Abstract

A challenge for photobiological production of hydrogen gas (H2) as a potential biofuel is to find suitable electron-donating feedstocks. Here, we examined the inorganic compound thiosulfate as a possible electron donor for nitrogenase-catalyzed H2 production by the purple nonsulfur phototrophic bacterium (PNSB) Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Thiosulfate is an intermediate of microbial sulfur metabolism in nature and is also generated in industrial processes. We found that R. palustris grew photoautotrophically with thiosulfate and bicarbonate and produced H2 when nitrogen gas was the sole nitrogen source (nitrogen-fixing conditions). In addition, illuminated nongrowing R. palustris cells converted about 80% of available electrons from thiosulfate to H2. H2 production with acetate and succinate as electron donors was less efficient (40 to 60%), partly because nongrowing cells excreted the intermediary metabolite α-ketoglutarate into the culture medium. The fixABCX operon (RPA4602 to RPA4605) encoding a predicted electron-transfer complex is necessary for growth using thiosulfate under nitrogen-fixing conditions and may serve as a point of engineering to control rates of H2 production. The possibility to use thiosulfate expands the range of electron-donating compounds for H2 production by PNSBs beyond biomass-based electron donors.

Hydrogen gas (H2) is a potential alternative to gasoline for use as a transportation fuel in conjunction with hydrogen fuel cells because it has a high energy content, yields water as a combustion product, and can be produced in a variety of ways, including by steam reformation of natural gas, by electrolysis, or biologically. Photobiological methods to produce H2 are less energy intensive than conventional methods and are theoretically sustainable (10). Oxygenic phototrophs, including algae and cyanobacteria, have excellent potential for H2 production because they can use electrons derived from water along with solar energy to drive the process (10, 24). However, the amount of H2 that is naturally produced by these microbes is severely compromised by the oxygen sensitivity of the hydrogenases and nitrogenases that catalyze H2 production. Anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria, including purple nonsulfur phototrophic bacteria (PNSBs), are not subject to problems of oxygen sensitivity during H2 production, but they are limited in that they must use electron donors that are much more restricted in abundance than water (10, 12, 24). In studies with PNSBs, organic compounds are typically provided as the source of electrons to combine with protons to generate hydrogen (1, 8, 12, 28).

Rhodopseudomonas palustris is a PNSB that is attractive for development as a biocatalyst for H2 production because it has a versatile metabolism, is robust, and does not generate oxygen in combination with H2 (20, 27). H2 production is catalyzed by nitrogenase, an enzyme that produces H2 along with ammonia (NH3) as an obligate aspect of its catalytic cycle (33). In the absence of N2, nitrogenase activity converts reductant and energy to H2 exclusively (14). R. palustris has three functional nitrogenase isoenzymes, but it uses Mo nitrogenase under most growth conditions (28). It generates the large amounts of ATP required for nitrogenase activity by photophosphorylation from solar energy and can obtain the electrons needed for H2 from the metabolism of a variety of carbon compounds, including lignin monomers (8, 30).

In this study, we examined the use of the inorganic compound thiosulfate as an electron donor for H2 production by R. palustris strain CGA009. R. palustris has been shown to grow photoautotrophically with thiosulfate as an electron source and bicarbonate as a carbon source (22, 31, 32). The genomes of strain CGA009 and other Rhodopseudomonas strains have homologs of the well-characterized sox gene cluster of Paracoccus pantotrophus, which encodes a multiprotein complex that oxidizes thiosulfate to sulfate within the periplasm (20, 25, 27). Thiosulfate is present in nature as an intermediate of the sulfur cycle from the biological oxidation of sulfur compounds (4, 15, 16, 21, 37) and is also formed abiotically as a product of kraft paper manufacturing and during the removal of sulfide from contaminated natural gas streams (26, 34).

Here we show that R. palustris grows photoautotrophically with thiosulfate and bicarbonate and produces H2 when N2 is supplied as a sole nitrogen source (nitrogen-fixing conditions). We also found that cells grown under nitrogen-fixing conditions followed by suspension in buffer in a nongrowing state transferred electrons from thiosulfate to H2 with high efficiency relative to the efficiency achieved with organic compounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

R. palustris wild-type strain CGA009 (20), its nifA* derivative, strain CGA584 (30), and fixC and fixX mutants derived from strain CGA009 were grown anaerobically in a defined mineral medium (10 ml) in sealed 27-ml culture tubes (Bellco, Vineland, NJ) with ammonium sulfate as the nitrogen source (PM medium) or without ammonium sulfate for growth under nitrogen-fixing conditions (NFM medium) (18). The headspace of the culture tubes contained N2. For photoautotrophic growth, cultures were grown with 0.1 to 6 mM thiosulfate as the electron donor and 20 mM bicarbonate as the carbon source. For photoheterotrophic growth, cells were grown with 4 mM succinate or acetate unless otherwise indicated. Cultures were grown phototrophically at 30°C with illumination from 60-W incandescent light bulbs. Antibiotic concentrations used for R. palustris were 100 μg gentamicin (Gm)/ml and 100 μg kanamycin/ml, and the antibiotic concentration used for Escherichia coli was 20 μg Gm/ml. Cultures were transferred and manipulated in an anaerobic glove box (Coy Laboratories, Grass Lake, MI).

Preparation of nongrowing cell suspensions.

Nongrowing R. palustris cell suspensions were prepared as follows. Cells were first grown under nitrogen-fixing conditions in 80 ml of NFM medium in 160-ml serum bottles with 4 mM (each) thiosulfate, acetate, and succinate and 10 mM sodium bicarbonate with an N2 headspace. Cultures in midgrowth at an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 0.7 were harvested by centrifuging at 4,000 rpm for 8 min. The cells were moved to an anaerobic chamber and washed once with 1 volume of deaerated 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The suspended cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in 2 volumes (160 ml) of deaerated phosphate buffer and incubated in light in sealed serum bottles with an Ar headspace for 12 h. After the incubation, electron donor was added to the cells and 10 ml of the cell suspensions (containing 0.5 to 0.6 mg total protein) was aliquoted to 27-ml sealed culture tubes with an Ar headspace. The amounts of electron donor used and H2 produced by cells were measured. During the period of incubation under nongrowing conditions, cell cultures showed changes in optical density at 660 nm that were less than 0.1.

Analytical methods.

H2 was quantified using a Hewlett-Packard 5890 series II gas chromatograph (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector and a 60/80 molecular sieve 5A column (6 ft by 1/8 in.; Sigma-Aldrich). Ar was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 35 ml/min. The oven temperature was 60°C, the inlet temperature was 150°C, and the detector temperature was 200°C. The Bio-Rad protein assay (Hercules, CA) was used to quantify cell protein concentrations. Organic acids and culture supernatants were analyzed using a Varian (Palo Alto, CA) ProStar high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a UV detector at 210 nm. Metabolites were separated at 22°C on an Aminex HPX-87H column (300 by 7.8 mm; Bio-Rad) using 4 mM H2SO4 as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. α-Ketoglutarate was positively identified by comparison to standards and enzymatically by following its conversion to glutamate and NAD+ following addition of glutamate dehydrogenase, ammonia, and NADH (2). Thiosulfate was quantified from absorbance of cell-free culture fluids at 214 nm using a Beckman Coulter DU800 spectrophotometer (Fullerton, CA). Thiosulfate concentrations were determined on the basis of a standard curve, and the limit of detection was 500 pmol. Sulfate was measured as a product of thiosulfate oxidation using the barium sulfate turbidity method (17). Using this method, it was possible to get only a qualitative measure of the sulfate generated.

Construction and complementation of R. palustris fix mutants.

In-frame deletion mutants of fixC (a nucleotide sequence corresponding to 429 of the 435 amino acids of the predicted protein was deleted) and fixX (a nucleotide sequence corresponding to 89 of the 98 amino acids of the predicted protein was deleted) were constructed as follows. DNA fragments (∼1 kb each) spanning the two flanking regions of the deletion site were generated by PCR. Each DNA fragment contained an engineered XbaI site at one end and a region that base paired with the other fragment during a subsequent PCR to create a (∼2-kb) deletion construct. These products were digested with XbaI and cloned into XbaI-digested pJQ200SK. This construct was mobilized from E. coli S17-1 into R. palustris CGA009 by conjugation. Colonies that contained plasmids that had undergone a single recombination to become inserted into the chromosome were identified by growth on PM medium plus Gm. Strains that had undergone a double recombination, resulting in loss of the vector and insertion of a deletion mutation, were selected and verified as described previously (30). The mutant strains were complemented with a plasmid containing the fix gene cluster expressed constitutively from the lac promoter of plasmid pBBR1 MCS-5 (19). The primers FixA_F (AAAGGTACCCAAGTGTCGGAGTTGTCGGATTG) and FixX_R (AAATCTAGATCAGCCGAACTTGAACAGCACGC) (the underlines in the two sequences represent KpnI and XbaI restriction sites, respectively) were used to amplify the fix gene cluster (RPA4602 to RPA4605) from R. palustris CGA009 using PCR with an Expand high-fidelity system and buffer 3 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The product was digested with the restriction enzymes KpnI and XbaI and ligated into the multicloning site of plasmid pBBR1MCS-5 to form plasmid pfix. pfix or the empty vector (pBBR1MCS-5) was transformed into the ΔfixC and ΔfixX mutants by electroporation (29).

RESULTS

R. palustris grows photoautotrophically with thiosulfate under nitrogen-fixing conditions.

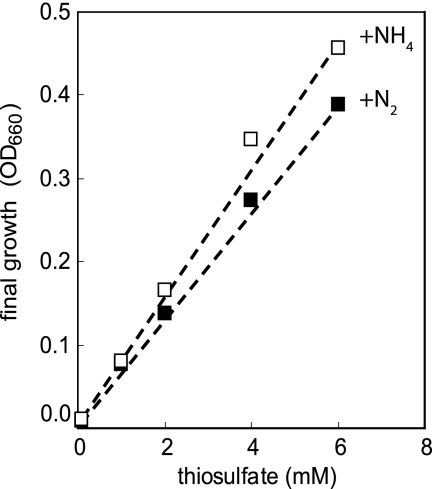

Thiosulfate and sodium bicarbonate (bicarbonate), supplied as the electron donor and carbon source, respectively, supported the growth of R. palustris when either ammonium or N2 was supplied as a source of nitrogen. Sulfate was produced as a product of thiosulfate oxidation. Cell yields were dependent on the amount of thiosulfate provided, and cultures grown with ammonium had 30% greater cell yields than cultures grown under nitrogen-fixing conditions (Fig. 1). This was expected, since under nitrogen-fixing conditions some thiosulfate is directed to ammonia and H2 production according to the equation S2O32− + 5H2O + N2 + 16ATP → 2SO42− + 2H+ + 2NH3 + H2 + 16ADP.

FIG. 1.

R. palustris growth yields on thiosulfate. The final growth of R. palustris strain CGA009 with different concentrations of thiosulfate was measured when cells reached stationary phase and the OD values of the cultures no longer increased. This period of time was from 3 days to 7 days, depending on the concentration of thiosulfate. Cultures were grown anaerobically with 20 mM bicarbonate and 0.1 to 6 mM thiosulfate either under nitrogen-replete conditions with 4 mM ammonium sulfate as the nitrogen source (open squares) or under nitrogen-fixing conditions with nitrogen gas (filled squares). The data points represent the averages of experiments that were carried out at least twice. The standard deviations between replicates for each yield were less than an OD660 of 0.02.

Cells grew with 2 mM thiosulfate and 20 mM bicarbonate with a generation time of 41.5 ± 1.4 h under nitrogen-fixing conditions. Cells were sensitive to concentrations of thiosulfate above 4 mM and grew considerably more slowly, as has been reported previously (22). The pH of the media did not change during the course of the growth experiments.

R. palustris fix mutants are defective for growth on thiosulfate under nitrogen-fixing conditions.

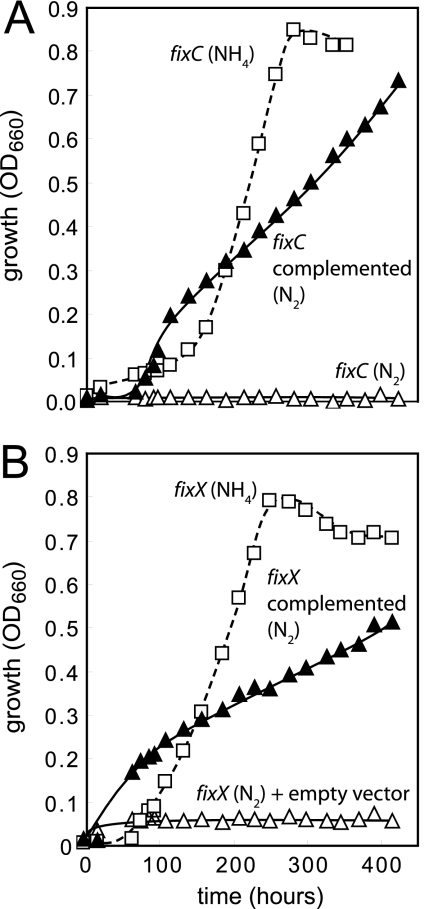

R. palustris has a fixABCX gene cluster preceding its nitrogen fixation genes. Homologous genes in Rhodospirillum rubrum encode a protein complex that is responsible for electron transfer from NADH to nitrogenase. FixAB is a predicted electron transfer factor, and FixCX resembles an electron transfer flavoprotein-quinone reductase (6, 7, 13). To test the involvement of these genes in R. palustris nitrogen fixation, we constructed fixC and fixX deletion mutants. Both mutants were unable to grow with thiosulfate under nitrogen-fixing conditions but grew as well as the wild-type parent when ammonium was the nitrogen source (Fig. 2). Introduction of the fix gene cluster on a plasmid in trans enabled the fixC and fixX mutants to grow on thiosulfate under nitrogen-fixing conditions (Fig. 2). These mutants also failed to grow with succinate under nitrogen-fixing conditions (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

R. palustris fixC and fixX mutants are unable to grow under nitrogen-fixing conditions. A fixC deletion mutant (A) and a fixX deletion mutant (B) were grown with 10 mM thiosulfate and 20 mM bicarbonate in the presence or absence of fixed nitrogen. The mutants were incubated with thiosulfate under nitrogen-fixing conditions (open triangles). In the case of the fixX mutant, we show the growth curve for cells carrying an empty vector and incubated with Gm. The growth curve for the fixX mutant with no vector is essentially the same (data not shown). The growth defect of the fixC and fixX mutants was complemented with the plasmid pfix, in which the fix gene cluster is constitutively expressed (filled triangles). Both mutants grew with thiosulfate in the presence of ammonium (open squares). The growth curves were repeated at least three times, and one representative is shown.

Substrate conversion efficiencies and H2 yields by nongrowing cells.

We determined the H2 yields and efficiencies of conversion of electrons from electron donor to H2 for R. palustris wild-type and nifA* mutant cells (NifA* strain) that were grown under nitrogen-fixing conditions and then washed and incubated in light in phosphate buffer (nongrowing conditions) in an atmosphere of Ar (Table 1). The nifA* mutant, strain CGA584, expresses its Mo nitrogenase genes constitutively at higher levels than its CGA009 parent (30). Wild-type cells converted up to 79% of the electrons from thiosulfate to H2, but only when 0.5 mM bicarbonate was also included in the incubation buffer. Increased amounts of bicarbonate did not have a further stimulatory effect. The nifA* strain, on the other hand, had efficiencies of 86% conversion of thiosulfate to H2 in the absence of bicarbonate, and addition of bicarbonate did not stimulate H2 production (Table 1). Equimolar amounts of carbon provided in the form of acetate did not stimulate rates of production or yields of H2 produced from thiosulfate by the wild type (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

H2 production by nongrowing R. palustris cells using thiosulfate or organic acids as electrons donors

| Strain | Electron donor (20 μmol) | Bicarbonate concn (mM) | Amt (μmol)a |

% electron donor oxidizeda | H2 yield (% of theoretical maximum)a,b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrons donated | H2 produced (μmol) | Electrons in H2 (μmol) | |||||

| Wild type | Thiosulfate | 0 | 56 (8) | 16 (10) | 32 (20) | 35 (4) | 56 (20) |

| Thiosulfate | 0.5 | 126 (22) | 45 (6) | 90 (12) | 79 (14) | 71 (4) | |

| Thiosulfate | 2.0 | 157 (2) | 61 (2) | 122 (4) | 98 (7) | 78 (2) | |

| Thiosulfate | 4.0 | 146 (10) | 56 (4) | 112 (8) | 92 (7) | 77 (14) | |

| NifA* | Thiosulfate | 0 | 144 (5) | 62 (3) | 124 (6) | 90 (3) | 86 (1) |

| Thiosulfate | 0.5 | 152 (2) | 56 (6) | 112 (12) | 96 (2) | 73 (6) | |

| Thiosulfate | 2.0 | 152 (3) | 31 (3) | 62 (6) | 97 (2) | 40 (4) | |

| Wild type | Acetate | 0 | 160 (0) | 34 (14) | 68 (28) | 100 (0)c | 43 (18) |

| Succinate | 0 | 280 (0) | 83 (15) | 166 (30) | 100 (0)c | 59 (11) | |

| None | 2.0 | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | ||||

| None | 0 | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | ||||

Data reported are the averages of two to four determinations ± standard deviations (in parentheses).

The maximum theoretical yield of H2 from thiosulfate or acetate is 4 mol H2/mol electron donor, and that from succinate it is 7 mol H2/mol electron donor. The percentage of the theoretical maximum yield is calculated from the amount of H2 gas produced from substrate consumed.

Substrate was oxidized below our detection limit of 10 nmol.

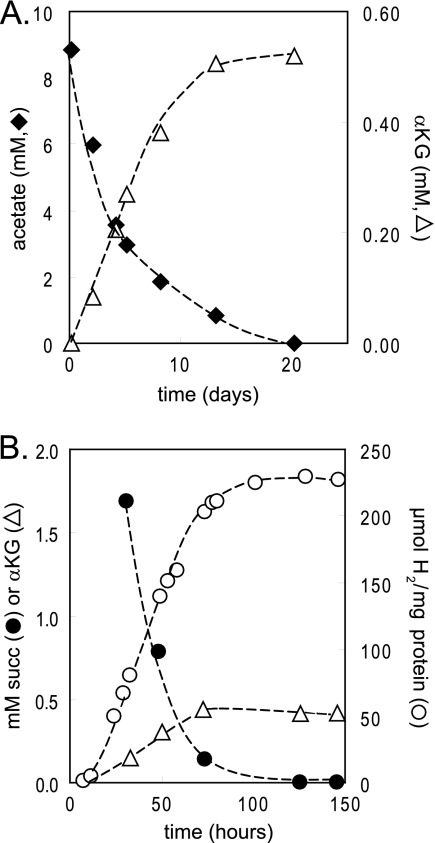

The efficiency of conversion of electrons from acetate or succinate to H2 by nongrowing wild-type cells was on the order of 45 to 60%, significantly lower than that measured for thiosulfate conversion (Table 1). Bicarbonate addition did not stimulate H2 production from these organic compounds (data not shown). Use of an organic electron donor may be relatively inefficient because cells have the option of incorporating reducing power and carbon from organic compounds into intracellular storage polymers such as poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (3, 5, 35). We also found that nongrowing cells excreted significant amounts of α-ketoglutarate along with H2 when they were incubated with acetate or succinate (Fig. 3). No excreted organic compounds were detected, as assessed by HPLC analysis, after incubation of nongrowing cells with thiosulfate either with or without bicarbonate.

FIG. 3.

α-Ketoglutarate (αKG) is produced by nongrowing cells incubated with acetate or succinate. R. palustris CGA009 excretes α-ketoglutarate (open triangles) over time when oxidizing acetate (filled diamonds) (A) or succinate (succ; filled circles) (B) under nongrowing conditions. R. palustris cultures were grown under nitrogen-fixing conditions, suspended in phosphate buffer under Ar gas, and provided with either 10 mM acetate or 4 mM succinate and incubated in light. H2 yields are shown for cells incubated with succinate (open circles).

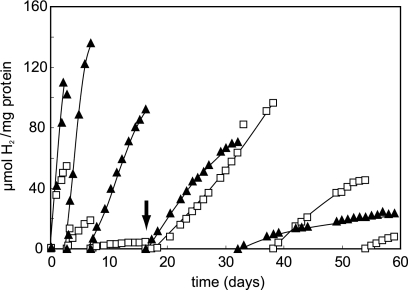

Long-term H2 production from nongrowing R. palustris cells using thiosulfate as an electron donor.

Suspensions of nongrowing R. palustris wild-type cells produced H2 continuously for several weeks when thiosulfate was supplied as an electron donor (Fig. 4). Cultures produced greater amounts of H2 at higher rates when 2 mM bicarbonate was included. Addition of bicarbonate 18 days following the first of incubation of cells with thiosulfate dramatically increased H2 production (Fig. 4). H2 production rates and yields decreased significantly after about 3 weeks with continual refeeding with thiosulfate.

FIG. 4.

Long-term H2 production from thiosulfate by nongrowing R. palustris incubated in light. R. palustris CGA009 was grown under nitrogen-fixing conditions in the presence of thiosulfate and resuspended in phosphate buffer with either 2 mM thiosulfate (open squares) or 2 mM thiosulfate and 2 mM bicarbonate (filled triangles). H2 production was measured, and cultures were refed electron donor over several weeks at the time points indicated by filled triangles or open squares at the baseline of the graph. Cultures were also flushed with Ar at these times. At 18 days, 2 mM bicarbonate was added to a culture previously provided only thiosulfate (arrow). Data are representative of experiments carried out in duplicate.

DISCUSSION

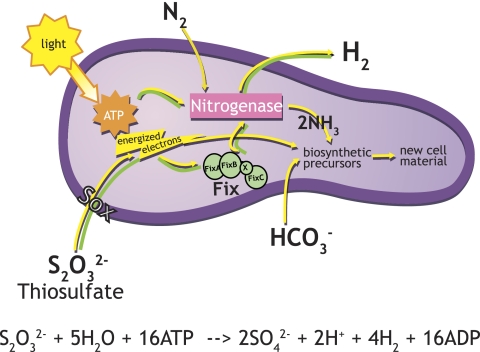

A model for photoautotrophic growth under nitrogen-fixing conditions, developed on the basis of known pathways and our results, is shown in Fig. 5, in which thiosulfate is oxidized using the periplasmic Sox enzyme complex (9, 22, 25). Electrons from thiosulfate are used for the synthesis of biosynthetic precursors and are also transferred to nitrogenase for synthesis of ammonia and H2 (Fig. 5, yellow arrows). In the absence of N2 under nongrowing conditions (Fig. 5, green arrows), electrons from thiosulfate are used in H2 production and not for synthesis of ammonia or biosynthetic precursors with the theoretical stoichiometry indicated in the equation in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

R. palustris H2 production by thiosulfate oxidation under growing and nongrowing conditions. Nongrowing R. palustris (green pathways) produce H2 using nitrogenase without the need to produce biosynthetic precursors necessary for growth (yellow pathways). Cells take up bicarbonate from the external environment and convert it to carbon dioxide, which is the substrate for Calvin cycle reactions. The theoretical stoichiometry for maximum H2 production from nongrowing cells using thiosulfate is given in the equation.

A possible explanation for the requirement for bicarbonate for H2 generation by wild-type cells in our short-term experiments is that the rate of thiosulfate oxidation is faster than the rate of H2 production, so that reduced cofactors build up in cells. R. palustris has carbonic anhydrases that convert bicarbonate to CO2, which enters the Calvin cycle, a pathway that has an electron-accepting function as well as a carbon dioxide fixation function (23). Thus, the Calvin cycle serves as a relief valve that enables cells to reoxidize reduced cofactors and to avoid slowing of metabolism (23). Consistent with this explanation is that H2 production by the nifA* mutant was not stimulated by bicarbonate addition. This mutant oxidized greater than 90% of the thiosulfate electron donor and produced high yields of H2 in the absence of bicarbonate (Table 1). The nifA* mutant has about 30% higher levels of expression of fixABCX and molybdenum nitrogenase genes than its wild-type parent (30). Higher concentrations of active nitrogenase may allow the NifA* strain to use H2 production to reoxidize greater amounts of reduced cofactors than the wild type. It is interesting that bicarbonate addition resulted in a decrease in H2 yields by the NifA* strain (Table 1). It is possible that carbon dioxide fixation draws electrons away from H2 production, resulting in decreased yields. We also cannot exclude the possibility that bicarbonate plays a regulatory role and acts as an effector to stimulate nitrogenase expression in the wild-type strain.

We found that when functioning as nongrowing biocatalysts, R. palustris cells converted electrons from acetate and succinate into H2 gas with less efficiency relative to when thiosulfate was used as an electron donor. One reason for this inefficiency is that cells excreted significant amounts of α-ketoglutarate. α-Ketoglutarate is central to nitrogen metabolism, as it is the acceptor molecule for the glutamine:α-ketoglutarate aminotransferase reaction that acts in conjunction with glutamine synthetase to assimilate ammonia (36). One interpretation is that R. palustris cells grown under nitrogen-fixing conditions have adjusted central metabolism to generate the relatively large amounts of α-ketoglutarate that would be needed for efficient assimilation of ammonia produced by nitrogenase. When cells are suspended in a nongrowing state and deprived of N2, α-ketoglutarate is not needed by cells and is excreted. It is also likely that cells incorporate some carbon and electrons from organic donors into cell biomass, even under nongrowing conditions, thus further decreasing efficiency of H2 production.

The fixABCX operon is required for nitrogen fixation by R. palustris (Fig. 2). R. rubrum fix mutants were previously shown to be defective in nitrogen fixation (7). It has been proposed that one electron from NADH is transferred to FixAB and then to ferredoxin (the direct electron donor to nitrogenase), while the other electron from NADH is transferred to FixCX and then to quinone, a component of the electron transfer chain. The deenergized electron carried by quinone is returned to the photosynthetic reaction center to be reenergized by light as R. palustris generates ATP by cyclic photophosphorylation. The bifurcation of electrons to FixAB and FixCX allows the exergonic transfer of an electron from NADH to quinone to drive the endergonic transfer of a second electron from NADH to ferredoxin (13). If transfer of electrons to nitrogenase is the rate-limiting step for H2 production, then manipulating the expression of the fix gene cluster in R. palustris may result in increases in H2 production.

R. palustris uses thiosulfate efficiently to produce H2 under nongrowing conditions, and H2 production from an inorganic electron donor does not generate carbon dioxide as a product. R. palustris cells suspended in phosphate buffer can produce H2 from thiosulfate for several weeks (Fig. 4), and cells could be concentrated for this purpose in small bioreactors (11). The rates of H2 production decrease over time; however, in the future, addition of vitamins or trace elements may improve long-term H2 production from resting cells. The possibility to use an inorganic electron donor like thiosulfate provides feedstock options for H2 production that can be used in combination with or beyond biomass-based electron donors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dale Pelletier for sharing the electroporation protocol prior to its publication and Amy Schaefer for assistance with figure preparation.

This work was funded by U.S. Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-07ER64482.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbosa, M. J., J. M. S. Rocha, J. Tramper, and R. H. Wijffels. 2001. Acetate as a carbon source for hydrogen production by photosynthetic bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 85:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmeyer, H. U., J. Bermeyer, and M. Bral. 1984. Methods of enzymatic analysis; metabolites 2: tri- and dicarboxylic acids, purines, pyrimidines and derivatives, coenzymes, inorganic compounds, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 3.Carlozzi, P., and A. Sacchi. 2001. Biomass production and studies on Rhodopseudomonas palustris grown in an outdoor, temperature controlled, underwater tubular photobioreactor. J. Biotechnol. 88:239-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, K. Y., and J. C. Morris. 1972. Kinetics of oxidation of aqueous sulfide by O2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 6:529-537. [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Philippis, R., A. Ena, M. Guastini, C. Sili, and M. Vincenzini. 1992. Factors affecting poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate accumulation in cyanobacteria and in purple nonsulfur bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 103:187-194. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edgren, T., and S. Nordlund. 2005. Electron transport to nitrogenase in Rhodospirillum rubrum: identification of a new fdxN gene encoding the primary electron donor to nitrogenase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245:345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edgren, T., and S. Nordlund. 2004. The fixABCX genes in Rhodospirillum rubrum encode a putative membrane complex participating in electron transfer to nitrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 186:2052-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fissler, J., C. Schirra, G. W. Kohring, and F. Giffhorn. 1994. Hydrogen production from aromatic acids by Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Appl. Microbiol. Biol. 41:395-399. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedrich, C. G., F. Bardischewsky, D. Rother, A. Quentmeier, and J. Fischer. 2005. Prokaryotic sulfur oxidation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:253-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghirardi, M. L., A. Dubini, J. Yu, and P. C. Maness. 2009. Photobiological hydrogen-producing systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38:52-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosse, J. L., B. J. Engel, F. E. Rey, C. S. Harwood, L. E. Scriven, and M. C. Flickinger. 2007. Hydrogen production by photoreactive nanoporous latex coatings of nongrowing Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009. Biotechnol. Prog. 23:124-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood, C. S. 2008. Nitrogenase-catalyzed hydrogen production by purple nonsulfur photosynthetic bacteria, p. 259-271. In J. D. Wall, C. S. Harwood, and A. Demain (ed.), Bioenergy. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 13.Herrmann, G., E. Jayamani, G. Mai, and W. Buckel. 2008. Energy conservation via electron-transferring flavoprotein in anaerobic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 190:784-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillmer, P., and H. Gest. 1977. H2 metabolism in photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas capsulata: H2 production by growing cultures. J. Bacteriol. 129:724-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorgensen, B. B. 1990. The sulfur cycle of freshwater sediments—role of thiosulfate. Limnol. Oceanogr. 35:1329-1342. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jorgensen, B. B., and F. Bak. 1991. Pathways and microbiology of thiosulfate transformations and sulfate reduction in a marine sediment (Kattegat, Denmark). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:847-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly, D. P., and A. P. Wood. 1998. Microbes of the sulfur cycle, p. 31-56. In R. A. R. S. Burlage, D. Stahl, G. Geesy, and G. Sayler (ed.), Techniques in microbial ecology. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- 18.Kim, M. K., and C. S. Harwood. 1991. Regulation of benzoate CoA ligase in Rhodopseudomonas palustris. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 83:199-203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovach, M. E., R. W. Phillips, P. H. Elzer, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1994. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. Biotechniques 16:800-802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larimer, F. W., P. Chain, L. Hauser, J. Lamerdin, S. Malfatti, L. Do, M. L. Land, D. A. Pelletier, J. T. Beatty, A. S. Lang, F. R. Tabita, J. L. Gibson, T. E. Hanson, C. Bobst, J. Torres, C. Peres, F. H. Harrison, J. Gibson, and C. S. Harwood. 2004. Complete genome sequence of the metabolically versatile photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luther, G. W., T. M. Church, J. R. Scudlark, and M. Cosman. 1986. Inorganic and organic sulfur cycling in salt marsh pore waters. Science 232:746-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masuda, S., S. Eda, S. Ikeda, H. Mitsui, and K. Minamisawa. 2010. Thiosulfate-dependent chemolithoautotrophic growth of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2402-2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKinlay, J. B., and C. S. Harwood. 2010. Carbon dioxide fixation as a central redox cofactor recycling mechanism in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:11669-11675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKinlay, J. B., and C. S. Harwood. 2010. Photobiological production of hydrogen gas as a biofuel. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21:244-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer, B., J. F. Imhoff, and J. Kuever. 2007. Molecular analysis of the distribution and phylogeny of the soxB gene among sulfur-oxidizing bacteria—evolution of the Sox sulfur oxidation enzyme system. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2957-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagl, G. J., M. Reicher, D. McManus, and B. Ferm. July 2000. Method for continuously producing thiosulfate ions. U.S. patent 6,083,472.

- 27.Oda, Y., F. W. Larimer, P. S. Chain, S. Malfatti, M. V. Shin, L. M. Vergez, L. Hauser, M. L. Land, S. Braatsch, J. T. Beatty, D. A. Pelletier, A. L. Schaefer, and C. S. Harwood. 2008. Multiple genome sequences reveal adaptations of a phototrophic bacterium to sediment microenvironments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:18543-18548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oda, Y., S. K. Samanta, F. E. Rey, L. Y. Wu, X. D. Liu, T. F. Yan, J. Z. Zhou, and C. S. Harwood. 2005. Functional genomic analysis of three nitrogenase isozymes in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J. Bacteriol. 187:7784-7794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelletier, D. A., G. B. Hurst, L. J. Foote, P. K. Lankford, C. K. McKeown, T. Y. Lu, D. D. Schmoyer, M. B. Shah, W. J. T. Hervey, W. H. McDonald, B. S. Hooker, W. R. Cannon, D. S. Daly, J. M. Gilmore, H. S. Wiley, D. L. Auberry, Y. Wang, F. W. Larimer, S. J. Kennel, M. J. Doktycz, J. L. Morrell-Falvey, E. T. Owens, and M. V. Buchanan. 2008. A general system for studying protein-protein interactions in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Proteome Res. 7:3319-3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rey, F. E., E. K. Heiniger, and C. S. Harwood. 2007. Redirection of metabolism for biological hydrogen production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1665-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rey, F. E., Y. Oda, and C. S. Harwood. 2006. Regulation of uptake hydrogenase and effects of hydrogen utilization on gene expression in Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J. Bacteriol. 188:6143-6152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolls, J. P., and E. S. Lindstrom. 1967. Effect of thiosulfate on photosynthetic growth of Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J. Bacteriol. 94:860-866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpson, F. B., and R. H. Burris. 1984. A nitrogen pressure of 50 atmospheres does not prevent evolution of hydrogen by nitrogenase. Science 224:1095-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith, G., and F. W. Sanders. July 1979. Process for production of sodium thiosulfate and sodium hydroxide. U.S. patent 4,162,187.

- 35.Vincenzini, M., A. Marchini, A. Ena, and R. DePhilippis. 1997. H2 and poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate, two alternative chemicals from purple non sulfur bacteria. Biotechnol. Lett. 19:759-762. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan, J., C. D. Doucette, W. U. Fowler, X. J. Feng, M. Piazza, H. A. Rabitz, N. S. Wingreen, and J. D. Rabinowitz. 2009. Metabolomics-driven quantitative analysis of ammonia assimilation in E. coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5:302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zopfi, J., T. G. Ferdelma, and H. Fossing. 2004. Distribution and fate of sulfur intermediates sulfite, tetrathionate, thiosulfate, and elemental sulfur in marine sediments, p. 97-116. In J. Amend, K. Edwards, and T. Lyons (ed.), Sulfur biogeochemistry past and present, vol. 379. Geological Society of America, Boulder, CO. [Google Scholar]