Abstract

In deep-sea hydrothermsal vent communities, viruses play very important roles. However vent thermophilic bacteriophages remain largely unexplored. In this investigation, a novel vent Geobacillus bacteriophage, D6E, was characterized. Based on comparative genomics and proteomics analyses, the results showed an extensive mosaicism of D6E genome with other mesophilc or thermophilic phages.

Bacteriophages are the most abundant life forms in the biosphere: they can be detected in almost every biological niche and represent a huge source of biodiversity (2, 3, 8, 11). Therefore, phages are thought to play very important roles in the ecological balance of microbial life and in microbial diversity (10, 25). This view has gained strong support from the work on viruses in extreme ecosystems, especially the deep-sea hydrothermal vents (5, 7, 14, 23). The isolation and characterization of viruses often lead to new insights into virus relationships and to a more detailed understanding of the biochemical environment of their host cells (15, 19, 21). Generally our understanding of the deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophages is far behind our knowledge of the terrestrial, mesophilic bacteriophages (31). The recent discoveries of many novel thermophilic bacteriophages, especially among members isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vents, are likely to lead to a more complete understanding of not only thermophiles, but also the biochemical adaptations required for the life in extreme environments, and to new insights into both host and virus evolution (14, 22, 24, 26-28, 30). Comparative viral genomics creates a wealth of information that has made it possible to construct gene and genome phylogenies as well as to observe complex relationships among virus genomes. However, bacteriophages that infect thermophilic eubacteria have remained largely unexplored (29). At present, only several genomes of thermophilic bacteriophages are available (14, 17, 18). Among them, only one phage from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent, i.e., GVE2, has been characterized at the molecular level (14). In this study, a deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage, D6E, was isolated. The comparative analysis of the genome sequences of D6E and GVE2 revealed extensive genetic mosaics.

During the cultivation of Geobacillus sp. strain E263 isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal field in the east Pacific (12°42′29″N, 104°02′01″W), many phage plaques were observed. The bacteriophage particles were purified from the host cultured at 65°C as described previously (14). The phage DNA was extracted and subjected to DNA sequencing as described previously (14). An initial set of open reading frames (ORFs) likely to encode proteins (coding sequences [CDSs]) was identified with the program Glimmer (6). All CDSs were compared to a nonredundant amino acid database. The BLAST algorithms were used for similarity searches in the databases available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (1). tRNAscan-SE was used to search for tRNAs (16). The rho-independent transcription terminators were detected with TransTerm (9). Multiple alignments were generated with the DNAMAN program (Lynnon Biosoft), using the ClustalW algorithm. The purified virions were subjected to mass spectrometry as described before (14). All peptide mass fingerprintings (PMFs) were analyzed with the protein search engine Mascot (Matrix Science, United Kingdom) against the genome sequence of the phage obtained in this study.

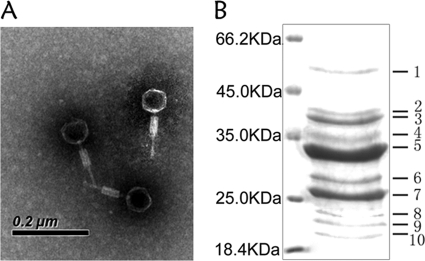

The results showed that D6E was a typical myovirus with an icosahedral capsid (60 nm in diameter), a contractile tail (16 nm in width and 60 nm in length), and a tail fiber (4 nm in width and 60 nm in length) (Fig. 1A). Based on these properties, the phage D6E belonged to the family of Myoviridae. The SDS-PAGE data indicated that the viral particle was composed of 10 proteins (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Characterizations of deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage D6E. (A) Electron micrograph of D6E virions. Scale bar, 200 nm. (B) SDS-PAGE of proteins from purified D6E virions, followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. The numbers indicate the excised bands for mass spectrometric analysis. The left lane contains the protein molecular mass marker (kDa).

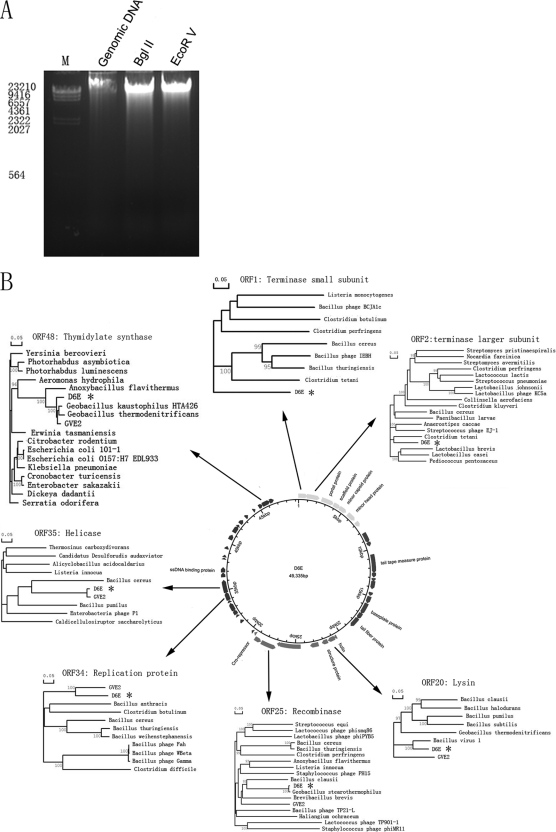

The sequencing results, more than 16-fold redundant, indicated that the phage contained a 49,335-bp double-stranded genomic DNA (dsDNA). Based on sequence analysis, there were only two restriction sites (one BglII and one EcoRV) in the D6E genome. After digestion of D6E genomic DNA with BglII or EcoRV, only one band was observed. The results suggested that the D6E genome might be circular (Fig. 2A). The PCR amplification data supported this finding.

FIG. 2.

Genome of D6E. (A) The viral genomic DNA of D6E. Native DNA was digested by BglI or HindII prior to electrophoresis. M, DNA marker. (B) Circular representation of the D6E genome map. The outer circle represents the D6E ORFs. The predicted protein coding sequences are indicated according to their corresponding homologues. Dendrograms are displayed for the predicted protein coding sequences with highly conserved homologues.

The genome of D6E contained 49 putative ORFs (Table 1 and Fig. 2B). As determined by tRNAscan analysis, the D6E genome did not carry any tRNA genes. Based on BLAST results, the D6E genome could be split into four clusters of genes with related functions. These clusters were supposed to support DNA packaging and capsid assembly, tail assembly, lysis, and lysogeny, as well as DNA replication and transcription (Fig. 2B and Table 1).

TABLE 1.

ORFs of deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage D6E

| ORF | Position in the genome (amino acid length) | Closest homologue in GenBank (accession no., E value, % identity) | Predicted function/feature | Identification by mass spectrometry |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | Sequence coverage (%) | ||||

| 1 | 1-900 (299) | Phage terminase small subunit, Bacillus thuringiensis strain Al Hakam (YP_891149.1, 5e−75, 52) | Phage terminase small subunit | ||

| 2 | 887-2170 (427) | Phage terminase, large subunit, pbsx family, Bacillus cereus W (ZP_03104491.1, 6e−172, 68) | Phage terminase, large subunit | ||

| 3 | 2466-3734 (422) | Phage portal protein, SPP1 family, Bacillus cereus AH1134 (ZP_03232437.1, 5e−85, 41) | Phage portal protein | 1 | 42 |

| 4 | 3816-4520 (235) | Hypothetical protein CTC01553, Clostridium tetani E88 (NP_782165.1, 5e−24, 35) | Phage scaffold protein | 7 | 50 |

| 5 | 4535-5304 (289) | Hypothetical protein Haur_0657, Herpetosiphon aurantiacus | Phage minor capsid protein | 5 | 82 |

| ATCC 23779 (YP_001543433.1, 2e−107, 65) | 6 | 64 | |||

| 8 | 64 | ||||

| 10 | 67 | ||||

| 6 | 5605-6510 (301) | Phage-related minor head protein, Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 14580 (YP_078649.1, 2e−33, 34) | Phage-related minor head protein | ||

| 7 | 6809-7315 (168) | Hypothetical protein Amet_0423, Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF (YP_001318310.1, 7e−22, 31) | |||

| 8 | 8196-9246 (349) | Hypothetical protein Amet_0426, Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF (YP_001318313.1, 3e−58, 37) | |||

| 9 | 9259-9663 (134) | Hypothetical protein Amet_0427, Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF (YP_001318314.1, 9e−21, 42) | Phage conserved protein | 3 | 64 |

| 10 | 10584-12494 (636) | Putative phage membrane protein, Clostridium botulinum C strain Eklund (ZP_02620637.1, 2e−26, 29) | Phage tail tape measure protein | ||

| 11 | 12494-12961 (156) | Hypothetical protein lin1715, Listeria innocua Clip11262 (NP_471051.1, 3e−11, 33) | |||

| 12 | 13063-13380 (105) | Hypothetical protein EF1475, Enterococcus faecalis V583 (NP_815196.1, 3e−19, 47) | |||

| 13 | 13370-14191 (274) | Hypothetical protein lin1713, Listeria innocua Clip11262 (NP_471049.1, 8e−65, 48) | |||

| 14 | 14567-14920 (117) | Hypothetical protein Amet_0435, Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF (YP_001318322.1, 2e−12, 37) | Phage-related protein | ||

| 15 | 15025-15735 (239) | HNH endonuclease family protein, Gramella forsetii KT0803 (YP_862450.1, 2e−29, 45) | |||

| 16 | 15804-16979 (391) | Hypothetical protein Amet_0436, Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF (YP_001318323.1, 1e−90, 45) | Baseplate protein | ||

| 17 | 16976-17617 (214) | Hypothetical protein Amet_0437, Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF (YP_001318324.1, 8e−46, 47) | |||

| 18 | 17630-18661 (343) | Hypothetical protein GK0545, Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 (YP_146398.1, 4e−23, 84) | Tail fiber protein | ||

| 19 | 20539-20802 (87) | Hypothetical protein Aflv_0679, Anoxybacillus flavithermus WK1 (YP_002315044.1, 4e−35, 89) | Holin | ||

| 20 | 20802-21485 (227) | Cell wall hydrolase/autolysin, Geobacillus sp. strain Y412MC61 (ZP_03558146.1, 1e−107, 85) | Lysin | ||

| 21 | 21584-22162 (192) | Hypothetical protein BH3064, Bacillus halodurans C-125 (NP_243930.1, 5e−47, 48) | Structure protein | 9 | 54 |

| 22 | 22587-23423 (278) | Hypothetical protein Nther_0358, Natranaerobius thermophilus JW/NM-WN-LF (YP_001916543.1, 5e−61, 47) | |||

| 23 | 24473-26731 (752) | Lipid A export ATP-binding/permease protein MsbA, Clostridium botulinum Bf (ZP_02619785.1, 1e−78, 30) | |||

| 24 | 26655-26909 (84) | Hypothetical protein BV1_gp42, Bacillus virus 1 (YP_001425622.1, 9e−16, 74) | |||

| 25 | 28508-27069 (479) | Putative recombinase, Geobacillus stearothermophilus (CAQ19390.1, 0.0, 98) | Putative recombinase | ||

| 26 | 29188-28568 (205) | Transcriptional regulator, XRE family, Paenibacillus sp. strain JDR-2 (ZP_02846182.1, 5e−58, 57) | Transcriptional regulator | ||

| 27 | 29346-29549 (67) | Transcriptional regulator, XRE family, Paenibacillus sp. strain JDR-2 (ZP_02846181.1, 3e−8, 46) | Cro repressor | ||

| 28 | 29721-29900 (59) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp030, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285836.1, 1e−22, 89) | |||

| 29 | 31242-31532 (96) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp064, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001522900.1, 2e−17, 48) | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||

| 30 | 32002-32199 (65) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp034, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285840.1, 6e−29, 92) | |||

| 31 | 32278-32757 (159) | Siphovirus Gp157-like protein, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285841.1, 3e−78, 78) | Siphovirus Gp157-like protein | ||

| 32 | 32754-33551 (265) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp036, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285842.1, 8e−115, 97) | |||

| 33 | 33678-33893 (71) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp066, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001522902.1, 7e−30, 90) | |||

| 34 | 33946-34759 (271) | Putative replication protein, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285845.1, 7e−89, 63) | Phage replication protein | ||

| 35 | 34770-36065 (431) | Putative DnaB-like helicase, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285846.1, 2e−170, 97) | Putative DnaB-like helicase | ||

| 36 | 36403-36837 (144) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp043, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285849.1, 1e−57, 65) | HNH endonuclease | ||

| 37 | 36902-37396 (164) | Putative ssDNAa binding protein, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285850.1, 1e−21, 80) | ssDNA binding protein | ||

| 38 | 38251-38388 (46) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp068, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001522904.1, 9e−12, 83) | |||

| 39 | 38487-38699 (70) | Hypothetical protein EFP_gp176, Enterococcus phage phiEF24C (YP_001504285.1, 5e−11, 46) | |||

| 40 | 39359-39637 (92) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp047, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285853.1, 5e−12, 37) | |||

| 41 | 40412-40921 (169) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp049, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285855.1, 3e−48, 64) | dUTPase | ||

| 42 | 41255-41974 (239) | Conserved hypothetical protein, Bacillus cereus 03BB108 (ZP_03115270.1, 1e−54, 49) | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||

| 43 | 41992-42171 (59) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp050, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285856.1, 1e−17, 90) | |||

| 44 | 42376-42807 (143) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp051, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285857.1, 9e−12, 35) | Possible sensor protein | ||

| 45 | 43233-43535 (99) | Conserved hypothetical protein, Geobacillus sp. strain Y412MC61 (ZP_03558114.1, 3e−41, 84) | Group-specific protein | ||

| 46 | 44296-44529 (77) | Hypothetical protein GBVE2_gp054, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285860.1, 4e−31, 89) | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||

| 47 | 44999-45409 (136) | Hypothetical protein BC03BB108_E0069, Bacillus cereus 03BB108 (ZP_03115598.1, 1e−31, 51) | |||

| 48 | 45437-46231 (264) | Putative thymidylate synthase, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001285862.1, 4e−149, 95) | Phage thymidylate synthase | ||

| 49 | 46247-46678 (143) | RinA transcriptional activator-like protein, Geobacillus virus E2 (YP_001522905, 2e−58, 75) | RinA transcriptional activator-like protein | ||

ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

The mass spectrometric identification of 10 proteins of D6E virions presented the unambiguous identification of five unique proteins, covering 42 to 82% of amino acid sequences (Table 1). The results showed that one of the major protein bands was the product of ORF 5 (major capsid protein) (Fig. 1B and Table 1). This protein was also found in the bands 6, 8, and 10. The proteomics approach proved that some ORFs were indeed protein-coding sequences, although the proteins had no functionally assigned homologs in the database: e.g., the protein encoded by ORF 21 (band 9).

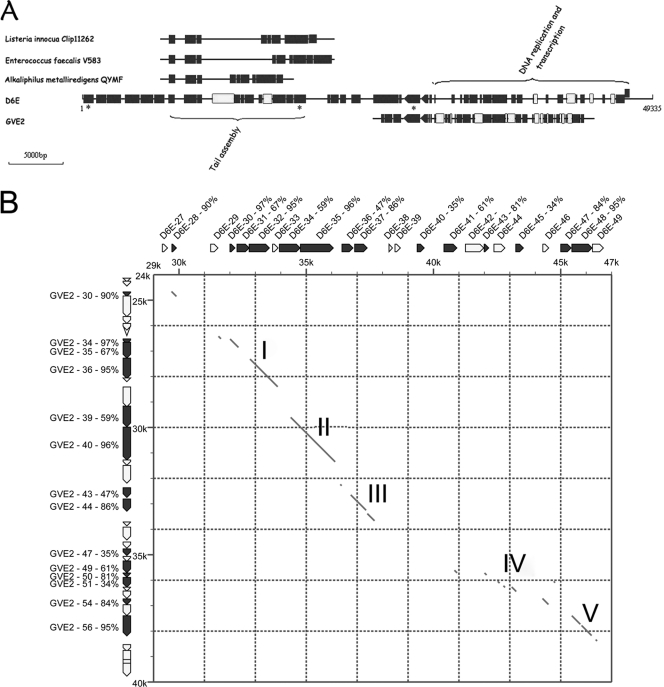

Although the conservation of the gene order in the D6E genome was remarkable to other bacteriophages, the D6E genome sequence shared low similarity to the known phages. Based on sequence analysis, the D6E genome displayed extensive mosaicism of genes with other species (Fig. 3). The D6E genes belonging to the tail assembly gene cluster showed high similarity to those of three mesophilic bacteriophages (Listeria innocua Clip 11262, Enterococcus faecalis V583, and Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF), and the D6E genes from the DNA replication and transcription gene cluster were very highly similar to those of another deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage, GVE2 (Fig. 3A), suggesting the existence of gene or gene fragment transfers among bacteria and/or bacteriophages belonging to different species or genera through recombinant events. The analysis showed that D6E, a member of the Myoviridae, shared low sequence similarity with thermophilic bacteriophage GVE2 (Siphoviridae). However, both phages showed high identities in the DNA replication and transcription gene cluster (Fig. 3A and B). Considering that D6E and GVE2 were bacteriophages infecting thermophiles, the results suggested that the DNA replication and transcription gene cluster played very important roles in response to high temperature.

FIG. 3.

Mosaicism in bacteriophage D6E. Multiple alignments were generated with DNAMAN program (Lynnon Biosoft) using the ClustalW algorithm. (A) Comparative genomics among D6E, three mesophilic bacteriophages (Listeria innocua Clip 11262, Enterococcus faecalis V583, and Alkaliphilus metalliredigens QYMF), and deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage GVE2. The full-length D6E genome is displayed, while the partial genomes of three mesophilic phages and GVE2 with similarities to D6E are shown. Black boxes represent genes with high similarities, and white boxes show genes with low similarities. (B) Comparison of DNA replication and transcription gene cluster between D6E and GVE2. The regions of D6E and GVE2 were compared by a dot-matrix-dot method. Gene positions are indicated in thousands. The diagonal lines show regions where the nucleotide sequences were matched. The nucleotide and protein sequence similarity extended five segments over the DNA transcription and replication region I∼V. The percentages show amino acid sequence similarities between ORFs from bacteriophages D6E and GVE2.

Up to date, mosaic genomes of bacteriophages have been from mesophilic phages (4, 12, 13, 20). In this investigation, our study provided the first report on the mosaicism of viral genome in a deep-sea vent community. Based on D6E genome structure, it could be suggested that at least three recombination events (the overall gene organization, recombination between gene boundaries, and mutation in gene sequences) that appeared to have arisen by illegitimate recombination occurred sufficiently. The mosaic nature of D6E highlighted that mobile DNA elements like bacteriophages contributed substantial amounts of foreign DNAs to deep-sea vent community genomes in evolution. Therefore, our findings open up a realm of opportunities for studying horizontal gene transfer and for investigating the evolution of bacterial communities in deep-sea vents.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequences reported in this article may be found in the GenBank database under accession no. GU568037.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (40876070), the China Ocean Mineral Resources R&D Association (DYXM-115-02-2-15), and The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angly, F. E., B. Felts, M. Breitbart, P. Salamon, R. A. Edwards, C. Carlson, A. M. Chan, M. Haynes, S. Kelley, H. Liu, J. M. Mahaffy, J. E. Mueller, J. Nulton, R. Olson, R. Parsons, S. Rayhawk, C. A. Suttle, and F. Rohwer. 2006. The marine viromes of four oceanic regions. PLoS Biol. 4:e368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casas, V., and F. Rohwer. 2007. Phage metagenomics. Methods Enzymol. 421:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark, A. J., W. Inwood, T. Cloutier, and T. S. Dhillon. 2001. Nucleotide sequence of coliphage HK620 and the evolution of lambdoid phages. J. Mol. Biol. 311:657-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corliss, J. B., J. Dymond, L. I. Gordon, J. M. Edmond, R. P. von Herzen, R. D. Ballard, K. Green, D. Williams, A. Bainbridge, K. Crane, and T. H. van Andel. 1979. Submarine thermal springs on the Galapagos Rift. Science 203:1073-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delcher, A. L., K. A. Bratke, E. C. Powers, and S. L. Salzberg. 2007. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 23:673-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desiere, F., S. Lucchini, and H. Brussow. 1998. Evolution of Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophage genomes by modular exchanges followed by point mutations and small deletions and insertions. Virology 241:345-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards, R. A., and F. Rohwer. 2005. Viral metagenomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:504-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ermolaeva, M. D., H. G. Khalak, O. White, H. O. Smith, and S. L. Salzberg. 2000. Prediction of transcription terminators in bacterial genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 301:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foley, S., S. Lucchini, M. C. Zwahlen, and H. Brussow. 1998. A short noncoding viral DNA element showing characteristics of a replication origin confers bacteriophage resistance to Streptococcus thermophilus. Virology 250:377-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendrix, R. W. 2002. Bacteriophages: evolution of the majority. Theor. Popul. Biol. 61:471-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendrix, R. W., M. C. Smith, R. N. Burns, M. E. Ford, and G. F. Hatfull. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juhala, R. J., M. E. Ford, R. L. Duda, A. Youlton, G. F. Hatfull, and R. W. Hendrix. 2000. Genomic sequences of bacteriophages HK97 and HK022: pervasive genetic mosaicism in the lambdoid bacteriophages. J. Mol. Biol. 299:27-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, B., and X. Zhang. 2008. Deep-sea thermophilic Geobacillus bacteriophage GVE2 transcriptional profile and proteomic characterization of virions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 80:697-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Garcia, P., S. Duperron, P. Philippot, J. Foriel, J. Susini, and D. Moreira. 2003. Bacterial diversity in hydrothermal sediment and epsilonproteobacterial dominance in experimental microcolonizers at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Environ. Microbiol. 5:961-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe, T. M., and S. R. Eddy. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minakhin, L., M. Goel, Z. Berdygulova, E. Ramanculov, L. Florens, G. Glazko, V. N. Karamychev, A. I. Slesarev, S. A. Kozyavkin, I. Khromov, H. W. Ackermann, M. Washburn, A. Mushegian, and K. Severinov. 2008. Genome comparison and proteomic characterization of Thermus thermophilus bacteriophages P23-45 and P74-26: siphoviruses with triplex-forming sequences and the longest known tails. J. Mol. Biol. 378:468-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naryshkina, T., J. Liu, L. Florens, S. K. Swanson, A. R. Pavlov, N. V. Pavlova, R. Inman, L. Minakhin, S. A. Kozyavkin, M. Washburn, A. Mushegian, and K. Severinov. 2006. Thermus thermophilus bacteriophage phiYS40 genome and proteomic characterization of virions. J. Mol. Biol. 364:667-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nercessian, O., Y. Fouquet, C. Pierre, D. Prieur, and C. Jeanthon. 2005. Diversity of Bacteria and Archaea associated with a carbonate-rich metalliferous sediment sample from the Rainbow vent field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Environ. Microbiol. 7:698-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedulla, M. L., M. E. Ford, J. M. Houtz, T. Karthikeyan, C. Wadsworth, J. A. Lewis, D. Jacobs-Sera, J. Falbo, J. Gross, N. R. Pannunzio, W. Brucker, V. Kumar, J. Kandasamy, L. Keenan, S. Bardarov, J. Kriakov, J. G. Lawrence, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., R. W. Hendrix, and G. F. Hatfull. 2003. Origins of highly mosaic mycobacteriophage genomes. Cell 113:171-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postec, A., L. Urios, F. Lesongeur, B. Ollivier, J. Querellou, and A. Godfroy. 2005. Continuous enrichment culture and molecular monitoring to investigate the microbial diversity of thermophiles inhabiting deep-sea hydrothermal ecosystems. Curr. Microbiol. 50:138-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice, G., K. Stedman, J. Snyder, B. Wiedenheft, D. Willits, S. Brumfield, T. McDermott, and M. J. Young. 2001. Viruses from extreme thermal environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:13341-13345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohwer, F., and R. V. Thurber. 2009. Viruses manipulate the marine environment. Nature 459:207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suttle, C. A. 2007. Marine viruses—major players in the global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:801-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suttle, C. A. 2005. Viruses in the sea. Nature 437:356-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takami, H., Y. Takaki, G. J. Chee, S. Nishi, S. Shimamura, H. Suzuki, S. Matsui, and I. Uchiyama. 2004. Thermoadaptation trait revealed by the genome sequence of thermophilic Geobacillus kaustophilus. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:6292-6303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, Y., and X. Zhang. 2008. Identification and characterization of a novel thymidylate synthase from deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage Geobacillus virus E2. Virus Genes 37:218-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei, D., and X. Zhang. 2008. Identification and characterization of a single-stranded DNA-binding protein from thermophilic bacteriophage GVE2. Virus Genes 36:273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei, D., and X. Zhang. Proteomic analysis of interactions between a deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage and its host at high temperature. J. Virol. 84:2365-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ye, T., and X. Zhang. 2008. Characterization of a lysin from deep-sea thermophilic bacteriophage GVE2. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 78:635-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu, M. X., M. R. Slater, and H. W. Ackermann. 2006. Isolation and characterization of Thermus bacteriophages. Arch. Virol. 151:663-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]