Abstract

The neuromodulator dopamine affects learning and memory formation and their likely physiological correlates, long-term depression and potentiation, in animals and humans. It is known from animal experiments that dopamine exerts a dosage-dependent, inverted U-shaped effect on these functions. However, this has not been explored in humans so far. In order to reveal a non-linear dose-dependent effect of dopamine on cortical plasticity in humans, we explored the impact of 25, 100 and 200 mg of l-dopa on transcranial direct current (tDCS)-induced plasticity in twelve healthy human subjects. The primary motor cortex served as a model system, and plasticity was monitored by motor evoked potential amplitudes elicited by transcranial magnetic stimulation. As compared to placebo medication, low and high dosages of l-dopa abolished facilitatory as well as inhibitory plasticity, whereas the medium dosage prolonged inhibitory plasticity, and turned facilitatory plasticity into inhibition. Thus the results show clear non-linear, dosage-dependent effects of dopamine on both facilitatory and inhibitory plasticity, and support the assumption of the importance of a specific dosage of dopamine optimally suited to improve plasticity. This might be important for the therapeutic application of dopaminergic agents, especially for rehabilitative purposes, and explain some opposing results in former studies.

Introduction

Dopamine (DA) has a major impact on cognitive functions such as learning and memory formation. This effect is not linear. Insufficient or excessive DA impairs cognitive functions (Cai & Arnsten, 1997; Goldman-Rakic et al. 2000; Seamans & Yang, 2004), whereas medium dosages improve them (Seamans & Yang, 2004; Williams & Castner, 2006; Bertolino et al. 2009). The likely basis for the impact of DA on cognition is its modulating effect on neuroplasticity, i.e. long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) (Seamans & Yang, 2004; O’Carroll et al. 2006; Calabresi et al. 2007; Kung et al. 2007; Kuo et al. 2008; Lang et al. 2008). Similar to its effect on cognition, it is suggested that DA affects neuroplasticity in a non-linear, dosage-dependent manner (Seamans & Yang, 2004; Kolomiets et al. 2009). However, specific knowledge about concentration-dependent non-linear effects of dopamine on plasticity in humans is sketchy.

Here we aimed to characterize the dose-dependent effect of l-dopa on motor cortex plasticity in humans. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) was administered for plasticity induction (Nitsche et al. 2008). tDCS hyperpolarizes or depolarizes neuronal membranes at a subthreshold level, dependent on stimulation polarity. If tDCS is applied for several minutes, anodal stimulation enhances and cathodal stimulation reduces cortical excitability for about 1 h after the end of stimulation (Nitsche & Paulus, 2001; Nitsche et al. 2003a). The respective neuroplastic alterations are thought to depend on neuronal calcium influx, because they are inhibited by NMDA receptor and calcium channel block (Liebetanz et al. 2002; Nitsche et al. 2003b). Moreover, it was shown in animal experiments that anodal tDCS enhances intracellular calcium concentration (Islam et al. 1995). Thus tDCS might exert its neuroplastic effects by modulation of intracellular calcium, as shown for LTP and LTD in animal experiments (Lisman, 2001).

In a former study 100 mg l-dopa, which improves learning in humans (Flöel et al. 2005), selectively prolonged and enhanced focal synapse-specific facilitatory plasticity as induced by a paired associative stimulation (PAS), but turned non-focal tDCS-generated facilitatory plasticity into inhibition, and prolonged the after-effects of inhibitory plasticity-inducing procedures (Kuo et al. 2008). Here we aimed to explore systematically the dosage-dependent effects of l-dopa on neuroplasticity by comparing the impact of three different dosages of the drug on tDCS-induced plasticity. Specifically, we compared the effects of 100 mg, which has already been shown to be functionally effective, with 25, and 200 mg l-dopa. tDCS was applied to the primary motor cortex, and motor cortical excitability was monitored via motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes elicited by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which serves as an index of corticospinal excitability (Rothwell, 1993).

Methods

Ethical approval

The experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the University of Göttingen and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, who were paid for participating.

Subjects

Twelve right-handed healthy subjects participated in the experiment (5 men, 7 women, age 30.83 ± 5.10 (standard deviation) years). These received l-dopa at low, medium and high dosages (see below in Pharmacological Intervention) or placebo medication. They had no history of chronic or acute neurological, psychiatric, or medical diseases, no family history of epilepsy, no pregnancy, no cardiac pacemaker, no previous surgery involving implants to the head (cochlear implants, aneurysm clips, brain electrodes, etc.) and did not take acute or chronic medication or drugs.

Neuroplasticity induction by tDCS

We used a battery-driven constant current stimulator (Schneider Electronic, Gleichen, Germany) with a maximum output of 2 mA. tDCS was applied using a pair of saline-soaked surface sponge electrodes (35 cm2). One electrode was positioned over the motor cortex representational area of the right abductor digiti minimi (ADM) muscle, the other electrode above the right orbit. tDCS was administered with a current strength of 1 mA for 13 min (anodal tDCS, the polarity refers always to the motor cortical electrode) or 9 min (cathodal tDCS). These stimulation protocols induce cortical excitability enhancements or inhibition, which last for about 1 h after the end of stimulation (Nitsche & Paulus, 2001; Nitsche et al. 2003a).

Pharmacological interventions

Low (25 mg), medium (100 mg) or high (200 mg) dosages of l-dopa, and the decarboxylase inhibitor benserazide in a relative dosage of 1:4, or equivalent placebo (PLC) drugs were taken orally by the subjects 1 h before the start of tDCS. Approximately at this time point l-dopa reaches its maximum plasma concentration (Dingemanse et al. 1995; Djaldetti et al. 2003) and produces prominent effects in the human CNS (Flöel et al. 2005; Kuo et al. 2008). We chose 100 mg l-dopa as medium dosage because it affected tDCS-induced plasticity prominently in a former experiment (Kuo et al. 2008) and because 100 mg l-dopa has been calculated to be sufficient for completely ‘refilling’ a normal human dopaminergic system (de la Fuente-Fernández et al. 2004). Twenty-five milligrams was chosen as the lowest dosage, because it resembles a sub-therapeutic dosage roughly equivalent to the dosage of pergolide and ropinirole (Monte-Silva et al. 2009) which was shown to affect tDCS-induced plasticity in a former study (Nitsche et al. 2006). However, since pergolide (predominant D2-like dopamine agonist), ropinirole (predominant D3/D2 agonist) and l-dopa have different subreceptor affinities, and reliable detailed empirical data about the bioequivalence of the different drugs are missing, the exact dosage comparison between these drugs should be made with caution. We chose 200 mg of l-dopa as the maximum dosage, because it was the largest dosage the subjects tolerated without frequent major systemic side effects and because it was estimated to represent a threshold dose for inducing augmentation in restless legs syndrome (Paulus & Trenkwalder, 2006). To minimize peripheral l-dopa effects on the vegetative system, 40 mg domperidon, a peripheral D2 antagonist, was administered orally 1 h before l-dopa intake. After 1 h, 100 mg l-dopa results in a blood plasma level of about 1.3 ± 0.6 mg l−1 (Dingemanse et al. 1995). Each experimental session was separated by at least 1 week to avoid cumulative drug and stimulation effects.

Monitoring of motor cortical excitability

TMS-elicited motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) were recorded to monitor excitability changes of the motor cortex representation area of the right ADM. Single-pulse TMS was conducted by a Magstim 200 magnetic stimulator (Magstim Company, Whiteland, Dyfed, UK) with a figure-of-eight magnetic coil (diameter of one winding = 70 mm, peak magnetic field = 2.2 T). The coil was held tangentially to the skull, with the handle pointing backwards and laterally at an angle of 45 deg from midline, inducing a posterior–anterior current flow direction in the motor cortex. The optimal position was defined as the site where stimulation resulted consistently in the largest MEPs. Surface EMG was recorded from the right ADM with Ag–AgCl electrodes in a belly-tendon montage. The signals were amplified and filtered with a time constant of 80 ms and a low-pass filter of 2.0 kHz, then digitized at an analog-to-digital rate of 5 kHz and further relayed into a laboratory computer using the Signal software and CED 1401 hardware (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). The intensity was adjusted to elicit, on average, baseline MEPs of 1 mV peak-to-peak amplitude and was kept constant for the post-stimulation assessment unless adjusted (see below).

Experimental procedures

The experiment was conducted in a complete cross-over repeated measurement design. Subjects were blinded with regard to the specific medication, and tDCS polarity conditions. They were seated in a comfortable chair with head and arm rests. TMS was applied over the left motor cortical representational area of the right ADM where it produced consistently the largest MEPs in the resting muscle (optimal site). The intensity of the TMS stimulus was adjusted to elicit MEPs with a peak-to-peak amplitude of on average 1 mV (baseline 1). One hour after intake of l-dopa or the equivalent placebo medication, a second baseline (baseline 2) was determined to control for a possible influence of the drug on cortical excitability and adjusted if necessary (baseline 3). Afterwards motor cortical tDCS was performed. Immediately after tDCS, 25 MEPs were recorded at a frequency of 0.25 Hz every 5 min for half an hour, and then every 30 min up to 2 h after the end of each stimulation. Under l-dopa conditions, but not under PLC conditions, TMS recordings were performed at four additional time points: same day evening (SE; between 18.00 and 21.00 h), next morning (NM; between 07.00 and 10.00 h), next afternoon (NA, between 13.00 and 15.00 h), next evening (NE, between 18.00 and 21.00 h) and morning of the third day (3rd, between 07.00 and 10.00 h) The electrode and coil positions were marked with water-proof ink to guarantee identical positions during the whole course of the experiment. Under PLC conditions, the after-effects of tDCS were evaluated until 120 min after the stimulation because we did not expect longer lasting after-effects in these conditions (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Experimental course of the present study.

TMS was applied over the left motor cortical representational area of the right ADM with an intensity to elicit motor evoked potentials (MEPs) with a peak-to-peak amplitude of on average 1 mV (baseline 1: BL 1). One hour after intake of laevodopa (l-dopa), but not after placebo (PLC) medication, a second baseline (baseline 2: BL 2) was determined to control for a possible influence of the drug on cortical excitability and adjusted if necessary (baseline 3: BL 3). For tDCS, a current strength of 1 mA for 13 (anodal tDCS) or 9 min (cathodal tDCS) was applied (for more details see Methods). Immediately after tDCS, TMS-evoked MEPs were recorded to monitor the motor cortex excitability changes. For the l-dopa conditions, TMS recordings were performed up to the 3rd day after tDCS. Under PLC, the aftereffects of tDCS were evaluated until 120 min after tDCS.

Data analysis and statistics

Individual MEP amplitude means were calculated for each time bin, including baseline 1, 2 and 3 and post-stimulation time points, separately for each stimulation/medication combination. The post-intervention MEPs were normalized and are given as ratios of the pre-tDCS baseline (baseline 3). A repeated measurement analysis of variance (ANOVA) was calculated with the within subject factors time course (up to 120 after tDCS), tDCS (anodal and cathodal tDCS), drug dosage (25, 100, 200 mg of l-dopa and placebo) and the dependent variable MEP amplitude. Thus we performed a complete repeated measures analysis. Fisher LSD post hoc tests were performed to compare the MEP amplitudes before and after tDCS within each drug/tDCS combination separately for each time point to reveal tDCS-induced changes of MEP amplitudes, and to compare MEP amplitudes between PLC and the respective l-dopa conditions for all time points separately. Baseline MEP amplitudes and stimulation intensity (percentage of maximum stimulator output (MSO) were compared between conditions by Student's t test (paired samples, two-tailed, P < 0.05). All results are given as mean and standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The Mauchly test of sphericity was checked and the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was performed when necessary. Normal distribution of the data was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Results

One hour after drug intake, seven of the subjects (all women) experienced transient nausea under the highest dose of l-dopa. Vomiting occurred in three of these subjects 3–4 h after drug intake, but subsided approximately 10–15 min before the respective TMS measures. Other side-effects did not occur. The remaining subjects tolerated the drugs well.

The results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test are in accordance with a normal distribution of the MEPs. The peak-to-peak amplitude of the baseline MEPs was not significantly affected by l-dopa, i.e. MEP amplitudes did not differ before (baseline 1) and after drug intake (baseline2) in all conditions (P≥ 0.05, Student's paired, two-tailed t test; see also Table 1). A slight diminishing effect of l-dopa on cortical excitability might, however, be noticed. Stimulation intensity had to be adjusted in a minority of subjects after l-dopa intake; however percentage of MSO did not differ before and after drug intake significantly.

Table 1.

The peak-to-peak MEP amplitudes and stimulation intensity before and after application of l-dopa

| tDCS | TMS-parameters | l-Dopa | Baseline 1 | Baseline 2 | Baseline 3 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anodal | MEP | 25 mg | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | 0.087 |

| 100 mg | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.84 ± 0,08 | 1.05 ± 0.06 | 0.228 | ||

| 200 mg | 1.06 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.078 | ||

| MSO | 25 mg | 47%± 0.07 | 47%± 0.07 | 47%± 0.08 | 0.586 | |

| 100 mg | 47%± 0.07 | 47%± 0.07 | 48%± 0.08 | 0.173 | ||

| 200 mg | 46%± 0.07 | 46%± 0.07 | 46%± 0.07 | 0.137 | ||

| Cathodal | MEP | 25 mg | 1.02 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.126 |

| 100 mg | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 1.10 ± 0.08 | 0.069 | ||

| 200 mg | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 0.98 ± 0.09 | 0.99 ± 0.04 | 0.907 | ||

| MSO | 25 mg | 46%± 0.08 | 46%± 0.08 | 46%± 0.08 | 0.339 | |

| 100 mg | 47%± 0.08 | 47%± 0.08 | 48%± 0.08 | 0.090 | ||

| 200 mg | 47%± 0.08 | 47%± 0.08 | 47%± 0.08 | 0.070 |

Shown are the mean MEP amplitudes ± s.e.m. and stimulation intensity (percentage of maximum stimulator output, MSO) mean ± SD (standard deviation) of baselines 1 and 2. The intensity of TMS was adjusted to elicit MEPs with a peak-to-peak amplitude of on average 1 mV (baseline 1). One hour after intake of l-dopa (25, 100 and 200 mg) a second baseline (baseline 2) was determined to control for an influence of the drug on cortical excitability and adjusted if necessary (baseline 3). MEP amplitudes and percentage of MSO did not differ significantly before and after drug intake in all conditions (P ≥ 0.05, Student's paired, two-tailed t test).

Dose-dependent effect of l-dopa on tDCS-induced plasticity

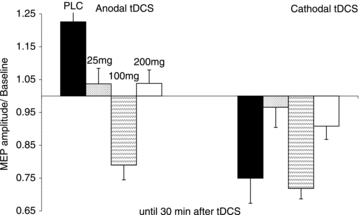

The ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of time course × tDCS × dosage (Table 2). Under placebo medication, anodal and cathodal tDCS significantly increased or decreased, respectively, cortical excitability until 1 h after the end of stimulation (Fig. 2). As revealed by the post hoc t tests, under 25 and 200 mg of l-dopa the excitatory and inhibitory effects of tDCS on cortical excitability were suppressed and differed significantly from the placebo medication condition (Fig. 2A and C). Compared with baseline MEPs, as revealed by the post hoc tests, under medium dosage l-dopa (100 mg) anodal tDCS resulted in a significant excitability reduction, which lasted up to the next evening after DC stimulation. Similarly, the cathodal tDCS-elicited neuroplastic excitability reduction was significantly prolonged until the evening 1 day after tDCS, as compared to baseline MEPs. A respective trend should also be noted in relation to the MEP size under PLC medication 120 min after tDCS (Fig. 2B). In summary, l-dopa dose-dependently modified the tDCS-induced plastic excitability changes: whereas low (25 mg) and high (200 mg) dosages of l-dopa impaired both cathodal and anodal tDCS-induced neuroplasticity, as compared to PLC conditions, the medium dosage converted the anodal tDCS-induced MEP alterations into inhibition, and prolonged the cathodal tDCS-generated changes (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Results of the ANOVA

| d.f. | F value | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Time course | 10 | 2.078 | 0.033* |

| tDCS | 1 | 43.516 | <0.001* | |

| Dosage | 3 | 19.206 | <0.001* | |

| Time course × tDCS | 10 | 3.626 | <0.001* | |

| Time course × dosage | 6.7 | 1.445 | 0.205 | |

| tDCS × dosage | 3 | 14.632 | <0.001* | |

| Time course × tDCS × dosage | 6.3 | 2.495 | <0.029* |

The ANOVA encompasses the time course for up to 120 min after stimulation, because the remaining time points were only measured for the l-dopa conditions. Asterisks indicate significant results (P ≤ 0.05), d.f.: degrees of freedom.

Figure 2. Dose-dependent effect of l-dopa on neuroplasticity induced by anodal and cathodal tDCS.

The time course plots show the effect of different doses of l-dopa on tDCS-induced neuroplasticity. Shown are baseline-standardized motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes after plasticity induction by cathodal and anodal tDCS under 25, 100 and 200 mg of l-dopa or PLC up to the morning 2 days after tDCS. As shown by the TMS-elicited MEP amplitudes, l-dopa produced a biphasic response, where low (25 mg) and high (200 mg) dosages impaired both cathodal and anodal tDCS-induced neuroplasticity, as compared to the placebo (PLC) condition. Under medium dosage (100 mg), l-dopa reverses the anodal tDCS-elicited neuroplastic excitability enhancement into inhibition. This inhibitory effect lasted until the evening after stimulation. A long-lasting inhibition was also observed in the cathodal tDCS condition under l-dopa. Shown are the mean ±s.e.m. MEP amplitudes vs. baseline across time following anodal or cathodal tDCS for 25 mg (A), 100 mg (B) and 200 mg (C) l-dopa and PLC conditions. Filled symbols indicate significant deviations of the post-tDCS MEP amplitudes from baseline values; #significant deviations of drug vs. PLC conditions with regard to identical time points and tDCS polarities (Fisher's LSD). 3rd: 3rd day (between 07.00 and 10.00 h); NE: next evening (between 18.00 and 21.00 h); NM: next morning (between 07.00 and 10.00 h); NA: next afternoon (between 13.00 and 15.00 h); SE: same evening (between 18.00 and 21.00 h).

Figure 3. Dose-dependent effect of l-dopa on NMDA receptor-dependent excitability changes in the human motor cortex.

l-Dopa exerts a non-linear effect on neuroplasticity induced by tDCS. High and low dosages impaired plasticity. Each column represents the mean of baseline-standardized MEP amplitudes ±s.e.m. until 30 min after stimulation.

Discussion

The results of the present study show a non-linear dosage–effect relation of dopamine receptor activation on neuroplasticity: low or excessive dopamine levels impaired the establishment of tDCS-induced plasticity, independent from stimulation polarity, while under the medium dosage of the drug the inhibitory after-effects of cathodal tDCS lasted more than 24 h after stimulation and the effects of anodal tDCS were converted from facilitation into inhibition. For the medium dosage, this result is in accordance with that of a former study (Kuo et al. 2008).

Mechanisms underlying the nonlinear dose-dependent effect of l-dopa on tDCS-induced plasticity

The effect of DA on neuronal activity, excitability and plasticity is complex and affected by many different factors, such as DA subreceptors, cortical area, level of spontaneous cortical activity, and basal dopaminergic level, amongst others (Seamans & Yang, 2004). Thus any explanation of the results is necessarily somewhat hypothetical at present, given the limited knowledge about the specific action of DA with regard to these factors in humans. However, together with the results of former studies, we propose the following mechanism of action.

Since tDCS-induced plasticity seems to depend on alterations of intraneuronal calcium concentration (Nitsche et al. 2003b), and it is known from animal experiments that dependent on calcium concentration, LTP, LTD or no plasticity is induced (Lisman, 2001), we propose that DA exerts its plasticity-modulating action by affecting tDCS-induced calcium influx via modulation of NMDA receptor-dependent excitation and GABAergic inhibition (for an overview of the effects of DA on these receptors, see Seamans & Yang, 2004). Without any medication, we suggest that DA is necessary to elevate tDCS-affected calcium concentration to a level that induces LTP- or LTD-like excitability alterations. Calcium concentration will be enhanced by the NMDA receptor-enhancing activity of D1 receptors, and the weakening of GABAergic inhibition by postsynaptic D2 receptors (Chen & Yang, 2002). In accordance, plasticity was abolished in patients with Parkinson's disease off medication, but re-established by dopaminergic agents (Morgante et al. 2006; Ueki et al. 2006), and application of the D2 receptor antagonist sulpiride abolished tDCS-induced plasticity in healthy subjects (Nitsche et al. 2006). For low-dosage DA it is important to realize that DA dose-dependently binds preferentially to pre- or postsynaptic receptors. Low doses of the DA agonist apomorphine preferentially activate presynaptic D2-like receptors, which reduce the firing rate, synthesis and release of DA, whereas higher doses stimulate postsynaptic receptors (Yamada & Furukawa, 1980). Therefore, probably low-dosage l-dopa affected primarily pre-synaptic DA autoreceptors, and in this way lowered DA concentration, and therefore calcium influx to a level that prevents plasticity induction.

For the medium dosage of l-dopa, the above-mentioned effects of D1- and D2-like postsynaptic receptors on calcium influx are assumed to be enhanced. For the anodal tDCS condition, further NMDA receptor activity enhancement, and GABAergic reduction, both induced by D1 and D2 receptors, might enhance calcium concentration to a level which activates hyperpolarizing potassium channels (Misonou et al. 2004), thus resulting in inhibitory plasticity. For cathodal tDCS, the same dopaminergic mechanisms might enhance the minor cathodal tDCS-induced enhancement of calcium concentration to a level optimizing LTD-like plasticity induction, which would explain the prolonged after-effects of cathodal tDCS in this condition. Thus for explaining the effects of l-dopa on tDCS-induced plasticity here, combined activation of D1 and D2 receptors is needed.

This proposed mechanism of action is also compatible with the effects of medium D1- or D2-like receptor activation, which both resulted in a re-establishement of facilitatory and inhibitory tDCS-induced plasticity, but no prolongation of the after-effects (Monte-Silva et al. 2009; Nitsche et al. 2009).

For high-dosage l-dopa, it is important that D1 receptors as well as D2 receptors inhibit NMDA receptor activity at larger dosages (Castro et al. 1999; Chen & Yang, 2002; Kotecha et al. 2002). Therefore, high activation of both receptors might counteract the calcium-increasing properties of tDCS and thus prevent plasticity induction. A similar effect has been demonstrated for the D2-like agonist ropinirole (Monte-Silva et al. 2009).

In further accordance, a recently published study demonstrated that the ability of a specific stimulation protocol to elicit LTP in animal slice preparations depended on the level of dopaminergic background activity. Low and high activation of the dopaminergic system abolished plasticity, whereas a medium concentration enhanced it. This effect afforded simultaneous D1 and D2 receptor activation and was mediated by ERK activation (Kolomiets et al. 2009). Future studies should explore the supposed above-mentioned mechanisms more directly, e.g. exploring the effect of partial calcium channel block on the modulatory effect of l-dopa on tDCS-induced plasticity.

It should be stressed that this model of dopaminergic effects on plasticity is speculative at present. Future studies should encompass the exploration of the mechanisms of action of dopaminergic alterations of plasticity in humans in larger detail. Co-application of calcium channel antagonists might be able to prove the above-mentioned hypotheses. It should also be kept in mind that the comparison of different dopaminergic agents with regard to the efficacy to bind to DA subreceptors dose-dependently is a so far not completely solved problem, making exact comparisons between different substances difficult.

Some other potentially limiting aspects of the study and the interpretation of the results should be mentioned: (a) l-dopa alone did not modulate MEPs significantly, but a trend for a reduction of MEPs obtained after, as compared to before drug administration, is present. Such an effect, which might have become significant with more subjects studied, has been shown before, and might be caused by D1 receptor activation (Nitsche et al. 2009). In our opinion it is however improbable that this small effect on acute cortical excitability has affected the results relevantly, because the plasticity effects were much larger, and longer-lasting than the half-life of l-dopa. (b) Subject blinding might have been somewhat compromised because of the different duration of monitoring of the after-effects and systemic side-effects of l-dopa in the different experimental sessions. However, because (i) the multitude of sessions per subject makes it difficult to identify the specific experimental condition with regard to stimulation and drug condition, and (ii) the participants were not aware of the proposed results, we believe that blinding was not relevantly affected. Moreover the l-dopa pills were different in shape between all conditions, and thus it is difficult to imagine that participants could identify them. (c) Three of the subjects vomited after drug intake, and thus one could speculate that this might have impaired drug resorption. However, since vomiting occurred 3–4 h after drug intake, we assume that gastrointestinal resorption of l-dopa should have been complete at this time point, and thus did not exclude the respective subjects from further analysis. An additional analysis shows moreover that the results of the experiments were not altered when these subjects were excluded from the calculations (see online Supplemental Material, Fig. 1). (d) The absence of equivalent PLC measures at the SE, NM, NA, NE and 3rd time points makes statements about the prolongation of the cathodal tDCS-induced excitability diminution by the medium dosage of l-dopa somewhat weaker, because it precludes a direct comparison of MEPs for these time points. However, since the tDCS-induced effects were still significant until the next evening after tDCS, when compared with baseline MEPs, we presume that the 100 mg dose of l-dopa prolonged the tDCS effect relevantly, because it was shown in numerous studies that the effects of cathodal tDCS alone do not last longer than about 1 h (Kuo et al. 2007, 2008; Monte-Silva et al. 2009; Nitsche et al. 2003a, 2004a,b).

General remarks

In the present study we aimed to investigate how different dosages of l-dopa affect the induction of neuroplasticity in the human motor cortex. In summary, our study shows a non-linear effect of the drug on plasticity. The effects differ partially from those accomplished with D2-like or D1-like activation, and might be caused by a synergistic interaction between both receptor subtypes.

Since learning and memory formation are thought to be related to LTP-like plasticity, and LTP-like plasticity induced by tDCS was abolished or converted into inhibition in this study, how comes it that l-dopa improves the respective cognitive processes in humans (Knecht et al. 2004; Flöel et al. 2005)? In this context it is important that l-dopa affects non-focal (as induced by tDCS) and focal facilitatory plasticity (as generated by PAS) differently: PAS-induced facilitatory plasticity was enhanced by medium-dosed l-dopa in a prior study (Kuo et al. 2008). This pattern of results favours a focusing effect of DA on plasticity, which might improve cognitive performance, where only task-relevant synaptic connections should be modified. Since this effect is dosage dependent (unpublished results of our group show an abolition of PAS-induced plasticity under low and high dosages of l-dopa, similar to its effect on tDCS), it might be an interesting question for future studies if a similar dosage dependency applies for learning and memory formation in humans. However, it is important to keep in mind that beyond focality of stimulation, PAS and tDCS differ also with regard to other factors, which might be relevant for the results. Whereas PAS induces temporally and spatially associated cortical action potentials, tDCS alters spontaneous non-associative neuronal activity by subthreshold modulation of resting membrane potentials. Moreover, tDCS and PAS might affect different neuronal pools.

Moreover, this non-linear effect of l-dopa on plasticity might explain at least partially seemingly opposing results for dopaminergic alteration of learning and memory formation, e.g. in stroke patients (Liepert, 2008), because the efficacy of dopaminergic enhancement to improve function might depend on the specific level of dopaminergic activation. This will depend on drug dosage as well as basal dopaminergic activity, which might differ relevantly between patients. For restless legs syndrome, the non-linear dose dependency of l-dopa effects on cortical functions might explain why relatively low dosages reduce, but larger dosages of dopaminergic medication worsen symptoms. On the more basic research level, the dosage dependency of the effect of dopaminergic activation might help to explain why these drugs enhance plasticity in some studies, but reduce or convert it in others (for an overview see Seamans & Yang, 2004).

Some further interesting aspects for future studies should be mentioned. (a) The impact of dopaminergic drugs on cognition is age dependent. Increased age reduces dopaminergic signalling, and receptor density (Volkow et al. 1994; Flöel et al. 2008). Thus, the effect of dopamine on plasticity, as accomplished in the present study, might be specific for young healthy subjects, and differ in older subjects. (b) It should be kept in mind that in the present study, all DA dosages induced a somewhat ‘hyperdopaminergic state’ in healthy subjects, limiting, therefore, the extrapolation of results to patients with a dopaminergic deficit. Since the pharmacodynamic effects of l-dopa have been shown to be correlated with plasma concentrations (Khor & Hsu, 2007), measures of dopamine plasma level in future studies would help with the interpretation of the data. Thus, for obtaining therapeutic information, further studies are needed to explore directly if the non-linear effect of dopamine on cortical function is the same in patients as in the healthy subjects studied here. (c) Genetic factors influence stimulation-induced plasticity in humans (Cheeran et al. 2008). Thus it is possible that individual genetic variants may affect the specific impact of dopaminergic activity on plasticity, as shown for the COMT polymorphism and working memory performance under amphetamine (Mattay et al. 2003). tDCS, along with other non-invasive brain stimulation protocols, is increasingly used for therapeutic purposes in neuropsychiatric diseases. The non-linear impact of l-dopa on tDCS-induced plasticity in this study points to the fact that it might be important in future therapeutic stimulation studies to explore the physiological effect of brain stimulation protocols in the disease under study first, and to take into account central nervous acting medication as an important factor, because the effects of stimulation on cortical excitability might categorically differ dependent on the concentration of neuromodulators in the human brain.

Acknowledgments

M.-S. is supported by CAPES, Brazil. This project was further supported by the DFG, grant NI 683/6-1.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADM

abductor digiti minimi

- DA

dopamine

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MEP

motor evoked potential

- PAS

paired associative stimulation

- PLC

placebo

- tDCS

transcranial direct current stimulation

- TMS

transcranial magnetic stimulation

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave their final approval of the version to be published. The experiments were conducted at the Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Georg-August-University, Göttingen, Germany.

Supplemental material

Figure 1

Table 1

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors

References

- Bertolino A, Fazio L, Giorgio A, Blasi G, Romano R, Taurisano P, Caforio G, Sinibaldi L, Ursini G, Popolizio T, Tirotta E, Papp A, Dallapiccola B, Borrelli E, Sadee W. Genetically determined interaction between the dopamine transporter and the D2 receptor on prefronto-striatal activity and volume in humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1224–1234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4858-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai JX, Arnsten AF. Dose-dependent effects of the dopamine D1 receptor agonists A77636 or SKF81297 on spatial working memory in aged monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Picconi B, Tozzi A, Filippo Di. Dopamine-mediated regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro NG, de Mello MC, de Mello FG, Aracava Y. Direct inhibition of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor channel by dopamine and (+)-SKF38393. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1847–1855. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeran B, Talelli P, Mori F, Koch G, Suppa A, Edwards M, Houlden H, Bhatia K, Greenwood R, Rothwell JC. A common polymorphism in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene (BDNF) modulates human cortical plasticity and the response to rTMS. J Physiol. 2008;586:5717–5725. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.159905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Yang CR. Interaction of dopamine D1 and NMDA receptors mediates acute clozapine potentiation of glutamate EPSPs in rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2324–2336. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Fernández R, Sossi V, Huang Z, Furtado S, Lu JQ, Calne DB, Ruth TJ, Stoessl AJ. Levodopa-induced changes in synaptic dopamine levels increase with progression of Parkinson's disease: implications for dyskinesias. Brain. 2004;127:2747–2754. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemanse J, Jorga K, Zürcher G, Schmitt M, Sedek G, Da Prada M, Van Brummelen P. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic interaction between the COMT inhibitor tolcapone and single-dose levodopa. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40:253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djaldetti R, Giladi N, Hassin-Baer S, Shabtai H, Melamed E. Pharmacokinetics of etilevodopa compared to levodopa in patient's with Parkinson's disease: an open-label, randomized, crossover study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:322–326. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200311000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flöel A, Breitenstein C, Hummel F, Celnik P, Gingert C, Sawaki L, Knecht S, Cohen LG. Dopaminergic influences on formation of a motor memory. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:121–130. doi: 10.1002/ana.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flöel A, Vomhof P, Lorenzen A, Roesser N, Breitenstein C, Knecht S. Levodopa improves skilled hand functions in the elderly. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:1301–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Muly EC, 3rd, Williams GV. D1 receptors in prefrontal cells and circuits. Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N, Aftabuddin M, Moriwaki A, Hattori Y, Hori Y. Increase in the calcium level following anodal polarization in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1995;684:206–208. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00434-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khor SP, Hsu A. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2007;2:234–243. doi: 10.2174/157488407781668802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht S, Breitenstein C, Bushuven S, Wailke S, Kamping S, Floel A, Zwitserlood P, Ringelstein EB. Levodopa: faster and better word learning in normal humans. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:20–26. doi: 10.1002/ana.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomiets B, Marzo A, Caboche J, Vanhoutte P, Otani S. Background dopamine concentration dependently facilitates long-term potentiation in rat prefrontal cortex through postsynaptic activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2708–2718. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotecha SA, Oak JN, Jackson MF, Perez Y, Orser BA, Van Tol HHM, MacDonald JF. A D2 class dopamine receptor transactivates a receptor tyrosine kinase to inhibit NMDA receptor transmission. Neuron. 2002;35:1111–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung VW, Hassam R, Morton AJ, Jones S. Dopamine-dependent long term potentiation in the dorsal striatum is reduced in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington's disease. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1571–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MF, Grosch J, Fregni F, Paulus W, Nitsche MA. Focusing effect of acetylcholine on neuroplasticity in the human motor cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14442–14447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4104-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MF, Paulus W, Nitsche MA. Boosting focally-induced brain plasticity by dopamine. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:648–651. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang N, Speck S, Harms J, Rothkegel H, Paulus W, Sommer M. Dopaminergic potentiation of rTMS-induced motor cortex inhibition. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:231–233. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebetanz D, Nitsche MA, Tergau F, Paulus W. Pharmacological approach to the mechanisms of transcranial DC-stimulation-induced after-effects of human motor cortex excitability. Brain. 2002;125:2238–2247. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepert J. Pharmacotherapy in restorative neurology. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:639–643. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32831897a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE. Three Ca2+ levels affect plasticity differently: the LTP zone, the LTD zone and no man's land. J Physiol. 2001;532:285. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0285f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattay VS, Goldberg TE, Fera F, Hariri AR, Tessitore A, Egan MF, Kolachana B, Callicott JH, Weinberger DR. Catechol O-methyltransferase val158-met genotype and individual variation in the brain response to amphetamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6186–6191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931309100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misonou H, Mohapatra DP, Park EW, Leung V, Zhen D, Misonou K, Anderson AE, Trimmer JS. Regulation of ion channel localization and phosphorylation by neuronal activity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:711–718. doi: 10.1038/nn1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgante F, Espay AJ, Gunraj C, Lang AE, Chen R. Motor cortex plasticity in Parkinson's disease and levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Brain. 2006;129:1059–1069. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte-Silva K, Kuo M, Thirugnanasambandam N, Liebetanz D, Paulus Walter, Nitsche MA. Dose-dependent inverted U-shaped effect of dopamine (D2-like) receptor activation on focal and non-focal plasticity in humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6124–6131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0728-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Fricke K, Henschke U, Schlitterlau A, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Henning S, Tergau F, Paulus W. Pharmacological modulation of cortical excitability shifts induced by transcranial direct current stimulation in humans. J Physiol. 2003b;553:293–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Grundey J, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Tergau F, Paulus W. Catecholaminergic consolidation of motor cortical neuroplasticity in humans. Cerebral Cortex. 2004a;14:1240–1245. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Jaussi W, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Tergau F, Paulus W. Consolidation of human motor cortical neuroplasticity by D-cycloserine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004b;29:1573–1578. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology. 2001;57:1899–1901. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Nitsche MS, Klein CC, Tergau F, Rothwell JC, Paulus W. Level of action of cathodal DC polarisation induced inhibition of the human motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003a;114:600–604. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Lampe C, Antal A, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Tergau F, Paulus W. Dopaminergic modulation of long-lasting direct current induced cortical excitability changes in the human motor cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1651–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Cohen LG, Wassermann EM, Priori A, Lang N, Antal A, Paulus W, Hummel F, Boggio PS, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial direct current stimulation: state of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 2008;1:206–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Kuo MF, Grosch J, Bergner C, Monte-Silva K, Paulus W. D1-receptor impact on neuroplasticity in humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2648–2653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5366-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Carroll CM, Martin SJ, Sandin J, Frenguelli B, Morris RG. Dopaminergic modulation of the persistence of one-trial hippocampus-dependent memory. Learn Mem. 2006;13:760–769. doi: 10.1101/lm.321006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus W, Trenkwalder C. Less is more: pathophysiology of dopaminergic-therapy-related augmentation in restless legs syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:878–886. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70576-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell JC. Evoked potentials, magnetic stimulation studies, and event-related potentials. Curr Opin Neurol. 1993;6:715–723. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamans JK, Yang CR. The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki Y, Mima T, Kotb MA, Sawada H, Saiki H, Ikeda A, Begum T, Reza F, Nagamine T, Fukuyama H. Altered plasticity of the human motor cortex in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:60–71. doi: 10.1002/ana.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Schlyer D, Hitzemann R, Lieberman J, Angrist B, Pappas N, MacGregor R, Burr G, Cooper T, Wolf AP. Imaging endogenous dopamine competition with [11C]raclopride in the human brain. Synapse. 1994;16:255–262. doi: 10.1002/syn.890160402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Furukawa T. Direct evidence for involvement of dopaminergic inhibition and cholinergic activation in yawning. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1980;67:39–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00427593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GV, Castner SA. Under the curve: critical issues for elucidating D1 receptor function in working memory. Neuroscience. 2006;139:263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.