Abstract

Background and aims of study

We have previously demonstrated a requirement for the presence of a juvenile thymus for the induction of transplantation tolerance to renal allografts by a short-course of calcineurin inhibition in miniature swine. We have also shown that aged, involuted thymi can be rejuvenated when transplanted as vascularized thymic lobes into juvenile swine recipients. The present studies were aimed at elucidating the extrinsic factors facilitating this restoration of function in the aged thymus. In particular, we tested the impact of sex steroid blockade by Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH).

Materials and Methods

30 naive animals (25 males and 5 females) were used for measurement of serum testosterone levels. 3 mature male pigs (aged at 22, 22 and 29 months old) were used to test the effects of Lupron (LHRH analog) injection at 45 mg (per 70–80kg body weight) as a 3-month depot on testosterone levels and thymic rejuvenation. Thymic rejuvenation was assessed by histology, flow cytometric analysis, morphometric analysis and TREC assays.

Results

Hormonal alterations were induced by Lupron and resulted in macroscopic and histologic regeneration of the thymus of aged animals within 2 months, as evidenced by restoration of juvenile thymus architecture and increased cellularity. Two animals that were evaluated for TREC both showed increased levels in the periphery following Lupron treatment.

Conclusion

Treatment of aged animals with Lupron leads to thymic rejuventaion in adult miniature swine. This result could expanding the applicability of thymus-dependent tolerance-inducing regimens to adult recipients.

Keywords: LHRH agonist, Thymus, Aging, Rejuvenation, Miniature swine

Introduction

The thymus plays a central role in the development of immunologic tolerance, primarily through screening against self reactivity in newly arising T cells by contact with dendritic cells and peripheral antigens expressed in medullary epithelium using the aire transcription factor. Similarly, central transplantation tolerance to donor antigens following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation occurs through negative selection by donor dendritic cells in the host thymus. We have studied the role of thymus in transplantation tolerance extensively utilizing MHC inbred miniature swine. Our previous results indicated that the presence of a juvenile thymus is essential for the rapid induction of the stable thymic-dependent tolerance that occurs under the influence of a short-course of calcineurin inhibitors following allogeneic renal transplantation. We have also shown that thymic structure and function decline with age, resulting in an inability to induce tolerance as well as to regenerate normal T cell numbers after T cell depletion.

We have recently established a procedure for vascularized thymic lobe transplantation in swine that permits the transplanted thymus to function immediately after revascularization. Utilizing this procedure, we have reported that the aged, involuted thymic lobe grafts were rejuvenated when transplanted into MHC matched juvenile recipients, suggesting that thymic function is largely controlled by the host environment rather than by the local thymic milieu. However, it remained unclear whether a single extrinsic factor alone could induce thymic rejuvenation. In order to investigate a potential extrinsic factor that could be applied clinically, we examined whether the exogenous administration of Lupron, an LHRH agonist, reversed the natural involution process of the thymus in mature swine. This information could have practical implications for expanding the applicability of thymus-dependent tolerance-inducing transplantation protocols to include adults by rejuvenation of the host thymus.

Materials and Methods

1) Animals

MGH miniature swine represent one of the few large animal species in which breeding characteristics make genetic experiments possible. 30 naive animals (25 males and 5 females) were used for measurement of serum testosterone levels. 3 mature male pigs (aged at 22, 22 and 29 months old) were used to test the effects of Lupron injection on testosterone levels and thymic rejuvenation. These 3 animals were sacrificed at 6 months after LHRH analog (Lupron supplied by Norwood Immunology Inc. Victoria, Australia) injection.

2) Surgical Procedures

Thymus biopsy

Thymic biopsies were carried out at day 0, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months and 6 months following Lupron injection. Approximately 1 x 0.5 x 0.5 cm of thymic tissue was biopsied for histology, morphometric and flow cytometric analyses. Tissues for histology were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Coded samples were examined through a light microscope by a pathologist.

3) Evaluation of thymic rejuvenation/involution

a) Preparation of thymocytes and peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs)

Biopsied tissue from thymic grafts (100–200 mg) was finely minced in HBSS buffer; the cell suspension was then filtered through a 200 μm nylon mesh. For separation of PBLs, freshly heparinized whole blood was diluted 1:2 with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and the mononuclear cells were obtained by gradient centrifugation using lymphocyte separation medium (Organon Teknika, Durham, NC) as previously described.

b) Flow cytometry

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of peripheral PBLs was performed using a Becton-Dickinson FACScan (San Jose, CA) with CellQuest FACStation software (Becton Dickinson) as previously reported. Phenotypic analysis of cells was attained by three-color staining with directly conjugated murine anti-swine mAbs, which were the same as those used for immunohistochemistry (see below). The staining procedure was performed as follows: 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in flow cytometry buffer (HBSS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% NaN3) and were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with saturating concentrations of a FITC-labeled mAb. After two washes, the secondary phycoerythrin-conjugated mAb was added and cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. After a further wash, the final biotinylated Ab was added and incubated for 30 min. The cells were washed, and cytochrome was added for an 8-min incubation to stain the biotinylated Ab. Cells were washed twice and then analyzed.

c) Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) used for phenotypic characterization of cell populations in thymic tissue and peripheral blood lymphocytes

Thymocyte development was assessed by immunohistochemistry and FACS analyses using the murine anti-swine mAbs 74-12-4 (IgG2b, anti-swine CD4), 76-2-11 (IgG2a, anti-swine CD8), 76-7-4 (IgG2a, anti-swine CD1) and anti CD45 RA (IgG1) as previously reported.

d) Morphometric analysis

Morphometric studies were performed on thymic biopsy samples using NIH Image (Scion Image, Federick, MD) software. Biopsy samples with at least 15 lobules were stained with H&E and the areas of the cortex and medulla were measured to obtain a ratio of the cortical area to the medullary area (c/m ratio) in the cross-section of the thymus. An increase in this ratio indicated an increase in the degree of rejuvenation of the thymus.

e) Quantification of signal joining (sj) TREC in miniature swine

DNA was isolated from PBLs using DNeasy cell and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA concentration was determined using Nano-drop spectrophotometer instrument. The sj TREC was quantified using Stratagene Mx 3005 system. A total of 25ul reaction, included: DNA template, 800nM of ψJα forward primer: 5′- TCTAAAGAGGAAGAACAAGGTTGGCG -3′, 800nM of δ-Rec reverse primer: 5′-TGTGCAAAGCTGTGAAATGCTCCC-3′ with 200 nM of labeled probe: 5′-/56-FAM/ATGCAGGAGGGCCACGAGTGAAGAGCAGACAGA/ 36-tamsP/-3′and 2x Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Cycling conditions included 95°C for 15min, 94°C for 30s, 60°C for 30s, and 72°C for 45s. sjTREC quantification was based on amplification of a plasmid reference standard. The results were expressed as frequencies (number of sjTREC per ug tissue of genomic DNA).

Results

(1) Testosterone levels in naïve miniature swine

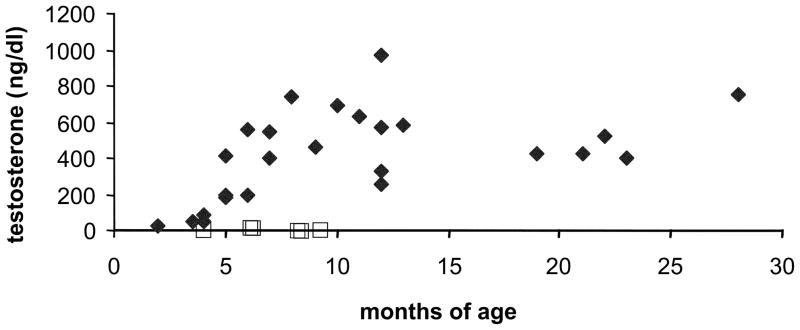

We first measured serum testosterone levels in MGH miniature swine to determine if the levels changed with age. Testosterone levels in twenty-five male swine of different ages are shown in Figure 1. The levels start increasing at 5–6 months of age and were consistently higher than 200ng/ml thereafter (indicated with closed diamonds in Fig. 1). The testosterone levels in 5 female MGH miniature swine were undetectable at less than 20ng/dl independent of age (indicated with square in Fig. 1). Because testosterone levels from female pigs, as shown in Figure 1, were very low pre-Lupron injection, further analysis was limited to males.

Figure 1.

Testosterone levels in naïve miniature swine as a function of age. Male testosterone levels are indicated by the diamond, female levels are indicated by the open square.

(2) Effects of Lupron injection on testosterone levels and thymic rejuvenation

Our recent study indicated that thymic involution assessed by histology and morphmetric analysis was seen after 20 months of age in MGH miniature swine. In addition, the results in this study demonstrated that testosterone levels in male MGH miniature swine plateau after 6-months of age. Based upon these data, we chose three naïve male miniature swine at 22–29 months of age to test whether the administration of the LHRH agonist Lupron could reverse the process of thymic involution associated with aging. At the time of Lupron injection, when the first pig #15630 was 29 months old, it weighed 90 kg; when the second pig #15959 was 22 months old, it weighed 77 kg; and when the third pig #16254 was 22 months old, it weighed 87kg. Lupron was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 45 mg (a 3-month depot) to each pig. Previous studies by other groups that examined the use of LHRH agonists to induce medical castration with a short follow-up period (28 days), suggested that a higher dose of Lupron would be required in swine compared to the clinical human dose. In an attempt to maximize the effect, we chose a similar dose to the previous report, but used a 3-month depot formula, similar to the clinical method of administration.

(a) No clinical side effects of Lupron were seen at the high-dose therapy

Since the dose used in this study was twice as high as the human clinical dose (-3 month 22.5mg for prostate cancer), we carefully monitored liver and kidney function as well as the daily health condition in these three animals throughout the experimental period. As shown in Table 1, no obvious changes in liver enzyme and creatinine levels were seen following high-dose Lupron injection.

Table 1.

Analysis of serum chemistries in three animals after Lupron injection. All three animals maintained normal liver and renal function at all time points after Lupron injection.

| Animals | Timing | AST (U/l) | ALT (U/l) | Total Bil (mg/dl) | Creatinine (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #15630 | Before | 37 | 30 | <0.1 | 1.5 |

| 2 weeks post | 36 | 32 | <0.1 | 1.5 | |

| 1 month post | 16 | 32 | <0.1 | 1.4 | |

| 2 months post | 34 | 39 | 0.2 | 1.4 | |

| 6 months post | 72 | 59 | <0.1 | 1.5 | |

| 15959 | Before | 56 | 38 | <0.1 | 1.3 |

| 2 weeks post | 46 | 40 | 0.3 | 1.1 | |

| 1 month post | 35 | 49 | <0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 2 months post | 34 | 48 | <0.1 | 1.1 | |

| 6 months post | 47 | 86 | <0.1 | 1.0 | |

| 16254 | Before | 33 | 91 | <0.1 | 1.1 |

| 2 weeks post | 49 | 79 | 0.3 | 1.2 | |

| 1 month post | 21 | 54 | <0.1 | 1.1 | |

| 2 months post | 31 | 54 | 0.1 | 1.2 | |

| 6 months post | 49 | 59 | 0.1 | 1.5 |

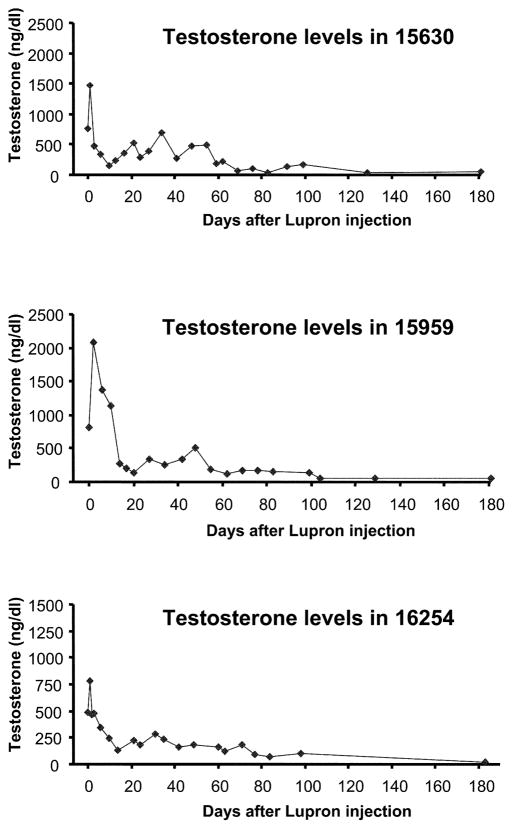

(b) Testosterone levels decreased markedly following Lupron therapy in mature male pigs

Testosterone levels in all three mature pigs markedly increased in the first 2 days following the single injection of high-dose Lupron as a result of the surge induced by the initial rapid increase in LHRH; 1478ng/dl from 752ng/dl in pig #15630, 2073ng/dl from 803ng/dl in pig #15959, and 779ng/dl from 491ng/dl in pig #16254 (Fig. 2). These levels decreased to below baseline values within 10 days and continued to decline over the next 30 days, but did not reach female testosterone levels until 2 months after the injection (20ng/dl). Thereafter, testosterone levels approximated those of female pigs. Levels at 6-months were 43ng/dl (day 181) in #15630, 44ng/dl (day 181) in #15959 and 20ng/dl (day 183) in #16254. This effect was maintained for up to six months, until these animals were sacrificed as scheduled.

Figure 2.

Testosterone levels in three pigs that received Lupron injection. All three animals treated with Lupron demonstrated a transient increase in testosterone in the first 72 hours. By the second month, all animals had a marked decrease in testosterone levels and maintained low levels until the termination of the experiment at 6 months.

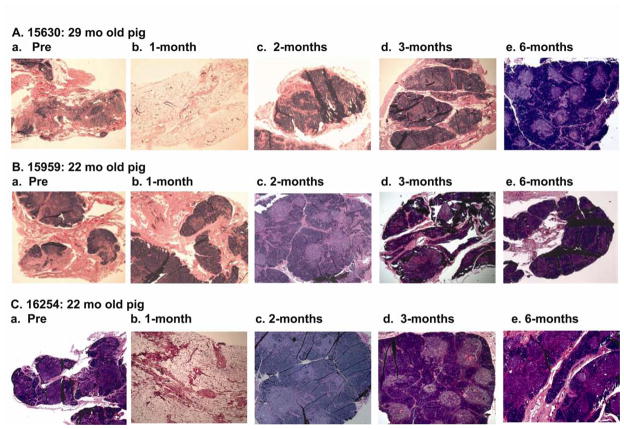

(c) Histologic analysis showed rejuvenation of involuted thymus following Lupron therapy

In order to evaluate Lupron’s effects on the thymus, biopsy specimens were divided for histology, morphmetric anailysis and FACS examination.

Before Lupron injection, histology of the thymus in these three mature swine showed, in comparison to young thymi, a hypocellular and atrophic structure (i.e. thin cortical area with fatty changes), indicating that thymus has undergone involution. The thymus of the 29 month old pig (#15630. Fig. 3A-a) was more hypocellular than those of the 22-month old pigs (#15959 and #16254. Fig. 3B-a and 3C-a). One month following Lupron injection, histology of the thymus in #15630 and #16254 showed severe fatty degeneration, suggesting further thymic involution, possibly as a direct consequence of the initial surge in testosterone (See Discussion), (Fig 3A-a vs. 3A-b, and Fig. 3C-a vs. 3C-b). Since one side of the cervical thymus was macroscopically atrophic, we also examined the other cervical lobe during the biopsy to avoid any sampling error and both thymic lobes were found to be equally atrophic. The thymus in the other animal (#15959) did not show further involution at the one month biopsy, but remained atrophic.

Figure 3.

Histology of thymic biopsy (HE). A) Thymus of 29 month-old male pig # 15630 prior to Lupron injection (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (c), 3 months after (e) and 6 months after injection. B and C) Thymus of 22 month-old male pigs # 15959 and 16254 respectively prior to Lupron injection (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (c), 3 months after (e), and 6 months after injection. Animals #15630 and #16254 had increased atrophy at 1 month, but all animals had rejuvenation of thymic architecture at 2 months that was durable until 6 months after Lupron injection.

At 2 months following Lupron injection, the thymus biopsies showed rejuvenation both grossly and histologically. The cervical thymic lobe in animal #15630 was slightly thicker (3mm thickness) at 2 months than that seen at 1-month (1mm thickness) and also slightly thicker than pre Lupron injection (2mm thickness). The findings were similar in both 22-month old animals, although the thymus in one of 22-month old pigs (#15959) did not further involute at one month post-Lupron. The histology specimens supported the gross findings. Thymic lobules expanded with an increase in cellularity as shown in Fig 3A-c, B-c and C-c. The cortical area of the thymus increased in size with a decrease in interlobular space, suggesting active rejuvenation. Thymus at the 3 month biopsy was similar to that seen at 2 months and the histology specimen also showed similar findings to those seen at 2 months (Fig 3A-d, B-d, C-d), and a similar thymic structure was observed at 6 months, although a slight decrease in the cortical zone and a more obvious medullary zone were noted (Fig 3A, B, C-e). These findings suggested that thymic rejuvenation had started by 2 months following high-dose Lupron injection and continued for 4 months.

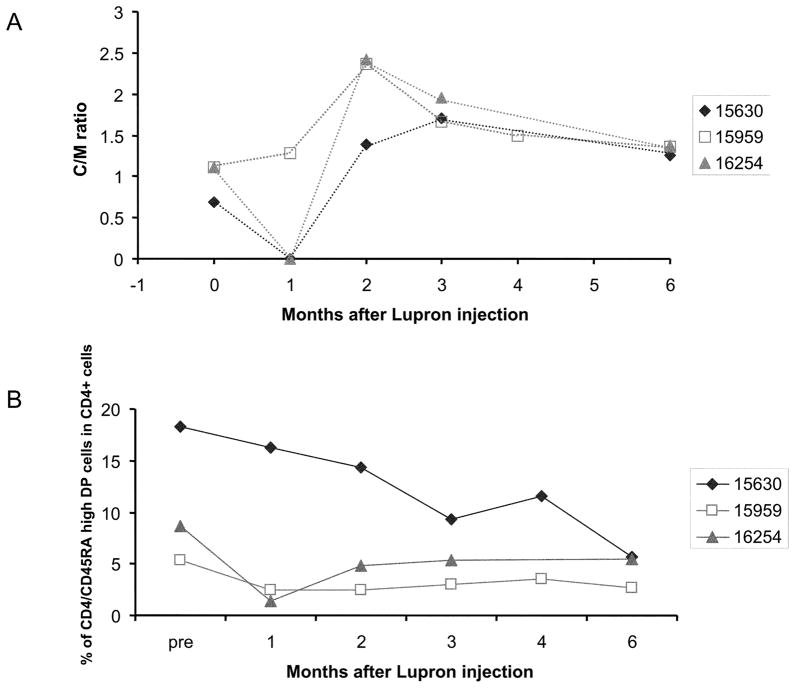

(d) Morphometric study for evaluation of rejuvenation after Lupron injection supported histologic findings

To assess the effects of Lupron on aged porcine thymus, morphometric analysis of the thymus was performed using the NIH Image software on histology photos taken at 40 times magnification. We calculated the ratio of the area of the whole cortex to the area of the whole medulla in every specimen from both animals.

The cortex to medulla (c/m) ratio was 0.69 in #15630, 1.12 in #15959 and 1.11 in # 16254 before Lupron injection. These ratios are representative of those seen in age-matched miniature swine reported previously. Although the ratio was not available at 1 month in #15630 and #16254 because of marked degeneration of the thymus, it increased to 2.03 in #15630, 2.37 in #15959 and 2.42 in #16254 at 2-months after injection. Ratios seen in both 22-month old animals (at time of Lupron injection) were similar to that seen at 4-5 months of age in naive miniature swine. The increased ratio suggests that the thymus in the 22-month old animals seemed to be more sensitive to the Lupron effect as compared to that in the 29-month old animal. Although this ratio started to decrease at 3 months after injection in all three animals, it remained higher at 6 months after injection than before injection (Fig. 4A). These findings indicate that peak thymic rejuvenation was seen 2 months following Lupron injection. As we aimed to test rejuvenation of the thymus and thus designed to end the study after 6 months, we could not determine the period required for the full re-involution in this study.

Figure 4.

A: Morphometric analysis of the Cortex / Medulla (c/m) ratio for evaluation of thymus rejuvenation in three pigs. In two animals, the c/m ratio decreased in the first month after Lupron administration, then all three animals hand increased C/M ratios at 2 months until sacrifice at 6 months, indicating rejuvenation of juvenile thymus architecture in all 3 animals.

B: Percentage of CD4/CD45RA high DP cells in CD4+ T cells in three pigs. One animal (#15630) had a decrease in CD4/CD45RA high DP cells during the course of the experiment. The other two animals had a decrease in the percent of DP cells at 1 month, but rose slightly at the two-month time point where it remained stable until 6 months.

(e) Flow cytometry of thymic derived peripheral naïve CD45high/CD4 double positive T cell populations following Lupron

In order to assess the generation of naïve T cells as a measure of thymopoesis following Lupron injection, we analyzed the percentage of CD4/CD45RAhigh double-positive cells among CD4 T cells in peripheral blood from these 3 animals. This population was 18.3% of the peripheral lymphocytes in #15630, 5.3% in #15959 and 8.6% in #16254 before Lupron injection. In #15630, it decreased to 9.3% at 3-months but then increased back up to 11.7% at 4-months. However, it decreased again to 5.6% at 6-months. On the other hand, in #15959, it decreased to 2.5% at 1-month and then it remained stable at between 2.5 and 3.5% until 6-months after injection. In # 16254, it was 8.6% and decreased to 1.4% at 1-month. However, it increased to 4.8% at 2-months and remained stable at around 5.0% until 6-months after injection (Fig. 4B).

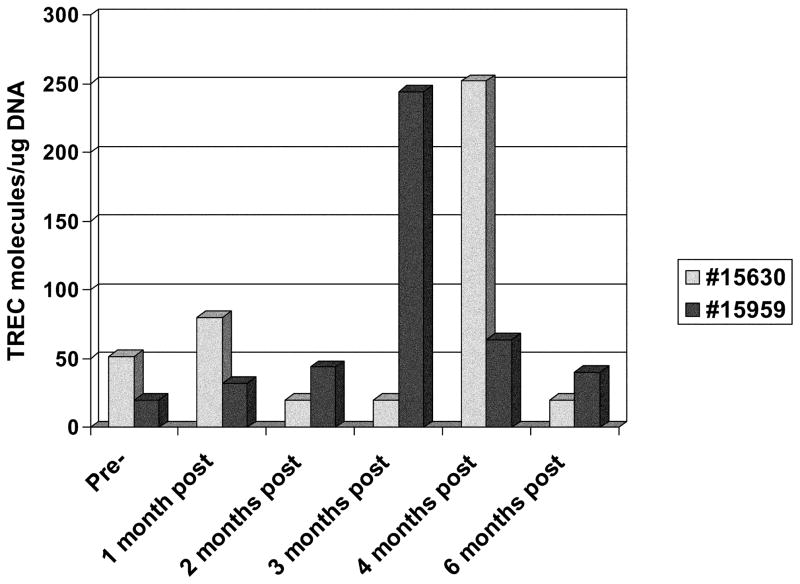

(f) T cell receptor gene rearrangement excision circles (TRECs) for evaluation of thymic emigrant cells after Lupron injection

We also investigated levels of TRECs as a measure of recent thymic emigrant cells among PBLs in two animals (Fig. 5). In #15630, the TRECs increased from 52/ug DNA pre-Lupron to 80/ug DNA one month after Lupron injection, then decreased to 20/ug DNA from the second to the third month. Consistent with the CD4CD45RAhigh FACS data, this animal had a large increase in TRECs to 252/ug DNA by month 4, which then decreased back down to 20/ug DNA by the 6th month following Lupron administration. The second animal, #15959, had a slight increase from 20/ug DNA to 32/ug DNA TRECs 1 month following Lupron injection. Although there was no increase in the CD4CD45RAhigh population by FACS, this animal had a large increase in TRECs to 244/ug DNA by the third month. These high levels did not persist, and TRECs fell to 64/ug DNA by the fourth month following Lupron.

Figure 5.

Levels of TRECs (TREC molecules/ug DNA) in PBMC at Pre and post Lupron injection in animals #15630 and #15959.

Discussion

Data in this study demonstrate that the LHRH agonist is pharmacologically active in MGH miniature swine as demonstrated by the long-term decrease in testosterone levels in mature male pigs. The hormonal alterations induced by Lupron injection resulted in macroscopic and histologic regeneration of the thymus in aged animals by 2 months after depot injection with restoration of juvenile thymic architecture and increased cellularity. However, we were unable to demonstrate that the histologic regeneration resulted in a concurrent increase in peripheral naïve T cells based on our analysis of circulating CD45RA positive T cells. The lack of evidence of recent thymic emigrants in FACS analysis is likely because T cells were not depleted in this study making recent thymic emigrants a small proportion of total T cells and thus difficult to detect in the periphery. The two animals that were evaluated showed increased levels of TRECs in the periphery, suggesting that Lupron did encourage thymopoiesis. However, the elevation in TRECs was transient, with the levels at 6 months following injection approximately the same as pre-injection. Testosterone levels were still low at 6 months after injection when TREC levels returned to baseline, suggesting that LHRH agonist had a direct effect on thymus in addition to any effect resulting from the decrease in levels of sex steroids. Because testosterone levels from female pigs prior to Lupron injection were very low, we excluded females from this study. Further experimental studies would be required to determine whether this strategy might also be appropriate for the female thymus. Strategies for successful thymic rejuvenation have been sought for the treatment of autoimmune disorders, reconstitution of the immune system in HIV/AIDS and post-chemotherapy, and also in the field of transplantation. We have reported that 12-days of high-dose CyA uniformly induces tolerance to MHC class I mismatched kidney allografts in juvenile MGH miniature swine. However, the same regimen fails to induce tolerance if the recipient animal has reached the age of sexual maturity, with the allografts being rejected. Similar findings on the effect of recipient age on transplant outcomes have been reported by Martins et al, specifically that chronic rejection develops in an accelerated manner in elderly recipients, both in rats and in humans. These results suggest that tolerance inducing protocols would be easier to develop for the pediatric population than for adults. Therefore, strategies to rejuvenate an adult thymus might result in extending clinically successful tolerance protocols from the pediatric patient population to adult transplant recipients.

There have been several other studies attempting to characterize the extrinsic factors in the microenvironment that cause thymic involution. Zinc has been implicated as an important factor in thymic involution. Zinc-deficient mice have been shown to have early involution of the thymus compared to age related controls, and studies in mice and humans have shown that zinc supplementation can increase thymulin levels, suggesting a mechanism for thymic regeneration. IL-7 is also known to be involved in the regulation of thymopoiesis. IL7 produced by MHC class II+ thymic epithelial cells has been linked to the survival and proliferation of thymocytes. IL-7 levels decrease with age. However, while thymopoiesis increased in young mice that received IL-7, some groups report that exogenous IL-7 treatment to aged mice did not augment thymopoiesis, while others report an increase in TREC, but no increase in phenotypically naïve T cells. Surgical castration and chemical castration using Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH) have been shown to have a profound rejuvenating effect on the thymus in rodent models and more recently humans. Since in this preclinical large animal model, we aimed to develop a protocol that could be applicable to the adult transplant population, we chose to administer the LHRH agonist, Lupron to our mature swine. Lupron has been used safely and effectively for chemical castration in the treatment of prostate cancer and therefore could be readily used in humans for rejuvenation of the thymus. Indeed recent studies in humans treated with an LHRH agonist show good evidence for increased naïve T cells. While we were able to perform thymic biopsies in this study to confirm a thymic basis for the increase in naïve T cells, due to limitations of the clinical trial, thymic biopsies could not be performed in that study to confirm regeneration of thymic function by LHRH agonist. Non-invasive procedures such as MRI and CT are reliable tools for volumetric assessment of the thymus. Because the body habitus of adult swine was prohibitive, we did not include these radiological assessments in our study. However, because evidence of thymic rejuvenation was observed in this model, we are extending this study to non-human primates and we will include volumetric assessment by MRI in these future studies.

Two of three animals showed marked degeneration of their thymus at 1 month following Lupron injection. When Lupron is used for the clinical treatment of prostate cancer, there is a transient rise in testosterone levels, with peak levels 50% to 100% over basal levels 72 hours after Lupron administration. Lupron is occasionally associated with an acute worsening of bone pain and urinary signs and symptoms during the first week of therapy. The transient rise in testosterone seen in this study could indicate a surge of hormone release that may accelerate thymic involution or thymic emptying as suggested by the small increase in TRECs at one month in 1 of 2 animals. After the first month, as the pituitary became desensitized from the prolonged LHRH signaling, the testosterone levels decreased, and this hormonal state was associated with rejuvenation of the thymus, indicating that testosterone levels may be inversely related to thymus structure and architecture after the administration of Lupron.

Rejuvenation of the thymus with Lupron may augment the patient population that could potentially benefit from tolerance-inducing protocols that are thymic-dependent. In order to determine if the pharmacologically rejuvenated thymus has regained the function, in addition to the architecture, of a juvenile thymus, we plan to examine the ability of aged animals treated with Lupron to accept MHC-mismatched renal allografts with a short-course of immunosuppression that routinely induces tolerance in young animals. We will also determine if thymi of Lupron treated aged animals will support more rapid T cell reconstitution in irradiated recipients of bone marrow transplants after T cell depletion. This work will expand on studies by Boyd et al which suggested that LHRH enhances thymus, bone marrow, and immune system recovery in HSCT patients following myeloablative chemotherapy for malignant leukemia or lymphoma. We also expect that in these T cell depleted animals, assessment of recent thymic emigrants by CD45RAhigh/CD4 double positive cells as a percentage of total T cells will be more accurate.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the following grants/grantors: NIH Program Project 5PO1-A145897 (Project 1) and Norwood Immunology Ltd (Victoria, Australia). We would also like to thank Dr. Takashi Tajiri for his helpful review of this manuscript; and Emma Samelson-Jones for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- ACK

ammonium chloride potassium lysing

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HBSS

Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- LHRH

Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocytes

- TRECs

T cell receptor gene rearrangement excision circles

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Sohn SJ, Thompson J, Winoto A. Apoptosis during negative selection of autoreactive thymocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:510–15. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharabi Y, Sachs DH. Mixed chimerism and permanent specific transplantation tolerance induced by a nonlethal preparative regimen. J Exp Med. 1989;169:493–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachs DH, Sharabi Y, Sykes M. Mixed chimerism and transplantation tolerance. In: Melchers F, et al., editors. Progress in Immunology. VII. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 1171–76. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan A, Tomita Y, Sykes M. Thymic dependence of loss of tolerance in mixed allogeneic bone marrow chimeras after depletion of donor antigen. Peripheral mechanisms do not contribute to maintenance of tolerance. Transplantation. 1996;62:380–87. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199608150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manilay JO, Pearson DA, Sergio JJ, Swenson KG, Sykes M. Intrathymic deletion of alloreactive T cells in mixed bone marrow chimeras prepared with a nonmyeloablative conditioning: Regimen. Transplantation. 1998;66:96–102. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199807150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada K, Gianello PR, Ierino FL, et al. Role of the thymus in transplantation tolerance in miniature swine. I. Requirement of the thymus for rapid and stable induction of tolerance to class I-mismatched renal allografts. J Exp Med. 1997;186:497–506. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada K, Gianello PR, Ierino FL, et al. Role of the thymus in transplantation tolerance in miniature swine: II. Effect of steroids and age on the induction of tolerance to class I mismatched renal allografts. Transplantation. 1999;67:458–67. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199902150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada K, Ierino FL, Gianello PR, Shimizu A, Colvin RB, Sachs DH. Role of the thymus in transplantation tolerance in miniature swine. III. Surgical manipulation of the thymus interferes with stable induction of tolerance to class I-mismatched renal allografts. Transplantation. 1999;67:1112–19. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199904270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada K, Shimizu A, Utsugi R, et al. Thymic transplantation in miniature swine. II. Induction of tolerance by transplantation of composite thymokidneys to thymectomized recipients. J Immunol. 2000;164:3079–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vagefi PA, Ierino FL, Gianello PR, et al. Role of the thymus in transplantation tolerance in miniature Swine: IV. The thymus is required during the induction phase, but not the maintenance phase, of renal allograft tolerance. Transplantation. 2004;77:979–85. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000116416.10799.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamano C, Vagefi PA, Kumagai N, et al. Vascularized thymic lobe transplantation in miniature swine: Thymopoiesis and tolerance induction across fully MHC-mismatched barriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3827–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306666101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nobori S, Samelson-Jones E, Shimizu A, et al. Long-term acceptance of fully allogeneic cardiac grafts by cotransplantation of vascularized thymus in miniature swine. Transplantation. 2006;81:26–35. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000200368.03991.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyan ML. Age-related decrease in mouse T cell progenitors. J Immunol. 1977;118:846–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackall CL, Gress RE. Thymic aging and T-cell regeneration. Immunol Rev. 1997;160:91–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaMattina JC, Kumagai N, Barth RN, et al. Vascularized thymic lobe transplantation in miniature swine: I. Vascularized thymic lobe allografts support thymopoiesis. Transplantation. 2002;73:826–31. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200203150-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nobori S, Shimizu A, Okumi M, et al. Thymic rejuvenation and the induction of tolerance by adult thymic grafts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19081–86. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605159103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachs DH. MHC Homozygous Miniature Swine. In: Swindle MM, Moody DC, Phillips LD, editors. Swine as Models in Biomedical Research. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1992. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.A Public Domain Image Processing Program for the Macintosh by Wayne Rasband and David Bright, published in Microbeam Analysis, 4. 1995.

- 19.Sharifi R, Soloway M. Clinical study of leuprolide depot formulation in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. The Leuprolide Study Group J Urol. 1990;143:68–71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’ Brien A, Hibberd M. Clinical efficacy and safety of a new leuprorelin acetate depot formulation in patients with advanced prostatic cancer. J Int Med Res. 1990;18 (Suppl 1):57–68. doi: 10.1177/03000605900180s109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue JL, Dial GD, Bartsh S, et al. Influence of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist on circulating concentrations of luteinizing hormone and testosterone and tissue concentrations of compounds associated with boar taint. J Anim Sci. 1994;72:1290–98. doi: 10.2527/1994.7251290x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewin SR, Heller G, Zhang L, et al. Direct evidence for new T-cell generation by patients after either T-cell-depleted or unmodified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations. Blood. 2002;100:2235–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuckermann FA, Schnitzlein WM, Thacker E, Sinkora J, Haverson K. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies assigned to the CD45 subgroup of the Third International Swine CD Workshop. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2001;80:165–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(01)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muraro PA, Douek DC, Packer A, et al. Thymic output generates a new and diverse TCR repertoire after autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis patients. J Exp Med. 2005;201:805–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Brink MR, Alpdogan O, Boyd RL. Strategies to enhance T-cell reconstitution in immunocompromised patients. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:856–67. doi: 10.1038/nri1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heitger A, Kern H, Mayerl D, et al. Effective T cell regeneration following high-dose chemotherapy rescued with CD34+ cell enriched peripheral blood progenitor cells in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:347–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosengard BR, Ojikutu CA, Guzzetta PC, et al. Induction of specific tolerance to class I disparate renal allografts in miniature swine with cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1992;54:490–97. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199209000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martins PN, Pratschke J, Pascher A, et al. Age and immune response in organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79:127–32. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000146258.79425.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell WA, Meng I, Nicholson SA, Aspinall R. Thymic output, ageing and zinc. Biogerontology. 2006;7:461–470. doi: 10.1007/s10522-006-9061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraker PJ, King LE. Reprogramming of the immune system during zinc deficiency. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:277–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mocchegiani E, Fabris N. Age-related thymus involution: zinc reverses in vitro the thymulin secretion defect. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17:745–49. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(95)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prasad AS, Meftah S, Abdallah J, et al. Serum thymulin in human zinc deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1202–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI113717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore TA, Freeden-Jeffry U, Murray R, Zlotnik A. Inhibition of gamma delta T cell development and early thymocyte maturation in IL-7 −/− mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:2366–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aspinall R, Andrew D, Pido-Lopez J. Age-associated changes in thymopoiesis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2002;24:87–101. doi: 10.1007/s00281-001-0098-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fry TJ, Mackall CL. Current concepts of thymic aging. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2002;24:7–22. doi: 10.1007/s00281-001-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sempowski GD, Gooding ME, Liao HX, Le PT, Haynes BF. T cell receptor excision circle assessment of thymopoiesis in aging mice. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:841–48. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aspinall R, Henson S, Pido-Lopez J, Ngom PT. Interleukin-7: an interleukin for rejuvenating the immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1019:116–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oner H, Ozan E. Effects of gonadal hormones on thymus gland after bilateral ovariectomy and orchidectomy in rats. Arch Androl. 2002;48:115–26. doi: 10.1080/014850102317267427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azad N, LaPaglia N, Agrawal L, et al. The role of gonadectomy and testosterone replacement on thymic luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone production. J Endocrinol. 1998;158:229–35. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1580229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aspinall R, Andrew D. Thymic atrophy in the mouse is a soluble problem of the thymic environment. Vaccine. 2000;18:1629–37. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00498-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kappler JW, Roehm N, Marrack P. T cell tolerance by clonal elimination in the thymus. Cell. 1987;49:273–80. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutherland JS, Goldberg GL, Hammett MV, et al. Activation of thymic regeneration in mice and humans following androgen blockade. J Immunol. 2005;175:2741–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Utsugi R, Barth RN, Lee RS, et al. Induction of transplantation tolerance with a short course of tacrolimus (FK506): I. Rapid and stable tolerance to two-haplotype fully mhc-mismatched kidney allografts in miniature swine. Transplantation. 2001;71:1368–79. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200105270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldberg GL, Alpdogan O, Muriglan SJ, et al. Enhanced immune reconstitution by sex steroid ablation following allogeneic hemopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Immunol. 2007;178:7473–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]