Structured Abstract

Study Design

Immunoblotting study to evaluate aggrecan degradation patterns in rat intervertebral discs(IVDs) subjected to mechanical overload.

Objective

To evaluate the effects of in vivo dynamic compression overloading on aggrecan degradation products associated with matrix metalloproteinase(MMP) and aggrecanase activity in different regions of the IVD.

Summary of Background Data

Aggrecan cleavage at the MMP and aggrecanase sites are important events in human IVD aging, with distinct cleavage patterns in the annulus and nucleus regions. No such information is available on regional variations in rat IVDs, nor on how such cleavage is affected by mechanical loading.

Methods

Sprague-Dawley rats were instrumented with an Ilizarov-type device and subjected to dynamic compression (1 MPa and 1 Hz for 8 hours per day for 8 weeks). Control, sham, and overloaded IVDs were separated by disc region and analyzed for aggrecan degradation products using immunoblotting techniques with antibodies specific for the aggrecanase and MMP cleavage sites in the interglobular domain of aggrecan.

Results

Control IVDs exhibited strong regional variation in aggrecan degradation patterns with minimal degradation products being present in the nucleus pulposus(NP), degradation products associated with aggrecanase cleavage predominating in the inner annulus fibrosus(AF), and degradation products associated with MMP cleavage predominating in the outer annulus fibrosus. Dynamic compression overloading increased the amount of aggrecan degradation products associated with MMP cleavage particularly in the AF but also in the NP. Degradation profiles of sham IVDs were similar to control.

Conclusions

Aggrecan G1 regions resulting from proteolysis were found to have a strong regionally-specific pattern in the rat IVD, which was altered under excessive loading. The shift from aggrecanase to MMP-induced degradation products with dynamic compression overloading suggests that protein degradation and loss can precede major structural disruption in the IVD, and that MMP-induced aggrecan degradation may be a marker of mechanically-induced disc degeneration.

Introduction

Intervertebral discs (IVDs) of the spine allow for motion between adjacent vertebrae and are comprised of at least two functionally and compositionally distinct regions: the nucleus pulposus (NP) and the annulus fibrosus (AF), though the demarcation between NP and AF varies with species and the level of disc degeneration. During embryonic development the NP is formed by condensation of notochordal cells whereas the AF is of mesenchymal origin. Most large animals lose notochordal cells with aging and have a more fibrous NP region in mature IVDs. Rodents, rabbits and most small animals retain notochordal cells with aging 1 and maintain a discrete, gelatinous NP into skeletal maturity. The transition between AF and NP is gradual and distinction is often made between inner annulus fibrosus (IAF) and outer annulus fibrosus (OAF). The IAF (or transition region) is of interest in both small and large animal models. The IAF is a region in the IVD with distinct behavior of its tissues and cells from other regions of the IVD 2,3, and exhibits increased cell death and AF disorganization following excessive compression loading in rodents 4.

IVD degeneration is manifested morphologically through a loss in disc height, decreased nucleus volume and a loss of distinction between the NP and AF regions 5. In more severe degeneration, a more extensive loss in IVD structural organization has been noted, with formation of clefts and tears in the NP and AF 6. Degenerative changes on the biochemical level involve degradation of aggrecan with a loss of glycosaminoglycan (GAG), a change in the ratio of type I collagen to type II collagen, and the increased synthesis and activation of matrix degrading enzymes 7, which may initiate the degradative events.

IVD remodeling, degeneration and repair involve a balance between anabolic (i.e., matrix protein production) and catabolic (i.e., matrix protein breakdown) metabolism. Accumulation of degenerative changes can occur when this balance shifts toward catabolic remodeling and biologic repair strategies typically target shifting this balance towards anabolic remodeling 8–10. Accumulation of protein degradation products can provide an early measure of degenerative changes in the IVD. Mechanical loading has significant and specific effects on IVD metabolic responses and matrix remodeling that depends on load type, magnitude, duration and frequency 3,11,12. Dynamic compression loading frequency and magnitude both have the capacity to alter homeostasis towards anabolic or catabolic remodeling 3,13,14. The type of this remodeling response is dictated by changes on the message level but also by the relative activation of proteinases,15 and ultimately changes on the protein level involving protein synthesis, loss, and accumulation of degraded protein products.

Dynamic compression loading chronically applied to tail IVDs of rats led to substantial remodeling 16. Dynamic compression of limited exposure (i.e., short daily duration or for limited time), was consistent with a notion of "healthy" loading that was able to maintain or promote anabolic matrix biosynthesis without substantially disrupting disc structural integrity. In contrast, dynamic compression loading for 8 weeks and 8 hours per day resulted in “overloading” with a slow accumulation of changes similar to human disc degeneration, including loss of IVD height and minor structural disruption 16. Dynamic compression overloading was also associated with upregulation of aggrecan mRNA leading to protein accumulation and an increase in GAG content. This increased aggrecan production may represent an early reparative response to degeneration, but if it occurs within a proteolytic milieu it may also undergo degradation.

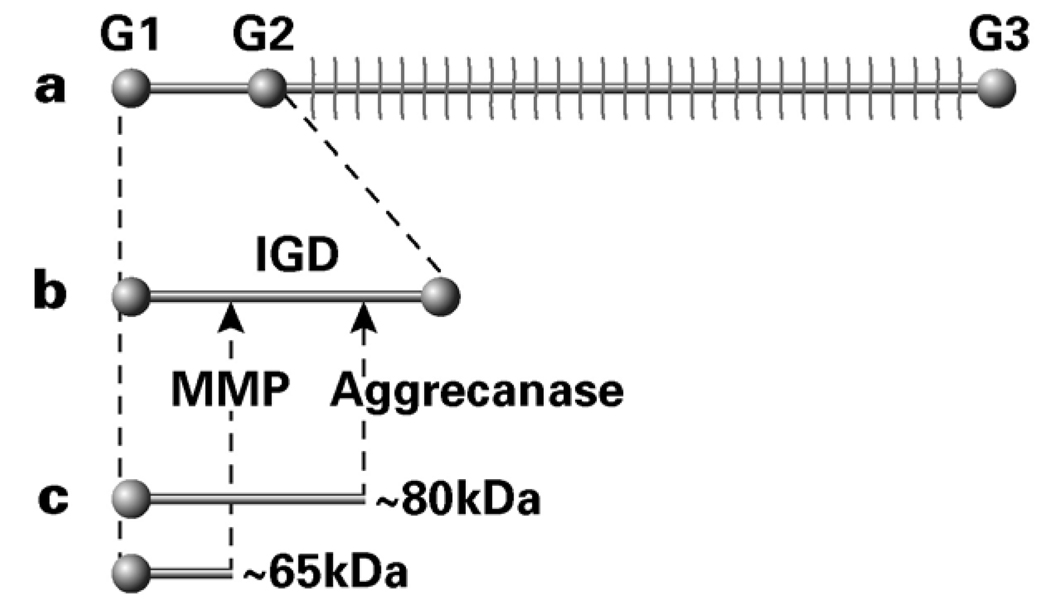

The IVD contains several proteoglycans including aggrecan, versican, decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin, lumican, and perlecan 7. Aggrecan is by far the most abundant proteoglycan in the IVD 17, and the ability of the IVD to resist compression is dependent largely on the concentration of the aggregating proteoglycans that it forms. The aggrecan core protein has three globular regions (G1, G2 and G3) (Figure 1). The interglobular domain (IGD) between the G1 and G2 regions contains cleavage sites vulnerable to enzymatic activity that can remove the abundant GAG chains (between the G2 and G3 regions) from the hyaluronan backbone. Aggrecan degradation can be assessed using immunoblotting techniques that distinguish between matrix metalloproteinase and aggrecanase cleavage in the IGD based on size of the aggrecan fragments. Analysis of human IVD tissue extracts with an antibody recognizing the G1 domain of aggrecan identified degradation products associated with cleavage by both MMP and aggrecanase action 18. Furthermore, there was evidence of an increase in age and degeneration-related accumulation of both degradation products, with the age-related increase in abundance of the MMP-generated degradation products preceding that of the aggrecanase-generated degradation products 18 and the presence of aggrecanase-generated products being at greater levels in advanced degeneration 19. Immunolocalization has demonstrated distinct regional patterns in the presence of MMPs in the NP and AF, which are also affected by degeneration and aging 20,21. Aggrecan degradation products resulting from cleavage at the MMP and aggrecanase sites within the interglobular domain have been described for cartilage and IVD 18,22, though little is known about the ability of mechanical loading to induce their generation.

Figure 1.

The overall hypothesis of this study was that excessive dynamic compression loading that is sufficient to cause early degenerative changes in the IVD (i.e., overloading) will increase aggrecan degradation products and shift the proteolytic mechanism of aggrecan degradation toward MMP-mediated activity. The shift towards MMP-mediated aggrecan degradation in early degeneration is consistent with human studies that found age-related accumulation of degradation products from MMP-activity preceded those from aggrecanase-activity 18. Towards this end, rat tail intervertebral discs were subjected to dynamic compression of 1 MPa and 1 Hz for 8 hours per day for 8 weeks to create IVDs with early accumulation of degeneration due to mechanical overload. This overloading regime might correspond in humans to vibrations or other activities associated with excessive dynamic compression overloading such as operating heavy machinery, training for distance running, or training of elite figure skaters which have been (but are not always) associated with back injury and pain 23–25. Immunoblot analysis of extracts from different regions of control and overloaded rat caudal IVD tissue were then evaluated for the accumulation of aggrecan degradation products to assess the specific contributions from MMPs and aggrecanases in aggrecan G1 region generation.

Materials and Methods

Instrumentation and loading of rat caudal discs

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Twelve week old Sprague-Dawley rats (skeletally mature) were instrumented with an Ilizarov-type device as previously described16,26. Briefly, under general anaesthesia using xylazine (5–10 mg/kg rat) and ketamine (40–80 mg/kg rat) and application of subcutaneous analgesia (buprenorphine, 0.05 mg/kg rat), carbon fiber rings were attached to caudal vertebrae c8 and c9, using sterile 0.8 mm Kirschner wires. The time of surgery was less than 30 minutes per animal, buprenorphine was administered 12, 24, and 36 hours postoperatively, and loading was initiated on post-op day 3. Animals were randomly assigned to loaded or sham groups.

For loaded animals (n=3), a pneumatic loading apparatus 27 applied sinusoidal compression loading with a peak force magnitude of 12.6 N and a minimum of 0 N at a frequency of 1.0 Hz. This force corresponded to an effective stress of approximately 300% body weight (~1 MPa) which was previously shown to influence IVD cell mRNA expression and provide chronic remodeling to IVD composition and structure14,16. The wearable loading apparatus permitted animals to move freely, and eat and drink during loading. Loaded animals had tail IVDs that were subjected to 8 weeks of dynamic compression for 8 hours per day. Animals were sacrificed 24 hours after the last loading cycle and instrumented (c 8–9) discs were harvested and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Under frozen conditions, NP and AF regions were excised as previously described 14 using biopsy punches of 2 and 5 mm diameter to separate 2 distinct regions (NP and AF). Tissue sections remained frozen during the dissection process, and were then stored at −80°C until analyzed.

Sham animals (n=3) had surgically attached rings and were kept under identical conditions for 8 weeks, but did not wear the loading apparatus nor experience any externally applied loading. They were sacrificed at the same time as their loaded counterparts, and tissue was processed in an identical manner.

Isolation of defined regions of the disc from control rats

Control (n=3) IVDs were also obtained from caudal c8–9 levels from Sprague-Dawley rats that were 12 weeks of age, but which had not undergone surgery. To maximize regional distinction in this control group, 2, 4, and 5 mm diameter biopsy punches were used to separate NP, IAF and OAF regions. Tissue was stored at −80°C until analyzed.

Extraction of rat disc tissue

Tissue wet weights typically varied between 2–8 mg, depending on the anatomical region. Irrespective of weight, tissue was extracted with 200 µl of 4 M guanidinium chloride, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, containing proteinase inhibitors (Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets, Roche Diagnostics). Extraction was performed for 48 hr in 1.5 ml microfuge tubes attached to a titer plate shaker to provide continuous agitation to the samples. Extracted proteins were then recovered from the extracts by precipitation at 4°C overnight with 9 volumes of ice cold ethanol. In some cases, biotinylated soya bean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI) was added to the extracts to monitor precipitation. Precipitated protein was washed in ice cold ethanol, dried under vacuum, and resuspended in SDS/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer, so that 100 µl contained the protein extracted from 1 mg tissue and 30 µl of this solution was used for SDS/PAGE.

SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting analysis

Samples of disc extracts were subjected to electrophoresis through NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen), and the fractionated proteins were then electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) at 4°C overnight. The blocked membrane was then incubated at RT for 1 hr with one of three primary rabbit antisera 18, diluted in TBS-T containing 5% skim milk: anti-aggrecan G1, 1:500 dilution; anti-DIPEN, 1:1000 dilution (antibody to C-terminal amino acid sequence of the G1 region generated by MMPs); or anti-NITEGE, 1:500 dilution (antibody to C-terminal amino acid sequence of the G1 region generated by aggrecanases). After washing in TBS-T, membranes were incubate with biotinylated anti-rabbit Ig (1:1000 dilution), then exposed to streptavidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex, followed by ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents, and finally exposed to Hyperfilm (all from Amersham Biosciences).

Results

Effects of dynamic compression on MMP and aggrecanase cleavage products

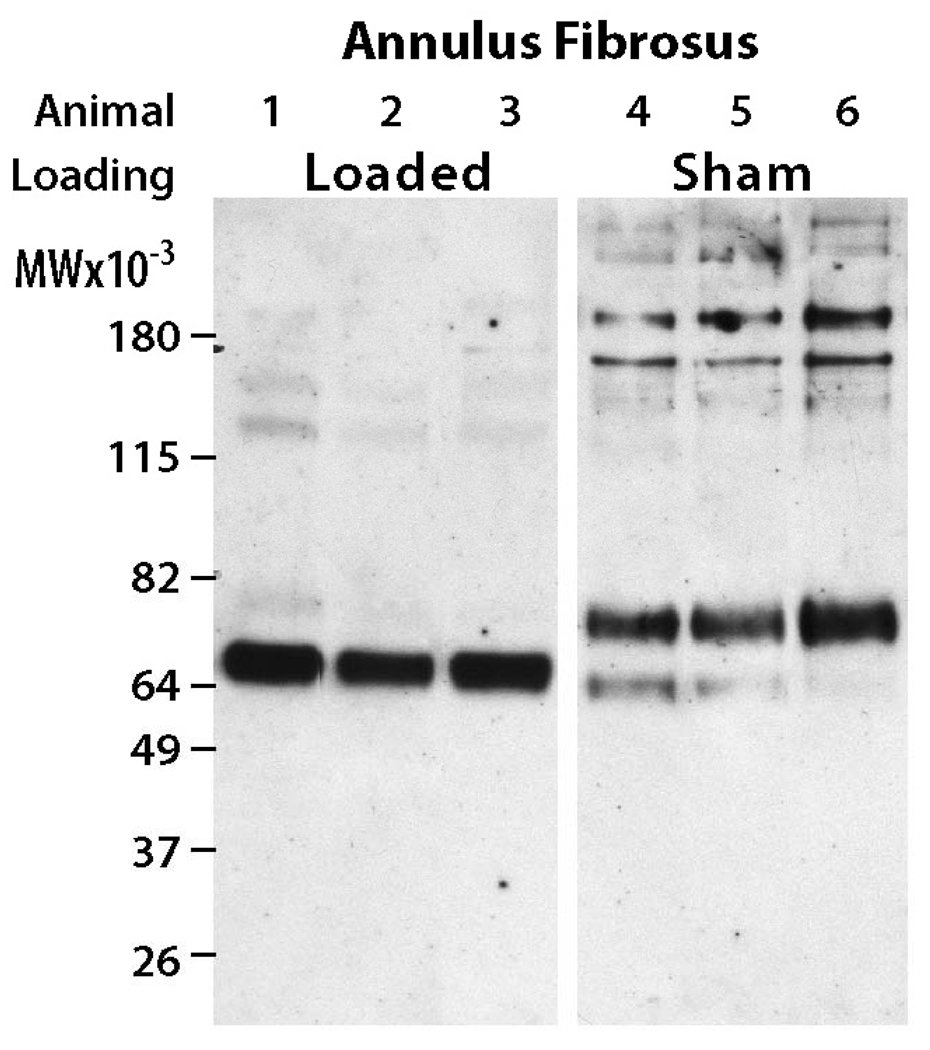

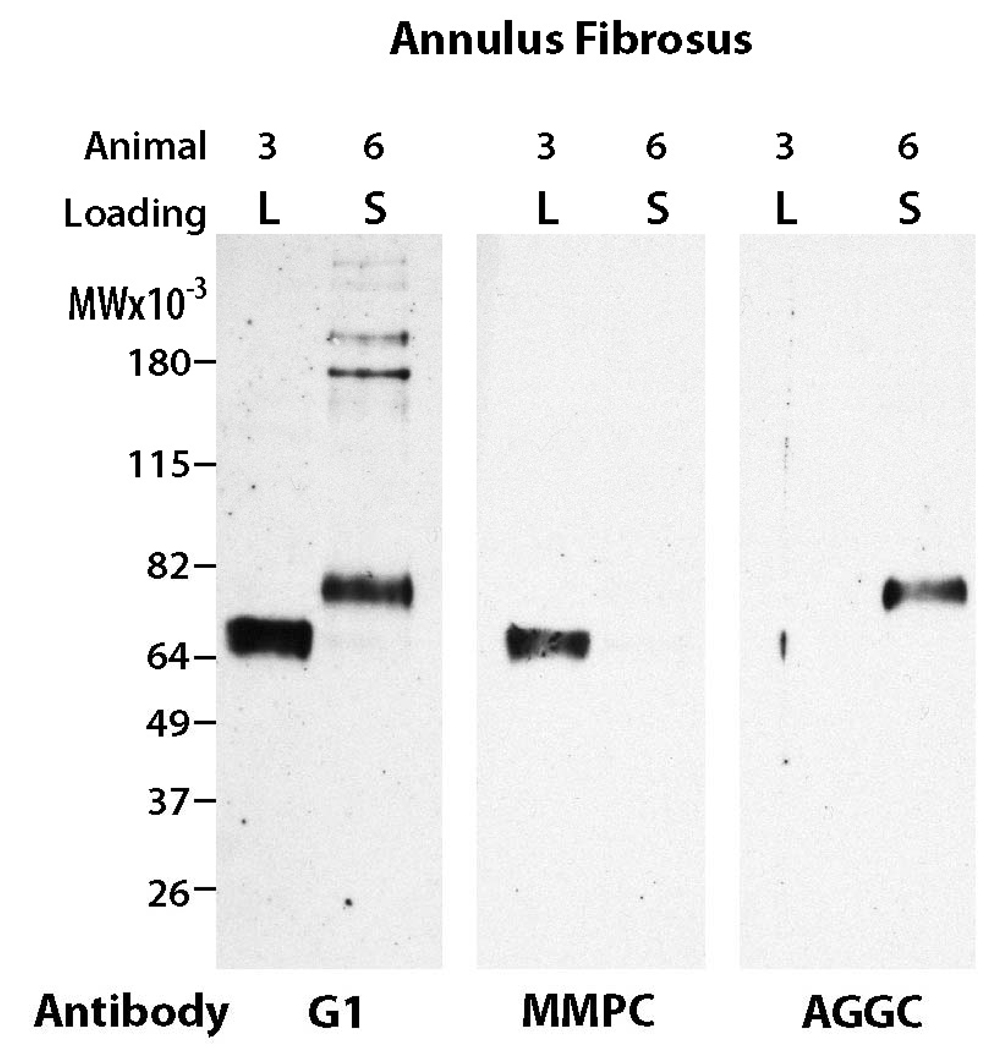

In the AF region, aggrecan G1 regions isolated from overloaded rat caudal IVDs exhibited degradation patterns that were distinct from sham animals (Figure 2). Overloaded IVDs exhibited a predominant aggrecan G1 component with a molecular weight of 64 kDa in all animals. Neoepitope analysis indicated that this product was associated with MMP-mediated degradation of aggrecan (Figure 3). In contrast, the sham IVDs generally exhibited 2 G1 components with molecular weights of 64 and 82 kDa, with the 82 kDa G1 region being most prominent (Figure 2). Neoepitope analysis indicated that the 82 kDa G1 region was associated with aggrecanase-mediated degradation of aggrecan (Figure 3). Thus, compression loading induced a shift in the aggrecan degradation product pattern from predominantly aggrecanase-mediated degradation (82 kDa band) in unloaded discs to predominantly MMP-mediated degradation (64 kDa band) in overloaded discs.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

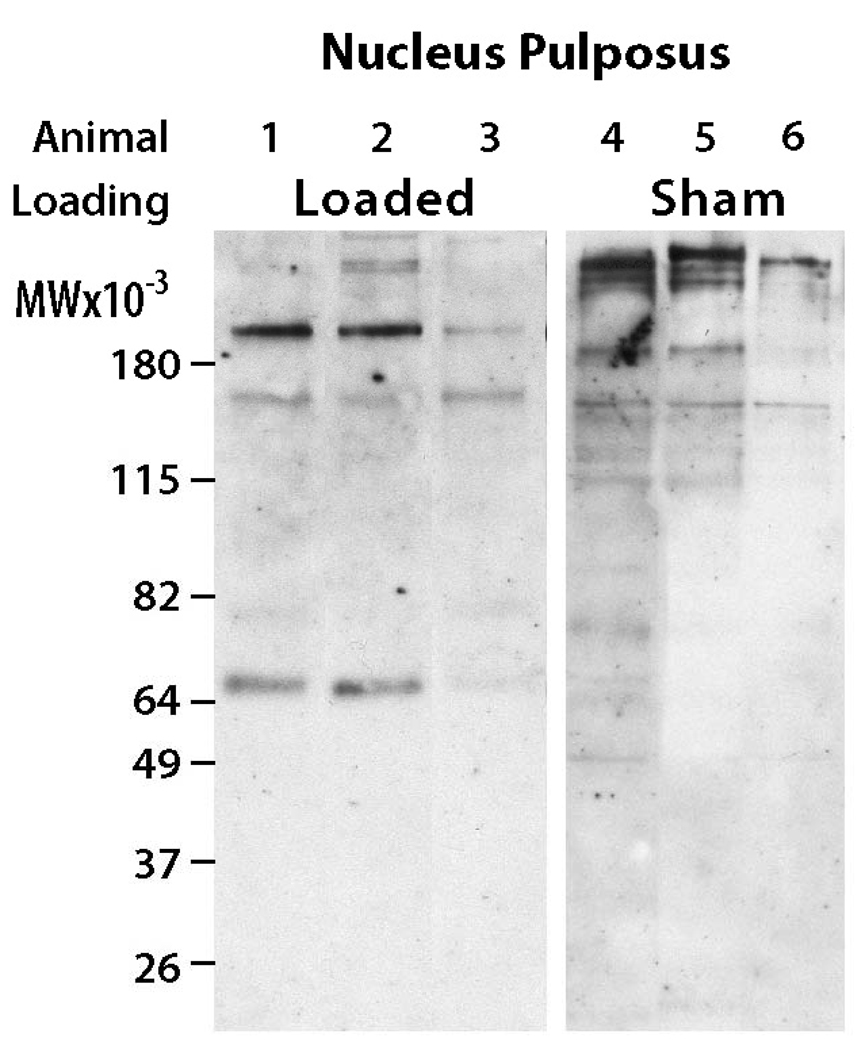

In the NP region, differences in aggrecan degradation products were also observed between the overloaded and sham groups (Figure 4). For the sham animals, there was very little evidence of aggrecan degradation products. However, for the overloaded animals, there was accumulation of aggrecan degradation products with a molecular weight of 64 kDa, which is associated with MMP-mediated degradation. The abundance of this G1 component is much lower than observed in the annulus fibrosus of the same discs.

Figure 4.

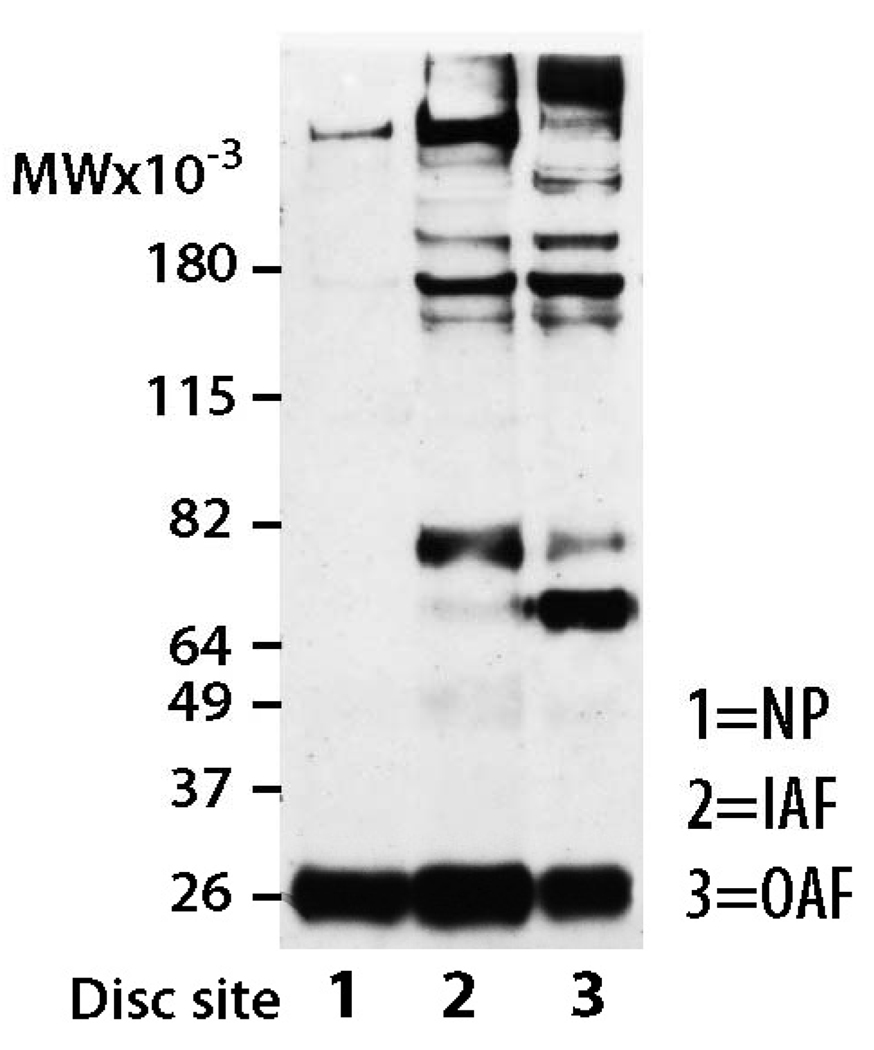

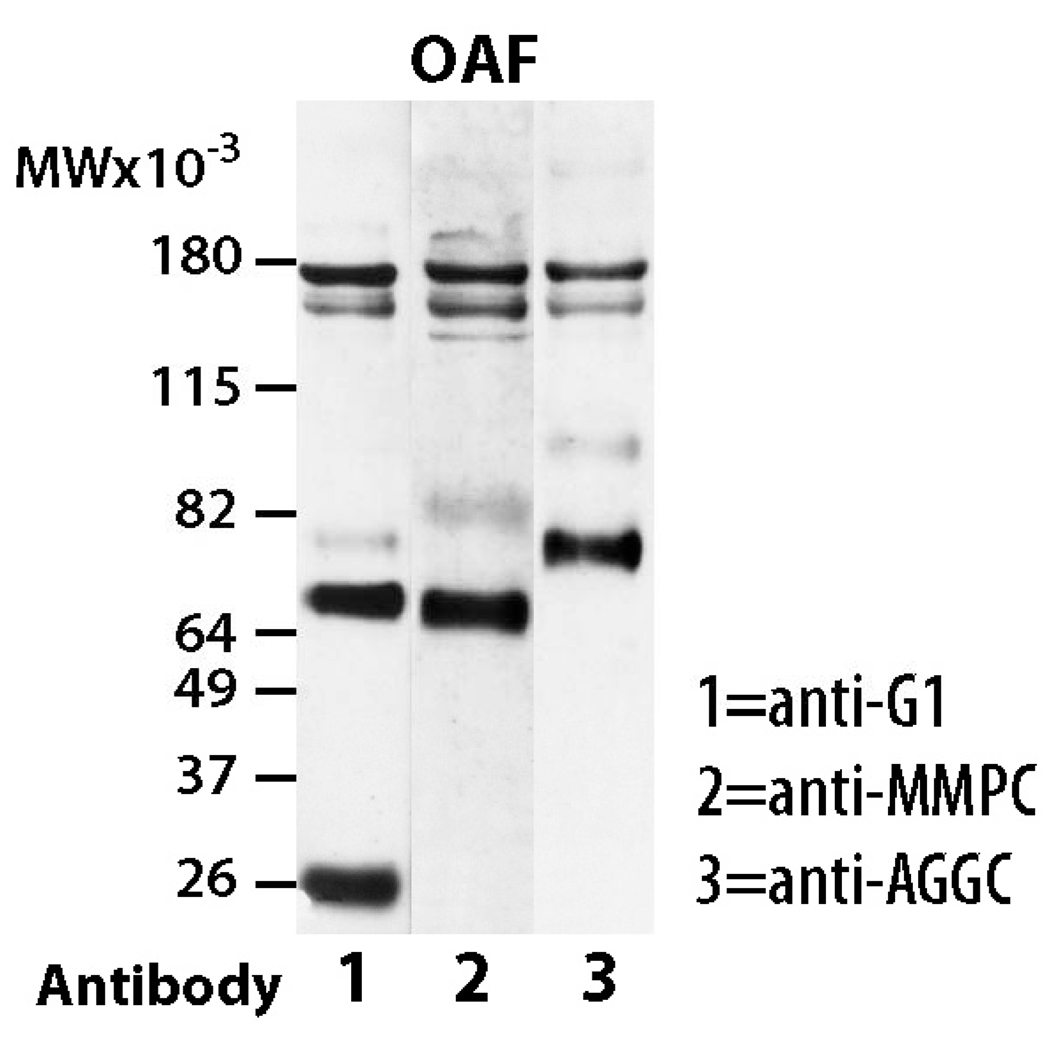

Effects of IVD region on aggrecan degradation product levels

As the sham operated IVDs possessed both MMP and aggrecanase-generated aggrecan degradation products, it was important to establish whether both components were distributed equally thoughout the AF. For this purpose the IVDs from control rats were divided into three regions representing the NP, IAF and OAF.

Analysis of NP, IAF, and OAF regions from control IVD tissue with the anti-aggrecan G1 antibody revealed 2 major immunoreactive proteins with apparent molecular weights of 64 kDa and 82 kDa, whose abundance varied depending on region (Figure 5). The NP from control animals exhibited patterns similar to sham operated animals and possessed very little aggrecan degradation product. The IAF region of control discs possessed a single G1 component of approximately 82 kDa; whereas the OAF region possessed 2 G1 components, a major component at 64 kDa and a minor component at 82 kDa. The identity of the two G1 components in the OAF region was confirmed using anti-neoepitope analysis, with the 82 kDa component being generated by aggrecanase activity and the 64 kDa component being generated by MMP activity (Figure 6). Thus, the aggrecanase and MMP-generated G1 components are not distributed uniformly throughout the rat AF. As expected, the AF of the sham operated animals exhibited patterns similar to control IVDs possessing characteristics of both OAF and IAF regions (i.e., possessing degradation products resulting from both aggrecanase and MMP activity).

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Discussion

The major goal of this study was to evaluate the effects of in vivo dynamic compression overloading on aggrecan degradation in the IVD. Results indicated that 8 weeks 1 MPa and 1 Hz dynamic compression induces changes in the abundance and pattern of aggrecan degradation products in the NP and AF, respectively. In the AF, chronic dynamic compression overloading caused a shift in the pattern of aggrecan degradation products from cleavage due predominantly to aggrecanase activity to cleavage due to MMP activity, consistent with the hypothesis. In the NP, dynamic compression overloading caused some accumulation of aggrecan degradation products associated with MMP activity. Detailed analysis of the effects of IVD region on the accumulation of aggrecan G1 region degradation products in control rat caudal IVD tissue showed a strong regional variation within the AF. The majority of degradation products associated with aggrecanase activity in unloaded discs is in the IAF region, whereas the majority of degradation products associated with MMP activity is in the OAF region. Together, results support the hypothesis that excessive dynamic compression can induce early degenerative changes in the IVD resulting in the accumulation of aggrecan degradation products, and that such degradation is associated with MMP activity, at least at early stages of degeneration. The current findings suggest that early degenerative remodeling due to adverse compression may be more associated with MMP activity than aggrecanase activity.

In the human, degradation products in the AF associated with aggrecanase and MMP activity both increase with aging, while degradation products in the NP were associated more with aggrecanase activity in the young and developing IVD and more with MMP activity in the mature and aging NP 18. Some increase in degradation products from the G1 region associated with MMP activity was observed with advancing degenerative grade 18,19. Furthermore, an aggrecanase knockout mouse model did not protect the animal from development of spontaneous aging-associated intervertebral disc degeneration 28, which is consistent with the concept that MMPs have greater involvement in IVD degeneration. These findings however contrast observations in cartilage, where there is a greater presence of aggrecan degradation products from aggrecanase action in aging cartilage 18, where aggrecanase knockout in mice does prevent progression of osteoarthritis 29.

The current study, which focused on aggrecan degradation as the primary dependent variable measurement, can be compared with prior results which measured mRNA expression, composition, IVD height, and histology 16. Chronic overloading of rat tail IVDs under cyclic compression of 1 MPa and 1 Hz for 8 weeks at 8 hours per day resulted in a general pattern of anabolic remodelling with increased matrix protein mRNA expression and GAG content in the NP, but also with some changes compatible with early catabolic events. Catabolic changes in the NP included a decrease in TIMP-3 and an increase in ADAMTS-4 mRNA. When compared with the accumulation of MMP-induced cleavage of aggrecan in the NP in the current study, the results suggest that the reduction of TIMP-3 message may be more important than the increase in ADAMTS-4 message in leading to aggrecan degradation. Early catabolic changes were more apparent in the AF in prior studies, with loss of GAG and increase in water content 16, which are consistent with the current study demonstrating larger changes in aggrecan degradation products in the AF of chronically overloaded animals. This cleavage separates the GAG-attachment region of the aggrecan from the remainder of the proteoglycan aggregate, and may allow diffusion of the GAG resulting in its loss in the AF region. The accumulation of aggrecan degradation products in both AF and NP regions in the current study confirms that early degenerative changes are occurring in IVDs overloaded by dynamic compression. The sham group resulted in a significant loss of IVD height and water content, and other minor effects that were attributed to immobilization effects 16. However, current findings indicated the sham operation did not alter aggrecan degradation from control IVDs, which supports the concept that immobilization may reduce aggrecan production without a shift in proteolytic mechanisms for aggrecan cleavage.

IVD degeneration can result from different causes including mechanical overloading as well as injury and chemical degradation, as described for animal models 4,30,31. All of these initiators of degeneration are likely to have a distinct pathogenesis and to accumulate degenerative changes in different manners and at different rates. In the current study, moderate overloading from dynamic compression led to minimal structural damage and altered biosynthesis, with one of the most significant signs of early degeneration being aggrecan degradation through MMP activity, which may be associated with reduced TIMP-3 gene expression. Degeneration induced by injuries and chronic accumulation of IVD degeneration in humans are likely to have greater proinflammatory cytokine involvement in the degenerative process 31–33, and may also involve aggrecanase-mediated cleavage of aggrecan in addition to the MMP activity reported here.

In conclusion, aggrecan degradation products from the G1 region were found to have region-specific patterns in the rat IVD and to accumulate with dynamic compression overloading. The shift from aggrecanase to MMP induced degradation products with overloading (particularly in the AF) suggests that MMP-mediated aggrecan degradation may be a consequence of a mechanically induced stress response distinct from the inflammatory-induced stress response associated with aggrecanase-mediated degradation.

Key Points

Aggrecan degradation involving accumulation of the G1 region has strong regional differences in the healthy rat IVD associated with both aggrecanase and MMP activity.

Accumulation of aggrecan degradation products in the control outer AF exhibited evidence of predominantly MMP activity, while the inner AF exhibited evidence of predominantly aggrecanase activity, and the NP had little evidence of aggrecan degradation products.

Cyclic compression overloading of 1 MPa & 1 Hz applied to caudal IVDs for 8 hour per day for 8 weeks resulted in an increase in accumulation of aggrecan degradation products associated with cleavage of aggrecan by MMP activity.

In the AF, compression overloading caused a shift from degradation products that were predominantly associated with aggrecanase activity in sham animals to degradation products associated with MMP activity in loaded animals.

In the NP region, there was no accumulation of aggrecan degradation products associated with cleavage in the interglobular domain in sham animals, but accumulation of aggrecan degradation products from MMP activity occurred in some of the overloaded animals.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported by Grant Number R01 AR051146 from the National Institutes of Health and Grant Number 8680 from the Shriners of North America. We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Jeffrey MacLean and Ana Barbir with animal procedures, Tatiana Lobanok with the immunoblotting, and Ian Stokes and Devina Purmessur for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hunter CJ, Matyas JR, Duncan NA. Cytomorphology of notochordal and chondrocytic cells from the nucleus pulposus: a species comparison. J Anat. 2004;205:357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruehlmann SB, Rattner JB, Matyas JR, Duncan NA. Regional variations in the cellular matrix of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc. J Anat. 2002;201:159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setton LA, Chen J. Mechanobiology of the intervertebral disc and relevance to disc degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 Suppl 2:52–57. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lotz JC. Animal models of intervertebral disc degeneration: lessons learned. Spine. 2004;29:2742–2750. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146498.04628.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilke HJ, Rohlmann F, Neidlinger-Wilke C, Werner K, Claes L, Kettler A. Validity and interobserver agreement of a new radiographic grading system for intervertebral disc degeneration: Part I. Lumbar spine. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:720–730. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams MA, Roughley PJ. What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it? Spine. 2006;31:2151–2161. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231761.73859.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roughley PJ. Biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration: involvement of the extracellular matrix. Spine. 2004;29:2691–2699. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146101.53784.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson JW, 3rd, Levicoff EA, Gilbertson LG, Kang JD. Biologic modification of animal models of intervertebral disc degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 Suppl 2:83–87. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuda K, An HS. Prevention of disc degeneration with growth factors. Eur Spine J. 2006;15 Suppl 3:S422–S432. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0149-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami H, Yoon ST, Attallah-Wasif ES, Tsai KJ, Fei Q, Hutton WC. The expression of anabolic cytokines in intervertebral discs in age-related degeneration. Spine. 2006;31:1770–1774. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000227255.39896.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iatridis JC, MacLean JJ, Roughley PJ, Alini M. Effects of mechanical loading on intervertebral disc metabolism in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 Suppl 2:41–46. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotz JC, Chin JR. Intervertebral disc cell death is dependent on the magnitude and duration of spinal loading. Spine. 2000;25:1477–1483. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasra M, Merryman WD, Loveless KN, Goel VK, Martin JD, Buckwalter JA. Frequency response of pig intervertebral disc cells subjected to dynamic hydrostatic pressure. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1967–1973. doi: 10.1002/jor.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maclean JJ, Lee CR, Alini M, Iatridis JC. Anabolic and catabolic mRNA levels of the intervertebral disc vary with the magnitude and frequency of in vivo dynamic compression. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:1193–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh AH, Lotz JC. Prolonged spinal loading induces matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in intervertebral discs. Spine. 2003;28:1781–1788. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083282.82244.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wuertz K, Godburn K, Maclean JJ, Barbir A, Stinnett Donnelly J, Roughley PJ, Alini M, Iatridis JC. In vivo remodeling of intervertebral discs in response to short- and long-term dynamic compression. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1235–1242. doi: 10.1002/jor.20867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roughley PJ, Melching LI, Heathfield TF, Pearce RH, Mort JS. The structure and degradation of aggrecan in human intervertebral disc. Eur Spine J. 2005;15 Suppl 3:S326–S332. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0127-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sztrolovics R, Alini M, Roughley PJ, Mort JS. Aggrecan degradation in human intervertebral disc and articular cartilage. Biochem J. 1997;326(Pt 1):235–241. doi: 10.1042/bj3260235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel KP, Sandy JD, Akeda K, Miyamoto K, Chujo T, An HS, Masuda K. Aggrecanases and aggrecanase-generated fragments in the human intervertebral disc at early and advanced stages of disc degeneration. Spine. 2007;32:2596–2603. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158cb85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruber HE, Ingram JA, Hanley EN., Jr Immunolocalization of MMP-19 in the human intervertebral disc: implications for disc aging and degeneration. Biotech Histochem. 2005;80:157–162. doi: 10.1080/10520290500387607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiler C, Nerlich AG, Zipperer J, Bachmeier BE, Boos N. 2002 SSE Award Competition in Basic Science: expression of major matrix metalloproteinases is associated with intervertebral disc degradation and resorption. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:308–320. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flannery CR, Lark MW, Sandy JD. Identification of a stromelysin cleavage site within the interglobular domain of human aggrecan. Evidence for proteolysis at this site in vivo in human articular cartilage. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1008–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakker EW, Verhagen AP, van Trijffel E, Lucas C, Koes BW. Spinal mechanical load as a risk factor for low back pain: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:E281–E293. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318195b257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubravcic-Simunjak S, Pecina M, Kuipers H, Moran J, Haspl M. The incidence of injuries in elite junior figure skaters. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:511–517. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:95–101. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacLean JJ, Roughley PJ, Monsey RD, Alini M, Iatridis JC. In vivo intervertebral disc remodeling: kinetics of mRNA expression in response to a single loading event. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:579–588. doi: 10.1002/jor.20560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stinnett-Donnelly J, MacLean J, Iatridis J. Removable Precision Device for In-Vivo Mechanical Compression of Rat Tail Intervertebral Discs. J Med Devices. 2007;1:56–61. doi: 10.1115/1.2355692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, Allen K, LJing L, Tang R, King I, Malfait AM, Setton LA. ADAMTS (Aggrecanase-1) knockout mice are not protected from spontaineous aging-associated intervertebral disc degeneration. Transations of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. 2009 Paper 35. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majumdar MK, Askew R, Schelling S, Stedman N, Blanchet T, Hopkins B, Morris EA, Glasson SS. Double-knockout of ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 in mice results in physiologically normal animals and prevents the progression of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3670–3674. doi: 10.1002/art.23027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iatridis JC, Michalek AJ, Purmessur D, Korecki CL. Localized Intervertebral Disc Injury Leads to Organ Level Changes in Structure, Cellularity, and Biosynthesis. Cellular Molecular Bioeng. 2009;2:437–447. doi: 10.1007/s12195-009-0072-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulrich JA, Liebenberg EC, Thuillier DU, Lotz JC. ISSLS prize winner: repeated disc injury causes persistent inflammation. Spine. 2007;32:2812–2819. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815b9850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JH, Studer RK, Sowa GA, Vo NV, Kang JD. Activated macrophage-like THP-1 cells modulate anulus fibrosus cell production of inflammatory mediators in response to cytokines. Spine. 2008;33:2253–2259. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318182c35f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Maitre CL, Hoyland JA, Freemont AJ. Catabolic cytokine expression in degenerate and herniated human intervertebral discs: IL-1beta and TNFalpha expression profile. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R77. doi: 10.1186/ar2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]