Abstract

Clinical and biomechanical trials have shown that rigid internal fixation during ankle arthrodesis leads to increased rates of union and is associated with a reduced infection rate, union time, discomfort and earlier mobilisation compared with other methods. We describe our technique of ankle arthrodesis using anterior plating with a narrow dynamic compression plate (DCP). Between 2004 and 2007, 29 patients with a mean age of 24.4 years (range 18–42) had ankle arthrodesis using an anteriorly placed narrow DCP. Twenty-two patients were post-traumatic and seven were paralytic (five after spine fracture and two after common peroneal nerve injury). Follow-up was between 12 and 18 months (average 14 months). A rate of fusion of 100% was achieved at an average of 12.2 weeks. According to the Mazur ankle score, 65.5% had excellent, 20.7% good and 13.8% fair results. Ankle arthrodesis using an anteriorly placed narrow DCP is a good method to achieve ankle fusion in many types of ankle arthropathies.

Introduction

Ankle arthrodesis has become a well-established surgical procedure for severe ankle arthropathy. The rate of union varies according to the surgical technique and the type of patient. While successful results have been reported by many [1, 2], nonunion rates as high as 40% [3] have been described. Numerous complications have been reported including nonunion, delayed union, breakdown of union, pin tract infection, delayed wound healing, skin necrosis and below knee amputation for intractable pain and infection [4–7]. To date more than 30 different methods have been reported with different surgical approaches, articular surface preparation, types of fixation, use of bone graft and postoperative care [8, 9]. Clinical and biomechanical trials have shown that rigid internal fixation leads to increased rates of union and is also associated with a reduced infection rate, a decreased time of union, less discomfort, and earlier mobilisation compared with other methods [9, 10].

This study aimed at assessing the rate, time of union and complications using anterior plating for ankle arthrodesis.

Patients and methods

Between 2004 and early 2007, 29 patients had ankle arthrodesis using anteriorly-placed narrow dynamic compression plates (DCP) (Table 1). Twenty-one were males and eight were females with a mean age of 26 years (range 18–42 years); 18 were right-sided and 11 were left.

Table 1.

Aetiology, time to fusion, complications and final result

| Case number | Age (y) | Gender | Side | Cause | Time to fusion (weeks) | Complications | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | M | R | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 2 | 29 | M | R | Trauma | 12 | - | Excellent |

| 3 | 28 | M | R | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 4 | 36 | F | L | Trauma | 12 | Good | |

| 5 | 42 | F | L | Paralytic | 28 | Midtarsal pain | Fair |

| 6 | 22 | M | R | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 7 | 23 | M | L | Trauma | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 8 | 32 | M | L. | Paralytic | 28 | Midtarsal pain | Fair |

| 9 | 18 | M | L | Paralytic | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 10 | 24 | M | L | Trauma | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 11 | 22 | M | R | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 12 | 25 | M | L | Trauma | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 13 | 30 | M | R | Trauma | 12 | Long talar screw + Midtarsal pain | Fair |

| 14 | 20 | M | R | Paralytic | 12 | Superficial infection | Good |

| 15 | 23 | M | L | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 16 | 25 | M | L | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 17 | 24 | F | R | Trauma | 15 | Long talar screw | Good |

| 18 | 19 | M | R | Trauma | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 19 | 20 | M | R | Trauma | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 20 | 19 | F | L | Paralytic | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 21 | 23 | F | R | Trauma | 15 | Superficial infection | Good |

| 22 | 20 | M | R | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 23 | 20 | M | R | Trauma | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 24 | 27 | F | R | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 25 | 30 | M | L | Paralytic | 28 | Midtarsal pain | Fair |

| 26 | 20 | F | R | Trauma | 12 | Long talar screw | Good |

| 27 | 20 | M | R | Trauma | 10 | - | Excellent |

| 28 | 24 | M | R | Trauma | 8 | - | Excellent |

| 29 | 25 | F | R | Paralytic | 20 | Long talar screw | Good |

M male, F female, R right, L left

Twenty-two were post-traumatic and seven were paralytic (five residual paralysis after spine fracture and two after common peroneal nerve injury). The follow-up period averaged 14 months (range 12–18 months).

Operative technique

Through a midline longitudinal incision in the front of the lower leg and along the talus, the cartilage surfaces of the ankle joint were removed to expose the cancellous layer of subchondral bone including the medial and lateral maleoli. The talus was manually compressed under the tibia and held by a standard AO narrow DCP which was appropriately contoured with two curves (Fig. 1). This is important to allow compression of the talus without causing forward subluxation, and to place the ankle in the required position. The proximal curve is approximately 30° and the distal is 40°. This gives a final bend of 70°.

Fig. 1.

Double bending of the DCP plate

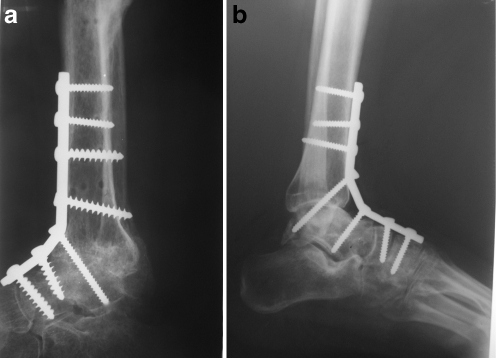

Two screws are placed in the talus and sometimes an additional screw in the navicular bone if more stability is needed. The first screw to be inserted is in the talus, with care to avoid penetrating the subtalar joint. This screw is usually placed through the distal curve of the plate. Then a tibial screw is inserted, which is placed eccentrically to provide compression of the tibio-talar surfaces. A compression screw from the tibia to the talus can be inserted through the proximal curve in the plate; this will greatly improve the compression and stability. The fixation is completed by inserting two more screws through the plate into the tibial shaft (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a X-rays of ankle fusion with anteriorly-placed narrow dynamic compression plate (DCP). b Plate extending to tarsal bones for better fixation

An iliac bone graft can be used. This was necessary in two of our patients with old pilon fractures due to the presence of a defect between the bony surfaces. The position of ankle fusion was neutral flexion, 0–5° of valgus hind foot angulation and 5–10° of external rotation of the foot, as described by Scranton [8]. A below-the-knee plaster cast was applied for two months in osteoporotic bone due to disuse atrophy.

Postoperatively, the sutures were removed after two weeks, and follow up X-rays were done at two and six weeks, then every six weeks until union occurred. Non-weight bearing was advised for two months after which partial weight bearing was allowed until bony fusion occurred.

All patients were evaluated and scored by the Mazur ankle score [11], which gives 50 points for pain, 40 points for function, and ten points for ankle range of motion. Because patients of ankle fusion lack ankle motion the maximum score they could achieve was 90 points. Therefore a score of 80–90 was considered an excellent result, 70–79 a good result, 60–69 a fair result, and below 60 points a poor result.

Results

The average follow-up time was 14 months (range 12–18 months). A rate of fusion of 100% was achieved. The average fusion time was 12.2 weeks (Table 1).

Two patients (6.8%) developed superficial infection at two weeks. In both the inflammation settled with elevation and a short course of antibiotics.

In three patients (10.3%), the radiographs showed that the talar screws had penetrated the subtalar joint resulting in pain. The problem was solved by metal removal shortly after fusion was achieved.

In three patients (10.3%), midfoot pain developed due to the long plates which were hindering movement of the midtarsal joints (Fig. 2b). The long plates were intentionally used to obtain a better fixation through the midtarsal bones in case of insufficient fixation in the talus, due to porotic bones and in paralytic cases. These were removed after complete fusion. One patient (3.4%) developed subtalar and midtarsal pain due to the presence of both complications mentioned above. The plate was removed after achieving union.

According to the Mazur ankle scoring, 19 patients (63.5%) had excellent results, six (20.7%) had good results, and four (13.8%) had fair results.

Discussion

Ankle arthrodesis is still the most common procedure for the management of severe ankle pain from a variety of conditions [8, 12].

The rate of fusion of ankle arthrodesis has varied significantly between different series, some having a rate of nonunion ranging from 35% to 100% [13–15].

Many techniques for ankle fusion have been described, but most can be grouped into anterior bone blocks, trans-fibular and compression arthrodesis [16].

Many compression techniques have been mentioned, starting with Charnely in 1945 [5], who popularised ankle fusion by external compression clamps with nonunion rates ranging from 10% to 38% [17], in addition to the high rate of complications such as pin tract infection, lack of rigid fixation and the cumbersome device.

Other compression techniques included the use of internal fixation which provides a more rigid fixation, allowing shorter periods of postoperative immobilisation and earlier mobilisation of the subtalar and midtarsal joints. This provides flexibility of step and gait [13].

Intramedullary retrograde nailing has also been described as a rigid method for ankle arthrodesis, especially in diabetic cases [18].

Crossed screws have shown good results of 95% union [19], with some biomechanical studies suggesting that three screws are better than two [20].

Wang et al. [21] showed a rate of fusion of 91% with a lateral plate. Dohm et al. [13] had a variable rate of union between 29% using the RAF fibular strut to 100% using the T-plate. Others have achieved rates of 95–97% [14, 15]. Rowan and Davey [22] suggested the use of the anterior T-plate for fixation in cases of ankle fusion with fusion rates of 94%, but they routinely placed the patients in a plaster cast postoperatively, while three patients (9%) had below knee amputation, two (6%) had stress fractures, four (12%) had superficial wound break down, and seven (21%) had subtalar penetration. Wera et al. [23] described the use of a customised 3.5 LCD plate fashioned as an L shape with the transverse limb inserted into the talus through a lateral approach with fusion rates of 100%. Kakarala et al. [24] compared crossed screws to anterior plating plus crossed screws. They have shown better results with the combined technique.

Arthroscopically-assisted techniques [15, 25] have been described to debride the articular surfaces in addition to internal fixation through percutaneous approaches.

In our series the rate of healing was 100% with a relatively lower complication rate. This was achieved by using narrow anterior DCP which allows more rigid fixation along with compression. Certain tips and tricks during insertion of the plate help to improve the results. First, accurate contouring of the plate allows compression of the tibio-talar surfaces in the right position without forward subluxation. Utmost care should be taken whilst inserting the screws in the talus to prevent penetration of the subtalar joint by using X-ray guidance. Also, the plate should not be extended distally to prevent fixation of the midtarsal joints except when more rigid fixation is needed in cases of osteoporotic bones, highly unstable comminuted old fractures or in paralytic feet.

This technique can be used when the subtalar joint is also affected and both ankle and subtalar fusion are needed by extending the talar screws to fix and compress the subtalar joint after excising it through Ollier’s approach [20]. The major advantage of this technique is that it allows early mobilisation of the subtalar and mid tarsal joints.

Care should be taken to put the ankle in the recommended position of fusion, a heel lift may compensate for moderate planter flexion (5–10°) while genu recurvatum will result from a more planter-flexed foot. Also, varus angulation should be avoided, which may be a potent factor in the development of pain and lateral metatarsalgia, while a mild valgus malposition is tolerated better [8, 26]. A limitation of this study is that it has a short follow-up, whereby the tarsal joints may develop arthritic changes due to the stress put on them by ankle arthrodesis on longer term follow-up. Another limitation is that it shows the results of one technique of ankle arthrodesis with no control group, or comparison to other types, but since the final result for this procedure is arthrodesis, then the results may be compared to other studies from the literature.

Thomas et al. [27] reported that in the intermediate term following an arthrodesis for the treatment of end-stage ankle arthritis, pain is reliably relieved and there is good patient satisfaction. However, there are substantial differences between patients and the normal population with regard to hind foot function and gait. Patients should be counselled that an ankle fusion will help to relieve pain and improve overall function. However, it is a salvage procedure that will cause persistent alterations in gait with a potential for deterioration due to the development of ipsilateral hind foot arthritis.

Conclusion

Ankle arthrodesis using an anteriorly placed narrow DCP is a good method to achieve ankle fusion in many types of ankle arthropathies.

The technique described for internal fixation compression arthrodesis provides a high rate of union and satisfactory function. The rigid fixation obtained allows early mobilisation of adjacent hind foot and midfoot joints with earlier return to satisfactory function. The anterior approach is familiar to most surgeons and allows good visualisation, easier correction of the deformity, and proper hardware positioning.

References

- 1.Gschwend N, Steiger U. Stable fixation in hind foot arthrodesis, a valuable procedure in the complex RA foot. Rheumatology. 1987;11:114–125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lionberger DR, Bishop JO, Tullos HS. The modified blair fusion. Foot Ankle. 1982;3:60–62. doi: 10.1177/107110078200300114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C, Tambakis A, Fielding JW. Evaluation of ankle arthrodesis in children. Clin Orthop. 1974;98:233–238. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197401000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallock H. Arthrodesis of the ankle joint for old painful fracture. J Bone Joint Surg. 1945;27:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charnely JC. Compression arthrodesis of the ankle and shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 1951;33B:180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scranton PE, Jr, Fu FH, Brown TD. Ankle arthrodesis: a comparative clinical and biomechanical evaluation. Clin Orthop. 1980;151:234–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrey BF, Wiedeman GP. Complications and long term results of ankle arthrodesis following trauma. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:777–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scranton PE. An overview of ankle arthrodesis. Clin Orthop. 1991;268:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohm MP, Benjamin JB, Harrison J, Szivek JA. A biomechanical evaluation of three forms of internal fixation used in ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:297–300. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moeckel BH, Patterson BM, Inglis AE, Sculco TP. Ankle arthrodesis: a comparison of internal fixation and external fixator. Clin Orthop. 1991;268:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazur JM, Schwartz E, Simon SR. Ankle arthrodesis: long term follow up with gait analysis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:964–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng YM, Huang PJ, Hung SH, Chen TB, Lin SY. The surgical treatment for degenerative disease of the ankle. Int Orthop. 2000;24(1):36–39. doi: 10.1007/s002640050009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dohm MP, Purdy PA, Benjamin JB. Primary union of ankle arthrodesis: review of a single institution/ multiple surgeon experience. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:293–296. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan CD, Henke JA, Baily RW, Kaufer H. Long term results of tibiotalar arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67A:546–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick JM, Morgan CD, Myerson MS, Sampson TG, Mann JA. Ankle arthrodesis using an arthroscopic method: long term follow up of 34 cases. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:428–434. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(96)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglas AD, Mack LC, David AW, Robert PM, Morris HS. Internal fixation compression arthrodesis of the ankle. Clin Orthop. 1990;253:212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagnan RJ. Ankle arthrodesis: problems and pitfalls. Clin Orthop. 1986;202:152–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendicino RW, Catanzariti AR, Saltrick KR, Dombek MF, Tullis BL, Statler TK, Johnson BM. Tibiocalcaneal arthrodesis with retrograde intramedullary nailing. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2004;43(2):82–86. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Huang T, Shih H, et al. Ankle arthrodesis with cross-screw fixation: good results in 36/40 cases followed 3–7 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(5):473–478. doi: 10.3109/17453679608996671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Fitsialos D, Hedman TP. Arthrodesis of the ankle. A comparison of two versus three screw fixation in a crossed configuration. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;304:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang G, Shen W, McLaughlin R, Stamp WG. Transfibular compression arthrodesis of the ankle joint. Clin Orthop. 1993;289:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowan R, Davey KJ. Ankle arthrodesis using an anterior AO T plate of the ankle joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81B:113–116. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B1.8999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wera GD, Snotich JK. Tibiotalar arthrodesis using a custom blade plate. J Trauma. 2007;63(6):1279–1282. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000239254.77569.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kakarala G, Rajan DT. Comparative study of ankle arthrodesis using cross screw fixation versus anterior contoured plate plus cross screw fixation. Acta Orthop Belgica. 2006;72(6):716–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kats J, Kampen A, Waal-Malefijt MC. Improvement in technique for arthroscopic ankle fusion: results in 15 patients. KSSTA. 2002;11(1):46–49. doi: 10.1007/s00167-002-0315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrey BF, Wieddemann GP. Complications and long term results of ankle arthrodesis following trauma. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:777–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas T, Daniels TR, Parker K. Gait analysis and functional outcomes following ankle arthrodesis for isolated ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88A:526–535. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]