] validated B. subtilis as a good ultraviolet surrogate for B. anthracis using the attenuated Sterne strain. However, another study found B. subtilis spores were highly resilient to ultraviolet ionizing radiation when immersed in water and concluded this species would be a poor surrogate for B. anthracis [216]. Menetrez and coworkers [48] found that B. anthracis Sterne was more resistant to ultraviolet than other surrogates, including B. thuringiensis, B. cereus and B. megaterium. Therefore, the data remain equivocal for choosing a stand-in with similar ultraviolet survival characteristics.

The results from the literature search on survivability are useful, but must be used with caution when comparing surrogates. Several authors have noted the high variability observed between spore batches and experiments [26,44]. This variability makes the translation of results from different researchers difficult. Stringent testing of differences between strains can only take place when careful experimental designs are employed, including sporulation under identical conditions and strictly conserved methods for purification and survival estimates. The overall conclusions drawn from the results of previous survivability experiments suggest that any of our potential surrogates may behave similarly to B. anthracis. As a result, individual laboratory testing is also required in order to empirically validate a surrogate choice based on theoretical considerations.

Choice of surrogate

Our goal was to examine the various possible surrogates for B. anthracis, review the criteria for selecting an appropriate surrogate, compare the potential surrogates by these criteria and, ultimately, choose the most appropriate surrogate for our purposes. After examination of the first criteria, safety of use, we are left with B. atrophaeus, B. thuringiensis, B. megaterium and B. subtilis as potential surrogates. However, after further examination of genetic relatedness and the consequential morphological differences, B. thuringiensis emerges as the most appropriate candidate for a B. anthracis surrogate. This may be a surprising choice for some researchers, based on the traditional preference for B. atrophaeus. However, further examination of published comparisons also supports B. thuringiensis as a good surrogate for B. anthracis.

We recommend B. thuringiensis as the most appropriate surrogate based upon existing empirical data. As a result of the phenotypic similarity within the B. cereus group it will be important to utilize a B. thuringiensis strain that has a publically available genome sequence, such as B. thuringiensis serovar israelensis (ATCC 35646; GenBank No. AAJM01000000). This will allow for strain-specific markers to be identified [217,218] which can be used as the basis for assays that can readily detect this strain and distinguish it from con-specifics as well as near neighbour species. We stress that additional experimental evidence is needed to confirm that B. thuringiensis and B. anthracis have similar behaviours. Data on spore survival and mobility are extremely lacking and we have identified several important knowledge gaps (Table 4). We have found only a few studies comparing spores from Bacillus species with the goal of surrogate validation and comparison [26,40,44,48,60]. We are aware of no studies that provide comparative survival of the surrogate candidates in soil or on different types of fomites, both under natural conditions and with heat, pH variance or UV radiation. In addition, there are no quantitative studies on the long-term survival of the spores in any medium. We also find very few studies that use virulent B. anthracis strains. The current literature suggests that there can be differences between the attenuated strains and the virulent strains. Therefore, in order to truly quantify and thereby confirm that our selected surrogate is the correct choice, we recommend conducting additional comparative experiments.

Table 4.

Gaps in our knowledge related to surrogate selection and model parameters.

| Gaps | Recommended action |

|---|---|

| No quantitative comparisons of spore survival on fomites | Conduct experiments using steel, laminar, plastic and other surfaces |

| No quantitative comparisons of spore survival in soil | Conduct experiments across soil types |

| No quantitative comparisons of spore survival in buffer/water | Conduct survival experiments in water or buffer |

| No long-term studies | Perform spore survival studies that are over a year long |

| Only one comparative study examining the effect of heat in various buffers | Reconfirm results |

| Only one comparative study with UV | Reconfirm results |

| Only a few studies with virulent Bacillus anthracis | Use virulent B. anthracis and compare directly to potential surrogates |

Abbreviation

BSL: biosafety level.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DG and DW conceived the study. DG, JB, PK and DW drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

David L Greenberg, Email: David.Greenberg@nau.edu.

Joseph D Busch, Email: Joseph.Busch@nau.edu.

Paul Keim, Email: Paul.Keim@nau.edu.

David M Wagner, Email: Dave.Wagner@nau.edu.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Center for Advancing Microbial Risk Assessment, which is funded by the US Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results programme and the US Department of Homeland Security University Programs (grant R3236201).

References

- Tournier JN, Ulrich RG, Quesnel-Hellmann A, Mohamadzadeh M, Stiles BG. Anthrax, toxins and vaccines: a 125-year journey targeting Bacillus anthracis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7:219–236. doi: 10.1586/14787210.7.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T, Busch JD, Ravel J, Read TD, Rhoton SD, U'Ren JM, Simonson TS, Kachur SM, Leadem RR, Cardon ML, Van Ert MN, Huynh LY, Fraser CM, Keim P. Phylogenetic discovery bias in Bacillus anthracis using single-nucleotide polymorphisms from whole-genome sequencing. PNAS. 2004;101:13536–13541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403844101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PCB. Introduction: Anthrax history, disease and ecology. Anthrax. Current Topics In Microbiology And Immunology. 2002;271:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05767-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DB, Valadares de Amorim G. Potential for aerosol dissemination of biological weapons: lessons from biological control of insects. Biosecurity and bioterrorism: Biodefense strategy, practice, and science. 2003;1:37–42. doi: 10.1089/15387130360514814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt PL. WATER AND BIOTERRORISM: Preparing for the Potential Threat to U.S. Water Supplies and Public Health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:213–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Group of Consultants. Health Aspects of Chemical and Biological Weapons. Geneva: WHO; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Fritze D, Pukall R. Reclassification of bioindicator strains Bacillus subtilis DSM 675 and Bacillus subtilis DSM 2277 as Bacillus atrophaeus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:35–37. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura LK. Taxonomic Relationship of Black-Pigmented Bacillus subtilis Strains and a Proposal for Bacillus atrophaeus sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:295–300. doi: 10.1099/00207713-39-3-295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regis E. The Biology of Doom. New York: Henry Holt and Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Carey LF, Amant DCS, Guelta MA, Proving E. Production of Bacillus Spores as a Simulant for Biological Warfare Agents. EDGEWOOD CHEMICAL BIOLOGICAL CENTER ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND; 2004. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Regis E. The Biology of Doom. The History of America's Secret Germ Warfare Project. New York: Henry Holt & Co; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart AL, Wilkening DA. Degradation of biological weapons agents in the environment: implications for terrorism response. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:2736–2743. doi: 10.1021/es048705e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb RW, Schneiter R. The germicidal and sporicidal efficacy of methyl bromide for Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 1950;59:401–412. doi: 10.1128/jb.59.3.401-412.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiter R, Kolb RW. In: Supplement No. 207 to the Public Health Reports. NPHS, editor. 1948. Heat resistance studies with spores of Bacillus anthracis and related aerobic bacilli in hair and bristles; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brazis AR, Leslie JE, Kabler PW, Woodward RL. The inactivation of spores of Bacillus globigii and Bacillus anthracis by free available chlorine. Appl Microbiol. 1958;6:338–342. doi: 10.1128/am.6.5.338-342.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faille C, Dennin L, Bellon-Fontaine MN, Benezech T. Cleanability of stainless steel surfaces soiled by Bacillus thuringiensis spores under various flow conditions. Biofouling. 1999;14:143–151. doi: 10.1080/08927019909378405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner MP, Cruz P, Stetzenbach LD, Klima-Comba AK, Stevens VL, Cronin TD. Determination of the efficacy of two building decontamination strategies by surface sampling with culture and quantitative PCR analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4740–4747. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4740-4747.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DJ, Sickbert-Bennett E, Gergen MF, Rutala WA. Efficacy of selected hand hygiene agents used to remove Bacillus atrophaeus (a surrogate of Bacillus anthracis) from contaminated hands. Jama. 2003;289:1274–1277. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radziminski C, Ballantyne L, Hodson J, Creason R, Andrews RC, Chauret C. Disinfection of Bacillus subtilis spores with chlorine dioxide: a bench-scale and pilot-scale study. Water Res. 2002;36:1629–1639. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(01)00355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman SP, Scott EM, Hutchinson EP. Hypochlorite effects on spores and spore forms of Bacillus subtilis and on a spore lytic enzyme. J Appl Bacteriol. 1984;56:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1984.tb01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt LR, Waites WM. The effect of chlorine on spores of Clostridium bifermentans, Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus cereus. J Gen Microbiol. 1975;89:337–344. doi: 10.1099/00221287-89-2-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuchat LR, Pettigrew CA, Tremblay ME, Roselle BJ, Scouten AJ. Lethality of chlorine, chlorine dioxide, and a commercial fruit and vegetable sanitizer to vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus cereus and spores of Bacillus thuringiensis. Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;32:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s10295-005-0212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SB, Setlow P. Mechanisms of killing of Bacillus subtilis spores by hypochlorite and chlorine dioxide. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95:54–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortezzo DE, Koziol-Dube K, Setlow B, Setlow P. Treatment with oxidizing agents damages the inner membrane of spores of Bacillus subtilis and sensitizes spores to subsequent stress. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:838–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose LJ, Rice EW, Jensen B, Murga R, Peterson A, Donlan RM, Arduino MJ. Chlorine inactivation of bacterial bioterrorism agents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:566–568. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.1.566-568.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice EW, Adcock NJ, Sivaganesan M, Rose LJ. Inactivation of spores of Bacillus anthracis Sterne, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis by chlorination. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5587–5589. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5587-5589.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcomyn CA, Bushway KE, Henley MV. Inactivation of biological agents using neutral oxone-chloride solutions. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:2759–2764. doi: 10.1021/es052146+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreske AC, Ryu JH, Beuchat LR. Evaluation of chlorine, chlorine dioxide, and a peroxyacetic acid-based sanitizer for effectiveness in killing Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis spores in suspensions, on the surface of stainless steel, and on apples. Journal Of Food Protection. 2006;69:1892–1903. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.8.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo JG, Rice EW, Bishop PL. Persistence and decontamination of Bacillus atrophaeus subsp. globigii spores on corroded iron in a model drinking water system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cross JB, Currier RP, Torraco DJ, Vanderberg LA, Wagner GL, Gladen PD. Killing of bacillus spores by aqueous dissolved oxygen, ascorbic acid, and copper ions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:2245–2252. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.2245-2252.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melly E, Cowan AE, Setlow P. Studies on the mechanism of killing of Bacillus subtilis spores by hydrogen peroxide. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;93:316–325. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loshon CA, Melly E, Setlow B, Setlow P. Analysis of the killing of spores of Bacillus subtilis by a new disinfectant, Sterilox. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;91:1051–1058. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis RE, Shin SY. Mineralization and responses of bacterial spores to heat and oxidative agents. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:375–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagripanti JL, Bonifacino A. Comparative sporicidal effects of liquid chemical agents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:545–551. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.545-551.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagripanti JL, Bonifacino A. Comparative sporicidal effect of liquid chemical germicides on three medical devices contaminated with spores of Bacillus subtilis. Am J Infect Control. 1996;24:364–371. doi: 10.1016/S0196-6553(96)90024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SB, Setlow P. Mechanisms of killing of Bacillus subtilis spores by Decon and Oxone, two general decontaminants for biological agents. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:289–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2004.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JV, Sabourin CL, Choi YW, Richter WR, Rudnicki DC, Riggs KB, Taylor ML, Chang J. Decontamination assessment of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus subtilis, and Geobacillus stearothermophilus spores on indoor surfaces using a hydrogen peroxide gas generator. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;99:739–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong G, Watson I, Stewart-Tull D. Inactivation of B. cereus spores on agar, stainless steel or in water with a combination of Nd: YAG laser and UV irradiation. INNOVATIVE FOOD SCIENCE & EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES. 2006;7:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney EAS, Beatty ME, Taylor TH, Weyant R, Sobel J, Arduino MJ, Ashford DA. Inactivation of Bacillus anthracis spores. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:623–627. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagripanti JL, Carrera M, Insalaco J, Ziemski M, Rogers J, Zandomeni R. Virulent spores of Bacillus anthracis and other Bacillus species deposited on solid surfaces have similar sensitivity to chemical decontaminants. Journal Of Applied Microbiology. 2007;102:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidova TN, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic inactivation of Bacillus spores, mediated by phenothiazinium dyes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:6918–6925. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6918-6925.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidova TN, Hamblinl MR. In: Prodceedings of SPIE; Bellingham, WA. Kessel D, editor. 2005. Anthrtax surrogate spores are destroyed by PDT mediated by phenothiazinium dyes. [Google Scholar]

- Montville TJ, De Siano T, Nock A, Padhi S, Wade D. Inhibition of Bacillus anthracis and potential surrogate bacilli growth from spore inocula by nisin and other antimicrobial peptides. Journal Of Food Protection. 2006;69:2529–2533. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.10.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WL, Galeano B. UV resistance of Bacillus anthracis spores revisited: validation of Bacillus subtilis spores as UV surrogates for spores of B. anthracis Sterne. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1327–1330. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.2.1327-1330.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. Resistance of spores of Bacillus species to ultraviolet light. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2001;38:97–104. doi: 10.1002/em.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myasnik M, Manasherob R, Ben-Dov E, Zaritsky A, Margalith Y, Barak Z. Comparative sensitivity to UV-B radiation of two Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies and other Bacillus sp. Curr Microbiol. 2001;43:140–143. doi: 10.1007/s002840010276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griego VM, Spence KD. Inactivation of Bacillus thuringiensis spores by ultraviolet and visible light. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:906–910. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.5.906-910.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menetrez MY, Foarde KK, Webber TD, Dean TR, Betancourt DA. Efficacy of UV irradiation on eight species of Bacillus. Journal Of Environmental Engineering And Science. 2006;5:329–334. doi: 10.1139/S05-041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blatchley ER, Meeusen A, Aronson AI, Brewster L. Inactivation of Bacillus spores by ultraviolet or gamma radiation. Journal Of Environmental Engineering-Asce. 2005;131:1245–1252. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(2005)131:9(1245). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JK, Ewell M. Examination of peak power dependence in the UV inactivation of bacterial spores. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5830–5832. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5830-5832.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Paek KH, Ju WT, Lee Y. Sterilization of bacteria, yeast, and bacterial endospores by atmospheric-pressure cold plasma using helium and oxygen. J Microbiol. 2006;44:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfinstine SL, Vargas-Aburto C, Uribe RM, Woolverton CJ. Inactivation of Bacillus endospores in envelopes by electron beam irradiation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7029–7032. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7029-7032.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr SE, Dickson JS. Destruction of Bacillus anthracis strain Sterne 34F2 spores in postal envelopes by exposure to electron beam irradiation. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;37:17–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiter R, Kolb RW. In: Supplement No. 207 to the Public Health Reports. Public Health Service N, editor. 1948. Heat resistance studies with spores of Bacillus anthracis and related aerobic bacilli in hair and bristles; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Paik WW, Sherry EJ, Stern JA. Thermal Death Of Bacillus Subtilis Var Niger Spores On Selected Lander Capsule Surfaces. Applied Microbiology. 1969;18:901. doi: 10.1128/am.18.5.901-905.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaman TC, Gerhardt P. Heat resistance of bacterial spores correlated with protoplast dehydration, mineralization, and thermal adaptation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1242–1246. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.6.1242-1246.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop A, Manas P, Condon S. Sporulation temperature and heat resistance of Bacillus spores: A review. Journal Of Food Safety. 1999;19:57–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4565.1999.tb00234.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice EW, Rose LJ, Johnson CH, Boczek LA, Arduino MJ, Reasoner DJ. Boiling and Bacillus spores. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1887–1888. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.040158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak JS, Call J, Tomasula P, Luchansky JB. An assessment of pasteurization treatment of water, media, and milk with respect to Bacillus spores. Journal Of Food Protection. 2005;68:751–757. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montville TJ, Dengrove R, De Siano T, Bonnet M, Schaffner DW. Thermal resistance of spores from virulent strains of Bacillus anthracis and potential surrogates. J Food Prot. 2005;68:2362–2366. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.11.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PC, Frawley DA, Bull RL. Heat activation/shock temperatures for Bacillus anthracis spores and the issue of spore plate counts versus true numbers of spores. J Microbiol Methods. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scurrah KJ, Robertson RE, Craven HM, Pearce LE, Szabo EA. Inactivation of Bacillus spores in reconstituted skim milk by combined high pressure and heat treatment. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:172–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner RG, Lillford PJ. Effects of temperature and heat activation on germination of individual spores of Bacillus subtilis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1999;29:228–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulla LA, St Julian G, Rhodes RA, Hesseltine CW. Scanning electron and phase-contrast microscopy of bacterial spores. Appl Microbiol. 1969;18:490–495. doi: 10.1128/am.18.3.490-495.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp M, Leighton TJ, Wheeler KE, Malkin AJ. The high-resolution architecture and structural dynamics of Bacillus spores. Biophys J. 2005;88:603–608. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp M, Leighton TJ, Wheeler KE, Malkin AJ. Architecture and high-resolution structure of Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus cereus spore coat surfaces. Langmuir. 2005;21:7892–7898. doi: 10.1021/la050412r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp M, Leighton TJ, Wheeler KE, Pitesky ME, Malkin AJ. Bacillus atrophaeus outer spore coat assembly and ultrastructure. Langmuir. 2005;21:10710–10716. doi: 10.1021/la0517437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolock RA, Li G, Bleckmann C, Burggraf L, Fuller DC. Atomic force microscopy of Bacillus spore surface morphology. Micron. 2006;37:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wig A, Arakawa E, Passian A, Thundat T. Photothermal spectroscopy of Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus cereus with microcantilevers. Sensors and Actuators. 2004;B114:206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa ET, Lavrik NV, Datskos PG. Detection of anthrax simulants with microcalorimetric spectroscopy: Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus cereus spores. Appl Opt. 2003;42:1757–1762. doi: 10.1364/AO.42.001757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratis-Cullum DN, Griffin GD, Mobley J, Vass AA, Vo-Dinh T. A miniature biochip system for detection of aerosolized Bacillus globigii spores. Anal Chem. 2003;75:275–280. doi: 10.1021/ac026068+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich MP, Christensen DR, Coyne SR, Craw PD, Henchal EA, Sakai SH, Swenson D, Tholath J, Tsai J, Weir AF, Norwood DA. Evaluation of the Cepheid GeneXpert system for detecting Bacillus anthracis. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;100:1011–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquharson S, Grigely L, Khitrov V, Smith W, Sperry JF, Fenerty G. Detecting Bacillus cereus spores on a mail sorting system using Raman spectroscopy. Journal Of Raman Spectroscopy. 2004;35:82–86. doi: 10.1002/jrs.1111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radnedge L, Agron PG, Hill KK, Jackson PJ, Ticknor LO, Keim P, Andersen GL. Genome differences that distinguish Bacillus anthracis from Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:2755–2764. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.5.2755-2764.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane SR, Letant SE, Murphy GA, Alfaro TM, Krauter PW, Mahnke R, Legler TC, Raber E. Rapid, high-throughput, culture-based PCR methods to analyze samples for viable spores of Bacillus anthracis and its surrogates. J Microbiol Methods. 2009;76:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saikaly PE, Barlaz MA, de Los Reyes FL. Development of quantitative real-time PCR assays for detection and quantification of surrogate biological warfare agents in building debris and leachate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:6557–6565. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00779-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Rothman RE, Hardick J, Kuroki M, Hardick A, Doshi V, Ramachandran P, Gaydos CA. Rapid polymerase chain reaction-based screening assay for bacterial biothreat agents. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:388–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride MT, Masquelier D, Hindson BJ, Makarewicz AJ, Brown S, Burris K, Metz T, Langlois RG, Tsang KW, Bryan R, Anderson DA, Venkateswaran KS, Milanovich FP, Colston BW Jr. Autonomous detection of aerosolized Bacillus anthracis and Yersinia pestis. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5293–5299. doi: 10.1021/ac034722v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindson BJ, McBride MT, Makarewicz AJ, Henderer BD, Setlur US, Smith SM, Gutierrez DM, Metz TR, Nasarabadi SL, Venkateswaran KS, Farrow SW, Colston BW Jr, Dzenitis JM. Autonomous detection of aerosolized biological agents by multiplexed immunoassay with polymerase chain reaction confirmation. Anal Chem. 2005;77:284–289. doi: 10.1021/ac0489014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak JC, Shugard EE, Mosier BP, Renzi RF, Caton PF, Ferko SM, Van de Vreugde JL, Yee DD, Haroldsen BL, VanderNoot VA. Autonomous microfluidic sample preparation system for protein profile-based detection of aerosolized bacterial cells and spores. Anal Chem. 2007;79:5763–5770. doi: 10.1021/ac070567z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SJ, Terray A, Leski TA, Arnold J, Stroud R. Discovery of a significant optical chromatographic difference between spores of Bacillus anthracis and its close relative, Bacillus thuringiensis. Anal Chem. 2006;78:3221–3225. doi: 10.1021/ac052221z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs MD, Mansfield B, Yip P, Cohen SJ, Sonenshein AL, Hitt BA, Davis CE. Novel technology for rapid species-specific detection of Bacillus spores. Biomol Eng. 2006;23:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb-Snyder E, Gullett B, Ryan S, Oudejans L, Touati A. Development of size-selective sampling of Bacillus anthracis surrogate spores from simulated building air intake mixtures for analysis via laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Appl Spectrosc. 2006;60:860–870. doi: 10.1366/000370206778062192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JL, De Lucia FC Jr, Munson CA, Miziolek AW. Standoff detection of chemical and biological threats using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Appl Spectrosc. 2008;62:353–363. doi: 10.1366/000370208784046759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson CA, Gottfried JL, Snyder EG, De Lucia FC Jr, Gullett B, Miziolek AW. Detection of indoor biological hazards using the man-portable laser induced breakdown spectrometer. Appl Opt. 2008;47:G48–57. doi: 10.1364/AO.47.000G48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EG, Munson CA, Gottfried JL, De Lucia FC Jr, Gullett B, Miziolek A. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy for the classification of unknown powders. Appl Opt. 2008;47:G80–87. doi: 10.1364/AO.47.000G80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme C, Verreault D, Ho J, Duchaine C. Flow cytometry sorting protocol of Bacillus spore using ultraviolet laser and autofluorescence as main sorting criterion. Journal Of Fluorescence. 2006;16:733–737. doi: 10.1007/s10895-006-0129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathout Y, Demirev PA, Ho YP, Bundy JL, Ryzhov V, Sapp L, Stutler J, Jackman J, Fenselau C. Identification of Bacillus spores by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-mass spectrometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4313–4319. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4313-4319.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathout Y, Setlow B, Cabrera-Martinez RM, Fenselau C, Setlow P. Small, acid-soluble proteins as biomarkers in mass spectrometry analysis of Bacillus spores. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1100–1107. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.2.1100-1107.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhanany E, Barak R, Fisher M, Kobiler D, Altboum Z. Detection of specific Bacillus anthracis spore biomarkers by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:2110–2116. doi: 10.1002/rcm.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warscheid B, Fenselau C. Characterization of Bacillus spore species and their mixtures using postsource decay with a curved-field reflectron. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5618–5627. doi: 10.1021/ac034200f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribil PA, Patton E, Black G, Doroshenko V, Fenselau C. Rapid characterization of Bacillus spores targeting species-unique peptides produced with an atmospheric pressure matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization source. J Mass Spectrom. 2005;40:464–474. doi: 10.1002/jms.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanha ER, Fox A, Fox KF. Rapid discrimination of Bacillus anthracis from other members of the B. cereus group by mass and sequence of "intact" small acid soluble proteins (SASPs) using mass spectrometry. J Microbiol Methods. 2006;67:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson DN, La Duc MT, Haskins WE, Gornushkin I, Winefordner JD, Powell DH, Venkateswaran K. Species differentiation of a diverse suite of Bacillus spores by mass spectrometry-based protein profiling. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:475–482. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.475-482.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergenson DP, Pitesky ME, Frank M, Horn JM, Gard EE. Distinguishing Seven Species of Bacillus Spores Using BioAerosol Mass Spectrometry. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) L, CA: USDOE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs MD, Zapata AM, Nazarov EG, Miller RA, Costa IS, Sonenshein AL, Davis CE. Detection of biological and chemical agents using differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) technology. Ieee Sensors Journal. 2005;5:696–703. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2005.845515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demirev PA, Feldman AB, Kowalski P, Lin JS. Top-down proteomics for rapid identification of intact microorganisms. Anal Chem. 2005;77:7455–7461. doi: 10.1021/ac051419g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvecchio VG, Connolly JP, Alefantis TG, Walz A, Quan MA, Patra G, Ashton JM, Whittington JT, Chafin RD, Liang X, Grewal P, Khan AS, Mujer CV. Proteomic profiling and identification of immunodominant spore antigens of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:6355–6363. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00455-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min J, Lee J, Deininger RA. Simple and rapid method for detection of bacterial spores in powder useful for first responders. J Environ Health. 2006;68:34–37. 44, 46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch D, Brozik S. In: Low level detection of a Bacillus anthracis simulant using a love-wave biosensors. Technology MSa, editor. Sandia National Laboratories; 2003. p. 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfinstine SL, Lavrentovich OD, Woolverton CJ. Lyotropic liquid crystal as a real-time detector of microbial immune complexes. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;43:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens JR. Conference on Obscuration and Aerosol Research. Los Alamos National Lab; 1996. Flourescence cross section meaurements of biological agent simulants. [Google Scholar]

- Sainathrao S, Mohan KV, Atreya C. Gamma-phage lysin PlyG sequence-based synthetic peptides coupled with Qdot-nanocrystals are useful for developing detection methods for Bacillus anthracis by using its surrogates, B. anthracis-Sterne and B. cereus-4342. BMC Biotechnol. 2009;9:67. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephans JR. In: Measurements of the Ultraviolet Fluorescence Cross Sections and Spectra of Bacillus Anthracis Simulants. Lab LAN, editor. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens JR. Identification of BW agents simulants on building surfaces by infrared reflectance spectroscopy. CBW Protection Symposium; May 10-13; Stockholm, Sweden. 1998. p. 11.

- Utrup LJ, Werner K, Frey AH. Minimizing pathogenic bacteria, including spores, in indoor air. J Environ Health. 2003;66:19–26. 29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA, Willeke K, Mainelis G, Adhikari A, Wang HX, Reponen T, Grinshpun SA. Assessment of electrical charge on airborne microorganisms by a new bioaerosol sampling method. Journal Of Occupational And Environmental Hygiene. 2004;1:127–138. doi: 10.1080/15459620490424357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Burton N, Adhikari A, Grinshpun SA, Hornung R, Reponen T. The effect of filter material on bioaerosol collection of Bacillus subtilis spores used as a Bacillus anthracis simulant. J Environ Monit. 2005;7:475–480. doi: 10.1039/b500056d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lighthart B, Prier K, Bromenshenk J. Detection of aerosolized bacterial spores (Bacillus atrophaeus) using free-flying honey bees (Hymenoptera apidae) as collectors. Aerobiologica. 2004;20:191–195. doi: 10.1007/s10453-004-1182-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teschke K, Chow Y, Bartlett K, Ross A, van Netten C. Spatial and temporal distribution of airborne Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki during an aerial spray program for gypsy moth eradication. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2001;109:47–54. doi: 10.2307/3434920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadares De Amorim G, Whittome B, Shore B, Levin DB. Identification of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain HD1-Like bacteria from environmental and human samples after aerial spraying of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, with Foray 48B. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1035–1043. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1035-1043.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauter P, Biermann A, Larsen L. Transport efficiency and deposition velocity of fluidized spores in ventilation ducts. Aerobiologia. 2005;21:155–172. doi: 10.1007/s10453-005-9001-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty GM, Hadley DR, o'Conner PR. In: Engineered aerosol production for laboratory scale chemical/biological test and evaluation. Energy Do, editor. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; 2007. p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Krauter P, Biermann A. Reaerosolization of Fluidized Spores in Ventilation Systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Scott Duncan EJ, Kournikakis B, Ho J, Hill I. Pulmonary deposition of aerosolized Bacillus atrophaeus in a swine model due to exposure from a simulated anthrax letter incident. Inhalation Toxicology. 2009;21:141–152. doi: 10.1080/08958370802412629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobniewski FA. Bacillus-Cereus And Related Species. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1993;6:324–338. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason E, Caugant DA, Olsen I, Kolsto AB. Genetic structure of population of Bacillus cereus and B. thuringiensis isolates associated with periodontitis and other human infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1615–1622. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1615-1622.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Heumann M, Sokolow R, Foster LR, Bryant R, Skeels M. Public health implications of the microbial pesticide Bacillus thuringiensis: an epidemiological study, Oregon, 1985-86. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:848–852. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.80.7.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock JT, Schaffer CR, Sjoblad RD. A Comparative Review Of The Mammalian Toxicity Of Bacillus Thuringiensis-Based Pesticides. Pesticide Science. 1995;45:95–105. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780450202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samples JR, Buettner H. Ocular Infection Caused By A Biological Insecticide. Journal Of Infectious Diseases. 1983;148:614–614. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez E, Ramisse F, Ducoureau JP, Cruel T, Cavallo JD. Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. konkukian (serotype H34) superinfection: case report and experimental evidence of pathogenicity in immunosuppressed mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2138–2139. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2138-2139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SG, Goodbrand RB, Ahmed R, Kasatiya S. Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolated in a gastroenteritis outbreak investigation. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1995;21:103–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1995.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash C, Farrow JAE, Wallbanks S, Collins MD. Phylogenetic Heterogeneity Of The Genus Bacillus Revealed By Comparative-Analysis Of Small-Subunit-Ribosomal Rna Sequences. Letters In Applied Microbiology. 1991;13:202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Brumlick MJ, Bielawska-Drozd A, Zakowska D, Liang X, Spalletta RA, Patra G, DelVecchio VG. Genetic diversity among Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus and Bacilus thuringiensis strains using repetative element polymorphisms-PCR. Polish Journal of Microbiology. 2004;53:215–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton JE, Oshota OJ, Silman NJ. Differential identification of Bacillus anthracis from environmental Bacillus species using microarray analysis. Journal Of Applied Microbiology. 2006;101:754–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritze D. Taxonomy of the Genus Bacillus and related genera: The aerobic endospore-fromiung bacteria. Phytopathology. 2004;94:1245–1248. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohar M, Gilois N, Graveline R, Garreau C, Sanchis V, Lereclus D. A comparative study of Bacillus cereus, Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus anthracis extracellular proteomes. Proteomics. 2005;5:3696–3711. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han CS, Xie G, Challacombe JF, Altherr MR, Bhotika SS, Bruce D, Campbell CS, Campbell ML, Chen J, Chertkov O, Cleland C, Dimitrijevic M, Doggett NA, Fawcett JJ, Glavina T, Goodwin LA, Hill KK, Hitchcock P, Jackson PJ, Keim P, Kewalramani AR, Longmire J, Lucas S, Malfatti S, McMurry K, Meincke LJ, Misra M, Moseman BL, Mundt M, Munk AC. et al. Pathogenomic sequence analysis of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolates closely related to Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3382–3390. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3382-3390.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason E, Okstad OA, Caugant DA, Johansen HA, Fouet A, Mock M, Hegna I, Kolsto. Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis--one species on the basis of genetic evidence. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2627–2630. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.6.2627-2630.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason E, Tourasse NJ, Meisal R, Caugant DA, Kolsto AB. Multilocus sequence typing scheme for bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:191–201. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.191-201.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KK, Ticknor LO, Okinaka RT, Asay M, Blair H, Bliss KA, Laker M, Pardington PE, Richardson AP, Tonks M, Beecher DJ, Kemp JD, Kolsto AB, Wong AC, Keim P, Jackson PJ. Fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1068–1080. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.1068-1080.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova N, Sorokin A, Anderson I, Galleron N, Candelon B, Kapatral V, Bhattacharyya A, Reznik G, Mikhailova N, Lapidus A, Chu L, Mazur M, Goltsman E, Larsen N, D'Souza M, Walunas T, Grechkin Y, Pusch G, Haselkorn R, Fonstein M, Ehrlich SD, Overbeek R, Kyrpides N. Genome sequence of Bacillus cereus and comparative analysis with Bacillus anthracis. Nature. 2003;423:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature01582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PJ, Hill KK, Laker MT, Ticknor LO, Keim P. Genetic comparison of Bacillus anthracis and its close relatives using amplified fragment length polymorphism and polymerase chain reaction analysis. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:263–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim P, Kalif A, Schupp J, Hill K, Travis SE, Richmond K, Adair DM, Hugh-Jones M, Kuske CR, Jackson P. Molecular evolution and diversity in Bacillus anthracis as detected by amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:818–824. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.818-824.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim P, Klevytska AM, Price LB, Schupp JM, Zinser G, Smith KL, Hugh-Jones ME, Okinaka R, Hill KK, Jackson PJ. Molecular diversity in Bacillus anthracis. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:215–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest FG, Barker M, Baillie LW, Holmes EC, Maiden MC. Population structure and evolution of the Bacillus cereus group. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7959–7970. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7959-7970.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasko DA, Ravel J, Okstad OA, Helgason E, Cer RZ, Jiang L, Shores KA, Fouts DE, Tourasse NJ, Angiuoli SV, Kolonay J, Nelson WC, Kolsto AB, Fraser CM, Read TD. The genome sequence of Bacillus cereus ATCC 10987 reveals metabolic adaptations and a large plasmid related to Bacillus anthracis pXO1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:977–988. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read TD, Peterson SN, Tourasse N, Baillie LW, Paulsen IT, Nelson KE, Tettelin H, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Gill SR, Holtzapple EK, Okstad OA, Helgason E, Rilstone J, Wu M, Kolonay JF, Beanan MJ, Dodson RJ, Brinkac LM, Gwinn M, DeBoy RT, Madpu R, Daugherty SC, Durkin AS, Haft DH, Nelson WC, Peterson JD, Pop M, Khouri HM, Radune D. et al. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature. 2003;423:81–86. doi: 10.1038/nature01586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd SJ, Moir AJ, Johnson MJ, Moir A. Genes of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus anthracis encoding proteins of the exosporium. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3373–3378. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3373-3378.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PC. Definitive identification of Bacillus anthracis--a review. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:237–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjevac S, Hilaire V, Lisanti O, Ramisse F, Hernandez E, Cavallo JD, Pourcel C, Vergnaud G. Comparison of minisatellite polymorphisms in the Bacillus cereus complex: a simple assay for large-scale screening and identification of strains most closely related to Bacillus anthracis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:6613–6623. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6613-6623.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Cote JC. Phylogenetic relationships between Bacillus species and related genera inferred from comparison of 3' end 16 S rDNA and 5' end 16S-23 S ITS nucleotide sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:695–704. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterday WR, Van Ert MN, Simonson TS, Wagner DM, Kenefic LJ, Allender CJ, Keim P. Use of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the plcR gene for specific Identification of Bacillus anthracis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43:1995–1997. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1995-1997.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterday WR, Van Ert MN, Zanecki S, Keim P. Specific detection of bacillus anthracis using a TaqMan mismatch amplification mutation assay. BioTechniques. 2005;38:731–735. doi: 10.2144/05385ST03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre P, Couture-Tosi E, Mock M. A collagen-like surface glycoprotein is a structural component of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;45:169–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.03000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rety S, Salamitou S, Garcia-Verdugo I, Hulmes DJ, Le Hegarat F, Chaby R, Lewit-Bentley A. The crystal structure of the Bacillus anthracis spore surface protein BclA shows remarkable similarity to mammalian proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43073–43078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaysi G. The Endospore Of Bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1948;12:19–77. doi: 10.1128/br.12.1.19-77.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth AD, Ohye DF, Murrell WG. The composition and structure of bacterial spores. J Cell Biol. 1963;16:579–592. doi: 10.1083/jcb.16.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt P, Ribi E. Ultrastructure Of The Exosporium Enveloping Spores Of Bacillus Cereus. J Bacteriol. 1964;88:1774–1789. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.6.1774-1789.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaysi G. Further Observations On The Spodogram Of Bacillus Cereus Endospore. J Bacteriol. 1965;90:453–455. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.2.453-455.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachisuka Y, Kozuka S, Tsujikawa M. Exosporia and appendages of spores of Bacillus species. Microbiol Immunol. 1984;28:619–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1984.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton S, Moir AJG, Baillie L, Moir A. Characterization of the exosporium of Bacillus cereus. Journal Of Applied Microbiology. 1999;87:241–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng JS, Tsai WC, Chou CC. Surface characteristics of Bacillus cereus and its adhesion to stainless steel. Int J Food Microbiol. 2001;65:105–111. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00517-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaman TC, Pankratz HS, Gerhardt P. Ultrastructure of the Exosporium and Underlying Inclusions in Spores of Bacillus megaterium Strains. J Bacteriol. 1972;109:1198–1209. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.3.1198-1209.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshikawa T, Yamazaki M, Yoshimi M, Ogawa S, Yamada A, Watabe K, Torii M. Surface hydrophobicity of spores of Bacillus spp. Journal of General Microbiology. 1989;135:2717–2722. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-10-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa JCF, Silva MT, Balassa G. An exosporium-like outer layer in Bacillus subtilis spores. Nature. 1976;263:53–54. doi: 10.1038/263053a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MJ, Roth IL. Ultrastructural Differences In Exosporium Of Sterne And Vollum Strains Of Bacillus Anthracis. Canadian Journal Of Microbiology. 1968;14:1297. doi: 10.1139/m68-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaysi G. On the structure and nature of the endospore in strain C3 of Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1955;69:130–138. doi: 10.1128/jb.69.2.130-138.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima K, Sato T. Fine Filaments On Outside Of Exosporium Of Bacillus Anthracis Spores. Journal Of Bacteriology. 1966;91:2382. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.6.2382-2384.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachisuka Y, Kuno T. Filamentous appendages of Bacillus cereus spores. Jpn J Microbiol. 1976;20:555–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1976.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaman TC, Pankratz HS, Gerhardt P. Ultrastructure of the exosporium and underlying inclusions in spores of Bacillus megaterium strains. J Bacteriol. 1972;109:1198–1209. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.3.1198-1209.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa JC, Silva MT, Balassa G. An exosporium-like outer layer in Bacillus subtilis spores. Nature. 1976;263:53–54. doi: 10.1038/263053a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driks A. Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.1-20.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu H, Watabe K. Assembly and genetics of spore protective structures. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:434–444. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel DB, Bulla LA Jr. Electron Microscope Study of Sporulation and Parasporal Crystal Formation in Bacillus thuringiensis. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:1472–1481. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1472-1481.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt P, Pankratz HS, Scherrer R. Fine Structure of the Bacillus thuringiensis Spore. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976;32:438–440. doi: 10.1128/aem.32.3.438-440.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova TA, Mikhailov AM, Tyurin VS, Azizbekyan RR. The fine structure of spores and crystals in various Bacillus thuringiensis serotypes. MIKROBIOLOGIYA. 1984;53:455–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle R, Nedjat-Haiem F, Singh J. Hydrophobic characteristics of Bacillus spores. Current Microbiology. 1984;10:329–332. doi: 10.1007/BF01626560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zandomeni RO, Fitzgibbon JE, Carrera M, Steubing E, Rogers JE, Sagripanti J-L. In: Spore Size Comparison Between Several Bacillus Species. MD G-CIAPG, editor. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera M, Zandomeni RO, Fitzgibbon J, Sagripanti JL. Difference between the spore sizes of Bacillus anthracis and other Bacillus species. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102:303–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lighthart B. In: Atmosphere Microbial Aerosols. Lighthart B, Mohr AJ, editor. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1994. Physics of microbial bioaerosols; pp. 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cox CS. In: Bioaerosols handbook. Cox CS, Wathes CM, editor. London: Lewis; 1995. Physical aspects of bioaerosols; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera M, Zandomeni RO, Sagripanti JL. Wet and dry density of Bacillus anthracis and other Bacillus species. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;105:68–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaax NK, Davis KJ, Geisbert TJ, Vogel P, Jaax GP, Topper M, Jahrling PB. Lethal experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with Ebola-Zaire (Mayinga) virus by the oral and conjunctival route of exposure. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:140–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baweja RB, Zaman MS, Mattoo AR, Sharma K, Tripathi V, Aggarwal A, Dubey GP, Kurupati RK, Ganguli M, Chaudhury NK, Sen S, Das TK, Gade WN, Singh Y. Properties of Bacillus anthracis spores prepared under various environmental conditions. Arch Microbiol. 2008;189:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirena S, Scagliosi G. Lavori E Lezioni Originali. Riforma medicia. 1894;2:340–343. [Google Scholar]

- Szekely Av. Beitrag zur Lebensdauer der Milzbrandsporen. Zeit Hygiene Infectionskrankheiten. 1903;44:359–363. doi: 10.1007/BF02217070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busson B. Ein beitrag zur Kenntnis der Lebensdauer von Bacterium coli und Milzbrandsporen. Centralbl Bakteriol, Parasitenkd Infektionskr. 1911;58:505–509. [Google Scholar]