Abstract

Exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis can result in lifelong but asymptomatic infection in most individuals. Although CD8+ T cells are elicited at high frequencies over the course of infection in both humans and mice, how phagosomal M. tuberculosis Ags are processed and presented by MHC class I molecules is poorly understood. Broadly, both cytosolic and noncytosolic pathways have been described. We have previously characterized the presentation of three HLA-I epitopes from M. tuberculosis and shown that these Ags are processed in the cytosol, whereas others have demonstrated noncytosolic presentation of the 19-kDa lipoprotein as well as apoptotic bodies from M. tuberculosis-infected cells. In this paper, we now characterize the processing pathway in an additional six M. tuberculosis epitopes from four proteins in human dendritic cells. Addition of the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi trafficking inhibitor, brefeldin A, resulted in complete abrogation of Ag processing consistent with cytosolic presentation. However, although addition of the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin blocked the presentation of two epitopes, presentation of four epitopes was enhanced. To further examine the requirement for proteasomal processing of an epoxomicin-enhanced epitope, an in vitro proteasome digestion assay was established. We find that the proteasome does indeed generate the epitope and that epitope generation is enhanced in the presence of epoxomicin. To further confirm that both the epoxomicin-inhibited and epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes are processed cytosolically, we demonstrate that TAP transport and new protein synthesis are required for presentation. Taken together, these data demonstrate that immunodominant M. tuberculosis CD8+ Ags are processed and presented using a cytosolic pathway.

Tuberculosis disease remains a global health concern because of the large global burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected individuals, the emergence of multidrugand extensively drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains, and the disastrous consequences of coinfection with M. tuberculosis and HIV. Control of M. tuberculosis infection is facilitated by the development of an adaptive CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immune response and the coordinated development of antimycobacterial effector mechanisms, such as production of proinflammatory cytokines (1, 2), antibacterial proteins (3, 4), and proapoptotic capacity (5–8). Because of the importance of cell-mediated immunity for control of M. tuberculosis infection, further understanding of the factors that promote both efficient T cell priming and recognition of infected cells are important for development of an effective M. tuberculosis vaccine.

M. tuberculosis is able to modulate the phagosomal environment after internalization, characterized by incomplete phagosomal acidification, incomplete maturation of phagosomes to a rab7+ late endosome, lack of phagolysosomal biogenesis, and continued access to extracellular nutrients, such as iron, through the ongoing fusion of early endosomes (9). Although M. tuberculosis is able to evade innate immune mechanisms within phagocytic cells, this does not mean that M. tuberculosis infection goes unnoticed. The phagosome is a component of the HLA-II processing and presentation pathway, which serves to alert CD4+ T cells to the presence of exogenous Ags. Indeed, CD4+ T cells are elicited at high frequencies after M. tuberculosis infection and are vital for host protection. Alternately, because the phagosome is walled off from the cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived HLA-I processing and loading machinery, how M. tuberculosis Ags are processed and presented on HLA-I molecules is much less understood. Studies using bead phagosomes have shown that multiple pathways are functional. Ags can either escape the phagosome to the cytosol where they are degraded by the proteasome (cytosolic pathway) or remain within the endocytic pathway where they are degraded (vacuolar or noncytosolic pathway). In vivo data have suggested that the major pathway of cross-presentation and cross-priming is TAP and immunoproteasome dependent (10–16), providing evidence for the important role of the cytosolic pathway in the priming of the CD8+ T cell response. Nonetheless, cross-priming of cell-associated and viral Ags has been demonstrated to occur in the absence of TAP and, in some cases, relies on processing by cathepsin S (14).

The pathways by which M. tuberculosis Ags are presented on HLA-I are only beginning to be understood. Detailed analysis of presentation of three epitopes from two M. tuberculosis proteins has shown that M. tuberculosis Ags can be retrotranslocated out of the phagosome, giving them access to the cytosol (17). Once cytosolic, M. tuberculosis proteins require proteasomal degradation and TAP transport into either the ER or back into the phagosome, showing the use of the cytosolic processing and presentation pathway (17, 18). Conversely, there is support for endocytic processing of M. tuberculosis-derived Ags and apoptotic bodies. Presentation of the 19-kDa lipoprotein (lpqh) did not require TAP transport but did require trafficking outside of the mycobacterial phagosome (19). One striking feature of mycobacterially infected cells is the large amounts of vesicular trafficking of bacterial-derived proteins and lipids seen within the cell (20–22). This finding suggests that M. tuberculosis proteins may have unique access to the endocytic pathway, as well as access to bystander cells. Along those lines, Schaible et al. (8) showed that apoptotic bodies from mycobacterially-infected cells can be taken up by uninfected bystander cells and processed in an acidification-dependent but proteasome-independent manner. In all, these findings present a diverse picture of Ag processing and presentation pathways in M. tuberculosis-infected cells.

In this report, we seek to provide a more broad understanding of which pathway(s) are required for HLA-I presentation of six recently defined epitopes from secreted M. tuberculosis proteins. We screened Ag presentation in M. tuberculosis-infected cells using inhibitors that definitively distinguish cytosolic from noncytosolic pathways and find that presentation of all six of these epitopes use the cytosolic pathway.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Inhibitors of Ag processing were obtained from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA; epoxomicin, bafilomycin, leupeptin, pepstatin A, and AAF-CMK), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO; chloroquine and cycloheximide), or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA; brefeldin A [BFA]). Soluble CFP10 protein was provided by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals (Hamilton, MT). Peptides were synthesized by Genemed Synthesis (South San Francisco, CA).

Bacteria, virus, and cells

H37Rv-eGFP has been described previously (17). Before infection, bacteria were sonicated for 20 s, passaged 15 times through a tuberculin syringe, and sonicated again to obtain a single-cell suspension. Multiplicity of infection (MOI) varied depending on the experiment. Adenovirus-ICP47 (23) and other adenoviral vectors were provided by Dr. D. Johnson (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR).

PMBCs were obtained from human donors via leukapheresis according to Institutional Review Board-approved protocols and processed as described previously (24). Dendritic cells (DCs) were generated by culturing adherent PBMCs for 5 d in the presence of GM-CSF (10 ng/ml; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% pooled human serum (HS), l-glutamine (4 mM; Invitrogen), and gentamicin (50 μg/ml; Invitrogen).

T cell expansion

The T cell clones used in this report are detailed in Table I. T cell clones were expanded as previously described (18), except that some of the expansions were done in Stemline T cell expansion media (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 1% FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT) and 4 mM l-glutamine.

Table I.

Summary of clones used

| Clone Name | Aga | Amino Acid Sequence | Restricting Allele | Ex Vivo Frequencyb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D160 1–23 | ND | ND | HLA-E | ND | 24, 27 |

| D480 F6 | CFP103–11 | EMKTDAATL | HLA-B0801 | 1/646 | 26 |

| D466 H4 | CFP102–9 | AEMKTDAA | HLA-B4501 | 1/102 | 26 |

| D466 D6 | CFP102–12 | AEMKTDAATLA | HLA-B4501 | 1/125 | 26 |

| D481 C10 | CFP1075–83 | NIRQAGVQY | HLA-B1502 | 1/146 | 26 |

| D504 B10 | EsxJ24–34 | QTVEDEARRMW | HLA-B5701 | 1/55 | Unpublishedc |

| D454 H1-2 | DPV33–43 | AVINTTCNYGQ | HLA-B1501 | 1/10,417 | 26 |

| D443 H9 | Ag85B14–153 | ELPQWLSANR | HLA-B4102 | <1/25,000 | 26 |

| D454 E12 | CFP10 | ND | HLA-II | ND | 17 |

Numbers denote amino acid position within the protein.

Frequency of CD8+ T cells present in PBMCs specific for the indicated epitope.

D.M. Lewinsohn, G.M. Swarbrick, M.E. Cansler, M.D. Null, V. Rajaraman, B. Park, M. Frieder, D. Sherman, S. McWeeney, and D.A. Lewinsohn, manuscript in preparation.

ELISPOT assay

IFN-γ ELISPOT was performed as described previously (24).

Inhibition of Ag presentation

Day 5 DCs were plated in a 24-well ultralow adherence plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) at 5 × 105/well in RPMI 1640 medium/10% HS supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4. DCs were pretreated with inhibitors (1–10 μM epoxomicin, 0.1 μg/ml BFA, 0.2 μM bafilomycin, or 10 μg/ml cycloheximide) for 1 h prior to infection with H37Rv-eGFP (MOI = 20) or addition of Ag.

DCs were harvested after 15–16 h of infection, pelleted, and fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with an equal volume of 0.4 M lysine or RPMI 1640 medium/10% HS, and DCs were washed extensively with RPMI 1640 medium/10% HS. Fixed DCs were then added to an IFN-γ ELISPOT plate at varying quantities so that Ag was the limiting factor (25,000 M. tuberculosis-infected DCs/well for CD8+ clones, 1,000 M. tuberculosis-infected DCs/well for CD4+ clones, and 2,000 Ag-pulsed DCs/well for both CD4+ and CD8+ clones). This MOI and number of DCs per well were used to obtain strong T cell responses, which are still able to be inhibited with blockers of Ag presentation, as reported previously (18, 25). T cell clones were added in excess at 10,000/well, and plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h before development.

ICP47-mediated TAP inhibition

DCs were tranduced with adenovirus using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as described previously (18). After 6–26 h of incubation with adenovirus, media were removed and replaced with RPMI 1640 medium/10% HS containing H37Rv-eGFP (MOI = 15–20 for CD8+ T cell clones, 0.2–1 for CD4+ clones) or Ag (0.25–1 μg/ml cognate peptides, 5–50 ng/ml soluble CFP10) and incubated overnight at 37°C. After 15–16 h, media were removed, and T clones were added (1.5 × 105/well) in the presence of BFA (10 μg/ml). After a 6-h stimulation, T cell clones were harvested, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and stained with Abs to CD3 (UCHT1; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and IFN-γ (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) in the presence of 0.2% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur or LSR II (BD Biosciences).

In vitro proteasome digestion

A synthetic peptide encompassing aa 2–21 of CFP10 (AEMKTDAATLAQEAGNFERI) was synthesized, purified to >90% purity (Genemed Synthesis), and resuspended in PBS. Purified 20S immunoproteasomes (5 μg; BIOMOL, Plymouth Meeting, PA) were incubated with 50 μg peptide in a total of volume of 0.5 ml proteasome digestion buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl and 0.5 mM EDTA [pH 7.6]) for 20 h at 37°C in the presence or absence of epoxomicin (1 μM) or chymotrypsin (10 μg/ml; EMD Biosciences). The resulting digests were centrifuged through a Microcon tube with a 10-kDa cutoff and the flow-through frozen at 280°C.

Proteasome digests (20 pmol) were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an Agilent 1100 series capillary LC system (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) and an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA). Electrospray ionization was performed with an ion max source fitted with a 34-gauge metal needle. Samples were applied at 20 ml/min to a trap cartridge (Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA) and then switched onto a 0.5 × 250-mm Zorbax SB-C18 column (Agilent) using a mobile phase containing 0.1% formic acid, 7–30% acetonitrile gradient over 30 min, and 10 ml/min flow rate. Survey (MS) scans to determine the m/z values of the eluting peptides were alternated with three data-dependent MS/MS spectra, where individual peptide ions were isolated and fragmented to determine their amino acid sequences. The collection of these MS/MS spectra used the dynamic exclusion feature of the instrument's control software so that both major and minor ions in the survey MS spectra triggered data-dependent MS/MS scans. Peptide sequences were determined by comparing the observed MS/MS spectra to theoretical MS/MS spectra of peptides generated from a Uniprot protein database containing 223,100 entries and the program Sequest (version 27, revision 12; ThermoFinnigan) with no specification of potential cleavage sites and using a differential search for oxidized methionines. Summaries of identified peptides were then tabulated using BioWorks software (version 3.3; ThermoFinnigan) and were data filtered so that peptide probabilities were 1.0 × 10–24 or better. The extent of peptide cleavage in each incubated sample was measured by the decrease in the area of the base peak for the intact peptide in each chromatogram using Xcalibur software (ThermoFinnigan) and the appearance of new base peaks in the chromatograms for the various degraded forms of the peptide identified both by mass and by Sequest analysis.

T cell clone analysis of digests were performed in Stemline T cell expansion media (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 4 mM l-glutamine in the absence of serum to prevent further proteolysis by serum proteins. Proteasome digests or synthetic peptides were diluted in Stemline serum-free media and incubated with T cell clones (20,000/well) in the presence or absence of HLA-matched lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) (20,000/well) for 18–20 h in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. When present, LCLs were loaded with indicated peptides or proteasomal digests for 1 h prior to addition of T cells.

Results

Presentation of M. tuberculosis Ags requires ER-Golgi transport but not acidification

Using CD8+ T cells cloned from individuals with latent or active tuberculosis, our laboratory has identified M. tuberculosis-derived HLA-I epitopes. This Ag discovery method includes cloning CD8+ T cells on M. tuberculosis-infected DCs, determination of the Ag recognized using overlapping peptide pools, and subsequent determination of the minimal epitope and restricting allele (26–28). CD8+ T cell clones used in this paper and the minimal epitopes and restricting allele are summarized in Table I. Of note, we have found preferential use of HLA-B alleles for the presentation of M. tuberculosis Ags, and generally, responses to these epitopes make up a substantial proportion of the M. tuberculosis-specific CD8+ response in the individual from which they were defined (Table I) (26).

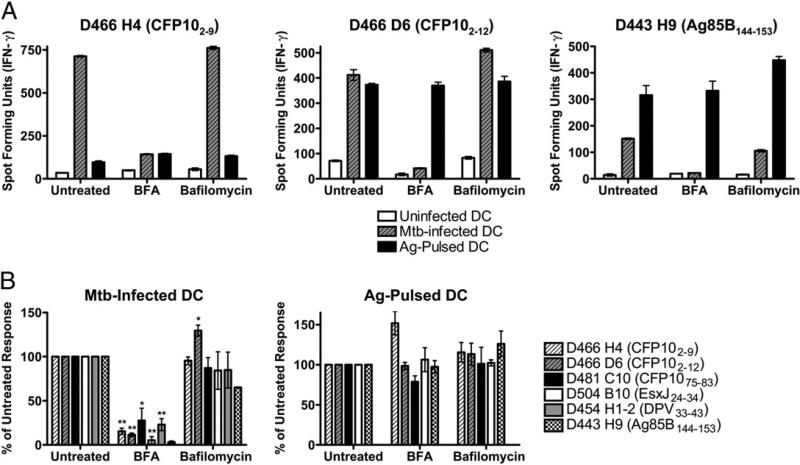

CD8+ T cell clones were used to monitor the processing and presentation requirements of the specific epitopes recognized by each clone, using inhibitors that distinguish cytosolic and noncytosolic processing pathways. Presentation of M. tuberculosis Ags in human DCs was first screened in the presence of ER-Golgi transport (BFA), acidification (bafilomycin), as well as proteasome (epoxomicin) blockade. In brief, DCs were treated with inhibitors for 1 h prior to infection with an H37Rv strain that expresses eGFP. After 15–16 h of infection in the presence of inhibitors, DCs were harvested, fixed, washed extensively, and used as stimulators in an overnight IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Using eGFP fluorescence as a marker for intracellular infection, we were unable to detect significant differences in the percentage of cells infected or the degree of infection after treatment with these inhibitors (data not shown), demonstrating that inhibitor treatment did not affect uptake of bacteria. As shown in Fig. 1, treatment with the ER-Golgi trafficking inhibitor BFA resulted in a marked reduction in presentation of all of the epitopes examined. These data are consistent with the cytosolic presentation pathway (29). Conversely, vacuolar processing of phagosomal Ags for class I presentation generally requires acidification (8, 30). As shown in Fig. 1, treatment of DCs with the vacuolar ATPase inhibitor, bafilomycin, did not significantly inhibit presentation of any of the epitopes tested. To ensure that bafilomycin was effective at the concentration used, DCs were pretreated with bafilomycin or DMSO as a control and then incubated with beads labeled with pH-dependent (fluorescein) and pH-independent (Alexa Fluor 647) dyes. When cells that had internalized a single bead were compared, bafilomycin-treated cells showed a 2-fold increase in fluorescein fluorescence, with no increase seen in Alexa Fluor 647 fluorescence (data not shown), indicating that bafilomycin did in fact raise the phagosomal pH. Presentation of synthetic peptides was not inhibited in the presence of BFA or bafilomycin, arguing against nonspecific effects of drug treatment. Taken together, these data demonstrate that presentation of all six epitopes require ER-Golgi transport, with little to no requirement for phagosomal acidification.

FIGURE 1.

Presentation of M. tuberculosis Ags requires ER-Golgi transport but not acidification. DCs were pretreated with BFA (0.1 μg/ml) or bafilomycin (0.2 μM) for 1 h prior to infection with H37Rv-eGFP (MOI = 20) or addition of peptide Ag (1 μg/ml). After 15–16 h in the presence of inhibitor, DCs were fixed, washed, and used as stimulators in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay (25,000 M. tuberculosis-infected DCs/well, 2,000 peptide-pulsed DCs/well) where CD8+ T cell clones are effectors (10,000 cells/well). A, Representative experiment for three clones. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells. B, Data have been normalized to the untreated control, and each bar reflects the mean ± SEM of at least three experiments per clone (two for D443 H9). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 using two-tailed Student t test compared with untreated controls. Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

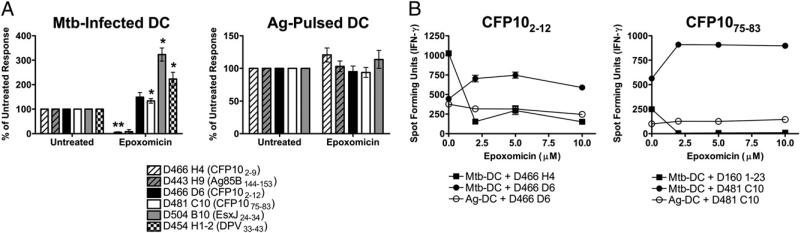

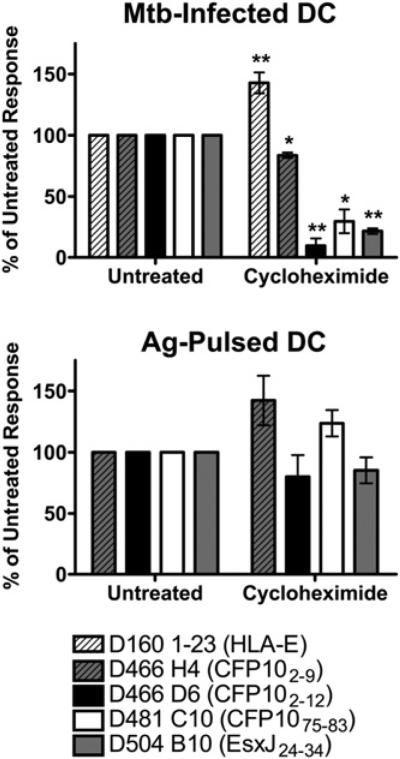

Epoxomicin can either inhibit or enhance Ag presentation

Proteasomal processing of Ags is a central feature of the cytosolic Ag-processing pathway. We have previously reported that three M. tuberculosis epitopes require proteasomal degradation [CFP102–11 (18), CFP103–11 (17), and an undefined Ag presented by HLA-E (17, 27)]. Unexpectedly, treatment of DCs with the specific proteasomal blocker epoxomicin showed that this inhibitor could either inhibit or enhance presentation of the examined epitopes (Fig. 2A, 2B). Although presentation of CFP102–9 and Ag85B144–153 epitopes was ablated in the presence of epoxomicin, presentation of CFP102–12, CFP1075–83, EsxJ24–34, and DPV33–43 epitopes was markedly enhanced. Schwarz et al. (31) reported that low-dose epoxomicin and lactacystin can paradoxically enhance Ag presentation of some epitopes, although higher doses inhibit it. However, presentation of neither CFP102–12 nor CFP1075–83 epitope was inhibited by epoxomicin treatment at concentrations up to 10 μM (Fig. 2B). This is the highest dose of epoxomicin that was nontoxic to DCs and is >20-fold higher than the dose generally required for maximal inhibition of Ag presentation in DCs (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that the proteasome can either generate or destroy the correct M. tuberculosis-derived epitope.

FIGURE 2.

Presentation of M. tuberculosis epitopes is either inhibited or enhanced by epoxomicin. DCs were treated with epoxomicin (1–10μM), infected with H37Rv-eGFP or pulsed with peptide, and used as APCs in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as described in Fig. 1. A, Data have been normalized to the untreated control, and each bar represents the mean ± SEM of at least three experiments (two for D443 H9). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 using two-tailed Student t test compared with untreated controls. B, DCs were treated with increasing concentrations of epoxomicin, infected with M. tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis-DCs) or pulsed with cognate peptides (Ag-DCs), and used as stimulators as described. One representative experiment of three is shown. Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Generation of epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes does not require tripeptidyl peptidase II or endocytic processing

Given these data, we reasoned that the epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes were either generated using a lysosomal or cytosolic protease or were generated by the proteasome in a manner refractory to epoxomicin blockade. To date, tripeptidyl peptidase II (TPPII) is the only other cytosolic protease described that is able to generate the correct C terminus of epitopes for MHC class I (MHC-I) presentation. TPPII is necessary for the generation of an HIV nef (32) and an influenza virus nucleoprotein epitope (33). To establish a role for TPPII in the generation of the epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes, the TPPII inhibitor AAF-CMK was tested for its ability to block presentation of the EsxJ24–34 or CFP1075–83 epitope. However, no effect of this inhibitor was observed at the highest possible nontoxic dose (data not shown). Alternately, the lysosomal proteases cathepsins D and S have been shown to participate in presentation of phagocytosed Ags (14, 34). Treatment with the cathepsin inhibitors leupeptin or pepstatin A did not block presentation of the EsxJ24–34 or CFP1075–83 epitope (data not shown). Furthermore, presentation of neither of these epitopes was inhibited in the presence of chloroquine (data not shown) or bafilomycin (Fig. 1), further arguing against a role of endocytic processing of these epitopes, because cathepsins are only optimally active at acidic pH. Taken together, these data suggest that proteolysis of the four proteasome-independent epitopes is not dependent on endosomal proteases or TPPII.

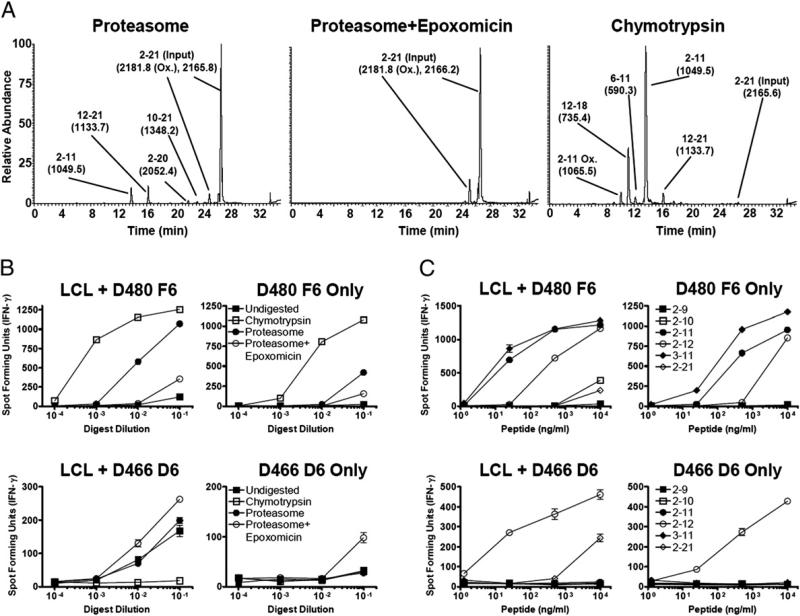

An epoxomicin-enhanced epitope is generated by purified proteasomes

To directly test the possibility that the proteasome is able to generate an epoxomicin-enhanced epitope, an in vitro proteasome model of Ag processing was established. The N terminus of CFP10 was chosen for analysis because it contains both epoxomicin-inhibited [CFP102–9 (Fig. 2), CFP103–11 (17)] and epoxomicin-enhanced [CFP102–12 (Fig. 2)] epitopes. Purified immunoproteasomes were incubated with CFP102–21 in the presence or absence of epoxomicin or chymotrypsin for 20 h. Because there is a predicted chymotrypsin cleavage site between aa 11 and 12, we included chymotrypsin as a control for enzymatic activity that will destroy the 2–12 epitope. The resultant peptides were assessed by LC-MS/MS and T cell-dependent IFN-γ ELISPOT. For T cell assays, the proteasomal digests were pulsed onto LCLs to increase the sensitivity of the assay. Alternately, digests were added directly onto CD8+ T cells to ensure that there was no further processing of peptides.

Incubation of the 20-mer peptide with proteasomes resulted in a modest 15–25% reduction of the parent peptide as estimated by LC-MS/MS (data not shown), whereas chymotrypsin digestion resulted in nearly complete digestion (Fig. 3A). As predicted, chymotrypsin digestion resulted in generation of the CFP102–11 epitope but destroyed the CFP102–12 epitope (Fig. 3A,3B). These data are consistent with proteolysis generating one epitope while destroying another.

FIGURE 3.

CFP102–12 is generated by proteasomes and enhanced by epoxomicin. CFP102–21 (50 μg) was incubated with 5 μg purified 20S immunoproteasomes or chymotrypsin for 20 h, and peptide digests were analyzed by LC-MS/MS and IFN-γ ELISPOT. A, Representative LC-MS/MS analysis of digested peptide. After incubation with proteasomes, 15–25% of the input peptide is degraded, whereas almost complete digestion is seen with chymotrypsin. Peaks are labeled with the appropriate peptide species detected, with the calculated masses in parentheses. Data are representative of two experiments. B and C, Serial dilutions of proteasome digests (B) or synthetic peptides (C) were incubated with CD8+ T cell clones (20,000/well) in the presence (left panels) or absence (right panels) of LCLs (20,000/well) in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Error bars represent the SEM of duplicate wells, and data are representative of two experiments. Ox, oxidized.

We next asked whether the proteasome could generate the epoxomicin-enhanced epitope CFP102–12. We hypothesized that Ag presentation is increased in epoxomicin-treated DCs because of proteasome cleavage within the epitope. After digestion with purified proteasomes, CFP102–11 was readily detectible, as assessed by both IFN-γ ELISPOT and LC-MS (Fig. 3A,3B). Alternately, incubation of CFP102–21 with proteasomes did not result in detectible levels of CFP102–12. When epoxomicin was included, the amount of CFP102–11 was drastically reduced, similar to data from M. tuberculosis-infected DCs. Surprisingly, epoxomicin enhanced the generation of CFP102–12, making it now detectible by T cell assay but not LC-MS. As demonstrated in Fig. 3C, clone D466 D6 only responds to the CFP102–12 minimal epitope in the absence of LCLs to process the extended peptide, showing that the measured response is not to a shorter peptide. When samples were analyzed by MS-MS, CFP102–12 was detected in both proteasome samples (with and without epoxomicin) but not in the undigested or chymotrypsin digested samples, further confirming the presence of this peptide. These data argue that the proteasome is better able to generate CFP102–12 in the presence of epoxomicin and rule out the requirement for an alternate cytosolic protease for generation of CFP102–12. These data also suggest that the proteasome is sufficient for generation of the remaining epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes. Furthermore, the enhancement seen with epoxomicin suggests that competition exists between different proteolytic activities of the proteasome for generation of T cell epitopes.

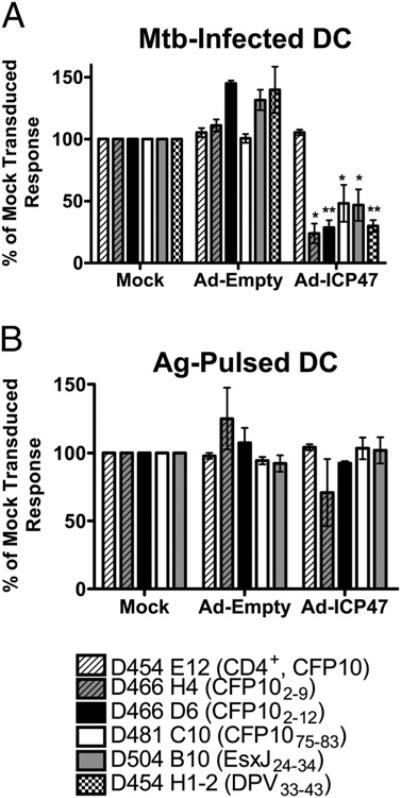

Presentation of epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes requires TAP transport

Having demonstrated a role for ER-Golgi transport and the proteasome in the generation of the epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes, the role of TAP was next examined. We have previously shown that TAP is required for the presentation of the CFP102–11 (18), CFP103–11, and the HLA-E epitopes (17). The HSV-1–encoded protein ICP47 is a potent inhibitor of MHC-I Ag processing via its ability to prevent peptide binding to the cytosolic face of TAP (23, 35). Infection of DCs with an adenovirus vector expressing ICP47 resulted in inhibition of both epoxomicin-inhibited (CFP102–9) and epoxomicin-enhanced (CFP102–12, CFP1075–83, EsxJ24–34, and DPV33–43) epitopes (Fig. 4A). ICP47 had no effect on presentation of cognate peptide to these CD8+ T cell clones (Fig. 4B). In addition, presentation of M. tuberculosis-derived or soluble CFP10 to a CD4+ T cell clone (D454 E12) was not affected (Fig. 4A, 4B). These data demonstrate a requirement for cytosolic transport of all Ags presented to CD8+ T cells tested to date.

FIGURE 4.

TAP transport is required for presentation of all epitopes. DCs were infected with either adenoviral ICP47 or empty vector using Lipofectamine 2000. After 6–26 h, DCs were washed and infected with H37Rv-eGFP (A) or pulsed with Ag (B). Following overnight incubation, T cell clones were added, and IFN-γ production was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining. For each clone, the mean response to mock-treated, M. tuberculosis-infected DCs was at least 4-fold higher than the response to uninfected DCs. Data have been normalized to the untreated controls, and each bar represents the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 using two-tailed Student t test compared with untreated controls. Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Newly synthesized MHC-I is required for Ag presentation

Conventional MHC class I presentation requires new protein synthesis for loading onto nascent MHC molecules in the ER, although the vacuolar presentation pathway is insensitive to cycloheximide treatment (36). Presentation of cytosolically processed CFP103–11 requires newly synthesized HLA-I, because presentation is blocked in the presence of cycloheximide (17). Alternately, presentation of an HLA-E–presented Ag, which is processed cytosolically but loaded within the phagosome, does not require new protein synthesis.

We examined the role of protein synthesis in the presentation of three of the epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes. As shown previously, cycloheximide treatment led to an enhanced presentation of the HLA-E–presented epitope (Fig. 5, Table II). Presentation of the epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes CFP102–12, CFP1075–83, and EsxJ24–34 were inhibited by >70%, demonstrating a requirement for nascent HLA-I. Interestingly, presentation of the epoxomicin-inhibited epitope CFP102–9 was only slightly inhibited in the presence of cycloheximide. Presentation of synthetic peptides was not significantly affected by cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 5). Taken together, these data demonstrate that all M. tuberculosis Ags characterized to date are processed cytosolically.

FIGURE 5.

Protein synthesis is required for presentation of epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes. DCs were treated with cycloheximide (10 μg/ml), infected with H37Rv-eGFP or pulsed with peptide, and used as APCs in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as described in Fig. 1. Data have been normalized to the untreated control, and each bar represents the mean ± SEM of at least three experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 using two-tailed Student t test compared with untreated controls. Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Table II.

Effect of inhibitor treatment on presentation of the indicated epitope

| Epitope | ICP4V | Epoxomicin | Brefeldin A | Bafilomycin | Cycloheximide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFP102–9 | – – – | – – – – | – – – – | 0 | – |

| CFP102–11a | – – – | – – – –b | – – – – | ND | ND |

| CFP103–11a | – – – | – – – – | – – – – | 0 | – – – – |

| CFP102–12 | – – – | + | – – – – | + | – – – – |

| CFP1075–83 | – – – | + | – – – | 0 | – – – |

| DPV33–43 | – – – | + | – – – – | 0 | ND |

| EsxJ24–34 | – – – | + | – – – – | 0 | – – – – |

| Ag85B144–153 | – – – | – – – – | – – – – | – – | ND |

| HLA-E Aga | – – – | – – – – | – – | + | + |

Discussion

There has been considerable interest in the mechanisms by which particulate-associated Ags are processed and presented in the context of the MHC-I pathway. However, much of what is known has been derived using OVA conjugated to a variety of beads or expressed by bacteria, leading to a paucity of data regarding processing of naturally occurring epitopes in biological infections. To define those epitopes generated during the natural course of infection with M. tuberculosis, we have used M. tuberculosis-infected DCs to generate CD8+ T cell clones. In this study, these clones, specific for six recently defined epitopes from four secreted proteins, were used to examine the requirements for MHC-I processing and presentation. Although the effects of inhibitors vary for different epitopes, these data demonstrate that all epitopes examined ultimately require proteasomal degradation, TAP transport, loading onto nascent HLA-I, and ER-Golgi egress. Taken together, these data demonstrate that all of the epitopes use the cytosolic pathway.

Although these and other data corroborate robust use of the cytosolic pathway for presentation of M. tuberculosis Ags on HLA-I (Table II) (17, 18), we have primarily examined secreted proteins. Similarly, secretion of OVA or the endogenous protein, GRA6, into the parasitophorous vacuole by Toxoplasma gondii leads to cytosolic MHC-I presentation (37–40). Conversely, presentation of secreted OVA expressed by Leishmania major is TAP and proteasome independent (40), demonstrating that cytosolic processing of secreted proteins is not absolute. As noncytosolic processing of an M. tuberculosis-derived lipoprotein has been previously described (19), our findings then lead to the hypothesis that M. tuberculosis-secreted proteins may preferentially access the cytosol. In this regard, it is interesting to note the dependence on bacterial secretion of CFP10 for T cell priming (41).

The mechanism(s) by which M. tuberculosis proteins gain access to the cytosol remain to be elucidated. It has been reported that the whole M. tuberculosis bacterium is able to escape the phagosome and reside in the cytosol (42). However, the DCs used in this study were fixed at a time prior to bacterial escape (18 h postinfection), excluding this possibility. As M. tuberculosis expresses several effectors that potentially function in the cytosol [e.g., SapM, PknG, and CFP10 (43–45)], the cytosolic delivery of proteins may be beneficial to the bacterium. However, this comes at the cost of potential detection by CD8+ T cells. Whether M. tuberculosis facilitates translocation of proteins to the cytosol or uses host cell machinery has yet to be determined. The normally ER-localized cellular retrotranslocation machinery can be localized to phagosomes and function in the cytosolic translocation and MHC-I presentation of phagosomal Ags (46). We have demonstrated that the retrotranslocation inhibitor Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A inhibits presentation of two M. tuberculosis epitopes, including one from CFP10 (17), suggesting that host cell machinery plays a role in this process. Furthermore, we and others have demonstrated that an intact region of difference 1 (RD1) is not required for MHC-I presentation of a non-RD1 Ag or priming of M. tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells (18, 47), suggesting that any potential membrane disruptions (42, 48, 49) initiated by the RD1-encoded Esx-1 secretion system are not strictly required for cytosolic access. Although these data implicate the host cell for translocation of M. tuberculosis proteins to the cytosol for Ag presentation, they do not exclude a role for M. tuberculosis-induced translocation. Further analysis is necessary to identify the specific components required for cytosolic access of M. tuberculosis proteins.

The observation that proteasome blockade by epoxomicin resulted in enhanced presentation of four epitopes was surprising. Although inhibition of proteasome function could cause either direct (i.e., lack of protein degradation and proper generation of epitope C termini) or indirect effects (i.e., lack of HLA-I trafficking because of peptide depletion) on Ag presentation, it is hard to imagine a scenario where the indirect effects of proteasome blockade would enhance Ag presentation. Furthermore, we were able to confirm these findings by incubating purified proteasomes with a synthetic extended peptide from CFP10, showing that the proteasome is in fact better at generating CFP102–12 in the presence of epoxomicin. Although there are many possible explanations for this phenomenon, we hypothesize several different scenarios that would lead to the observed enhancement. First, the epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes may not be generated by the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome. Most proteasome inhibitors, including epoxomicin, more potently inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome. Blocking the chymotrypsin-like activity may allow the other proteolytic activities to generate the correct C terminus. This scenario would suggest competition between different proteasome activities for generation of MHC-I–presented peptides, possibly evidenced by the more efficient generation of CFP102–11 versus CFP102–12 in the absence of epoxomicin (Fig. 3). A second possibility is an altered peptide repertoire generated in the presence of proteasome inhibitors. Interestingly, three of the four epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes are 11-mers. This suggests that longer peptide epitopes are inefficiently generated by the fully active proteasome, consistent with previous reports demonstrating that the mean size of proteasome products is <8 aa (50–52). Decreased proteolytic activity in the presence of inhibitors may result in more efficient generation of longer epitopes. Similarly, epitopes may be both generated and then immediately destroyed when the proteasome is fully active. The addition of a proteasome inhibitor may decrease excessive degradation of peptides allowing for more efficient epitope generation. Nonetheless, CFP102–12 (Fig. 3) and the other epoxomicin-enhanced epitopes can be generated by the proteasome in the absence of inhibitors, as evidenced by the high-frequency CD8+ T cell response to these epitopes.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that presentation of all six epitopes occurs via the cytosolic pathway. Thus, the predominant pathway for HLA-I presentation of immunodominant M. tuberculosis Ags relies on cytosolic access and processing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Larry David and the Proteomics Shared Resource for the evaluation of proteasome digests. We thank Dr. Joel Ernst for providing H37Rv-expressing eGFP, Dr. David Johnson for providing adenoviral vectors, and GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals for providing recombinant CFP10.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI048090, National Institutes of Health Contract HHSN266200400081C, a Veterans Affairs Hospitals Merit Review grant, the Portland Veterans Affairs Hospitals Medical Center, and Training Grant EYO7123 from the National Eye Institute (to J.E.G.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BFA

brefeldin A

- DC

dendritic cell

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- HS

human serum

- LCL

lymphoblastoid cell line

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- MHC-I

MHC class I

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Ox

oxidized

- RD1

region of difference 1

- TPPII

tripeptidyl peptidase II

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grotzke JE, Lewinsohn DM. Role of CD8+ T lymphocytes in control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:776–788. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stegelmann F, Bastian M, Swoboda K, Bhat R, Kiessler V, Krensky AM, Roellinghoff M, Modlin RL, Stenger S. Coordinate expression of CC chemokine ligand 5, granulysin, and perforin in CD8+ T cells provides a host defense mechanism against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 2005;175:7474–7483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenger S, Hanson DA, Teitelbaum R, Dewan P, Niazi KR, Froelich CJ, Ganz T, Thoma-Uszynski S, Melian A, Bogdan C, et al. An antimicrobial activity of cytolytic T cells mediated by granulysin. Science. 1998;282:121–125. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keane J, Remold HG, Kornfeld H. Virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains evade apoptosis of infected alveolar macrophages. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2016–2020. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molloy A, Laochumroonvorapong P, Kaplan G. Apoptosis, but not necrosis, of infected monocytes is coupled with killing of intracellular bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1499–1509. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oddo M, Renno T, Attinger A, Bakker T, MacDonald HR, Meylan PR. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis of infected human macrophages reduces the viability of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 1998;160:5448–5454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaible UE, Winau F, Sieling PA, Fischer K, Collins HL, Hagens K, Modlin RL, Brinkmann V, Kaufmann SH. Apoptosis facilitates antigen presentation to T lymphocytes through MHC-I and CD1 in tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1039–1046. doi: 10.1038/nm906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vergne I, Chua J, Singh SB, Deretic V. Cell biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:367–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.114015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho JH, Youn JW, Sung YC. Cross-priming as a predominant mechanism for inducing CD8+ T cell responses in gene gun DNA immunization. J. Immunol. 2001;167:5549–5557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasteiger G, Kastenmuller W, Ljapoci R, Sutter G, Drexler I. Cross-priming of cytotoxic T cells dictates antigen requisites for modified vaccinia virus Ankara vector vaccines. J. Virol. 2007;81:11925–11936. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00903-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang AY, Bruce AT, Pardoll DM, Levitsky HI. In vivo cross-priming of MHC class I-restricted antigens requires the TAP transporter. Immunity. 1996;4:349–355. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmowski MJ, Gileadi U, Salio M, Gallimore A, Millrain M, James E, Addey C, Scott D, Dyson J, Simpson E, Cerundolo V. Role of immunoproteasomes in cross-presentation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:983–990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen L, Sigal LJ, Boes M, Rock KL. Important role of cathepsin S in generating peptides for TAP-independent MHC class I crosspresentation in vivo. Immunity. 2004;21:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigal LJ, Crotty S, Andino R, Rock KL. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to virus-infected non-haematopoietic cells requires presentation of exogenous antigen. Nature. 1999;398:77–80. doi: 10.1038/18038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morón VG, Rueda P, Sedlik C, Leclerc C. In vivo, dendritic cells can cross-present virus-like particles using an endosome-to-cytosol pathway. J. Immunol. 2003;171:2242–2250. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grotzke JE, Harriff MJ, Siler AC, Nolt D, Delepine J, Lewinsohn DA, Lewinsohn DM. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome is a HLA-I processing competent organelle. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000374. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewinsohn DM, Grotzke JE, Heinzel AS, Zhu L, Ovendale PJ, Johnson M, Alderson MR. Secreted proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis gain access to the cytosolic MHC class-I antigen-processing pathway. J. Immunol. 2006;177:437–442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neyrolles O, Gould K, Gares MP, Brett S, Janssen R, O'Gaora P, Herrmann JL, Prévost MC, Perret E, Thole JE, Young D. Lipoprotein access to MHC class I presentation during infection of murine macrophages with live mycobacteria. J. Immunol. 2001;166:447–457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beatty WL, Rhoades ER, Ullrich HJ, Chatterjee D, Heuser JE, Russell DG. Trafficking and release of mycobacterial lipids from infected macrophages. Traffic. 2000;1:235–247. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beatty WL, Russell DG. Identification of mycobacterial surface proteins released into subcellular compartments of infected macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:6997–7002. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6997-7002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beatty WL, Ullrich HJ, Russell DG. Mycobacterial surface moieties are released from infected macrophages by a constitutive exocytic event. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2001;80:31–40. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.York IA, Roop C, Andrews DW, Riddell SR, Graham FL, Johnson DC. A cytosolic herpes simplex virus protein inhibits antigen presentation to CD8+ T lymphocytes. Cell. 1994;77:525–535. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinzel AS, Grotzke JE, Lines RA, Lewinsohn DA, McNabb AL, Streblow DN, Braud VM, Grieser HJ, Belisle JT, Lewinsohn DM. HLA-E–dependent presentation of M. tuberculosis-derived antigen to human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:1473–1481. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewinsohn DA, Heinzel AS, Gardner JM, Zhu L, Alderson MR, Lewinsohn DM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells preferentially recognize heavily infected cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:1346–1352. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-837OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewinsohn DA, Winata E, Swarbrick GM, Tanner KE, Cook MS, Null MD, Cansler ME, Sette A, Sidney J, Lewinsohn DM. Immunodominant tuberculosis CD8 antigens preferentially restricted by HLA-B. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1240–1249. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewinsohn DM, Alderson MR, Briden AL, Riddell SR, Reed SG, Grabstein KH. Characterization of human CD8+ T cells reactive with Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected antigen-presenting cells. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1633–1640. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewinsohn DM, Zhu L, Madison VJ, Dillon DC, Fling SP, Reed SG, Grabstein KH, Alderson MR. Classically restricted human CD8+ T lymphocytes derived from Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected cells: definition of antigenic specificity. J. Immunol. 2001;166:439–446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, Rock KL. A phagosome-to-cytosol pathway for exogenous antigens presented on MHC class I molecules. Science. 1995;267:243–246. doi: 10.1126/science.7809629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chefalo PJ, Harding CV. Processing of exogenous antigens for presentation by class I MHC molecules involves post-Golgi peptide exchange influenced by peptide-MHC complex stability and acidic pH. J. Immunol. 2001;167:1274–1282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarz K, de Giuli R, Schmidtke G, Kostka S, van den Broek M, Kim KB, Crews CM, Kraft R, Groettrup M. The selective proteasome inhibitors lactacystin and epoxomicin can be used to either up- or down-regulate antigen presentation at nontoxic doses. J. Immunol. 2000;164:6147–6157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seifert U, Marañón C, Shmueli A, Desoutter JF, Wesoloski L, Janek K, Henklein P, Diescher S, Andrieu M, de la Salle H, et al. An essential role for tripeptidyl peptidase in the generation of an MHC class I epitope. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:375–379. doi: 10.1038/ni905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guil S, Rodríguez-Castro M, Aguilar F, Villasevil EM, Antón LC, Del Val M. Need for tripeptidyl-peptidase II in major histocompatibility complex class I viral antigen processing when proteasomes are detrimental. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:39925–39934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fonteneau JF, Kavanagh DG, Lirvall M, Sanders C, Cover TL, Bhardwaj N, Larsson M. Characterization of the MHC class I cross-presentation pathway for cell-associated antigens by human dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;102:4448–4455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer D, Tampé R. Herpes viral proteins blocking the transporter associated with antigen processing TAP—from genes to function and structure. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;269:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfeifer JD, Wick MJ, Roberts RL, Findlay K, Normark SJ, Harding CV. Phagocytic processing of bacterial antigens for class I MHC presentation to T cells. Nature. 1993;361:359–362. doi: 10.1038/361359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchard N, Gonzalez F, Schaeffer M, Joncker NT, Cheng T, Shastri AJ, Robey EA, Shastri N. Immunodominant, protective response to the parasite Toxoplasma gondii requires antigen processing in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:937–944. doi: 10.1038/ni.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldszmid RS, Coppens I, Lev A, Caspar P, Mellman I, Sher A. Host ER-parasitophorous vacuole interaction provides a route of entry for antigen cross-presentation in Toxoplasma gondii-infected dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:399–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Shastri N, Turkoz M, Robey EA. Class I major histocompatibility complex presentation of antigens that escape from the parasitophorous vacuole of Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:703–711. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.703-711.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertholet S, Goldszmid R, Morrot A, Debrabant A, Afrin F, Collazo-Custodio C, Houde M, Desjardins M, Sher A, Sacks D. Leishmania antigens are presented to CD8+ T cells by a transporter associated with antigen processing-independent pathway in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. 2006;177:3525–3533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodworth JS, Fortune SM, Behar SM. Bacterial protein secretion is required for priming of CD8+ T cells specific for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen CFP10. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:4199–4205. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00307-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Wel N, Hava D, Houben D, Fluitsma D, van Zon M, Pierson J, Brenner M, Peters PJ. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell. 2007;129:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh B, Singh G, Trajkovic V, Sharma P. Intracellular expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific 10-kDa antigen down-regulates macrophage B7.1 expression and nitric oxide release. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2003;134:70–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vergne I, Chua J, Lee HH, Lucas M, Belisle J, Deretic V. Mechanism of phagolysosome biogenesis block by viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4033–4038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409716102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walburger A, Koul A, Ferrari G, Nguyen L, Prescianotto-Baschong C, Huygen K, Klebl B, Thompson C, Bacher G, Pieters J. Protein kinase G from pathogenic mycobacteria promotes survival within macrophages. Science. 2004;304:1800–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1099384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Cresswell P. A role for the endoplasmic reticulum protein retrotranslocation machinery during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Immunity. 2006;25:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Billeskov R, Vingsbo-Lundberg C, Andersen P, Dietrich J. Induction of CD8 T cells against a novel epitope in TB10.4: correlation with mycobacterial virulence and the presence of a functional region of difference-1. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3973–3981. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Jonge MI, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Fretz MM, Romain F, Bottai D, Brodin P, Honoré N, Marchal G, Jiskoot W, England P, et al. ESAT-6 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis dissociates from its putative chaperone CFP-10 under acidic conditions and exhibits membrane-lysing activity. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:6028–6034. doi: 10.1128/JB.00469-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu T, Hingley-Wilson SM, Chen B, Chen M, Dai AZ, Morin PM, Marks CB, Padiyar J, Goulding C, Gingery M, et al. The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12420–12425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635213100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kisselev AF, Akopian TN, Woo KM, Goldberg AL. The sizes of peptides generated from protein by mammalian 26 and 20 S proteasomes: implications for understanding the degradative mechanism and antigen presentation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:3363–3371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rock KL, York IA, Goldberg AL. Post-proteasomal antigen processing for major histocompatibility complex class I presentation. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:670–677. doi: 10.1038/ni1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toes RE, Nussbaum AK, Degermann S, Schirle M, Emmerich NP, Kraft M, Laplace C, Zwinderman A, Dick TP, Müller J, et al. Discrete cleavage motifs of constitutive and immunoproteasomes revealed by quantitative analysis of cleavage products. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]